Abstract

Background: In South Africa, new amended regulations required a review of complementary and alternative medicine (CAMs) call-up for registration from November 2013. This impacted traditional healers (THs)’ compliance with the regulatory authorities’ on the good manufacturing practice which in return affected the public’s access to CAMs. This investigation embraces methods, THs use to diagnose and treat diabetes (DM) in Mamelodi. Furthermore, it assesses what their purported medications comprise of. It is fundamental to understand the functioning of the South African Health Products Regulatory Agency (SAHPRA). Regulations surrounding registration and post-marketing control of CAMs are crucial, needing a solution.

Method: The study comprised of dedicated questionnaires, distributed amongst THs to gain knowledge on their diagnosis and identify the CAMs used. It also included non-structured surveys on pharmacies to identify and assess compliance of those CAMs with the SAHPRA (previously Medicines Control Council (MCC)) regulations.

Result: TH’s do not use any medical tests or materials for diagnosis. They use skeletal bones and prayers. Most CAMs found in the pharmacies have a disclaimer on the label when not evaluated by MCC/SAHPRA. Only two medicines were registered: ‘Manna blood sugar support and super moringa’. Self-provided TH treatment list for DM displays 20 different active ingredients in various CAM therapies. The most common treatment used is a plant and herbal-based (Muti) such as 1-ounce (Oz) mixture.

Conclusion: Diagnosis of diabetes by THs is mostly done by divination. TH’s have an understanding with regards to drug safety, are aware of regulations but do not comply with SAHPRA. Their purported medication seems to be successful, according to themselves but further investigation and proper collaboration between the THs and bodies is in demand. Future study is needed by a competent researcher with traditional medicine qualifications.

Keywords

Traditional healers, Diabetes Mellitus, South African Health Products Regulatory Agency, Medicines Control Council, Complementary and alternative medicines.

Introduction

CAM is widely used by patients to treat and prevent certain diseases, providing emotional and physical support [1]. The National Centre for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) defines CAM as a "group of diverse medical and health care systems, practices, and products that are not presently considered to be part of conventional medicine" [2]. In the past 20 years, the increase in availability and ease of access to allopathic, conventional, or Western medicine through public health and private medical practices, led to an increased quality of life. Despite this tendency, numerous factors led to the widespread and increased appeal of CAM globally; over 80% of individuals in developing nations use CAM. One-third of the global population, with 50% in the impoverished parts of Asia and Africa do not have regular access to essential drugs [3,4]. CAM and Traditional Medicine (TM) vary widely between countries. The World Health Organisation (WHO) published and summarised numerous surveys on their uses [5,6]. Using CAM and TM is prevalent amongst patients, suffering from chronic, painful, debilitating or terminal conditions. The use in conditions, such as in human immunodeficiency virus infection and acquired immune deficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) and cancer is far higher than other conditions, ranging from 50% to 90% of cases [6,7]. Numerous CAM practices are not scientifically validated by medical authorities and are inadequately accepted. These practices include, Homoeopathic medicine, Western herbals, traditional Chinese medicine, Ayurvedic medicine, Unani tibb and aroma therapeutic medicine [8-10].

Safety aspect of complementary and alternative medicines

The effects caused by the biodiversity of CAM and TM, indicate a major concern [3,5]. Over-harvesting of endangered species and the possible extinction of medicinal plants is a concern, not only in South Africa, but globally. Concerns remain for government authorities. These concerns include, poaching of American ginseng and black rhinoceros horn [5]. Another issue that should be reviewed, is the quality and control of materials used by THs. The control of ingredients and manufacturing procedures do not always meet the standards and requirements for their intended use. Manufacturing should be done according to Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) [5]. Complications resulting in the incorrect use of traditional therapies, also indicate a pressing issue. The herb, Ma Huang (Ephedra), is traditionally used in China to treat short-term respiratory congestion. In the United States, the herb served as a dietary aid; long-term use led to several deaths, heart attacks and strokes [11]. In another instance in Belgium, the incorrect use of CAM, resulted in (at least) 70 patients requiring renal transplants or dialysis for interstitial fibrosis of the kidney, after consuming the wrong herb from the Aristolochiaceae family as a dietary aid [7,11].

Regulations of complementary and alternatives medicine

Regulation and control of medicine is not an option but an imperative for national health programmes. CAM regulations should assist in minimising the risks of unproven medical claims with the misuse of certain traditional therapies. In South Africa, the regulations surrounding CAM and TM, significantly progressed into the legislative framework for health practitioners. Amendments to the Medicine and Related Substances Act, 1965 (Act No. 101 of 1965), as outlined by the DoH and former Medicine Control Council (MCC), set new boundaries for CAM marketing and sales in South Africa [12].

The legislation, published into law on 15 November 2013, calls for certain standards to be met, using a phased-in approach for implementation. These standards, amongst others, include changes to label information on packages (by 15 February 2014) and registration of certain product groups with the former MCC (several dates and call-ups) [12]. These standards relate to products falling within the CAM definition, as outlined by the DoH and former MCC [13,14]. Thousands of products are available in South Africa; these can be categorised as complementary medicine [12]. The legislative requirements for these practices of medicine fall within the definition of complementary medicine and should comply with the published legislation of 2013 and 2017 [14-16]. The CAM legislation also indicate an on-pack labelling requirement, differing from previous standards. Thus, the medication container should include the following: A disclaimer on the label (until it is evaluated) to the effect of: “This medicine has not been evaluated by the SAHPRA. This medicine is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any disease”. Label information must also be supplied in a second language [16].

Brands and manufacturers should note the proof of their products’ medical claims, divided into low-risk and a high-risk claim [16,17]. The former MCC did not hold the statutory power to enforce the Medicine Act or the ‘call-up for registration’ of all CAMs. The authority resided only with the DoH [13], however it was replaced by a new regulatory authority in 2016, entitled, the South African Health Products Regulatory Authority (SAHPRA), representing an upgraded version of the MCC who now has the power to enforce the Medicines Act as envisaged. It is described as similar in model to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The 2008 amendment also provided SAHPRA with the final authority to approve new products, medical devices or in vitro diagnostics (IVDs), requiring the approval of the Minister of Health, resulting in significant time delays [17].

Powers and functions of the South African Health Products Regulatory Authority (SAHPRA)

SAHPRA provides the monitoring, evaluation, regulation, investigation, inspection, registration and control of medicine, scheduled substances, clinical trials and medical devices, IVDs and related matters in the public’s interest [2,18]. Concerning licencing, SAHPRA holds the authority to grant and renew licences to manufacture or act as a wholesaler or distributor of any medicine, scheduled substance, medical device or an IVD. SAHPRA holds a broad mandate in the public interest [16,18]. According to Dr. Joey Gouws [14], the registrar of the former MCC, in the legislative update and status of SAHPRA, guidance to meet regulators’ expectations and regulations to control CAM, should occur from 2014 to 2019 [12,14]. SAHPRA should implement the updated and extended legal regimes, regulating all medicine, medical devices, IVDs, complementary medicine, cosmetics, and foodstuffs.

SAHPRA new regulations

Further, SAHPRA’s mandate has expanded to include the regulation and control of radiation, emitting devices, and radioactive nucleotides into the scope of authorities appearing in the Medicines Act and Hazardous Substances Act, 1973(Act No. 15 of 1973). Another regulation (40) on implementation of good vigilance practice standards and quality management system for vigilance activities; the regulation of biological products biosimilars, and medical devices ad hoc inspections to comply with the South African National Accreditation System (SANAS) and other conformity assessment body with standards i.e. ISO13485 [10,18].

- Implementation of regulatory draft framework for complementary medicines

What are Complementary medicines?

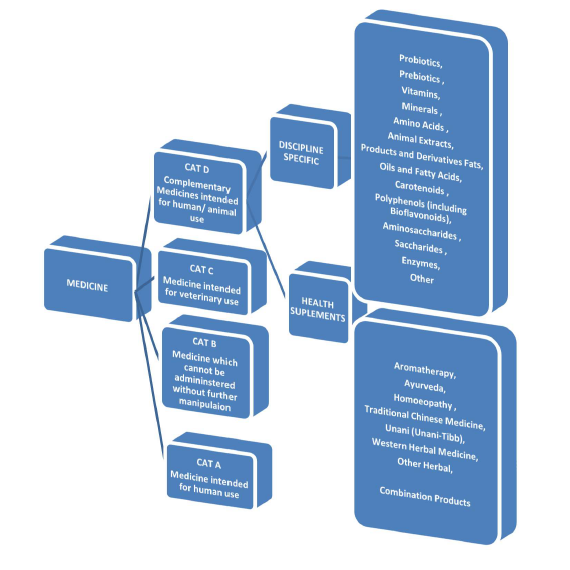

According to the SAHPRA, complementary medicines (CMs) are non- indigenous disciplines. They refer to a broad set of health care practices that are not part of that country’s own tradition and are not integrated into the dominant health care system [12]. SAHPRA general regulations regarding the Medicines Act published on August 2017 is to allow an amendment to the CMs definition identifying ‘health supplements’ as an additional group of products falling within ‘CMs definition’, see Figure 1 below. These products will be reviewed over time and regulatory oversight regarding these types of medicines will be established. According to the roadmap, all CMs must be submitted by 15 May 2019 [10,12]. There is a need to strengthen the understanding and culture regarding regulation within the CM industry, since it is a previously unregulated industry.

- Implementation of regulation draft framework regarding African traditional medicines

Traditional medicine or African traditional medicines (TM) is the sum or total of the knowledge, skills, and practices based on the theories, beliefs, and experiences indigenous to different cultures, whether explicable or not, used in the maintenance of health as well as in the prevention, diagnosis, improvement or treatment of physical and mental illness [10]. SAHPRA also organised a working group to investigate regulation concerning African traditional medicines (ATMs) product for bulk sale (i.e. not ATMs combined by an individual healer prescribed for a specific patient). This followed recommendations for CMs committee to council provision for regulations of ATMs. Draft level framework is still ongoing and includes dialogue with the African National Healer’s association [10].

Health supplements or vitamins: The categorization of medicines of SAHPRA, displays health supplements under category D. They are any substance, extract or mixture of substances as determined by the authority, sold in dosage forms or purported for use in restoring, correcting or modifying any physical or mental state by complementary health, supplementing the diet or nutritional effect. These exclude injectable preparations, medications or substances as schedule 1 or higher in the Act [10]. Vitamins fall under the ‘discipline specific’ subcategory of Category D CMs. They are organic molecules that are essential nutrients and cannot be synthetized in the organism. Therefore, vitamins must be obtained through a diet [10,18,19].

Traditional healers and training: In South Africa, THs are known as, amongst others, inyangas (herbalist), Isangomas (diviners), and witch-doctors, forming a crucial part in providing health care to most South Africans [5]. Isangomas are spiritual healers with the majority being women. The way they connect with the ancestors is to throw the bones. i.e each bone has a meaning, representing a patient’s life. Inyangas means trees in Zulu, are healers that make medicine from herbs, roots and bark. Ground up rocks, animal horns and bones can also be used to make their medicines. After patients are diagnosed, inyangas go to the bushes to find specific plants necessary for healing (herbs and roots called Muti). These medications can be bought in markets as well as directly from inyangas [5,20-23]. THs believe that they are called by ancestors. Regulating THs is under the auspices of the Health Service Professions Act of 1982, as amended. Qualified THs are registered with the Traditional Healers’ Organisation (THO) and are provided with a certificate of competence. They are recognised as South Africa health practitioners under the Traditional Health Practitioners Act of 2007. An inconvenient situation found in countries, such as South Africa, is the uncertainty that THs hold a degree, diploma, or certificate, demonstrating sufficient proficiency in traditional healing as the knowledge they gained, was passed from generation to generation [24]. The THO ensures that all its members endorse human rights principles and frameworks in their dealings within the profession [25].

Diabetes Mellitus and Complementary and Alternative Medicine: DM is a chronic disease affecting glucose metabolism. It is associated with abnormal elevated levels of glucose in the blood. Normally, the pancreas produces insulin and it is responsible for lowering the blood glucose concentration [26,27]. Insulin resistance play a major pathophysiological role in type 2 diabetes and it is highly associated with major health problems including obesity, hypertension, coronary artery diseases, dyslipidaemias and cluster of metabolic and cardiovascular abnormalities defining the metabolic syndrome [28]. Three types of diabetes are differentiated: Type 1, Type 2 and gestational diabetes [27]. Patients with Type 1 diabetes produce little or no insulin and are referred to as insulin-dependent. Patients with Type 2 diabetes do not respond normally to insulin due to insulin resistance and are referred to as non-insulin-dependent diabetes. Approximately 90% to 95% of patients with diabetes are diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes whereas only 5% are diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes. Gestational diabetes affects only pregnant women and usually disappears after they give birth [27,29,30]. Physicians would use the following laboratory tests to aid in diagnosing diabetes mellitus [27-31]:

Random glucose test: Blood glucose levels determined from a non-fasting subject; a glucose level of 200 mg/dl (11.1 mmol/l) or higher will suggest diabetes.

Fasting blood sugar (FBS): Blood glucose levels determined after 8 hours of fasting; a fasting blood glucose level from 70 to 100 mg/dL (3.9 to 5.5 mmol/l) is considered normal. 100 to 125 mg/dL (5.6 to 6,9 mmol/L) is considered as prediabetes.

Glucose tolerance test (GTT): Measures the body response to a glucose challenge. The patient is asked to fast for 10-12 hours and then receives a 75 g glucose containing drink and plasma glucose levels measured base-line, time 0, time 2 hours post glucose drink and so on. For 1-hour GTT, glucose level below 180 mg/ dL (10 mmol/l) is considered normal; for 2 hours, glucose level below 140 mg/ dL (7.8 mmol/l) is normal and between 140 mg/ dL and 200 mg/ dL (11.1mmol/l) indicate impaired glucose tolerance. Above 200 mg/ dL at 2 hours confirm a diagnosis of diabetes.

Postprandial glucose test: Blood glucose levels determined 2 hours after eating. Glucose level under 140 mg/ dL (7.8 mmol/l) and pre-prandial plasma glucose between 90-130mg/dL (5-7.2mmol/l) is normal. Higher values indicate diabetes.

Glycated haemoglobin (HbA1C) is another test that assists in assessing the patients long-term (3 months) glycaemic control.

Measurement of insulin sensitivity/resistance: It is essential to test and validate its reliability before Insulin resistance can be used as an investigation in patients. The ‘hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp’ and the ‘intravenous glucose tolerance test’ are currently used as a referencing standard. Some simple methods from which indices can be derived have been validated. These include homeostasis model assessment (HOMA), and quantitative sensitivity check index (QUICKI). For clinical uses, HOMA-insulin resistance, QUICKI and Matsuda are suitable while HES, Belfiore, Cederholm, Avignon and Stumvoll indexes are suitable for research purposes [28].

Complementary medicines for diabetes mellitus: Plant/herbs and dietary supplements are globally some of the most used CAM therapies for diabetes patients [19]. Researchers studied different CAMs, used by patients to treat diabetes. Although some of these therapies are found to be effective in patients, some have not, and may even be dangerous. Researchers need to evaluate GMP of these therapies [30]. This would assist patients to manage diabetes or lower the risk of developing DM [31].

Plant based vs herbal medicines: Plants are a general group of living organisms belonging to the plant kingdom that lack the power of movement and can produce its own food. The lifespan depends on the group of plant but can grow both on earth and water. They are divided into two major groups based on reproductive (flowering and non-flowering plants) [32,33]. An herb is a type of soft plant with no little or no linin. It has herbaceous habits (herb, shrub, tree, climber and liana) that can have a much shorter lifespan [33,34]. Medicinal plants can be considered as herbal plants but not all herbal plants can be considered medicinal plants.

Materials and Methods

The study was quantitative, exploring descriptive study design, based on investigating CAM therapies amongst diabetic patients in Mamelodi area of a township northeast of Pretoria, Gauteng South Africa with first language being Sotho and Zulu [35]. The informed consent was elaborated on, explaining the questionnaires, distributed amongst THs available in English, Zulu and Northern Sotho/Sepedi. It was administered and supervised with the guidance of THs and other volunteers, skilled in these languages. Selected pharmacies were visited to discern whether they stock CAMs, and then proceeded in identifying those used to treat DM. The research targeted 10 sites. This investigation aimed to identify the type of assessment tools used by THs to DM. Their knowledge on CAMs safety, quality, control and pharmacovigilance, was also investigated to determining their compliance with the new SAHPRA regulations. The estimated time line for the project was 1 month.

Questionnaires validation was compromised because of non-random or convenient sample (THs that happened to come during the workshops were not all the THs from Mamelodi, no census or list of Mamelodi THs). The nonvalidated questionnaires scale was measured to check internal consistency on the nature and purpose of the study.

Results

Traditional healer demographic data

According to the 75 TH’s, 60% (45) were females and 40% (30) were males (Figure 2). The female was found to have influence of practise in traditional medicine. It is known that both men and women can become THs in South Africa [23]. 64 (85%) of the traditional healers were from the black population, 2 (3%) were whites, 7 (9%) coloured.

Traditional healers’ qualifications

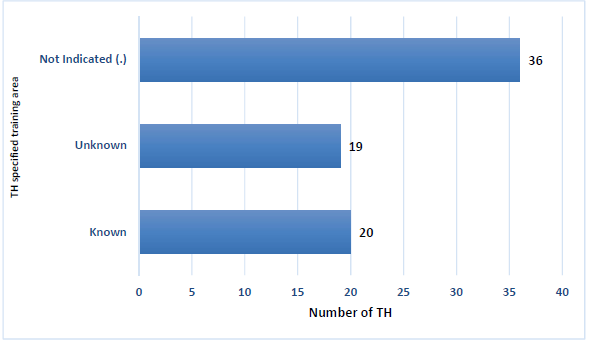

Only 2 (3%) THs were holding a degree; there were 5 (7%), THs with a certificate, 10 (13%) THs holding a post matric qualification and 43 (57%) of THs had no matric. Lastly 12 (16%) THs had matric certificate, 19 (25%) THs did not mention the specific institution or area, 20 (27%) THs specified the training course area (Figure 2). The remaining 36 (45) THs again did not indicate any response.

Figure 2. TH specified training area*.

*Area: Training courses were attended in various parts of Pretoria and Limpopo, such as Mamelodi Extension 5, Pelindaba, Atteridgeville, Giyani, Hammanskraal and Bela-Bela

There were only 4 THs who were holding a ‘Gauteng traditional and faith medical practitioner’s certificate’

To become a TH diviner or herbalist, a minimum standard for training student is 12 months. To qualify for registration for certificate the applicant needs to be minimum 18 years of age [24]. The trend is recognized that THs bodies are trying to formalize THs training and congruency bringing it in-line with the SAHPRA philosophy of formalizing this profession and its recognition. Recently, 39 THs in Mamelodi were granted licences to heal by the THO [36].

Traditional healer’s experience

An important aspect was the experience healers had attained. There were 6 (8%) THs who had indicated over 15 years of practice; 11 (15%) THs indicated 11-15 years of practice; 17 (23%) THs indicated 0-2 years of practice; 18 (24%) THs indicated 3-5 years of practice; 23 (31%), THs indicated 6-10 years of practice. The more years you spend in the practice, the more experience you gain as a trainee. A trainee trains formally under another TH who acts as a tutor for a period of a few months to years [21,24].

Traditional healer’s source of Complementary and Alternative Medicine

Traditional healer’s self-prepared medication is known as Muti. 48(64%) indicated preparing their own Muti. Among them all: 9 (16%) THs sourced their CAMS both locally and abroad. 44 (76%) which is the majority of the THs reported sourcing their CAMS from the bushes or local pharmacies.

Percentage of Traditional healers who had patient with Diabetes mellitus

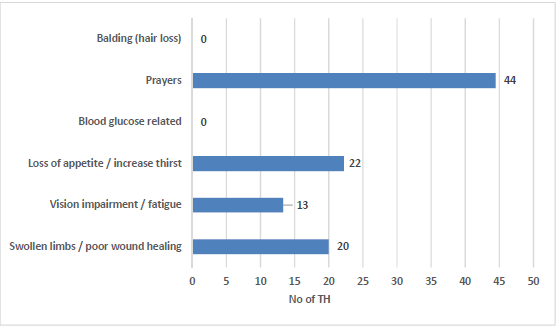

As it is known, poorly controlled diabetes gets challenged with chronic complications [37]. 2 (3%) of the THs had indicated to have 7-8 patients with DM per month, 3 (4%) THs indicated to have 5-6 patients and 8 (11%) THs indicated to have 3-4 patients. A group of 21 (28%) THs indicated to have 1-2 patients. 11 (15%) THs, indicating to treat type 1 diabetes; 61 (81%) THs being the majority number, indicated treating type 2 diabetes. None of the THs used a blood glucose related examination for diagnosis of DM. In addition, no diagnostic criteria such as balding (hair loss) was recorded. The assessment and type of tools used is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3. THs diagnostic and assessment methods.

Regarding the assessment tools, 18 (22%) were making use of skeletal bones and shells; 20 (24%) were making use of physician’s clinical notes brought by their patients; 22 (27%) were making use of prayers for diagnosis of DM; 23 (28%) said to use no assessment tools for treatment of DM.

As THs are known to “go beyond just treating the disease”, primarily, they ‘connect’ collectively and individually this lead or guide to them to the healing practise [37,38].

Details of purported treatment (Complementary and Alternative Medicine) used by traditional healers

The most common herbal active ingredients used today in treating DM are flavonoids, tannins, phenolic, and alkaloids [37-39]. With regards to medication prescribed for type 1 diabetes, 5 (14%) THs used herbs as treatment for type 1 diabetes; 6 (17%) THs used root of barks as treatment for type 1 diabetes; 11 (31%) didn’t mention; 13 (37%) THs being the majority number used plants. With regards to type 2 diabetes: 9 (10%) used herbs; 18 (20%) used roots; 27 (30%) used other treatment recipe not mentioned; 36 (40%) being the majority of again used plants as purported treatment. There were 20 treatments for DM identified in the Mamelodi area mostly for type 2 DM. The ringleader of THs in the Mamelodi and an ethnobotanist from the University of Johannesburg assisted in identifying botanical names of the plant products. Among the list illustrated as in table 1 below, 13 traditional healers recorded using mostly vitamins and minerals in combination with other compounds such as 1 ounce (Oz) mixture (composed of Oz First flush, Oz lily herbs, Oz flower of Ypres, OZ mulch root and OZ Makasan). The THs indicated that their remedy had a better effect on patients when combined. The “Elder” THs made use of plants, trees and bark roots well-known for their natural antioxidants and effective herbal medicines: The plants leaf extracts are simmered; the patients then drink the extract liquid, believing that the bitter taste of the leaves helps to clean the blood (reduce high glucose concentrations in the patient’s bloodstream.) [40]. In discerning the most prevalent prescribed CAMs, it was found that certain traditional healers chose more than 1 answer as an option for their mostly prescribed DM treatment, e.g. plants / herbal based + vitamins.

Traditional healers’ treatment feedback obtained from patients

After the treatment, 2 (3%) THs did not share response regarding their patient’s feedback; 16 (31%) THs mentioned that they did not receive any patient feedback. Lastly, 57 (76%) THscomprising the majority number mentioned that they received feedback.

Treatment efficacy assessment by traditional healers

Another important aspect was the treatment efficacy of TH. In total, 62 traditional healers who answered this question, 58 assessed the efficacy of their DM treatment 4 (6%) THs did not assess the efficacy of DM treatment. 7 (11%) assessed the DM treatment efficacy based on an increased referral of their new patients; 12 (19%) assessed the DM treatment efficacy via special referrals (interesting, this was seen as a sign of successful treatment). 39 (63%) assessed the efficacy based on their patient feedback.

Complementary and alternative medicine regulations analysis

As SAHPRA, took control of the purpose of the MCC in 2016 to implement the updated and extended regime [40]; 16 (21%) said to have registered their CAMS with the SAHPRA. The majority, 59 (79%) reported not registering their CAMS with the SAHPRA (reasons for not registering are depicted in Figure 4); 3 (4%) THs, did not respond to the question on whether they were aware of the new regulations. 31 (41%) said they are not aware of the SAHPRA regulation of CAMS; 41 (55%) comprising the majority indicated to be aware of the SAHPRA regulation. 33 (44%) traditional healers did not comply with the SAHPRA regarding new regulation for CAMS; 42 (56%) traditional healers indicated compliance with the SAHPRA new regulation regarding CAMS. In the questionnaires, the 41 (55%) number who said not to be aware of the regulation indicated their compliance to the SAHPRA new regulation of CAMs (hence being ironic). As DM is a chronic illness and the number of patients is on the rise, there should be allopathic medicines with more facilities available [41,42].

List of Complementary and Alternative Medicine found over-the-counter

Herbal medicine is sold in pharmacies as non-scheduled Over-the-counter (OTC) medicine also by licensed practitioners, without restriction. There were 13 vitamins and supplements as referenced by the THs available at pharmacies in the vicinity (Table 2). Most of the CAMs manufacturers knew about the SAHPRA legislation of 2013. One OTC CAMs recorded registered by the SAHPRA was known as ‘Manna blood sugar support’. Another OTC CAMs that appears to show an inclination towards SAHPRA regulations is Insumax used as a multivitamin in conditions that are linked to or exacerbated by insulin resistance. The CAMs found on the pharmacy shelves, were mostly vitamins and minerals, along with some powder extracted from the Moringa tree (also SAHPRA registered), cinnamon powder and chromium. The rest of vitamins and supplements had the former disclaimer “This medicine has not been evaluated by the Medicine Control Council. This medicine is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any disease” [40-43].

Conclusion

In this research, most THs did not have materials to diagnose diabetes DM. They used skeletal bones with shell parts and practiced spiritual beliefs [38]. The way THs diagnosed diabetes and the materials that they used differed from Western medical doctors. This is problematic to the DoH and SAHPRA. Failure to follow regulations can cause harm to their patients. This is a reason indicated by the South African DoH as to why challenges are still being faced concerning regulating CAM. THs again refuse to comply with new regulation because they reported that, when compared to medical doctors’ practices, they differ throughout, although their intensions are the same. The outcomes are different when treating the patient. According to Laura Eggertson “TM is a system of medicine in the same way that Western medicine is a system; the same way naturopathic medicine is a system” [44]. Only 2 OTC CAMs registered with the SAHPRA. 44% of THs do not want to comply; they want to be self-regulated [45]. For good pharmacovigilance and avoiding toxicity, they need to improve safety, efficacy and quality of TMs. This would in-turn lead to an increase in development of TM. This is crucial, as THs have more influence and are more accessible than Western medical doctors.

The cooperation of medical doctors and THs can assist in decreasing the conflicts and misunderstandings amongst the two different paradigms of medical fields [46].

Acknowledgements

This project could not have been completed without the assistance of the following individuals and organizations. ANBG (l’agence de nationale des bourses du Gabon) and the NRF (National research foundation) for their financial support; the University of Pretoria Department of Pharmacology regarding Regulatory Pharmacology, with special thanks to my supervisor Dr. G.L Muntingh for all his support and guidance throughout my research as well as traditional healer Maria from Mamelodi, and Mrs. L. Marx and J. Marais for assistance with editing. I am indebted Dr G.L Muntingh and my family for their support.

References

2. US. Department of Health and Human Services. National Institutes of Health, What Is Complementary and Alternative Medicine. NCCIH.

3. World Health Organisation. Legal Status of Traditional Medicine and Complementary/Alternative Medicine: A Worldwide Review. WHO.

4. https://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/release38/en/

5. Debas H, Laxminarayan R, Straus E. complementary and alternative medicine. In: Jamison D et al., editors. Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries. (2nd edn.) Washington (DC): The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank; 2006. Chapter 69

6. https://www.who.int/medicines/publications/traditional/trm_strategy14_23/en/

7. Medagama AB, Bandara R. The use of complementary and alternative medicines (CAMs) in the treatment of diabetes mellitus: is continued use safe and effective?. Nutrition journal. 2014 Dec; 13(1):102.

8. Birdee GS, Yeh G. Complementary and alternative medicine therapies for diabetes: a clinical review. Clinical Diabetes. 2010 Oct 2; 28(4):147-55.

9. https://nccih.nih.gov/health/integrative-health

10. Gower N, complementary mediines (CMs) in the new dispensation. Respice adspice prospice, SAAPI 2017; Industry in Transition; Midrand, South Africa.

11. Heller T. Perspectives on Complementary and Alternative Medicine. in: Lee-Treweek G, Katz L, Stone J, Spur S., editors. can Complementary and Alternative Medicine be classified. 1st ed. Routledge; 2005. Chapter 2.

12. Naidoo S, Greyling , Babamia N, South African Health Products Regulatory Authority (SAHPRA), strategic plan for the fiscal years 2018/19-2022/23. 2018.

13. http://www.mccza.com/Publications/Index/1

14. http://www.sapraa.org.za/presentations/March2015/Legislation%20update%20and%20status%20of%20 MCC%20SAHPRA20-%20Dr%t20Joey%20Gouws.pdf

15. Doms R. AMS regulations comment/specific notes.

16. PSSA Perspectives. Roadmap for the registration of complementary medicine, Pharmaceutical Society of South Africa. S Afr Pharm J. 2014; 81(1).

17. http://www.fastmoving.co.za/activities/complementary-and-alternative-medicine-cams-know-thebasics-4702

18. http://www. l exology.com/library/det a i l .aspx?g=b47d21e3-0d2e-4137-b298-538f4b027ee7

19. Manson JE, Bassuk SS. Vitamin and mineral supplements: what clinicians need to know. Jama. 2018 Mar 6; 319(9):859-60.

20. South African Department of Health. Traditional health practitioner regulation 2015. In: government gazette no.37600, Notice 1052, Pretoria: government priming works. 2014.

21. Truter I. African traditional healers: Cultural and religious beliefs intertwined in a holistic way. South African Pharmaceutical Journal. 2007; 74(8):56-60.

22. De Roubaix M. The decolonialisation of medicine in South Africa: Threat or opportunity?. SAMJ: South African Medical Journal. 2016 Feb; 106(2):159-61.

23. http://www.traditionalhealth.org.za/t/traditional_healing_and_law.html

24. Street RA. Unpacking the new proposed regulations for South African traditional health practitioners. SAMJ:South African Medical Journal. 2016 Apr; 106(4):325-6.

25. https://m.news24.com/SouthAfrica/news/sahealth-sector-faces-a-crisis-20161008

26. Yeh GY, Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Phillips RS. Use of complementary and alternative medicine among persons with diabetes mellitus: results of a national survey. American Journal of Public Health. 2002 Oct; 92(10):1648-52.

27. http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/home/index.html

28. Gutch M, Kumar S, Razi SM, Gupta KK, Gupta A. Assessment of insulin sensitivity/resistance. Indian journal of endocrinology and metabolism. 2015 Jan; 19(1):160.

29. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes -2015. Diabetes Care. American diabetes association. 2015; 38 suppl 1: S1-S76.

30. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/000313.htm

31. https://medlineplus.gov/diabetes.html.

32. Morales F, Padilla S, Falconí F. Medicinal plants used in traditional herbal medicine in the province of Chimborazo, Ecuador. African Journal of Traditional, Complementary and Alternative Medicines. 2017; 14(1):10-5.

33. www.differencebetween.net/science/health/difference-between-plants-and-herbs/

34. Karimi A, Majlesi M, Rafieian-Kopaei M, Herbal versus synthetic drugs, belie and facts,J Nephropharmacol.2015; 4(1):27-30.

35. Frith A, Main place : Mamelodi, census 2011.

36. www.rekordeast.co.za/149299/sangomas-givenlicence- to-heal-in-mams/

37. Maggie B. traditional medicines in the treatment of diabetes, diabetes spectr. 2001; 14(3):154-159

38. http://www.polity.org.za/article/medicalpractitioner- versus-traditional-healers-implications-forhiv- aids-policy-2012-02-23

39. Deutschländer MS, Lall N, Van De Venter M. Plant species used in the treatment of diabetes by South African traditional healers: An inventory. Pharmaceutical Biology. 2009 Apr 1; 47(4):348-65.

40. https: //www.emergogroup.com/blog/2017/06/ new-south-african-medical-device-authority-established.

41. Chinedu A, Alani S, Olaide A. Effect of the Ethanolic Leaf Extract of Moringa oleifera on Insulin Resistance in StreptOzotocin Induced Diabetic Rats. Special Issue: Pharmacological and Biological Investigation of Medicinal Plants. Int. J. Plant Sci. 2014; 2(6-1): 5-12.

42. Liverpool J, Alexander R, Johnson M, Ebba EK, Francis S, Liverpool C. Western medicine and traditional healers: partners in the fight against HIV/AIDS. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2004 Jun; 96(6):822.

43. Crawford P. Effectiveness of cinnamon for lowering hemoglobin A1C in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized, controlled trial. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. 2009 Sep 1; 22(5):507-12.

44. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.109-4989

45. Jordaan N, let us regulate ourselves, say traditional healers, 2018, Sowetan live.

46. Brom B, Rees A, Maseko P, the separation of health paradigms, portfolio of committee presentation, the medicine and related substances amendment Bill. The traditional & health science Alliance. 2015.