Abstract

Background: Myocardial infarction (MI) leads to progressive left ventricular (LV) remodeling, significantly affecting patient outcomes and prognosis.

Objective: This paper provides a critical overview of the current standard of care and emerging pharmacological and regenerative therapies for prevention of cardiac remodeling post-MI.

Methods: We examined the effectiveness of conventional neurohormonal blockers, such as ACE inhibitors, ARBs, beta-blockers, and aldosterone antagonists, and their limitations, together with the evidence for new drug classes (ARNIs, SGLT2 inhibitors) and cell-based approaches. In particular, we focused on the progress in stem cell treatments, including mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), as well as the influence of bioengineering and biomaterials on the enhancement of drug delivery and retention.

Results: The current standard treatments reliably interact with the neurohormonal system but have barriers such as the incomplete blockade effect and side effects that limit their dosages. New drugs like ARNIs and SGLT2 inhibitors demonstrate superior outcomes due to their multimodal pathway targeting and improved heart metabolic function. In the field of regenerative medicine, there is a shift from the previously inconsistent approach of whole-cell implantation towards the widely accepted mechanism of using the paracrine effect of MSCs along with the application of highly advanced bioengineering techniques (cardiac patches, hydrogels, synthetic stem cells) to improve cell survival and targeted drug delivery, thus overcoming the problems of immunogenicity and poor engraftment. Additionally, the use of TGF-β inhibitors as one of the anti-fibrotic agents shows potential for the precision modulation of the extracellular matrix through research into anti-inflammatory and specific anti-fibrotic agents.

Conclusion: The future of attenuating adverse cardiac remodeling lies in a multimodal therapy paradigm. This therapeutic paradigm utilizes not only the optimized neurohormonal blockade together with the targeted anti-inflammatory, anti-fibrotic, and advanced engineered regenerative interventions, but also the complete and long-lasting preservation of LV structure and function after MI.

Keywords

Cardiac remodeling, Cardiovascular risk reduction, Cardiovascular therapeutics, Novel therapies

Contextual overview of myocardial infarction (MI) and cardiac remodeling

Acute myocardial infarction (MI) is a consequence of coronary artery occlusion in most cases, following plaque rupture [1]. It reduces the blood supply and eventually leads to myocardial necrosis. Cardiac remodeling follows this insult and involves molecular, cellular, and interstitial changes of the heart in size, shape, and function in response to injury [1,2].

Post-MI remodeling is bimodal. During the acute phase, necrosis triggers inflammation with subsequent action of macrophages and neutrophils leading to localized thinning and dilation of the infarcted myocardium [2]. The chronic phase further shows low-grade inflammation and neurohormonal activation by the sympathetic nervous system and Renin-Angiotensin- Aldosterone System (RAAS) that aims to induce hypertrophy, progressive ventricular dilation, and fibrosis, which continues to deteriorate cardiac function [2,3]. Although initially compensatory for cardiac output, over time these changes often give rise to heart failure, arrhythmias, and increased risk of sudden cardiac death.

Epidemiology and consequences of post-MI cardiac remodeling

Most survivors of MI develop post-MI cardiac remodeling, which commonly progresses to heart failure. This occurs in 30% of anterior MIs and 17% of non-anterior MIs [4]. Velagaleti et al. reported that almost 30% of patients develop heart failure within five years of MI [5]. The degree of remodeling is influenced by infarct location, reperfusion therapy, and concomitant comorbid conditions. Poor indicators that were noted are female sex and older age—both related to increased cardiac hypertrophy and reduced immune function [6]. Among diabetic patients, higher-risk individuals include females, as well as those with obesity, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and hypertension [7,8].

Cardiac remodeling leads to left ventricular dilation, wall thinning, and shape changes, impairing heart function [1,2]. These changes reduce left ventricular ejection fraction and increase the risk of heart failure, hospitalization, poor quality of life, and life-threatening arrhythmias [4,9]. Cardiac remodeling can also cause systemic complications such as renal dysfunction and pulmonary hypertension, exacerbated by neurohormonal activation. New therapies are needed to address or reverse remodeling [9].

Objectives and scope of the review

This narrative review highlights new treatments for the prevention or reduction of cardiac remodeling following myocardial infarction, including current and emerging pharmacological approaches, gene- and cell-based therapies, biomaterials, and mechanical support devices based on their mechanisms, efficacy, safety, and clinical outcomes. This review also discusses the implementation challenges in clinically applying these innovations.

Pathophysiology of Cardiac Remodeling Post-MI

Mechanisms underlying left ventricular remodeling

Myocardial infarction is followed by dynamic cardiac remodeling at the cellular, extracellular, and molecular levels [1–3]. Acute ischemic necrosis triggers cardiomyocyte loss initiating LV remodeling. This includes inflammation mediated through cytokines including Interleukin-6 (IL- 6) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), which recruit immune cells responsible for degradation of the ECM through metalloproteinases, thus further increasing inflammation [2]. While inflammation may be necessary for repair processes, excessive inflammation leads to injurious and detrimental remodeling with thinning of the LV and dilation [1,5,9].

Further compensatory mechanisms through the RAAS and sympathetic nervous system (SNS) promote fibrosis and apoptosis, causing chronic LV remodeling [10]. Angiotensin II, as a constituent of RAAS effector, increases cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and collagen deposition with matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) activity to foster myocardial fibrosis that impairs LV compliance [2,3]. Chronic activation of the SNS raises circulating catecholamines, enhancing cardiac hypertrophy and arrhythmogenesis [2,3]. The combined effects of overactivity in the RAAS and SNS lead to progressive LV dilation and deformation, impairing contractile efficiency and increasing heart failure risk [9]. ECM modification is critical; impaired ECM synthesis and breakdown result in excessive deposition of collagen, leading to increased arrhythmia risk and reduced compliance of the myocardium. This understanding is critical in developing therapies that halt or reverse remodeling [9].

Impact of cardiomyocyte death and myocardial necrosis

In pathological remodeling, cardiomyocyte death through necrosis and apoptosis contributes to myocardial damage. Necrosis caused by prolonged ischemia releases cellular contents, promoting the degradation of the extracellular matrix (ECM) and ventricular wall dilation leading to myocardial wall thinning and infarct enlargement [11].

The formation of peri-infarct regions with residual perfusion further aggravates this process by the infiltration of inflammatory cells such as macrophages and neutrophils, which further degrade the ECM and induce regional cardiomyocyte death. In contrast, autophagy may either exacerbate degeneration of the heart or protect it, depending on the factors modulating it.

Apoptosis and autophagy contribute to progressive atrophy of myocardial tissue and its dilation [12]. Reactive hypertrophy, accompanied by excessive fibrotic ECM deposition, also contributes to LV dilation and functional impairment. Biomechanical stress, inflammation, and activation of neurohormonal pathways are likely to result in interstitial fibrosis leading to programmed cardiomyocyte death, impairing ventricular cavity reconstructive function and increasing the risk of heart failure. Addressing these multiple mechanisms of cell death and myocardial necrosis requires targeted therapeutic strategies [13].

Progression to Heart Failure

Heart failure is a clinical syndrome in which the heart is unable to pump blood adequately to meet the body’s demands. The heart compensates for stress through mechanisms such as the Frank-Starling mechanism, ventricular remodeling, and neurohormonal activation, but these ultimately worsen heart failure [14]. Cardiac remodeling, as a structural change, is considered an essential pathway in the progression of HF, regardless of the underlying cause, including hypertension, myocardial infarction, cardiomyopathies, and diabetes. Acceleration of proteolytic enzyme activity such as matrix metalloproteinases, cathepsins, and caspases plays a major role in the remodeling process. A shift in the ratio of proteases to their endogenous inhibitors in hypertrophic and failing hearts increases proteolytic activity leading to remodeling [15].

Impact of mechanical unloading on cardiac remodeling processes

In recent years, mechanically assisted devices, particularly left ventricular assist devices (LVADs), have become a prominent treatment option for patients with heart failure [16]. Studies have shown that LVADs promote cardiac unloading and reverse remodeling. They improve cardiac energy metabolism, regulate calcium homeostasis, remodel cardiac tissue, and modulate immune responses. These changes contribute to myocardial recovery, including reduced fibrosis and improved contractility [17].

Morbidity and mortality associated with remodeling

Steroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs) such as spironolactone and eplerenone reduce mortality. Non-steroidal MRAs have high affinity and specificity for the mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) and demonstrate beneficial anti-inflammatory, anti-remodeling, and anti-fibrotic effects in the heart [18].

Both captopril and losartan were effective in preventing left ventricular (LV) dilation—a hallmark of adverse ventricular remodeling—compared with placebo treatment. However, reverse remodeling occurred only in the captopril-treated group. Despite this difference, the results suggest that the effects of these two drugs on LV remodeling alone do not justify a survival advantage for losartan over captopril [19].

Treatment with sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) improves LV systolic and diastolic function in patients with HFrEF (heart failure with reduced ejection fraction), particularly those taking empagliflozin, compared with other SGLT2 inhibitors [20]. Several clinical trials were reviewed to compare the effects of SGLT2i with a placebo in patients with heart failure (HF) or diabetes, using cardiac MRI (cMRI). Studies show that SGLT2i reduce LV mass compared with placebo, indicating potential to attenuate pathological myocardial hypertrophy [21].

Ventura shunt devices, which create a controlled left-to-right interatrial shunt, are safe, have produced favorable clinical outcomes in patients with HF, and support their potential as a therapeutic option. Improvements in left and right ventricular structure and function were consistent with reverse myocardial remodeling [22].

Predictive factors for detrimental remodeling

Elevated brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) levels—particularly >100 pg/mL—in the acute phase of MI are strongly associated with markers of myocardial injury and adverse changes in left ventricular geometry. A low aminoterminal propeptide of type III procollagen to type I collagen telopeptide ratio at 1 month post-MI may further reflect maladaptive remodeling. Together, these biomarkers are linked to an increased risk of cardiovascular death or recurrent hospitalized myocardial infarction within 3 years of the initial event. Additionally, studies suggest that administration of recombinant human B-type natriuretic peptide may improve cardiac function by modulating neurohormonal activity and supporting ventricular recovery [23].

Higher levels of hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) were associated with markers of stress and inflammation such as BNP and C-reactive protein (CRP). Patients with higher HGF concentrations were more often readmitted for HF or died during the course of the year. This implies that HGF could be a potential biomarker of poor heart recovery, and high risk after myocardial infarction [24].

Both the IL-6 and TNF-alpha levels were significantly elevated in the patients with MI in the acute phase as compared to the controls [25]. Sclerostin (SOST), growth differentiation factor 15 (GDF-15), urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA), and midkine (MK) biomarkers are upregulated in MI patients who develop cardiac remodeling while monocyte chemotactic protein 3 (MCP-3) biomarker is down-regulated. In particular, the two proteins uPA and MK were newly linked to cardiac remodeling [26].

Current Standard of Care in Preventing Cardiac Remodeling

Pharmacological interventions: ACE inhibitors, ARBs, beta-blockers, and aldosterone antagonists

The cornerstone of current therapy for preventing cardiac remodeling includes pharmacological interventions such as ACE inhibitors, ARBs, beta-blockers, and aldosterone antagonists. ACE inhibitors (e.g., enalapril) have demonstrated significant benefits in reducing mortality and attenuating ventricular dilation by lowering angiotensin II levels, thereby decreasing vasoconstriction, and sodium retention [27]. ARBs (e.g., losartan) serve as an alternative for patient’s intolerance to ACE inhibitors, providing similar cardioprotective effects by selectively blocking the angiotensin II receptor [28]. Beta-blockers (e.g., carvedilol, metoprolol) mitigate sympathetic overactivity, reduce myocardial oxygen consumption, and improve overall cardiac function [29]. Aldosterone antagonists (e.g., spironolactone) reduce sodium retention and fibrosis, further aiding in preventing remodeling [28].

Limitations of existing therapies

These effective therapies are associated with several limitations. ACE inhibitors and ARBs suppress the RAAS, however residual remodeling may persist due to incomplete inhibition. Adverse effects such as hyperkalemia, hypotension, and renal dysfunction limit their use in certain populations [30]. Beta-blockers may not be well-tolerated due to bradycardia or fatigue, and aldosterone antagonists can lead to hyperkalemia and renal impairment, especially in patients with pre-existing kidney disease [31]. More targeted therapies need to be developed to effectively address the multifactorial nature of cardiac remodeling. Table 1 summarizes various previous studies investigating therapies for cardiac remodeling post-MI.

|

Study |

Study Type |

Study Population |

Intervention |

Duration |

Positive Outcome |

Negative Outcome |

Key Findings |

|

Wollert et al. (2004) [32] |

Randomized Controlled Trial |

60 patients post-acute STEMI |

Intracoronary transfer of autologous bone marrow cells. |

6 months |

Significant improvement in LVEF (6.7% vs. 0.7%, p=0.0026) |

No increase in adverse clinical events. |

Bone marrow cell transfer improved LVEF in post-MI patients without adverse events. |

|

Hirayama et al. (2005) [33] |

Prospective Cohort |

45 patients with first AMI |

BNP measured from aorta and anterior interventricular vein at 1,6 and 18 months. |

18 months |

BNP levels at 1 month predicted adverse LV remodeling at 18 months. |

No significant difference in LV function at 1 month, however plasma BNP was higher in remodeled group (p<0.01). |

BNP levels predicted LV remodeling before it became evident, making it an early marker of adverse outcomes. |

|

Kuethe et al. (2005) [34] |

Prospective, Non-Randomized |

AMI patients treated with PCI, 14 G-CSF, 9 controls |

G-CSF (5 μg/kg/day for 4 days) |

3 months |

Improved regional wall motion, wall perfusion, LVEF. |

No significant adverse events, small cohort is limitation. |

G-CSF improved LVEF and wall motion in AMI patients; safe in the treated population. |

|

Kang et al. (2008) [35] |

Meta Analysis and Systematic Review |

517 patients with acute MI |

Intracoronary infusion of autologous bone marrow cells |

6 and 12 months post-MI |

Improved LV function. |

Adverse effects were not significantly different than control group. |

Autologous bone marrow cells positively impacted LV function post-MI. |

|

Gian luigi nicolosi et al. (2009) [36] |

Randomized, Multicenter Clinical Trial |

1252 elderly post-AMI patients with preserved LV function |

Perindopril 8 mg/day vs placebo |

1 year |

Perindopril reduced progressive LV remodeling and maintained LVEDV (P<0.001). |

Patients with smaller LV cavity size and greater dyssynergy were more prone to remodeling. |

Perindopril significantly reduced LV remodeling in elderly post-AMI patients with preserved LV function. |

|

Assmus et al. (2010) [37] |

Clinical |

204 patients with acute MI |

Intracoronary infusion of bone marrow-derived progenitor cells |

2 years post-MI |

Improved LVEF and regional contractility (P=0.025). |

Limited retention of infused BMC in myocardium. |

Bone marrow-derived progenitor cells significantly improved LVEF and regional contractility in MI patients. |

|

Weir et al. (2011) [38] |

Randomized, Double-blind Trial |

93 patients with LV dysfunction after acute MI (no HF) |

Eplerenone vs placebo for 24 weeks |

24 weeks |

Baseline aldosterone predicted remodeling; Eplerenone attenuated remodeling in aldosterone group. |

No significant correlation of biomarkers in Eplerenone group. |

Eplerenone effectively reduced LV remodeling linked to elevated aldosterone and cortisol in the placebo group. |

|

Gao et al. (2015)[39] |

Clinical |

116 patients with acute STEMI |

Intracoronary infusion of Wharton's jelly-derived MSCs |

4 and 18 months post-MI |

Improved myocardial viability, LVEF, and LV volumes compared to control (P=0.0004). |

Effect on reducing infarct size is modest. |

Wharton's jelly-derived MSCs significantly improved cardiac remodeling post-MI, offering a promising regenerative therapy. |

|

Van der velde et al. (2015)[40] |

Prospective Cohort |

247 subjects from an RCT with acute MI undergoing PPCI |

Plasma galectin-3 and s-ST2 measured at baseline and 4 months |

4 months |

Higher baseline galectin levels predicted lower LVEF and larger infarct size at 4 months. |

Galectin levels at 4 months lost predictive value. |

Baseline galectin, not s-ST2, independently predicted LV dysfunctional remodeling and infarct size. |

|

Kim et al. (2018)[41] |

Clinical |

26 participants with acute anterior wall STEMI |

Intracoronary infusion of 7.2±0.90 ×107 autologous MSCs |

4 and 12 months post-MI |

LVEF significantly improved compared to control after 4 (p =0.023) and 12 months (p=0.048) post-MI. |

LVEDV did not decrease despite improved LVEF. |

Autologous MSCs improved cardiac function post-MI. |

|

Felice achilli et al. (2019)[42] |

Clinical |

161 ST-segment elevation MI patients |

SOC (STEM-AMI OUTCOME CMR Substudy) vs. SOC + granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) |

6 months and 2 years |

G-CSF preserved LV function (P=0.01), reduced scar size, and prevented adverse LV remodeling. |

No placebo arm in trial. |

G-CSF provides cardioprotection in STEMI patients, supporting it as an adjunct therapy. |

|

Zhao et al. (2021)[43] |

Meta-analysis |

6154 Acute MI patients from 4 studies |

Sacubitril/Valsartan vs ACEI (plus standard care) |

41 months |

LVEF significantly higher (P=.000), and major adverse cardiac events lower in Sacubitril/Valsartan group (P=.001). |

No significant difference in cardiac death, HF hospitalization. |

Sacubitril/Valsartan improved LVEF and reduced major adverse cardiac events compared to ACEI, providing better protection against cardiac remodeling. |

|

Broch et al. (2021)[44] |

Randomized Double-Blind Trial |

199 patients with acute STEMI |

Single infusion of tocilizumab vs. placebo |

3–7 days |

Larger myocardial salvage index in the tocilizumab group. |

Absolute effect on myocardial necrosis was smaller than anticipated. |

Tocilizumab improved myocardial salvage, though infarct size did not differ significantly. |

|

Jing wang et al. (2023) [45] |

Randomized Clinical Trial |

200 AMI patients post-PCI |

Azilsartan vs. Benazepril |

6 months, 1 year |

Azilsartan significantly reduced LVEDV and improved myocardial remodeling. |

Effectiveness declined over time. |

Azilsartan showed positive effects on cardiac remodeling within 6 months post-MI, with CTRP1 as a target for prevention of adverse remodeling. |

|

Tezcan et al. (2023) [46] |

Clinical |

Patients with acute MI |

Candesartan treatment vs. zofenopril |

6 months post-MI |

Significant reduction in LV mass and LVMI in the candesartan group. |

None reported. |

Candesartan showed more prominent benefits in improving cardiac remodeling compared to zofenopril. |

Emerging Pharmacological Therapies

Innovative drugs targeting neurohormonal pathways

Recent advances in pharmacotherapy have introduced novel drugs targeting neurohormonal pathways. Angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitors (ARNIs), such as sacubitril/valsartan, combine the benefits of RAAS inhibition with neprilysin inhibition, increasing the levels of beneficial natriuretic peptides. This dual action enhances vasodilation, reduces cardiac stress, reduces heart failure hospitalizations, and cardiovascular mortality more effectively than ACE inhibitors alone [47]. Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, initially developed for diabetes management, have demonstrated benefits in reducing heart failure events, likely due to their diuretic effects and ability to improve myocardial metabolism and reduce cardiac workload [48].

Role of anti-inflammatory agents in remodeling mitigation

According to recent studies, inflammation has a crucial role in the process of cardiac remodeling. Anti-inflammatory therapies are being developed as valuable adjuncts in heart failure therapy. Colchicine is an anti-inflammatory drug that is widely used in the treatment of gout and was also proven to reduce inflammatory markers and adverse cardiovascular events in coronary artery disease [49]. Canakinumab is another monoclonal antibody targeting Interleukin-1β, which has demonstrated a significant reduction of cardiovascular events as per the CANTOS trial. Direct evidence connecting these treatments to structural remodeling remains under investigation, nevertheless, these findings highlight the critical role of inflammation in cardiovascular disease. In addition to standard therapies, addressing the inflammatory component may improve clinical outcomes in patients with heart failure and following MI [50].

Stem cell-based therapies

MI is characterized by a substantial loss of cardiac myocytes in the acute phase [36] and is followed by progressive ventricular remodeling over subsequent months [51]. Hence, stem cells serve as a viable alternative for cell regeneration. Stem cells are undifferentiated cells with self- renewal properties that differentiate into multiple types of cells [52]. They can be human embryonic stem cells (ESC) or adult stem cells, which includes hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) and mesenchymal stem cells (MSC). MSCs further differentiate into lineage specific progenitor cells, such as, skeletal myoblast (SM), endothelial progenitor cells (EPC), etc [52]. However, inconsistent results and challenges such as immunogenicity, tumorigenicity, lower rates of survival and engraftment [53,54] and a growing body of evidence suggesting a paracrine mechanism of action rather than direct differentiation have led to a paradigm shift towards acellular therapies [55]. Table 2 provides a brief overview of the types of stem cells, their salient features and a summary of some significant clinical trials and their outcomes.

|

Type |

Salient features |

Mechanism |

Significant Clinical trials and outcome |

||

|

Trial |

Unique aspects of intervention |

Conclusion |

|||

|

Skeletal myoblast |

Properties similar to cardiac muscle except in electrical aspects, high resistance to ischemia insults, limited by their inability to differentiate into cardiac myocytes. |

Emphasis on paracrine and cardioprotective aspects rather than regeneration. |

Magic Menasché et al. [59] |

First clinical trial of cell therapy to prevent remodeling. |

LVEF did not improve like in animal models and arrythmia was a major adverse effect. |

|

Bone Marrow Mononuclear Cells |

Most commonly used cell type, heterogenous cell population factors in difficulty isolating subtypes and also in inconsistencies in results. |

Ability to differentiate into cardiomyocytes is still unclear, paracrine mechanisms widely elucidated, also has unique homing feature to sites of injury. |

Strauer et al. [61] |

First clinical trial that included BMMNCs, assessed safety and efficacy. |

No adverse events reported. |

|

|

|

|

BOOST - Meyer et al. [63] |

Assessed both short term and long-term outcomes. |

LVEF showed a short-term improvement at 6 months, which disappeared by 18 months. |

|

|

|

|

ASTAMI - Lunde et al. [99,100] |

Included assessment of quality of life at 6 months. |

LV function and quality of life did not improve at follow up. |

|

|

|

|

REPAIR-AMI Schächinger et al. [64] |

Assessment of timing of intervention and follow up at 2 years. |

Cell therapy at 5 days or more after PCI was associated with better outcome than cell therapy at 4 days or less. Also, LVEF improvement persisted at 2 years follow up. |

|

|

|

|

SWISS-AMI - Sürder et al. [65] |

Timing of intervention [5–7 days before or 3–4 weeks post PCI. |

No improvement in LV functioning irrespective of timing of intervention at 12 months. |

|

|

|

|

TIME – Traverse et al. [66] |

Timing of intervention at day 3 or day 7 post-PCI. |

No improvement in LV functioning irrespective of timing of intervention, also 2 years follow up resulted in the same results. |

|

|

|

|

Late TIME - Traverse et al. [67] |

Timing of intervention at 2–3 weeks post PCI. |

No improvement in LV functioning at 6 months. |

|

|

|

|

Clifford et al. [101] |

Metanalysis of association of LVEF and morbidity/mortality. |

Although BMMNC therapy improved LVEF at follow up [12–61 months], it was not associated with decrease in morbidity/mortality. |

|

|

|

|

Zhang et al. [68] |

Meta-analysis that included effect dose and time of intervention apart from LV parameters. |

LV functioning improved only at 6–12 months and did not persist till 18–48 months. Dose of 10–100 million cells and intervention between 2–7 days post-PCI was most beneficial. |

|

|

|

|

BAMI - Mathur et al. [69] |

Assessed safety and efficacy of BMMNC at reducing all-cause mortality. |

Unsuccessful due to low recruitment rates, which prevented meaningful analysis. The existing data demonstrated only slight clinical benefit. |

|

|

|

|

Hosseinpour et al. [102] |

Comparison of therapeutic efficiency BMMNC versus MSC cells. |

LVEF improved in both groups, however MSC was more effective. |

|

|

|

|

Hosseinpour et al. [70] |

Metanalysis of rate of hospitalizations due to CHF. |

AMI patients treated with BMMNCs were less likely to be hospitalized due to CHF, however it was not associated with any changes in all-cause mortality rate. |

|

|

|

|

Attar et al. [71] |

Meta-analysis on MACE rates in patients treated with BMMNCs. |

There was decrease in rate of hospitalization due to CHF and reinfarction, but no effect was found on rate of cardiovascular death. |

|

Hematopoietic stem cells |

Multipotent stem cells that differentiate into blood cells, uncertain efficacy and safety due to limited studies and inconsistent results. |

Fuse with the resident cardiomyocytes rather than differentiation into cardiac cells. |

REGENT - Tendera et al. [85] |

Comparison of therapeutic efficiency of BMMNCs Vs CD34+ HSC. |

No significant difference in improvement in LV function was reported between the two groups. |

|

|

|

|

Seth et al. [86] |

Systematic review of 7 studies assessing the use of HSCs in ischemic HF patients. |

HSCs therapy was associated with an improvement in LV function, perfusion. Also, the rate of rehospitalization, death and reinfarction was lower among HSCs treated group. |

|

Endothelial Progenitor cells |

Unipotent progenitor cells [CD34+, CD31+, CD133+] that differentiate into endothelial cells.

|

Promote neovascularization and induce migration of mature endothelial cells via paracrine mediators. |

IMPACT-CABG - Noiseux et al. [82] |

CD133+/CD34+/CD45+ EPCs were transplanted into patients with chronic ischemic cardiomyopathy. |

No significant improvement in LVEF at 6 months follow up and also no reports of adverse events. |

|

|

|

|

COMPARE-AMI - Mansour et al. [83] |

CD133+ were used and assessed safety and efficacy. |

CD133+ therapy was safe and there was improvement in LVEF at 4 months and 12 months. |

|

|

|

|

Haddad et al. [84] |

Long term follows up of COMPARE trial patients to assess safety and efficacy. |

Treatment with CD133+ cells was safe. However, no significant difference was noted in the survival rate between the control and treatment group at a median follow up of 8.5 years. |

|

Mesenchymal stem cells |

Multipotent stem cells easily derived and expanded from various sources [Bone marrow, Umbilical cord blood, Wharton's jelly, Adipose], allogenic potential due to immune privilege. |

paracrine secretion leading to angiogenesis, immunomodulation. Extracellular vesicles contain bioactive molecules INCLUDING miRNA, GF, cytokines. |

PROCHYMAL - Hare et al. [103] |

Safety and efficacy of MSCs transplantation. |

MSC therapy was safe. |

|

|

|

|

POSEIDON - Hare et al. [77] |

Effect of Allogenic MSCs Vs Autologous MSCs. |

Allogenic MSC transplantation was safe, improvement of LV function in both groups with no significant difference between them. |

|

|

|

|

Suncion et al. [104] |

Effect of MSCs at local injection and remote myocardial segments. |

Scarred segments showed reduction in scar at both sites, contractility improved significantly at local site only. Non scarred segments did not show any difference. |

|

|

|

|

C-CURE - Bartunek et al. [105] |

MSCs modified by cardiopoietic lineage specification. |

Modified MSCs therapy was safe, decrease in LVESV and increase in 6MWD. |

|

|

|

|

PRECISE - Perin et al. [72] |

Safety and efficacy of Adipose derived MSCs. |

Safe and feasible at 6 and 18 months. |

|

|

|

|

Gao et al. [39] |

Safety and efficacy of Wharton's Jelly derived MSCs. |

Safe and feasible. Improvement in LVEF at 18 months. |

|

|

|

|

Fu & Chen [78] |

Meta-analysis of 6 RCTs with 625 patients with heart failure. |

MSC therapy had no effect on cardiovascular death, Improvement in LVEF and decreased rehospitalization rates with no effect on rat of MI, HF recurrence or total death. |

|

|

|

|

Attar et al. [79] |

Meta-analysis of 13 RCTs with 956 patients, evaluated timing, dosing and delivery route. |

Increase in LVEF, amplified by timing of intervention being the first week after AMI and dose being 107 cells. NO significant difference between trans endocardial and intracoronary route . |

|

|

|

|

Yu et al. [80] |

Meta-analysis of 9 RCTs with 460 patients, evaluated timing, dosing and MACE rate. |

Increase in LVEF persisting till 24 months, optimal dose being 107–108 cells and timing being 2–14 days post PCI. No difference in MACE rate or rehospitalization. |

|

|

|

|

Krishna Mohan et al. [106] |

14 RCTs with 1445 patients. |

Improvement in LVEF and rehospitalization rates, no effect on outcomes of cardiovascular death, recurrence of HF. |

|

Embryonic Stem Cells |

Pluripotent, differentiates into any type of adult cell, ethical, social concerns. |

Differentiates into cardiac cells and couples electrochemically to adjacent cells. |

ESCORT - Menasché et al. [88] |

Human ESCs integrated into a patch and transplanted into IHD patients undergoing CABG. |

Safety was established, novel drug delivery mechanism using a patch. |

|

Cardiac Stem Cells |

Endogenous stem cell population, hence superior cardiac differentiation, limited by availability, identification and isolation. |

Unclear mechanism regarding differentiation, immunomodulatory properties investigated. |

CADUCEUS - Makkar et al. [96] |

Cardiosphere cells CDCs transplantation. |

Significant scar size reduction was reported despite lack of functional (LVEF) improvement. There were also concerns regarding adverse events |

|

|

|

|

CAREMI - Fernández-Avilés et al. [97] |

Safety of Allogenic CSCs transplantation. |

No death or MACE at 12 months, no improvements in LV function or infarct size at 12 months. |

|

|

|

|

ALLSTAR - Makkar et al. [98] |

Safety of Allogenic CDCs transplantation. |

Left ventricular volumes and cardiac biomarkers reduced. However, no improvement in scar size. |

Skeletal myoblasts and bone marrow mononuclear cells

Skeletal myoblasts were the first stem cells to be used for regenerative therapy [56]. Despite inconsistent results in preclinical studies [57,58], a large RCT, MAGIC [59], failed to show any benefits and moreover reported arrhythmias.

Bone marrow derived cells were the next target and have been extensively studied. Micheu et al. [60], explains the timeline of these stem cells therapy in myocardial infarction. Initial clinical studies demonstrated the safety of Bone Marrow-derived Mono-Nuclear Cells (BMMNCs) [61,62]. However, the benefits on LV functioning on short-term and long-term have been inconsistent. BOOST trial [63], demonstrated only short-term benefits at 6 months, whereas REPAIR-AMI [64] reported benefits up to 2 years. The inconsistencies piled on with three more trials SWISS-AMI [65], TIME [66], and LateTIME [67] concluding with no improvement in LV remodeling irrespective of the timing of the intervention. Recently, 2 year long-follow-up of patients of TIME trial also showed no benefits [66].

However, a meta-analysis revealed improvement in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) at 6–12 months, with maximum benefit by transplantation between 2–7 days and a dose of 10–100 million cells, but the effect disappeared at 18–48 months [68]. Unfortunately, significant conclusions about all-cause mortality could not be drawn from the largest RCT—BAMI, due to low recruitment [69]. However, two recent meta-analyses revealed a decrease in long term rehospitalization rate, although there was no association between treatment and all-cause mortality [70,71].

Mesenchymal stem cells, endothelial progenitor cells and hematopoietic stem cells

MSCs are gaining immense popularity due to their ease of extraction and rich sources [39,72,73]. Adipose derived MSCs and Wharton Jelly derived MSCs have proven to be safe [39,72] and the latter also improved LVEF at 18 months [39]. MSCs contribute mainly by paracrine mechanism by secreting extracellular vesicles which contain biomolecules that promote angiogenesis [74], suppress inflammation, increase survival and decrease apoptosis [75,76]. They also have immunomodulatory properties with potential for allogeneic use [77].

A meta-analysis of MSC therapy in heart failure patients showed improvement in LVEF and rehospitalization rate, with no effect on recurrence of heart failure, cardiovascular or all-cause mortality [78]. Two more meta-analyses showed maximum benefit with 107 or 107–108 cells transplanted in the first week after acute myocardial infarction (AMI) or 2–14 days post percutaneous intervention (PCI) [79,80], with no difference in trans-endocardial or intracoronary route [79].

EPCs promote neovascularization in the injured myocardium [81]. Two clinical trials, IMPACT-CABG and COMPARE-AMI proved the safety of EPCs with IMPACT-CABG showing no significant changes in LVEF and COMPARE-AMI showed an improvement in LVEF at 12 months, which did not persist on long term follow up (mean 8.5 years) [82–84].

The benefits of HSCs have been inconsistent due to the limited number of trials. Contradictory to the REGENT [85] trial showing no benefits, a 2024 systematic review of 7 studies assessing HSC therapy in heart failure showed an improvement in LV function [86].

Embryonic stem cells, induced-pluripotent stem cells and cardiac stem cells

ESCs are stem cells derived from inner cell mass of an embryo and are considered superior due to their electrical coupling with the heart [87]. The 2015 ESCORT trial [88] showed ESCs transplantation in IHD patients to be safe and improved LV parameters at 3 months follow up. The issue of ethical concerns of using ESCs is addressed by Induced-Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs), which are stem cells generated from endogenous somatic cells by reprogramming [89]. Despite mixed preclinical results [90], and the risk of tumorigenicity [91] and immunogenicity [92], iPSCs offer superior differentiation into cardiomyocyte due to the ability to differentiate into any type of cardiac cell. More robust, large-scale studies have to be conducted to evaluate the safety and efficacy of iPSCs.

Cardiac stem cells (CSCs) are heterogenous populations of stem cells with superior differentiation ability into adult cardiac cells compared to other stem cells and their potential for allogeneic use [93,94]. A major challenge is isolating this subset of cell population from tissues. Various surface markers which supposedly identify these stem cells, like c-KIT, SCA-1(Stem cell antigen-1), SP (Side population-Abcg2), Isl-1 (Homebox gene Islet-1) and others have been used [93,95]. Clinical trials like SCIPIO [94], CADUCEUS [96], CAREMI [97] and ALLSTAR [98] have proved the therapy to be safe. SCIPIO showed c-KIT+ CSCs improved cardiac functioning, but the paper was retracted [94]. However, the CADUCEUS trial and CAREMI trial failed to report any such improvement [96,97]. The ALLSTAR trial however showed a decrease in LV volumes at 6 months [98].

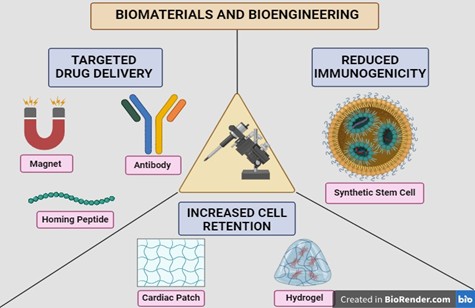

Biomaterials and bioengineering

Conventional stem cell-based therapies are riddled with challenges such as isolation and manufacturing [107], invasive delivery process [108], low engraftment and survival rates [53], as well as immunogenic and tumorigenic potential [55]. Biomaterials and bioengineering offer some potential solutions, which are described in the context of these limitations.

Targeted drug delivery – antibodies, magnets and homing peptides

Bispecific antibodies are antibodies that can simultaneously bind to two different antigens. Preclinical studies have utilized these antibodies by targeting specific stem cells and injured myocardium to achieve targeted delivery [109]. However, the use of antibodies may lead to an immune response, which may be a limitation.

An FDA approved magnetic nanoparticle Ferumoxytol, was used to label Cardiosphere-Derived Cells (CDCs), which resulted in higher cell retention [110]. Equipment safety may be a concern when using magnets [55].

Vandergriff et al., employed a peptide known as cardiac homing peptide-CHP, conjugated to exosomes derived from CDCs, resulting in increased uptake and viability, decreased apoptosis in vitro and improved LV functioning in vivo [111]. In another study, a peptide targeting a subunit of L-type calcium channel of cardiomyocytes was conjugated with Calcium Phosphate nanoparticles as a novel drug delivery mechanism via inhalation [112].

Increasing cell retention—cardiac patches

Cardiac patches are platforms used to deliver cells or their products. Based on the source, they can be either natural (collagen, fibrin, gelatin, alginate, chitosan, hyaluronic acid) or synthetic, such as polylactide-co-glycolide (PLGA). Additionally, patches can be cellular and acellular based on their contents [113].

Furthermore, cellular patches can either be sheets or scaffolds. Use of uni-layered myocardial cell sheets developed initially [114], were limited due to insufficient vascular growth, prompting the development of multi-layered cell sheets made of human-iPSCs with embedded endothelial cells with better engraftment [115]. Scaffolds contain cells suspended in a biomatrix made of natural or synthetic polymers. They vascularized better because of lesser resistance offered to invasion, and can be primed with growth factors [116]. Recently, a sandwich model of human-iPSC derived endothelial cells between two layers of human-iPSCs showed better cell engraftment in rats [117]. Pre-vascularized grafts containing engineered micro vessels also offer a novel approach [118]. A clinical trial using a pericardial matrix patch with human Wharton Jelly- Mesenchymal Stromal Cells concluded with reduction in scar mass [119].

Acellular patches release loaded bioactive molecules or provide mechanical support to improve LV contractility [120]. Acellular patches per se can also induce regeneration as observed by a porcine heart-based d-ECM which induced cardiac regeneration by recruiting cardiac progenitor cells in rat models [121]. Polycaprolactone (PCL), a synthetic polymer containing Nitric Oxide (NO) [122] improved cardiac function and attenuated remodelling [122]. Recently, a synthetic patch made of GelMA (Gelatin methacryloyl) loaded with Galunisertib, a TGF-B inhibitor [123], decreased fibrosis in rat MI models.

Increasing cell retention—hydrogels

Hydrogels are natural or synthetic polymer networks which act as controlled release and delivery vehicles due to their phase transition and responsiveness to external triggers [113].

Multiple preclinical studies have demonstrated its benefits such as BM-MSCs delivered via chitosan polymer [124], human adipose derived stem cells (hADSCs) delivered via Gelatin-Collagen and Transglutaminase crosslinked hydrogel [125]. Hydrogels can also deliver bioactive molecules such as growth factors—HGF [126], Fibroblast Growth Factor (FGF) [127], Platelet Derived Growth Factor (PDGF) [128], and Micro-RNAs—miRNA-29B [129]. Synthetic hydrogels such as Polypyrrole or Tetraaniline also conduct electricity, which improves electrical signal propagation in the scar tissue of a rat myocardial infarction (MI) model [130,131]. AUGMENT-HF, a clinical trial where alginate hydrogel was implanted in patients with advanced heart failure improved the exercise capacity at 6 months which sustained through 1 year [132]. Another clinical trial demonstrated the safety of hydrogel containing human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells in patients with chronic ischemic heart disease [133]. Hydrogel delivery usually requires an invasive approach, however in 2019, a clinical trial demonstrated the safety and feasibility of VentriGel, a porcine heart decellularized extracellular matrix hydrogel delivered via percutaneous trans endocardial injection [134].

Reducing immunogenicity—synthetic stem cells

Tang et al., developed a novel approach by artificially synthesizing bioparticles called cell mimicking microparticles—CMMPs [55]. It consists of a synthetic polymer backbone PLGA [135], loaded with the secretory component of stem cells, forming a microparticle. It was then coated with the cell membrane of cardiomyocytes to make it more biocompatible. These CMMPs functioned as synthetic stem cells, which did not evoke an immune reaction when transplanted into mice [136]. Another trial employing CMMPs with the membrane coat derived from bone marrow-MSC demonstrated the stability of these cells in terms of cryopreservation and lyophilization [137]. Subsequently, Huang et al., developed a porcine decellularized myocardial extracellular matrix scaffold and colonized it with synthetic cardiac stromal cells [138]. In addition to improved cardiac function in animal models, it was suggested to be an ‘off-the-shelf’ product due to its stability and potency after cryopreservation [138]. In another preclinical study by Yao et al., a silica nanoparticle loaded with mi-R21 (microRNA 21) coated with MSC membrane improved the cardiac function and escaped an immune reaction [139]. Figure 1 summarizes solutions offered by biomaterials and bioengineering.

Figure 1. Biomaterials and Bioengineering.

Targeted molecular therapies: Small molecule inhibitors of signaling pathways

Targeted molecular therapies aim to modulate specific signaling pathways implicated in cardiac remodeling. One such strategy focuses on controlling fibrosis and tissue damage through small molecule inhibitors targeting the Transforming Growth Factor Beta (TGF-β) pathway, a promising method for inhibiting pathological remodeling. TGF-β is a key regulator of fibrosis, making it an attractive target for therapeutic intervention. Among the TGF-β receptor inhibitors that have shown substantial success in preclinical models is galunisertib, which has demonstrated the ability to reduce fibrosis and hypertrophy [140]. Animal studies suggest that inhibiting TGF-β improves cardiac function, as indicated by a reduction in LV mass and improved contractile performance. These findings offer hope for precision medicine in patients with cardiac remodeling. However, the complexity of signaling networks and the potential for off-target effects necessitate further research to fully optimize the therapeutic use of these inhibitors.

Antifibrotic agents: Agents potentially capable of reversing remodeling

Antifibrotic drugs are among the few interventions with the potential to halt or reverse cardiac remodeling. One of the primary targets of these drugs is cardiac fibrosis, which leads to myocardial stiffening. Drugs like nintedanib and pirfenidone, initially developed for pulmonary fibrosis, are currently under investigation for their ability to reduce fibrosis in heart tissue. These drugs improve heart function by reducing collagen deposition and inhibiting fibroblast proliferation [141]. Additionally, pirfenidone has been shown to decrease fibrosis by suppressing the expression of pro-fibrotic markers such as collagen I and fibronectin. Although further clinical studies are required to fully assess their long-term efficacy in heart disease, early findings suggest that these drugs hold promise [142]. Interestingly, preclinical models indicate that antifibrotic drugs may enhance the effects of heart failure treatments, such as ACE inhibitors, in reducing adverse remodeling.

Immunomodulatory approaches: Role of immune modulation in adverse remodeling prevention

Immune regulation is a key therapeutic strategic for mitigating the negative effects of cardiac remodeling. Chronic inflammation, triggered by inflammatory responses following cardiac damage, can exacerbate remodeling and promote fibrosis. Interleukin-1 (IL-1) inhibitors, such as anakinra, have been shown to reduce inflammation and the subsequent remodeling process [143]. These therapies work by blocking IL-1, reducing the release of other inflammatory mediators such as TNF-α and IL-6, which are known to worsen myocardial damage. Clinical studies have demonstrated that anakinra leads to significant reductions in CRP, a biomarker of inflammation, suggesting that it may help prevent long-term remodeling. Additionally, modulating immune responses, particularly macrophage activity, can further promote healing and improve outcomes [143]. By modifying the inflammatory environment, these therapies aim to prevent long-term damage and support heart repair [50].

Mechanical circulatory support devices: Ventricular assist devices in severe remodeling management

For patients with end-stage heart failure, ventricular assist devices (VADs) play a crucial role in managing severe remodeling. VADs provide partial reverse remodeling and improve hemodynamics by reducing the heart's workload. Extended support from VADs has been associated with improvements in myocardial function and a reduction in left ventricular size [144]. Moreover, VADs help improve neurohormonal balance, as evidenced by decreased levels of brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), indicating reduced cardiac chamber stress [145]. Specifically, in dilated cardiomyopathy, VADs contribute to myocardial unloading, which may promote the heart's intrinsic healing. While VADs are often used as a bridge to transplantation or as destination therapy, they do not eliminate the need for heart transplantation. Despite this, they have significantly improved both survival rates and quality of life for patients with severe heart failure [145]. Additionally, transient mechanical support devices like intra-aortic balloon pumps are being explored for acute conditions requiring short-term unloading.

The use of Impella, a percutaneous ventricular assist device, has gained substantial attention for managing acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock (AMICS). Impella directly unloads the left ventricle, ensuring adequate systemic perfusion and reducing myocardial oxygen demand. Its role is particularly notable when used before percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). The DANGER Shock trial demonstrated a 13% absolute reduction in 180-day mortality with Impella CP support compared to standard care (45.8% vs. 58.5%), although it was associated with higher complication rates, including bleeding, limb ischemia, and hemolysis [146]. A meta-analysis also supports early Impella insertion prior to PCI, showing a significant reduction in short- and mid-term mortality without increasing procedural risks [147]. Moreover, findings from the USpella Registry highlighted better survival to discharge and more complete revascularization when Impella was used pre-PCI [148]. These studies underscore the potential of Impella as a valuable addition to unloading strategies in AMICS, though patient selection remains crucial due to the associated risks [147,148].

Myocardial cooling: Therapeutic hypothermia in cardiogenic shock

Therapeutic hypothermia, or myocardial cooling, has emerged as a potential adjunctive therapy in managing cardiogenic shock. The COOL Shock I & II studies demonstrated that moderate hypothermia (target temperature 33°C) in patients with cardiogenic shock led to decreased heart rate and increased stroke volume, cardiac index, and cardiac power output, without severe adverse effects [149]. The CHILL-SHOCK trial further supported this approach by showing that temperature-controlled cooling was feasible and safe, improving some hemodynamic markers in AMI-related cardiogenic shock [150]. However, the SHOCK-COOL trial reported no significant improvement in cardiac power index or 30-day mortality in patients with cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction [151]. These variable outcomes suggest myocardial cooling is promising but requires further investigation in larger randomized controlled trials before routine clinical application.

Myoblast autologous grafting in ischemic cardiomyopathy

Autologous myoblast transplantation (AMP) has been investigated for ischemic cardiomyopathy to improve myocardial regeneration and microvascular function through paracrine effects and potential cardiomyocyte regeneration. Early studies suggested improvements in mitochondrial function and coronary flow reserve [152,153]. However, the MAGIC trial did not show significant improvement in left ventricular function or long-term survival compared with standard care and reported a higher incidence of ventricular arrhythmias [59]. Current evidence does not support clear functional or survival benefits, and safety risks require careful consideration before clinical use.

Digitalis and cardiotonic steroids

Digitalis, particularly digoxin, has been a key treatment for heart failure, enhancing cardiac contractility through Na+/K+-ATPase inhibition [154,155]. Although its use has declined due to newer therapies, recent studies suggest it may still benefit specific populations, such as those with atrial fibrillation (AF) who have MI and concomitant heart failure. In AF patients without heart failure, digoxin usage after MI increases the risk for mortality and should be used with caution [156–159]. Digotoxin, a cardiac glycoside similar in structure to digoxin, has shown some promise in mitigating adverse cardiac remodeling in rats with large MI and heart failure by reducing nuclear volume expansion and reducing collagen accumulation [160–162].

Novel delivery systems for cardiac therapies

Advancements in drug delivery systems (DDS) are crucial for improving therapeutic efficacy in cardiac treatments. Traditional methods often struggle with poor bioavailability and systemic side effects. Nanoparticle-based systems enhance drug solubility and stability, allowing for targeted delivery, such as doxorubicin-loaded nanoparticles that reduce cardiotoxicity while maintaining efficacy [163]. Microneedle arrays provide a minimally invasive option for sustained transdermal drug release, improving patient compliance [164]. Hydrogels can encapsulate drugs and respond to stimuli for localized delivery, while intramyocardial injections directly target myocardial tissue, enhancing drug concentrations post-myocardial infarction [165]. Catheter-based systems and extracellular vesicles also facilitate targeted delivery, promoting myocardial repair [166]. Despite challenges like rapid clearance and injection risks, ongoing research aims to optimize these innovative systems for effective cardiac care. Table 3 lists advantages and disadvantages to different delivery methods to the heart. Table 4 further summarizes these novel delivery systems.

|

Method |

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

|

Surgical |

|

|

|

Cell sheet, tissue strip or patch |

Allows precise material delivery by direct visualization of the target site; suitable for larger materials and can be integrated with cardiac surgery. |

Requires open-chest surgery; can require mechanical circulatory support when cardiac dejection is needed; fixation of the material precisely is difficult. |

|

Epicardial injection |

Direct visualization of the target site allows precise delivery; gradient administration can be achieved over the heart wall; can be combined with cardiac surgery. |

Requires open-chest surgery; intramyocardial injection may cause local tissue injury or arrhythmias, which are usually transient and managed clinically. |

|

Painting |

Effective gene transfer to thin walls (for example, atria), which can be targeted. |

Needs open-chest surgery; limited transmurally for thick walls. |

|

Catheter-based |

||

|

Antegrade intracoronary administration, with or without balloon occlusion |

Less invasive than surgical approaches; homogenous distribution; devices and techniques clinically used for coronary and valvular interventions can be adapted for gene delivery. |

Delivery depends on antegrade coronary perfusion for homogenous distribution, which might limit approaches such as retrograde perfusion. Complex preparation is required. |

|

Coronary artery intervention with drug-eluting balloon or stent |

Sophisticated techniques and devices, less invasive; supplies the vector to the coronary arteries in combination with the slow release of the agent. |

For the stenosed arteries, stents may be required to maintain patency. |

|

Retrograde coronary venous injection, including balloon occlusion |

Minimizes dependence on antegrade flow, circumvents perfusion pressure drop across the coronary arterial bed. |

Difficult to target the right ventricle because of challenges in selecting the right coronary veins; off-target transduction risk in other tissues. |

|

Endocardial injection |

Direct targeting of regions with arrhythmogenic substrate. |

Requires a mapping system for precise targeting; difficult to administer to thin walls. |

|

Pericardial delivery |

Transmural transmigration approach might be beneficial for conditions primarily affecting myocardial layers, such as for myocardial fibrosis or myocardial infarction. |

Transthoracic percutaneous catheterization can limit access to the pericardial space; patients with myocardial infarction or pericardial effusion could cause cardiac tamponade. |

|

Other |

|

|

|

Systemic administration |

Less invasive than either catheter-based or surgical approaches; universally applicable. |

Potential for off-target uptake in other organs and systems; limitations in achieving tissue specificity. |

|

Source: Sahoo S, et al. [166] |

||

|

Drug Delivery Methods |

||

|

Surgical Approach |

CATHETER BASED APPROACH |

OTHER APPROACHES (Post systemic Administration of Therapeutic Agent) |

|

1. Cell sheet / tissue strip / biomaterial patch |

5. Via Coronary Artery |

Ultrasound guided-microbubble destrutction at target site(heart) |

|

2. Epicardial injection |

6. Via Coronary Sinus |

|

|

3. Painting |

7. Transvalvular Endocardial Injection |

Magnetically-directed delivery of magnetically conjugated materials (Magnets/MRI) |

|

Source: Sahoo S, et al. [166] |

||

Nanotechnology in cardiac therapy

Nanotechnology enhances drug delivery and targeting in cardiac therapy, particularly after MI. Traditional treatments face challenges like poor solubility and off-target effects. Nanoparticles (NPs), such as enzyme-responsive types, improve bioavailability and reduce toxicity by delivering MMP inhibitors directly to infarcted tissue, enhancing therapeutic efficacy [167]. These NPs respond to the enzymatic environment, releasing drugs at injury sites and minimizing side effects [168]. Advantages include enhanced targeting of specific receptors, controlled drug release, and reduced systemic exposure [167,169–171]. However, challenges like rapid clearance and injection risks during acute MI remain [169]. Future research should focus on improving circulation times and exploring safer delivery methods, potentially integrating advanced imaging techniques for real-time monitoring of nanoparticle distribution and efficacy.

Current Clinical Trials and Future Directions in Immunotherapy

Immune cells play a critical role in modulating processes underlying cardiac remodeling post-MI. Two recent studies demonstrated that both dendritic cells (DC) and T cells contribute significantly to cardiac remodeling following MI and tissue repair [156,157]. Although neither altered the infarct size, both cell types modulated initial healing and subsequent remodeling processes. Both cell types were associated with decreased mature collagen fibers and impaired angiogenesis. Both studies reported increased matrix metalloproteinases, which may exacerbate adverse remodeling. Notably, in two of the four models with alteration of T cell responses, survival was reduced with higher incidence of cardiac rupture. A third model demonstrated marked increase in left ventricular dilation. CD11c+ cell ablation also may have influenced survival although it was not statistically significant at the P<0.05 level. Most mortality occurred within the first week, indicating that the initial healing response was compromised (summarized in Figure 2) [172–174].

Figure 2. Immune response modulation post MI. (Richard M Mortensen) [172,173].

Immunomodulatory interventions in myocardial infarction and heart failure

The immune system exerts a dual role in cardiac remodeling. The first, beneficial role involves restoration of tissue integrity following MI [174,175]. In contrast, the second, detrimental role arises when excessive inflammation leads to adverse cardiac remodeling progressing to heart failure [175,176].

Owing to this dual role, pharmacologic interventions aim to modulate immune activity—either by enhancing its beneficial effects or suppressing its detrimental effects depending on the clinical context [177]. Immunomodulators enhance the protective immune functions, while immunosuppressors mitigate excessive or maladaptive immune responses [176,177].

Therapeutic strategies to control post-MI inflammation include four main approaches [174,178]. Firstly, blockade of early inflammatory initiators, such as reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the complement system, targets key contributors to oxidative stress and tissue injury [174,177]. Secondly, inhibition of mast cell degranulation and leukocyte infiltration is employed, as these cells release mediators that aggravate myocardial damage and remodeling [177]. Thirdly, blockade of inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, is implemented to mitigate inflammatory response and prevent adverse cardiac remodeling [176]. Finally, inhibition of adaptive immune cells, particularly B-lymphocytes and T-lymphocytes, has been proposed to reduce prolonged immune activation and limit maladaptive repair processes. Collectively, these strategies emphasize the need for targeted modulation of the immune system to improve healing and outcomes following MI [178].

Stem cell transplantation has a promising role in cardiac remodeling following MI [179]. Adult stem cells, iPSCs, and ESCs are key cell types that have demonstrated the capacity to regenerate injured myocardial tissue in both preclinical models and clinical settings [179]. MSCs work as a double-edged sword [180]. They have a beneficial role, with unique immunomodulatory properties and the broad spectrum of paracrine factors they secrete, collectively contributing to myocardial repair and functional recovery following MI [179,180].

Despite this promise, significant challenges remain. The therapeutic potential of MSCs is frequently undermined by poor cell retention, limited engraftment efficiency, and a progressive decline in their regenerative effectiveness over time [175]. Therefore, ongoing research is increasingly directed toward optimizing delivery methods, enhancing MSC survival, and improving long-term functional integration to fully harness the regenerative potential of MSC-based therapies [180].

Challenges in Translating Novel Therapies from Laboratory to Clinical Practice

The implementation of novel therapies faces multiple challenges ranging from barriers associated with safety and efficacy to ethical, regulatory, and economic considerations [177]. Stem cell therapy, for example, is riddled with various challenges as the inconsistent results on efficacy and safety remain a problem yet to be solved. This barrier is linked to the limited survival, retention, and engraftment of the transplanted stem cells in the myocardial tissue [176]. The lack of sufficient data on stem cell fate after transplantation makes it difficult to accurately establish the standard dose-response relationship. Another barrier to clinical implementation is the higher risk of immunogenicity, arrhythmogenicity, and tumorigenicity in embryonic stem cells and pluripotent stem cells [178]. To achieve safe target delivery, gene editing systems such as the CRISPR-Cas9 system face the challenge of overcoming biological barriers such as cellular and endosomal uptake [179]. ARNI therapy has shown significant benefits in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) but may not be universally applicable to all AMI patients, especially in those without established heart failure [180]. Similarly, SGLT2 inhibitors use in non-diabetic AMI population requires further investigation [181]. The efficacy of antifibrotic agents is complicated by the need to balance fibrosis and normal healing processes. Scaffolds and hydrogels must not only support cell attachment and growth but also promote the appropriate signaling pathways for tissue regeneration. The incorporation of growth factors into hydrogels can enhance angiogenesis and cellular recruitment, but the controlled release of these factors remains a technical hurdle [182]. The integration of these therapies into existing treatment protocols can be challenging as the timing of initiation, patient-specific factors, potential drug interactions, dosing adjustments, and potential side effects can complicate the use of these therapies in acute care settings [183,184].

Synthesis of Key Findings

The management of cardiac remodeling following MI has evolved over the years. Novel therapies are gradually being evaluated alongside the standard treatment protocols. Many of these therapies, especially cell-based therapies, SGLT2 inhibitors, ARNI and, biomaterials, were found to significantly reduce LVEDV, LVESV, infarct size and serum BNP, thereby improving LV function compared to standard treatment. Cell-based therapy was found to be one of the most extensively studied, with inconsistent evidence of its benefits in clinical studies. This variability can be attributed to the varying routes of administration, cell type, dosing, mechanism of action and patient-specific factors. Biomaterials such as scaffolds and hydrogels can be employed as stand-alone therapies and can also serve as targeted delivery systems for growth factors and signaling factors generated by stem- and gene-based sources. The clinical trials reviewed in this study demonstrated positive effects on LV function with promising avenues for large-scale long- term studies on biomaterials. Studies on targeted delivery systems like exosomes and nanotechnology are primarily preclinical, with only a few clinical trials compared to other emerging therapies. While preclinical studies on these targeted delivery systems demonstrated the benefits of minimized off-target effects, visualization and tracking of these systems in vivo remains a significant barrier to clinical implementation. Though ACE inhibitors revolutionized the management of heart failure, the use of digoxin continues to be explored for management of heart failure in certain populations. Lifestyle modifications like exercise training and a plant- based diet were found to be beneficial for cardiac rehabilitation following MI.

Clinical Implications of Novel Therapeutic Strategies

While certain clinical studies have demonstrated the positive effects these therapies have on clinical outcomes, there are also contradictory studies. COMPARE-AMI patients who had EPC therapy were found to experience an improvement in LVEF at 12 months but on analysis of the long-term effect in the follow-up patients, no significant improvement was found [84]. This inconsistency is also observed in HSC therapy, where one study reported an improvement in LV function and perfusion while another concluded on its lack of efficacy in improving LV function [85,86]. A promising approach to address the challenges faced in stem cell therapy is the use of bioengineered materials. One study found the use of hydrogel to be safe in humans, with an improved exercise capacity at 6 months and a sustained benefits at one year [132]. Microencapsulated modified messenger RNA (M3RNA) and ELA gene therapy have the potential to positively influence clinical outcomes in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy [185,186]. A study by Yang et al. reported that sacubitril/valsartan produced outcomes similar to valsartan, in reducing LAV, LVDV, LVSV and inhibiting ventricular remodeling and heart failure in patients with AMI [187]. While ARNI consistently outperforms ACE inhibitors, the benefit over ARBs is less certain and appears to depend on patient population, clinical setting (chronic HFrEF vs acute MI), and study design. SGLT2 inhibitors have great potential for reducing the incidence of MI and preventing cardiac remodeling in patients with ischemic injury [188]. AMP transplantation has been shown to enhance myocardial energy metabolism and reduce oxygen demand with long-term survival rates in patients receiving AMP transplantation compared with patients receiving standard care [152,153].

Further Perspectives and Research Imperatives

Though the clinical studies on stem cell therapy are extensive, the clinical outcomes are inconsistent across different trials and follow-up durations. Therefore, large-scale studies with extended follow-up durations should be considered in future research on stem cell therapy. These trials should aim to evaluate the optimal timing, dosing, and route of administration for various stem cell types, to enable a robust assessment of their mechanisms of action, safety, efficacy, adverse effects, and dose-response relationships. Molecular imaging techniques can be integrated into studies investigating cell and gene-based therapy, biomaterials, growth factors, antifibrotic agents, and delivery systems [178,189]. Future studies should also focus on characterizing the host response to these novel therapies, especially in the setting of comorbidities and existing treatment protocols and guidelines.

Conclusion

The current standard of care for preventing cardiac remodeling in patients post-MI involves established treatment regimens which include ACE inhibitors, ARBs, beta-blockers, and aldosterone antagonists. However, emerging pharmacological therapies involving ARNIs and SGLT2 inhibitors, have demonstrated systemic and metabolic benefits along with anti- inflammatory properties. Other approaches, such as regenerative medicine, employ sophisticated bioengineering techniques including cardiac patches, hydrogels and systemic stem cells to address issues regarding immunogenicity and improving cell survival. Lastly, targeted molecular therapies aim to precisely modulate pro-fibrotic processes.

Author Contributions

Faizan Wadood Siddiqui: Conceptualization, Project administration, Supervision.

Faizan Wadood Siddiqui, Manahil Ali, Abieyuwa Tari-Ere Oshodin, Sheima Gaffar, Sherien Metry, Sawera Gul: Writing- Original draft preparation, Data curation, Validation, Writing- Reviewing and Editing.

Muhammad Ali Muzammil: Supervision.

Acknowledgments

None.

Conflicts of Interest/Disclosures

The authors certify that they have NO affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The authors report no external funding.

Ethical Statement

Institutional IRB approval was not obtained for this study as this is a review article.

Patient Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Guarantor of the Manuscript

All authors.

References

2. Zhao W, Zhao J, Rong J. Pharmacological Modulation of Cardiac Remodeling after Myocardial Infarction. Han X, editor. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2020;2020:1–11.

3. Leancă SA, Crișu D, Petriș AO, Afrăsânie I, Genes A, Costache AD, et al. Left Ventricular Remodeling after Myocardial Infarction: From Physiopathology to Treatment. Life [Internet]. 2022;12(8):1111.

4. Masci PG, Ganame J, Francone M, Desmet W, Lorenzoni V, Iacucci I, et al. Relationship between location and size of myocardial infarction and their reciprocal influences on post- infarction left ventricular remodelling. Eur Heart J. 2011;32(13):1640–8.

5. Velagaleti RS, Pencina MJ, Murabito JM, Wang TJ, Parikh NI, D’Agostino RB, et al. Long-Term Trends in the Incidence of Heart Failure After Myocardial Infarction. Circulation. 2008;118(20):2057–62.

6. Störk S, Hense HW, Zentgraf C, Uebelacker I, Jahns R, Ertl G, et al. Pharmacotherapy according to treatment guidelines is associated with lower mortality in a community-based sample of patients with chronic heart failure A prospective cohort study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2008;10(12):1236–45.

7. Lam CSP, Arnott C, Beale AL, Chandramouli C, Hilfiker-Kleiner D, Kaye DM, et al. Sex differences in heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2019;40(47):3859–68c.

8. Kannel WB, Hjortland M, Castelli WP. Role of diabetes in congestive heart failure: the Framingham study. Am J Cardiol [Internet]. 1974;34(1):29–34.

9. Frantz S, Hundertmark MJ, Schulz-Menger J, Bengel FM, Bauersachs J. Left ventricular remodelling post-myocardial infarction: pathophysiology, imaging, and novel therapies. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(27).

10. Curley D, Lavin Plaza B, Shah AM, Botnar RM. Molecular imaging of cardiac remodelling after myocardial infarction. Basic Res Cardiol. 2018;113(2).

11. Schirone L, Forte M, Palmerio S, Yee D, Nocella C, Angelini F, et al. A Review of the Molecular Mechanisms Underlying the Development and Progression of Cardiac Remodeling. Oxid Med Cell Longev [Internet]. 2017;2017:1–16.

12. Sciarretta S, Maejima Y, Zablocki D, Sadoshima J. The Role of Autophagy in the Heart. Annu Rev Physiol. 2018 Oct;80:1–26.

13. Whelan RS, Kaplinskiy V, Kitsis RN. Cell Death in the Pathogenesis of Heart Disease: Mechanisms and Significance. Annu Rev Physiol. 2010;72(1):19–44.

14. Kemp CD, Conte J V. The Pathophysiology of Heart Failure. Cardiovascular Pathology [Internet]. 2012;21(5):365–71.

15. Müller AL, Dhalla NS. Role of various proteases in cardiac remodeling and progression of heart failure. Heart Fail Rev. 2011;17(3):395–409.

16. Pamias-Lopez B, Ibrahim ME, Pitoulis FG. Cardiac mechanics and reverse remodelling under mechanical support from left ventricular assist devices. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2023;10.

17. Sun B, Liu Z. From support to recovery: the evolving role of LVAD in reversing heart failure. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2025;20(1).

18. Pandey AK, Bhatt DL, Cosentino F, Marx N, Rotstein O, Pitt B, et al. Non-steroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists in cardiorenal disease. Eur Heart J. 2022 Jun 17;43(31):2931–45.

19. Konstam MA, Patten RD, Thomas I, Ramahi T, Bresh K La, Goldman S, et al. Effects of losartan and captopril on left ventricular volumes in elderly patients with heart failure: Results of the ELITE ventricular function substudy. Am Heart J. 2000;139(6):1081–7.

20. Zhang N, Wang Y, Tse G, Korantzopoulos P, Letsas ΚP, Zhang Q, et al. Effect of sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors on cardiac remodelling: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2021;28(17):1961–73.

21. Dhingra NK, Mistry N, Puar P, Verma R, Anker S, Mazer CD, et al. SGLT2 inhibitors and cardiac remodelling: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized cardiac magnetic resonance imaging trials. ESC Heart Fail. 2021;8(6):4693–700.

22. Rodés‐Cabau J, Lindenfeld J, Abraham WT, Zile MR, Kar S, Bayés‐Genís A, et al. Interatrial shunt therapy in advanced heart failure: Outcomes from the open‐label cohort of the RELIEVE‐HF trial. Eur J Heart Fail. 2024;26(4):1078–89.

23. Grybauskiene R, Karciauskaite D, Brazdzionyte J, Janenaite J, Bertasiene Z, Grybauskas

24. P. Brain natriuretic peptide and other cardiac markers predicting left ventricular remodeling and function two years after myocardial infarction. Medicina (Kaunas) [Internet]. 2007;43(9):708–15.

25. Lamblin N, Bauters A, Fertin M, de Groote P, Pinet F, Bauters C. Circulating levels of hepatocyte growth factor and left ventricular remodelling after acute myocardial infarction (from the REVE-2 study). Eur J Heart Fail [Internet]. 2011;13(12):1314–22.

26. Ohtsuka T, Hamada M, Inoue K, Ohshima K, Suzuki J, Matsunaka T, et al. Relation of circulating interleukin-6 to left ventricular remodeling in patients with reperfused anterior myocardial infarction. Clin Cardiol. 2004;27(7):417–20.

27. Mao S, Liang Y, Chen P, Zhang Y, Yin X, Zhang M. In‐depth proteomics approach reveals novel biomarkers of cardiac remodelling after myocardial infarction: An exploratory analysis. J Cell Mol Med. 2020;24(17):10042–51.

28. Cohn JN, Tognoni G. A Randomized Trial of the Angiotensin-Receptor Blocker Valsartan in Chronic Heart Failure. New England Journal of Medicine [Internet]. 2001;345(23):1667–75.

29. Pitt B, Poole-Wilson PA, Segal R, Martinez FA, Dickstein K, Camm AJ, et al. Effect of losartan compared with captopril on mortality in patients with symptomatic heart failure: randomised trial—the Losartan Heart Failure Survival Study ELITE II. The Lancet. 2000;355(9215):1582–7.

30. Packer M, Coats AJS, Fowler MB, Katus HA, Krum H, Mohacsi P, et al. Effect of Carvedilol on Survival in Severe Chronic Heart Failure. New England Journal of Medicine [Internet]. 2001;344(22):1651–8.

31. Zannad F, McMurray JJ V, Krum H, van Veldhuisen DJ, Swedberg K, Shi H, et al. Eplerenone in Patients with Systolic Heart Failure and Mild Symptoms. New England Journal of Medicine [Internet]. 2011;364(1):11–21.

32. Khattar RS. Effects of ACE-inhibitors and beta-blockers on left ventricular remodeling in chronic heart failure. Minerva Cardioangiol [Internet]. 2003;51(2):143–54.

33. Wollert KC, Meyer GP, Lotz J, Ringes Lichtenberg S, Lippolt P, Breidenbach C, et al. Intracoronary autologous bone-marrow cell transfer after myocardial infarction: the BOOST randomised controlled clinical trial. The Lancet. 2004;364(9429):141–8.