Abstract

Background and objectives: Neuroinflammation is closely associated with various diseases including neuropathic pain. Microglia are immune cells in the central nervous system which are the main players of immunity and inflammation. Since microglia are activated by nerve injury, and they produce proinflammatory mediators to cause neuropathic pain, targeting activated microglia is considered to be a strategy for treating neuropathic pain. Activation of the cannabinoid CB2 receptor is known to have anti-inflammatory effects in microglia. ABK5-1 is a CB2 subtype selective agonist which inhibits IL-1β and IL-6 production in the microglia cell line BV-2. The purpose of the current study is to further analyze anti-inflammatory effects of ABK5 in terms of different cytokines and the possible pathway involved in the effect in the BV-2 cell line.

Methods: A cytokine array was performed to screen the effect of ABK5-1 on forty inflammatory mediators in BV-2 cells. Changes of the inflammatory mediators was further supported by mRNA analysis, and a possible signaling molecule that involved the observation was evaluated by western blot.

Results: Stimulating BV-2 cells by lipopolysaccharide increased expression of eleven inflammatory mediators, and ABK5-1 treatment resulted in more than a 50% decrease of sICAM1, IL-6, and RANTES. Real-time PCR results showed a decrease of G-CSF, ICAM1, MCP-1, MIP-1α, and MIP-1β mRNA levels. Western blot analysis showed that ABK5-1 inhibited LPS-induced ERK phosphorylation, which can be a mechanism of ABK5-1-mediated anti-inflammatory effect.

Conclusions: Our current results support the possibility that ABK5-1 is an anti-inflammatory drug for microglia.

Keywords

CB2 receptor, Cytokines, Chemokines, Inflammation, Microglia

Abbreviations

CNS: Central Nervous System; IL: Interleukin; LPS: Lipopolysaccharide; G-CSF: Granulocyte Colony-stimulating Factor; RANTES: Regulated upon Activation, Normal T cell Expressed and presumably Secreted; sICAM: soluble Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 1; MCP-1: Monocyte Chemotactic Protein 1; MIP: Macrophage Inflammatory Proteins; THC: Δ9- Tetrahydrocannabinol; TLR: Toll-like Receptor; TNF: Tissue Necrosis Factor

Introduction

Cannabis has been used for centuries for medical reasons and is known to have various beneficial impact such as antiinflammation and analgesic effects [1], while it may also cause some unwanted effects. Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is a well-studied component of cannabis which is known to cause these effects by binding both subtypes of cannabinoid receptors, CB1 and CB2. Cannabinoid receptors are GPCRs which primarily couple to Gi/o protein. Activation of cannabinoid receptors typically decreases cellular cAMP concentration (through coupling to Gi proteins), modulates the activity of ion channels, and induces signal transduction through various signaling pathways including ERK [2]. Since CB1 is mainly expressed in the central nervous system (CNS) and involved in control of neurotransmitter release [3,4]. While it expected to be a good target for some diseases, unwanted psychoactive side effects such as euphoria, dizziness, and impairment of memory are considered be associated with CB1 activation [5]. In contrast, although CB2 also can be found in some populations of cells in the CNS, its expression is mostly in immune cells and peripheral tissues [6,7], and activation of CB2 is reported to have anti-inflammation effects and analgesic effects without the psychoactivity [8-11]. Therefore, selectively targeting CB2 has been a good strategy for obtaining new drugs to treat inflammation and pain.

Microglia are macrophage-like cells in the CNS which play important role in immunity and homeostasis of the CNS. As immune cells, microglia are activated by pathogens and damaged cells, and remove the pathogens and dead cells through phagocytosis and production of inflammatory cytokines [12]. However, excessive and prolonged proinflammatory cytokine production by activated microglia causes various diseases including chronic pain [12-14]. Activation of microglia is known to be associated with neuropathic pain, which is one of major types of chronic pain [13,14]. Neuropathic pain is caused by nerve injury, and the damaged nerve releases mediators such as ATP, MMP-9 and other chemokines, which activate microglia [15]. Activated microglia releases pro-inflammatory cytokines including tissue necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-1β, and IL-6 [13,15]. These cytokines bind to their receptors in pre-synaptic and post-synaptic neurons and change expression and activity of receptors of neurotransmitters and ion channels [13], and result in change of excitability of neurons. These changes lead to allodynia and hyperalgesia, which are typical symptoms of neuropathic pain [16-18].

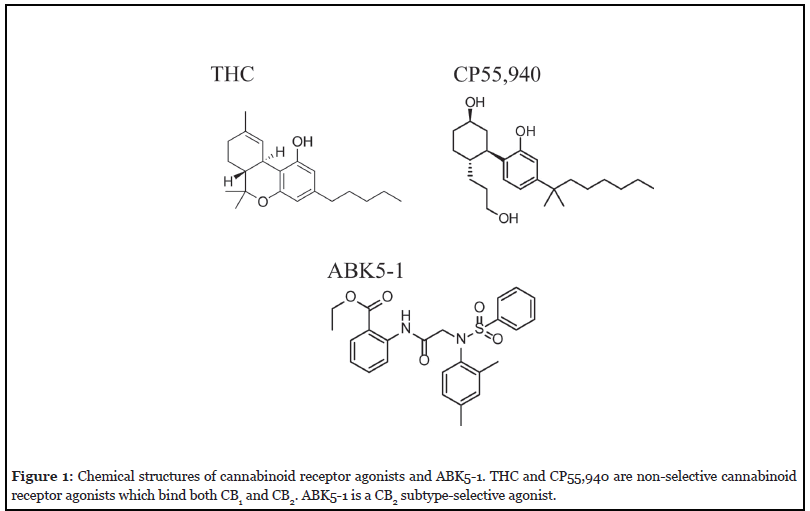

CB2 receptors are expressed in immune cells including microglia, and activation by CB2 agonists can reduce pro-inflammatory cytokine production in those cells [19-26]. Previously, we have reported that a CB2 subtypeselective agonist, ABK5, which is a compound with a distinct structure from the known CB2 agonists, has anti-inflammatory effects in T-cells. ABK5 inhibited IL-2 and TNF-α production and chemotaxis induced by CXCL12 [27,28]. To optimize ABK5 for better efficacy, we introduced several analogs of ABK5, and found ABK5-1 (Figure 1) had a good binding affinity to CB2 (Ki=28 nM) without CB1 binding. Similar to its lead compound, ABK5-1 also had anti-inflammatory effects, not only in T-cells but also in the microglial cell line BV-2. In this study, to further evaluate the impact of ABK5-1 on cytokine production in microglia, we globally analyzed the changes in the levels of many cytokines. In addition, the effect of ABK5-1 on some components of signal transduction was also analyzed as a possible mechanism of the anti-inflammatory effects.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

ABK5-1 was purchased from ChemBridge Corporation (San Diego, CA USA). Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) was obtained from Millipore Sigma (St. Louis, MO USA). Phospho-p44/42 MAPK (pERK) and p44/42 (ERK) rabbit monoclonal antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA USA). IRDye 680RD Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L) was purchased from LI-COR Biotechnology (Lincoln, NE USA).

Cell culture and drug treatment

BV-2 cells were cultured in Minimum Essential Medium (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2 saturation.

For ABK5-1 treatment, BV-2 cells were seeded at 1 × 105 cells/mL and allowed to grow for 24 hours. After 24 hours, cells were treated with 10 μM ABK5-1 or vehicle (DMSO) for 30 minutes in serum free Minimum Essential Medium and then stimulated with 1 μg/mL LPS for 24 hours. 500 μL of cell culture supernatant was collected and subjected to cytokine arrays using Proteome Profiler Mouse Cytokine Array Kit, Panel A (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN USA) following the manufacturer instructions. The signal was detected by a ChemiDoc MP Imaging System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA USA). Cells were collected for western blot analysis or mRNA analysis by real-time PCR.

Quantitative real-time PCR

BV-2 cells were lysed and total RNA was extracted using TRIzol Reagent (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA USA) followed by reverse transcription by a High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using an Applied Biosystems 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR system in a 10 μL reaction volume containing 2 μL diluted cDNA and 0.5 μM each of forward and reverse primers, and PowerUp SYBR Green Master Mix (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA USA). Primers used in the reaction are as follows: mouse 36B4 forward, 5’-ACTGGTCTAGGACCCGAGAAG-3’, and mouse 36B4 reverse, 5’-TCCCACCTTGTCTCCAGTCT-3’, and mouse CSF3 forward, 5’-CCCGAAGCTTCCTGCTTA -3’, and mouse CSF3 reverse, 5’-GGGGTGACACAGCTTG TAGG-3’, and mouse ICAM-1 forward, 5’-TTTGGGATGGT AGCTGGAAG-3’, mouse ICAM-1 reverse, 5’-TTTGGGATGG TAGCTGGAAG-3’, and mouse MCP-1 forward, 5’-CA TCCACGTGTTGGCTCA-3’, mouse MCP-1 reverse, 5’-GCTG CTGGTGATCCTCTTGT-3’, and mouse MIP-1a forward, 5’-TGCCCTTGCTGTTCTTCTCT-3’, mouse MIP-1a reverse, 5’-GATGAATTGGCGTGGAATCT-3’, and mouse RANTES forward, 5’-TGCAGAGGACTCTGAGACAGC-3’, mouse RANTES reverse, 5’-CCATATGGTGAGGCAGGTG-3’. The PCR cycles are as follows: 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 2 min, 40 cycles of 95°C for 3 sec and 60°C for 30 sec.

Western blotting

BV-2 cells were harvested and lysed in lysis buffer 6 (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN USA) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA USA) on ice for 30 minutes. The cell lysates were then treated with β-mercaptoethanol and 15 μg of protein was loaded to each well of polyacrylamide gels, and subjected to electrophoresis. Proteins in the gels were transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane (MilliporeSigma; Burlington, MA USA) and blocked with Superblock T20 (PBS) blocking reagent (Fisher Scientific; Pittsburgh, PA, USA) overnight, followed by incubation with primary antibodies (pERK and ERK) for 2 hr and secondary antibodies (IRDye goat anti-rabbit IgG) for 1 hr at room temperature. Bands were detected by the Odyssey CLx imaging system (LI-COR Biotechnology, Lincoln, NE USA).

Data analysis

Results are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (S.E.M.). Signals of dot blots were quantified by pixel density using ImageJ. Western blot bands were quantified by intensity of fluorescence by Image Studio (LI-COR Biotechnology, Lincoln, NE USA). One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test was used to determine significant differences from the control group.

Results

Cytokine screening in microglia

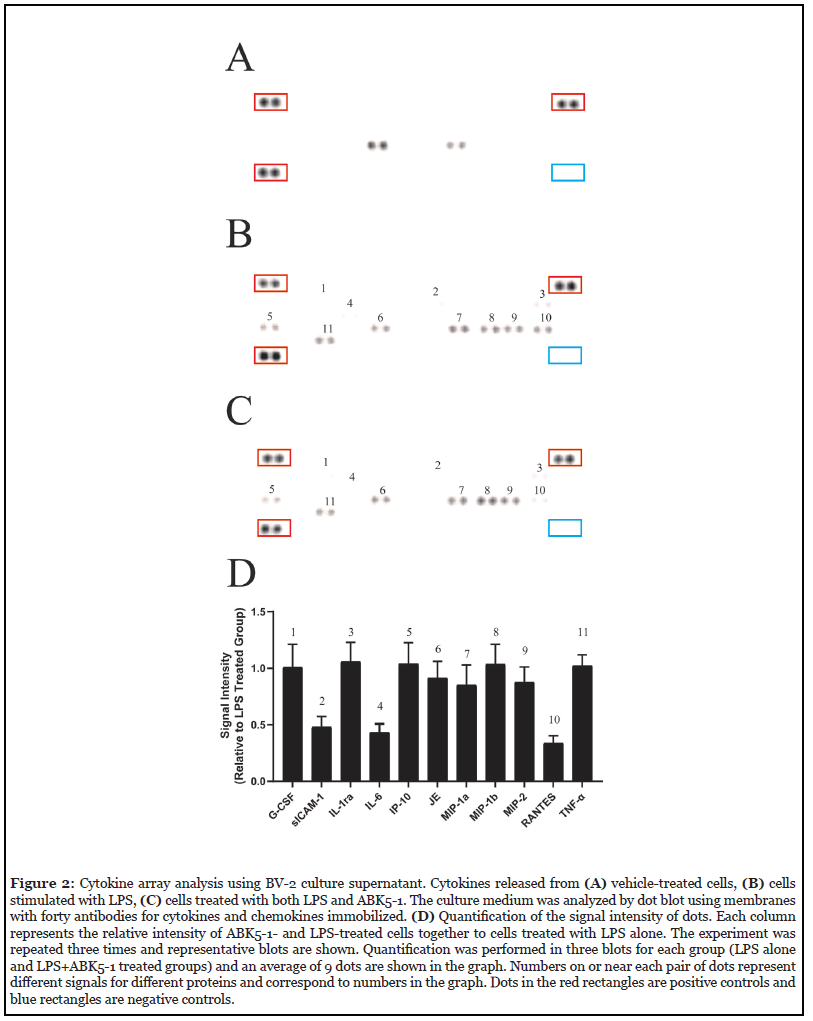

Activation of the CB2 receptor is known to be associated with a decreased production of various pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α. [26,29-31]. To best characterize anti-inflammatory effects of our compound ABK5-1, we screened for changes in the levels of various cytokines and chemokines after LPS stimulation and LPS stimulation plus ABK5-1 treatment in BV-2 mouse microglia cell line. Dot blot analysis was performed using membranes with forty antibodies for cytokines and chemokines immobilized and the cell culture supernatant from BV-2 cells was treated with vehicle (Figure 2A), LPS (Figure 1B), and both LPS and ABK5-1 (Figure 1C). Eleven cytokines and chemokines in total were detected after 24 hr stimulation with LPS, and compared with vehicle treated cells, nine were increased by LPS treatment (Figures 2A and 2B). IL-1β, which is known to be induced by LPS stimulation in BV-2 cells was not detected under the current conditions. We then analyzed the effect of ABK5-1 on these eleven cytokines and chemokines which could be detected in LPS treated cells to evaluate if ABK5-1 decreased the cytokine levels increased by LPS stimulation. ABK5-1 treatment in LPS-stimulated cells decreased three total cytokines and chemokines. They are soluble intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (sICAM1), IL-6, and regulated upon activation, normal T cell expressed and pesumably secreted (RANTES) and the level was decreased more than 50% compared with cells stimulated with LPS alone (Figures 2B-2D). In addition, monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP-1), macrophage inflammatory proteins (MIP)-1α, and MIP-2 also showed a decreasing tendency by ABK5-1 treatment. In contrast, although reported to be inhibited by CB2 activation, LPS-induced TNF-α in the culture medium did not change by ABK5-1 treatment. ABK5-1 did not affect cell viability (data not shown).

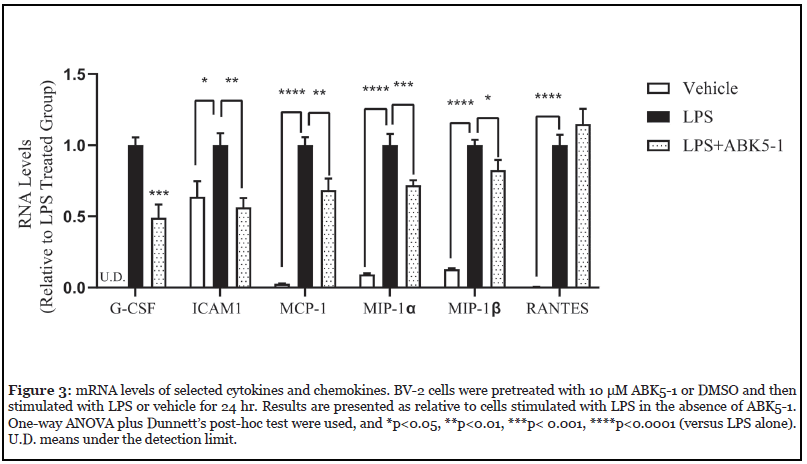

Effects of ABK5-1 on cytokine mRNA levels

To confirm the change of cytokines by ABK5-1, mRNA levels of selected cytokines and chemokines were evaluated by RT-PCR (Figure 3). All six mRNAs of cytokines and chemokines were induced by 24 hr LPS treatment. Although protein level of Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) decrease was not observed in cytokine array, ABK5-1 treatment significantly decreased mRNA level by 51% compared with cells treated with LPS alone. The mRNA level of ICAM1, which is the gene of sICAM-1, decreased by 44% by ABK5-1 treatment and this was similar to the level before LPS treatment. Three chemokines, MCP-1, MIP-1α, and MIP-1β mRNA levels also significantly decreased by 31%, 28%, and 17%, respectively. These results support the effect of ABK5-1 on cytokine and chemokine production in BV-2 cells. In contrast, interestingly, mRNA level for RANTES did not change by ABK5-1 treatment despite more than 50% decrease was observed in protein level in cell culture medium (Figure 2D).

Analysis of ERK phosphorylation

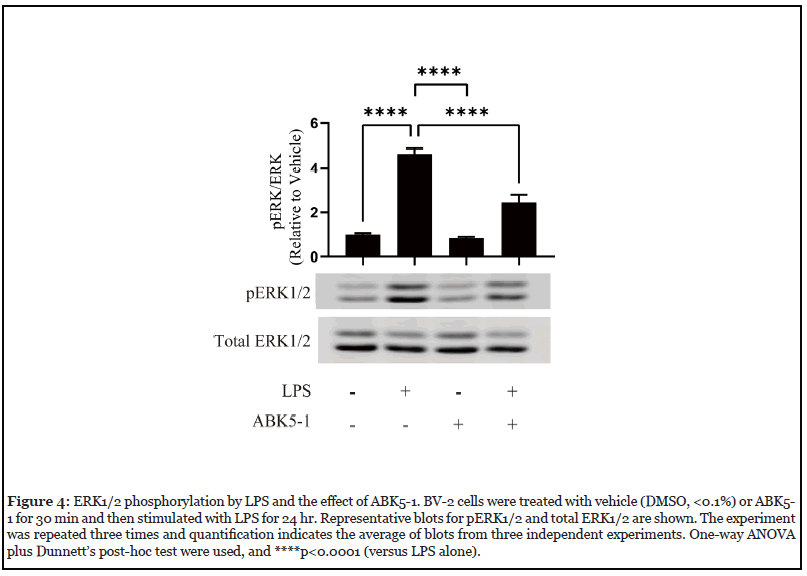

LPS binds to the toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 and promotes production of cytokines through a number of different signaling pathways including MAPK pathways. CB2 activation by cannabinoid receptor agonists such as anandamide, WIN 55,212-2, and JWH-015 have been reported to inhibit ERK1/2 phosphorylation in microglia and decreased the production of inflammatory mediators [22,24]. To examine if ABK5-1 also has a similar effect, we evaluated ERK1/2 phosphorylation in BV-2 cells treated with LPS, ABK5-1, and both LPS and ABK5-1. After 24 hr of incubation, LPS significantly increased ERK1/2 phosphorylation while ABK5-1 did not change ERK1/2 phosphorylation (Figure 4). Co-incubation of LPS and ABK5-1 resulted in significant decreases of phospho- ERK1/2 level relative to cells treated with LPS alone (Figure 4). This suggests that the effect of ABK5-1 on cytokine production may also be associated with a decrease of ERK1/2 phosphorylation.

Discussion

Inhibiting neuroinflammation through targeting microglia is considered to be a good strategy for finding new therapeutics for various diseases including neurodegenerative disorders and chronic pain. Chronic pain has been a major health concern because it severely affects people’s quality of life, and also there is a lack of safe and effective drugs for treatment of high-impact chronic pain which may lead to the public health issue (e.g. the opioid crisis). Neuropathic pain is one of the major types of chronic pain, and activation of microglia by inflammatory mediators released from damaged nerves is known to be involved [13,14]. Since activated microglia further produce a variety of inflammatory mediators which change excitability of neurons and cause pain [13,15] reduction of pro-inflammatory cytokine production in microglia is a first step in targeting microglia to reduce pain.

Cannabinoids are known to have anti-inflammatory effects and activation of CB2 receptor is considered to be responsible for these effects [32]. In contrast to the CB1 receptor which is mainly localized in neurons, the CB2 receptor is primarily expressed by immune cells such as macrophages, T cells, and microglia [6,7]. Since selective activation of CB2 does not cause psychoactive effects [8,11], CB2 subtype selective agonists are good drug candidates for reducing neuroinflammation and associated pain. We have previously reported that a CB2 subtype selective agonist ABK5, which has a distinct structure from known cannabinoid receptor agonists, inhibits inflammation in human T cells [28]. ABK5-1 is an ABK5 analog which is also a subtype selective CB2 agonist with marginally stronger anti-inflammatory effects than the lead compound. Since this compound also inhibited production of IL-1β and IL-6 in microglia, we were interested in what other inflammatory mediators it can modulate and the possible signaling pathway that was involved in the effects.

LPS stimulation induced nine cytokines and chemokines in BV-2 cells. Induction of IL-6 was observed and the level of IL-6 decreased by ABK5-1 treatment (Figure 2). This was compatible with our previous observation in RT-PCR and ELISA, in which ABK5-1 significantly decreased IL-6 mRNA and protein levels. In contrast, IL-1β, which is a cytokine that is known to be induced by LPS in microglia, was not detected in the cytokine array using cell culture medium. We have previously observed an increase of IL-1β mRNA in BV-2 cells by LPS stimulation, but IL-1β protein concentration in the culture medium was much lower than that of IL-6. Therefore, IL-1β concentration in the culture medium might be under the detection limit of the current method. Cannabinoid receptor agonists have been reported to decrease TNF-α in primary microglia and N9 microglia cell lines [29]. Although TNF-α was induced by LPS in the present study, ABK5-1 treatment did not show an inhibitory effect on TNF-α release to cell culture medium. This can be a limitation of BV-2 cells, or can be also be a compound-dependent observation. Some CB1 receptor agonists are known to cause biased signaling in which only certain signaling pathways are activated depending on which agonist is used [33]. Considering the complexity of the signaling pathway downstream of the TLR4 and the CB2 receptor, ABK5-1 may only activate certain pathways which are involved in regulation of IL- 1β and IL-6, but not TNF-α. It would be interesting to perform a phospho-protein array in primary microglia and compare with compounds which are known to inhibit TNF-α production in the future.

To support the anti-inflammatory effect of ABK5-1 which was evaluated by cytokine array analysis, we also checked mRNA levels of selected cytokines and chemokines in cells stimulated with LPS with and without ABK5-1. Although the change of mRNA levels for most genes were compatible with the change in protein levels observed in the cytokine array analysis, G-CSF and RANTES were the exceptions. G-CSF only decreased in the mRNA level but not in the protein level, while RANTES only changed in the protein level but not the mRNA level. Since mRNA changes are faster than changes in the protein level, doing time course analysis might be helpful to further analyze the change of these two inflammatory mediators. In addition, ABK5-1 may also change the expression of these proteins through modulating post-transcriptional regulation. Further study is needed to clarify the mechanism of this difference between mRNA and protein levels.

Although some studies showed an increase of antiinflammatory cytokines such as IL-4 and IL-10 after activation of CB2 by various methods [26,29,34-36], we did not observe increase of such cytokines in the current condition. This might be due to the difference between different cell lines and primary microglia and the difference of the stimulation method. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that a lack of effect on anti-inflammatory cytokines is compound dependent and our compound does not cause an increase of anti-inflammatory cytokines, since certain compounds seem to increase IL-10 by CB2 agonist in BV-2 cells [36]. Considering anti-inflammatory cytokines are produced by a different population of microglia which have undergone alternative activation, it will be interesting to compare the change of microglial phenotype between known CB2 agonists and ABK5-1.

The endocannabinoid, anandamide, and some other cannabinoid receptor agonists are known to inhibit LPSmediated ERK1/2 phosphorylation and consequent transcription of inflammatory mediators in microglia [22,24]. Consistent with these findings, ABK5-1 also inhibited LPS-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation in BV-2 cells. This change may also be associated with a decrease of cytokine by ABK5-1. However, there are more signaling molecules, such as p38 and Akt pathways, which may also play roles in LPS-mediated cytokine production. Since cannabinoid receptor activation also modulates these pathways, ERK1/2 may not be the only mechanism for the anti-inflammatory effects of ABK5-1. Future studies will include broader evaluation of signaling pathways involved in anti-inflammation and the effect of ABK5-1 on it.

In conclusion, we have analyzed LPS-induced cytokines and chemokines inhibited by the CB2 subtype selective agonist ABK5-1, and found three cytokines and chemokines were affected by the compound. Change of the inflammatory mediators were also supported by measuring individual mRNA levels. This may be associated with inhibition of ERK1/2 phosphorylation. These observations support that ABK5-1 has anti-neuroinflammation effects.

Future Research Directions

Since the present study was mainly conducted in BV-2 cells, which may not completely reflect reactions of microglia in the body, it will be interesting to evaluate cytokine production (especially anti-inflammatory cytokines) and activation markers after ABK5-1 treatment in primary microglia isolated from rodents. Testing if ABK5-1 can pass the blood-brain barrier will be essential before performing animal studies to determine if the compound can be effective in neuropathic pain model animals. Finally, performing a behavioral test to evaluate if the compound can cause psychoactive effects in rodents and testing the analgesic effects in neuropathic pain models will provide strong evidence that this compound is a good drug candidate for treating neuropathic pain.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare there are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We thank to Dr. José Manautou (University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT) for his plate reader and Dr. Xiaobo Zhong (University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT) for the ChemiDoc MP Imaging System. This work was supported, in part, by National institutes of Health grant DA040920 (to D.A. Kendall).

Author Contributions

Participated in research design: Tang, Wolk, Kendall.

Conducted experiments: Tang, Wolk.

Performed data analysis: Tang, Wolk, Kendall.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Tang, Kendall.

References

2. Pertwee RG, Howlett AC, Abood ME, Alexander SP, Di Marzo V, Elphick MR, et al. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXIX. Cannabinoid receptors and their ligands: beyond CB(1) and CB(2). Pharmacol Rev. 2010;62(4):588-631.

3. Matsuda LA, Lolait SJ, Brownstein MJ, Young AC, Bonner TI. Structure of a cannabinoid receptor and functional expression of the cloned DNA. Nature. 1990;346(6284):561-4.

4. Busquets-Garcia A, Bains J, Marsicano G. CB(1) Receptor Signaling in the Brain: Extracting Specificity from Ubiquity. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2018;43(1):4-20.

5. Pertwee RG. Emerging strategies for exploiting cannabinoid receptor agonists as medicines. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;156(3):397-411.

6. Munro S, Thomas KL, Abu-Shaar M. Molecular characterization of a peripheral receptor for cannabinoids. Nature. 1993;365(6441):61-5.

7. Galiègue S, Mary S, Marchand J, Dussossoy D, Carrière D, Carayon P, et al. Expression of central and peripheral cannabinoid receptors in human immune tissues and leukocyte subpopulations. Eur J Biochem. 1995;232(1):54- 61.

8. Malan TP, Jr., Ibrahim MM, Deng H, Liu Q, Mata HP, Vanderah T, et al. CB2 cannabinoid receptor-mediated peripheral antinociception. Pain. 2001;93(3):239-45.

9. Malan TP, Ibrahim MM, Lai J, Vanderah TW, Makriyannis A, Porreca F. CB2 cannabinoid receptor agonists: pain relief without psychoactive effects? Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2003;3(1):62-7.

10. Deng L, Guindon J, Cornett BL, Makriyannis A, Mackie K, Hohmann AG. Chronic cannabinoid receptor 2 activation reverses paclitaxel neuropathy without tolerance or cannabinoid receptor 1-dependent withdrawal. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;77(5):475-87.

11. Chen D-j, Gao M, Gao F-f, Su Q-x, Wu J. Brain cannabinoid receptor 2: expression, function and modulation. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 2017;38(3):312- 6.

12. Li Q, Barres BA. Microglia and macrophages in brain homeostasis and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2018;18(4):225-42.

13. Chen G, Zhang Y-Q, Qadri YJ, Serhan CN, Ji R-R. Microglia in Pain: Detrimental and Protective Roles in Pathogenesis and Resolution of Pain. Neuron. 2018;100(6):1292-311.

14. Tsuda M. Microglia in the CNS and Neuropathic Pain. In: Shyu B-C, Tominaga M, editors. Advances in Pain Research: Mechanisms and Modulation of Chronic Pain. Singapore: Springer Singapore; 2018. p. 77-91.

15. Ji R-R, Chamessian A, Zhang Y-Q. Pain regulation by non-neuronal cells and inflammation. Science. 2016;354(6312):572.

16. Kidd BL, Urban LA. Mechanisms of inflammatory pain. Br J Anaesth. 2001;87(1):3-11.

17. Baral P, Udit S, Chiu IM. Pain and immunity: implications for host defence. Nat Rev Immunol. 2019;19(7):433-47.

18. Gonçalves dos Santos G, Delay L, Yaksh TL, Corr M. Neuraxial Cytokines in Pain States. Front Immunol. 2020;10(3061).

19. Berdyshev EV, Boichot E, Germain N, Allain N, Anger JP, Lagente V. Influence of fatty acid ethanolamides and delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol on cytokine and arachidonate release by mononuclear cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 1997;330(2-3):231-40.

20. Ross RA, Brockie HC, Pertwee RG. Inhibition of nitric oxide production in RAW264.7 macrophages by cannabinoids and palmitoylethanolamide. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;401(2):121-30.

21. Yuan M, Kiertscher SM, Cheng Q, Zoumalan R, Tashkin DP, Roth MD. Delta 9-Tetrahydrocannabinol regulates Th1/Th2 cytokine balance in activated human T cells. J Neuroimmunol. 2002;133(1-2):124-31.

22. Eljaschewitsch E, Witting A, Mawrin C, Lee T, Schmidt PM, Wolf S, et al. The endocannabinoid anandamide protects neurons during CNS inflammation by induction of MKP-1 in microglial cells. Neuron. 2006;49(1):67-79.

23. Borner C, Smida M, Hollt V, Schraven B, Kraus J. Cannabinoid receptor type 1- and 2-mediated increase in cyclic AMP inhibits T cell receptor-triggered signaling. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(51):35450-60.

24. Romero-Sandoval EA, Horvath R, Landry RP, DeLeo JA. Cannabinoid receptor type 2 activation induces a microglial anti-inflammatory phenotype and reduces migration via MKP induction and ERK dephosphorylation. Mol Pain. 2009;5:25.

25. Cencioni MT, Chiurchiu V, Catanzaro G, Borsellino G, Bernardi G, Battistini L, et al. Anandamide suppresses proliferation and cytokine release from primary human T-lymphocytes mainly via CB2 receptors. PLoS One. 2010;5(1):e8688.

26. Hernangómez M, Mestre L, Correa FG, Loría F, Mecha M, Iñigo PM, et al. CD200-CD200R1 interaction contributes to neuroprotective effects of anandamide on experimentally induced inflammation. Glia. 2012;60(9):1437-50.

27. Scott CE, Tang Y, Alt A, Burford NT, Gerritz SW, Ogawa LM, et al. Identification and biochemical analyses of selective CB2 agonists. Eur J Pharmacol. 2019;854:1-8.

28. Tang Y, Wolk B, Britch SC, Craft RM, Kendall DA. Anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive effects of the selective cannabinoid CB2 receptor agonist ABK5. J Pharmacol Sci. 2020.

29. Ma L, Jia J, Liu X, Bai F, Wang Q, Xiong L. Activation of murine microglial N9 cells is attenuated through cannabinoid receptor CB2 signaling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;458(1):92-7.

30. Malek N, Popiolek-Barczyk K, Mika J, Przewlocka B, Starowicz K. Anandamide, Acting via CB2 Receptors, Alleviates LPS-Induced Neuroinflammation in Rat Primary Microglial Cultures. Neural Plast. 2015;2015:130639.

31. Ehrhart J, Obregon D, Mori T, Hou H, Sun N, Bai Y, et al. Stimulation of cannabinoid receptor 2 (CB2) suppresses microglial activation. J Neuroinflammation. 2005;2:29.

32. Dhopeshwarkar A, Mackie K. CB2 Cannabinoid receptors as a therapeutic target-what does the future hold? Mol Pharmacol. 2014;86(4):430-7.

33. Al-Zoubi R, Morales P, Reggio PH. Structural Insights into CB1 Receptor Biased Signaling. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(8):1837.

34. Askari VR, Shafiee-Nick R. The protective effects of β-caryophyllene on LPS-induced primary microglia M1/M2 imbalance: A mechanistic evaluation. Life Sci. 2019;219:40-73.

35. Tao Y, Li L, Jiang B, Feng Z, Yang L, Tang J, et al. Cannabinoid receptor-2 stimulation suppresses neuroinflammation by regulating microglial M1/M2 polarization through the cAMP/PKA pathway in an experimental GMH rat model. Brain Behav Immun. 2016;58:118-29.

36. McDougle DR, Watson JE, Abdeen AA, Adili R, Caputo MP, Krapf JE, et al. Anti-inflammatory ω-3 endocannabinoid epoxides. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(30):E6034.