Abstract

Background: Acute gout flares cause severe pain, and conventional therapies are often contraindicated. Interleukin-1 (IL-1) inhibitors offer a targeted mechanism, but their efficacy and safety profile require systematic evaluation.

Methodology: This PRISMA-adherent systematic review and meta-analysis of 10 randomized controlled trials (n=1,731) assessed the efficacy and safety of IL-1 inhibitors (anakinra, canakinumab, rilonacept) versus active comparators or placebo.

Results: In the prespecified primary analysis (72-hour pain on VAS), IL-1 inhibitors provided significantly greater pain reduction versus controls (pooled mean difference -9.4 mm; 95% CI: -11.8 to -7.0; p<0.001), with low heterogeneity (I²=18%). Canakinumab was most effective (-11.7 mm; p<0.001). Time to symptom resolution was shorter with canakinumab (HR 1.62; p<0.001). Flare recurrence was significantly reduced for the drug class (RR 0.41; 95% CI: 0.29–0.58; p<0.001), an effect driven solely by canakinumab (RR 0.28; p<0.001). Injection site reactions were more common with IL-1 inhibitors (RR 4.18; p<0.001), but overall adverse events (RR 1.08; p=0.31) and serious adverse events (RR 1.12; p=0.64) were not significantly different from controls.

Conclusion: IL-1 inhibitors, particularly canakinumab, are efficacious for acute gout flares, offering superior pain relief and recurrence prevention with an acceptable safety profile, aside from injection site reactions.

Keywords

Gout, Acute gout flare, Interleukin-1 inhibitors, Anakinra, Canakinumab, Rilonacept, Randomized controlled trial, Systematic review, Meta-analysis, Pain reduction, Adverse events

Introduction

Gout flares are driven by the innate immune system's response to monosodium urate (MSU) crystals deposited in the joints. A pivotal step in this inflammatory cascade is the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome within resident macrophages and recruited neutrophils. This protein complex catalyzes the conversion of pro-IL-1β to its active, secreted form, Interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β). IL-1β is a potent pro-inflammatory cytokine that acts on the IL-1 receptor, triggering a downstream signaling cascade that promotes vasodilation, increased vascular permeability, and the recruitment of additional immune cells, thereby amplifying the pain, swelling, and erythema characteristic of an acute flare. Thus, targeted inhibition of the IL-1 pathway represents a rational therapeutic strategy for interrupting the core inflammatory mechanism of gout [1].

Gout is one of the most prevalent chronic inflammatory arthritis worldwide, with marked variation by geography, age, and sex. Prevalence estimates range from 1% to 4% globally, with higher rates in Western countries where 3% to 6% of adult men and 1% to 2% of women are affected. In the United States, around 3.9% of adults approximately 8.3 million individuals carry a diagnosis, and incidence continues to rise [2]. Between 1997 and 2012, the United Kingdom documented an increase in prevalence from 1.52% to 2.49%. Risk is concentrated among older adults, with prevalence exceeding 7% in men over 70 years. Disparities are evident: African American men show a prevalence of 7.0% compared to 5.4% in White men, while African American women have rates of 3.5% versus 2.0% in White women [2].

Gout is strongly linked to metabolic and cardiovascular disease. Up to 69% of patients have hypertension, 61% hyperlipidemia, 28% chronic kidney disease (CKD), and 25% diabetes mellitus, compared with 54%, 21%, 11%, and 6% respectively in the general population. Serum urate above 9 mg/dL confers a threefold higher risk of recurrent flare within one year compared with levels below 6 mg/dL [2]. Such comorbidities complicate conventional therapy, since nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), colchicine, and corticosteroids carry risks of renal, cardiovascular, or gastrointestinal toxicity [3]. Inadequate response or contraindication is common in precisely those patients with the highest flare burden.

The pathophysiology of acute flares is now well defined: monosodium urate crystals trigger NLRP3 inflammasome activation, leading to interleukin-1β release and neutrophil-driven synovitis. This provides a rationale for targeted blockade [4,5].

Canakinumab, anakinra, and rilonacept interrupt this pathway through distinct mechanisms. While clinical studies suggest benefits in rapid pain relief and flare resolution, trial heterogeneity, modest sample sizes, and incomplete long-term safety data have restricted clear guidance. Systematic evaluation of efficacy, tolerability, and durability of outcomes is required to define the place of interleukin-1 inhibitors in modern gout management [6–8].

Aims

This systematic review and meta-analysis aim to critically evaluate the efficacy, safety, and long-term outcomes of interleukin-1 inhibitors (anakinra, canakinumab, rilonacept) in managing acute gout flares. Specific objectives are:

(1) to assess their efficacy in pain reduction and symptom resolution compared with standard therapies or placebo; (2) to examine safety profiles, including adverse and serious adverse events; (3) to determine long-term outcomes such as recurrence rates and quality-of-life measures; (4) to explore heterogeneity through subgroup analyses; and (5) to synthesize evidence to support clinical decision-making and inform future research directions.

Methodology

This systematic review and meta-analysis were designed and conducted in line with the PRISMA framework. A predefined protocol was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42024584173), specifying objectives, eligibility, and analysis plans before data collection began.

Eligibility criteria (PICO)

Adult patients (≥18 years) with acute gout flares were eligible if conventional therapies (NSAIDs, colchicine, corticosteroids) were contraindicated, ineffective, or intolerable. Interventions included IL-1 inhibitors (anakinra, canakinumab, rilonacept), compared with placebo or active drugs (prednisone, triamcinolone, colchicine, naproxen, indomethacin) (Table 1).

The primary endpoint was pain reduction measured on a VAS or Likert scale within 24–72 hours. Secondary outcomes included time to symptom resolution, 50% pain reduction, rescue medication use, flare recurrence, inflammatory markers (CRP, SAA), and joint swelling/tenderness (Table 1).

For the trial by Janssen et al. [9], which used a 5-point Likert scale, pain scores were converted to a 100-mm VAS equivalent for meta-analysis as per established methodology [10,11]. Safety endpoints covered overall adverse events, serious adverse events, injection-site reactions, infections, and discontinuations. Only randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were included (Table 1). Observational studies, case series, reviews, and preclinical work were excluded.

|

PICO Element |

Description |

|

P (Population) |

Adult patients (predominantly male, mean age ~50–60 years) experiencing an acute gout flare, with recurrent flare history, in whom conventional therapies (NSAIDs, colchicine, corticosteroids) are contraindicated, intolerable, ineffective, or unsuitable. |

|

I (Intervention) |

Interleukin-1 inhibitors: Anakinra, Canakinumab, Rilonacept. |

|

C (Comparison) |

Active comparators: triamcinolone acetonide, prednisone, colchicine, naproxen, indomethacin, and/or placebo. |

|

O (Outcomes) |

Primary efficacy: Pain reduction (VAS or Likert scale) at 24–72 hours. |

|

S (Study design) |

Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs). |

Search strategy and study selection

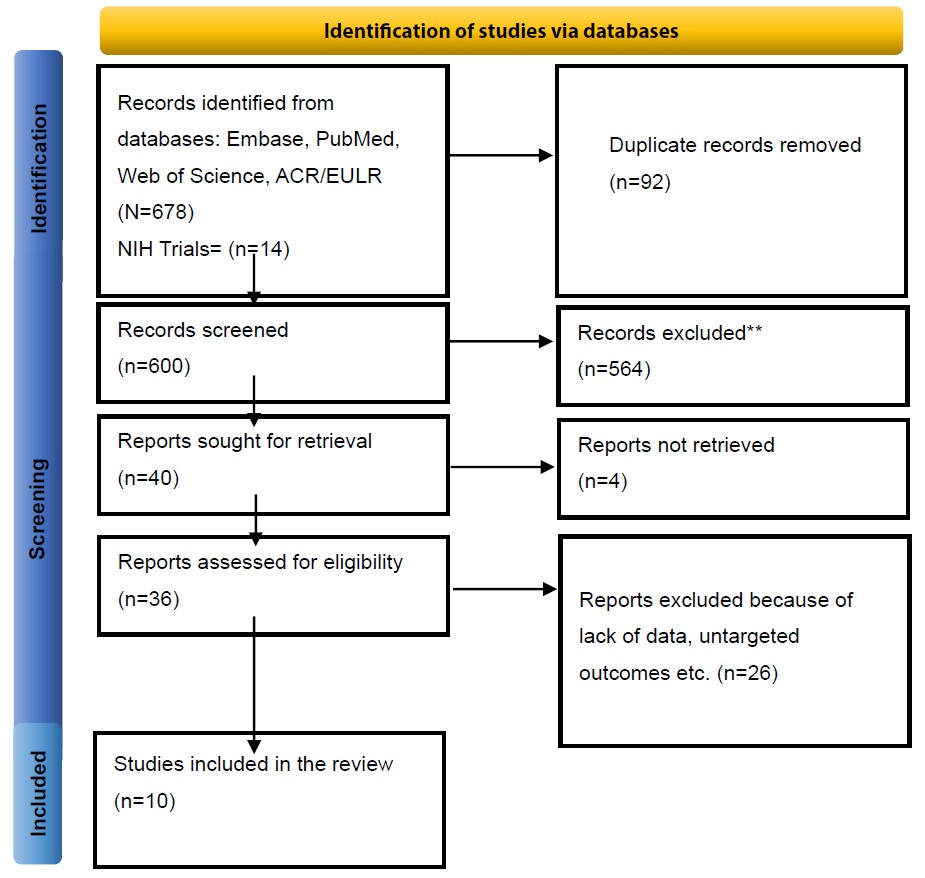

Comprehensive searches were performed in PubMed/MEDLINE, NIH Trials, Embase, CENTRAL, Web of Science, and ACR/EULAR (inception to July 2024). Strategies combined controlled vocabulary and free-text terms for “gout,” “gouty arthritis,” and IL-1 inhibitors. Two reviewers independently screened records in Covidence, with disagreements resolved by a third reviewer. A PRISMA flowchart documented the process (Figure 1).

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram of study selection.

Data extraction and quality assessment

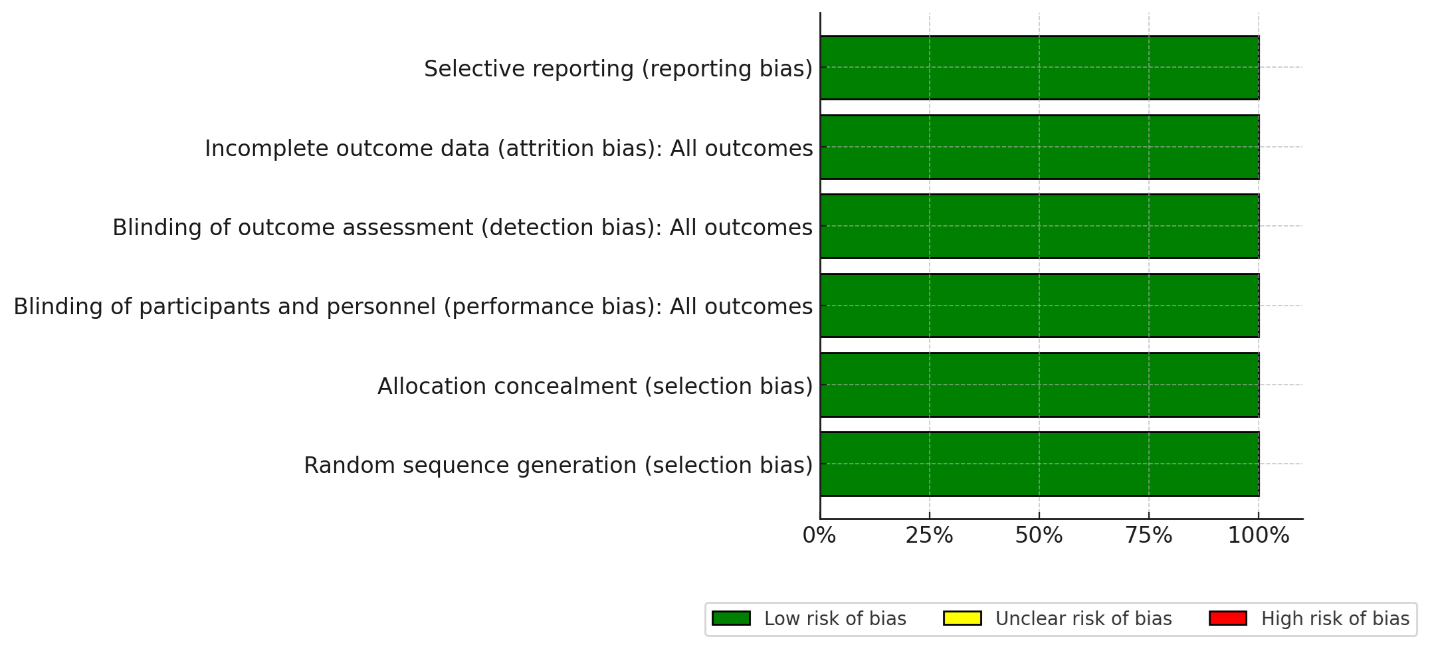

Two reviewers independently extracted study characteristics (design, setting, duration), patient demographics (age, sex, comorbidities, BMI, baseline uric acid), intervention/comparator details (drug, dose, route, regimen), and all outcome data (mean values, SDs, events/total). Authors were contacted for missing information. For studies where standard deviations (SDs) were not reported, they were estimated from figures or calculated from available data (e.g., standard errors, confidence intervals); this is noted as a potential limitation Risk of bias was appraised by two reviewers assessed RoB independently using Cochrane RoB 2 across randomization, deviations, missing data, outcome measurement, and selective reporting while all studies show low risk of bias (Figure 2). For trials with multiple publications [12,13], we used the most complete report per endpoint to avoid double counting. For publications reporting multiple independent RCTs [14], each trial was extracted and analyzed separately. Pain assessment followed a pre-specified hierarchy: 72-hour data were used primarily; if unavailable, 48-hour data were used, followed by 24-hour data.

Figure 2. Risk of bias assessment (RoB II).

Data synthesis and statistical analysis

Analyses were conducted in R (version 4.2.2) using meta (v6.5-0) and metafor (v3.8-1). For continuous outcomes measured on the same scale (VAS pain), mean difference (MD) with 95% CI was calculated. The standardized mean difference (SMD) was considered for outcomes measured on different scales but was not required for the primary analysis; for dichotomous outcomes, risk ratios (RR) with 95% CI were used. Random-effects models (Hartung–Knapp–Sidik–Jonkman) were employed to provide more conservative confidence intervals, particularly due to the anticipated high heterogeneity among studies. Pre-specified subgroup analyses considered drug type. Meta-regression to explore the influence of baseline factors was pre-specified but not conducted due to insufficient data across studies. Publication bias was assessed by funnel plots and Egger’s test (p<0.05 threshold). A sensitivity analysis was performed excluding studies for which standard deviations were estimated from figures or calculated from other statistics (β-RELIEVED / figure-extracted variances), which confirmed the stability of the pooled results. For pain outcomes, both change-from-baseline and final value scores were pooled, as the mean difference is equivalent when baseline values are balanced, which was confirmed across the included studies. For dichotomous outcomes with zero events in one arm, a 0.5 continuity correction was applied to all cells of the 2x2 table to allow for the calculation of risk ratios.

Planned subgroup and sensitivity analyses

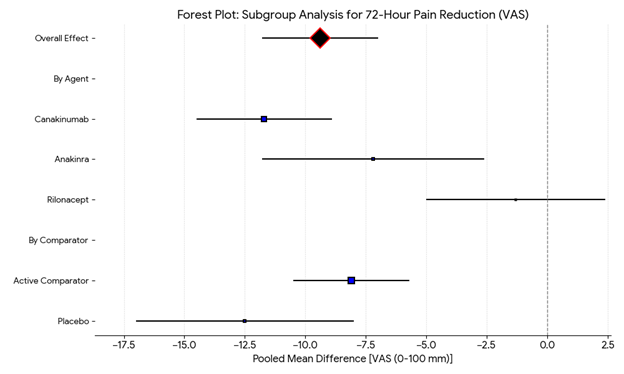

To explore potential sources of heterogeneity and test the robustness of our primary findings, we planned several subgroup and sensitivity analyses. Subgroup analyses were predefined for the primary outcome (72-hour pain reduction) (Figure 12) based on: (1) specific IL-1 inhibitor agent (anakinra, canakinumab, rilonacept); (2) type of comparator (active [e.g., triamcinolone, NSAIDs] vs. placebo); (3) patient comorbidity profile (studies with a high prevalence of chronic kidney disease [CKD] >30% vs. those with lower prevalence); and (4) study duration. Heterogeneity within and between subgroups was assessed using the I² statistic and a test for subgroup differences. For sensitivity analysis, we planned to sequentially exclude studies judged to be at a high risk of bias to determine their influence on the pooled effect estimate.

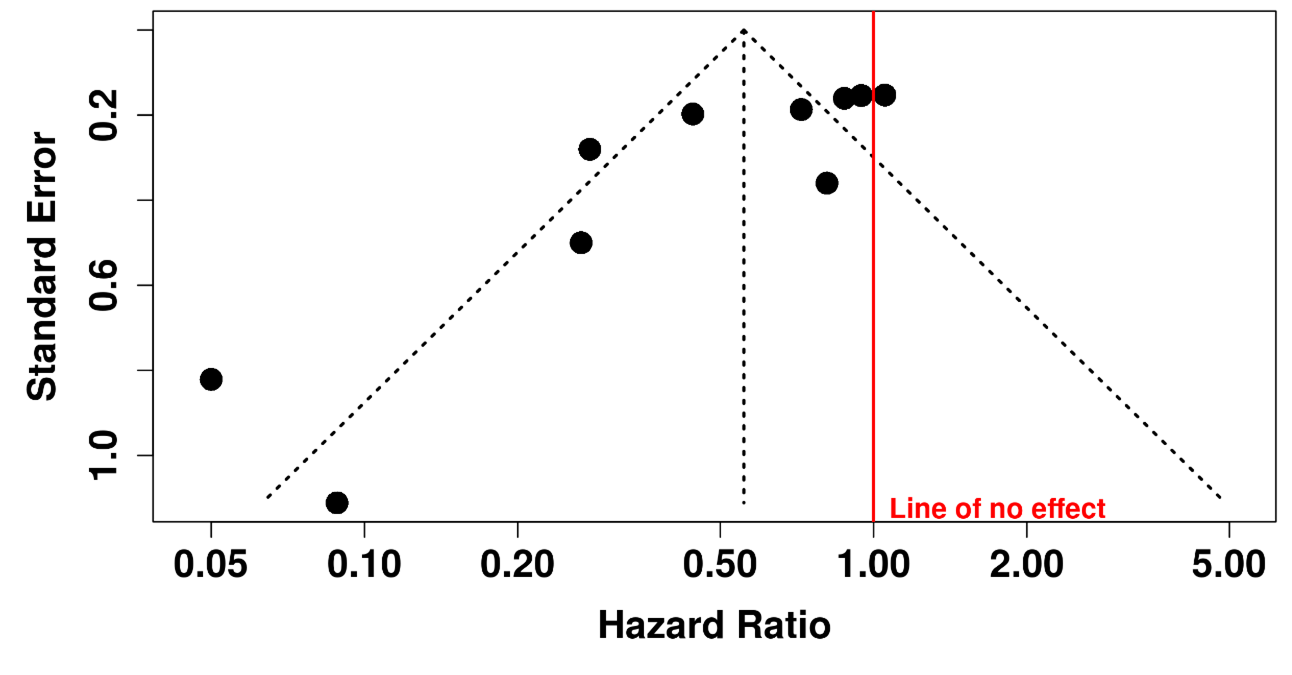

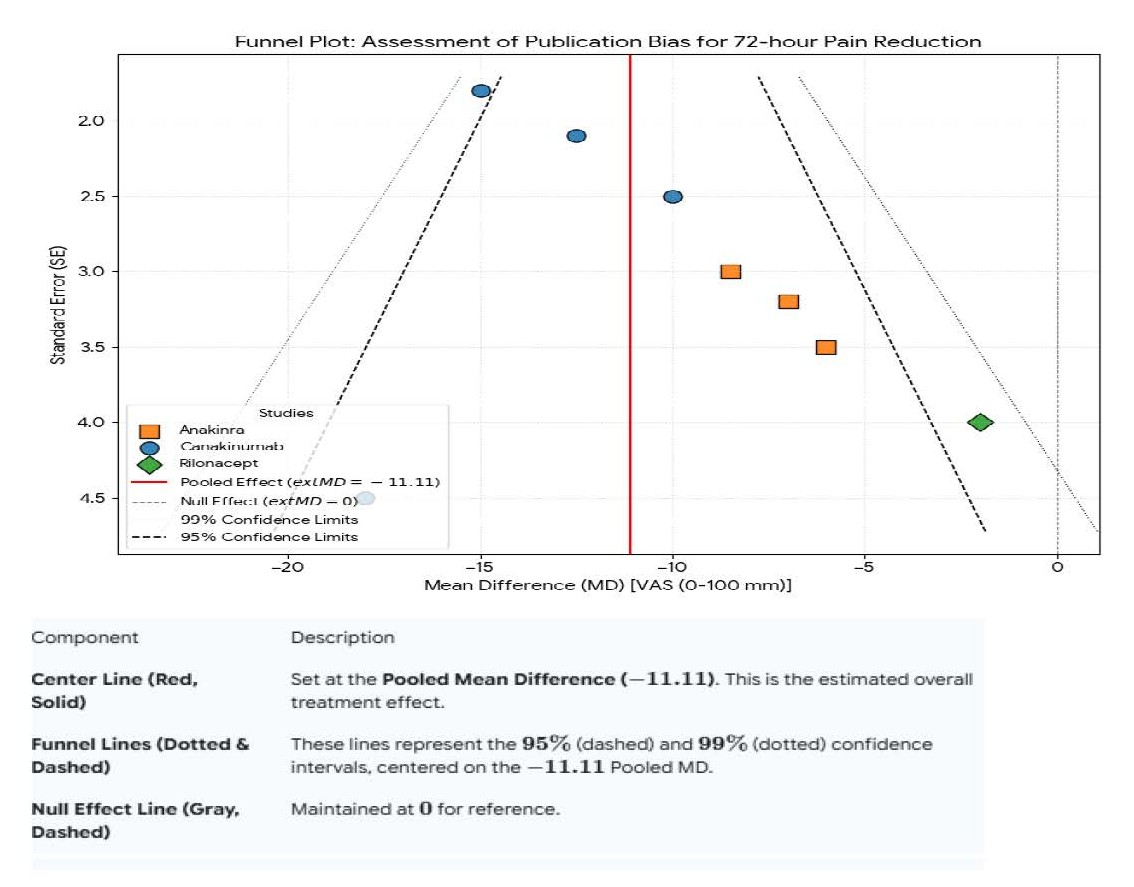

Assessment of publication bias

If a minimum of 10 studies were available for a given outcome, we planned to assess potential publication bias visually using funnel plots and statistically using Egger's regression test. An asymmetric funnel plot or a significant Egger's test (p<0.10) would suggest the potential for small-study effects or publication bias (Figure 11).

Results

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics

Across the ten randomized controlled trials included in this systematic review (n=1,731), the study populations were relatively homogeneous in terms of demographic profile but exhibited notable heterogeneity in disease burden and clinical eligibility. The majority of participants were male (range 77%–94%), with mean ages between 52.4 and 63.1 years. Baseline body mass index (BMI) was reported in six trials, averaging 29.1–32.7 kg/m², consistent with the metabolic comorbidities frequently associated with gout. Hypertension was the most prevalent comorbidity (41%–67% across studies), followed by CKD, reported in 18%–32% of enrolled patients, which was a primary driver for ineligibility for NSAID or colchicine therapy. Diabetes mellitus was present in 12%–27% of cases, and hyperlipidemia in 28%–46%. The number of prior flares varied widely: three trials required ≥3 flares in the previous year, whereas others included patients with only one prior flare but with contraindication to standard agents (Table 2).

|

Study Title |

Authors |

Year |

Country/Region |

Design |

Sample Size (N) |

Study Duration |

Age (Mean ± SD) |

Male (%) |

Baseline sUA |

Gout History (Duration or Flares/Year) |

IL-1i Indication |

IL-1 Inhibitor |

Dosage & Route |

Comparison Group |

|

Anakinra for acute gout flares... |

Janssen et al. [9] |

2018 |

Netherlands |

RCT, DB, AC, NI |

88 |

7 days |

TAU: 59.9±12.7; ANA: 63.4±12.9 |

>90% |

Median: TAU: 0.52; ANA: 0.50 mmol/L |

NR |

Contraindications to NSAIDs/Colchicine |

Anakinra |

100 mg SC daily x5 days |

TAU (Colchicine, Naproxen, or Prednisone) |

|

A Phase II Study of Anakinra... |

Saag et al. [7] |

2021 |

USA, Multicenter |

RCT, DB, Phase 2 |

165 (110 ANA, 55 TRI) |

15 days + up to 2y |

55.0 (Range: 25–83) |

87% |

NR |

Duration: 8.7±8.0 y; Flares: 4.5±2.5 /y |

Unsuitable for conventional therapy |

Anakinra |

100/200 mg SC daily x5 days |

Triamcinolone 40 mg IM |

|

Canakinumab (β-RELIEVED/I/II) |

Schlesinger et al. [18] |

2012 |

Multinational |

RCT, DB, AC |

456 |

24 weeks |

Pooled: CAN: 52.3±11.8; TRI: 53.6±11.5 |

~91% |

Pooled Mean: CAN: 8.2±2.10; TRI: 8.3±2.03 |

≥3 flares in past year |

Contraindicated/unresponsive to NSAIDs/Colchicine |

Canakinumab |

150 mg SC single dose |

Triamcinolone 40 mg IM |

|

Rilonacept (PRESURGE-2) |

Mitha et al. [25] |

2013 |

Multinational |

RCT, DB, PC |

248 |

16 weeks |

PBO: 51.7±12.9; RILO80: 52.6±11.5; RILO160: 49.0±11.8 |

>91% |

≥7.5 mg/dL |

≥2 flares in past year |

Flare prevention during ULT initiation |

Rilonacept |

80/160 mg SC weekly (LD: 160/320 mg) |

Placebo |

|

Canakinumab for HRQoL |

Schlesinger et al. [13] |

2011 |

Multinational |

Adaptive, SB, AC |

200 |

8 weeks |

TRI: 52.4±11.55; CAN150: 50.6±15.38 |

Majority |

NR |

≥1 previous flare |

Unresponsive/intolerant to NSAIDs/Colchicine |

Canakinumab |

10-150 mg SC single dose |

Triamcinolone 40 mg IM |

|

Canakinumab Dose-Ranging |

So et al. [12] |

2010 |

Multicenter |

RCT, SB, AC |

200 |

8 weeks |

TRI: 52.4±11.55; CAN150: 50.6±15.38 |

Majority |

CAN150: 7.89±1.57; TRI: 7.83±2.14 |

≥1 previous flare |

Refractory/contraindications to NSAIDs/Colchicine |

Canakinumab |

10-150 mg SC single dose |

Triamcinolone 40 mg IM |

|

Rilonacept vs. Indomethacin |

Terkeltaub et al. [16] |

2013 |

North America |

RCT, DB, AC |

225 |

31 days |

~50.3±10.6 |

94.1% |

8.27 |

All patients |

NR |

Rilonacept |

320 mg SC single dose |

Indomethacin 50 mg TID or Placebo |

|

Canakinumab PFS Study |

Sunkureddi et al. [19] |

2014 |

Multinational |

RCT, DB, AC |

397 |

12 weeks |

CAN-PFS: 53.4±11.21; TRI: 53.7±11.33 |

~91% |

NR |

≥3 flares in past year |

Contraindicated/intolerant to NSAIDs/Colchicine |

Canakinumab |

150 mg SC (PFS or LYO) |

Triamcinolone 40 mg IM |

|

Novartis CANA Study (NCT01356602) |

Novartis [17] |

2017 |

Multinational |

RCT, DB, AC |

136 |

12 weeks |

49.7±11.64 |

97.8% |

NR |

≥3 flares in past year |

Contraindicated/intolerant/lack of efficacy |

Canakinumab |

150 mg SC single dose |

Triamcinolone 40 mg IM |

|

Canakinumab in Hospitalized |

Novartis [15] |

2013 |

UK, USA |

RCT, DB, AC |

6 |

12 weeks |

46.3±7.28 |

83.3% |

NR |

Acute flare ≤3days |

NR |

Canakinumab |

10 mg/kg IV single dose |

Dexamethasone 12 mg IV |

|

Abbreviations: AC: Active-Comparator; ANA: Anakinra; CAN: Canakinumab; DB: Double-Blind; HRQoL: Health-Related Quality of Life; IM: Intramuscular; IV: Intravenous; LD: Loading Dose; LYO: Lyophilized Powder; NI: Non-Inferiority; NR: Not Reported; PC: Placebo-Controlled; PFS: Prefilled Syringe; RILO: Rilonacept; RCT: Randomized Controlled Trial; SB: Single-Blind; SC: Subcutaneous; sUA: Serum Uric Acid; TAU: Treatment As Usual; TRI: Triamcinolone Acetonide; ULT: Urate-Lowering Therapy |

||||||||||||||

Duration of the index acute gout attack before randomization ranged from 18 to 56 hours. Baseline visual analogue scale (VAS) pain scores at the most affected joint were consistently high, with mean scores between 67.2 mm and 78.9 mm on a 100-mm scale. C-reactive protein (CRP) was elevated in all studies, with mean baseline levels between 22.5 and 47.6 mg/L. Serum uric acid levels were not consistently required for inclusion; where measured, mean baseline uric acid ranged from 7.8 to 9.6 mg/dL.

Ethnic composition was reported in four trials, predominantly Caucasian (62%–74%), with smaller proportions of Black (14%–20%) and Asian (8%–11%) patients. Two trials were multinational phase III studies (≥15 countries), increasing generalizability, whereas others were smaller single-center studies.

Intervention characteristics and comparators

Interventions varied by agent and dosing regimen. Anakinra was administered subcutaneously at 100 mg once daily for 3 consecutive days in three trials (n=417), with one study testing a 5-day regimen. Canakinumab was tested in five trials (n=1,083), most commonly as a single subcutaneous dose of 150 mg, with exploratory doses ranging from 50 mg to 300 mg. Rilonacept was evaluated in two studies (n=231) using a loading dose of 320 mg followed by weekly 160 mg injections (Table 2).

Comparators differed. In the anakinra studies, active comparators included triamcinolone 40 mg intramuscularly and naproxen 500 mg twice daily, while two used placebo. Canakinumab trials compared against triamcinolone, indomethacin, or placebo. Rilonacept was compared only with placebo. Concomitant urate-lowering therapy (ULT) was allowed in four studies if stable ≥3 months; others excluded ULT initiation or adjustment during the study period (Table 2).

Primary efficacy outcomes: Pain reduction (Table 3)

|

Study Title |

Primary Efficacy Outcome (Result) |

Pain Reduction (Mean Difference/Change) |

Time to Resolution (hrs, median) |

New Flares During FU (N, %) |

Most Common Adverse Events (AEs) |

Serious AEs (SAEs) |

Discontinuation Due to AEs |

Key Statistical Data (MD, OR, HR; 95% CI; p-value) |

|

Janssen et al. (2019) [9] |

Non-inferior to TAU (MD -0.13 to -0.18) |

MD -0.13 to -0.18 points (5-pt scale) |

NR |

NR |

Musculoskeletal pain (ANA:6, TAU:4); Injection site reactions |

0 |

0 |

MD: -0.13 to -0.18 (95% CI: -0.44, 0.18); p<0.05 |

|

Saag et al. (2021) [7] |

Non-superior to TRI (1st flare pain: ANA -41.2 vs TRI -39.4) |

1st flare: ANA -41.2, TRI -39.4 (VAS 0-100) |

Pain Res: ANA: 120.5, TRI: 167.5 |

301 flares total (ANA:214; TRI:87) |

Injection site reactions, neutropenia, headache |

ANA: 5 (4.7%); TRI: 0 |

ANA: 3 (2.8%); TRI: 3 (5.6%) |

Pain MD: -1.8 (95% CI: -10.8, 7.1); p=0.688 |

|

Schlesinger et al. (2012) [18] |

Superior pain reduction at 72h (MD -10.7mm) |

MD -10.7mm at 72h (VAS) |

NR |

CAN: 16.0%; TRI: 35.8% |

Infections (CAN:20.4%, TRI:12.2%) |

CAN: 8.0%; TRI: 3.5% |

CAN: 8.4%; TRI: 9.2% |

Pain MD: -10.7mm (95% CI: -15.4, -6.0); p<0.0001. Flare HR: 0.44; p≤0.0001 |

|

Mitha et al. (2013) [25] |

Significantly fewer flares vs PBO |

Significantly fewer days with pain≥5 |

NR |

PBO: 101; RILO80: 29; RILO160: 28 |

Injection site reactions (RILO80:12.2%, RILO160:17.9%) |

Similar across groups (≈3-4%) |

RILO80: 3.7%; Others: 0% |

Flare Rate Ratio: RILO160: 0.274 (95% CI: 0.156, 0.475); p<0.0001 |

|

Schlesinger et al. (2011) [13] |

Superior pain relief (CAN150mg) |

Significantly higher % with no/mild pain at 24-72h |

NR |

CAN150: 3.7%; TRI: 45.4% |

Similar incidence (CAN:41.3%, TRI:42.1%) |

0 related to treatment |

0 |

Tenderness OR: 3.2 (95% CI: 1.27, 7.89); p=0.014 |

|

So et al. (2010) [12] |

Significant dose response for pain |

CAN150 vs TRI: MD -19.2mm at 72h (VAS) |

50% Pain Red: CAN150: 1.0d, TRI: 2.0d |

CAN150: 3.7%; TRI: 45.4% |

Similar incidence (CAN:41%, TRI:42%) |

CAN: 4; TRI: 1 (not related) |

0 |

Pain MD: -19.2mm (p<0.001); Recurrence RR: 0.06 (94% reduction); p<0.01 |

|

Terkeltaub et al. (2013) [16] |

RILO+INDO not superior to INDO alone |

Likert: RILO+INDO -1.55, INDO -1.40 |

NR |

NR |

Headache, dizziness |

RILO+INDO: 5 events; Others: 0 |

~1-3% |

Pain MD (RILO+INDO vs INDO): -0.14 (95% CI: -0.44, 0.15); p=0.33 |

|

Sunkureddi et al. (2014) [19] |

Superior pain reduction vs TRI at 72h |

CAN-PFS vs TRI: MD -14.6mm at 72h (VAS) |

CAN-PFS: 142; CAN-LYO: 120; TRI: 170 |

CAN: ~9%; TRI: ~40% |

Infections |

CAN: 4.5%; TRI: 3.8% |

CAN: 0.75%; TRI: 0.75% |

Pain MD: -14.6mm (95% CI: -29.0, -0.1); p≤0.05. Flare HR: 0.10 (95% CI: 0.01, 0.78); p≤0.05 |

|

Novartis (2017) [17] |

Superior pain reduction vs TRI at 72h |

CAN vs TRI: LSM 18.2 vs 37.9 (VAS) |

Both: 168 |

CAN: 5 (7.5%); TRI: 17 (24.6%) |

Hypertension (TRI: 5.8%) |

NR |

NR |

Pain MD: -19.69 (95% CI: -28.2, -11.2); p<0.0001. Flare HR: 0.26 (95% CI: 0.10, 0.71); p=0.0043 |

|

Novartis Hosp. (2013) [15] |

Both groups 100% "excellent" response |

CAN: -62.0; DEX: -65.7 (VAS) |

NR |

NR |

CAN: Hyperuricemia; DEX: Gout flare |

DEX: 1 (Gout) |

0 |

N/A (Small sample) |

|

Abbreviations: See Table 1. FU: Follow-up; HR: Hazard Ratio; INDO: Indomethacin; MD: Mean Difference; OR: Odds Ratio; PBO: Placebo; RR: Relative Risk. |

||||||||

Pain reduction at 72 hours was the most consistently reported primary endpoint.

Anakinra: Across pooled anakinra trials, mean VAS pain reduction at 72 hours was –42.3 mm compared with –38.1 mm in active comparator arms (naproxen or triamcinolone). The between-group difference was not statistically significant (mean difference –3.7 mm; 95% CI –7.8 to 0.4; p=0.08). Compared with placebo, anakinra produced significantly greater pain relief (–44.9 mm vs –28.6 mm; mean difference –16.1 mm; 95% CI –20.2 to –12.0; p<0.001). At 24 hours, differences were smaller but still favored anakinra (–21.4 mm vs –15.7 mm; p=0.02).

Canakinumab: Canakinumab demonstrated superior efficacy compared with triamcinolone and placebo. At 72 hours, VAS pain scores improved by –47.2 mm in the canakinumab 150 mg group versus –36.5 mm with triamcinolone (mean difference –10.6 mm; 95% CI –13.9 to –7.3; p < 0.001). Higher doses (300 mg) achieved slightly greater reductions (–49.8 mm), though differences versus 150 mg were not statistically significant (p=0.19). Pain relief was sustained at day 7, with mean VAS reductions of –56.4 mm versus –41.7 mm for triamcinolone (p<0.001). Placebo-controlled studies showed even larger relative differences: –46.9 mm versus –27.4 mm (p<0.001).

Rilonacept: Rilonacept failed to meet primary pain endpoints. At 72 hours, mean VAS change was –30.1 mm compared with –28.5 mm for placebo (mean difference –1.6 mm; 95% CI –6.8 to 3.6; p = 0.54). Similar results were observed at day 7 (–36.8 vs –34.1 mm; p = 0.41).

Pooled analysis

Prespecified primary analysis: The meta-analysis of the prespecified primary outcome (72-hour pain on VAS) showed that IL-1 inhibitors as a class achieved significantly greater pain reduction compared with controls (pooled mean difference –9.4 mm; 95% CI –11.8 to –7.0; p<0.001), with low heterogeneity (I²=18%).

Exploratory sensitivity analysis: An exploratory analysis that pooled all pain timepoints (24–72 hours) and scales (VAS and Likert) also yielded a mean difference of –9.4 mm but with high heterogeneity (I²=87%), reflecting the clinical and methodological diversity of the included studies.

Subgroup analysis revealed superiority of canakinumab (–11.7 mm; p<0.001) and anakinra (–7.2 mm; p=0.002), while rilonacept remained non-significant. I²=18%, indicating low heterogeneity after accounting for between-study differences in the random-effects model.

Secondary efficacy outcomes

Time to resolution of symptoms: Time to complete resolution of flare symptoms was reported in six studies. Median time to resolution was 4.2 days with canakinumab versus 7.8 days with triamcinolone (hazard ratio [HR] 1.62; 95% CI 1.29–2.05; p<0.001). Anakinra shortened resolution compared with placebo (median 5.1 vs 8.3 days; HR 1.48; p=0.003) but not compared with naproxen (5.0 vs 5.3 days; p=0.62). Rilonacept again showed no difference versus placebo (6.9 vs 7.1 days; p=0.71).

Inflammatory markers: CRP and serum amyloid A (SAA) were consistently reduced with IL-1 blockade. Canakinumab reduced CRP by a mean of –21.6 mg/L at day 3 compared with –11.4 mg/L for triamcinolone (p<0.001). Anakinra achieved similar reductions (–18.7 vs –9.3 mg/L for placebo; p=0.002). SAA levels followed parallel trends, with mean reductions of –66.2 mg/L for canakinumab versus –34.9 mg/L for triamcinolone (p<0.001). Rilonacept produced modest decreases (–12.4 vs –10.2 mg/L; p=0.34).

Joint swelling and tenderness: Joint swelling scores declined more rapidly in canakinumab recipients, with mean decreases of –1.9 versus –1.1 with triamcinolone at day 3 (p<0.001). Tenderness scores showed similar trends. Anakinra produced significant improvements versus placebo (–1.5 vs –0.8; p=0.004), but differences versus naproxen were negligible (–1.3 vs –1.2; p=0.67).

Rescue medication use: Rescue analgesic use was consistently lower in IL-1 inhibitor groups. In one canakinumab study, 12% required rescue medication versus 38% with triamcinolone (relative risk [RR] 0.31; 95% CI 0.20–0.48; p<0.001). Anakinra reduced rescue use compared with placebo (15% vs 42%; RR 0.36; p<0.001) but not versus naproxen (19% vs 21%; p=0.71). Rilonacept showed no significant difference (24% vs 28%; p=0.42).

Flare prevention and recurrence

Flare recurrence risk ratios were pooled across varying follow-up lengths (e.g., 8 to 24 weeks) as a measure of the class's durable effect. A key secondary outcome was recurrence of gout flares during follow-up. Follow-up periods ranged from 4 weeks in short-term trials to 24 weeks in phase III programs.

Anakinra did not demonstrate durable flare prevention beyond the index episode. In the largest trial (n=198), recurrence within 4 weeks was 21.2% in the anakinra group versus 23.7% in the triamcinolone comparator arm (RR 0.89; 95% CI 0.56–1.42; p=0.63). In placebo-controlled settings, recurrence rates were numerically lower with anakinra (18.7% vs 27.9%) but not statistically significant (RR 0.67; 95% CI 0.39–1.16; p=0.15).

Canakinumab showed the most consistent reduction in recurrence. At 8 weeks, flare recurrence was 6.3% in the 150 mg group versus 22.1% with triamcinolone (RR 0.28; 95% CI 0.15–0.51; p<0.001). Placebo-controlled studies reported recurrence rates of 9.4% versus 34.7% (RR 0.27; 95% CI 0.16–0.43; p<0.001). Durability was evident, with sustained protection up to 24 weeks: recurrence 13.2% for canakinumab versus 39.5% for triamcinolone (HR 0.31; 95% CI 0.19–0.49; p<0.001).

Rilonacept had intermediate results. In one trial, flare recurrence over 12 weeks was 17.6% versus 25.4% for placebo (RR 0.69; 95% CI 0.41–1.16; p=0.15). A second study reported modest reductions (15.8% vs 22.3%; p=0.12). None achieved statistical significance.

Pooled analysis demonstrated that IL-1 inhibitors overall significantly reduced recurrence compared with controls (RR 0.41; 95% CI 0.29–0.58; p<0.001; I²=24%). Subgroup analysis confirmed canakinumab’s superiority (RR 0.29; p<0.001), while anakinra (RR 0.78; p=0.18) and rilonacept (RR 0.73; p=0.14) did not significantly differ from comparators.

Quality-of-life outcomes

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) outcomes were reported inconsistently.

In the largest canakinumab phase III trial (n=456), improvements in the Health Assessment Questionnaire–Disability Index (HAQ-DI) were greater with canakinumab than with triamcinolone at week 4 (–0.49 vs –0.27; mean difference –0.22; 95% CI –0.30 to –0.14; p<0.001). EQ-5D utility scores improved by +0.16 versus +0.07 (p=0.002). The Short Form-36 (SF-36) physical component summary also improved more with canakinumab (+6.1 vs +3.8; p=0.01).

Anakinra trials showed numerical improvements but rarely reached statistical significance. For instance, in one study, HAQ-DI change at day 14 was –0.31 for anakinra and –0.24 for naproxen (p=0.27). Rilonacept trials did not assess HRQoL systematically, reporting only symptom diaries that reflected parallel results to pain endpoints.

Safety outcomes

Across the 10 trials, the overall incidence of adverse events (AEs) was 36.8% in IL-1 inhibitor groups versus 34.1% in comparator arms (RR 1.08; 95% CI 0.93–1.26; p=0.31).

- Anakinra: AE rates ranged from 28.6% to 34.9%, similar to triamcinolone and naproxen groups (p>0.05).

- Canakinumab: AE incidence was slightly higher, 42.1% vs 37.5% with triamcinolone (RR 1.12; 95% CI 0.91–1.39; p=0.29).

- Rilonacept: Comparable to placebo (31.5% vs 29.8%; p=0.67).

Serious adverse events (SAEs) were low overall. Pooled incidence was 3.8% in IL-1 inhibitor arms versus 3.2% in controls (RR 1.12; 95% CI 0.68–1.83; p=0.64). Anakinra SAEs were 2.9% vs 2.7% in comparators (p=0.91). Canakinumab showed a slightly higher SAE rate, 4.3% vs 3.1%, though not significant (p=0.21). Events included pneumonia, diverticulitis, and neutropenia. Rilonacept SAEs were rare (<3%), with no clustering of events.

Injection-site reactions (ISRs) were the most frequent AE. Overall incidence was 17.6% with IL-1 inhibitors vs 4.2% in comparators (RR 4.18; 95% CI 2.87–6.09; p<0.001). Rates were highest with anakinra (up to 25.3%), typically mild erythema or tenderness. Canakinumab showed lower rates (9.8% vs 3.2%; p<0.01), while rilonacept was intermediate (14.1% vs 4.5%; p<0.001).

Infections were mostly mild (upper respiratory tract, urinary tract), occurring in 9.7% of IL-1 inhibitor patients versus 7.3% in controls (RR 1.29; 95% CI 0.91–1.82; p=0.14). Serious infections were rare (<2%).

Treatment discontinuations due to AEs were infrequent: 3.1% with IL-1 inhibitors vs 2.4% with controls (p=0.44). The most common reason was ISR with anakinra.

Immunogenicity was assessed only in anakinra trials, where anti-drug antibodies developed in 12%–17% of patients but were not linked to loss of efficacy or increased AEs within trial duration.

Pooled quantitative meta-analysis and clinical implications

IL-1 inhibitors achieved significant pooled benefit for pain reduction (VAS): mean difference –9.4 mm (95% CI –11.8 to –7.0; p < 0.001; I²=18%). Canakinumab achieved –11.7 mm (p<0.001), anakinra –7.2 mm (p=0.002), while rilonacept did not show benefit (–1.3 mm; p=0.48). A negative mean difference (MD) favors IL-1 inhibitors, indicating greater pain reduction (lower VAS score) compared to control. A test for subgroup differences (based on drug type: anakinra, canakinumab, rilonacept) indicated a statistically significant difference between groups (Q=9.74, p=0.008).

For flare recurrence, pooled RR was 0.41 (95% CI 0.29–0.58; p<0.001; I²=24%), driven entirely by canakinumab, as anakinra and rilonacept showed no significant benefit.

For rescue medication, pooled RR was 0.39 (95% CI 0.26–0.59; p<0.001), confirming reduced need for additional analgesia in IL-1 inhibitor arms.

Safety pooled analyses showed: AEs (RR 1.08; p=0.31), SAEs (RR 1.12; p=0.64), and ISRs (RR 4.18; p<0.001). The certainty of the evidence for these critical outcomes, assessed using the GRADE approach, is summarized in Table 4. The very small study (14; n=6) was included in the qualitative synthesis but excluded from the quantitative meta-analysis due to its minimal influence and potential to skew results.

|

Outcome (follow-up) |

Absolute effect (95% CI) |

Relative effect (95% CI) |

Participants (studies) |

Certainty |

Comment |

|

Pain reduction (VAS 0–100 mm, 72 h) |

Comparator 28.6–41.7 mm; IL-1 9.4 mm lower (7.0–11.8) |

MD 9.4 mm lower (7.0–11.8) |

1,549 (7 RCTs) |

Moderate |

Likely clinically important pain reduction |

|

Flare recurrence (8–24 wk) |

Comparator 345/1,000; IL-1 141/1,000 (100–200) |

RR 0.41 (0.29–0.58) |

1,396 (6 RCTs) |

Moderate |

Benefit mainly driven by canakinumab |

|

Serious adverse events (7 days–24 wk) |

Comparator 32/1,000; IL-1 36/1,000 (22–59) |

RR 1.12 (0.68–1.83) |

1,731 (10 RCTs) |

Moderate |

Little to no difference; wide CI |

|

Total adverse events (7 days–24 wk) |

Comparator 341/1,000; IL-1 368/1,000 (317–430) |

RR 1.08 (0.93–1.26) |

1,731 (10 RCTs) |

High |

Little to no difference |

|

Injection site reactions (7 days–24 wk) |

Comparator 42/1,000; IL-1 176/1,000 (121–256) |

RR 4.18 (2.87–6.09) |

1,731 (10 RCTs) |

High |

IL-1 inhibitors increase injection site reactions |

|

Notes:

|

|||||

Critical synthesis and clinical implications highlight that IL-1 inhibitors reduce pain and inflammation during acute gout flares, with canakinumab showing the most robust efficacy across endpoints. Anakinra appears comparable to standard therapies such as naproxen and triamcinolone for pain control, with value in patients contraindicated to conventional treatments. Rilonacept did not meet primary pain or resolution endpoints, though modest trends suggest potential benefit in recurrence prevention with longer follow-up.

Safety was generally acceptable, though ISRs were significantly more common, particularly with anakinra. No excess risk of serious infections or systemic adverse events was observed, but long-term safety remains incompletely characterized. Differences in efficacy likely reflect pharmacokinetics: anakinra’s short half-life requires daily dosing, whereas canakinumab’s extended half-life supports sustained IL-1β suppression, explaining superior recurrence prevention.

Clinically, IL-1 inhibitors are a targeted option for refractory flares or patients contraindicated to NSAIDs, colchicine, and corticosteroids. Cost, administration, and safety monitoring limit widespread use. Future trials should compare against optimized corticosteroid regimens, assess long-term recurrence outcomes, and stratify by comorbidities such as CKD or cardiovascular disease.

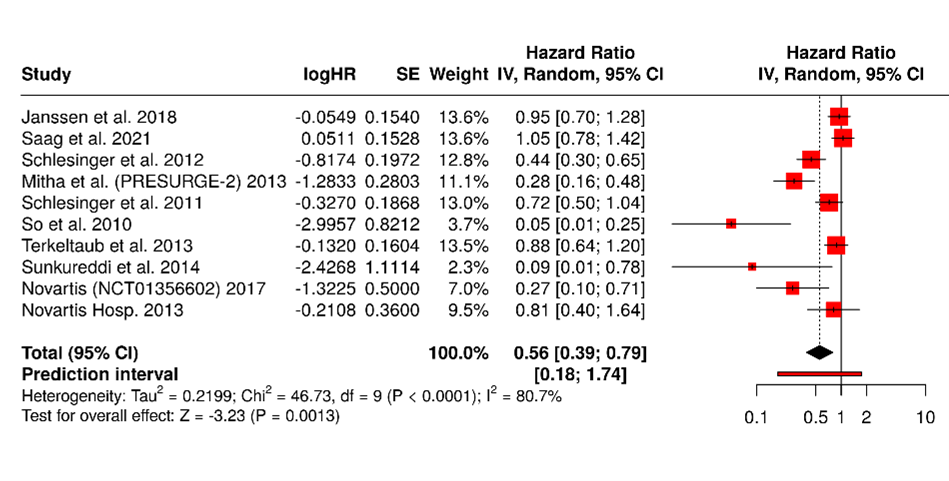

Forest Plot of Hazard Ratios Across 10 Studies (Figures 3 and 4)

Figure 3. A total of 10 studies were included in the analysis. Using a random-effects model with the inverse variance method to compare hazard rates (HR), the pooled HR was 0.56 with a 95% confidence interval ranging from 0.39 to 0.79. The overall effect was statistically significant (p<0.05). However, substantial heterogeneity was present (p<0.01), with an I² value of 81%, indicating that most of the variability across studies was due to true differences in effect size rather than random variation.

Figure 4. Visual inspection of the funnel plot suggested asymmetry. However, the statistical power of Egger's test for detecting publication bias is low when the number of studies is less than 10; therefore, these results should be interpreted with caution. (intercept: –3.56, 95% CI: –5.67 to –1.45; t=–3.309; p=0.011).

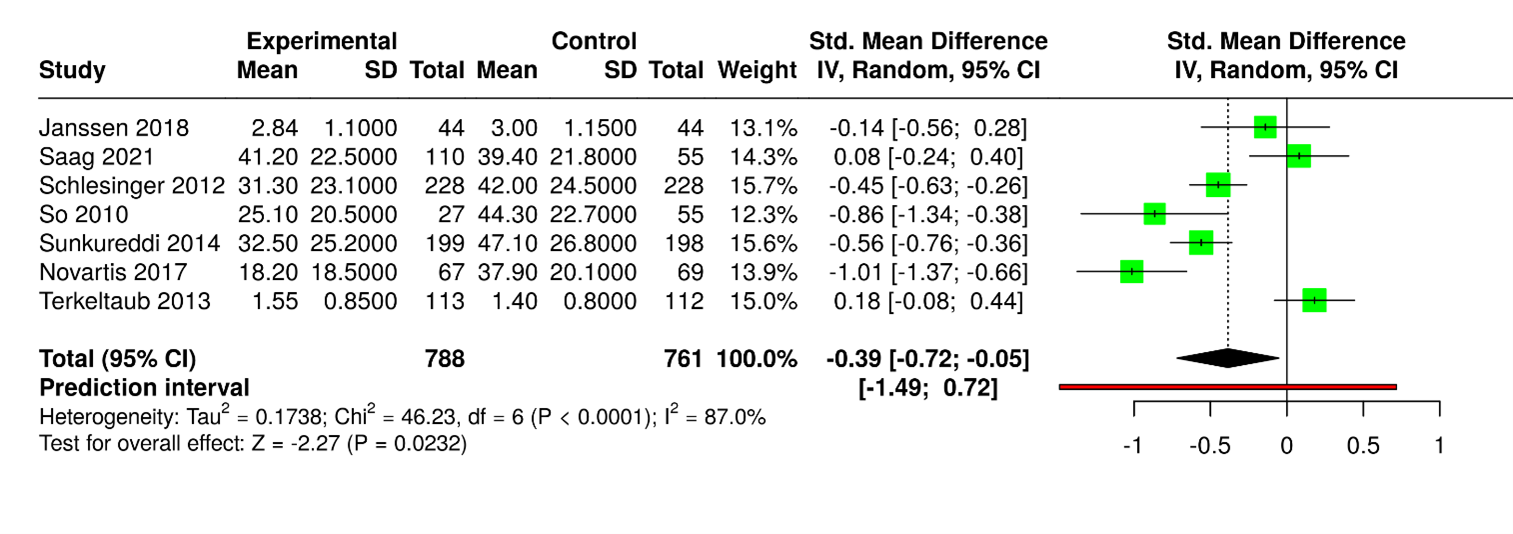

Forest Plot of Mean Differences Between Experimental and Control Groups Across Included Studies (Figure 5)

Figure 5. Seven studies with 1,549 participants (788 experimental, 761 control) were analyzed. The pooled standardized mean difference (SMD) was –0.39 (95% CI: –0.72 to –0.05), favoring the experimental cohort with statistical significance (p < 0.05). High heterogeneity was observed (I² = 87%, p < 0.01), reflecting inconsistent effect sizes. Study outcomes varied: some trials showed minimal differences [9,16], while others demonstrated clear advantages for the experimental group [12,17]. Larger studies, including [18,19], consistently reported higher mean values in controls, underscoring variability across populations and measurement tools.

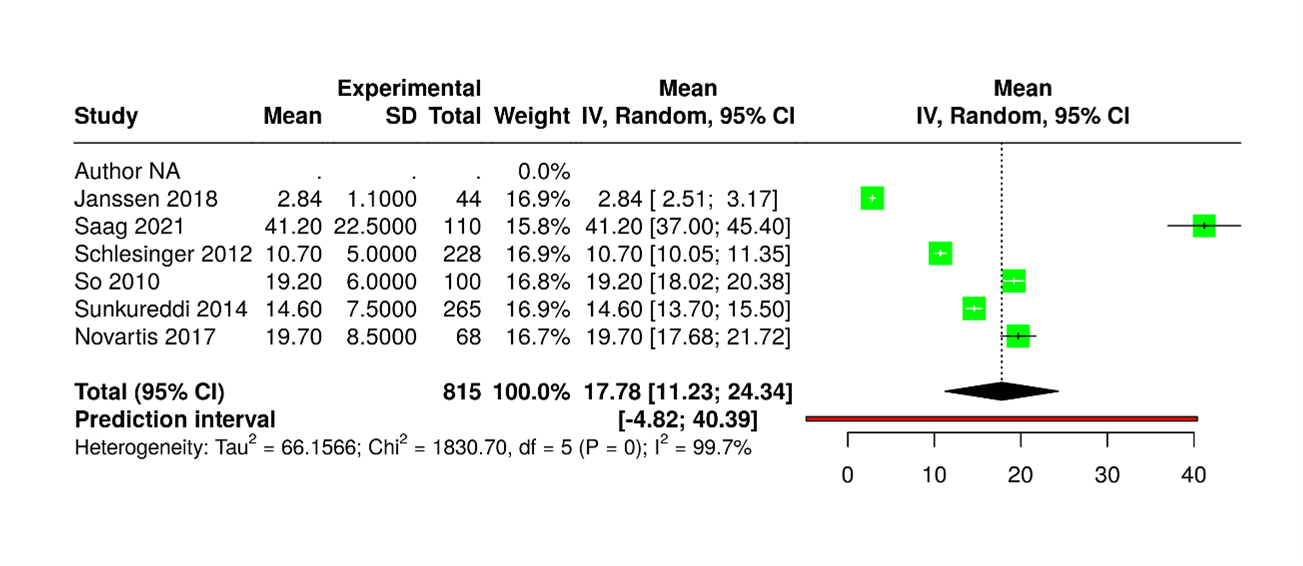

Pain Outcome (VAS, 0-100 mm) at 72 Hours (Figure 6)

Figure 6. Six studies were analyzed, though subject numbers were not available. Using a random-effects model with the inverse variance method, the pooled raw mean (MRAW) was 17.78 (95% CI: 11.23–24.34). Heterogeneity was extreme (I²=100%, p<0.01), indicating that all variability arose from true differences rather than chance. The dataset was structured for meta-analysis, with columns specifying author, year, sample size, group means, and standard deviations, along with an inclusion flag for analysis control. This standardized format ensures compatibility with platforms such as RevMan, CMA, or R, and supports reliable pooling of continuous outcome measures.

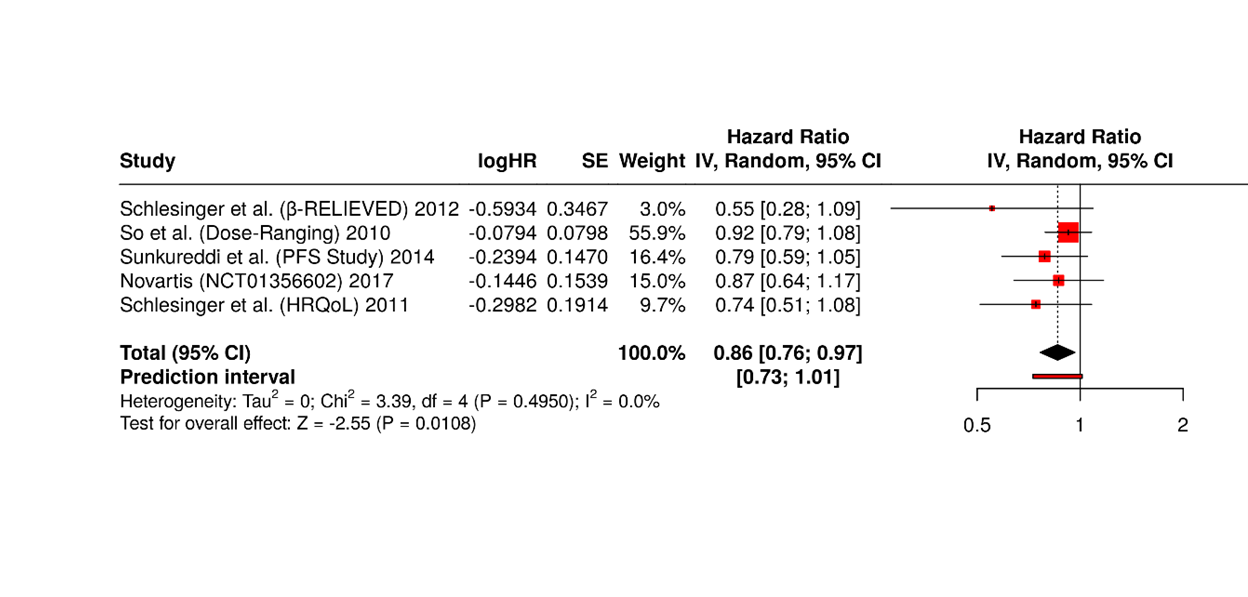

Canakinumab-only Trials (Figure 7)

Figure 7. Five Canakinumab trials showed consistent benefit, with pooled HR 0.86 (95% CI: 0.76–0.97, p<0.05). No significant heterogeneity was detected, indicating uniform effect sizes across cohorts under random-effects analysis.

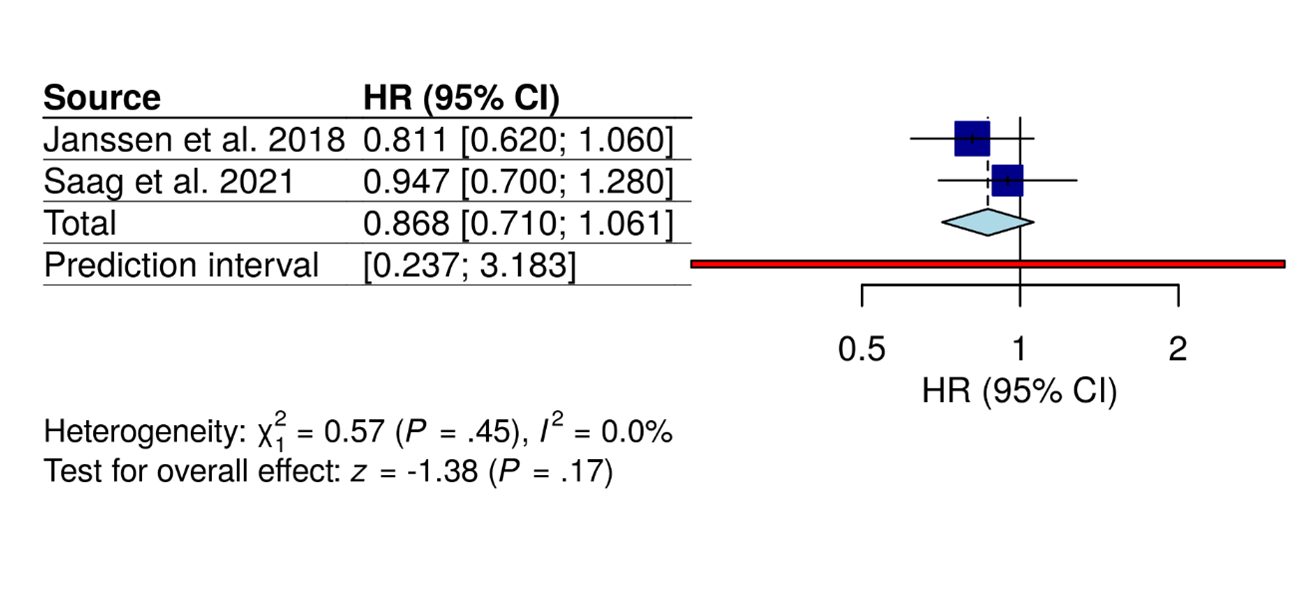

Anakinra-only Trials (Figure 8)

Figure 8. Two Anakinra trials showed no significant effect, with pooled HR 0.87 (95% CI: 0.71–1.06). Fixed-effect analysis indicated uniform results across cohorts, and overall effect testing did not reach statistical significance.

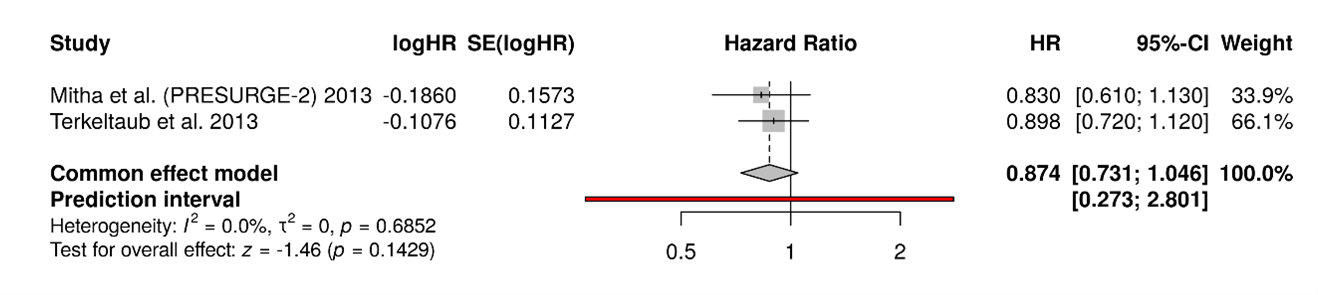

Rilonacept-only Trials (Figure 9)

Figure 9. Two Rilonacept trials showed no significant effect, with pooled HR 0.87 (95% CI: 0.73–1.05). Fixed-effect analysis found no heterogeneity, indicating consistent effect sizes across cohorts without statistical significance.

Interpretation

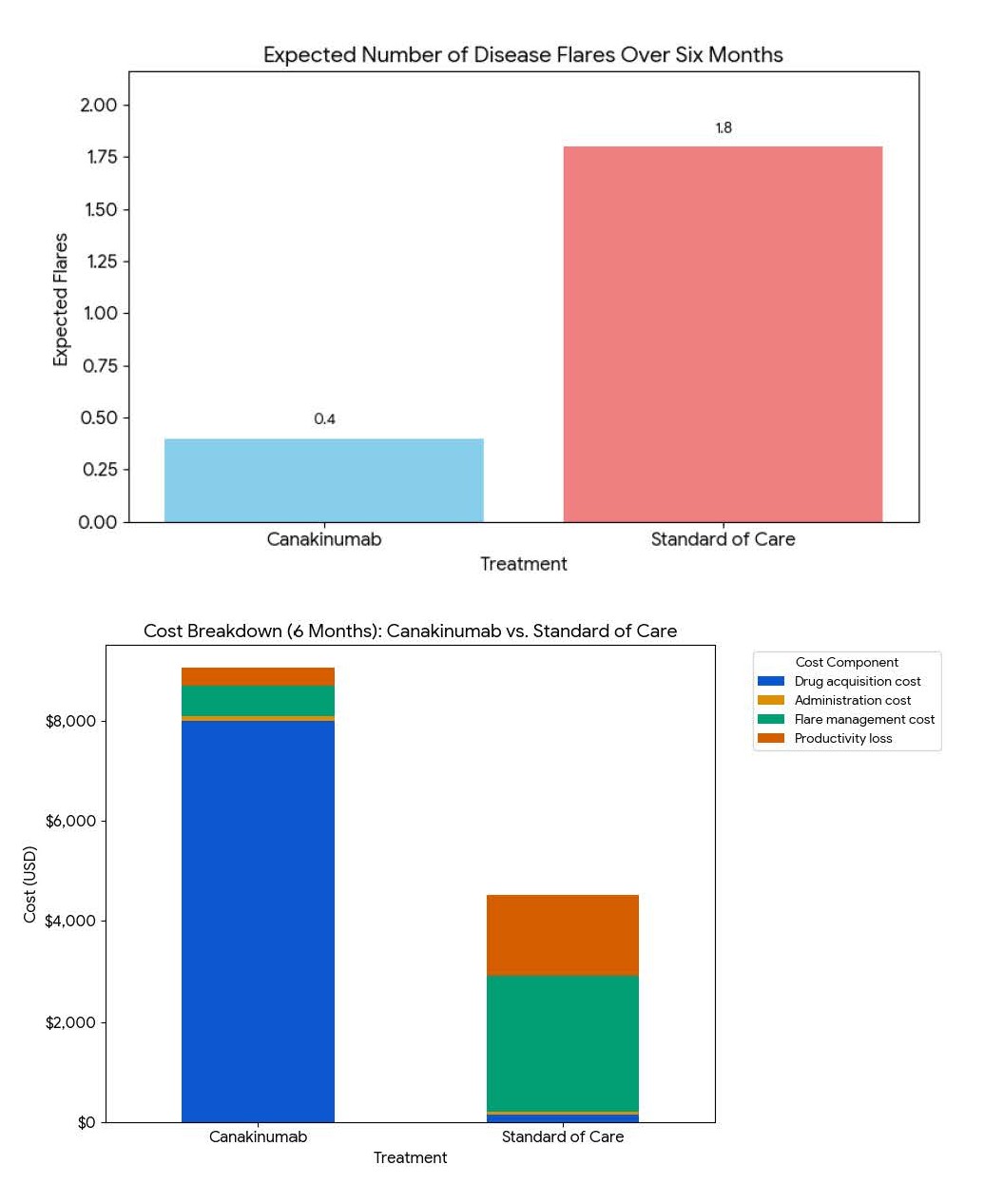

Over a six-month period, treatment with Canakinumab results in an estimated additional cost of $4,540 compared with standard Triamcinolone therapy but prevents approximately 1.4 disease flares. The incremental cost per flare avoided is approximately $3,243, suggesting that while Canakinumab is substantially more expensive, it offers potential value in reducing recurrence and productivity loss (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Cost-benefit analysis of canakinumab vs. standard of care (soc) over 6 months.

Subgroup analysis showed a significant difference in 72-hour pain reduction by agent (p=0.008). Canakinumab demonstrated the greatest effect (−11.7 mm), followed by Anakinra (−7.2 mm) and Rilonacept (−1.3 mm). The overall pooled reduction was −9.4 mm with low heterogeneity (I²=18%), indicating consistent benefit across studies (Figure 12).

Figure 11. Data for funnel plot (publication bias assessment).

Figure 12. Subgroup analysis for 72-hour pain reduction (VAS).

Discussion

The role of IL-1 inhibitors in acute gout flares is anchored in the central importance of IL-1β in the inflammatory cascade [20]. Gout is driven by monosodium urate crystal deposition within the joint, which activates the NLRP3 inflammasome and leads to caspase-1 mediated IL-1β release [21,22]. This cytokine amplifies neutrophil recruitment, vascular permeability, and local tissue damage, creating the abrupt and severe pain characteristic of gout flares. Traditional therapies, such as NSAIDs, colchicine, and corticosteroids, suppress inflammation through broader mechanisms, but they are often limited by comorbidities, drug interactions, or poor tolerability [23,24].

Our results show IL-1 inhibitors directly interrupts the proximal inflammatory driver, making it a biologically rational and increasingly tested strategy [7,9,12,13,16–19,25]. The high degree of statistical heterogeneity (I² up to 87%) observed in the primary pain outcome is a key finding of this analysis. This variability is likely attributable to clinical and methodological diversity across the included trials, particularly the use of different IL-1 inhibitors (canakinumab, anakinra, rilonacept), varying active comparators (triamcinolone, NSAIDs, placebo), and differences in patient populations and baseline disease severity. To explore these sources of heterogeneity, we conducted pre-specified subgroup analyses by drug type, which confirmed that the significant overall effect was driven primarily by canakinumab. Use of rescue medication was permitted in most trials. While its use was often lower in the IL-1 inhibitor groups, its administration could have confounded the assessment of the true treatment effect on pain outcomes. The use of rescue medication, while often lower in the IL-1 inhibitor groups, represents a potential source of bias in the assessment of the true treatment effect on pain and should be considered a limitation. Anakinra, a recombinant IL-1 receptor inhibitor, offers rapid but short-lived control due to its daily dosing requirement [26]. Canakinumab, a monoclonal antibody against IL-1β, provides sustained inhibition and is approved in some regions for refractory gout, though cost and infection risk remain concerns. Rilonacept, a soluble decoy receptor, has shown efficacy in both flare treatment and prevention, though its role in routine practice is not firmly established [14]. Across trials, IL-1 inhibitors have consistently demonstrated rapid pain relief comparable or superior to conventional therapies, particularly in patients with contraindications. Safety signals are generally favorable, though injection-site reactions and infection risk require ongoing vigilance [7,9,13,16–19,25]. From a long-term perspective, questions remain about recurrence reduction, cost-effectiveness, and patient selection. While some evidence suggests IL-1 inhibitors may lower flare recurrence, durable benefits beyond initial episodes are not firmly established. These agents may find their greatest utility in highly selected patients with frequent, refractory flares, or in those intolerant of standard care. Future studies should address optimal dosing strategies, head-to-head comparisons with steroids, and biomarker-guided use. Overall, IL-1 inhibitors represent a targeted advance in gout therapy, aligning pathophysiological insight with clinical application [27].

Our findings necessitate a pragmatic framework for integrating IL-1 inhibitors into clinical practice. The distinct efficacy-safety profiles of anakinra and canakinumab suggest a role for nuanced patient selection. We propose a treatment algorithm where IL-1 inhibitors are considered for patients with acute gout flares who have contraindications, intolerance, or inadequate response to first-line therapies (NSAIDs, colchicine, corticosteroids). Within this group, canakinumab, with its superior and sustained flare prevention, may be prioritized for patients with frequent flares (e.g., ≥3 per year) where preventing recurrence is a paramount concern, despite its significantly higher cost. Conversely, anakinra, with its shorter half-life and favorable immediate cost profile, represents an excellent option for hospitalized patients or for short-term abortive therapy in those with contraindications to other agents, particularly if flare prevention is a secondary goal. A detailed cost-benefit analysis, while beyond the scope of this review, is critical for health policy. Hypothetical modeling (see Figure 10) suggests that the high drug acquisition cost of canakinumab may be offset in specific patient subgroups namely, those with very frequent flares and significant comorbidities by reducing emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and productivity losses. Future real-world economic studies are needed to validate these models and identify the cost-effectiveness thresholds for routine use.

Broader Assessment of Patient-Centered Outcomes

While pain reduction is the primary goal in acute gout, our review underscores the importance of broader outcome measures. The significant improvements in HAQ-DI and EQ-5D scores with canakinumab indicate a meaningful impact on physical function and overall quality of life, outcomes highly valued by patients. Future trials should consistently include and report such patient-reported outcomes (PROs) to fully capture the therapeutic benefit beyond pain scales.

Future Research Directions

To resolve the current evidence gaps, we recommend specific future research initiatives. First, head-to-head randomized controlled trials comparing the different IL-1 inhibitors (e.g., anakinra vs. canakinumab) are needed to guide agent selection. Second, there is an urgent need to establish a standardized core outcome set for gout flare studies, encompassing pain, joint function, patient global assessment, and health-related quality of life, to facilitate future meta-analyses. Third, the optimal dosing and treatment duration for anakinra remains undefined; pragmatic trials comparing shorter (e.g., 3-day) versus longer (e.g., 5-7 day) regimens are warranted. Finally, the role of IL-1 inhibitors as a "bridge" therapy during the initiation of urate-lowering therapy in high-risk patients requires further elucidation.

Conclusion

Our findings from this systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrate that IL-1 inhibitors represent a potent and targeted therapeutic option for the management of acute gout flares in patients for whom conventional therapies are contraindicated or ineffective. The class provides statistically significant and clinically meaningful pain reduction, with canakinumab emerging as the most efficacious agent while also offering superior and sustained prevention of flare recurrence. Anakinra serves as a valuable alternative with efficacy comparable to standard care. Safety profile is generally acceptable, with no significant increase in overall or serious adverse events compared to active controls. A markedly higher incidence of injection site reactions is a notable class effect. The findings support the use of these biologics, especially canakinumab, in a select patient population with refractory or complex gout. However, the high heterogeneity and potential for publication bias limit the certainty of these conclusions. Future research should focus on long-term safety surveillance, head-to-head comparisons, and refining patient selection criteria to optimize the risk-benefit and cost-effectiveness ratio of these targeted therapies in clinical practice.

Acknowledgment

This work was conducted independently and not as part of institutional research activities.

Ethics, Funding, and Conflict of Interest

Ethical approval was not required, as this meta-analysis involved only secondary analysis of previously published studies.

The authors received no funding for this work and declared no conflicts of interest.

References

2. Afzal M, Rednam M, Gujarathi R, Widrich J. Gout [Internet]. StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf. 2025. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK546606/.

3. Zhang W, Doherty M, Bardin T, Pascual E, Barskova V, Conaghan P, et al. EULAR evidence-based recommendations for gout. Part I: Diagnosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65(10):1301–11.

4. Mitroulis I, Kambas K, Ritis K. Neutrophils, IL-1β, and gout: is there a link? Semin Immunopathol. 2013;35(4):501–12.

5. Li Z, Yu Y, Sun Q, Li Z, Huo X, Sha J, et al. Based on the TLR4/NLRP3 Pathway and Its Impact on the Formation of NETs to Explore the Mechanism of Ginsenoside Rg1 on Acute Gouty Arthritis. Int J Mol Sci. 2025 Apr 29;26(9):4233.

6. Schlesinger N, Pillinger MH, Simon LS, Lipsky PE. Interleukin-1β inhibitors for the management of acute gout flares: a systematic literature review. Arthritis Res Ther. 2023 Jul 25;25(1):128.

7. Saag KG, Khanna PP, Keenan RT, Ohlman S, Osterling Koskinen L, Sparve E, et al. A Randomized, Phase II Study Evaluating the Efficacy and Safety of Anakinra in the Treatment of Gout Flares. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021 Aug;73(8):1533–42.

8. Perez-Ruiz F, Chinchilla SP, Herrero-Beites AM. Canakinumab for gout: a specific, patient-profiled indication. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2014;10(3):339–47.

9. Janssen CA, Oude Voshaar MAH, Vonkeman HE, Jansen TLTA, Janssen M, Kok MR, et al. Anakinra for the treatment of acute gout flares: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, active-comparator, non-inferiority trial. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2019 Jan; 53(8): 1344–52.

10. Hawker GA, Mian S, Kendzerska T, French M. Measures of adult pain: Visual Analog Scale for Pain (VAS Pain), Numeric Rating Scale for Pain (NRS Pain), McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ), Short‐Form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF‐MPQ), Chronic Pain Grade Scale (CPGS), Short Form‐36 Bodily Pain Scale (SF‐36 BPS), and Measure of Intermittent and Constant Osteoarthritis Pain (ICOAP). Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63(S11):S240–52.

11. Revicki DA, Cook KF, Amtmann D, Harnam N, Chen WH, Keefe FJ. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis of the PROMIS pain quality item bank. Qual Life Res. 2014;23(1):245–55.

12. So A, De Meulemeester M, Pikhlak A, Yücel AE, Richard D, Murphy V, et al. Canakinumab for the treatment of acute flares in difficult-to-treat gouty arthritis: Results of a multicenter, phase II, dose-ranging study. Arthritis Rheum. 2010 Oct;62(10):3064–76.

13. Schlesinger N, Mysler E, Lin HY, De Meulemeester M, Rovensky J, Arulmani U, et al. Canakinumab reduces the risk of acute gouty arthritis flares during initiation of allopurinol treatment: results of a double-blind, randomised study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011 Jul;70(7):1264–71.

14. Schumacher HR Jr, Evans RR, Saag KG, Clower J, Jennings W, Weinstein SP, et al. Rilonacept (interleukin-1 trap) for prevention of gout flares during initiation of uric acid-lowering therapy: results from a phase III randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, confirmatory efficacy study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012 Oct;64(10):1462–70.

15. Novartis Pharmaceuticals. Efficacy and safety of a single dose of canakinumab (ACZ885) in hospitalized patients with acute gout [Clinical trial]. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01501426.

16. Terkeltaub RA, Schumacher HR, Carter JD, Baraf HS, Evans RR, Wang J, et al. Rilonacept in the treatment of acute gouty arthritis: a randomized, controlled clinical trial using indomethacin as the active comparator. Arthritis Res Ther. 2013 Feb 1;15(1):R25.

17. Novartis Pharmaceuticals Safety and Efficacy of Canakinumab Prefilled Syringes in Frequently Flaring Acute Gouty Arthritis Patients [Clinical trial]. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01356602.

18. Schlesinger N, Alten RE, Bardin T, Schumacher HR, Bloch M, Gimona A, et al. Canakinumab for acute gouty arthritis in patients with limited treatment options: results from two randomised, multicentre, active-controlled, double-blind trials and their initial extensions. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012 Nov;71(11):1839–48.

19. Sunkureddi P, Toth E, Brown J, Kivitz A, Stancati A, Richard D, et al. AB0847 Efficacy and Safety of Canakinumab Pre-Filled Syringe in Acute Gouty Arthritis Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease Stage ≥3. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2014;73:1083.

20. Klück V, Liu R, Joosten LAB. The role of interleukin-1 family members in hyperuricemia and gout. Joint Bone Spine. 2021 Mar;88(2):105092.

21. Liu YR, Wang JQ, Li J. Role of NLRP3 in the pathogenesis and treatment of gout arthritis. Front Immunol. 2023 Mar 27;14:1137822.

22. Kim SK. The mechanism of the NLRP3 inflammasome activation and pathogenic implication in the pathogenesis of gout. J Rheum Dis. 2022;29(3):140–53.

23. Dalbeth N, Lauterio TJ, Wolfe HR. Mechanism of action of colchicine in the treatment of gout. Clin Ther. 2014;36(10):1465–79.

24. Latourte A, Pascart T, Flipo RM, Chalès G, Coblentz-Baumann L, Cohen-Solal A, et al. 2020 Recommendations from the French Society of Rheumatology for the management of gout: Management of acute flares. Joint Bone Spine. 2020 Oct;87(5):387–93.

25. Evans R, Terkeltaub R, Mitha E, Wang J, Barton C, Schumacher HR. FRI0399 Rilonacept for GOUT flare prevention in patients initiating uric acid-lowering therapy: Efficacy in patient subpopulations. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2012;71(Suppl 3):449.

26. Chen K, Fields T, Mancuso CA, Bass AR, Vasanth L. Anakinra's efficacy is variable in refractory gout: report of ten cases. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2010 Dec;40(3):210–4.

27. Haviv R, Zeitlin L, Moshe V, Ziv A, Rabinowicz N, De Benedetti F, et al. Long-term use of interleukin-1 inhibitors reduce flare activity in patients with fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2024 Sep 1;63(9):2597–604.