Abstract

Background: Currently, newer strategies are being implemented regarding WATCHMAN placement in the community hospital, such as same-day discharge (SDD). The safety of this protocol needs to be further assessed.

Objective: The study aimed to evaluate the outcomes of SDD versus non-SDD in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation who underwent WATCHMAN placement by comparing baseline demographics and post-procedure outcomes.

Methods: We retrospectively reviewed four hundred thirty patients who underwent the WATCHMAN procedure in a community hospital between July 2019 and September 2024. Outcomes studied included readmission and mortality rates within thirty days following WATCHMAN placement.

Results: From the 430 patients that were reviewed, 284 patients had non-SDD and 146 had SDD. All-cause readmissions within 30 days of discharge were significantly lower in the SDD group compared to that of the non-SDD (15.8% vs 25.7%, p = 0.02). Additionally, there was a statistically significant difference between the percentage of SDD versus non-SDD patients with thirty-day readmissions due to infectious etiologies (1.37% vs 5.99%; p=0.03).

Conclusion: The all-cause readmission rates of SDD vs non-SDD patients suggests that SDD is a safe and acceptable approach amongst patients undergoing LAAC in the community hospital setting with limited resources.

Keywords

Arrhythmia, Atrial fibrillation, Left atrial appendage closure, Same-day discharge

Abbreviations

AF: Atrial Fibrillation; SDD: Same Day Discharge; LAAC: Left Atrial Appendage Closure; LAA: Left Atrial Appendage; TEE: Transesophageal Echocardiography; CHF: Congestive Heart Failure

Introduction

The prevalence of atrial fibrillation (AF) has continued to rise throughout the 21st century due to increased life expectancy and improved survival among patients with chronic comorbidities [1]. Left atrial appendage closure (LAAC) has emerged as a pivotal strategy for stroke prevention in patients with nonvalvular AF who are not ideal candidates for long-term anticoagulation with Vitamin K antagonists or Factor Xa inhibitors [2]. Studies have reported seven-day procedure-related complication rates of 8.7%, 4.2%, and 2.7% in the PROTECT-AF, PREVAIL, and EWOLUTION trials, with perioperative complication rates at an estimated rate of 1.19% [3–6]. The improved procedural safety of LAAC, increased operator experience, and procedural refinement has prompted increasing interest in same-day discharge (SDD) protocols as an alternative to the traditional overnight hospital observation.

This shift is particularly relevant in community hospital settings, where resource limitations—especially in bed availability—demand efficient patient flow. Prolonged or preventable hospitalizations contribute substantially to healthcare costs, with avoidable inpatient stays accounting for billions of dollars annually in the United States [6]. Furthermore, extended hospitalizations are not without risk. Each additional day is associated with an increased likelihood of adverse events such as nosocomial infections, deconditioning, and medication-related complications [6].

Recent evidence suggests that same-day discharge following LAAC may be both safe and feasible in selected patients [7]. In this single-center retrospective study conducted at a resource-constrained community hospital, we compared perioperative and postoperative outcomes between patients undergoing LAAC with SDD and those admitted to the hospital for overnight observation. By examining the balance between safety and efficiency, we aim to contribute meaningful data to guide discharge planning and optimize the use of limited healthcare resources.

Methods

Patient selection

The following retrospective study consisted of patients who underwent LAAC with the WATCHMAN device between July 2019 to September 2024 at a community hospital that acts as a tertiary center. Prior to data collection, this study was approved by the hospital system’s institutional review board, and the requirement for informed consent was waived due to the use of de-identified data. Patients were deemed eligible for LAAC if they were eighteen years or older and had a minimum HAS-BLED score of 3.

Procedure and monitoring

One electrophysiologist (I.A.) performed all of the LAAC procedures with the WATCHMAN devices that were provided by Boston Scientific. The procedures were performed under general anesthesia with transesophageal echocardiography (TEE). The procedure was catheter-based which required right and left femoral vein access. Vascular access was obtained via ultrasound utilizing a 16 French sheath in the right femoral vein and 9 French sheath in the left femoral vein. All patients were administered 1500 mg of cefuroxime for intraoperative antibiotics and anticoagulated with heparin to achieve a clotting time between 200 and 300 seconds. For LAAC performed prior to 2021, manual pressure was applied to access sites after the procedure to achieve hemostasis. Starting from 2021, hemostasis was achieved using a VASCADE closure device, which is an extravascular, bioabsorbable femoral access closure system that is easy to use, leaves no permanent components behind, and has demonstrated safety and efficacy in a wide range of patients. This system was approved by the FDA in 2013 and combines a collapsible disc technology with a thrombogenic resorbable collagen patch in an integrated design.

Primary and secondary outcomes

The primary outcome was all-cause readmissions within 30 days of discharge after LAAC for either rapid ventricular rate, other abnormal symptomatic arrhythmias, heart failure exacerbations, infectious causes, bleeding, acute CVA, acute coronary syndrome, or other non-cardiac reasons. The secondary outcomes include all-cause 30-day mortality, procedure length, device size, and peri-device leaks on repeat TEE 45 days after implantation.

Statistical analysis

Patient characteristics, medical history, and adverse outcomes between SDD and non-SDD groups were compared using the student’s t-test (for normally distributed data) or Wilcoxon rank sum test (for non-normally distributed data) for continuous variables. For categorical variables, the chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact tests (when 25% of the contingency table cells had expected counts less than 5) were performed. Data distribution was assessed through visual inspection (using histograms and P-P plots) and the Shapiro-Wilk test for normality. Simple and multiple logistic regression models were then used to examine factors associated with adverse outcomes. Factors with a p<0.20 in the simple logistic regression were included in the initial model for multiple logistic regression. Backward selection was used to determine the final model. Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05 (two-sided). All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

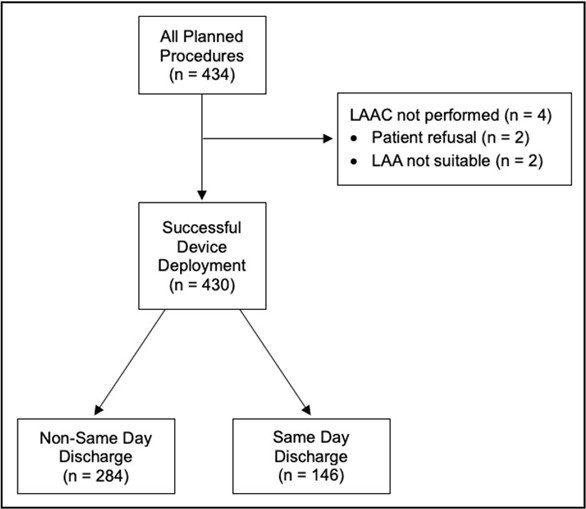

In this study, 434 patients were evaluated and agreed to undergo LAAC using the WATCHMAN device between July 2019 and September 2024. The procedure was performed on a total of 430 patients. Two patients did not want to pursue the procedure, with one of these patients opting out after a non-cardiac related infection that delayed the planned WATCHMAN placement. Two other patients had intraoperative TEEs which revealed unsuitable left atrial appendage (LAA) anatomy. Amongst the 430 patients who had successful LAAC with WATCHMAN, 146 (34%) of them underwent SDD while 284 (66%) of them underwent additional monitoring. The primary and secondary outcomes were analyzed for these final 430 patients.

Baseline demographics

The two groups had similar age and body mass index. There were generally more males than females within the two groups, but the overall proportion of females was higher in the non-SDD patients (47.2% vs 34.2%, p=0.01). Comorbid conditions, including hypertension, obstructive lung disease, history of bleeds, and history of prior strokes or TIA were comparable across both patient cohorts. The SDD group had a greater proportion of patients with history of coronary artery disease and prior myocardial infarction. The non-SDD group had a larger percentage of congestive heart failure and diabetes mellitus. Despite these differences, the distribution of CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED scores was similar across both groups. The rate of chronic kidney disease was similar in both groups, but the non-SDD patients had a slightly lower calculated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) (69.6 vs 75.7, p=0.003). The medications taken by patients up until the planned procedure were comparable in both cohorts except for dual-antiplatelet therapy, which was higher in the SDD group. This is consistent with the higher number of past myocardial infarctions seen in these patients. No differences were observed with the procedural characteristics including duration, device size, peri-device leak, or LAA thrombus on follow-up TEE at 45-days following device deployment.

|

Characteristic |

SDD (n = 146) |

Non-SDD (n = 284) |

p-value |

|

Age, yrs |

75.6±7.9 |

76.6±7.8 |

0.22a |

|

Gender |

|

|

0.01 |

|

Male |

96 (65.8%) |

150 (52.8%) |

|

|

Female |

50 (34.2%) |

134 (47.2%) |

|

|

CHA2DS2-VASc |

|

|

0.35c |

|

2 |

0 (0.0%) |

1 (0.4%) |

|

|

3 |

22 (15.1%) |

36 (12.7%) |

|

|

4 |

47 (32.2%) |

71 (25.0%) |

|

|

5 |

50 (34.2%) |

98 (34.5%) |

|

|

6 |

21 (14.4%) |

58 (20.4%) |

|

|

7 |

6 (4.1%) |

13 (4.5%) |

|

|

8 |

0 (0.0%) |

5 (1.8%) |

|

|

9 |

0 (0.0%) |

2 (0.7%) |

|

|

HAS-BLED |

|

|

0.17c |

|

2 |

4 (2.7%) |

15 (5.3%) |

|

|

3 |

43 (29.5%) |

72 (25.5%) |

|

|

4 |

59 (40.4%) |

122 (43.0%) |

|

|

5 |

35 (24.0%) |

50 (17.6%) |

|

|

6 |

5 (3.4%) |

21 (7.4%) |

|

|

7 |

0 (0.0%) |

3 (1.2%) |

|

|

BMI |

31.08±6.88 |

32.38±8.46 |

0.23b |

|

Congestive Heart Failure |

86 (58.9%) |

195 (68.7%) |

0.04 |

|

Hypertension |

132 (90.4%) |

245 (86.3%) |

0.22 |

|

Diabetes Mellitus |

46 (31.5%) |

128 (45.1%) |

0.007 |

|

Chronic Kidney Disease |

35 (24.0%) |

87 (30.6%) |

0.15 |

|

eGFR |

75.7±17.4 |

69.5±21.7 |

0.002a |

|

Coronary Artery Disease |

103 (70.6%) |

168 (59.2%) |

0.02 |

|

Prior Myocardial Infarction |

66 (45.2%) |

86 (30.3%) |

0.002 |

|

Previous Stroke / TIA |

40 (27.4%) |

89 (31.3%) |

0.4 |

|

Obstructive Lung Disease |

51 (34.9%) |

124 (43.7%) |

0.08 |

|

Hx of Bleed |

|||

|

GI |

45 (30.8%) |

111 (39.1%) |

0.09 |

|

Intracranial |

8 (5.5%) |

31 (10.9%) |

0.06 |

|

Other |

50 (34.3%) |

85 (29.9%) |

0.36 |

|

Hemoglobin |

12.9±1.9 |

12.4±2.0 |

0.02a |

|

Platelets |

246.9±91.6 |

244.3±93.8 |

0.78a |

|

Prior Aspirin |

117 (80.1%) |

212 (74.7%) |

0.2 |

|

Prior DAPT |

87 (59.6%) |

119 (41.9%) |

0.001 |

|

Beta Blocker |

119 (81.5%) |

231 (81.3%) |

0.97 |

|

SGLT2i |

27 (18.5%) |

35 (12.3%) |

0.08 |

|

ACEi / ARB / ARNI |

88 (60.3%) |

146 (51.4%) |

0.08 |

|

MRA |

25 (17.1%) |

53 (18.7%) |

0.7 |

|

Digoxin |

2 (1.4%) |

9 (3.2%) |

0.34c |

|

Nitrates |

20 (13.7%) |

31 (10.9%) |

0.4 |

|

Mean and standard deviation were presented for numeric variables, while percentages were presented for categorical variables. BMI represents body mass index; SDD, same day discharge; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; TIA, transient ischemic attack; GI, Gastrointestinal; DAPT, dual-antiplatelet therapy; SGLT-2i, SGLT2 inhibitors; ACEi, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB, angiotensin receptor blockers; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist. P-values were obtained using chi-squared tests, unless specified, aT-Test, bWilcoxon rank sum test, and cFisher’s exact test. |

|||

Primary and secondary outcomes

All-cause readmissions within 30 days of discharge were significantly lower in the SDD group compared to that of the non-SDD (15.8% vs 25.7%, p=0.02). For both patient cohorts, the majority of readmissions were due to cardiac-related reasons (30.4% for SDD and 32.9% for non-SDD) which included CHF exacerbations, rapid ventricular response, other arrhythmias, acute coronary syndrome, and Type 2 NSTEMI. Patients who underwent SDD were also rehospitalized for bleeding (21.8%), musculoskeletal reasons (17.4%), and CVA (13%).

Non-SDD patients had readmissions for infection (23.3%), bleeding (16.4%), and syncope (16.4%). Notably, patients discharged after further monitoring had higher rates of readmissions due to infectious-related causes than those discharged on the same day (23.3% vs 8.7%, p=0.03). Readmissions from all other causes were comparable across both groups.

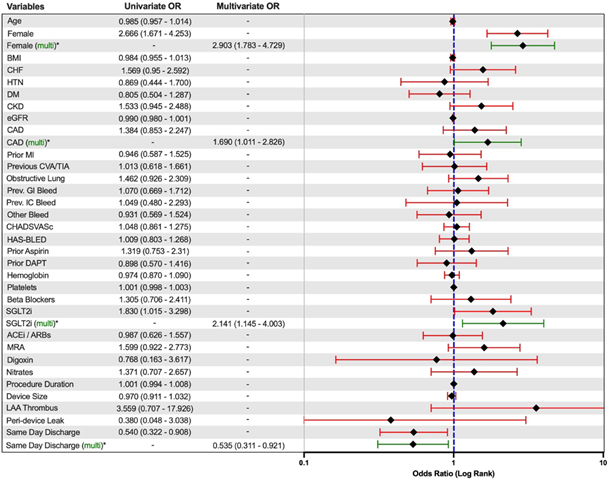

The overall mortality rate for both patient groups was comparable and low at 1.4% in SDD and 0.7% in non-SDD (p=0.50). A univariate and multivariate logistical regression model for readmission rates within 30 days of discharge was used to further assess the likely contributory risk factors. There were higher rates of readmissions for patients who were female (odds ratio [OR] 2.903, 95% CI – 1.783 to 4.729), who had a prior diagnosis of CAD (odds ratio [OR] 1.690, 95% CI – 1.011 to 2.826), or were on an SGLT2i (odds ratio [OR] 2.141, 95% CI – 1.145 to 4.003) prior to the LAAC procedure. SDD (odds ratio [OR] 0.535, 95% CI – 0.311 to 0.921) was associated with reduced rates of readmissions within 30 days of WATCHMAN device deployment.

|

Readmissions and Mortality |

SDD (n = 146) |

Non-SDD (n = 284) |

p-value |

|

All-cause readmissions within 30 days |

23 (15.8%) |

73 (25.7%) |

0.02 |

|

Cardiac |

7 (30.4%) |

24 (32.9%) |

0.83 |

|

Heart Failure Exacerbation |

1 (4.3%) |

8 (11%) |

0.68 a |

|

Rapid Ventricular Response |

5 (21.8%) |

8 (11%) |

0.19 |

|

Arrhythmia |

0 (0.0%) |

3 (4.1%) |

0.99 a |

|

Acute Coronary Syndrome |

1 (4.3%) |

2 (2.7%) |

0.56 a |

|

Type 2 NSTEMI |

0 (0.0%) |

3 (4.1%) |

0.99 a |

|

Infectious |

2 (8.7%) |

17 (23.3%) |

0.03 a |

|

Bleed |

5 (21.8%) |

12 (16.4%) |

0.56 |

|

Gastrointestinal |

1 (4.3%) |

4 (5.5%) |

0.99 a |

|

Groin Hematoma |

2 (8.7%) |

5 (6.8%) |

0.67 a |

|

Other |

2 (8.7%) |

3 (4.1%) |

0.59 a |

|

CVA / TIA |

3 (13.0%) |

3 (4.1%) |

0.15 a |

|

Presyncope / Syncope |

2 (8.7%) |

12 (16.4%) |

0.51 a |

|

Musculoskeletal |

4 (17.4%) |

5 (6.8%) |

0.21 a |

|

All-cause mortality within 30 days |

2 (1.4%) |

2 (2.7%) |

0.61 a |

|

Values presented are percentages for categorical variables. SDD: Same-Day Discharge; NSTEMI: Non ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction; CVA: Cerebral Vascular Accident; TIA: Transient Ischemic Attack. P-values were obtained using chi-squared tests, unless specified, aFisher’s exact test. |

|||

|

Procedure Characteristics |

SDD (n = 146) |

Non-SDD (n = 284) |

p-value |

|

Procedure time, min |

105.8±29.7 |

109.8±32.7 |

0.21a |

|

Device Size, mm |

26.4±3.8 |

26.4±3.7 |

0.89 a |

|

LAA Thrombus on f/u TEE |

1 (0.7%) |

5 (1.8%) |

0.67 b |

|

Peri-Device Leak > 5mm at f/u TEE |

5 (3.4%) |

5 (1.8%) |

0.32 b |

|

Mean and standard deviation were presented for numeric variables, while percentages were presented for categorical variables. SDD: Same-Day Discharge; TEE: Transesophageal Echocardiogram. P-values were obtained using aT-Test, or bFisher’s exact test. |

|||

Discussion

This single-center retrospective study demonstrates that SDD following LAAC with the WATCHMAN device is both a safe and feasible strategy. Among the 430 patients who underwent successful LAAC, 146 (34%) were discharged the same day, while 284 (66%) remained hospitalized for continued monitoring. Procedural outcomes and short-term safety remained favorable across both cohorts despite baseline differences.

The demographic and clinical profiles of the two groups were largely similar, but important distinctions were observed. Patients in the SDD cohort were more often male and had higher rates of coronary artery disease, prior myocardial infarction, and dual antiplatelet therapy use.

The non-SDD group had more patients with congestive heart failure, diabetes mellitus, and reduced estimated glomerular filtration rate. Despite these differences, both groups had comparable CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED scores, indicating similar baseline risks for stroke and bleeding. Additionally, these comorbidities did not affect the 30-day readmission rate, as seen by the linear regression analysis in Figure 2. The population in our retrospective study had several similarities and differences when compared to those studied in the previous landmark trials regarding LAAC. The mean age of our patient cohort is higher than that of the PROTECT-AF, PREVAIL, EWOLUTION, and PRAGUE trials [6,8–10]. However, it is similar to previous literature demonstrating the feasibility of SDD [7]. Patient cohorts from both PRAGUE and EWOLUTION utilized CHA2DS2-VASc and had lower stroke risk compared to our patient cohort; however, the scores were similar when compared to the population in PREVAIL and the National Cardiovascular Data LAA Occlusion Registry [6,9–11]. Additionally, bleeding risk was also less in the populations of PRAGUE, EWOLUTION, the National Cardiovascular Data LAA Occlusion Registry when compared to our population [6,10,11]. These comparisons suggest that our study population reflects a higher-risk cohort than those previously studied.

Figure 1. Flow of methods depiction.

Within thirty days of discharge, all-cause readmissions were significantly lower in the SDD group compared to that of the non-SDD (15.8 vs 25.7%, p= 0.02). When comparing causes for readmission between both groups, there was a significant difference between SDD and non-SDD populations regarding readmission rates due to infectious causes (8.7% vs 23.3%, p=0.03). It is important to note that there was no significant difference in LAA thrombus formation or peri-device leak greater than 5 mm on follow-up TEE, making it less likely that there was a form of device-related infection occurring. Infection rates related to LAAC and associated endocarditis have been documented to be exceedingly rare [6,10,13]. Currently, the most common complications associated with LAAC are pericardial effusion formation, bleeding, and device-related issues, with no clear correlation between rate of effusion formation and infection itself [14]. Furthermore, the majority of pericardial effusions that occur following LAAC have been suggested to be more related to the type of device used and its diameter [15]. With this study being performed at a single center and only the WATCHMAN device being used, there is less likelihood that this played any sort of role in the 30-day readmission rate differences. Also, our population’s most common etiology of readmission was cardiac-related, with heart failure exacerbation and rapid ventricular response being the most common causes, which may have been a function of our population’s significantly higher rate of CHF compared to those population in previous literature [6–10]. Multivariate regression analysis confirmed that SDD was independently associated with reduced odds of 30-day readmission (OR 0.535, 95% CI: 0.311–0.921). Other predictors of readmission included female sex (OR 2.903, 95% CI: 1.783–4.729), coronary artery disease (OR 1.690, 95% CI: 1.011–2.826), and preprocedural use of SGLT2 inhibitors (OR 2.141, 95% CI: 1.145–4.003). While infections such as urinary tract infections can be higher in the female population and those on SGLT-2 inhibitors, the higher rates of diabetes and CHF as well as reduced kidney function in the non-SDD group may also have contributed. Additionally, patients selected for SDD are more likely to be medically optimized, have fewer comorbidities, and demonstrate stable post-procedural status.

Conversely, patients requiring overnight hospitalization often have higher medical complexity or early post-procedural concerns that prompt extended monitoring; these characteristics, including frailty, chronic disease burden, or limited functional reserve, are known to predispose to infection within the subsequent 30 days. Despite this, mortality at 30 days was low and not significantly different between cohorts (1.4% in SDD vs. 0.7% in non-SDD, p = 0.50).

Intraoperative and postoperative characteristics; namely the procedure time, device size, and rates of LAA thrombus and peri-device leak on follow-up TEE used, had no significant difference when comparing the SDD and non-SDD groups. Postoperative complications were low in both groups, most likely due to careful size selection of the LAAC device. Current recommendations for WATCHMAN occluder device usage for LAAC include usage on maximal LAA orifice diameters between 17–31 mm [16]; however, oversizing has become more common due to documented lowered risks of device leak and device embolization [11]. A major reason for this risk reduction with oversizing may be that volume loading increases the LAA dimensions, an effect that does not occur during the fasting state in which the pre-procedure TEE is performed [17]. Volume loading may be utilized more frequently in the future to more accurately predict the proper LAAC device and bring about the same benefit as oversizing [18]. Post-procedural increases in LAA diameter by 1 to 3 mm and reductions in device compression at follow-up compared to immediately post-implantation have been observed [18,19]. With increasing procedural experience and standardized techniques, complication rates have remained low, which was reflected across both SDD and non-SDD patients in this study.

Limitations

Several limitations exist regarding the study performed. First off, this observational study has several inherent limitations, such as risk of selection bias and confounding variables due to lack of randomization. While our study did successfully demonstrate that SDD following LAAC may be safe and medically appropriate as shown in previous studies, the differences in demographics that exist between the SDD and non-SDD groups may act as potential confounders that were not accounted for in the multiple logistic regression [2]. This includes certain demographic features, such as ethnicity or socioeconomic status. Due to this study being limited to a single-center, there is a possibility that one or several demographics that were not studied could have potentially played a role in complication development and hospital re-admission rates. Additionally, socioeconomic factors could not be fully accounted for in this single-center analysis because detailed insurance and socioeconomic data were not accessible due to HIPAA-related restrictions, limiting our ability to control for these potential confounders in the comparison between SDD and non-SDD patients. Ultimately, prospective studies would be necessary in the future that control for these demographic features as well as other confounding variables found in the multivariate linear regression analysis, such as gender, previous cardiac history, and pre-procedural medications that may have influenced the outcomes.

Since this analysis was conducted at a single institution, the findings may reflect center-specific practices, patient selection patterns, procedural workflows, or discharge protocols that differ from those at other hospitals. As a result, the observed differences between SDD and non-SDD patients may not be fully generalizable to broader or more diverse populations. Multi-center studies are needed to confirm whether these outcomes persist across varying practice environments.

A major outcome that was not included in this study was the number of leaks following LAAC that were between 0–5 mm. Data collected from the National Cardiovascular Data LAAO Registry has suggested that leaks of this size were associated with higher incidence of thromboembolic and bleeding events [20,21].

Conclusion

This retrospective observational study was able to successfully demonstrate the safety and feasibility of SDD among patients that underwent LAAC that was found in previous studies, while doing so with a much greater power. Intraoperative and post-operative complication rates within thirty days in the SDD group were not higher than the non-SDD group, highlighting how the safety profile is maintained with the SDD strategy. Furthermore, these findings were demonstrated at a community hospital in a rural setting, highlighting the maintenance of efficacy in a place with limited resources. While SDD following LAAC has the potential to lower expenditures for both hospital and patients while improving satisfaction, future randomized controlled trials would be necessary to further validate these findings while also studying a larger, more diverse population to more effectively evaluate the long-term benefits and risks of SDD inpatients undergoing LAAC.

References

2. Granger CB, Alexander JH, McMurray JJV, Lopes RD, Hylek EM, Hanna M, et al. Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;365(11):981–92.

3. Reddy VY, Doshi SK, Kar S, Gibson DN, Price MJ, Huber K, et al. 5-year outcomes after left atrial appendage closure: from the PREVAIL and PROTECT AF trials. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2017;70(24):2964–75.

4. Osmancik P, Herman D, Neuzil P, Hala P, Taborsky M, Kala P, et al. Left atrial appendage closure versus direct oral anticoagulants in high-risk patients with atrial fibrillation. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2020;75(25):3122–35.

5. Chen C, Chen Y, Qu L, Su X, Chen Y. 3-year outcomes after left atrial appendage closure in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: cardiomyopathy related with increased death and stroke rate. BMC Cardiovascular Disorders. 2023;23(1):27.

6. Hauck K, Zhao X. How dangerous is a day in hospital? A model of adverse events and length of stay for medical inpatients. Medical Care. 2011;49(12):1068–75.

7. Boersma LV, Ince H, Kische S, Pokushalov E, Schmitz T, Schmidt B. Evaluating real-world clinical outcomes in atrial fibrillation patients receiving the WATCHMAN left atrial appendage closure technology. Circulation: Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology. 2019;12(4):e006841.

8. Tan BEX, Boppana LKT, Abdullah AS, Chuprun D, Shah A, Rao M, et al. Safety and feasibility of same-day discharge after left atrial appendage closure with the WATCHMAN device. Circulation: Cardiovascular Interventions. 2021;14(1):e009669.

9. Reddy VY, Holmes D, Doshi SK, Neuzil P, Kar S. Safety of percutaneous left atrial appendage closure: results from the Watchman left atrial appendage system for embolic protection in patients with AF (PROTECT AF) clinical trial and the Continued Access Registry. Circulation. 2011;123(4):417–24.

10. Holmes DR Jr, Kar S, Price MJ, Whisenant B, Sievert H, Doshi SK, et al. Prospective randomized evaluation of the Watchman left atrial appendage closure device in patients with atrial fibrillation versus long-term warfarin therapy: the PREVAIL trial. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2014;64(1):1–12.

11. Nielsen-Kudsk JE, Korsholm K, Damgaard D, Valentin JB, Diener HC, Camm AJ, et al. Clinical outcomes associated with left atrial appendage occlusion versus direct oral anticoagulation in atrial fibrillation. JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions. 2021;14(1):69–78.

12. Sandhu A, Varosy PD, Du C, Aleong RG, Tumolo AZ, West JJ, et al. Device-sizing and associated complications with left atrial appendage occlusion: findings from the NCDR LAAO Registry. Circulation: Cardiovascular Interventions. 2022;15(12):e012183.

13. Ward RC, McGill T, Adel F, Ponamgi S, Asirvatham SJ, Baddour LM, et al. Infection rate and outcomes of Watchman devices: results from a single-center 14-year experience. Biomedicine Hub. 2021;6(2):59–62.

14. Sener YZ, Ozer SF, Karahan G. A current perspective on left atrial appendage closure device infections: a systematic review. Pacing and Clinical Electrophysiology. 2025 May;48(5):492–9.

15. Galea R, Bini T, Perich Krsnik J, Touray M, Gil Temperli F, Kassar M, et al. Pericardial effusion after left atrial appendage closure: timing, predictors, and clinical impact. JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions. 2024;17(11):1295–307.

16. Price MJ, Valderrábano M, Zimmerman S, Friedman DJ, Kar S, Curtis JP, et al. Periprocedural pericardial effusion complicating transcatheter left atrial appendage occlusion: a report from the NCDR LAAO Registry. Circulation: Cardiovascular Interventions. 2022;15(5):e011718.

17. Wang B, Wang Z, Chu H, He B, Fu G, Feng M, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of left atrial appendage closure in patients with small appendage orifices measured with transesophageal echocardiography. Clinical Cardiology. 2023;46(2):134–41.

18. Spencer RJ, DeJong P, Fahmy P, Lempereur M, Tsang MYC, Gin KG, et al. Changes in left atrial appendage dimensions following volume loading during percutaneous left atrial appendage closure. JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions. 2015;8(15):1935–41.

19. Freitas-Ferraz AB, Bernier M, O’Connor K, Beaudoin J, Champagne J, Paradis JM, et al. Safety and effects of volume loading during transesophageal echocardiography in the pre-procedural work-up for left atrial appendage closure. Cardiovascular Ultrasound. 2021;19(1):3.

20. Nielsen-Kudsk JE, Berti S, Caprioglio F, Ronco F, Arzamendi D, Betts T, et al. Intracardiac echocardiography to guide Watchman FLX implantation: the ICE LAA study. JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions. 2023;16(6):643–51.

21. Alkhouli M, Du C, Killu A, Simard T, Noseworthy PA, Friedman PA, et al. Clinical impact of residual leaks following left atrial appendage occlusion: insights from the NCDR LAAO Registry. JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology. 2022;8(6):766–78.