Abstract

With the global economic development, the use of plastic has increased significantly. Currently, over 8.3 Gt of plastic is produced annually and approximately 6.3 Gt is discarded. Furthermore, 99% of the plastic is obtained from petroleum. When the plastic is obtained from petroleum, the carbon moves in one direction from the underground into the atmosphere in the form of CO2 gas, which is unsustainable, thereby requiring the development of a carbon recycling process that is independent of oil. The plastic waste is inadequately treated, which results in a substantial amount of plastics being released into the environment, thereby creating micro- and nano-plastic problems. Although bioplastics, such as polylactic acids, polyhydroxyalkanoates, and polybutylene succinate, are being actively researched and developed as alternatives to petroleum-based plastics, they have not been able to replace petroplastics yet due to their complex production processes and high cost. Therefore, we develop an alternative method for manufacturing bioplastics, wherein cells of unicellular green algae are used as the raw material; the plastics obtained are known as cell-plastics. The direct use of green algal cells for plastic production has several advantages. Through photosynthesis, green algae use CO2 as the carbon source to construct new cells; therefore, depending on the rate of CO2 assimilation, the growth activity of the grown cell is greater than that of the ordinary terrestrial plants. Algal cells have shown potential for application in robust cell-plastics owing to their rigid cell wall structure. Although cell-plastics are currently under trial in laboratory, we believe that they will be suitable for industrial-scale production.

Keywords

Sustainable society; Carbon recycle; Bioplastics; Unicellular green alga; Cell-plastics

Plastic Production

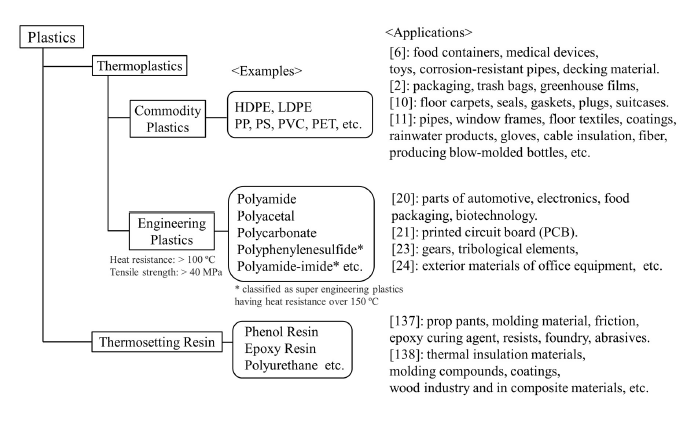

Plastic is a composite material made from organic polymers and can be freely molded into a film, fiber, or plate by heat or pressure processing. In 1839, Goodyear proposed the vulcanization of natural rubbers, while E. Simon discovered polystyrene [1]. From the viewpoint of mass production and cost-effectiveness, low-density polyethylene (LDPE) [2-4], high-density polyethylene (HDPE) [4-6], polypropylene (PP) [7-10], polyvinyl chloride (PVC) [11-13], polystyrene (PS) [14-16], and polyethylene terephthalate (PET) [17-19] have been recognized as general plastic materials. In addition, polymers that show heat-resistant temperature over 100°C and high tensile strength over 40 MPa have been categorized as engineering plastics, such as polyamide [20,21], polyacetal [22,23], and polycarbonate [24,25]. Overall, the use of resins that are synthesized by chemical methods have increased considerably since 20th century. In the 1940s, manufacturing industries developed owing to the improvement in the basic properties of polymers such as mechanical strength, flexibility, plasticity, heator chemical-registration. However, owing to the recent improvement in the quality of life, the mechanical strength of plastics has become crucial because plastics can replace metal or ceramic materials owing to their low cost. Plastics are used in several fields, including (1) the daily necessities such as bottles, packing supplies, grocery bags, clothes,furniture; (2) electronic devices, automobiles, and home appliances; and (3) aerospace materials (Figure 1). Plastic materials have become an indispensable part of the modern society, with 99% of the plastic materials being produced from petroleum, which is a non-recycled carbon resource [26]. In 2015, the cumulative plastic production worldwide was reported to exceed 8.3 Gt [27], which suggests that the amount of oil used was approximately the same as that of the plastics produced.

Figure 1. Classification of plastics and their applications.

Plastic Disposal

In recent years, the total amount of global plastic waste reached 6.3 Gt/year, which occupies an approximate volume of 5.9 km3 [27]. The increasing global population requires further production of plastics, thereby resulting in a significant increase in the amount of plastic waste. The amount of plastic waste is expected to reach up to 12 Gt by 2050 [27]. The disposal process of the plastic wastes is such that only 21% of the total plastic can be recycled or incinerated, and therefore, the rest is left untreated the environment [27]. When plastic waste is incinerated, CO2 gas, which contributes to the greenhouse effect, toxic chemical-ashes, and slag, is released into the environment, thereby damaging the environment due to the greenhouse effect and the effects of other pollutants [28]. Plastic incineration processes emit 400 Mt of CO2/ year into the atmosphere, which seriously impacts the environment. In contrast, since most untreated plastic waste is controlled as normal waste by the authorities, systematic control of plastic waste for storage and degradation is difficult, even with progressive controls in urban areas. Due to waste-disposal mismanagement, significant amounts of plastic waste have been released and accumulated in the environment. Furthermore, 4% of the waste plastic is transported into rivers by rainwater, which eventually reaches the sea. Therefore, there is a considerable contamination load stress on the biological ocean-environment [29-32]. In the ocean, large amounts of degraded plastic patches have accumulated, which have resulted in death of the ocean organisms and food insecurity [33]. The plastic waste remains in the environment for a long time owing to their high durability. For instance, several research have reported that the plastic materials (e.g., bottles, containers, and trays) made of PET via petrochemistry have maintained their form in the environment for 90 years [34,35]. Another research has reported that the effects of these plastic wastes on the environment will worsen increasingly in the future [36]. Therefore, plastic contamination for a long duration affects biogeocenosis and causes serious problems, such as environmental pollution and destruction of ecosystem [37].

Risk of Micro Plastics

Along with the accumulation of plastic wastes on land, the environmental pollution caused by microplastics in the ocean is also concerning. Microplastics are defined as plastic pieces with diameter of 5 mm or less [38]. Previous reports have shown that approximately 13% of plastic refuse is classified as microplastics [38]. Among them, the plastic pieces with diameters of 1.01–4.75 mm have an adverse effect on the marine ecosystem, especially the food chain. Although the area occupied by microplastics in the Pacific Ocean is approximately 1% (1.6 million km2/165 million km2), the problem of environmental pollution by microplastics is of global significance because the affected area is spreading rapidly [39]. According to another study, the microplastics spread in the oceans have a density of 1 × 106 pieces/km2 [38]. Microplastics have been found in temperate oceans and near the North and South Pole [38]. Furthermore, the microplastics have been found on the sea floor and in sediment [40-42].

Recently, the environmental load of general plastics, such as PE, PP, PS, and PET [43-45], was investigated from the viewpoint of environmental science, microbiology, genetics, and toxicology [46-49]. In addition, it was revealed that organisms in the oceans, which ingested microplastics, experienced induced disruption of biological processes, gastrointestinal irritation, changes in the microbiome, lipid metabolism, and oxidative stress [50-52]. Moreover, besides damage and inflammation to living things themselves, they contain several kinds of environmental pollutants, such as endogenous plastic additives, metals, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, chlorinated hydrocarbons, and pathogenic microorganisms. From the viewpoint of human food, microplastics have been found in fish, salt, beer, sugar, and bottled water [49]. Consumption of food that contain microplastics increases the risk of cancer and other diseases [53]. In addition, the mobility of harmful substances in the human body is accelerated by inhalation of microplastics, which increases the possibility of serious illness due to biological concentration.

Requests for Bioplastics as Sustainable Sources

Owing to the serious global problems related to the plastic waste, China, which is one of the countries that accepted plastic wastes, declared that it will no longer be receiving waste from other countries for recycling after December 31, 2017 [54]. Global actions, such as the Chinese declaration, require the development of plastic materials using nonpetroleum resources. Therefore, bioplastics have been chosen as alternatives to oil-based plastics. In the near future, approximately 11 Mt of the oil-based plastics are expected to be replaced by the bio-based variant [54].

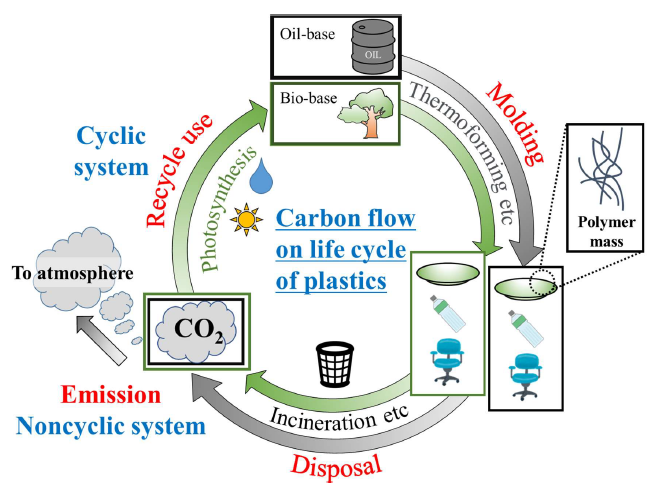

With regard to the expansion of a circular bioeconomy, research and development of recyclable plastics that can degrade into CO2 without any byproducts have attracted international attention (Figure 2). From the viewpoint of circular bioeconomy, the balance between resources and plastic waste can be maintained by recycling plastic through appropriate treatment methods. Although there has recently been some improvement in the recycling of plastic waste, the success has been minor despite an increase in global intentions for plastic recycling. Note that the ratio of plastic recycling globally is approximately 20% [27], whereas in Europe, it is only 6% [55]. Therefore, research and development based on the direct conversion of plastic waste to useful plastic materials and carbon source conversion via CO2 in biogeocenosis has attracted significant attention worldwide. For instance, Europe, which has a strong desire for plastic reduction, realizes 25.8 Mt of plastic waste per year, with 59% of the plastic waste derived from packaging materials [28]. Therefore, the replacement of packaging plastics with a circular resource will resolve a major part of their environmental problems. Following the damage to the environment that has resulted from the production and discarding of plastics, extensive environmental campaigns have been conducted for minimizing plastic waste. Therefore, over the last 20 years, academic communities have made progress in the development of bioplastics as circular resources [56,57]. Although the main discussions in the research have been whether plastics maintain their physical and chemical properties for commercial use and if biodegradability violates the criterion for industrial use [57,58]. Thus far, no developed bioplastics have met all the criteria [58,59]. Therefore, plastic production (including bioplastics) and the associated environmental effects, along with acute effects on developments and dwellings, should be reconsidered to curb plastic pollution and realize sustainability [60-62].

Figure 2. Schematic model of carbon flow on life cycle of plastics.

Definition of Bioplastics

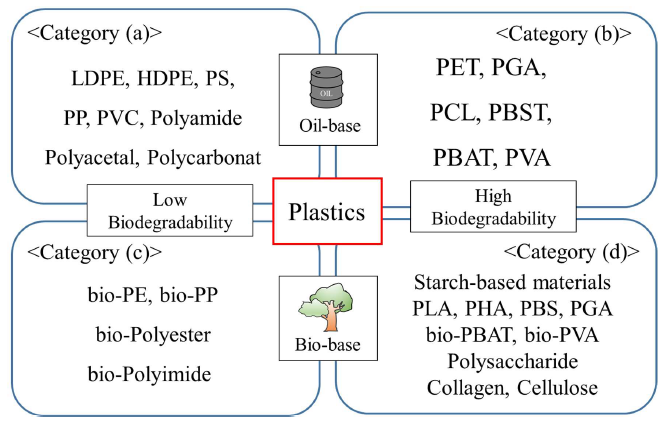

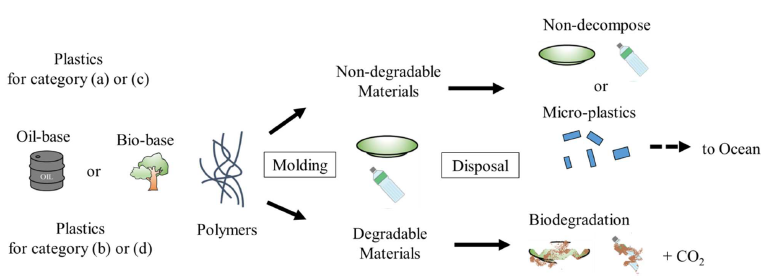

Based on the raw materials and biodegradability, plastics are classified as follows: (a) Oil-based with low biodegradability; (b) oil-based with high biodegradability; (c) biomass based with low biodegradability; and (d) biomass based with high biodegradability (Figure 3). Bioplastics are defined as either highly biodegradable plastics, i.e., (b) and (d), or plastics of categories (b), (c), and (d). In this study, we treat the latter definition as bioplastics. Oil-based plastics with high biodegradability include PET [27], poly(glycolic acid) (PGA), poly(caprolactone) (PCL), poly(butylene succinate-coterephthalate) (PBST), poly(butylene adipateco- terephthalate) (PBAT), and poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA). Note that because the carbon source in oil-based plastics with high biodegradability is petroleum, the carbon moves in one direction from the underground into the atmosphere in the form of CO2 gas. Biomass based plastics with low biodegradability include well-known plastics such as bio- PE, bio-PP, bio-polyester, and bio-polyimide. Biomass based plastics with high biodegradability include the following polymer materials: Starch-based materials [63-65], polylactic acid (PLA) [66,67], polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) [66,68,69], polybutylene succinate (PBS) [70], bio-polybutylene adipate terephthalate (bio-PBAT) [71], polyglycolate (PGA), polysaccharide, collagen, bio- PVA [72-75], cellulose, pectin, and chitin. Among these bioplastics, production of PLA and starch-based materials accounts for approximately 10.3% and 18.2%, respectively, of the total amount of the bioplastics in the environment [76] (Figure 4). In addition, because PHAs, PGA, and mixtures of biodegradable polymers are plastics, which are decomposed in a short duration by microbes under suitable conditions, they have already been adopted for practical use [77]. Note that several bioplastics produce fragments with micro- to nano-size owing to biodegradation under unsuitable conditions [78-80], which would affect the environment and human health [81]. In addition to biodegradation, several synthetic polymers show oxidative degradability. Note that plastics with oxidative degradability do not decompose less than the size of microplastics. However, the effect of oxidative degradable plastics on the environment is unclear, unlike that of biodegradable plastics.

Figure 3. Categorized plastics based on raw materials and biodegrability.

Figure 4. Flow model from production to disposal of each categolized plastic.

To decrease the global environmental pollution due to oilbased plastics with low biodegradability, there have been attempts to produce bioplastics from renewable resources as sustainable materials [38,82]. Bioplastic materials have been produced as packaging and catering products, parts of electronic devices and automobiles, agricultural and gardening supplies, toys, and fibers [56,76]. In addition, they have been used as coating materials for biodegradable films, package supplies, and non-combustible materials as an alternative to oil-based plastics [81]. Bioplastics are widely used in the field of agriculture. For example, they are used as protecting films for seeds. Changing the protecting film from oil-based plastics to bioplastics is advantageous for producing smaller amounts of waste [83-85], with a shorter degradation time and constant degradation rate than those of conventional oil-based films. Moreover, in the case of mixtures of bioplastics and B. subtilis spores (a plant growth promoting bacteria), it was revealed that the rate of biodegradation increased [85]. Overall, research has progressed in this area.

However, in 2017–2018, it was reported that the production of bioplastics was approximately 1% of the total amount of plastics in the environment [76]. Although their producibility gradually increases, it is presumed that the amount of production of the bioplastics will increase from 2.11 million tons in 2018 to only 2.62 million tons in 2023. This is because the production cost of biodegradable plastics is significantly higher than that of the oil-based varieties, although famers have recognized the importance of alternative plastics for a sustainable society. Further development of biodegradable plastics is required to assess their future social impact.

Anticipation for Designs of Bioplastics as Future Resources

Bioplastics are relatively new materials in various fields, and their use is increasing in the global market.

As described above, bioplastics meet the criteria for biobased and/or biodegradability. Considering the circular economy based on carbon sources, future preference will be given to bio-based plastics that directly use CO2 gas available in atmosphere as a carbon source. Research and development have shown some progress in the expansion of bio economics owing to the design of the bioplastics that can degrade into CO2 over a duration of a few months or years. These were developed based on the carbon circular process. For instance, some bioplastic bottles designed for water storage could retain their form for several years indoors, whereas bottles of the same materials would degrade in relatively shorter times when in the outside environment. Conversely, the use of bioplastics as rigid resources, including for traffic infrastructure such as road surfaces and building structures, will be preferred because CO2 can be captured in the resources for a long time. These ideas should involve the production of bioplastics using atmospheric CO2 as a carbon source. Photosynthetic organisms, including higher plants and microalgae, assimilate CO2 into organic chemicals as feedstocks for light-energy bioplastics. For example, PHB produced by cyanobacteria could be used as a feedstock [69]. The photosynthetic organisms can grow and produce feedstocks using inorganic substances, including nitrogen and phosphate, suggesting that the produced feedstock can be used as circular resource for carbon and other inorganic materials. Therefore, bioplastics, which are different from oil-based plastics, can be used as organic wastes containing rich nutrients for fertilizers and composts [86-89]. For their use as fertilizers and composts in the environment, degradability, safety, and removal of pollutants and organic waste should be certified [90]. In response to these requirements, several research have reported the results of degradation reactions under aerobic/anaerobic conditions in the environment [86]. Furthermore, discarded PHA can be degraded by microbials and supplied as carbon and energy sources to other organisms [91]. The supplier of feedstock for bioplastics should also consider the cultivating place of photosynthetic organisms to avoid competition for food. Although most bioplastics are currently produced using food-based feedstock such as carbohydrate, achieving SDGs is difficult because of the competition for cropland, water resources, and food supply [92]. Therefore, the system using microalgae, including cyanobacteria and green algae, has the advantages of producing and supplying resources for next-generation bioplastics because these photosynthetic organisms can be cultivated in fresh water and/or seawater and not terrestrial cropland [93,94]. If the production and supply of resources using microalgae becomes a successful strategy, the system will contribute to SDGs.

The competitors in bioplastics market achieve supply by reducing production costs and increasing quality. Therefore, the process of extracting and fractionating components of bioplastics from biomass has already been practiced for a long time [95]. For instance, the mechanical cracking method for cells and processes of using supercritical water have been extensively studied. Therefore, efficient extraction and fractionation of carbohydrates, lipids, proteins, nucleolus, and cell walls have been improved. These approaches have exhibited the possibility for realization of bioplastics without the high costs of fractionation. Furthermore, progress in the CRISPR technology used on microalgae can lead to the optimization of light-harvesting efficiency and installation of novel metabolic pathways in the cells [96,97]. Genetic engineering for improving specific metabolic pathways allows the possibility of increasing the productivity of valueadded materials using microalgae. Although the GMOs require particular attention to deter them from escaping externally, the use of GMOs can result in an efficient process and reduction of production costs. Especially, the production of value-added substances using microalgal GMOs can resolve the problem of high cost. In addition, the parallel production of resources for bioplastics from the same biomass can result in reduced cost.

For biodegradable plastics, it is necessary to set suitable conditions for biodegradation. Under unsuitable conditions, small pieces, such as micro- or nano-plastics, can be produced and get accumulated in the environment before the complete biodegradation of bioplastic. Microplastics that originated from bioplastics affect the ecosystems at coastal waters and on the deep seafloor [29,98], similar to oil-based plastics [29,98-101]. For example, when PLA is accumulated on the deep seafloor, the Ostrea edulis, known as the flat oyster and Arenicola marina L [98], become stressed and their breathing rates increase. The exposure of microplastics, namely PHB and polymethylmethacrylate, which is a petroleumbased plastic, to Gammarus fossarum resulted in a reduction in its assimilation [99]. Moreover, in the case of Anabena sp. PCC7120 and C. reinhardtii, significant reduction in their cell proliferation and modifications in relevant physiological parameters were found. Conversely, for the crustacean Daphnia magna, the induction of immobilization and significant increase in intracellular reactive oxygen species levels were investigated [100]. Serious membrane damage in these three organisms was reported [100]. Other reports revealed that mortality increased, whereas the feeding rate and fertility decreased in the case of D. magna exposed by microplastics of PS [102]. In comparison with the oil-based microplastics, biodegradable plastics could be a vector that injects pollutants into the body [101,103-107], thereby suggesting that plastics dispersed in the environment have a negative impact on the ecosystem, including bioplastics. There are several unclear points in the biodegradation process of the microplastics of bioplastics [28,108]. Given the recent development in the field of bioplastics, there is a gap between the environmental impacts of microplastics and our findings.

Studies have been conducted on the overall process of degradation, such as end-of-life options [109], photolysis and thermal oxidative degradation [110-112], and biodegradation [111,113-115] to understand the degradations of the bioplastics that are designed to break down into small molecules, (e.g., monomers, dimers, and oligomers) in the environment. Recently, utilization of microbial strains involved in the degradation process has been evaluated because microorganisms decompose the organic substrate of the bioplastics [115]. To understand the degradation process, biodegradation process under dry/wet or aerobic/anaerobic conditions have been tested. Real-life tests directly evaluate the decomposition of bioplastics in the environment [116,117]. Biodegradation of bioplastics is evaluated based on (ultimate) biodegradability, disintegration, and compost quality [28,111,117]. Biodegradability is the ability of bioplastics to be broken down into small molecules by both biological and abiotic effects during hydrolysis process. Disintegration means physically crushing substances to small pieces [118]. The compost quality is evaluated by measuring the weight of microplastics with sizes more than 2 mm, which is found by sieving of compost [119-121]. Note that to the best of our knowledge, there is no protocol for monitoring plastics with size less than 2 mm. The information on the effects of test substances is provided through environmental toxicity tests conducted in the cultivated land [113]. Moreover, degradation in several different types of bioplastics was evaluated for the contribution of the physical and chemical properties of bioplastics to biodegradation [92,105,115,122], in addition to the conditions of the production process. Note that physical and chemical properties, which are considered for biodegradation in the environment, are hydrophilicity, surface area, molecular weight, chemical structures, and higher order structures [122]. During the biodegradation process, plastic fragmentation proceeds by physical process, such as polishing power, heating/cooling, freeze/ thaw, and wet/dry, and chemical process, such as oxidation and hydrolysis [123,124]. In the case of biodegradation in the environment, several microbial enzymes such as depolymerase, lipase, cutinase, hydrolase, protease, and lignin modifying enzyme cleave polymers to oligomers, dimers, and monomers [125]. Fragments pass through the cell wall of microorganisms; therefore, they are eventually decomposed into carbon dioxide when they are used as a substrate for microorganisms [115]. Comprehensive analysis shows that monomers belonging to the metabolic processes of cells produce energy that cause decomposition into water, carbon dioxide, biomass, and other basic products through various metabolic and enzymatic mechanisms [125]. Therefore, when the bioplastic is made of raw, recyclable materials that are universally present in environment, they would be treated as eco-friendly materials because they would be easily decomposed in the environment and be ingested by organisms.

Cell-plastics as Neo-plastics

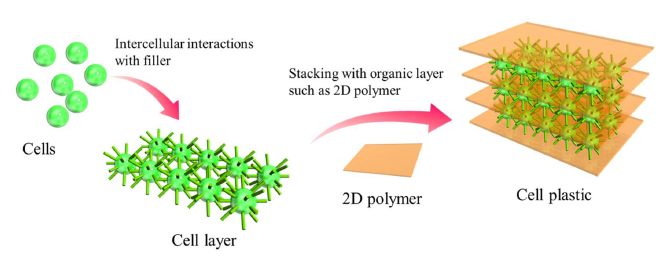

As described above, the use of bioplastics is not wide spread yet owing to their costs. Thus, the production of a new circular resource, which can be serve as an alternative to the oil-based plastics, is crucial. Recently, a novel bioplastic made of green algal cells was reported [126]. Chlamydomonas reinhardtii is a unicellular green alga that self-propagates using CO2 as a carbon source [127]. C. reinhardtii can be used as an industrial strain as follows owing to the good proliferative productivity (10–50 times higher assimilating activity of CO2 than that of popular terrestrial plants [128]), properties producing value-added materials such as lipids and carotenoids [129,130], and bio-safety with no reports about toxicity [131]. The cells are significantly rigid, and therefore, the breaking cells that extract intercellular materials require powerful breaking methods, such as beads beater [132]. Although the rigidness and robustness of C. reinhardtii cells are the bottlenecks of extracting the intercellular components, its tough physical properties make it a potential candidate to be used as an ingredient in plastics. In the case of using unicellular C. reinhardtii as a plastic resource, cells can be freely placed on empty spaces; however, cells require a filler to connect to each of the cells. In this study, glycerol and bovine serum albumin were used as filler, which connected the cells to each other, thereby constructing a cell-layer. The cell-layer was expected to be used as a plastic resource because of the possibility to be freely molded using templates and was referred to as “cell-plastics” [126]. As the cell-layer is a fragile material because of the weak interactions between the cells, it is necessary to improve mechanical strength for actual use. Therefore, stacked structures of cell-plastics were constructed by alternatively stacking the cell-layer and flexible thin organic film such as a two-dimensional polymer, which has a sheet-like structure with a twodimensional periodicity [133-136]. A self-standing film of the cell-plastic was thus manufactured, which was not realized only with the cell-layer (Figure 5). The plastic was composed of green algal cells, without the extraction of intercellular components and was produced as a nextgeneration bioplastic, possibly responding to the SDGs for the first time. The considerable research accomplishment is to be followed by progressing up to the next stage, wherein the cells could be used as direct ingredients of plastics with reduced costs. In future, cell-plastics that are durable in actual use should be fabricated using biodegradable fillers that have a good affinity with the cells via chemical or supramolecular interactions; furthermore, a carbon-recycling system should be achieved.

Figure 5. Schematic model of fabrication of cell-plastics.

Bioplastics exhibit high potential as an alternate for oilbased plastics, although they can damage the environment and biogeocenosis, similar to oil-based plastics, if their production and plastic waste disposal are ignored. However, there is no doubt about the future breakthrough of bioplastics, and we believe that production and discard of bioplastics will be considered sufficiently in the future.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by Feasibility Study Program of the New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization (NEDO). We appreciated the support by Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

References

2. Basfar AA, Idriss Ali KM. Natural weathering test for films of various formulations of low density polyethylene (LDPE) and linear low density polyethylene (LLDPE). Polymer Degradation and Stability. 2006 Mar;91(3):437– 43.

3. Sabetzadeh M, Bagheri R, Masoomi M. Study on ternary low density polyethylene/linear low density polyethylene/ thermoplastic starch blend films. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2015 Mar 30;119:126–33.

4. Paxtona NC, Allenbya MC, Lewisb PM, Woodruffa MA. Biomedical applications of polyethylene. European Polymer Journal. 2019 Sep;118:412–28.

5. Kiszka A, Łomozik M. Vibration welding of high density polyethylene HDPE - Purpose, application, welding technology and quality of joints. Kovove Materialy. 2013 Jan;51(1):63–70.

6. Pastrnak A, Henriquez A, Saponara VL. Parametric study for tensile properties of molded high density polyethylene for applications in additive manufacturing and sustainable designs. Journal of Applied Polymer Science. 2020 Nov 10;137(42): 49283.

7. Galli P, Danesi S, Simonazzi T. Polypropylene based polymer blends: fields of application and new trends. Polymer Engineering and Science. 1984 Jun;24(8):544–54.

8. Bedia EL, Astrini N, Sudarisman A, Sumera F, Kashiro Y. Characterization of polypropylene and ethylene– propylene copolymer blends for industrial applications. Journal of Applied Polymer Science. 2000 Nov 7;78(6):1200–8.

9. Busico V, Cipullo R. Microstructure of polypropylene. Progress in Polymer Science. 2001 Apr;26(3):443–533.

10. Chukova NA, Ligidovb MK, Pakhomovc SI, Mikitaevb AK. Polypropylene polymer blends. Russian Journal of General Chemistry. 2017;87(9):2238–49.

11. Braun D. Poly(vinyl chloride) on the way from the 19th century to the 21st century. Journal of Polymer Science: Part A: Polymer Chemistry. 2004 Feb 1;42(3):578–86.

12. Moulay S. Chemical modification of poly(vinyl chloride)—Still on the run. Progress in Polymer Science. 2010 Mar;35(3):303–31.

13. Chiellini F, Ferri M, Morellia A, Dipaolac L, Latini G. Perspectives on alternatives to phthalate plasticized poly(vinyl chloride) in medical devices applications. Progress in Polymer Science. 2013 Jul;38(7):1067–88.

14. Puskas JE, Dahman Y, Margaritis A. Novel thymine-functionalized polystyrenes for applications in biotechnology. 2. Adsorption of model proteins. Biomacromolecules. 2004 Apr 21;5(4):1412–21.

15. Schellenberg J, Leder HJ. Syndiotactic polystyrene: process and applications. Advances in Polymer Technology. 2006 Oct 18;25(3):141–51.

16. Yap FL, Zhang Y. Assembly of polystyrene microspheres and its application in cell micropatterning.Biomaterials. 2007 May;28(14):2328–38.

17. MacDonald WA. New advances in poly(ethylene terephthalate) polymerization and degradation. Polymer International. 2002 Oct;51(10):923–30.

18. Bach C, Dauchy X, Chagnon MC, Etienne S. Chemical compounds and toxicological assessments of drinking water stored in polyethylene terephthalate (PET) bottles: A source of controversy reviewed. Water Research. 2012 Mar 1;46(3):571–83.

19. Çaykara T, Sande MG, Azoia N, Rodrigues LR, Silva CJ. Exploring the potential of polyethylene terephthalate in the design of antibacterial surfaces. Medical Microbiology and Immunology. 2020 Feb 9;209:363–72.

20. Chavarria F, Paul DR. Comparison of nanocomposites based on nylon 6 and nylon 66. Polymer. 2004 Nov;45(25):8501–15.

21. Zhang C. Progress in semicrystalline heat-resistant polyamides. e-Polymers. 2018 Aug 3;18(5):373–408.

22. Kawaguchi K, Masuda E, Tajima Y. Tensile behavior of glass-fiber-filled polyacetal: influence of the functional groups of polymer matrices. Journal of Applied Polymer Science. 2008 Jan 5;107(1):667–73.

23. Shibata K, Toyabe K, Araki R, Yamaguchi T, Kawabata M, Hokkirigawa K. Tribological behavior of polyacetal composite lubricated in sodium hypochlorite solution. Wear. 2019 Jun 15;428–429:272–278.

24. Wang YZ, Yi B, Wu B, Yang B, Liu Y. Thermal behaviors of flame-retardant polycarbonates containing diphenyl sulfonate and poly(sulfonyl phenylene phosphonate). Journal of Applied Polymer Science. 2003 Jul 25;89(4):882–9.

25. Levchil SV, Weil ED. Overview of recent developments in the flame retardancy of polycarbonates. Polymer International. 2005 Jul;54(7):981–98.

26. Ciel. Fossils, plastics, & petrochemical feedstocks. In Fueling Plastics 2017 (pp. 1–5). Center for International Environment Law, Washington DC.

27. Geyer R, Jambeck JR, Law KL Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Science Advances. 2017 Jul 5;3(7):e1700782.

28. Emadian SM, Onay TT, Demirel B. Biodegradation of bioplastics in natural environments. Waste Management. 2017 Oct 11;59:526–36.

29. Green DS, Boots B, Blockley DJ, Rocha C, Thompson R. Impacts of discarded plastic bags on marine assemblages and ecosystem functioning. Environmental Science and Technology. 2015 Mar 30;49(9):5380–9.

30. Jain R, Tiwari A. Biosynthesis of planet friendly bioplastics using renewable carbon source. Journal of Environmental Health Science and Engineering. 2015 Feb 15;13(11).

31. Mostafa NA, Farag AA, Abo-dief HM, Tayeb AM. Production of biodegradable plastic from agricultural wastes. Arabian Journal of Chemistry. 2018 May;11(4):546–53.

32. Pathak S, Sneha CLR, Mathew BB. Bioplastics: Its time line based scenario & challenges. Journal of Polymer and Biopolymer Physics Chemistry. 2014;2(4):84–90.

33. Varsha YM, Savitha R. Overview on polyhydroxyalkanoates: a promising biopol. Journal of Microbial & Biochemical Technology. 2011 Jan;3(5):99– 105.

34. Edge M, Hayes M, Mohammadian M, Allen NS, Jewitt TS, Brems K, et al. Aspects of poly (ethylene terephthalate) degradation for archival life and environmental degradation. Polymer Degradation and Stability. 1991;32(2):131–53.

35. Allen NS, Edge M, Mohammadian M, Jpnes K. Physicochemical aspects of the environmental degradation of poly (ethylene terephthalate). Polymer Degradation and Stability. 1994;43(2):229–37.

36. Albertsson AC, Barenstedt C, Karlsson S, Lindberg T. Degradation product pattern and morphology changes as means to differentiate abiotically and biotically aged degradable polyethylene. Polymer. 1995;36(16):3075–83.

37. Jambeck JR, Geyer R, Wilcox C, Siegler TR, Perryman M, Andrady A, et al. Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean. Science. 2015 Feb 13;347(6223):768–71.

38. Eriksen M, Lebreton LCM, Carson HS, Thiel M, Moore CJ, Borerro JC, et al. Plastic pollution in the world’s oceans: more than 5 trillion plastic pieces weighing over 250,000 tons afloat at sea. PLoS One. 2014 Dec 10;9.

39. Lebreton L, Slat B, Ferrari F, Sainte-Rose B, Aitken J, Marthouse R, et al. Evidence that the great pacific garbage patch is rapidly accumulating plastic. Scientific Reports. 2018 Mar 22;8:4666.

40. Horton AA, Svendsen C, Williams RJ, Spurgeon DJ, Lahive E. Large microplastic particles in sediments of tributaries of the River Thames, UK – Abundance,sources and methods for effective quantification. Marine Pollution Bulletin. 2017 Jan 15;114(1):218–26.

41. Horton AA, Walton A, Spurgeon DJ, Lahive E, Svendsen C. Microplastics in freshwater and terrestrial environments: Evaluating the current understanding to identify the knowledge gaps and future research priorities. Science of the Total Environment. 2017 May 15;586:127– 41.

42. Ng EL, Huerta Lwanga E, Eldridge SM, Johnston P, Hu HW, Geissen V, et al. An overview of microplastic and nanoplastic pollution in agroecosystems. Science of the Total Environment. 2018 Jun 15;627:1377–88.

43. Wang W, Gao H, Jin S, Li R, Na G. The ecotoxicological effects of microplastics on aquatic food web, from primary producer to human: a review. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety. 2019 May 30;173:110–7.

44. Prata JC, da Costa JP, Lopes I, Duarte AC, Rocha- Santos T. Effects of microplastics on microalgae populations: a critical review. Science of the Total Environment. 2019 May 15;665:400–5.

45. Botterell ZLR, Beaumont N, Dorrington T, Steinke M, Thompson RC, Lindeque PK. Bioavailability and effects of microplastics on marine zooplankton: a review. Environmental Pollution. 2019 Feb;245:98–110.

46. Koelmans AA, Mohamed-Nor NH, Hermsen E, Kooi M, Mintenig SM, de France J. Microplastics in freshwaters and drinking water: critical review and assessment of data quality. Water Research. 2019 May 15;155:410–22.

47. Alimba CG, Faggio C. Microplastics in the marine environment: current trends in environmental pollution and mechanisms of toxicological profile. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology. 2019 May;68:61–74.

48. Sun J, Dai X, Wang Q, van Loosdrecht MCM, Ni BJ. Microplastics in wastewater treatment plants: detection, occurrence and removal. Water Research. 2019 Apr 1;152:21–37.

49. Barboza LGA, Vethaak AD, Lavorante BRBO, Lundebye AK, Guilhermino L. Marine microplastic debris: an emerging issue for food security, food safety and human health. Marine Pollution Bulletin. 2018 Aug;133:336–48.

50. de Sá LC, Oliveira M, Ribeiro F, Rocha TL, Futter MN. Studies of the effects of microplastics on aquatic organisms: what do we know and where should we focus our efforts in the future Science of the Total Environment. 2018 Dec 15;645:1029–39.

51. Germanov ES, Marshall AD, Bejder L, Fossi MC, Loneragan NR. Microplastics: no small problem for filterfeeding megafauna. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 2018 Apr;33(4)227–32.

52. Galloway TS, Lewis CN. Marine microplastics spell big problems for future generations. PNAS. 2016 Mar 1;113(9):2331–3.

53. Wright SL, Kelly FJ. Plastic and human health: a micro issue Environmental Science & Technology. 2017 May 22;51(12):6634–47.

54. Brooks AL, Wang S, Jambeck JR. The Chinese import ban and its impact on global plastic waste trade. Science Advance. 2018 Jun 1;4(6):eaat0131.

55. Filho WL, Shiel C, Paço A, Mifsud M, Ávila LV, Brandli LL, et al. Sustainable Development Goals and sustainability teaching at universities: Falling behind or getting ahead of the pack Cleaner Production. 2019 Sep 20;232:285–94.

56. Peelman N, Ragaert P, de Meulenaer B, Adons D, Peeters R, Cardon L, et al. Application of bioplastics for food packaging. Trends in Food Science and Technology. 2013 Jun 21;32(2):128–41.

57. Adhikari D, Mukai M, Kubota K, Kai T, Kaneko N, Araki KS, et al. Degradation of bioplastics in soil and their degradation effects on environmental microorganisms. Journal of Agricultural Chemistry and Environment. 2016 Feb 29; 5(1):23–34.

58. Rhim JW, Park HM, Ha CS. Bio-nanocomposites for food packaging applications. Progress in Polymer Science. 2013 Oct-Nov;38(10–11):1629–52.

59. Bugnicourt E, Cinelli P, Lazzeri A, Alvarez V. Polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA):review of synthesis, characteristics, processing and potential applications inpackaging, Express Polymer Letters. 2014 Jun;8(11):791– 808.

60. Crabbé A, Jacobs R, Van Hoof V, Bergmans A, Van Acker K. Transition towards sustainable material innovation: Evidence and evaluation of the Flemish case. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2013 Oct 1;56:63–72.

61. Pracht F. Luminaire synthetic materials and the environment. Light Engineering. 2011 Jan;19(3):71–7.

62. Ribeiro I, Peças P, Silva A, Henriques E. Life cycle engineering methodology applied to material selection, a fender case study. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2008 Nov;16(17):1887–99.

63. Jantanasakulwong K, Leksawasdi N, Seesuriyachan P, Wongsuriyasak S, Techapun C, Ougizawa T. Reactive blending of thermoplastic starch, epoxidized natural rubber and chitosan. European Polymer Journal. 2016 Nov;84:292–9.

64. Montero B, Rico M, Rodríguez-Llamazares S, Barral L, Bouza R. Effect of nanocellulose as a filler on biodegradable thermoplastic starch films fromtuber, cereal and legume. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2017 Feb 10;157:1094–104.

65. Sagnelli D, Hebelstrup KH, Leroy E, Rolland-Sabaté A, Guilois S, Kirkensgaard JJK, et al. Plant-crafted starches for bioplastics production. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2016 Nov 5;152:398–408.

66. Garavand F, Rouhi M, Razavi SH, Cacciotti I, Mohammadi R. Improving the integrity of natural biopolymer films used in food packaging by crosslinking approach: a review. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2017 Nov;104(A):687–707

67. Hottle TA, Bilec MM, Landis AE. Sustainability assessments of bio-based polymers. Polymer Degradation and Stability. 2013 Sep;98(9):1898–907.

68. Arraiza MP, López JV, Fernando A. Environmental security and solid waste management. Aerobic degradation of bioplastic materials. Proceeding from the 1st International Workshop on environmental security, geological hazards and management, San Cristobal de La Laguna, Tenerife (Canary Islands), Spain. 10–12 Apr 2013.

69. Meixner K, Kovalcik A, Sykacek E, Gruber- Brunhumerabe M, Zeilinger W, Markl K. et al. Cyanobacteria biorefinery—production of poly (3-hydroxybutyrate) with Synechocystis salina and utilization of residual biomass. Journal of Biotechnology. 2018 Jan 10;265:46–53.

70. Luzi F, Fortunati E, Jiménez A, Puglia D, Pezzolla D, Gigliotti G, et al. Production and characterization of PLA PBS biodegradable blends reinforced with cellulose nanocrystals extracted from hemp fibres. Industrial Crops and Production. 2016 Dec 25;93:276–89.

71. Byun Y, Kim YT. Bioplastics for food packaging: chemistry and physics. In Innovations in Food Packaging 2nd edition 2014 (pp. 353–65). Elsevier; Amsterdam.

72. Cioica N, Co´na C, Nagy M, Fodorean G. Plastics made from renewable sources – potential and perspectives for the environment and agriculture of the third millennium. Bulletin of the University of Agricultural Sciences and Veterinary Medicine. 2008;65(2): 23–8.

73. Flieger M, Kantorova M, Prell A, Rezanka T, Votruba J. Biodegradable plastics from renewable sources. Folia Microbiologica. 2003 Jan;48(27):27–44.

74. Jamshidian M, Tehrany EA, Imran M, Jacquot M. Poly-lactic acid:production, applications, nanocomposites, and release studies. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety. 2010 Aug 26;9:552–71.

75. Ojumu TV, Yu J, Solomon BO. Production of polyhydroxyalkanoates, abacterial biodegradable polymer. African Journal of Biotechnology. 2004 Jun 29;3(1):18– 24.

76. European Bioplastics. Bioplastics market data 2018. European Bioplastics, Berlin, Germany (2018).

77. Lambert S, Wagner M. Formation of microscopic particles during the degradation of different polymers. Chemosphere. 2016 Oct;161:510–517.

78. Kubowicz S, Booth AM. Biodegradability of plastics: challenges and misconceptions. Environmental Science & Technology. 2017 Oct 12;51(21):12058–60.

79. Haider TP, Völker C, Kramm J, Landfester K, Wurm FR. Plastics of the future The impact of biodegradable polymers on the environment and on society. Angewandte Chemie - International Edition. 2019 Nov 11;58(1):50–62.

80. Coutinho BC, Miranda GB, Sampaio GR, Souza LBS, Santana WJ, Coutinho HDM. Importance and advantages of polyhydroxybutyrate (biodegradable plastic). Holos. 2004; 76–81.

81. Zhou X, Li J, Wu Y. Synergistic effect of aluminum hypophosphite and intumescent flame retardants in polylactide. Polymer for Advanced Technologies. 2015 Nov 24;26(3):255–65.

82. Brockhaus S, Petersen M, Kersten W. A crossroads for bioplastics: Exploring product developers’ challenges to move beyond petroleum-based plastics. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2016 Jul 20;127:84–95.

83. Accinelli C, Mencarelli M, Balogh A, Ulmer BJ, Screpanti C. Evaluation of field application of fungiinoculated bioplastic granules for reducing herbicide carry over risk. Crop Protection. 2015 Jan;67:243–50.

84. Accinelli C, Abbas HK, Little NS, Kotowicz JK, Mencarelli M, Shier WT. A liquid bioplastic formulation for film coating of agronomic seeds. Crop Protection. 2016 Nov;89:123–8.

85. Accinelli C, Abbas HK, Shier WT. A bioplasticbased seed coating improves seedling growth and reduces production of coated seed dust. Journal of Crop Improvement. 2018 Jan 5;32(3):318–30.

86. Albanna M. Anaerobic digestion of the organic fraction of municipal solid waste. in Management of Microbial Resources in the Environment. 2013 (pp. 313– 40). Springer Netherlands, Heidelberg.

87. Cerda A, Artola A, Font X, Barrena R, Gea T, Sánchez A. Composting of food wastes: Status and challenges. Bioresource Technology. 2018 Jan;248(Part A):57–67.

88. Avidov R, Saadi I, Krassnovsky A, Hanan A, Medina S, Raviv M, et al. Composting municipal biosolids in polyethylene sleeves with forced aeration: Process control, air emissions, sanitary and agronomic aspects. Waste Management. 2017 Sep;67:32–42.

89. Costa MSS de M, Bernardi FH, Costa LA de M, Pereira DC, Lorin HEF, Rozatti MAT, et al. Composting as a cleaner strategy to broiler agro-industrial wastes: selecting carbon source to optimize the process and improve the quality of the final compost. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2017 Jan 20;142(4):2084–92.

90. Vázquez MA, Soto M. The efficiency of home composting programs and compost quality. Waste Management. 2017 Mar 18;64:39–50.

91. Alshehrei F. Biodegradation of Synthetic and Natural Plastic by Microorganisms. Journal of Applied & Environmental Microbiology. 2017;5(1):8–19.

92. Bastos Lima MG. Toward multipurpose agriculture: Food, fuels, flex crops, and prospects for a bioeconomy. Global Environmental Politics. 2018 May 15;18(2):143– 50.

93. Kaparapu J. Polyhydroxyalkanoate ( PHA ) Production by Genetically Engineered Microalgae : A Review. Journal on New Biological Reports. 2018 Aug 11;7(2):68–73.

94. Machmud MN, Fahmi R, Abdullah R, Kokarkin C. Characteristics of red algae bioplastics/latex blends under tension. International Journal of Science and Engineering. 2013 Oct 10;5(2):81–8.

95. Moroni M, Lupo E, Pelle V, Pomponi A, Marca F. Experimental Investigation of the Productivity of a Wet Separation Process of Traditional and Bio-Plastics. Separations. 2018 May 2;5(2):26.

96. Ringsmuth AK, Landsberg MJ, Hankamer B. Can photosynthesis enable a global transition from fossil fuels to solar fuels, to mitigate climate change and fuel-supply limitations Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 2016 Apr 6;62:134–63.

97. Patel VK, Soni N, Prasad V, Sapre A, Dasgupta S, Bhadra B. CRISPR–Cas9 system for genome engineering of photosynthetic microalgae. Molecular Biotechnology. 2019 May 28;61(8):541–61.

98. Green DS, Boots B, Sigwart J, Jiang S, Rocha C. Effects of conventional and biodegradable microplastics on a marine ecosystem engineer (Arenicola marina) and sediment nutrient cycling. Environmental Pollution. 2016 Oct 7;208:426–34.

99. Straub S, Hirsch PE, Burkhardt-Holm P. Biodegradable and petroleum-based microplastics do not differ in their ingestion and excretion but in their biological effects in a freshwater invertebrate gammarus fossarum. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2017 Jul 13;14(7):774.

100. González-Pleiter M, Tamayo-Belda M, Pulido- Reyes G, Amariei G, Leganés F, Rosal R, et al. Secondary nanoplastics released from a biodegradable microplastic severely impact freshwater environments. Environmental Science: Nano. 2019 Apr 4;6(5):1382–92.

101. Zuo LZ, Li HX, Lin L, Sun YX, Diao ZH, Liu S, et al. Sorption and desorption of phenanthrene on biodegradable poly(butylene adipate co-terephtalate) microplastics. Chemosphere. 2019 Oct 3;215:25–32.

102. Vasilakis MP, Puranen M, Supervisor V, Ogonowski M. A comparison between the effects of polylactic acid and polystyrene microplastics on Daphnia magna. Stockholms universitet. 2007;13.

103. Rochman CM, Hoh E, Hentschel BT, Kaye S. Long-term field measurement of sorption of organic contaminants to five types of plastic pellets: Implications for plastic marine debris. Environmental Science and Technology. 2013 Dec 27;47(3):1646–54.

104. Velzeboer I, Kwadijk CJAF, Koelmans AA. Strong sorption of PCBs to nanoplastics, microplastics, carbon nanotubes, and fullerenes. Environmental Science and Technology. 2014 Apr 1;48(9):4869–76.

105. Booij K, Robinson CD, Burgess RM, Mayer P, Roberts CA, Ahrens L, et al. Passive sampling in regulatory chemical monitoring of nonpolar organic compounds in the aquatic environment. Environmental Science and Technology. 2016 Nov 30;50(1):3–17.

106. Koelmans AA, Bakir A, Burton GA, Janssen CR. Microplastic as a vector for chemicals in the aquatic environment: critical review and model-supported reinterpretation of empirical studies. Environmental Science and Technology. 2016 Mar 7;50(7):3315–26.

107. Hartmann NB, Rist S, Bodin J, Jensen LHS, Schmidt SN, Mayer P, et al. Microplastics as vectors for environmental contaminants: Exploring sorption, desorption, and transfer to biota. Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management. 2017 Apr 25;13(3):488–93.

108. Álvarez-Chávez CR, Edwards S, Moure-Eraso R, Geiser K. Sustainability of bio-based plastics: general comparative analysis and recommendations for improvement. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2012 Oct 8;23(1):47–56.

109. Endres HJ, Siebert-Raths A, Endres HJ, Siebert- Raths A. End-of-life options for biopolymers. in Engineering Biopolymers. 2011 (pp. 225–243). Carl Hanser Verlag GmbH & Co. KG, Munich.

110. Hawkins WL. Polymer Degradation. 1984 (pp. 3–34). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

111. Shah AA, Hasan F, Hameed A, Ahmed S. Biological degradation of plastics: a comprehensive review. Biotechnology Advances. 2008 Jan 26;26(3):246–65.

112. Amass W, Amass A, Tighe B. A review of biodegradable polymers: uses, current developments in the synthesis and characterization of biodegradable polyesters, blends of biodegradable polymers and recent advances in biodegradation studies. Polymer International. 1998 Jul 10;47(2):89–144.

113. Song JH, Murphy RJ, Narayan R, Davies GBH. Biodegradable and compostable alternatives to conventional plastics. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Socciety B: Biological Sciences. 2009 Jul 27;364(1526):2127–39.

114. Kale G, Kijchavengkul T, Auras R, Rubino M, Selke SE, Paul Singh S. Compostability of bioplastic packaging materials: an overview. Macromolecular Bioscience. 2007 Mar 16;7(3):255–77.

115. Ahmed T, Shahid M, Azeem F, Rasul I, Ali Shah A, Noman M, et al. Biodegradation of plastics: current scenario and future prospects for environmental safety. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 2018 Jan 13;25(8):7287–98.

116. Itävaara M, Vikman M. An overview of methods for biodegradability testing of biopolymers and packaging materials. Journal of Environmental Polymer Degradation. 1996 Jan 1;4(1):29–36.

117. Lucas N, Bienaime C, Belloy C, Queneudec M, Silvestre F, Nava-Saucedo JE. Polymer biodegradation: mechanisms and estimation techniques. Chemosphere. 2008 Aug 23;73(4):429–42.

118. Balaguer MP, Aliaga C, Fito C, Hortal M. Compostability assessment of nano-reinforced poly(lactic acid) films. Waste Management. 2016 Nov 14;48:143–55.

119. Pagga U. Biodegradability and compostability of polymeric materials in the context of the European packaging regulation. Polymer Degradation and Stability. 1998 Jan 3;59(1-3):371–6.

120. Xiao B, Qin Y, Zhang W, Wu J, Qiang H, Liu J, et al. Temperature-phased anaerobic digestion of food waste: a comparison with single-stage digestions based on performance and energy balance. Bioresource Technology. 2018 Oct 26;249:826–34.

121. EN 13432: Packaging-requirements for packaging recoverable through composting and biodegradation. Test scheme and evaluation criteria for the final acceptance of packaging. European Comission. 2000.

122. Tokiwa Y, Calabia B, Ugwu C, Aiba S. Biodegradability of plastics. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2009 Aug 26;10(9):3722–42.

123. Singh B, Sharma N. Mechanistic implications of plastic degradation. Polymer Degradation and Stability. 2008 Nov 19;93(3):561–84.

124. Klein S, Dimzon IK, Eubeler J, Knepper TP. Analysis, occurrence, and degradation of microplastics in the aqueous environment. in Handbook of Environmental Chemistry. 2018 (pp. 51–67). Springer Verlag, Berlin.

125. Haider TP, Völker C, Kramm J, Landfester K, Wurm FR. Plastics of the future The impact of biodegradable polymers on the environment and on society. Angewandte Chemie - International Edition. 2019 Nov 11;58(1):50–62.

126. Nakanishi A, Iritani K, Sakihama Y, Ozawa N, Mochizuki A, Watanabe M. Construction of cell-plastics as neo-plastics consisted of cell-layer provided green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii covered by two-dimensional polymer. AMB Express. 2020 Jun 10;10(1):1–10.

127. Salguero DAM, Fernández-Niño M, Serrano- Bermúdez LM, Melo DOP, Winck FV, Caldana C, et al. Development of a Chlamydomonas reinhardtii metabolic network dynamic model to describe distinct phenotypes occurring at different CO2 levels. PeerJ. 2018 Sep 3:5528.

128. Wang B, Li Y, Wu N, Lan CQ. CO2 bio-mitigation using microalgae. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2008 Jul 1;79:707–18.

129. Moon M, Kim CW, Park WK, Yoo G, Choi YE, Yang JW. Mixotrophic growth with acetate or volatile fatty acids maximizes growth and lipid production in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Algal Research. 2013 Nov 13;2(4):352–57.

130. Sun H, Mao X, Wu T, Ren Y, Chen F, Liu B. Novel insight of carotenoid and lipid biosynthesis and their roles in storage carbon metabolism in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Bioresource Technology. 2018 May 10;263:450–57.

131. Ochoa-Méndez CE, Lara-Hernández I, González LM, Aguirre-Bañuelos P, Ibarra-Barajas M, Castro-Moreno P, et al. Bioactivity of an antihypertensive peptide expressed in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Journal of Biotechnology. 2016 Nov 2;240:76–84.

132. Lee H, Bingham SE, Webber AN. Function of 3’ noncoding sequences and stop codon usage in expression of the chloroplast psaB gene in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Molecular Biology. 1996 Mar 1;31:337–54.

133. Clair S, de Oteyza DG. Controlling a chemical coupling reaction on a surface: tools and strategies for on-surface synthesis. Chemical Reviews. 2019 Mar 15;119(7):4717–76.

134. Janica I, Patroniak V, Samorì P, Ciesielski A. Iminebased architectures at surfaces and interfaces: from selfassembly to dynamic covalent chemistry in 2D. Chemistry - An Asian Journal. 2018 Feb 8;13(5):465–81.

135. Payamyar P, King BT, Öttinger HC, Schlüter AD. Two-dimensional polymers: concepts and perspectives. Chemical Communications. 2016 Oct 19;52(1):18–34.

136. Sakamoto J, van Heijst J, Lukin O, Schlüter AD. Two-dimensional polymers: just a dream of synthetic chemists Angewandte Chemie - International Edition. 2009 Jan 28;48(6):1030–69.

137. Pilato L. Phenolic resins: 100 Years and still going strong. Reactive and Functional Polymers. 2012 Aug 10;73(2):270-7.

138. Markovic S, Dunjic B, Zlatanic A, Djonlagic J. Dynamic mechanical analysis strudy of the curing of phenol-formaldehyde novolac resins. Journal of Applied Polymer Science. 2001 Aug 22;81(8):1902-13.