Keywords

Heart failure, Metformin, Diabetes, Insulin resistance, Obesity, Randomized trial

Heart Failure is a Common and Deadly Disease

Heart failure affects 1-2% of the adult population in developed countries and the lifetime risk of a heart failure diagnosis is 20% [1]. Patients with heart failure have markedly reduced life expectancy, physical capacity and quality of life. One-year all-cause mortality rates for heart failure patients range between 7 and 17% and the yearly hospitalization rate can be as high as 44% [2]. Morbidity of these patients pose a challenge to the health system due to a high number of contacts. Health care costs are presently higher for heart failure than for any other diagnosis in the American health system [3]. Therefore, in spite of improvement in patient management, there is a definite need for new treatment modalities to improve prognosis, quality of life and health economy for this group of patients.

Insulin Resistance and Diabetes in Patients with Heart Failure

The majority of heart failure patients display wholebody and myocardial metabolic abnormalities [4]. Type 2 diabetes (T2D) and insulin resistance is observed in more than 50% of patients [5,6] and among heart failure patients without diabetes 3%-10% develop new-onset diabetes every year [6,7]. Diabetes and insulin resistance are associated with reduced physical capacity [8] and a 50% increase in yearly mortality [5,6,9,10]. It has been hypothesized that insulin resistance and deranged glucose-, lipid- and protein-metabolism has independent causal effects and promote progression of heart failure and loss of lean body mass [4]. Thus, treatments that counteract these metabolic abnormalities could have beneficial effects [4]. However, at present no major clinical randomized trials have addressed this hypothesis.

Metformin in the Treatment of Diabetes

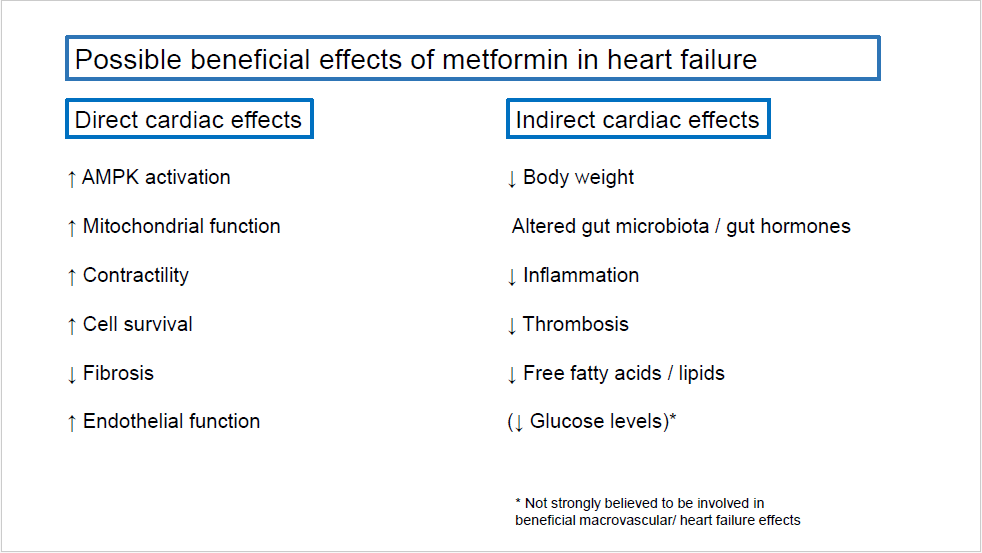

Metformin has been used for decades as a glucoselowering drug. It acts through several mechanisms including reduced hepatic gluconeogenesis and increased insulin sensitivity. In the UKPDS study of patients with T2D, the drug reduced diabetes related death [11] and in patients with insulin resistance, metformin reduced the occurrence of diabetes with 31% [12]. The ORIGIN study showed that reduction in blood glucose levels itself does not reduce cardiovascular event in the population studied [13]. Since the treatment effect of metformin in the UKPDS occurred in spite of similar blood glucose levels, the effects of metformin is believed to be mediated through pleiotropic effects beyond blood glucose control. This could involve both direct and indirect cardiac effects as summarized in Figure 1. Some of the possible direct cardiac effects include AMPK-activation, mitochondrial effects and activation of intracellular cell survival pathways. Whole body effects may also contribute to improved outcome in heart failure patients through weight loss, altered gut hormones, reduced circulating lipids and free fatty acids and suppressed inflammation responses [14-16].

Figure 1. Possible beneficial effects of metformin in heart failure. AMPK: AMP-activated protein kinase

Metformin is Challenged as the Cornerstone in Glucose Lowering Treatment in Type 2 Diabetes

Metformin is used as glucose-lowering treatment in patients with T2D and is taken daily by millions of patients worldwide. As mentioned previously, the UKPDS study of patients with T2D, showed that metformin reduced diabetes-related death with 30%, acute myocardial infarction by 39%, coronary death by 50%, and stroke by 41% over a 10-year period [11]. For that reason, metformin has been the recommended first-line glucose-lowering therapy in the treatment of T2D in Europe for decades and in the USA since the mid90s. However, recent guidelines have downscaled the recommendation for treatment with metformin in T2D [17]. The first reason for this is criticism of the design of the UKPDS trial [18]. It compared conventional therapy with metformin in 753 patients in a study design that was not purely double blind and randomized. Second, few patients in the UKPDS were on randomized therapy after 5 years. Third, there has been no contemporary randomized outcome trials to assess the effect of metformin on cardiovascular events. Finally, and most importantly, the recent large randomized clinical trials of sodium glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT2)-inhibitors [19,20] and glucagon like peptide 1 (GLP1)-analogues [21] have provided strong evidence of a beneficial clinical effect of these newer drug classes in patients with T2D.

Metformin Treatment in Patients with Heart Failur

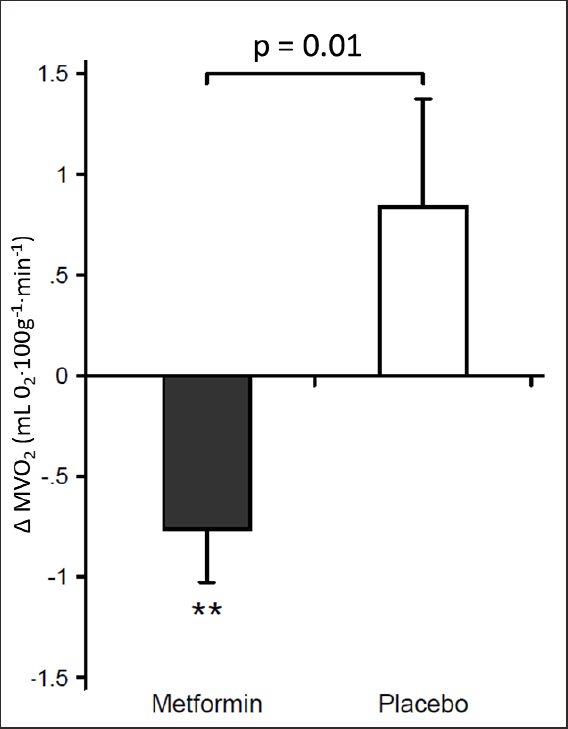

Heart failure patients treated with metformin can develop lactate acidosis and the drug was previously not recommended in these patients. However, during the last decade registry studies reported that Metformin treatment was associated with a 28-35% reduction in mortality [22-24] and that the risk of lactate acidosis was similar in patients treated with and without metformin [25]. For that reason, the ESC, EASD and FDA now approve the use of metformin in heart failure patients. Experimental studies have shown that metformin has pleiotropic cardiac effects beyond the effects on whole body metabolism and insulin resistance and that early treatment with the drug protects against development of heart failure [26,27]. The randomized data on metformin in heart failure patients are scarce. The lack of patent and product protection explain why no private companies will sponsor a large trial with metformin. The largest clinical randomized metformin study in chronic heart failure patients randomized only 60 insulin resistant subjects to treatment for 4 months [28] but failed to reach any firm clinical conclusion due to surrogate endpoints and a short treatment period. The only other randomized study included 36 heart failure patients with prediabetes. In that study, metformin treatment for 3 months reduced myocardial oxygen consumption by 17% as compared with placebo [29] suggesting a beneficial effect on the coupling between energy- and force-generation in the failing heart (Figure 2). This is compatible with a direct mitochondrial effect of metformin [30].

Figure 2. In a double-blind randomized design, 36 non-diabetic heart failure patients received either metformin 1000 mg x 2 or placebo x 2 daily for 3 months. Metformin reduced MVO2 (myocardial oxygen consumption) vs. placebo without changing cardiac work. MVO2 was determined by 11 C-acetate positron emission tomography (adapted from Larsen et al. [29]).

The Metformin in Patients with Chronic Heart Failure and Diabetes or Insulin Resistance Trial (Met-Heft)

The Met-HeFT is a part of the nationwide, randomized DANHEART trial in chronic heart failure patients at 22 heart failure clinics in Denmark. The study design has been described in more detail previously [31]. The Met-HeFT study arm of DANHEART will include 1,100 patients, who will be followed for an average of 4 years. It will be the largest randomized study to date of the efficacy and safety of metformin versus placebo in patients with prediabetes or diabetes and established heart disease. It will also be the first study in heart failure patients powered to address the effect of metformin on clinical outcomes. The main inclusion criteria in Met-HeFT is symptomatic chronic heart failure (New York Heart Association class II-IV), left ventricular ejection fraction ≤ 40% and known type 2 diabetes, insulin resistance or obesity. The target dose is metformin or placebo 1000 mg x 2 daily. In patients with reduced renal function the target dose is reduced. The primary composite endpoint includes death, hospitalization with worsening heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, and stroke. Secondary endpoints include reduction in new-onset diabetes and patient safety (lactic acidosis). Thus, the Met-HeFT study has the potential to yield new knowledge about the causality between insulin resistance, diabetes, abnormal whole body metabolism and the progression of heart failure. As of end of the year 2020, 360 patients have been included.

Conclusion

Registry data suggest a beneficial effect of metformin in heart failure patients. The randomized data on metformin in heart failure patients are scarce although millions of patients take the drug every day. The Met-HeFT study will be the largest randomized study to date of metformin in patients with established heart disease and the first study in heart failure patients powered to address clinical outcomes.

Conflicts of Interest

This investigator driven study is financed through support from various foundations with The Danish Heart Foundation as the main contributor. The Danish Heart Foundation has guaranteed financial support up to an amount of 3.2 million Euro (grant no. 15-R100-A6113-93104). In addition to the direct study costs, the Danish Heart Foundation finances the cost of project managing during the study which is 0.44 million Euro. The DANHEART study has also received funding from the Novo Nordisk Foundation (0.48 million euro, grants no. NNF15OC0017450 and no. NNF18OC0052509), the Danish Health Regions Research Fund (0.33 million euro, grant no. 15/1716), the Independent Research Fund Denmark (0.34 million euro, grant no. DFF 6110-00263) and Aase and Ejnar Danielsens Foundation (0.027 million euro).

Henrik Wiggers has received speaker fees from Merck and Astra Zeneca. He has been principal or sub investigator in clinical trials run by Merck, Pfizer Ltd., Bayer Healthcare AG, Astra Zeneca A/S, Sanofi Aventis, MSD Denmark, Novartis Healthcare A/S, Amgen, Merck Sharp & Dohme Ltd., Bayer A/S, Merck A/S, Novo Nordisk. He has received unrestricted research grants from Novo Nordisk.

Appendix 1

The DANHEART investigators

Henrik Wiggers, Department of Cardiology, Aarhus University

Hospital, Aarhus

Lars Køber, Department of Cardiology, Rigshospitalet,

Copenhagen

Gunnar Gislason, The Danish Heart Foundation

Morten Schou, Department of Cardiology, Herlev Hospital

Mikael Kjær Poulsen, Department of Cardiology, Odense

University Hospital

Søren Vraa, Department of Cardiology, Aalborg University

Hospital

Olav Wendelbo Nielsen, Department of Cardiology, Bispebjerg

Hospital

Niels Eske Bruun, Department of Cardiology, Roskilde Hospital

Helene Nørrelund, Clinical Trial Unit, Aarhus University Hospital

Malene Hollingdal, Department of Cardiology, Viborg Hospital

Anders Barasa, Department of Cardiology, Hvidovre Hospital

Morten Bøttcher, Department of Cardiology, Herning Hospital

Karen Dodt, Department of Cardiology, Horsens Hospital

Vibeke Brogaard Hansen, Department of Cardiology, Lillebaelt

Hospital, Vejle Hospital

Gitte Nielsen, Department of Cardiology, Hjørring Hospital

Anne Sejr Knudsen, Department of Cardiology, Silkeborg

Hospital

Jens Lomholdt, Department of Cardiology, Slagelse Hospital

Kirsten Vilain Mikkelsen, Department of Cardiology, Sydvestjysk

Sygehus, Esbjerg

Bartlomiej Jonczy, Department of Cardiology, Sygehus

Sønderjylland, Abenraa

Jens Brønnum-Schou, Amager Hospital

Monica Petronela Poenaru, Department of Cardiology, Lillebaelt

Hospital, Kolding

Jawdat Abdulla, Department of Medicine, Cardiology section,

Glostrup Hospital

Ilan Raymond, Department of Cardiology, Holbæk Hospital,

Holbæk

Kiomars Mahboubi, Department of Cardiology, Randers

Hospital, Randers

Karen Sillesen, The Pharmacy, Aarhus University Hospital

Kristine Serup-Hansen, Department of Cardiology, Aarhus

University Hospital

Jette Sandberg Madsen, Department of Cardiology, Gentofte

Hospital

Søren Lund Kristensen, Department of Cardiology,

Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen

Anders Hostrup Larsen¸ Department of Cardiology, Aarhus

University Hospital

Hans Erik Bøtker, Department of Cardiology, Aarhus University

Hospital

Christian Torp-Petersen, Department of Cardiology, Hillerød

Hospital

Hans Eiskjær, Department of Cardiology, Aarhus University

Hospital

Jacob Møller, Department of Cardiology, Rigshospitalet,

Copenhagen

Christian Hassager, Department of Cardiology, Rigshospitalet,

Copenhagen

Flemming Hald Steffensen, Department of Cardiology, Lillebaelt

Hospital, Vejle

Bo Martin Bibby, Department of Biostatistics, Aarhus University,

Aarhus

Jens Refsgaard, Department of Cardiology, Viborg Hospital

Dan Eik Høfsten, Department of Cardiology, Rigshospitalet,

Copenhagen

Søren Mellemkjær, Department of Cardiology, Aarhus University

Hospital

Finn Gustafsson, Department of Cardiology, Rigshospitalet,

Copenhagen

References

2. Maggioni AP, Dahlström U, Filippatos G, Chioncel O, Leiro MC, Drozdz J, et al. EURObservational Research Programme: regional differences and 1-year follow-up results of the Heart Failure Pilot Survey (ESC-HF Pilot). European Journal of Heart Failure. 2013 Jul;15(7):808-17.

3. Dunlay SM, Shah ND, Shi Q, Morlan B, VanHouten H, Hall Long K, et al. Lifetime costs of medical care after heart failure diagnosis. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. 2011 Jan;4(1):68-75.

4. Opie LH. The metabolic vicious cycle in heart failure. Lancet (London, England). 2004 Nov 1;364(9447):1733-4.

5. Egstrup M, Schou M, Gustafsson I, Kistorp CN, Hildebrandt PR, Tuxen CD. Oral glucose tolerance testing in an outpatient heart failure clinic reveals a high proportion of undiagnosed diabetic patients with an adverse prognosis. European Journal of Heart Failure. 2011 Mar;13(3):319-26.

6. Kristensen SL, Preiss D, Jhund PS, Squire I, Cardoso, JS, Merkely B, et al. Risk related to pre–diabetes mellitus and diabetes mellitus in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: insights from prospective comparison of ARNI With ACEI to determine impact on global mortality and morbidity in heart failure trial. Circulation: Heart Failure. 2016 Jan;9(1):e002560.

7. Amato L, Paolisso G, Cacciatore FO, Ferrara N, Ferrara P, Canonico S, et al. Congestive heart failure predicts the development of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in the elderly. The Osservatorio Geriatrico Regione Campania Group. Diabetes & Metabolism. 1997 Jun 1;23(3):213-8.

8. Swan JW, Anker SD, Walton C, Godsland IF, Clark AL, Leyva F, et al. Insulin resistance in chronic heart failure: relation to severity and etiology of heart failure. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1997 Aug 1;30(2):527- 32.

9. Gustafsson I, Brendorp B, Seibæk M, Burchardt H, Hildebrandt P, Køber L, et al. DIAMOND Study Group. Influence of diabetes and diabetes-gender interaction on the risk of death in patients hospitalized with congestive heart failure. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2004 Mar 3;43(5):771-7.

10. Doehner W, Rauchhaus M, Ponikowski P, Godsland IF, Von Haehling S, et al. Impaired insulin sensitivity as an independent risk factor for mortality in patients with stable chronic heart failure. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2005 Sep 20;46(6):1019-26.

11. Holman RR, Paul SK, Bethel MA, Matthews DR, Neil HA. 10-year follow-up of intensive glucose control in type 2 diabetes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008 Oct 9;359(15):1577-89.

12. Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, Lachin JM, Walker EA, Nathan DM; Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. New England Journal of Medicine. 2002 Feb 7;346(6):393-403.

13. ORIGIN Trial Investigators: Basal Insulin and Cardiovascular and Other Outcomes in Dysglycemia. New England Journal of Medicine 2012 367;4:319-328.

14. Lexis, C.P., Van der Horst, I.C., Lipsic, E., van der Harst, P., et al. GIPS-III Investigators Metformin in nondiabetic patients presenting with ST elevation myocardial infarction: rationale and design of the glycometabolic intervention as adjunct to primary percutaneous intervention in ST elevation myocardial infarction (GIPS)- III trial. Cardiovasc Drugs Therapy, 26(5), pp.417-426.

15. Nesti L, Natali A. Metformin effects on the heart and the cardiovascular system: a review of experimental and clinical data. Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases. 2017 Aug 1;27(8):657-69.

16. Foretz M, Guigas B, Bertrand L, Pollak M, Viollet B. Metformin: from mechanisms of action to therapies. Cell Metabolism. 2014 Dec 2;20(6):953-66.

17. Cosentino F, Grant PJ, Aboyans V, Bailey CJ, Ceriello A, Delgado V, et al. ESC Guidelines on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases developed in collaboration with the EASD. European Heart Journal. 2020 Jan 7;41(2):255-323.

18. Petrie JR, Rossing PR, Campbell IW. Metformin and cardiorenal outcomes in diabetes: A reappraisal. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism. 2020 Jun;22(6):904-15.

19. Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, et al. Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. New England Journal of Medicine 2015;373:2117-28.

20. McMurray JJ, Solomon SD, Inzucchi SE, Køber L, Kosiborod MN, Martinez FA, et al. Dapagliflozin in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. New England Journal of Medicine. 2019 Nov 21;381(21):1995- 2008.

21. Marso SP, Daniels GH, Brown-Frandsen K, Kristensen P, Mann JF, Nauck MA, et al. Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016 Jul 28;375(4):311-22.

22. Eurich DT, Majumdar SR, McAlister FA, Tsuyuki RT, Johnson JA. Improved clinical outcomes associated with metformin in patients with diabetes and heart failure. Diabetes Care. 2005 Oct 1;28(10):2345-51.

23. MacDonald MR, Eurich DT, Majumdar SR, Lewsey JD, Bhagra S, Jhund PS, et al. Treatment of type 2 diabetes and outcomes in patients with heart failure: a nested case– control study from the UK General Practice Research Database. Diabetes Care. 2010 Jun 1;33(6):1213-8.

24. Andersson C, Olesen JB, Hansen PR, Weeke P, Norgaard ML, Jørgensen CH, et al. Metformin treatment is associated with a low risk of mortality in diabetic patients with heart failure: a retrospective nationwide cohort study. Diabetologia. 2010 Dec 1;53(12):2546-53.

25. Masoudi FA, Inzucchi SE, Wang Y, Havranek EP, Foody JM, Krumholz HM. Thiazolidinediones, metformin, and outcomes in older patients with diabetes and heart failure: an observational study. Circulation. 2005 Feb 8;111(5):583-90.

26. Sasaki H, Asanuma H, Fujita M, Takahama H, Wakeno M, Ito S et al. Metformin prevents progression of heart failure in dogs: role of AMP-activated protein kinase. Circulation. 2009 May 19;119(19):2568-77.

27. Cittadini A, Napoli R, Monti MG, Rea D, Longobardi S, Netti PA, et al. Metformin prevents the development of chronic heart failure in the SHHF rat model. Diabetes. 2012 Apr 1;61(4):944-53.

28. Wong AK, Symon R, AlZadjali MA, Ang DS, Ogston S, Choy A, et al. The effect of metformin on insulin resistance and exercise parameters in patients with heart failure. European Journal of Heart Failure. 2012 Nov;14(11):1303- 10.

29. Larsen AH, Jessen N, Nørrelund H, Tolbod LP, Harms HJ, Feddersen S, et al. A randomised, doubleblind, placebo-controlled trial of metformin on myocardial efficiency in insulin-resistant chronic heart failure patients without diabetes. European Journal of Heart Failure. 2020 Sep;22(9):1628-37.

30. Madiraju AK, Erion DM, Rahimi Y, Zhang XM, Braddock DT, Albright RA, et al. Metformin suppresses gluconeogenesis by inhibiting mitochondrial glycerophosphate dehydrogenase. Nature. 2014 Jun;510(7506):542-6.

31. Wiggers, H., Køber, L., Gislason, G., Schou, M., Poulsen, M.K., et al. The DANish randomized, doubleblind, placebo controlled trial in patients with chronic HEART failure (DANHEART): A 2× 2 factorial trial of hydralazine-isosorbide dinitrate in patients with chronic heart failure (H-HeFT) and metformin in patients with chronic heart failure and diabetes or prediabetes (Met- HeFT). American Heart Journal.