Commentary

Insects conform large numbers of parasites and pathogens in diverse habitats. Cuticular structures on their body surfaces and secreted membranes in their digestive tracts are the first defensive barriers to prevent entry of invading organisms [1]. Across the extended range of genera and species, insects acquired common first front defensive mechanisms. These include hemolymph molecules that form clots and melanin deposits or recruit hemocytes that phagocytose, encapsule or form nodules that surround pathogens [2–4] that after successfully breach these barriers, invade the insect body [5].

Humoral responses comprise constitutive primary mechanisms, including lectins, and melanin through the prophenoloxidase (PPO) cascade [6–8], nitric oxide (NO), oxygen-reactive species (ROS) and antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), that are released to the hemolymph to combat invasive pathogens.

Most of the knowledge about the immune pathways in insects has been obtained from dipterans (mainly Drosophila melanogaster and mosquitoes) and coleopterans (beetles) [9–11]. This research has facilitated the organization of insect immunity into key signaling cascades, (Toll, JAK-STAT, and IMD) [12].

Antimicrobial peptides are mainly produced in the fat body, midgut, and hemocytes [13]. This production is organized in two main molecular cascades, the immune deficiency (IMD) [14] and Toll pathways. The IMD pathway is analogous to the tumor-necrosis-receptor factor (TNFR) pathway in mammals. Toll involves molecules with parallels to mammalian signaling cascades such as the interleukin-1 receptor (IL-1R) and Toll-like receptors (TLRs). A third pathway, the JAK/STAT (Janus Kinase) activates transcription signal transducers [15] and contributes to humoral immune responses through the production of peptides with thio-ester residues (Tep) and totA. These have important functions in hemopoiesis and the regulation of hemocyte proliferation [15]. In Drosophila, Upd-3 cytokines contribute to the integration of the immune response by orchestrating the fat body, hemocytes, and lymphatic gland (hemopoiesis site) [15].

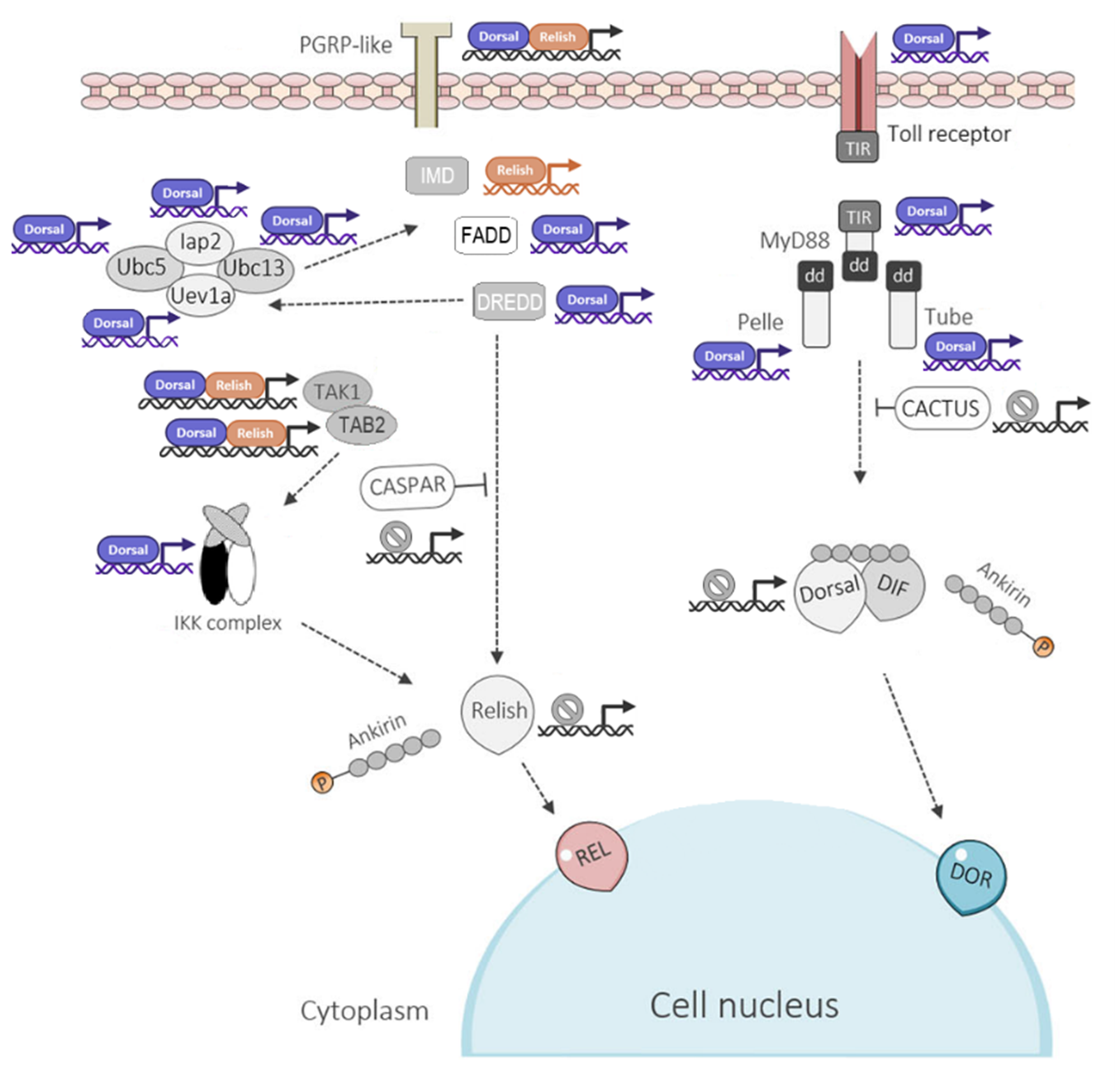

The IMD pathway is primarily activated by Gram negative bacteria [2,14,16], as it recognizes a specific component of their cell walls. It is activated when the diaminopimelic acid-type peptidoglycan (DAP-PGN) common in most Gram-negative bacteria and Bacillus [15,17,18] binds to and activates transmembrane pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), namely peptidoglycan recognition proteins (PGRPs) (Figure 1). Activated PGRP receptors, interacts with the death domain of the IMD adaptor and the Fas- associated death domain (dFADD [19,20]. Then, FADD recruits death-related ced-3/Nedd2-like caspase (DREDD) [21], dTak1 (transforming growth factor ?-activated kinase-1) and dTab2 (dTak1 binding protein) [22]. The dimer dTak1 and dTab2 phosphorylates the Kenny-Ird5 kinase complex (IKK) [22,23]. Which in turn phosphorylates Relish (a member of the NF-κB transcription family). In this complex, DREDD is responsible for cleaving Relish, whose N-terminal fragment moves into the nucleus and induces the transcription of immune genes such as Cecropins, attacins, diptericins, drosomycin, and metchnicowin [24,25].

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the IMD and Toll signaling pathways in Rhodnius prolixus. The diagram shows the main components of both pathways and highlights the predicted Relish and Dorsal/Dif transcription factor binding sites within the promoter regions of their target genes. Promoter sequences, defined as the 2,000 bp upstream of each gene’s transcription start site, were extracted from VectorBase (https://vectorbase.org/vectorbase/). Binding motifs for Relish and Dorsal/Dif were obtained from the JASPAR CORE database (https://jaspar.elixir.no/) and used to scan promoter regions, applying a relative score threshold >0.8 to identify high-confidence binding sites. Abbreviations: PGRP: Peptidoglycan Recognition Protein; FADD: Fas-Associated Death Domain protein; DREDD: Death-Related Ced-3/Nedd2-like Caspase; IAP2: Inhibitor of Apoptosis Protein 2; Ubc5: Ubiquitin-Conjugating Enzyme 5; Ubc13: Ubiquitin-Conjugating Enzyme 13; Uev1a: Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 variant 1a; TAK1: Transforming Growth Factor-β-Activated Kinase 1; TAB2: TAK1-Binding Protein 2; Caspar: Cytoplasmic inhibitor of Relish activation; Toll: Toll receptor; MyD88: Myeloid Differentiation Primary Response Protein 88; Tube: Tube adaptor protein; Pelle: Pelle serine/threonine-protein kinase; Cactus: inhibitor of Dorsal/Dif nuclear translocation.

The Toll pathway is activated when extracellular receptors recognize lysine-containing peptidoglycan (Lys-PGN) and β-1,3-glucan present, PAMPs of the cell walls of Gram-positive bacteria and fungi (Figure 1). This activates a serine protease cascade (MSP) [26,27] (SPE) that cleaves pro-Spätzle (Spz). Spätzle binds to the Toll receptor on the cell membrane, and this complex triggers a cytoplasmic cascade via MyD88-Tube-Pelle complex. Pelle phosphorylates and degrades Cactus The processed Cactus releases Dorsal and Dorsal-related immune factors (Dif) (both of NF-κB family transcription factors). These are translocated to the nucleus where they induce the expression of AMPs like Drosomycin, defensin 2 and Mechnikowin [28] (Figure 1).

The genes coding fundamental innate immune responses and the production of AMPS have been found in most annotated insect genomes [9]. Although some components of the Toll cascade are missing, it is consensus that Toll is functional in all of them, including hemipterans [10,11,29–31]. In this hemimetabolous insect order, annotated genome and transcriptomic data revealed that the composition of the IMD cascade varies among its member groups [32,33]. In one extreme, the Imd gene and most of the IMD pathway are present in members of the Auchenorrhyncha group [34–36]; and in the other extreme, members of the Sternorrhyncha are devoided of almost the entire IMD cascade [37], but were documented in the reduviid Rhodnius prolixus, the stink bug Plautia stali, and other species [38–40]. The Imd sequence of P. stali with very low homology with the canonical sequences of dipterans, was proven functional [32], and using this sequence as a query, Imd-like sequences functioning in AMP transcription were identified in other heteropterans Cimex lectularius and Halyomorpha Halys [41]. Highlighting the limitations of the identification of highly variable genes solely based on their similarities with canonical nucleotide sequences from dipterans.

Whitin heteropterans, triatomines are a group of important vectors of Chagas disease that feed exclusively on vertebrate blood. We previously investigated innate immune response genes of this group, in transcriptomes of blood-fed uninfected Triatoma infestans, T. dimidiata and T. pallidipennis, using the genome of R. prolixus as data reference [42]. Among the most relevant findings, we identified gene homologs to constitutive primary effector components such as PPO serine proteases with CLIP domain that are known to participate in the activation of PPO and the Toll pathway in other insects. Also, homologue genes for PLCβ and NADPH enzymes, confirmed the participation of ROS and NO in antibacterial responses in triatomines [43,44] and the production of AMPs [45–47].

The components of the Toll and JAK-STAT were documented in the three triatomines, but not the IMD canonical components Imd, FADD, and DREED. These observations were consistent with previous observations in the R. prolixus (RPRO), C. lectularius (CLEC) and A. pisum (ACPI) genomes [39,47,48] and other hemipterans [34,35,49–51], Phthirapteran [52] and chelicerates [52,53]. Thus, we proposed that the absence of canonical components of the IMD pathway was common among hemimetabolous arthropods [42]. However, in further analysis, we retrieved annotated Imd protein sequences from Cimex lectularius, Nilaparvata lugens, and Sogatella furcifera from the 4IN (Innate Immunity Genes in Insects) databases. We used these sequences as queries in tBLASTn searches against the genome assemblies of Rhodnius prolixus and Triatoma infestans in the NCBI database, and against a new assembled transcriptome of T. pallidipennis-infected with T. cruzi.

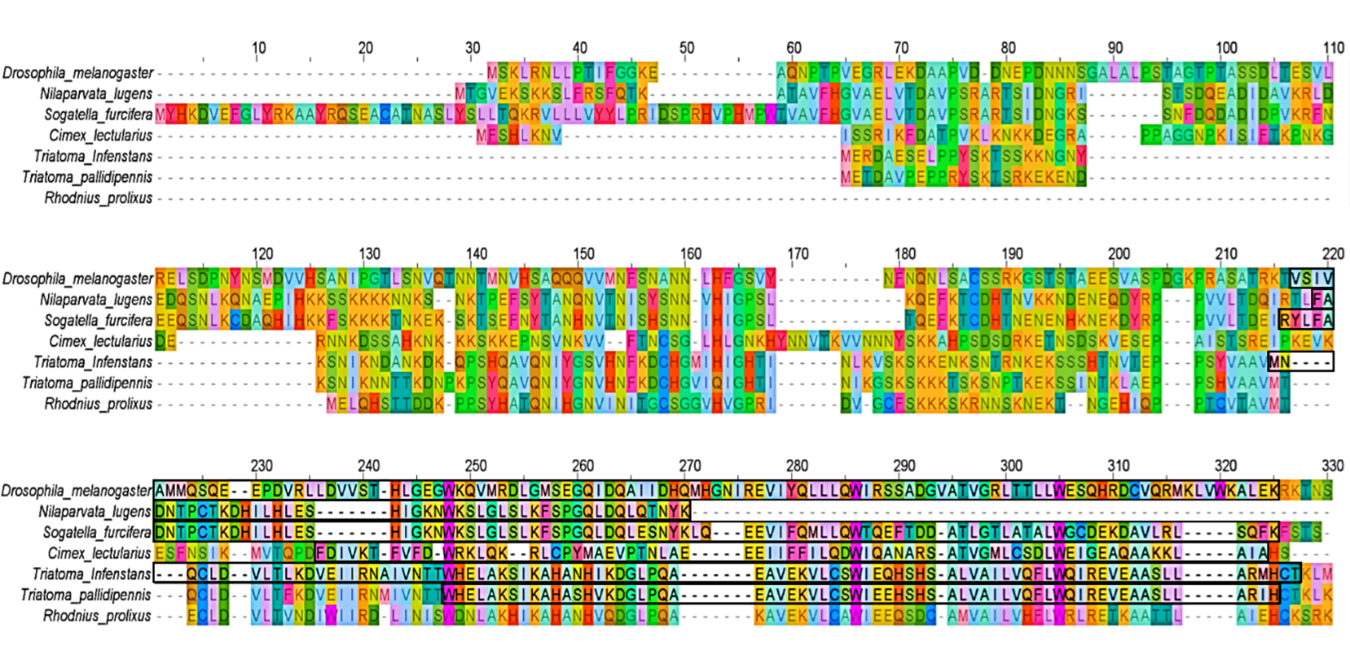

In this exercise, putative Imd and Imd-like protein sequences, along with those corresponding to other key components of the IMD pathway FADD, DREDD, IAP2, Effete, TAK1, TAB2, Caspar, and Relish were identified in the six hemipteran species, including T. pallidipennis. These sequences were then subjected to comparative analysis using multiple sequence alignments with D. melanogaster orthologs revealed extensive divergence in the Imd proteins, particularly in the N-terminal region, where high variability in length and composition hindered reliable alignment. In contrast, partial alignment was possible in the C-terminal region, which commonly featured a conserved Death domain. However, this domain also showed substantial variability, with only a few residues conserved across species, which could have difficulted their identification in previous searches. Subsequent protein Domain annotation (using conserved domain database InterPro, available at: https://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/) confirmed the presence of the Death domain (IPR000488) in most Imd-like sequences, with the notable exception of R. prolixus, where no recognizable Death domain was found, suggesting either a loss of this signaling motif or high sequence divergence (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Multiple sequence alignment of Imd protein sequences from six hemipteran species: Nilaparvata lugens, Sogatella furcifera, Cimex lectularius, Triatoma infestans, Triatoma pallidipennis, and Rhodnius prolixus. Sequences were obtained through tBLASTn (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) searches using annotated Imd proteins from the 4IN database (Innate Immunity Genes in Insects, available at: http://bf2i300.insa-lyon.fr:443/home) as queries and aligned with the canonical Imd sequence from Drosophila melanogaster. Conserved regions corresponding to the Death domain were identified using InterPro (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/) and are highlighted with black rectangles. The R. prolixus sequence lacks a detectable Death domain, indicating potential divergence or functional loss of this domain in this species..

Pairwise amino acid sequence identity between D. melanogaster and the hemipteran Imd-like proteins was low: 15.4% (42/273) for N. lugens, 23.1% (63/273) for S. furcifera, 20.5% (56/273) for C. lectularius, 13.2% (36/273) for T. infestans, 11.7% (32/273) for T. pallidipennis, and 12.5% (34/273) for R. prolixus. In contrast, higher identity values were observed among species of the same family. For instance, T. infestans and T. pallidipennis (Reduviidae) shared 78.2% identity (154/197), while R. prolixus was more divergent, with 43.4% identity (85/196) with T. infestans, and 48.7% (96/197) with T. pallidipennis.

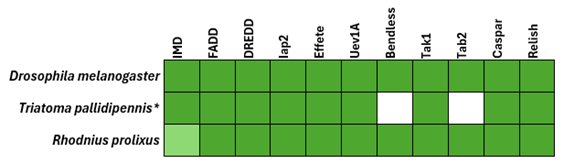

All queried IMD pathway components were successfully identified in R. prolixus, suggesting the presence of a complete and potentially functional pathway. In T. pallidipennis, transcripts corresponding to most components were also detected, except for Bendless and TAB2 (Figure 3). This absence may reflect species-specific gene loss, condition-dependent expression, or limitations of the transcriptome assembly. These findings highlight both the conservation and diversification of the IMD signaling pathway among hemipterans, emphasizing the need for integrative approaches to characterize immune pathways in non-model insects.

Figure 3. Comparative identification of IMD pathway components in Rhodnius prolixus and Triatoma pallidipennis. Protein sequences of IMD pathway components (Imd, FADD, DREDD, IAP2, Effete, TAK1, TAB2, Caspar, and Relish) were obtained from the 4IN database : (http://bf2i300.insa-lyon.fr:443/home) and used as queries in tBLASTn (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) searches against the genome assembly of R. prolixus and a de novo assembled transcriptome of T. pallidipennis. Drosophila melanogaster is included as a model organism of the IMD signaling pathway to contextualize the findings in hemipteran insects. Presence of genes or transcripts is indicated in dark green; light green indicates the presence of the gene but lacking the representative domain (Death domain, IPR000488). An asterisk (*) denotes that a transcriptome was used as a reference instead of an annotated genome.

The functionality of the IMD pathway and how insects with incomplete or total absence of the IMD pathway cope with bacterial infections are still under scrutiny. In Drosophila and other insects, the IMD pathway responds to Gram negative bacteria, and it is proposed that it evolved to control the digestive tract microbiota. However, PGRPS, IMD, dFADD, ird5 and relish genes have not been found in the aphid A. pisum [47], indicating a complete absence of IMD responses. It was proposed that because of the feeding on sterile plant juices, these insects have no need to expend resources for controlling meal-ingested microbes. On the other hand, the absence of AMPs, may favor the colonization of other useful bacterial symbionts that provide necessary elements absent in plant juices [36] and protection against fungal infections and parasitoids. Altogether, these advantages provided by Gram negative bacteria could have propitiated the evolutive elimination of the IMD pathway in aphids [36].

The specificity and independence between insect Toll and IMD pathways are challenged by observations in Drosophila responding with Drosomycin upon activation of either Toll or IMD [54,55], and in Tribolium castaneum responding to challenges with either Gram positive and Gram-negative with a simultaneous activation of IMD and Toll pathways [56]. In the same context, in the hemipterans P. stali, Gram positive and Gram-negative bacteria induced preferentially Toll and IMD pathways, respectively [32], but silencing the Toll pathway reduced the expression of components of both pathways, suggesting a crosstalk between the two pathways. We documented similar responses in T. pallidipennis [57]. In this reduviid, the Toll-IMD functional interaction resulted in preferential induction of either pathway by Gram positive or Gram-negative bacteria, but a low cross induction of the other pathway was observed. In addition, an enhanced response to a second bacterial encounter with either pathogen (priming) followed the same cross induction pattern [58]. The molecular mechanisms of priming, the insect counterpart of immune memory in vertebrates [59,60], are still under investigation, but an induction of the interaction between Toll and IMD should be investigated.

The molecular mechanisms of Toll-IMD crosstalk awaits clarification. In Drosophila, a direct interaction between components of both cascades has been proposed; for instance, MyD88 possessing a death domain could bypass imd and activate the IMD cascade [61]. The induction of PAMs by the NF-κB transcription factors Relish and Dif was investigated in transfected cell lines. In these preparations, the homodimer Relish/ Relish was the best inducer of attacin expression, Relish/Dif and Reish/Dorsal heterodimers were better inducers of drosomycin and defensin expression [62]. Indicating that either alone or in combination, NF-κB transcription regulators could activate both IMD and Toll signaling pathways.

We performed an in silico analysis to predict putative binding sites for NF-κB transcription factors within the promoter regions, (defined as the 2,000 bp sequence upstream of the transcription starting site) of the IMD and Toll pathway genes of R. prolixus. This analysis involved scanning the R. prolixus genome assembly (VectorBase, RproC3) using the JASPAR 2022 database core collection (available at: https://jaspar.elixir.no/) for insect transcription factor binding motifs (relative score threshold > 80%). In the IMD pathway, predicted binding sites for Dorsal/Dif were identified in the promoter regions of the PGRP, FADD, DREDD, DIAP2, Ubc5, Ubc13, Uevla, TAK1, and TAB2 genes, while binding sites for Relish were present only in the PGRP, IMD, TAK1, and TAB2 genes. In the Toll pathway, Dorsal/Dif binding sites were identified in the genes encoding the Toll receptor, MyD88, Pelle, and Tube, with no detected binding sites for Relish. Notably, the promoters of the Caspar and Cactus genes (IMD and Toll pathway negative regulators, respectively), as well as the Relish and Dorsal/Dif genes themselves, lacked significant binding sites for either transcription factor (Figure 1). The high prevalence of Dorsal/Dif binding sites suggests that the transcriptional regulation of both immune pathways may be predominantly governed by the activation of the Toll pathway. These findings document the mechanism of cross activation of both pathways could be mediated by the transcription promoters.

In conclusion, the functionality of the IMD pathway in hemipterans should be understood bearing in mind the possibility that unidentified IMD cascade elements could still be present as such or substituted by other molecules or alternative signaling strategies that bypass canonical IMD components. Their high variation and plasticity may reflect adaptations to species-specific immune pressures, pathogen interactions. The cross activation of the immune signaling pathways, mainly mediated by Doral/Dif transcription factors illustrates the elder evolution of this pathway and their capacity to recruit IMD a probably evolutive adaptation to broaden humoral immune responses in insects, including hemipterans.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by a grant from the Fundación para la Investigación y Educación en Salud Pública A.C. (FIESP) to the project 'Análisis de procesos y moléculas que participan en la Respuesta Inmune humoral contra bacterias en Triatoma pallidipennis', SIID 2632 and CI 2031.

References

2. Lemaitre B, Hoffmann J. The host defense of Drosophila melanogaster. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:697–743.

3. Pradeu T, Thomma BPHJ, Girardin SE, Lemaitre B. The conceptual foundations of innate immunity: Taking stock 30 years later. Immunity. 2024 Apr 9;57(4):613–31.

4. Hoffmann JA, Reichhart JM. Drosophila innate immunity: an evolutionary perspective. Nat Immunol. 2002 Feb;3(2):121–6.

5. Tzou P, De Gregorio E, Lemaitre B. How Drosophila combats microbial infection: a model to study innate immunity and host-pathogen interactions. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2002 Feb;5(1):102–10.

6. Binggeli O, Neyen C, Poidevin M, Lemaitre B. Prophenoloxidase activation is required for survival to microbial infections in Drosophila. PLoS Pathog. 2014 May 1;10(5):e1004067.

7. Ao J, Ling E, Yu XQ. Drosophila C-type lectins enhance cellular encapsulation. Mol Immunol. 2007 Apr;44(10):2541–8.

8. Engström Y. Induction and regulation of antimicrobial peptides in Drosophila. Dev Comp Immunol. 1999 Jun-Jul;23(4-5):345–58.

9. Zou Z, Evans JD, Lu Z, Zhao P, Williams M, Sumathipala N, et al. Comparative genomic analysis of the Tribolium immune system. Genome Biol. 2007;8(8):R177.

10. Evans JD, Aronstein K, Chen YP, Hetru C, Imler JL, Jiang H, et al. Immune pathways and defence mechanisms in honey bees Apis mellifera. Insect Mol Biol. 2006 Oct;15(5):645–56.

11. Waterhouse RM, Kriventseva EV, Meister S, Xi Z, Alvarez KS, Bartholomay LC, et al. Evolutionary dynamics of immune-related genes and pathways in disease-vector mosquitoes. Science. 2007 Jun 22;316(5832):1738–43.

12. Buchon N, Silverman N, Cherry S. Immunity in Drosophila melanogaster--from microbial recognition to whole-organism physiology. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014 Dec;14(12):796–810.

13. Bulet P, Hetru C, Dimarcq JL, Hoffmann D. Antimicrobial peptides in insects; structure and function. Dev Comp Immunol. 1999 Jun-Jul;23(4-5):329–44.

14. Myllymäki H, Valanne S, Rämet M. The Drosophila imd signaling pathway. J Immunol. 2014 Apr 15;192(8):3455–62.

15. Agaisse H, Perrimon N. The roles of JAK/STAT signaling in Drosophila immune responses. Immunol Rev. 2004 Apr;198:72–82.

16. Levashina EA, Ohresser S, Lemaitre B, Imler JL. Two distinct pathways can control expression of the gene encoding the Drosophila antimicrobial peptide metchnikowin. J Mol Biol. 1998 May 8;278(3):515–27.

17. Gottar M, Gobert V, Matskevich AA, Reichhart JM, Wang C, Butt TM, et al. Dual detection of fungal infections in Drosophila via recognition of glucans and sensing of virulence factors. Cell. 2006 Dec 29;127(7):1425–37.

18. Rämet M, Manfruelli P, Pearson A, Mathey-Prevot B, Ezekowitz RA. Functional genomic analysis of phagocytosis and identification of a Drosophila receptor for E. coli. Nature. 2002 Apr 11;416(6881):644–8.

19. Naitza S, Rossé C, Kappler C, Georgel P, Belvin M, Gubb D, et al. The Drosophila immune defense against gram-negative infection requires the death protein dFADD. Immunity. 2002 Nov;17(5):575–81.

20. Kaneko T, Yano T, Aggarwal K, Lim JH, Ueda K, Oshima Y, et al. PGRP-LC and PGRP-LE have essential yet distinct functions in the Drosophila immune response to monomeric DAP-type peptidoglycan. Nat Immunol. 2006 Jul;7(7):715–23.

21. Hu S, Yang X. dFADD, a novel death domain-containing adapter protein for the Drosophila caspase DREDD. J Biol Chem. 2000 Oct 6;275(40):30761–4.

22. Aggarwal BB. Signalling pathways of the TNF superfamily: a double-edged sword. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003 Sep;3(9):745–56.

23. Silverman N, Zhou R, Stöven S, Pandey N, Hultmark D, Maniatis T. A Drosophila IkappaB kinase complex required for Relish cleavage and antibacterial immunity. Genes Dev. 2000 Oct 1;14(19):2461–71.

24. Tanji T, Yun EY, Ip YT. Heterodimers of NF-kappaB transcription factors DIF and Relish regulate antimicrobial peptide genes in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010 Aug 17;107(33):14715–20.

25. Shi YR, Jin M, Ma FT, Huang Y, Huang X, Feng JL, et al. Involvement of Relish gene from Macrobrachium rosenbergii in the expression of anti-microbial peptides. Dev Comp Immunol. 2015 Oct;52(2):236–44.

26. Michel T, Reichhart JM, Hoffmann JA, Royet J. Drosophila Toll is activated by Gram-positive bacteria through a circulating peptidoglycan recognition protein. Nature. 2001 Dec 13;414(6865):756–9.

27. Buchon N, Poidevin M, Kwon HM, Guillou A, Sottas V, Lee BL, et al. A single modular serine protease integrates signals from pattern-recognition receptors upstream of the Drosophila Toll pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009 Jul 28;106(30):12442–7.

28. Imler JL, Hoffmann JA. Signaling mechanisms in the antimicrobial host defense of Drosophila. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2000 Feb;3(1):16–22.

29. Christophides GK, Zdobnov E, Barillas-Mury C, Birney E, Blandin S, Blass C, et al. Immunity-related genes and gene families in Anopheles gambiae. Science. 2002 Oct 4;298(5591):159–65.

30. Simão FA, Waterhouse RM, Ioannidis P, Kriventseva EV, Zdobnov EM. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics. 2015 Oct 1;31(19):3210–2.

31. Giraldo-Calderón GI, Emrich SJ, MacCallum RM, Maslen G, Dialynas E, Topalis P, et al. VectorBase: an updated bioinformatics resource for invertebrate vectors and other organisms related with human diseases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015 Jan;43(Database issue):D707–13.

32. Nishide Y, Kageyama D, Yokoi K, Jouraku A, Tanaka H, Futahashi R, et al. Functional crosstalk across IMD and Toll pathways: insight into the evolution of incomplete immune cascades. Proc Biol Sci. 2019 Feb 27;286(1897):20182207.

33. Salcedo-Porras N, Guarneri A, Oliveira PL, Lowenberger C. Rhodnius prolixus: Identification of missing components of the IMD immune signaling pathway and functional characterization of its role in eliminating bacteria. PLoS One. 2019 Apr 3;14(4):e0214794.

34. Zhang CR, Zhang S, Xia J, Li FF, Xia WQ, Liu SS, et al. The immune strategy and stress response of the Mediterranean species of the Bemisia tabaci complex to an orally delivered bacterial pathogen. PLoS One. 2014 Apr 10;9(4):e94477.

35. Arp AP, Hunter WB, Pelz-Stelinski KS. Annotation of the Asian Citrus Psyllid Genome Reveals a Reduced Innate Immune System. Front Physiol. 2016 Nov 29;7:570.

36. Ma L, Liu S, Lu P, Yan X, Hao C, Wang H, et al. The IMD pathway in Hemipteran: A comparative analysis and discussion. Dev Comp Immunol. 2022 Nov;136:104513.

37. Bao YY, Qu LY, Zhao D, Chen LB, Jin HY, Xu LM, et al. The genome- and transcriptome-wide analysis of innate immunity in the brown planthopper, Nilaparvata lugens. BMC Genomics. 2013 Mar 9;14:160.

38. Shao ES, Lin GF, Liu S, Ma XL, Chen MF, Lin L, et al. Identification of transcripts involved in digestion, detoxification and immune response from transcriptome of Empoasca vitis (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae) nymphs. Genomics. 2017 Jan;109(1):58–66.

39. Mesquita RD, Vionette-Amaral RJ, Lowenberger C, Rivera-Pomar R, Monteiro FA, Minx P, et al. Genome of Rhodnius prolixus, an insect vector of Chagas disease, reveals unique adaptations to hematophagy and parasite infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015 Dec 1;112(48):14936–41.

40. Salcedo-Porras N, Oliveira PL, Guarneri AA, Lowenberger C. A fat body transcriptome analysis of the immune responses of Rhodnius prolixus to artificial infections with bacteria. Parasit Vectors. 2022 Jul 29;15(1):269.

41. Nishide Y, Kageyama D, Yoshida Y, Moriyama M, Fukatsu T. Functionality of highly diverged Imd like genes identified in stinkbugs and bedbugs. Sci Rep. 2025 Jun 4;15(1):19520.

42. Zumaya-Estrada FA, Martínez-Barnetche J, Lavore A, Rivera-Pomar R, Rodríguez MH. Comparative genomics analysis of triatomines reveals common first line and inducible immunity-related genes and the absence of Imd canonical components among hemimetabolous arthropods. Parasit Vectors. 2018 Jan 22;11(1):48.

43. Whitten MM, Mello CB, Gomes SA, Nigam Y, Azambuja P, Garcia ES, et al. Role of superoxide and reactive nitrogen intermediates in Rhodnius prolixus (Reduviidae)/Trypanosoma rangeli interactions. Exp Parasitol. 2001 May;98(1):44–57.

44. Whitten M, Sun F, Tew I, Schaub G, Soukou C, Nappi A, et al. Differential modulation of Rhodnius prolixus nitric oxide activities following challenge with Trypanosoma rangeli, T. cruzi and bacterial cell wall components. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2007 May;37(5):440–52.

45. Foley E, O'Farrell PH. Nitric oxide contributes to induction of innate immune responses to gram-negative bacteria in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 2003 Jan 1;17(1):115–25.

46. Carton Y, Frey F, Nappi AJ. Parasite-induced changes in nitric oxide levels in Drosophila paramelanica. J Parasitol. 2009 Oct;95(5):1134–41.

47. Gerardo NM, Altincicek B, Anselme C, Atamian H, Barribeau SM, de Vos M, et al. Immunity and other defenses in pea aphids, Acyrthosiphon pisum. Genome Biol. 2010;11(2):R21.

48. Benoit JB, Adelman ZN, Reinhardt K, Dolan A, Poelchau M, Jennings EC, et al. Unique features of a global human ectoparasite identified through sequencing of the bed bug genome. Nat Commun. 2016 Feb 2;7:10165.

49. Lhocine N, Ribeiro PS, Buchon N, Wepf A, Wilson R, Tenev T, et al. PIMS modulates immune tolerance by negatively regulating Drosophila innate immune signaling. Cell Host Microbe. 2008 Aug 14;4(2):147–58.

50. Shelby KS. Functional Immunomics of the Squash Bug, Anasa tristis (De Geer) (Heteroptera: Coreidae). Insects. 2013 Nov 26;4(4):712–30.

51. Chen W, Hasegawa DK, Kaur N, Kliot A, Pinheiro PV, Luan J, et al. The draft genome of whitefly Bemisia tabaci MEAM1, a global crop pest, provides novel insights into virus transmission, host adaptation, and insecticide resistance. BMC Biol. 2016 Dec 14;14(1):110.

52. Kim JH, Min JS, Kang JS, Kwon DH, Yoon KS, Strycharz J, et al. Comparison of the humoral and cellular immune responses between body and head lice following bacterial challenge. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2011 May;41(5):332–9.

53. Smith AA, Pal U. Immunity-related genes in Ixodes scapularis--perspectives from genome information. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2014 Aug 22;4:116.

54. Kounatidis I, Ligoxygakis P. Drosophila as a model system to unravel the layers of innate immunity to infection. Open Biol. 2012 May;2(5):120075.

55. Valanne S, Myllymäki H, Kallio J, Schmid MR, Kleino A, Murumägi A, et al. Genome-wide RNA interference in Drosophila cells identifies G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 as a conserved regulator of NF-kappaB signaling. J Immunol. 2010 Jun 1;184(11):6188–98.

56. Yokoi K, Koyama H, Minakuchi C, Tanaka T, Miura K. Antimicrobial peptide gene induction, involvement of Toll and IMD pathways and defense against bacteria in the red flour beetle, Tribolium castaneum. Results Immunol. 2012 Mar 30;2:72–82.

57. Alvarado-Delgado A, Juárez-Palma L, Martínez-Barneche J, Rodriguez MH. The IMD and Toll canonical immune pathways of Triatoma pallidipennis are preferentially activated by Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria, respectively, but cross-activation also occurs. Parasit Vectors. 2022 Jul 12;15(1):256.

58. Juárez-Palma L, Alvarado Delgado A, Rodriguez MH. Preferential Induction of Anonical IMD and Toll Innate Immune Receptors by Bacterial Challenges in Triatoma pallidipennis Primed with Gram-Negative and Gram-Positive Bacteria, Respectively. London J. Medical Health Research. 2024 Feb 23;24(2):1.

59. Kurtz J. Specific memory within innate immune systems. Trends Immunol. 2005 Apr;26(4):186–92.

60. Contreras‐Garduño J, Lanz‐Mendoza HU, Franco B, Nava A, Pedraza‐Reyes MA, Canales‐Lazcano JO. Insect immune priming: ecology and experimental evidences. Ecol Entomol. 2016 Aug;41(4):351–66.

61. Horng T, Medzhitov R. Drosophila MyD88 is an adapter in the Toll signaling pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001 Oct 23;98(22):12654–8.

62. Han ZS, Ip YT. Interaction and specificity of Rel-related proteins in regulating Drosophila immunity gene expression. J Biol Chem. 1999 Jul 23;274(30):21355–61.