Abstract

Background: The effect of tumor size on endometrial cancer prognosis and the treatment precision is a challenging issue. This study aimed at assessing the predictive impact of tumor size on endometrial carcinoma aggressiveness parameters and patients' survival.

Methods: 94 patients with surgically treated endometrial cancer in the Radiation Oncology Department of Imam Hossein Hospital, Tehran, Iran between 2010 and 2020 were included for retrospective review of their clinicopathological information and follow-up data. Categorical variables were compared using Chi-squared and Fisher’s exact test, and continuous variables were compared using non-parametric Mann-Whitney U and Kruskal-Wallis tests. Actuarial overall survival and recurrence-free survival were calculated using Kaplan–Meier method.

Results: Patients with tumor size 4 cm and more had higher rates of lymphovascular invasion (LVI) compared to smaller tumors (51.7% vs 13.8%, P<0.001). Additionally, there was a significant correlation between tumor size and FIGO stage (p=0.031). Patients with Carcinosarcoma pathology had marked larger tumor diameter (mean:6.7cm ±2.4), compared with Endometroid (mean:3.9cm ±1.6) (P<001) and Serous adenocarcinoma (mean:2cm ±0.79) (P<001). All seven patients with tumor size 4 cm and more who experienced recurrence in their follow up, had one of the other significant risk factors including high tumor stage(>I), LVI or carcinosarcoma histology. There was not a significant correlation between tumor size and recurrence (p:0.272), overall and recurrence free survival (P:0.754, P:0.169 Respectively).

Conclusion: Although tumor size correlates with other poor prognostic factors of endometrial carcinoma, it is not an independent variable for patients' survival and tumor recurrence. Patients with high tumor size, who experience recurrence, have some other adverse features.

Keywords

Endometrial cancer, Tumor size, Prognosis

List of abbreviations

Endometrial cancer (EC); International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO); lymphovascular Invasion (LVI) ; Recurrence-Free Survival (RFS) ; Overall Survival (OS)

Background

Endometrial cancer (EC) is a prevalent gynecological malignancy, with an increasing incidence of 2.5% every year. Although it is highly curable when found early, still we are expected to some locoregional or distant recurrence of this tumor in some cases with different survival rates [1-3].

Recurrence-free survival and overall survival are the instrumental tools for scientists to quantify the prognosis of patients with EC. In this way, they have been striving to provide uniform terminology of influential factors in patients' survival. There is an array of clinical and pathological prognostic factors suggested for endometrial cancer outcome. Currently, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) 2023 includes tumor invasion (T), nodal status (N) and distant metastases (M), lymphovascular invasion (LVI) and histological types for the staging of endometrial cancer and patient grouping based on their prognosis [4,5]. However, a lot of information has discovered that only relying on these factors is not enough and can lead to undertreatment [6]. Therefore, additional consideration may be needed to improve the management of patients with EC [7].

Tumor size is one of the proposed prognostic factors that still remains as a matter of controversy since 1960 when it was first suggested as a prognostic variable [8]. The ease of tumor diameter measurement without extra resources or high level of competence of pathologists, results in that its significance has been evaluated over the years. Notwithstanding, there are lots of complex issues about the clinically significant tumor diameter and its effect on patients' survival, independently as well as dependently in relation to the other risk factors [9]. The cutoff values for tumor size remain undefined and vary from 2 to 5 cm [9]. Some reports have revealed that there is a non-linear relationship between tumor size and prognosis in EC [10]. Even more confounding findings have been proposed about the reverse effect of small tumor size on the patients' survival [10]. Additionally, the role of tumor size in predictive models suggested for risk estimation of lymph node metastases in EC is not universal. In contrast to the Mayo criteria which includes tumor size, reported by radiological modalities, for prediction of lymph node status, the novel prediction model proposed by Lu et al., does not consider the tumor size defined as the diameter of the largest dimension in their algorithm [11]. Indeed, with all effort to determine tumor size importance in EC, it is not considered a treatment predictor in none of the valid evidence-based protocols [12,13], indicating a need for more studies in this regard.

Here, we performed an observational study aimed at assessing the relation of tumor size to the other prognostic variables, recurrence free survival and overall survival in patients with surgically treated EC.

Methods

Between 2010 and 2020, 110 patients with endometrial cancer were treated in the Radiation Oncology Department of Imam Hossein Hospital in Iran. Data from 94 cases that fulfilled the inclusion criteria of study were evaluated. These criteria were defined as endometrial carcinoma patients who underwent abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with or without pelvic lymph node biopsy/dissection and also had complete postoperative follow-up data.

Patients with FIGO stages IA G1/G2 with LVI or age>60, IA G3 and IB G1/G2 without LVI or age>60 were treated by Brachytherapy alone. External-beam radiotherapy was delivered to the patients with FIGO stages IA G3 and IB G1/G2 with LVI or age>60, and in combination with Brachytherapy in stages IB G3 and II. Cases with FIGO stages III and IV were treated with adjuvant chemotherapy with or without radiation therapy based on tumor site and surgical margin.

Patients' followed-up protocol included clinical, cytological, and imaging studies every three to six months for the first two years, then every six to twelve months for the years three to five and then every year up to ten years.

In this study, clinicopathological factors and survival information were extracted from patients' files. Tumor size, grade, lymphovascular invasion (LVI) and FIGO stage were reported based on pathologic examination. The tumor size was considered as the largest diameter. Patients were staged based on the International Federation of Obstetrics and Gynecology (FIGO) staging of cancer of the endometrium version 2009. Recurrence-free survival (RFS) refers to the time interval from surgical treatment to the time of the first recurrence, or if there is no recurrence, to the last follow-up in living patients. In addition, overall survival (OS) was defined as the interval between the date of surgery and the date of death or last follow-up.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 19 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Continuous variables were expressed in mean ± standard deviation (SD), while categorical variables were expressed in number and percentage. Shapiro–Wilk's test was used to assess normality. Categorical variables were compared using Chi-squared and Fisher’s exact test, and continuous variables were compared using non-parametric Mann-Whitney U and Kruskal-Wallis tests. Actuarial overall survival and recurrence-free survival were calculated using Kaplan–Meier method and the significance between curves assessed by the log-rank test. A two-tailed P value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of patients

Among the 110 patients with endometrial cancer who underwent abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy in Imam Hossein Hospital between 2010 and 2020, 94 patients were included in our study, while 16 patients were excluded due to incomplete information and loss of follow-up. Demographics and clinicopathological characteristics of patients are summarized in Table 1.

|

|

Count |

% |

|

|

Age |

<60 years |

38 |

40.43 |

|

>=60 years |

56 |

59.57 |

|

|

Total |

94 |

100.00 |

|

|

Mean(SD) |

61.45(10.39) |

||

|

(Min , Max) |

(29.0 , 84.0) |

||

|

BMI Kg/m2 |

<25 (normal or underweight) |

18 |

26.87 |

|

25-30 (overweight) |

25 |

37.31 |

|

|

>=30(obese) |

24 |

35.82 |

|

|

Total |

67 |

100.00 |

|

|

Mean(SD) |

28.86(5.27) |

||

|

(Min , Max) |

(21.72 , 50.22) |

||

|

Parity (number of live births) |

0 |

6 |

8.70 |

|

1 |

5 |

7.25 |

|

|

2 |

18 |

26.09 |

|

|

+3 |

40 |

57.97 |

|

|

Total |

69 |

100.00 |

|

|

Tumor Size |

<4cm |

30 |

50 |

|

>=4cm |

30 |

50 |

|

|

Total |

60 |

100 |

|

|

Mean(SD) |

41.78(2.72) |

||

|

(Min , Max) |

(0.9 cm,10 cm) |

||

|

Tumor Type |

Endometroid Adenocarcinoma |

68 |

72.34 |

|

Carcinosarcoma |

10 |

10.64 |

|

|

Clear Cell Carcinoma |

1 |

1.06 |

|

|

Undiff Carcinom |

1 |

1.06 |

|

|

Serous Adenocarcinoma |

12 |

12.77 |

|

|

Mixed Carcinoma |

2 |

2.13 |

|

|

Total |

94 |

100.00 |

|

|

Histological Grade |

1.00 |

28 |

34.15 |

|

2.00 |

20 |

24.39 |

|

|

3.00 |

34 |

41.46 |

|

|

Total |

82 |

100.00 |

|

|

LVI |

Negative |

53 |

59.55 |

|

Positive |

29 |

32.58 |

|

|

Undifined |

7 |

7.87 |

|

|

Total |

89 |

100.00 |

|

|

Lymph node status |

Undetermined |

40 |

42.55 |

|

Positive |

5 |

5.32 |

|

|

Negative |

49 |

52.13 |

|

|

Total |

94 |

100.00 |

|

|

Peritoneal washing cytology |

Undetermined |

15 |

15.96 |

|

Positive |

17 |

18.09 |

|

|

Negative |

62 |

65.96 |

|

|

Total |

94 |

100.00 |

|

|

Involvement of Omentum |

Undetermined |

7 |

7.45 |

|

Positive |

7 |

7.45 |

|

|

Negative |

80 |

85.11 |

|

|

Total |

94 |

100.00 |

|

|

Depth of Invasion |

<50 |

39 |

41.49 |

|

>=50 |

47 |

50.00 |

|

|

Undefined |

8 |

8.51 |

|

|

Total |

94 |

100.00 |

|

|

Adnex |

Undetermined |

4 |

4.26 |

|

Positive |

15 |

15.96 |

|

|

Negative |

75 |

79.79 |

|

|

Total |

94 |

100.00 |

|

|

Segment |

Undetermined |

5 |

5.32 |

|

Positive |

26 |

27.66 |

|

|

Negative |

63 |

67.02 |

|

|

Total |

94 |

100.00 |

|

|

Involvement of Cervix |

Undetermined |

5 |

5.32 |

|

Positive |

19 |

20.21 |

|

|

Negative |

70 |

74.47 |

|

|

Total |

94 |

100.00 |

|

|

Involvement of Vagina |

Undetermined |

5 |

5.32 |

|

Positive |

1 |

1.06 |

|

|

Negative |

88 |

93.62 |

|

|

Total |

94 |

100.00 |

|

|

Involvement of Parameter |

Undetermined |

5 |

5.32 |

|

Positive |

7 |

7.45 |

|

|

Negative |

82 |

87.23 |

|

|

Total |

94 |

100.00 |

|

|

Involvement of Serous |

Undetermined |

5 |

5.32 |

|

Positive |

13 |

13.83 |

|

|

Negative |

76 |

80.85 |

|

|

Total |

94 |

100.00 |

|

|

FIGO_Stage |

1A |

28 |

32.18 |

|

1B |

25 |

28.74 |

|

|

2 |

8 |

9.20 |

|

|

3 |

19 |

21.84 |

|

|

4 |

7 |

8.05 |

|

|

Total |

87 |

100.00 |

|

|

External_Radiotherapy |

Positive |

59 |

62.77 |

|

Negative |

35 |

37.23 |

|

|

Total |

94 |

100.00 |

|

|

Internal_Radiotherapy |

Positive |

41 |

43.62 |

|

Negative |

53 |

56.38 |

|

|

Total |

94 |

100.00 |

|

|

Chemotherapy |

Positive |

40 |

42.55 |

|

Negative |

54 |

57.45 |

|

|

Total |

94 |

100.00 |

|

|

Recurrence |

Negative |

73 |

77.66 |

|

Positive |

21 |

22.34 |

|

|

Total |

94 |

100.00 |

|

|

Outcome |

Alive |

80 |

85.11 |

|

Death |

14 |

14.89 |

|

|

Total |

94 |

100.00 |

|

The mean age of the patients included in the study was 61.45 (min: 29, max: 84) years and 56 (59.57%) of them were more than 60 years old. The average Body Mass Index (BMI) was 28.86 and 26.87 percent of patients had normal or underweight BMI. Six patients (8.7%) had no live births. The most frequent hisitologic type was endometrioid carcinoma (72.34% of cases) and 41.46% had histological grade 3. Twenty eight patients (32.18%) had FIGO stage IA and 25 patients (28.74%) were in stage IB. Invasion to the inferior segment of uterus, adnexa, lymphovascular space, serous, and omentum was observed in 27.66%, 15.96%, 32.58%, 13.83%, and 7.45% of patients, respectively. Seventeen (18.09%) patients had positive peritoneal washing cytology, and in 50% of the patients, the tumor involved more than half of the thickness of the myometrium.

Fifty three patients (56%) underwent surgical lymph node dissection. Radiotherapy, chemotherapy and combination of radiotherapy and chemotherapy have been prescribed to 37 (39%), 8 (8.5%), and 34 (36.5%) patients respectively, while 15 (16%) patients did not receive adjuvant treatment.

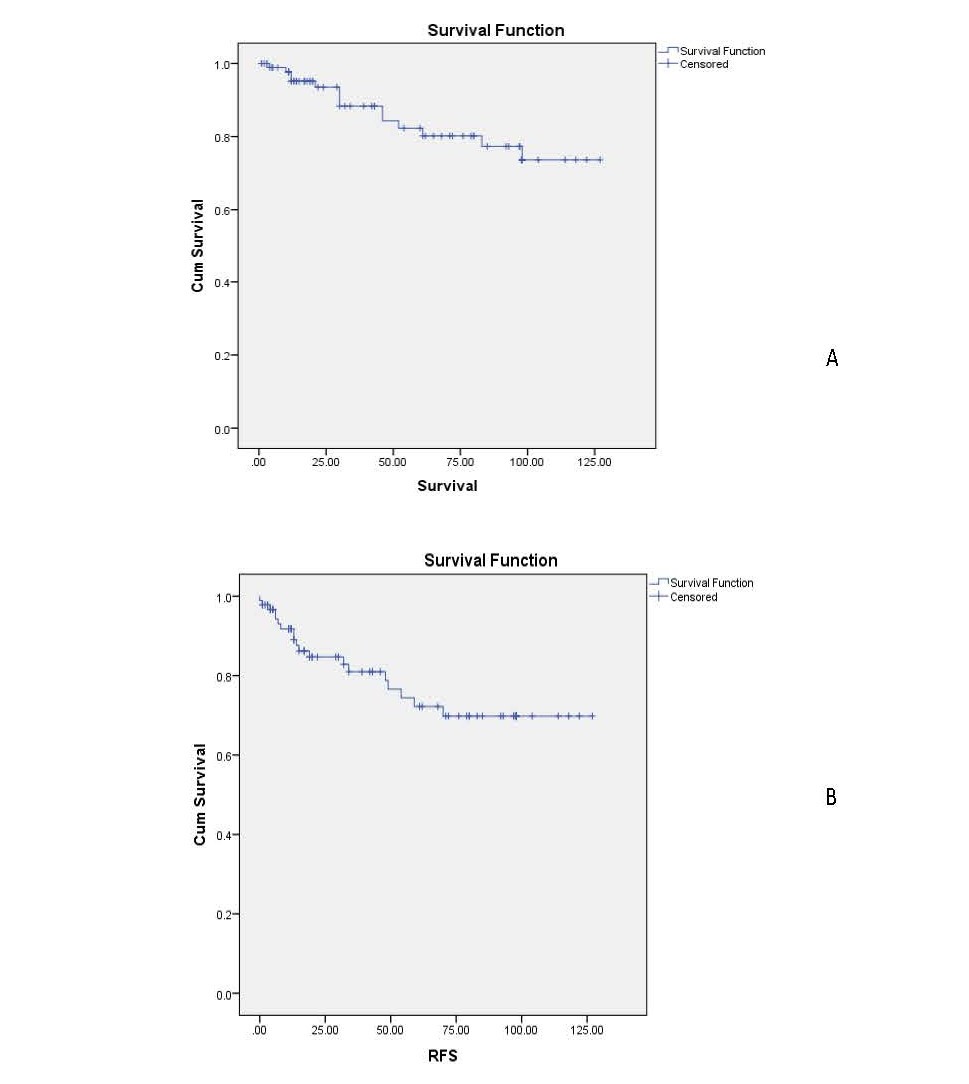

The mean follow-up duration was 49.85 months (minimum 1 and maximum 127 months). Twenty-one patients (22.34%) developed recurrence, and 14 patients (14.89%) died of disease. Median recurrence free survival and median overall survival were 31.0 and 40.5 months, respectively. In the entire cohort, the 3 and 5 years recurrence-free survival was 80% and 70 %, respectively, whereas the 3 and 5 years overall survival was 83% and 80%, respectively (Figures 1a and 1b).

Figure1. Overall (A) and recurrence-free survival (B) for the whole cohort.

Association between tumor size and clinicopathologic factors

The mean tumor's largest diameter was 4.1 (range 0.9–10 cm). Tumor size was divided into two categories ( >4 cm and <4 cm) based on ROC analysis which estimated a tumor cut off 4 cm has the best predictive value of death and recurrnce in our samples. The tumor size was less than 4 cm in 50% of patients. Correlation of all variables with tumor size was assessed (Tables 2 and 3).

|

|

Tumor Size |

|

||

|

Mean Millimeter |

Standard Deviation |

P-Value |

||

|

Age |

<60 |

44.21 |

18.84 |

0.343 |

|

>=60 |

40.66 |

22.22 |

||

|

Tumor Type |

Endometroid Adenocarcinoma |

39.79 |

16.48 |

<0.001 |

|

Carcinosarcoma |

67.78 |

24.89 |

||

|

Serous Adenocarcinoma |

20.14 |

7.90 |

||

|

Grade |

1.00 |

36.47 |

12.13 |

0.588 |

|

2.00 |

42.60 |

20.62 |

||

|

3.00 |

45.65 |

22.69 |

||

|

LVI |

Negative |

35.31 |

17.90 |

0.001 |

|

Positive |

54.47 |

21.54 |

||

|

FIGO Stage |

1A |

32.05 |

15.47 |

0.031 |

|

1B |

41.15 |

14.59 |

||

|

2 |

44.40 |

25.63 |

||

|

3 |

55.38 |

26.65 |

||

|

4 |

55.00 |

19.69 |

||

|

Lymph Node Status |

Positive |

48.33 |

27.54 |

0.846 |

|

Negative |

40.34 |

19.09 |

||

|

Recurrence |

Negative |

39.55 |

19.34 |

0.272 |

|

Positive |

49.85 |

25.86 |

||

|

Outcome |

Alive |

41.71 |

22.39 |

0.478 |

|

Death |

42.25 |

10.31 |

||

|

|

Tumor Size |

P-value |

||||

|

<4.0 |

≥ 4.0 |

|||||

|

Count |

Column N % |

Count |

Column N % |

|||

|

Tumor Type |

Endometroid Adenocarcinoma |

22 |

75.9% |

20 |

69.0% |

|

|

Carcinosarcoma |

0 |

0.0% |

9 |

31.0% |

P<0.001 |

|

|

Serous Adenocarcinoma |

7 |

24.1% |

0 |

0.0% |

|

|

|

LVI |

Negative |

25 |

86.2% |

14 |

48.3% |

|

|

Positive |

4 |

13.8% |

15 |

51.7% |

P<0.001 |

|

|

FIGO Stage |

1A |

14 |

50.0% |

8 |

26.7% |

|

|

>1A |

14 |

50.0% |

22 |

73.3% |

0.065 |

|

The mean tumor size in stage IA, IB, II, III, and IV was 3.2 cm (± 1.5), 4.1 cm (± 1.4), 4.4 cm (± 2.5), 5.5 cm (± 2.6), and 5.5 cm (± 1.9), respectively. There was a significant correlation between tumor size and FIGO stage (p=0.031). Additionally, the incidence of early stage tumors without deep myometrial invasion was 26.7% in patients with a tumor size less than 4 cm against 50% in larger tumors (p:0.065).

The tumor size also correlated with LVI (p<0.001). When LVI was positive, the average tumor size was 5.4 cm (± 2.1) compared with 3.5 cm (± 1.7) in the negative LVI group. Fifty-one percent of patients with tumor size 4 cm and more had LVI compared to 13.8% of smaller tumors (P<0.001).

It was also demonstrated an association between tumor histological type and tumor size (p<0.001). Patients with carcinosarcoma pathology had marked larger tumor diameter (mean: 6.7 cm ± 2.4), compared with endometroid (mean: 3.9 cm ± 1.6) (P<001) and serous adenocarcinoma (mean: 2 cm ± 0.79) (P<001).

Association between tumor size and prognosis

The mean tumor size in patients with recurrence was 4.98 cm (± 2.58). Seven patients with tumor size 4 cm and more experienced recurrence in their follow up and all had one of the other significant risk factors including high tumor stage(>I), LVI or carcinosarcoma histology. Six of these had two risk factors, including deep myometrial invasion and LVI.

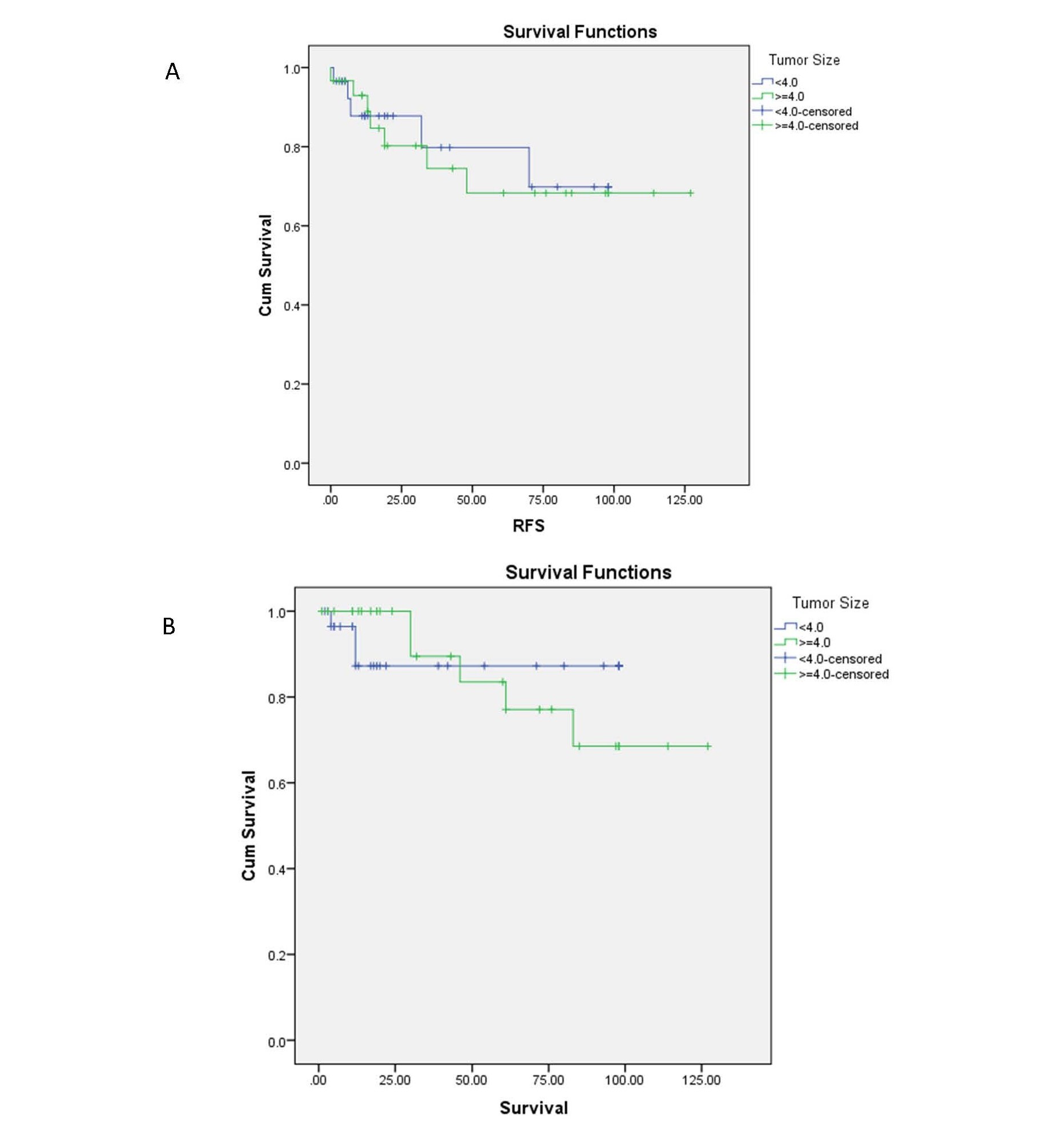

There was not a statistically significant association between tumor size and overall (p:0.754) and recurrence free (p:0.169) survival. The 3 and 5-year OS as well as 3 and 5-year RFS for patients with a tumor size of 4 cm and larger were estimated at 89%, 83%, 80%, and 70%, respectively, and they were 87%, 87%, 85%, and 80% for patients with a tumor size less than 4 cm (Figures 2a and 2b).

Figure 2. The RFS (A) and OS (B) for patients by tumor size.

In subgroup analysis stratifying based on FIGO stages, tumor types and LVI, there was no association between tumor size and patients' outcome, including OS and RFS.

Discussion

Summary of main results

In this analysis, we found two noteworthy findings. First, the tumor size was indeed the indicator of the presence of tumor adverse features and there was a significant correlation between the tumor size and FIGO stage, LVI and tumor histological type. Second, the tumor size was not a predictive factor of disease recurrence and patients’ survival. In other words, large tumors are often associated with other high-risk factors, although this is not always the rule. Our data showed that there is a low possibility of LVI, higher stage disease or aggressive pathology in tumors smaller than 4 cm in size. Therefore, tumor size cannot absolutely predict patient survival and can only be a sign of the presence of tumor related aggressive factors.

Results in the context of published literature

All efforts are made to identify the factors affecting the prognosis of endometrial cancer in order to classify the patients based on relevant risk factors. Tumor size has been an attractive option for discussion in this regard due to the ease and accuracy of measurement, although its relationship with the aggressiveness of the disease has not been proven so far.

The main factor that complicates the assessment of the prognostic and predictive effect of tumor size on endometrial cancer is its correlation with the other poor prognostic factors. We found that tumor size ties with established factors associated with endometrial cancer prognosis, neutralizing the effect of size as an independent factor.

The mean and median tumor size in our study were 4.17 cm and 3.9 cm, respectively, similar to the previous studies. In a series of 703 patients diagnosed with endometrial cancer at the Instituto do Cancer do Estado de Sao Paulo from 2008 to 2018, the reported median tumor size was 4.0 cm [14] and the mean of tumor diameter was 4.26 cm in another study done in 147 patients with endometrial cancer treated at the Gynecologic-Obstetric Clinic of the University of Parma [15]. Our analysis showed that the mean tumor size increased linearly as the tumor stage increased. Consistent with previous reports [15], in the present study, the most significant difference in mean tumor size was demonstrated between stage IA (3.2cm ± 1.5) and IB (4.1 cm ± 1.4) which indicated a relation between tumor size and myometrial invasion. Additionally, patients group with LVI had significantly larger tumors compared with the negative LVI group (5.4 cm ± 2.1 vs 3.5 cm ± 1.7, p<0.001). In a recent retrospective cohort study reported by Oliver-Perez, LVI was more common in larger tumors [16]. We also found out that tumor size was significantly higher in carcinosarcoma compared to the other histological types of tumors. However, the relation between endometrial cancer tumor size and types has not been addressed adequately in prior research. We found that tumor size was not a predictor of recurrence and all patients with tumor size 4 cm and more who experienced recurrence in their follow-up, had one of the other significant risk factors including high tumor stage(>I), LVI or carcinosarcoma histology. These results revealed that the tumor size is an indicator of poor pathologic features of the tumor and higher tumor stage. Therefore, incorporating tumor size in risk stratifying of patients does not add more information.

In the entire cohort of this study, the recurrence-free survival of 3 and 5 years was 80% and 70%, respectively, whereas the 3 and 5 years' overall survival was 83% and 80%, respectively. These values come close to the survival rate reported in the literature for a similar population. The overall survival rates for the 539 women with all stages of histologically confirmed endometrial carcinoma between 2010 and 2015 at St Mary’s Hospital, Manchester were 85% (95% CI 81–88%) at 36 months and 76% (95% CI 71–80%) at 60 months [17]. Similarly, the 5-year survival in Swedish women with endometrial cancer based on the nation-wide Swedish Cancer Registry 2010–2014 was 86% [18].

The association between tumor size and oncological outcome is a controversy. Tumor size was not significantly correlated with recurrence free survival in some studies [14,19,20]. However, others reported a significantly higher rate of recurrence and lower survival in patients with larger tumor size [9,21,22]. In a more detailed review of studies' results, it seems that recent original papers with more comprehensive surgical staging did not demonstrate the relationship between tumor size and patients' prognosis due to more accurate disease stage determination [10,19]. In our study, RFS and OS were not different between patients according to their tumor size (p:0.169 and p:0.754, respctively), where 56% of patients underwent lymph node dissection. The 5-year OS and RFS for patients with tumor size of 4 cm and larger was 83% and 70%, respectively, and it was 87% and 70% for patients with a tumor size less than 4 cm.

Strength and weaknesses

The findings in our study are subject to several limitations including the retrospective nature of the study, a small population and lack of information about molecular characteristics of tumors. Study strengths include long term follow-up and representing a single cancer center.

Implications for further research

There is a fundamental need to identify essential prognostic factors in endometrial cancer and to design a predictive model of recurrence and survival of the patient in order to be able to decide on the intensity of the treatment according to the severity of the disease. Considering that the size of the tumor is one of the factors raised in this field, with some conflicting results, it is necessary to investigate this factor in combination with clinical, pathological, and molecular variables in future studies so that conclusions can be drawn based on higher level of evidence about this item in dealing with endometrial cancer.

Conclusion

We concluded that tumor size correlates with the other poor prognostic factors of endometrial carcinoma, but it is not an independent variable for patients' survival and tumor recurrence.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Guilan University of Medical Sciences with Ethics Code of IR.GUMS.REC.1402.377. Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study. In cases where the patients died, we obtained consent from their immediate families.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Funding

None.

Acknowledgements

None.

References

2. Laban M, El-Swaify ST, Ali SH, Refaat MA, Sabbour M, Farrag N, et al. The Prediction of Recurrence in Low-Risk Endometrial Cancer: Is It Time for a Paradigm Shift in Adjuvant Therapy? Reprod Sci. 2022 Apr;29(4):1068-1085.

3. Zhang S, Gong TT, Liu FH, Jiang YT, Sun H, Ma XX, et al. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Endometrial Cancer, 1990-2017: Results From the Global Burden of Disease Study, 2017. Front Oncol. 2019 Dec 19;9:1440.

4. dos Reis R, Burzawa JK, Tsunoda AT, Hosaka M, Frumovitz M, Westin SN, et al. Lymphovascular Space Invasion Portends Poor Prognosis in Low-Risk Endometrial Cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2015 Sep;25(7):1292-9.

5. Berek JS, Matias‐Guiu X, Creutzberg C, Fotopoulou C, Gaffney D, Kehoe S, et al. FIGO staging of endometrial cancer: 2023. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 2023 Aug;162(2):383-94.

6. Makker V, MacKay H, Ray-Coquard I, Levine DA, Westin SN, Aoki D, et al. Endometrial cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021 Dec 9;7(1):88

7. Koskas M, Amant F, Mirza MR, Creutzberg CL. Cancer of the corpus uteri: 2021 update. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021 Oct;155 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):45-60.

8. Schink JC, Rademaker AW, Miller DS, Lurain JR. Tumor size in endometrial cancer. Cancer. 1991 Jun 1;67(11):2791-4.

9. Jin X, Shen C, Yang X, Yu Y, Wang J, Che X. Association of Tumor Size With Myometrial Invasion, Lymphovascular Space Invasion, Lymph Node Metastasis, and Recurrence in Endometrial Cancer: A Meta-Analysis of 40 Studies With 53,276 Patients. Front Oncol. 2022 Jun 2;12:881850.

10. Hou X, Yue S, Liu J, Qiu Z, Xie L, Huang X, et al. Association of Tumor Size With Prognosis in Patients With Resectable Endometrial Cancer: A SEER Database Analysis. Front Oncol. 2022 Jun 23;12:887157.

11. Lu W, Chen X, Ni J, Li Z, Su T, Li S, et al. A Model to Identify Candidates for Lymph Node Dissection Among Patients With High-Risk Endometrial Endometrioid Carcinoma According to Mayo Criteria. Front Oncol. 2022 Jun 20;12:895834.

12. Oaknin A, Bosse TJ, Creutzberg CL, Giornelli G, Harter P, Joly F, et al. Electronic address: clinicalguidelines@esmo.org. Endometrial cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2022 Sep;33(9):860-877.

13. Abu-Rustum N, Yashar C, Arend R, Barber E, Bradley K, Brooks R, et al. Uterine Neoplasms, Version 1.2023, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2023 Feb;21(2):181-209.

14. Anton C, Kleine RT, Mayerhoff E, Diz MDPE, Freitas D, Carvalho HA, et al. Ten years of experience with endometrial cancer treatment in a single Brazilian institution: Patient characteristics and outcomes. PLoS One. 2020 Mar 5;15(3):e0229543.

15. Berretta R, Patrelli TS, Migliavacca C, Rolla M, Franchi L, Monica M, et al. Assessment of tumor size as a useful marker for the surgical staging of endometrial cancer. Oncol Rep. 2014 May;31(5):2407-12.

16. Oliver-Perez MR, Magriña J, Villalain-Gonzalez C, Jimenez-Lopez JS, Lopez-Gonzalez G, Barcena C, et al. Lymphovascular space invasion in endometrial carcinoma: Tumor size and location matter. Surg Oncol. 2021 Jun;37:101541.

17. Njoku K, Barr CE, Hotchkies L, Quille N, Wan YL, Crosbie EJ. Impact of socio-economic deprivation on endometrial cancer survival in the North West of England: a prospective database analysis. BJOG. 2021 Jun;128(7):1215-1224.

18. Herbst F, Dickman PW, Moberg L, Högberg T, Borgfeldt C. Increased incidence and improved survival in endometrial cancer in Sweden 1960-2014: a population-based registry survey. BMC Cancer. 2023 Mar 27;23(1):276.

19. Çakır C, Kılıç İÇ, Yüksel D, Karyal YA, Üreyen I, Boyraz G, et al. Does tumor size have prognostic value in patients undergoing lymphadenectomy in endometrioid-type endometrial cancer confined to the uterine corpus? Turk J Med Sci. 2019 Oct 24;49(5):1403-1410.

20. Doll KM, Tseng J, Denslow SA, Fader AN, Gehrig PA. High-grade endometrial cancer: revisiting the impact of tumor size and location on outcomes. Gynecol Oncol. 2014 Jan;132(1):44-9.

21. Mahdi H, Munkarah AR, Ali-Fehmi R, Woessner J, Shah SN, Moslemi-Kebria M. Tumor size is an independent predictor of lymph node metastasis and survival in early stage endometrioid endometrial cancer. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2015 Jul;292(1):183-90.

22. Chattopadhyay S, Cross P, Nayar A, Galaal K, Naik R. Tumor size: a better independent predictor of distant failure and death than depth of myometrial invasion in International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics stage I endometrioid endometrial cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2013 May;23(4):690-7.