Abstract

Background: The concurrent use of tramadol and khat has been increasing in Ethiopia, raising concerns about their potential neurocognitive consequences. Despite growing trend, the effects of combined tramadol and khat exposure on learning and memory (LM) have not been previously investigated. Accordingly, the present study was designed to evaluate the impact of co-administration of khat and tramadol on spatial learning and memory in a mouse model.

Materials and Methods: Mice were grouped in four treatments, i.e., control (2% Tween 80), khat (300 mg/kg), tramadol (20 mg/kg), and khat and tramadol co-administered (300 mg/kg and 20 mg/kg, respectively). The Morris Water Maze (MWM) model was used to assess spatial LM. The data were analyzed, and a p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results: In the acquisition phase, all groups improved in the ability to detect the hidden platform that training days had a significant effect, [F (3,26) =3.256, p<0.05]. Compared to the controls, the tramadol-treated group showed significantly longer escape latencies on Day 1 (p<0.05). Based on short-term memory (STM) tests, all treatment groups spent less time in the target quadrant (NW) than the control group (p<0.001). In long-term memory (LTM), the control group spent significantly more time in the NW quadrant (42.6±3.8 s) compared with the khat (27.4±4.2 s), tramadol (25.7±3.9 s), and combination groups (18.1±3.1 s) (p<0.001). The khat-treated group showed a significant difference compared to the combined khat- and tramadol-treated group (p<0.01).

Conclusion: The present study assessed the acute effects of khat, tramadol, and their combination on mice spatial memory using the Morris Water Maze. Tramadol impaired initial learning, and all treatments caused short- and long-term memory deficits, with the combination producing the greatest long-term impairment, suggesting additive or synergistic effects on hippocampal-dependent memory.

Keywords

Khat, Tramadol, Morris Water Maze, Murine, Learning and memory

Introduction

The brain serves as the foundation for the mind, influencing behavior, learning, memory, and various cognitive functions. Learning is a continuous process that allows individuals to acquire knowledge and modify behaviors based on experiences [1]. Hence, learned experiences have the power to change behavior and play a pivotal role in social interaction [2]. Memory, crucial for retaining information, involves multiple stages: acquisition, consolidation, storage, and retrieval [3,4]. Memory can be categorized into declarative (conscious, event-related) and non-declarative (unconscious, procedural), with differences made between short-term memory (STM) and long-term memory (LTM) [1,5].

Khat, or Catha edulis, is an evergreen shrub popular in Yemen and East Africa, known for its psychoactive properties when its young leaves are chewed [6]. The primary compound responsible for its stimulant effects is cathinone, which exhibits similarities to amphetamines [7]. Khat consumption has become significant in Ethiopia, valued at approximately $300 million, with a high prevalence among East African males [8,9]. The sociocultural context surrounding khat usage often intertwines with social gatherings, enhancing interactions and recreational activities [10].

The Ethiopian Food and Drug Authority (EFDA) recently classified tramadol as a narcotic substance, reiterating its potential for mental and physical addiction if abused. The EFDA reiterated the relevance of using tramadol under medical supervision to minimize the hazards associated with its abuse and to adhere to national drug rules [11].

Tramadol, a synthetic opioid analgesic, functions effectively for moderate to severe pain [12]. It works by modulating pain pathways and has demonstrated efficacy in managing various pain conditions [13,14]. Its dual mechanism involves opioid receptor agonists and the reuptake inhibition of norepinephrine and serotonin [15,16]. Its use has risen significantly in Ethiopia, raising serious public health concerns because of its misuse and addiction potential [17].

The relationship between learning, memory, khat, and tramadol is complex. Cathinone enhances catecholamine release, affecting neurotransmitter levels crucial for cognitive functions, including working memory [7]. Evidence suggests that long-term khat use can impair cognitive abilities, particularly in the prefrontal cortex, affecting memory and cognitive flexibility [18]. Similarly, tramadol impacts neurotransmitter systems, inhibiting NMDA and AMPA receptors essential for memory formation, leading to potential memory impairments through reduced neuroplasticity [19–21].

Khat consumption is prevalent in Eastern Africa and the Middle East, and it often enhances interaction during gatherings [22]. However, it also causes cognitive deficits, particularly among students and workers [23–25]. The concomitant use of tramadol and khat raises serious concerns regarding their potential additive effects on addiction and cognitive health, underscoring the need to investigate the neurocognitive consequences of their combined exposure.

Neuropharmacologically, khat and tramadol act via overlapping monoaminergic pathways and thus may produce interactive effects on cognition. The main psychoactive ingredient of khat, cathinone, exerts amphetamine-like actions by increasing synaptic dopamine and norepinephrine through enhanced release and reuptake inhibition. These catecholaminergic effects influence hippocampal plasticity, attention, arousal, and memory encoding [23]. In contrast, tramadol is a centrally acting analgesic that possesses a dual mechanism of action: weak µ-opioid receptor agonism and inhibition of serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake. By these mechanisms, tramadol may modulate GABAergic inhibition, monoamine signaling, and glutamatergic neurotransmission within memory-related brain regions, including the hippocampus [12,26]. Because both substances influence overlapping dopaminergic and noradrenergic circuits, concurrent exposure may promote either synergistic disruption of cognition due to excessive monoaminergic stimulation or antagonistic effects resulting from opioid-induced suppression of excitatory neurotransmission. These interactions may consequently alter hippocampal LTP, spatial learning, and memory consolidation. Despite the plausible neurobiological interplay between khat and tramadol, their combined effects on hippocampal-dependent cognitive functions have not been previously examined in experimental studies [7,27].

Although the two are commonly co-administered in various East African contexts, particularly among young adults who seek increased stimulation, their neurocognitive effects have been studied only individually. Research on khat has indeed documented deficits in working memory, cognitive flexibility, and processes that rely on the hippocampus, particularly with chronic use [7,18,28]. In contrast, tramadol administration has been associated with disrupted learning and memory due to modulation of NMDA/AMPA receptors, monoaminergic imbalance, and neurotoxicity in the hippocampus [12,26]. Despite the growing body of evidence on the independent neurocognitive effects of each drug, no prior investigation has determined whether their co-administration produces additive, synergistic, or distinct impairments in spatial learning and memory. It remains an important scientific and clinical necessity to fill the described research gap in light of an increasing number of cases of dual use of khat and tramadol and potential neurotoxic consequences in Ethiopia. Accordingly, the study was the first to examine the acute combined effects of khat and tramadol on spatial learning and memory using the Morris Water Maze, thereby providing novel evidence relevant to emerging public health concern.

Thus, the study aimed to evaluate the acute effects of khat and tramadol on spatial learning and memory in mice following single-dose administration using the Morris Water Maze (MWM) task.

Materials and Methods

Drugs and chemicals

Polysorbate 80 (Uni-Chem, India), Tramadol Hydrochloride (Loba Chemie Pvt. Ltd.), Chloroform (AR, Reagent Chemical Services Ltd.), Diethyl Ether (AR, Reagent Chemical Services Ltd., Cheshire, UK), and Distilled Water.

Plant material collection

The fresh bundles of khat shoots and small twigs were purchased from a local market in Awaday, located 515 km east of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. The bundles were carefully cleaned and packed in plastic bags before being transported in ice boxes to the laboratory of the Department of Pharmacology and Clinical Pharmacy at the School of Pharmacy, Addis Ababa University, in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. The freshly harvested leaves were promptly placed in a refrigerator set at -20°C (Bionics Scientific, India) for storage.

Extraction of crude khat

The extraction procedure was conducted following the methods described in previous studies [29–31]. The freshly harvested leaves were finely chopped using a knife in a dark environment. The chopped leaves were weighed using an electronic digital balance (Mettler Toledo scales and balances, Switzerland). The weighed leaves were then placed in an Erlenmeyer flask sourced (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, U.S.A.). The flask contained a mixture of organic solvents, specifically 150 ml of chloroform and 450 ml of diethyl ether, in a ratio of 1:3 v/v. Sufficient solvent was added to completely cover the crushed plant material in the flask. The flask was wrapped with aluminum foil (Silver Plate Factory L.L.C., U.A.E.). The contents of the flask were stirred continuously for 72 hours using a rotary shaker [New Brunswick Scientific Co. (USA)] at a speed of 120 rpm and a g-force of 0.13 (r = 0.8 cm). Following the stirring process, the mixture was filtered using Whatman No. 1 filter paper (Whatman Ltd, England) with a diameter of 90 mm. The resulting filtrate was concentrated for 24 hours in a fume bonnet (Guangdong Beta Laboratory Furniture Company Ltd., China). Finally, the extract was stored in a tight-sealed container at a temperature of -20°C until it was ready for use.

Experimental animals

The study utilized Sprague Dawley mice of either sex with a weight range of 20-30 g and an age range of 8-12 weeks. The mice were obtained from the animal house of the Department of Pharmacology and Clinical Pharmacy, School of Pharmacy, Addis Ababa University. They were housed in polypropylene cages with standard wood chip bedding and kept under controlled conditions with an average room temperature of 22°C (± 3°C) and a 12/12 h light-dark cycle. The mice were allowed access to food and water, Ad libitum. All animal handling and experimental procedures adhered to internationally accepted guidelines as specified by the OECD in 2008 and 2022.

Preparation of tramadol

The preparation procedure was conducted following the methods described in previous studies [26]. A fresh solution of tramadol hydrochloride was prepared using sterile 0.9% saline. The sample solution was prepared on the day of the experiment and administered to the respective mice.

Grouping and dosing of animals

Mice were randomly assigned to four experimental groups, with eight mice in each group. The first group received the vehicle, which was a 2% (v/v) Polysorbate 80 solution in water (CON). The second group was given 300 mg/kg of crude khat extract (K300) [32]. The third group received 20 mg/kg of tramadol hydrochloride (T20) [26], and the fourth group received both K300 [33] and T20 [26]. The administration of a single dose was done acutely, with tramadol being administered intraperitoneally (IP) and khat extract and the vehicle being administered orally (p.o.).

K300 sample solutions were prepared fresh, and the containers were covered with aluminum foil to prevent light-induced decomposition. The K300 was weighed and mixed with the vehicle to achieve a predetermined concentration, and continuous mixing was performed using a vortex shaker. The final volumes were adjusted to a uniform 1 ml with the vehicle, and oral gavage (Pet Surgical, USA) was employed for oral administration. The oral route was chosen since khat leaves are typically consumed orally by humans. Furthermore, pharmacokinetic studies have shown that khat is readily absorbed into the plasma from the stomach and mouth [34].

Morris Water Maze

The Morris Water Maze (MWM) model, which is widely utilized to investigate LM behavior in rodents [35], was initially developed by Richard Morris in 1981 [36] to evaluate spatial or place-based learning. One advantage of the task is that it can be learned quickly without the need for pre-training or restriction of food and water access [35]. The underlying concept of the task involves the animal learning to navigate to a hidden platform using either nearby or distant cues, starting from various random locations along the tank's perimeter [37].

The procedures outlined by Kimani and Nyongesa (2008) was followed with slight modifications for the experiment. A black, round polypropylene tank with a diameter of 150 cm and a depth of 50 cm was used as the Morris water maze (MWM). The tank was filled with tap water to a height of 31 cm, and an electric heater maintained the water temperature at room temperature (25°C±1°C) throughout the experimental period. An escape platform made of sturdy concrete cement, measuring 10 cm in diameter and 30 cm in height, was placed in the tank. The surface of the platform was covered with black plastic for camouflage, and it was submerged 1 cm below the water's surface to prevent visibility by the animals.

The tank was divided into four quadrants: Northwest (NW), Northeast (NE), Southeast (SE), and Southwest (SW). The boundaries of the quadrants were marked with tape on the pool's edges, and the labels north (N), south (S), east (E), and west (W) were assigned accordingly. Distal cues, such as colorful posters, were placed on the walls of the pool and room, remaining in the same position throughout the training and testing period. These cues are hypothesized to assist the animals in developing a spatial map for navigating to the platform. All tests were conducted at approximately the same time each day to minimize variations in performance due to diurnal factors. Animal performance in the MWM was recorded using an overhead video camera positioned above the water maze.

Habituation phase

Habituation was conducted immediately after administration in the acute dose study. Its purpose is to limit the stress associated with water exposure and teach the mice to remain on the platform. The phase was carried out in a room devoid of any external stimuli. After the mice are familiarized with the maze, they are allowed to swim in the pool for 60 seconds and are guided to the platform if they do not find it on their own. Once they discover the platform, they must remain on it for at least 3 seconds. The step was repeated until the mouse remained on the platform for 30 seconds and was not considered part of the spatial learning phase. Additionally, the mice were brought to the examination room one hour before the test each day. Each mouse was placed in the water by the tail, immediately opposite the boundary at one of the starting points (N, S, E, and W).

Acquisition phase

Spatial acquisition sessions took place in a room equipped with proximal and distal cues on the walls of the room and pool. The experiment commenced after 4 pm each day. The mice underwent 16 training sessions, with each session consisting of 4 trials conducted over 4 days. The objective of these sessions was to locate a submerged platform positioned at the center of the NW quadrant (target) in the MWM tank. The platform's location remained consistent throughout the 4-day training period. On each trial, the mice were randomly placed at one of the launch locations (N, S, W, and E). The order of the starting locations varied randomly to ensure that consecutive days did not repeat the same block of four trials/sessions in the same order. Each mouse had 60 seconds to search for the platform. Upon locating the platform, the mouse was allowed to remain on it for 30 seconds. The primary goal of staying on the platform was for the animal to orient itself to its spatial position and remember the platform's location relative to the surrounding cues. The escape latency, which is the time taken by the mouse to travel from the start position to the escape platform, was measured using a stopwatch. If an animal failed to identify the platform within the allotted time, it was placed on the platform for 30 seconds and assigned a latency of 60 seconds. After each trial, the mice were removed from the water, dried using a towel and a rodent heater set at 36 to 38°C, and then returned to their home cages. The intertrial interval (ITI) for each animal was 5 minutes.

Retention trials

The trial test for short-term memory (STM) was conducted on the fifth day, 24 hours after the completion of the acquisition recording. Each mouse underwent a 60-second probe trial in which the escape platform was completely removed. The mouse was moved from position S to the target quadrant (NW) in the MWM tank, as done during the acquisition phase. The amount of time spent in the target quadrant was determined from the video recording and used as a measure of spatial STM. Additionally, the time spent in the adjacent quadrant (NE) was determined for comparison purposes. The memory retention was represented by the time spent in the target quadrant during the probe trial. The probe trial for long-term memory (LTM) was conducted on day 12, after a gap of 7 days following the STM probe trial. The procedure followed the same protocol as that used for the STM test.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software, version 26.0. A two-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to analyze performance during the acquisition phase (learning phase). For the memory test, the paired-samples t-test was used to assess quadrant preference in MWM, while the one-way ANOVA followed by a post hoc test (Tukey test) was utilized to evaluate differences in the mean between the groups for latency in MWM. The analysis was conducted at a 95% confidence interval, and p<0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses.

Ethics approval statement

All procedures adhered to the guidelines outlined in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals [38]. The procedures received approval and ethical clearance (ERB/SOP/624/16/2024) from the Department of Pharmacology and Clinical Pharmacy at Addis Ababa University.

Results

Effect on learning

The results from the acquisition phase of the Morris Water Maze (MWM) task are presented in Table 1, which shows the mean latency to identify the hidden platform during the 4-day training period. All groups demonstrated a mastery of the task, as their mean time to locate the hidden platform decreased across the 4-day training.

|

CON |

18.43±3.75 |

17.71±3.10 |

17.84±3.24 |

15.18±4.12 |

17.29±3.49 |

|

K300 |

19.28±3.31*b |

26.18±5.87 |

24.68±4.82 |

12.62±2.20 |

20.69±3.49 |

|

T20 |

37.75±5.72*a |

24.56±4.39 |

28.09±5.89 |

22.69±4.09 |

28.34±3.49 |

|

K300 & T20 |

24.90±4.97 |

28.40±4.61 |

28.40±3.39 |

24.15±4.75 |

26.46±3.49 |

|

One-way ANOVA and two-way repeated measures ANOVA were used in the statistical analysis, and all results are mean±SEM (n=8); CON: vehicle (2% Tween 80); K300: khat 300 mg/kg; T20: Tramadol 20 mg/kg; K300 & T20: combination of khat 300 mg/kg and tramadol 20 mg/kg; a: treatment group compared to the control group; b: significant difference of khat compared with tramadol *: p<0.05. |

|||||

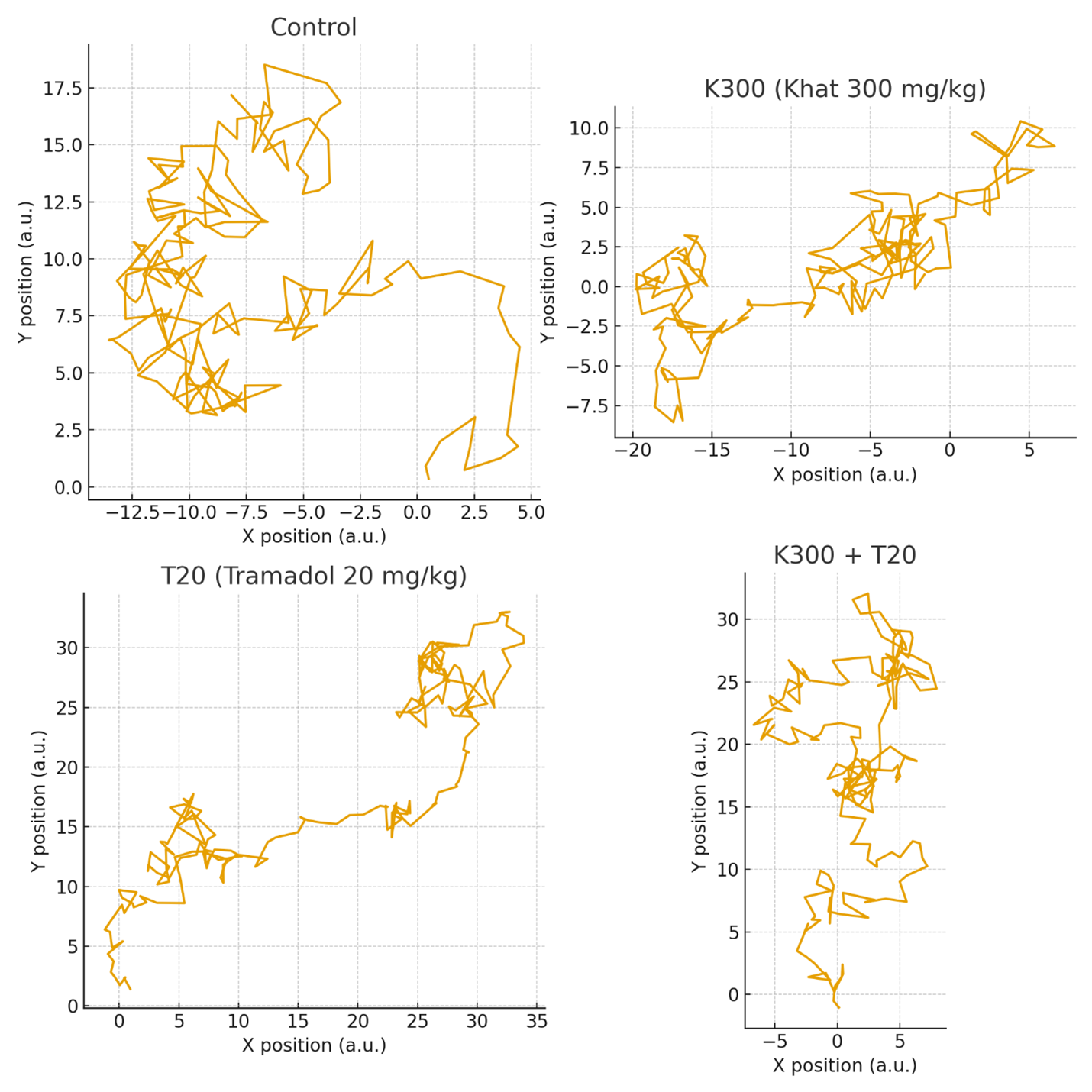

Based on the findings, there was an improvement among the treatment groups and the control group in learning the task, i.e., finding the hidden platform on each training day. A two-way repeated measure ANOVA test on the performance measures revealed a significant effect of days (F(3,26) = 3.256, p<0.05). However, the treatment groups did not show a significant effect, and the within-subjects effect showed no significant interaction between treatment groups and days (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Swim-path trajectories for the four experimental groups during the Morris Water Maze task. Each panel illustrates a typical navigation pattern toward the hidden platform. The Control group shows organized, goal-directed swimming, whereas K300, T20, and K300 + T20 groups exhibit increasingly fragmented and inefficient search patterns.

Post hoc Tukey's multiple comparison tests revealed that there was no statistically significant difference between the negative control group and the treated groups with khat, tramadol, or the combination of khat and tramadol across the four days of training in finding the hidden platform.

Regarding the performance of individual treatments, while khat and the combination of khat and tramadol did not produce any detectable difference, tramadol (p<0.05) resulted in a significantly lower performance (higher escape latency) compared to controls on Day 1. Additionally, a comparison between the khat and tramadol groups revealed a significant difference (p<0.05) on Day 1. A two-way repeated measure ANOVA showed no significantly higher performance in mice treated with khat, tramadol, and the combination of khat and tramadol when compared to the negative control group across the four training days (Table 1).

Effect on memory

The results from the probe trials for short-term memory (STM) and long-term memory (LTM) in the Morris Water Maze (MWM) task are presented in Tables 2 and 3, respectively.

|

Groups |

Time at NW |

Time NE |

|

CON |

25.75±1.79 |

11.25±2.19 |

|

K300 |

13.25±2.64*** |

11.50±1.89 |

|

T20 |

8.12±1.60*** |

7.89±1.12 |

|

K300 & T20 |

7.37±1.11*** |

9.68±2.22 |

|

Paired sample T-test and One-way ANOVA were used in the statistical analysis, and all results are mean±SEM (n=8); CON: vehicle (2% Tween 80); K300: khat 300 mg/kg; T20: Tramadol 20 mg/kg; K300 & T20: combination of khat 300 mg/kg and tramadol 20 mg/kg; NW: Northwest (target) quadrant; NE: Northeast (adjacent) quadrant ***: p<0.001. |

||

|

Groups |

Time at NW |

Time NE |

|

CON |

21.50±1.264 |

17.62±1.84 |

|

K300 |

11.87±1.74*** |

10.37±2.57 |

|

T20 |

7.25±2.18*** |

5.75±2.05 |

|

K300 & T20 |

4.00±0.32*** |

6.25±1.25 |

|

Paired sample T-test and One-way ANOVA were used in the statistical analysis, and all results are mean±SEM (n=8); CON: vehicle (2% Tween 80); K300: khat 300 mg/kg; T20: Tramadol 20 mg/kg; K300 & T20: combination of khat 300 mg/kg and tramadol 20 mg/kg; NW: Northwest (target) quadrant; NE: Northeast (adjacent) quadrant ***: p<0.001. |

||

For the STM test, which was conducted on the 5th day, a paired sample t-test revealed a statistically significant difference (t = 2.035, p = 0.050) in the time spent by the mice in the target quadrant (NW) compared to the adjacent quadrant (NE). Mice from all treatment groups spent more time in the target quadrant (NW) than in the adjacent quadrant (NE). Additionally, one-way ANOVA analysis indicated that the mice treated with the vehicle spent significantly more time (p<0.001) in the target quadrant compared to the mice treated with khat, tramadol, and their combination. Moreover, there was no statistically significant difference in time spent on the target quadrant between the respective treatment groups relative to each other.

In contrast, for the LTM test, the paired sample t-test revealed a non-significant difference in the time spent by the mice in the target quadrant versus the adjacent quadrant across all groups. However, the between-group comparison showed apparent differences among the different treatment groups. The one-way ANOVA analysis revealed that the mice treated with the vehicle spent significantly more time in the target quadrant compared to the mice treated with khat (p<0.001), tramadol (p<0.001), and their combination (p<0.001) during the LTM study. In addition, in the LTM study, a significance (p<0.01) in time spent in the NW quadrant was revealed between mice treated with khat and mice treated with a combination of khat and tramadol (Table 2).

Table 3 describes the performance of mice in the long-term memory (LTM) test using the Morris Water Maze, with data expressed as mean latency (in seconds) for time spent in the target quadrant (NW) and adjacent quadrant (NE). The control group (CON) spent an average of 21.50 seconds in the northwest quadrant and 17.62 seconds in the northeast quadrant. Mice treated with khat (300 mg/kg) spent significantly less time in the NW quadrant, averaging 11.87 seconds (p < 0.001), and 10.37 seconds in the NE quadrant. Those given tramadol (20 mg/kg) had considerably reduced latencies, averaging 7.25 seconds in the NW quadrant (p<0.001) and 5.75 seconds in the NE quadrant. Mice administered both khat and tramadol spent the least time in the NW quadrant, average 4.00 seconds (p<0.001), and 6.25 seconds in the NE quadrant. Statistical analysis revealed that all treatment groups (K300, T20, and K300 & T20) performed considerably worse in the target quadrant than the control group, indicating that these treatments may impair long-term memory.

Discussion

The impact of khat and the impact of tramadol separately on spatial learning and memory have previously been thoroughly evaluated by a few scholars [12,39–42]. These days, khat chewers tend to use tramadol as an add-on boost to obtain a potentiated stimulation, especially students of high school and tertiary educational institutions and young adults in Ethiopia. However, the combined effect of khat and tramadol has never been the subject of study. Therefore, the goal of the current study was to determine the combined effect of khat and tramadol on spatial learning and memory.

In the present study, learning and memory were assessed by the Morris Water Maze through acquisition and probe trials, respectively. All groups showed a progressive reduction in measured values over the four training days, reflecting acquisition of learning. Khat alone and its combination with tramadol did not have a significant effect on spatial learning. The finding that khat did have a discernible effect on memory is consistent with previous studies. Studies suggest that there is a biological plausibility that chronic khat use may induce memory deficits and impair cognitive flexibility. The differential patterns of memory deficits observed may reflect the differences in dose effect as well as time-dependent impairment [43]. Moreover, recent evidence suggests that prolonged khat use may impair neurobehavioral functions, such as increased motor activity and decreased cognition, especially learning and memory [28]. Furthermore, another research study conducted using the Morris Water maze on young rats to study the effect of khat on memory, AchE enzyme activity, and body weight revealed that khat had an impairing effect on memory [43]. Moreover, a recent study conducted revealed that khat did not impair spatial learning. No significant difference in escape latency was observed when rats that received subacute khat extract were compared with vehicle-treated controls. These findings suggest that subacute administration of khat extract does not impair spatial learning [44], consistent with the results of the present study.

On the other hand, unlike the present finding, other studies suggested that khat has no effect on learning and memory. A recent study on the effects of khat showed that crude, alkaloid, and nonalkaloid fractions of khat had no impact on learning and memory [45]. These data were further corroborated by a study using the MTM test in mice, which found that acute khat exposure did not enhance spatial learning and memory compared with control groups [6].

Whereas tramadol had an apparent effect on spatial learning on Day 1 compared to the other groups and continued to improve with no significance in the following three days. The finding indicated that learning occurred over the subsequent days. Studies have found that tramadol has an effect on learning and memory [12]. In addition, research conducted on the effects of tramadol and codeine revealed that exposure to tramadol can impair learning and memory [46]. Another research study conducted on the effects of tramadol has shown that it impairs memory when administered acutely or chronically [26]. Single-dose administration of tramadol showed more destructive effect on memory than multiple doses of tramadol [26].

Moreover, the current study demonstrated that all treatment groups exhibited statistically significant impairments in both short-term and long-term memory compared to the control groups. In the assessment of short-term memory, no significant difference was observed in the time spent in the target quadrant among the treatment groups. However, in the long-term memory test, a significant difference was noted between the khat-treated group and the group receiving both khat and tramadol, suggesting a compounded effect. These findings are consistent with those of Hosseini-Sharifabad et al. (2016), who reported that both acute and chronic tramadol administration impaired spatial memory in rats [26]. Similarly, Kimani et al. (2016) found that khat extract significantly disrupted memory function in rodents [43]. In contrast, Seifu and Engidawork (2019) observed no significant cognitive impairment following single or repeated doses of khat extract fractions, highlighting potential variability in outcomes based on dosing regimen, extract composition, and exposure duration [45].

The interaction effect of combined administration of tramadol and khat was significant in the long- and short-term memory compared to the control. Furthermore, the combined effect had a significant difference compared to the effect of khat on the LTM test but not to that of the tramadol alone. These results could suggest the pronounced negative effects of khat on long-term memory when it was combined with tramadol. As there were no previous studies specifically investigating the combined effects of khat and tramadol on spatial learning and memory, it was difficult to directly compare our findings with the current available literature. While individual studies have documented the separate cognitive effects of khat or tramadol, the lack of prior research on their co-administration limits direct comparisons and highlights the novelty of our study.

Limitations of the study

The present study has certain limitations that warrant acknowledgment. The work relied solely on behavioral outcomes without accompanying histological, biochemical, or molecular analyses such as assessments of hippocampal BDNF expression, cholinergic markers, oxidative stress indices, or neuronal integrity, which would strengthen mechanistic interpretation of the observed deficits. These pharmacotoxicologic and metabolic differences between rodents and humans limit the direct extrapolation of the exact dosages (khat: 300 mg/kg, tramadol: 20 mg/kg) and acute effects observed in mice to the human context. The findings suggest a potential risk in the human population, especially considering the observed impairment in both STM and LTM across all treatment groups compared with controls. Future studies should incorporate neurochemical profiling, oxidative stress biomarkers, and immunohistochemical analyses of hippocampal and prefrontal regions, along with chronic exposure models, to provide more comprehensive mechanistic insight into khat-tramadol interactions.

Conclusion

The study examined the acute effects of khat, tramadol, and their combination on spatial learning and memory in mice using the Morris Water Maze. Tramadol impaired initial learning on Day 1, and all treatments produced significant short- and long-term memory deficits compared with controls, with the combined exposure causing the greatest long-term impairment. These results indicate potential additive or synergistic disruptions to hippocampal-dependent memory, warranting further research using chronic models and neurobiological analyses.

Data Availability Statement

The original dataset supporting the finding of the present study can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Funding Statement

No financial support was received for the research.

Conflict of Interest

There was no conflict of interest.

Author Contributions

All authors are involved in the conceptualization and method design of the study. Iman Yakutelarsh conducted experimental work and performed data analysis. Ermias Alemayehu Beriso contributed data analysis, manuscript drafting, editing, and revision. Alfoalem Araba Abiye was involved in data analysis, drafting, editing, supervision, and article revision. Wondmagegn Tamiru participated in supervision of the study, data proof analysis, manuscript drafting and revision, and proofread the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the Department of Pharmacology and Clinical Pharmacy, School of Pharmacy, Addis Ababa University, for allowing us laboratory facilities and equipment.

References

2. Bargiota SI, Bozikas VP. Psychobiology of Behaviour. Psychobiol Behav. 2019;49–72.

3. Albers RW, Price DL, Brady S, Siegel GJ. Basic Neurochemistry. Seventh Edition. Elsevier; 2005.

4. Ambrogi Lorenzini CG, Baldi E, Bucherelli C, Sacchetti B, Tassoni G. Neural topography and chronology of memory consolidation: A review of functional inactivation findings. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 1999;71:1–18.

5. Squire LR. Memory and the brain. New York (NY): Oxford University Press;1987.

6. Assefa S, Girma A, Semu E, Moges S. The effect of acute exposure to crude khat (Catha edulis F.) on spatial learning and memory in mice using multiple T-maze test. J Pharmacogn Phytochem. 2018;7:2736–9.

7. Kimani ST, Nyongesa AW. Effects of single daily khat (Catha edulis) extract on spatial learning and memory in CBA mice. Behav Brain Res. 2008;195:192–7.

8. Cochrane L, O’Regan D. Legal harvest and illegal trade: Trends, challenges, and options in khat production in Ethiopia. Int J Drug Policy. 2016;30:27–34.

9. Tesfaye E, Krahl W, Alemayehu S. Khat induced psychotic disorder: case report. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2020;15:1–5.

10. Nencini P, Ahmed AM. Khat consumption: a pharmacological review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1989;23:19–29.

11. Ausman JI. In this issue... Surg Neurol. 2003;60:369–70.

12. Baghishani F, Mohammadipour A, Hosseinzadeh H, Hosseini M, Ebrahimzadeh-bideskan A. The effects of tramadol administration on hippocampal cell apoptosis, learning and memory in adult rats and neuroprotective effects of crocin. Metab Brain Dis. 2018;33:907–16.

13. Hollingshead J, Dühmke RM, Cornblath DR. Tramadol for neuropathic pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006 Jul 19;(3):CD003726.

14. Cepeda MS, Camargo F, Zea C, Valencia L. Tramadol for osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006 Jul 19;(3):CD005522.

15. Raffa RB, Friderichs E, Reimann W, Shank RP, Codd EE, Vaught JL. Opioid and nonopioid components independently contribute to the mechanism of action of tramadol, an’atypical’opioid analgesic. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992;260:275–85.

16. DESMEULES JA, Piguet V, Collart L, Dayer P. Contribution of monoaminergic modulation to the analgesic effect of tramadol. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1996;41:7–12.

17. Miotto K, Cho AK, Khalil MA, Blanco K, Sasaki JD, Rawson R. Trends in Tramadol: Pharmacology, Metabolism, and Misuse. Anesth Analg. 2017;124:44–51.

18. Colzato LS, Ruiz MJ, van den Wildenberg WPM, Hommel B. Khat use is associated with impaired working memory and cognitive flexibility. PloS One. 2011;6:e20602.

19. Abel T, Lattal KM. Molecular mechanisms of memory acquisition, consolidation and retrieval. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2001;11:180–7.

20. Bernabeu R, Schmitz P, Faillace MP, Izquierdo I, Medina JH. Hippocampal cGMP and cAMP are differentially involved in memory processing of inhibitory avoidance learning. Neuroreport. 1996;7:585–8.

21. Nakamura M, Minami K, Uezono Y, Horishita T, Ogata J, Shiraishi M, et al. The effects of the tramadol metabolite O-desmethyl tramadol on muscarinic receptor-induced responses in Xenopus oocytes expressing cloned M1 or M3 receptors. Anesth Analg. 2005;101:180–6.

22. Al-Mugahed L. Khat chewing in Yemen: turning over a new leaf: Khat chewing is on the rise in Yemen, raising concerns about the health and social consequences. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:741–3.

23. Kalix P. Khat: a plant with amphetamine effects. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1988;5:163–9.

24. Ageely HM. Prevalence of Khat chewing in college and secondary (high) school students of Jazan region, Saudi Arabia. Harm Reduct J. 2009;6:1–7.

25. Jager AD, Sireling L. Natural history of khat psychosis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1994;28:331–2.

26. Hosseini-Sharifabad A, Rabbani M, Sharifzadeh M, Bagheri N. Acute and chronic tramadol administration impair spatial memory in rat. Res Pharm Sci. 2016;11:49.

27. Lisman J. The Challenge of Understanding the Brain: Where We Stand in 2015. Neuron. 2015;86:864–82.

28. Ahmed A, Ruiz MJ, Kadosh KC, Patton R, Resurrección DM. Khat and neurobehavioral functions: A systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:1–18.

29. Bedada W, Engidawork E. The neuropsychopharmacological effects of Catha edulis in mice offspring born to mothers exposed during pregnancy and lactation. Phytother Res Int J Devoted Pharmacol Toxicol Eval Nat Prod Deriv. 2010;24:268–76.

30. Mohammed F, Engidawork E, Nedi T. The effect of acute and subchronic administration of crude Khat extract (Catha Edulis F.) on weight in mice. Am Sci Res J Eng Technol Sci ASRJETS. 2015;14:132–41.

31. Shewamene Z, Engidawork E. Subacute administration of crude khat (Catha edulis F.) extract induces mild to moderate nephrotoxicity in rats. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014 Feb 20;14:66.

32. Kassim S, Rogers N, Leach K. The likelihood of khat chewing serving as a neglected and reverse ‘gateway’to tobacco use among UK adult male khat chewers: a cross sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1–11.

33. Alele PE, Ajayi AM, Imanirampa L. Chronic khat (Catha edulis) and alcohol marginally alter complete blood counts, clinical chemistry, and testosterone in male rats. J Exp Pharmacol. 2013;33–44.

34. Toennes SW, Harder S, Schramm M, Niess C, Kauert GF. Pharmacokinetics of cathinone, cathine and norephedrine after the chewing of khat leaves. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;56:125–30.

35. Barnhart CD, Yang D, Lein PJ. Using the Morris water maze to assess spatial learning and memory in weanling mice. PloS One. 2015;10:e0124521.

36. Morris R. Developments of a water-maze procedure for studying spatial learning in the rat. J Neurosci Methods. 1984;11:47–60.

37. Vorhees CV, Williams MT. Morris water maze: procedures for assessing spatial and related forms of learning and memory. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:848–58.

38. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Test No. 425: Acute Oral Toxicity: Up-and-Down Procedure. OECD publishing; 2022.

39. Berihu BA, Asfeha GG, Welderufael AL, Debeb YG, Zelelow YB, Beyene HA. Toxic effect of khat (Catha edulis) on memory: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2024;8:30–7.

40. Ekpo UU, Umana UE, Sadeeq AA, Gbenga OP, Onimisi BO, Raji KB, et al. Tramadol induces alterations in the cognitive function and histoarchitectural features of the hippocampal formation in adult Wistar rats. J Exp Clin Anat. 2024;21:24–33.

41. Hassaan SH, Khalifa H, Darwish AM. Effects of extended abstinence on cognitive functions in tramadol-dependent patients: A cohort study. Neuropsychopharmacol Rep. 2021;41:371–8.

42. Mehdizadeh H, Pourahmad J, Taghizadeh G, Vousooghi N, Yoonessi A, Naserzadeh P, et al. Mitochondrial impairments contribute to spatial learning and memory dysfunction induced by chronic tramadol administration in rat: Protective effect of physical exercise. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2017;79:426–33.

43. Kimani ST, Patel NB, Kioy PG. Memory deficits associated with khat (Catha edulis) use in rodents. Metab Brain Dis. 2016;31:45–52.

44. Limenie AA, Dugul TT, Eshetu EM. Effects of Catha Edulis Forsk on spatial learning, memory and correlation with serum electrolytes in wild-type male white albino rats. PLoS ONE. 2022;17:1–16.

45. Seifu B, Engidawork E. Effect of Single and Repeated Dose Administration of Alkaloid, Non-alkaloid and Crude Extracts of Khat (Catha edulis Vahl. Endl.) on Spatial Learning and Memory in Mice. Ethiop Pharm J. 2019;35:95–110.

46. Kolawole Balogun S, Iheukwumere Osuh J, Olatunde Olotu O. Effects of Separate and Combined Chronic Ingestion of Codeine and Tramadol on Exploratory Learning Behaviour Among Male Albino Rats. Am J Appl Psychol. 2020;9:99.