Abstract

Background: Myelolipoma is a rare benign tumor composed of hematopoietic elements and adipose tissue. It is a nonfunctional tumor that often presents as an infrequent mass, leading to potential misdiagnosis.

Case presentation: This case report presents the case of a 77-year-old man who was referred to the hospital due to a severe productive cough and dyspnea. The symptoms had begun three weeks prior. Radiological examinations, including chest computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), revealed the presence of bilateral paravertebral masses. A biopsy of the left posterior mediastinum tissue, performed under CT scan guidance, showed sheets of trilineage hematopoietic elements surrounded by adipose tissue, which was consistent with myelolipoma. Subsequently, surgical excision of the mass was performed. Pathological examination confirmed the mass as benign and confirmed the nature of myelolipoma.

Conclusions: Myelolipoma should be considered in the differential diagnosis of mediastinal masses, as it is rare but possible. Differential diagnosis of myelolipoma, particularly from extramedullary hematopoiesis, is necessary.

Keywords

Myelolipoma, Extramedullary hematopoiesis, Mediastinal neoplasms, Case report

Background

Myelolipoma is a rare and benign tumor. It is composed of hematopoietic elements and mature adipose tissues that were first reported by Gierke in 1905 [1]. Myelolipoma is usually found in adrenal glands, but approximately 15% of extra-adrenal lesions have been reported [2,3]. In the thorax, this lesion could be located in the pleural, mediastinal, or paravertebral mass [2,4]. The tumors are generally asymptomatic and are found in autopsies or incidentally during surgery [4]. Enlargement may compress surrounding organs and become symptomatic [5]. Herein, we present a case of bilateral mediastinal myelolipoma in a 77-year-old male patient, initially resembling a neurogenic tumor. Additionally, we provide a comprehensive review of the natural history, pathology, para-clinics, diagnosis, management, and prognosis of this lesion.

Case Presentation

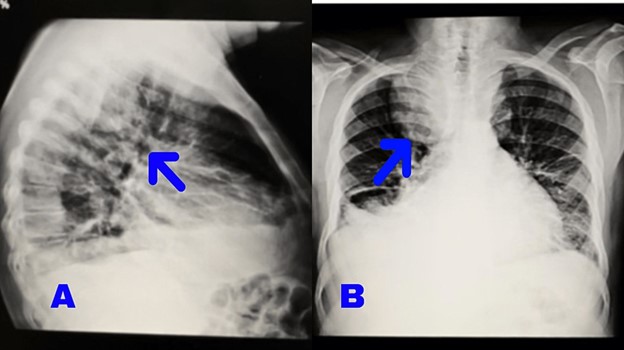

A 77-year-old male presented with severe productive cough symptoms that began three weeks ago. Initially, the patient experienced dry coughs, which progressively became more severe and productive, interfering with daily activities. Dyspnea with functional class 3 (FC 3) also developed over time, with the patient experiencing shortness of breath during daily activities and while lying down. The patient denied having a fever or any systemic symptoms. In the past medical history, the patient had undergone angiography because of exertional dyspnea FC 2 five years ago, and the result was normal angiography. His familial history was negative. He is a nonsmoker and has not been exposed to pollutants in his work or living environment. At the first examination, the patient’s heart rate was 88, respiratory rate was 22, blood pressure was 105/78 mmHg and blood oxygen saturation was 94%. During the physical examination, two-plus pitting edema was observed in the legs and feet, along with varicose veins. Decreased breath sounds were noticed in the lungs, particularly on the right lobe. Clubbing of the fingers was observed. The abdomen was soft, without tenderness or hepatosplenomegaly. Color Doppler sonography of the arteries and veins in the lower limbs revealed atherosclerotic changes in the arterial walls without significant plaque or narrowing. The presence of edema and fluid tracts in the distal part of both lower limbs suggested potential venous insufficiency. Electrocardiography showed evidence of atrial rhythm with a left bundle branch block (LBBB) view. Echocardiography reported biatrial enlargement, normal size of the left and right ventricles, mild mitral valve regurgitation, and a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 60% with a left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVEDd) of 42 mm. A chest X-ray revealed a bilateral mass in the posterior mediastinum, with a larger size on the right side, as well as pleural effusion on the right side (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Posteroanterior and lateral chest X-ray shows bilateral posterior mediastinal mass and right costophrenic angle blunting.

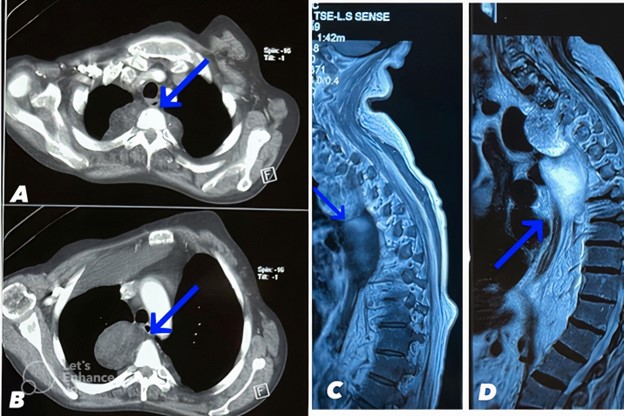

Abdominal and pelvic ultrasound identified right-sided pleural effusion (300-500 cc), leading to a pleural fluid tap under ultrasound guidance. The cytology of the pleural fluid showed several mature lymphomononuclear cells mixed with isolated mesothelial cells in the proteinaceous background. The analysis of the pleural fluid indicated that it was transudative with a lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level of 95 IU/L, protein level of 2 g/dL, and glucose level of 126 mg/dL, confirming the patient's congestive heart failure (CHF). Contrast-enhanced chest CT reveals bilateral paravertebral masses with the larger mass on the right side measuring up to 66 x 46 mm. Both masses contain components of fat and soft tissue density with Hounsfield units ranging from -50 to -100 HU consistent with adipose tissue interspersed with soft tissue density regions of 20- 50 HU. The masses demonstrate heterogeneous enhancement following IV contrast administration. The right paravertebral mass causes mass effect with rightward tracheal deviation and narrowing of the right mainstem bronchus. The masses cause erosion and remodeling of the adjacent T5, T6, and T7 vertebral bodies. Mature adipose tissue comprising the bulk of the masses is identified as hypodense regions with Hounsfield units around -80 HU as indicated by blue arrows on CT images (Figure 2).

Figure 2. A and B: Contrast-enhanced chest CT scan reveals bilateral paravertebral masses (larger size on the right side) containing fat and soft tissue density and shows heterogeneous enhancement. The mature adipose tissue was indicated by blue arrows. C and D: Thoracic MRI in the sagittal plane demonstrated that paravertebral mass has heterogenous high T1 and T2 signal intensity. The mature adipose tissue was indicated by the blue arrow.

A biopsy of the right posterior mediastinum tissue, guided by a CT scan, revealed sheets of trilineage hematopoietic elements between adipose tissue, consistent with myelolipoma. There was no evidence of lymphomatous cells, tumoral lesions, or malignancy in the specimen. Thoracic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) indicated multiple restricted enhancing masses in the bilateral paravertebral region, suggestive of extramedullary hematopoiesis or multiple neurofibromas. Paraclinical findings also indicated heart enlargement and pulmonary hypertension (40 mm). The significant right-sided pleural effusion could be attributed to congestive heart failure, and there were no intrapulmonary nodules or patchy densities.

Due to the compressive effect of the enlarged bilateral mass on the trachea, causing a productive cough, the patient was admitted to the thoracic surgery department for excision of the posterior mediastinal myelolipoma.

After complete preoperative preparations and under general anesthesia, a left double-lumen tube (size 37) was placed, and the patient was positioned in the left lateral decubitus position. An incision was made from the fourth intercostal space to enter the pleural space. A tumoral lesion adjacent to the vertebrae and originating from the nerves. The patient underwent general anesthesia in the left lateral decubitus position to allow optimal exposure of the posterior mediastinum through a standard thoracotomy incision, followed by careful dissection and complete resection of the paravertebral tumor after its identification adjacent to the vertebrae and nerves, with intraoperative frozen section analysis confirming the diagnosis of myelolipoma. It was observed and completely resected. This process involved careful dissection to minimize trauma to adjacent structures and ensure complete tumor removal.

The surgeon chose to perform an open thoracotomy given the large size of the bilateral masses, thoracoscopy is generally suited for smaller lesions that allow adequate visualization and access through port sites. For larger tumors like in this case, open thoracotomy provides better exposure and the ability to control major vessels if bleeding occurs during dissection. The specific location of the tumor within the posterior mediastinum and its proximity to nerves may have made open surgery a safer and more effective choice to ensure complete resection and minimize the risk of nerve injury. The surgeon's experience and comfort with open surgical techniques versus thoracoscopy could also influence the choice of surgical approach.

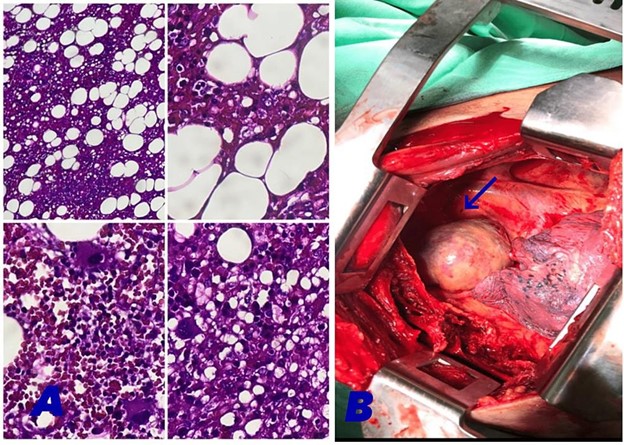

Intraoperative frozen section analysis demonstrates adipose tissue with interspersed trilineage hematopoietic cells including erythroid, myeloid, and megakaryocytic precursors, consistent with myelolipoma. Microscopic examination of permanent sections shows mature adipocytes admixed with hematopoietic cellular elements including myeloid, erythroid, and megakaryocytic precursors, set in a background of loosely arranged fibrous stroma. No significant atypia, increased mitotic activity, or other malignant features are seen. The features are consistent with a benign myelolipoma. The mass is determined to be a Stage 1 tumor according to the mediastinal tumor staging system (Figure 3).

Figure 3. A: Microscopic examination of the resected mediastinal mass tissue shows mature adipose tissue interspersed with hematopoietic elements (H&E stain, original magnification 200X). The mature bone marrow component is indicated by the arrow. This histological pattern is consistent with a benign myelolipoma. No cytological atypia, increased mitotic activity, or other malignant features are identified. The mass is determined to be a Stage 1 benign tumor according to the mediastinal tumor staging system. B: Macroscopic inspection of the tumor during resection showed that it was brown and partially yellow, the section of the tumor is solid and tender, and its boundary is clear. A tumoral lesion measuring 7*9*6.

Post-operative imaging revealed a complete re-extension of the right lung. Chest tube placement is a standard procedure for fluid drainage, and since this was a thoracotomy procedure, a 28-French chest tube was inserted before closing and draining and attached to the seal water drainage so that the lung could expand again. The usual duration is 1-3 days. The chest tube drained the Seroussingin fluid for 2 days and then had a minimum output, so it was removed the day after the 3-day operation.

The patient was discharged without any complications after seven days of hospitalization and post-surgical care. The mass and pleural fluid were sent to pathology for terminal analysis and investigation. The diagnosis confirmed the description of myelolipoma with serious degeneration. Cytopathology of pleural fluid was also reported: some reactive mesothelial cells, mixed acute and chronic inflammatory cells, bloody background, and negative for atypical-dysplastic cells. The follow-up of the patient was performed on an outpatient basis by physical exam, CT scan, and laboratory studies for one year.

Discussion

Myelolipoma is a rare nonfunctional benign tumor that consists of hematopoietic elements and mature adipose tissue. It was first reported by Gierke in 1905 [1]. Myelolipomas are predominantly found in the adrenal gland as solitary lesions, but approximately 15% of cases occur in extra-adrenal locations [2]. Infrequent sites of occurrence include the perirenal region, presacral region, pelvis, liver, spleen, stomach, greater omentum, mediastinum, and lungs [3,5]; thoracic tumors, particularly in the posterior mediastinum, as reported in our case report, are extremely rare [5,6]. Although myelolipomas can happen at any age, extra-adrenal myelolipomas are often found in people older than 40. Our patient is 77 years old, and although extra-adrenal myelolipomas are more common among women (ratio of 2:1), our patient is a male [4]. The size of extra-adrenal myelolipomas can vary between 4 and 15 cm, with an average diameter of 8.3 cm. In our reported case, the tumor size was 7 × 9 × 6 cm [2]. Differentiating extra-adrenal myelolipomas from other fat-containing tumors, especially well-differentiated liposarcomas, can be challenging but is important to avoid unnecessary aggressive treatment. While liposarcomas tend to be larger, more infiltrative tumors, myelolipomas are typically well distributed [10].

Key imaging features that may help distinguish myelolipomas include their rounded shape, presence of fat and myeloid elements interspersed rather than distinct regions, lack of post-contrast enhancement, and non-infiltrative borders. However, a biopsy with pathological analysis is often required for a definitive diagnosis to identify the characteristic trilineage hematopoietic elements [11] As was done in our case. The photo is also included (Figure 3). In contrast to the generally benign course of myelolipoma, liposarcomas have the potential for local recurrence and metastasis, often warranting aggressive treatment including wide surgical resection, chemotherapy, and radiation. Accurate diagnosis is crucial to avoid overly aggressive therapy for benign myelolipomas [14].

However, a conservative approach to probable myelolipomas carries a small risk of missing a low-grade liposarcoma. Multidisciplinary input weighing imaging, biopsy, and clinical behavior may help guide optimal patient-specific management when distinguishing these entities [15].

The exact cause of myelolipoma is not yet fully understood, but several hypotheses have been suggested. Long-term stress may induce the metaplasia of reticuloendothelial cells, and myelolipoma could be caused by embolic materials from the bone marrow [6]. Other theories include residual fetal bone marrow, misplacement of myeloid cells in fetal tumors, and metaplasia of the adrenal gland [2,6,7]. In some cases, myelolipomas have been implicated in association with endocrine disorders such as Cushing's disease, Conn's syndrome, exogenous steroid use, congenital adrenal hyperplasia, pheochromocytoma, adrenal gland cancer or adenoma, and increased cortisol production linked to conditions such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and obesity [6,8]. The underlying cause of extra-adrenal myelolipoma is not well defined [3].

Myelolipomas are typically unilateral and occasionally bilateral. In our patient, there was a bilateral tumor [9]. The tumors often assume a rounded shape without a true capsule; however, the connective tissue surrounding the tumor may form a pseudo capsule [3,5]. Histologically, myelolipomas exhibit a combination of adipose and hematopoietic cells, including myeloid and megakaryocytic elements, particularly lymphocytes and erythroid. Calcification and regions of internal hemorrhage are common in lesions larger than 10 cm, but true reticular sinusoids, bone marrow, and bone spicules are absent [1,9]. Pathological examination reveals mature adipose tissue with scattered areas of hematopoietic tissue, displaying a macroscopic view of light yellow or orange due to the presence of red blood cells or myeloid components. In a red or reddish-brown view, the tissue shows rich marrow hematopoietic elements. In our patient, the cytopathology report shows reactive mesothelial cells, acute and chronic mixed inflammatory cells, a bloody background, and negative for atypical-dysplastic cells [5]. The histopathological features of extra-adrenal myelolipoma are almost indistinguishable from adrenal myelolipoma, except for the rarity of myeloid calcification and hemorrhage [9].

Myelolipomas are typically asymptomatic and are often discovered incidentally during autopsies or surgeries [4]. However, when enlargement occurs, compression of surrounding organs may lead to symptoms. For example, mediastinal lesions can cause coughing, as the patient initially had a cough and dyspnea.; abdominal cases may result in abdominal pain, constipation, and nausea; perirenal lesions may lead to renal failure; and presacral lesions could cause sciatic or back pain.

Rupture and acute hemorrhage, although rare, can present with localized pain, nausea, vomiting, hypotension, and anemia [5,7,9]. Common diagnostic methods include computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [5]. Histological examination helps in interpreting the CT appearance [9]. On CT, myelolipomas appear as neoplasms with adipose tissue density, myeloid components, and evidence of previous hemorrhage. Calcification, while uncommon, may be hyperdense and punctate. Pseudo capsules can also be observed [5,7,9]. Adipose tissue within the lesion exhibits a negative Hounsfield attenuation value, while myeloid tissue appears higher in attenuation. Following contrast administration, enhancement is observed in the myeloid tissue. When adipose and myeloid tissue are intermixed, the attenuation values fall between fat and water [3,9].

Management decisions for myelolipoma depend on several factors including tumor size and location, symptoms, growth rate, and patient comorbidities. For asymptomatic lesions less than 7 cm, conservative monitoring with serial imaging may be reasonable [12]. However, for larger or symptomatic tumors, surgical resection is typically advised to alleviate compressive effects. High surgical risk patients may warrant more conservative approaches. The tumor's proximity to vital structures can also influence surgical decision-making. Ultimately, management should be individualized based on a patient's clinical situation [13].

We made an appropriate choice to perform an open thoracotomy given the large size of the bilateral masses. Due to the high pulmonary artery pressure, the high risk of surgery, the proximity to the subclavian artery, and the possibility of injury, thoracotomy was chosen, which might have been better managed with an open surgical approach due to its size. Thoracoscopy is generally suited for smaller lesions that allow adequate visualization and access through port sites. For larger tumors, such as in this case, open thoracotomy provides better exposure and the ability to control major vessels if bleeding occurs during dissection. The specific location of the tumor within the posterior mediastinum and its proximity to nerves may have made open surgery a safer and more effective choice to ensure complete resection and minimize the risk of nerve injury. The surgeon's experience and comfort with open surgical techniques versus thoracoscopy could also influence the choice of surgical approach. In summary, mediastinal myelolipoma is a rare benign tumor with excellent outcomes after surgical excision. Recurrence is uncommon and malignant transformation has not been reported. Asymptomatic lesions can be monitored conservatively. For symptomatic or rapidly growing tumors, complete surgical resection is the treatment of choice and is often curative.

Conclusion

Extramedullary myelolipoma is a rare condition that should be considered in the differential diagnosis of fat-containing masses, particularly extramedullary hematopoiesis. Efficient utilization of paraclinical methods can expedite the diagnostic process. In this regard, MRI and CT scans can provide valuable insights into the nature of the mass, while a biopsy can further solidify the diagnosis. Prompt decision-making, based on accurate diagnoses, is crucial in managing this condition effectively. While myelolipomas are typically benign, expediting the surgical decision-making process can ultimately help alleviate the compressive effects exerted by the mass and improve patient outcomes.

List of Abbreviations

CT: Computed Tomography; MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging; FC 3: Functional Class 3; LBBB: Left Bundle Branch Block; LVEF: Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction; LVEDd: Left Ventricular End-Diastolic Diameter; LDH: Lactate Dehydrogenase; CHF: Congestive Heart Failure

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate: An Ethics Committee for the publication of this Case Report was not applicable; however, all management methods were in line with relevant guidelines.

Consent for Publication

"Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal."

Availability of Data and Materials

The data are available with the correspondence author and can be reached on request.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

Not applicable.

Authors' Contributions

Dr. Kiana Rezvanfar performed the conceptualization and investigation and drafted the manuscript. Dr. Hadi Karimimobin and Dr. Nasrin Rahmani-Ju were involved in planning and supervising the work, Dr. Farnoosh Sedaghati processed the experimental data and performed the analysis. Dr. Pegah Raisi-Fard designed the figures and was involved in the administration, review, and editing of the manuscript. Dr. Masoud Saadat Fakhr aided in interpreting the results and worked on the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

References

2. Franiel T, Fleischer B, Raab BW, Füzesi L. Bilateral thoracic extraadrenal myelolipoma. European Journal of Cardio-thoracic Surgery. 2004 Dec 1;26(6):1220-2.

3. Temizoz O, Genchellac H, Demir MK, Unlu E, Ozdemir H. Bilateral extra-adrenal perirenal myelolipomas: CT features. Br J Radiol. 2010 Oct;83(994):e198-9.

4. Schittenhelm J, Jacob SN, Rutczynska J, Tsiflikas I, Meyermann R, Beschorner R. Extra-adrenal paravertebral myelolipoma mimicking a thoracic schwannoma. BMJ Case Rep. 2009;2009:bcr07.2008.0561.

5. Shi Q, Pan S, Bao Y, Fan H, Diao Y. Primary mediastinal myelolipoma: a case report and literature review. J Thorac Dis. 2017 Mar;9(3):E219-E225.

6. Sagan D, Zdunek M, Korobowicz E. Primary myelolipoma of the chest wall. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009 Oct;88(4):e39-41.

7. Gao B, Sugimura H, Sugimura S, Hattori Y, Iriyama T, Kano H. Mediastinal myelolipoma. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2002 Jun;10(2):189-90.

8. Sabate CJ, Shahian DM. Pulmonary myelolipoma. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002 Aug;74(2):573-5.

9. Hakim A, Rozeik C. Adrenal and extra-adrenal myelolipomas - a comparative case report. J Radiol Case Rep. 2014 Jan 1;8(1):1-12.

10. Shimoda H, Kijima T, Takada-Owada A, Ishida K, Kamai T. A case of perirenal extra-adrenal myelolipoma mimicking liposarcoma. Urol Case Rep. 2023 Aug 14;50:102523.

11. Benko G, Kopjar A, Plantak M, Cvetko D, Glunčić V, Lukić A. Rare Case of Multiple Perirenal, Extra-Adrenal Myelolipoma: Case Report, Current Management Options, and Literature Review. Case Rep Urol. 2021 Apr 13;2021:6614641.

12. Calissendorff J, Juhlin CC, Sundin A, Bancos I, Falhammar H. Adrenal myelolipomas. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021 Nov;9(11):767-75.

13. Kamran H, Haghpanah A, Dabbaghmanesh MH, Defidio L, Bazrafkan M, Dehghani A, et al. Simultaneous adrenal and retroperitoneal myelolipoma resected by laparoscopic surgery: a challenging case. BMC Urol. 2023 Jul 8;23(1):114

14. Matthyssens LE, Creytens D, Ceelen WP. Retroperitoneal liposarcoma: current insights in diagnosis and treatment. Front Surg. 2015 Feb 10;2:4.

15. Natella R, Varriano G, Brunese MC, Zappia M, Bruno M, Gallo M, et al. Increasing differential diagnosis between lipoma and liposarcoma through radiomics: a narrative review. Explor Target Antitumor Ther. 2023;4(3):498-510.