Abstract

Blastomycosis, formerly known as Gilchrist disease, Chicago disease, North American blastomycosis, or Namekagos fever, is an uncommon but underappreciated fungal infection seen mostly in immunocompetent people, caused by the fungi Blastomyces. Blastomyces dermatitidis and Blastomyces gilchristii are the most common species responsible for most infections in the United States of America. Blastomycosis can cause a wide variety of diseases, the most common being pneumonia as the lungs are usually the main primary entrance source of infection after inhalation of Blastomyces spores. However, dissemination from the lungs to other organs such as skin, bones, genitourinary, and central nervous system can occur.

We describe a 52-year-old female who was admitted to the hospital for unresolved pneumonia after failure to respond to multiple outpatient antibiotic treatments for a presumed diagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia, presenting with right-sided chest pain, fever, cough and weight loss for three weeks duration. Her initial Chest-X ray and CT chest revealed right middle lobe infiltrate, while her laboratory studies were significant for elevated white blood cells (WBC). The patient underwent diagnostic bronchoscopy which showed erythema of the right middle lobe bronchus with purulent secretion. Furthermore, cytology examination of specimens from bronchoalveolar lavage and bronchial brush from right middle lobe with (PAP) satin on thin prep and H&E stain on the cell block revealed an abundance of broad-base budding yeast consistent with Blastomyces organism, which was confirmed by molecular testing with DNA probe assay. Her serum and urine Blastomyces antigens were positive, above the limit of quantification. The patient was started on antifungal therapy with Amphotericin-B intravenously. In the process, her fever resolved and her respiratory symptoms slowly improved. She was discharged home with oral itraconazole which was to be continued for 6-12 months as an outpatient.

Keywords

Blastomycosis, Gilchrist disease, Pneumonia, Blastomyces, Fungal infection, Bronchoscopy, Climate change

Abbreviations

CAP: Community Acquired Pneumonia; WBC: White Blood Cells; B. dermatitidis: Blastomyces dermatitidis; B. gilchristti: Blastomyces gilchristii; BAL: Bronchoalveolar Lavage; CNS: Central Nervous System; ARDS: Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome; AIDS: Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome; CT: Computed Tomography; PAP: Papanicolaou; H&E: Hematoxylin and Eosin; AG: Antigen; CSF: Cerebrospinal Fluid; DNA: Deoxyribonucleic Acid

Introduction

Blastomycosis is an endemic fungal infection in Midwestern, South-eastern, and South-central United States [1,2]. Due to recent climate changes, it was noted that there is an increasing incidence of fungal infections in endemic areas that have been extending to new geographic regions in the United States and worldwide [3,4]. The actual incidence of blastomycosis is not accurately documented due to low level of awareness of healthcare providers, difficulties in confirming the diagnosis and high incidences of asymptomatic and subclinical infection [5]. Markedly, blastomycosis can affect both healthy and immunocompromised patients, although it is more commonly observed among immunocompetent persons of all ages, races, and genders. Although the spectrum of blastomycosis illness is broad, the lung is the most common site of primary infection after inhalation of Blastomyces spores. Dissemination by hematogenous spread can occur in almost all organs, with the skin being the most common site of dissemination which occurs in up to 40-80% of the cases, followed by bones, genitourinary and central nervous system [6]. The majority of persons who get infected with Blastomyces are usually asymptomatic or may experience mild respiratory illness that resolves spontaneously. At the same time the clinical presentation of acute pulmonary blastomycosis may include chest pain, cough, fever, dyspnea [7]. Chronic blastomycosis pneumonia can mimic pulmonary tuberculosis or malignancy [8,9]. Diagnosis of blastomycosis is challenging and usually delayed for several weeks to several months because its clinical symptoms, radiological findings and serological testing are non-specific and can mimic other common diseases [10]. Confirmation of diagnosis of blastomycosis requires either positive culture or cytological examination of specimen taken from affected organ revealing the distinct broad base budding yeast followed by molecular DNA probe assay testing for identification [11]. In endemic areas, fungal pathogens should be suspected as a possible organism causing pneumonia in any patient with a presumed diagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia who has failed initial antibiotic therapy [12]. Importantly, undertaking a detailed history of the patient’s’ recent and past travel to fungal endemic area, hobbies and work environment with increased risk of exposure to Blastomyces as well as thorough skin examination should be obtained in all patients presented with pneumonia [13]. The choice of antifungal therapy and duration for the treatment of blastomycosis depends on severity, immune status of the patient, age, pregnancy and specific organ involvement [14]. Although blastomycosis is an uncommon disease, it can potentially be a serious illness if it is not treated early as pulmonary blastomycosis can progress to ARDS leading to high mortality rate [15].

Case Report

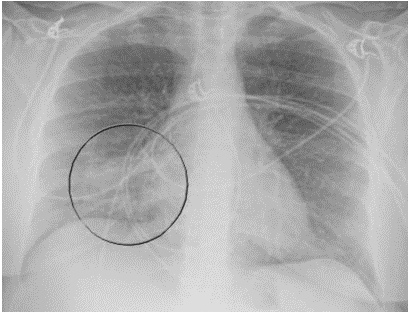

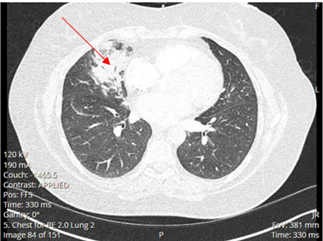

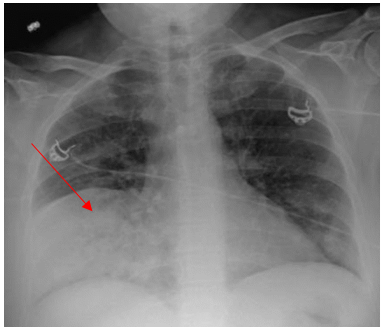

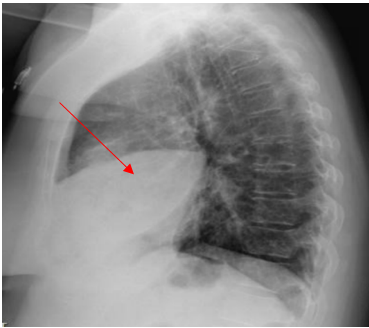

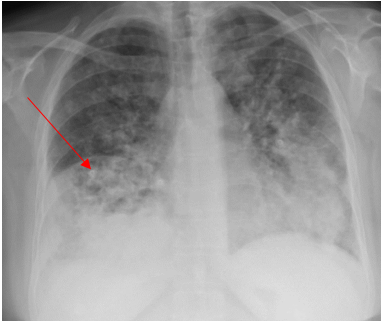

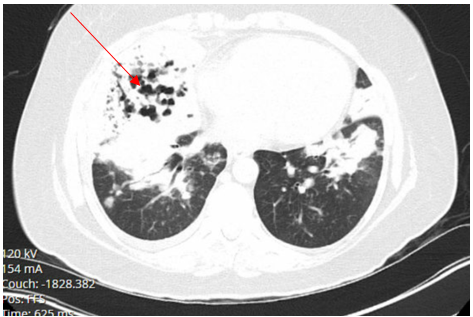

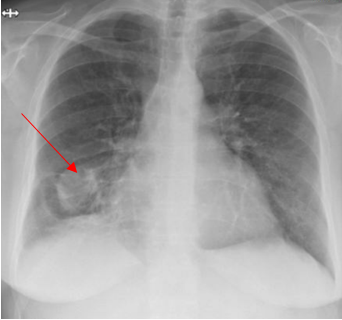

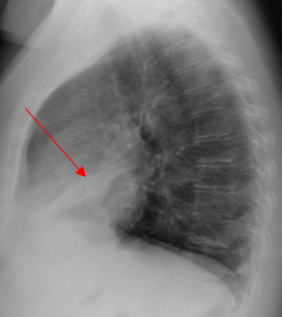

A 52-year-old Caucasian female, who is a resident of southwestern Ohio, presented to the emergency room with a chief complaint of a two-week history of right-sided chest pain, which had progressively worsened despite two courses of antibiotics and pain medications following her two recent visits to the emergency department. She also described subjective fever, shortness of breath, nonproductive cough and weight loss of 4 kg over the last two weeks. She was a smoker of ½ pack per day for 20 years and quit smoking 4 weeks ago. The patient’s past medical history includes anxiety, depression, gastroesophageal reflux disease, hypertension, mitral valve prolapse, and migraine headache. Her chest pain started in early September, and it was described as stabbing and pleuritic, which was also noted to be reproducible to palpation of the chest wall. She was seen first at the emergency department two weeks prior to the current presentation for evaluation of the right-sided chest pain. Still, at that time, there was no fever or cough, and her vitals were stable with Oxygen Saturation 94% on room air, although her laboratory testing was significant for leukocytosis with (WBC):16.6 K/UL with 68.5% neutrophils. Chest-X-ray demonstrated an infiltrate in the right lung base medially, while CT–chest angiography demonstrated no evidence of pulmonary embolism and right middle lobe consolidation consistent with pneumonia. There was no mediastinal or hilar lymphadenopathy, (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1. Portable Chest X-ray showing infiltrate in right lung base medially.

Figure 2. CT-chest angiography showing right middle lobe consolidation.

She was diagnosed with presumed community-acquired pneumonia, prescribed doxycycline 100 mg orally twice daily for ten days along with ibuprofen and discharged home to follow up with her primary care physician. However, the chest pain did not get better, and she presented again to the emergency room a week later, reporting unresolved chest pain in addition to new development of fatigue, shortness of breath, cough and intermittent fever with a maximum recorded temperature of 102°F (38.8°C) that has been measured at home. Upon her second presentation to the emergency department, her vital signs revealed a temperature of 98.9°F (37.2°C), blood pressure of 120/70 mmHg, Pulse of 99 per minute, and respiration of 16 per minute, and Oxygen saturation 99% on room air. Moreover, her repeat Chest -X-ray showed dense airspace opacity in the right middle lobe, while repeat CT Chest angiography did not reveal any evidence of pulmonary embolism. There was a consolidation in the right middle lobe and a smaller amount of infiltrate in the right lower lobe and right upper lobe but no pleural effusion. There was a calcified granuloma on the left lung and mediastinal lymphadenopathy with the largest mediastinal lymph node in the subcarinal region measuring 1.8 cm and 1.7 cm right hilar lymph node thought to be reactive to the pneumonic process. Laboratory testing was significant for leukocytosis with (WBC) 20.2 K/UL. She was discharged home again on oral Levofloxacin tablet 750 mg once daily for five days, oral prednisone tapering doses, along with ibuprofen and acetaminophen to follow up with her primary care physician. The patient came back again two days later to the emergency department with current presentation with persistent and unresolved right-sided chest pain located behind the shoulder blade and upper right chest and worsening respiratory symptoms, including dry cough, shortness of breath, subjective fever, chills and weight loss. The chest pain seems to get worse with deep inspiration while she lays flat and improves while sitting up. Her medications included Albuterol metered dose inhaler, atorvastatin, metoprolol, omeprazole, and levofloxacin. Physical examination was noteworthy for an ill-appearing person in mild respiratory distress with tachypnea and tachycardia. Her vitals included: temperature of 99°F (37.2°C), Respiration of 18 per minute, Pulse 99 beats per minute, blood pressure of 125/61 mmHg, Oxygen Saturation of 92%-94% on room air. The chest exam demonstrated diminished breath sounds at the right lung base with right lower chest scattered crackles and mild anterior and posterior right-sided chest wall tenderness. Also, there were no skin lesions observed.

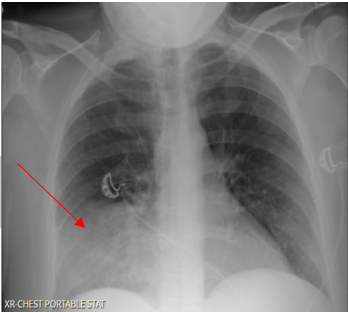

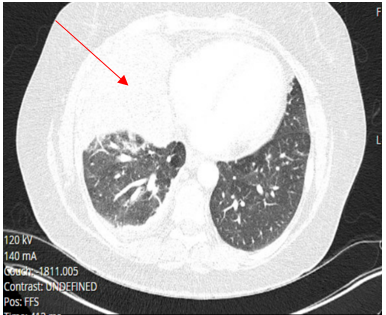

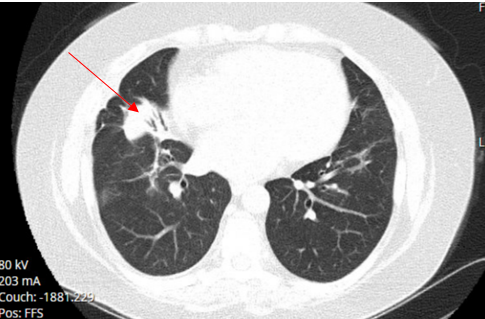

Laboratory testing was notable for elevated WBC, 19.5 (4.0-10.5 K/UL), neutrophils 78.3%, lymphocytes 7.7%, Monocytes 13.5%, eosinophils 0.2%, basophils 0.3%, Procalcitonin 1.46 ng/ml (reference range :< 0.25 ng/ml), SARS-COV 2 was negative. Blood culture, sputum culture, urine strep and legionella urine Antigens were negative, and the upper respiratory PCR panel was negative. MRSA PCR negative. Chest-X ray revealed a consolidation within the right lower lung field, while the CT Chest Angiography showed no evidence of acute pulmonary embolus. Furthermore, there was a progression of consolidative changes in the right middle lobe, traces of right pleural effusion, mild bilateral lower lobe atelectasis, and rounded opacity in the posterior left lower lobe measuring 10 mm. On the same note, there was rounded opacity in the right lower lobe measuring 13 mm, which was a new finding from the prior imaging study, and prominent mediastinal and hilar lymph nodes with the right paratracheal lymph node measuring 13 mm and right hilar lymph node measuring 19 mm (Figure 3 and 4).

Figure 3. Portable Chest X-ray on Hospital admission showing consolidation in the right lower lung field.

Figure 4. CT chest angiography on Hospital admission showing complete right middle lobe consolidation with trace right pleural effusion.

The patient was admitted to the hospital due to unresolved pneumonia and started on Oxygen 2L per nasal cannula, intravenous fluid with normal saline, intravenous Ceftriaxone and azithromycin along with intravenous methylprednisone, intravenous morphine for pain control, Albuterol inhalation therapy and enoxaparin subcutaneous injection for DVT prophylaxis. Intravenous Metronidazole was added to address possible anaerobic pathogens for suspected aspiration. However, follow-up swallowing evaluation by speech therapy was normal, with no evidence of aspiration. Within a few days of admission to the hospital, the patient developed shallow breathing, tachycardia with a pulse of 113 beats per minute, a temperature of 101.3oF (38.5oC), worsening right chest pain, cough, which became productive although there was no hemoptysis. As such, her oxygen requirement increased to 5 L/minute. Subsequent patient examination revealed decreased breath sound at the right base with scattered crackles and intermittent expiratory wheezes. A follow-up posteroanterior and Lateral views chest X-ray showed persistent extensive pulmonary consolidation in the right middle lobe (Figures 5 and 6).

Figure 5. Repeat Chest X-ray during Hospital stay showing right middle lobe consolidation with some subtle ground glass haziness to the reminder of the lung’s fields. (posteroanterior view).

Figure 6. Chest X-ray during Hospital stay showing right middle lobe consolidation. (lateral view).

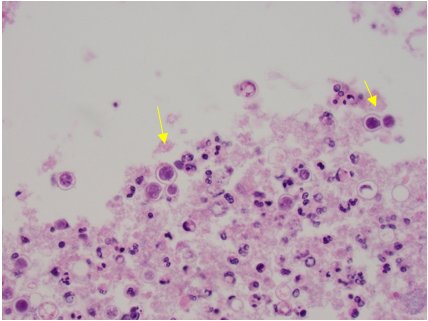

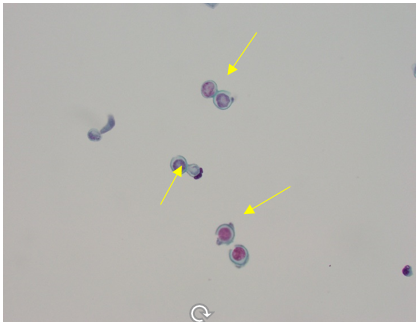

Within four days of admission to the hospital, consultations to pulmonary and infectious diseases teams were obtained. At this time, azithromycin was discontinued and given the patient's worsening clinical condition and failure to improve while on multiple antibiotics, she underwent a diagnostic bronchoscopy, which showed normal trachea and carina, erythema and purulent secretions filling the right middle lobe bronchus, and no endobronchial lesion. The right lower lobe and right upper lobe bronchus were normal. Microscopic and cytology brush and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) were performed at the right middle lobe. Acid-fast bacilli smear and culture from BAL were negative. Also, both aerobic and anaerobic cultures of BAL were negative. Cytology was negative for malignancy. In particular, cytological examination of BAL and brush from the right middle lobe demonstrated numerous fungal organisms with broad-based budding yeast consistent with Blastomyces (Figures 7 and 8). There was an abundance of fungal organisms seen initially on Papanicolaou (PAP) and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain preparation slides.

Figure 7. Cell block with H&E stain from cytology brush from right middle lobe showing numerous fungal organisms with broad-base budding consistent with Blastomyces (yellow arrows), associated with acute inflammation.

Figure 8. Thin prep slide from right middle lobe BAL with PAP stain showing abundance of fungal organisms with broad-base budding consistent with Blastomyces (yellow arrows).

The patient was diagnosed with pulmonary blastomycosis and started on Amphotericin -B 5 mg/kg/ IV every 24 hours, with close monitoring of renal function and electrolytes, including potassium, magnesium, and phosphate. All other Antibiotics and steroids were discontinued. Follow up Chest-X ray a week after bronchoscopy while the patient was in hospital showed extensive bilateral airspace infiltrates in both lungs most pronounced at the bases and CT chest showed progressive consolidations in the right lower lobe, lingula, left lower lobe, and right middle lobe with cavitary appearance in the right middle lobe suggesting necrotizing pneumonia with tiny left and small right pleural effusion (Figures 9 and 10).

Figure 9. Portable Chest X-ray a week after Bronchoscopy showing extensive bilateral airspace infiltrates in both lung fields, mostly in the mid to lower lung zones.

Figure 10. CT chest showing bilateral consolidation of the lung bases involving the lingula, left lower lobe, right lower lobe and right middle lobe with cavitary appearance of the right middle lobe consolidation.

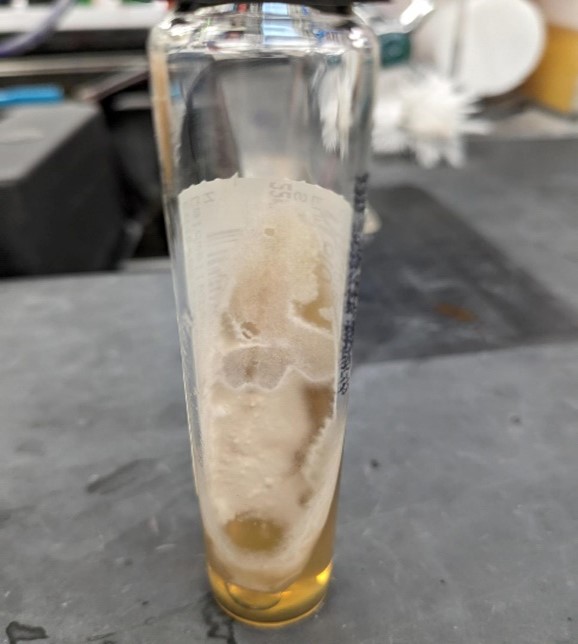

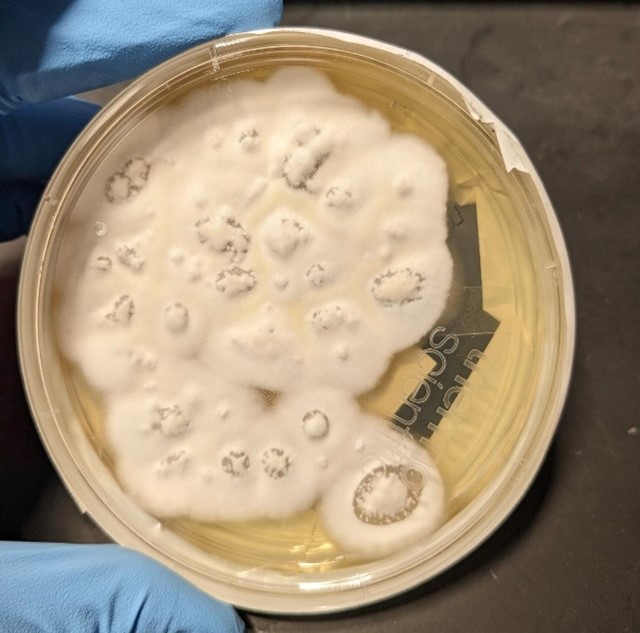

On further questioning the patient, she denied any recent travel history. More information from her household revealed she has an indoor dog and seven cats, but no birds and all her pets appeared healthy with no signs of sickness. Also, the patient provided information that there were no nearby constructions in her neighborhood, and she did not participate in any activities such as camping, fishing, boating, or hunting trips and there was no previous history of flooding in her home or living near a lake or river. A phone call to the veterinarian clinic in her residence indicated no recent cases of proven blastomycosis in dogs or cats seen in that clinic. Serum and urine Blastomyces quantitative (Q.N.) Antigen (A.G.) enzyme immunoassays (EIA) were positive above the limit of Quantification for the test (Reference lab range: None detected. Results above 14.7 ng/ml are reported as positive above the limit of Quantification, and results below 0.2 ng/ml are reported as positive below the Quantification). Urine and serum Histoplasma QN Ag EIA were positive, which was thought to be either a false be positive as a result of cross-reactivity with Blastomyces Antigen or a previously contained histoplasmosis infection. Nevertheless, serum Blastomyces Q.N. Antibodies, 1-3 B Glucagon, Aspergillus fumigatus, Aspergillus falvus, and Aspergillus nigar Antibodies were all negative. During the four weeks after bronchoscopy, the fungal culture of (BAL) grew molds on the Sabourand slant and agar (Figures 11 and 12). KOH, followed by Phenol Blue staining on the culture specimen could not distinguish a specific fungus organism.

Figure 11. Sabouraud dextrose slant culture of BAL showing growth of off-white mold.

Figure 12. Sabouraud dextrose agar (SAD) culture of BAL showing growth of off-white mold.

Fixed paraffin-embedded specimen block slides from bronchial washing and BAL were sent to a reference laboratory for Molecular fungal DNA probe assay testing by PCR, which detected Blastomyces dermatitidis or gilchristii as the sequence evaluated using this molecular testing does not permit more specific classification. The patient slowly improved clinically, and her fever resolved; she became afebrile a few days after starting Amphotericin B with and her oxygen supplement was weaned off to room air. Amphotericin B was continued for a total of 10 days while the patient was in the hospital. Thereafter, oral antifungal therapy was started using itraconazole 200 mg PO three times a day for two weeks, followed by 200 mg PO BID with a plan to treat the patient for 6-12 months. Her WBC was trending down, and she was discharged home to follow up with the infectious disease clinic for monitoring of serum itraconazole level, renal, and liver functions. Her chest X-ray 6 months after antifungal therapy showed a residual streak area of atelectasis in the right middle lobe, as shown in Figures 13 and 14).

Figure 13. Chest X-ray 6 months after antifungal therapy showing residual area of atelectasis in right middle lobe. (Posteroanterior view).

Figure 14. Chest X-ray 6 months after antifungal therapy showing residual area of atelectasis in right middle lobe. (Lateral view).

The patient's repeated CT chest without contrast after one year of antifungal therapy showed stable subtle tree-in-bud nodularity in bilateral upper lobes and small localized consolidation in the right middle lobe with a small air bronchogram which has a configuration suggesting round atelectasis and stable appearance of bilateral pulmonary nodularity (Figure 15). However, the infiltrate has improved significantly compared to previous images taken a year ago at the time of diagnosis.

Figure 15. CT chest one year after antifungal therapy showing rounded atelectasis in right middle lobe.

Therapeutic levels of Itraconazole and OH-itraconazole were monitored and maintained within the normal range during the entire period of therapy. On a similar note, follow-up serum Histoplasma Ag was negative after six months of itraconazole therapy, while serum Blastomyces Q.N. Antigen EIA level decreased subsequently over the next 12 months of antifungal therapy from the initial value of the above limit of Quantification to 6.5 ng/ml, 6.43 ng/ml, 0.76 ng/ml, 0.29 ng/ml. Finally, the urine Blastomyces AG went below the detection level after completing almost 14 months of successful treatment with Itraconazole. At this point, Itraconazole was discontinued, and the patient was made aware of the potential risk of reactivation, particularly in case of needing to start immunosuppressive medications.

Discussion

Blastomycosis, previously called Gilchrist disease, Chicago disease, northern American blastomycosis or Namekagos fever, is an uncommon fungal infection caused by the dimorphic fungi of the genus Blastomyces [16]. These organisms exist and grow as mold with hyphae that produce spores under specific temperatures and humidity in the environment where they reside primarily in acidic soil but as a yeast in mammals' tissue, including humans and animals, at body temperature (37oC).

Blastomycosis affects both humans and animals, including dogs and rarely cats, although dogs, in particular, remain the most common animal infected by Blastomyces. The incidence of blastomycosis in general is < 2 human cases per 100,000 per year. Its incidence is less than other common fungal infections such as Histoplasmosis and Coccidiomycosis; however, using chart coding to determine the incidence of blastomycosis is usually limited and inaccurate and may not reflect the actual incidence [17]. The epidemiology of blastomycosis needs to be better defined due to the fact that the organism is complex to isolate from the environment, and testing soil for the presence of Blastomyces is not only challenging but also not reliable [18]. Canine blastomycosis incidence, most likely in dogs, is ten times higher than in humans, especially in hunting dogs, due to their instinct activity such as soil digging [19]. Dogs get infected more than cats due to the fact that most owned cats are indoors. Infection of dogs with Blastomyces indicates the fungus is present in the environment where the dog has been around. People in the same area could be at risk for infection with Blastomyces due to exposure to the same source rather than transmission of Blastomyces infection from a dog to a person, which is very unlikely unless a person suffered a dog bite from an infected dog with blastomycosis [19].

The actual incidence of human blastomycosis is probably much higher than what has been reported, as incidence usually represents recognized cases where diagnosis was made primarily on hospitalized patients with the most severe cases. However, there are many cases of blastomycosis have mild illness which resolve spontaneously or cases with asymptomatic went undiagnosed [20]. According to the 2023 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report, blastomycosis is only mandatory reportable infection to the Department of Public Health in only six states, including Wisconsin, Louisiana, Minnesota, Colorado, Arkansas, and Michigan [21]. Histoplasmosis is also a reportable infection in these states. Blastomycosis is an endemic infection in southeastern, South-Central, and Midwestern of the United States, in particular the states bordering the Mississippi and Ohio rivers, and states bordering the Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence Seaway, as well as the Canadian provinces of Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, and Saskatchewan [22].

In the most endemic state, specifically Wisconsin, the incidence of infection with blastomycosis is higher than average and can go up to 40 human cases per 100,000 annually in some Wisconsin counties [23]. Other endemic states include Arkansas, Mississippi, Kentucky, Louisiana, Ohio, Michigan, Illinois, Tennessee, and Alabama [24]. Due to recent climate changes, including milder winters, warmer summers and fewer days of frost, rising temperatures and increased humidity, severe storms and windy days that can carry the fungi aerosolized conidia, as well as natural disasters such as flooding, tornado, hurricane [25], which all support the survival and infectivity of Blastomyces, as a result of such climate changes, it was noted an increase incidence of fungal infections in general not only in already listed endemic areas to those specific fungi but also spreading to new areas in the United States and globally [26,27].

There appears to be growing literature supporting that blastomycosis may be acquired at home as Blastomyces can grow in people's homes, mainly in the basements and attics of old houses, in particular houses where people store wood in their basements or if there is damage in the basement foundation with communication to the outside soil, moisture and animal drooping [28,29]. Previously, B. dermatitidis has been isolated from between the walls of abandoned warehouses and house yards, suggesting that place of residence may be a significant factor for acquiring blastomycosis in places where rivers or beavers run through the residential area and with wooded and agricultural surroundings or close to waste-collection site [30]. It was also noted that during the COVID-19 pandemic, the incidence of fungal infection, including Blastomyces, has increased [31-33]. Historically, it was believed that immunocompetent humans and mammals are protected against fungal infection from the environment due to their higher body temperature than most fungi can tolerate. However, global warming has allowed fungi in the environment to develop tolerance to higher environmental temperatures, leading humans and animals to become more susceptible to fungal infection [34]. The endemic region of Blastomyces has been extended recently to include more states that previously were too cold for the mold to grow. Blastomycosis cases have been reported in most states that are not considered endemic without travelling history to endemic areas, as well sporadic human cases of blastomycosis have been reported in Africa, Hawaii, Israel, Asia, India, the Middle East, Mexico, South America and other parts of the world [35], suggesting the geographic range of Blastomyces infection is broader than what is reported [36]. However, due to difficulties in confirming the diagnosis, the actual geographic distribution of blastomycosis outside the United States and Canada still needs to be determined [37].

Storage of wood in the basement for use with a burning stove has been associated with an increased risk of exposure to Blastomyces [38]. Although Blastomyces infection affects mainly immunocompetent healthy people, immunocompromised patients such as single organ Transplant recipients, Patients with AIDS and positive HIV, patients using prolonged courses of steroids and the use of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha inhibitors and other immunomodulators drugs which used commonly in collagen vascular disease patients, hematogenous malignancies and those with impaired cell-mediated Immunity are all considered independent risk factor for acquiring and developing sever disseminated blastomycosis [39,40]. Blastomycosis is less common in general than histoplasmosis and coccidiomycosis in patients with AIDS and solid organ recipients. Although blastomycosis is uncommon in patients with AIDS, the majority of AIDS patients diagnosed with blastomycosis have CD4-T lymphocyte count < 200 cells/mm3 [41].

Many cases of blastomycosis are acquired sporadically from an environmental source, which is unidentified most of the time, but outbreaks in which several people have been infected are well documented. Blastomycosis outbreak has been reported after major interstate highway constructions [42]. Outbreaks have also been reported in several states, such as Wisconsin, Indiana, Michigan, North Carolina, Illinois, Minnesota, Tennessee, and Virginia [43]. Although blastomycosis has been reported in all ages, races, and genders, it is more commonly diagnosed in middle age males. Sex, age, and race do not directly affect susceptibility to blastomycosis but rather represent variables that influence the likelihood of exposure to Blastomyces in the environment and the differences between men and women in participation in such outdoor activities and occupations. Blastomycosis is less commonly seen in children [44].

Several local host factors are triggered after inhalation of the conidia, including alveolar macrophages, monocytes, neutrophils, and lymphocytes. Alveolar macrophages phagocyte and kill the conidia, inhibiting its transformation to yeast form, which is usually resistant to killing by macrophages due to its thick wall, leading to an inflammatory response consisting of clusters of neutrophils with epithelioid and giant cells causing granuloma formation with or without necrosis which can mimic what usually seen in other fungus and non-fungus infection such as histoplasmosis, coccidiomycosis, tuberculosis or autoimmune disease such as sarcoidosis [45]. In the early phase of infection with Blastomyces and immunocompromised patients, there is minimal or no granuloma formation. Control of infection with Blastomyces primarily depends on cellular immunity, including T lymphocytes that have been sensitized to Blastomyces antigen [46]. Humoral immunity develops but does not play a significant role in host defense against blastomycosis and is not as crucial as cellular immunity. Impaired cellular Immunity and lymphopenia are considered a risk factor for developing severe disseminated blastomycosis disease and increased mortality [47].

The lungs are the most common site of primary infection with Blastomyces, which starts by inhalation of Blastomyces conidia that are aerosolized to the air when contaminated soil is disturbed. Humidity, as well as precipitation, encourages the release of Blastomyces spores into the environment [48]. From the primary pulmonary infection, Blastomyces can disseminate mainly by hematogenous spread and less commonly by lymphangitic spread or both to almost all organs if the host response in the lungs fails to contain the infection [49]. In the lung, conidia transform into thick wall budding yeast, which can cause pulmonary disease and from the lung can spread in a lymphohematogenous way to almost any organ, with the skin being the most common site of dissemination [50]. Risk factors for developing severe blastomycosis include immunosuppression, diabetes mellites, obesity, and pregnancy due to reduced cellular immunity and perinatal transmission has been reported [51].

Pulmonary blastomycosis infection has a broad range of clinical presentations, which can be indistinguishable from viral or bacterial pneumonia, leading to delays in diagnosis, which results in increased morbidity and mortality [52]. Due to its clinical variability, blastomycosis has been called the great pretender. The vast majority of immunocompetent persons with Blastomyces infection are asymptomatic or have self-limited mild respiratory illness such as flu-like illness often goes unrecognized and resolves spontaneously. Acute Blastomyces pneumonia, which most of the time mimics the presentation of community-acquired pneumonia, can progress into acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in 10% of the cases, more frequently seen in immunocompromised patients and associated with a very high mortality rate of 50-90% [53]. Untreated patients with acute pulmonary blastomycosis can develop necrotizing bronchopneumonia or chronic pneumonia mimicking pulmonary tuberculosis with weight loss, chronic cough, anorexia and night sweats. The onset of symptoms in acute blastomycosis pneumonia can start several weeks to several months following exposure and inhalation of Blastomyces spores, which can include fever, cough dry or productive, muscle aches, joint pain, chills, dyspnea, fatigue, night sweats, chest pain, hemoptysis, and weight loss if the disease becomes chronic and undiagnosed [54]. However, some patients can present with pulmonary blastomycosis several years after exposure, after visiting and leaving the endemic area, as the initial pulmonary infection is contained in the lung due to the defense mechanism of cellular immunity but is not eradicated completely. If the person's immune system function is reduced secondary to many factors, then a reactivation can occur. Many patients with acute pulmonary blastomycosis are diagnosed initially as bacterial community-acquired pneumonia as symptoms of pulmonary blastomycosis can be indistinguishable from other bacterial pneumonia. Radiographic findings of pulmonary blastomycosis are nonspecific, ranging from lobar consolidation with air bronchogram, patch alveolar or reticular infiltrate, mass-like lesion mimicking malignancy of the lung, nodular infiltrate of different sizes. However, cavitary pulmonary infiltrate mimicking pulmonary tuberculosis is uncommon but can be seen as well as bilateral interstitial infiltrate and miliary pattern. Large pleural effusion is uncommon, but a small one has been reported. Hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathy, which are commonly seen in histoplasmosis, are uncommon with blastomycosis but can be seen in 10-20% of patients with blastomycosis [55].

Increased mortality rates in patients with pulmonary blastomycosis have been associated with advanced age, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus, obesity, underlying malignancy, most commonly hematological malignancies, and solid organ recipients [56].

Extrapulmonary dissemination of blastomycosis, which occurs mainly by hematogenous spread from the lung seen more frequently in immunocompromised patients in 20-50% of the cases but has been reported in immunocompetent ones and most patients with extrapulmonary dissemination disease has concomitant pulmonary blastomycosis with variable pulmonary symptoms [57]. Skin, by far, is the most common extrapulmonary site of dissemination in blastomycosis, which occurs in 40-80% of patients with disseminated disease [58]. Skin lesions from blastomycosis may appear after primary pulmonary blastomycosis has cleared spontaneously or if the primary infection was an asymptomatic, which makes the diagnosis more difficult without associated pulmonary disease [59]. In rare cases, primary cutaneous blastomycosis can occur as a direct infection of the skin during mishandling specimens of Blastomyces culture media in laboratory workers or during landscape work contamination with infected soil materials [60].

Skin lesions from blastomycosis can present as single or multiple lesions appearing on the face, neck, and extremities but can be seen anywhere in the body. A wide range of appearance such as red papule, purple nodule, papulopustular lesion, verrucose nodules with irregular borders and central ulceration, violaceous ulcerated nodule with granulomatous formation and micro abscesses while the classic skin lesion of blastomycosis is a verrucous crusted cutaneous lesion violet to grey in color with central ulceration. Skin manifestation of blastomycosis can mimic other skin disease diseases such as squamous cell or basel cell carcinoma of the skin, giant keratoacanthomas, pyoderma gangrenosum, granuloma inguinal, lupus vulgaris, lymphoma, syphilis or tuberculosis of the skin [61,62]. Skin lesion presentation of blastomycosis is the same whether it is from disseminated disease or as primary cutaneous blastomycosis. The bone is the second most common site for dissemination, following the skin, occurring in 5-25% of patients with disseminated disease, mostly involving long bones, vertebrae, skull and ribs, causing osteomyelitis, destructive bone lesions, abscess formation and paraspinal abscess [63]. Dissemination to CNS can occur in 5-10% of immunocompetent patients but is more commonly seen in immunocompromised patients presenting as headache, confusion or focal neurological deficit due to mass lesion in the brain, brain abscess, epidural abscess, or chronic meningitis. Likewise, dissemination to genitourinary organs occurs in 10% of cases, causing prostatitis, epididymitis, orchitis, salpingitis, tubo-ovarian abscess, and endometritis. On the contrary, sexually transmitted blastomycosis is very rare but has been reported. Other organ involvement in blastomycosis includes osteoarticular joints mimicking septic arthritis, spleen, adrenal gland, esophagus, liver, pancreas, breast, thyroid, eye involvement presenting as uveitis or iritis and endophthalmitis, larynx, kidneys, oral mucosa, retropharyngeal abscess, lymph nodes, and trachea [64,65].

Clinical diagnosis of blastomycosis is challenging [66]. Physicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for endemic fungal illness by increasing vigilance regarding fungal pneumonia as a possible cause of pneumonia, more importantly in endemic areas, with particular focus on patients who failed to improve after a course of antibacterial antibiotics or patients presenting with pneumonia and skin lesions. A detailed history of risk factors for exposure to Blastomyces, including hobbies, activities, current and past residence locations, recent home remodeling, daily exposure to road construction dust, use of the wood burning stove, use of community composite pile or travel in the previous few years to known endemic areas for Blastomyces should be obtained as well as thorough physical exam including any associated skin lesion.

Laboratory diagnosis of blastomycosis is confirmed by either positive culture or by direct visualization of yeast form in cytopathology specimen or both, followed by molecular testing for identification of Blastomyces using fungal DNA probe assay by PCR [67]. Growth of mold form of Blastomyces in culture media will demonstrate septate hyphae with incubation temperature at 25-27oC as white to off-white colonies. However, yeast form grows as buttery, soft tan colonies at 37oC. Blastomyces usually grow slowly in culture media and can take up to several weeks to be visualized but can grow as early as 5-14 days. While the yeast form of Blastomyces is distinct in morphology, the hyphae form morphology is not. Special media are required for the growth of Blastomyces, such as Sabouraud dextrose, potato dextrose agar and brain heart media. Handling Blastomyces culture media poses a severe biohazard to laboratory personnel, mandating extreme caution and adequate protection. DNA probe assay testing can be used on fresh fluid specimens such as BAL, CSF, and sputum, as well as paraffin-treated tissue or fluid samples [68].

B. dermititidis and B. gilchristii have very similar DNA sequences that can make it difficult for molecular DNA probe testing to differentiate between them. Sputum, tracheal aspirate if patient intubated, and gastric aspirate specimens have been used for direct microscopic visualization using 10% KOH (potassium hydroxide) treated preparation, which serves as an enzymatic agent that breaks down debris in a specimen, such as epithelial cells and WBCs to view the yeast. However, its sensitivity is low [69]. Another alternative confirmative testing for blastomycosis is the identification of the Blastomyces yeast phase organism by cytology or histopathology material using Papanicolaou (PAP), periodic acid-Schiff (PAS), hematoxylin and eosin stain or Grocott methenamine silver (GMS) stain demonstrating a distinct Blastomyces organism seen as spherical broad-base budding yeast with double-contour thick cell wall 8-15 micron in size under microscope examination supported by serological testing such as serum or urine using Blastomyces antigen detection. Cytology, which has a sensitivity of 38%-97% and specificity of 100%, and histopathology, which has a sensitivity of 81% and specificity of 100% in the identification of Blastomyces, can be rapid methods in establishing the diagnosis of blastomycosis while waiting for culture results [69]. The yield of cytology depends on the quality of the specimen, stain used and expertise of the cytopathologist. It is worth understanding that a negative cytology result does not rule out blastomycosis. Necrotizing or non-necrotizing granuloma formation seen in blastomycosis tissue biopsy specimens is a nonspecific finding, as it can be seen in other fungus and non-fungus infections as well as autoimmune diseases. Contamination or colonization of Blastomyces does not occur in airways or other parts of the human body and when Blastomyces are seen in specimens obtained from people or animals, it indicates an actual infection. Bronchoscopy with BAL, washing and brush has a high diagnostic yield but is considered an invasive procedure [70].

The serological testing available for the detection of Blastomyces antigen includes serum and urine enzyme immunoassay (EIA) Blastomyces Antigen, which detects galactomannan in the cell wall of Blastomyces that is also part of the cell wall structure of another fungus such as Histoplasma, Coccidiosis, Paracoccidioides brasiliensis and Talaromyces marneffei with sensitivity range from 76%-93% for the urine Blastomyces antigen while sensitivity for the serum Blastomyces antigen is 56-82% [71]. Detection of Blastomyces antigen in urine or serum provides a rapid supportive method for a probable diagnosis of blastomycosis but with low specificity due to a high degree of cross-reactivity with another mycosis [72]. A negative serum or urine Blastomyces antigen does not exclude the probability of blastomycosis. Antigen titer measurement can be used in monitoring treatment to ensure response to therapy as a decrease in urine and serum Blastomyces antigen correlates with response to therapy [73]. Initial post-treatment increase in serum or urine Blastomyces antigen may reflect fungal cell wall breakdown due to undergoing degradation of Blastomyces. During the completion of treatment, serum and urine Blastomyces antigen usually become negative [74].

Serum Blastomyces antibody measurement, when positive, indicates the presence of IgG and or IGM against Blastomyces, which are detected by immunodiffusion assays (IDF) and have a low sensitivity of 28%-65%. In contrast, its specificity is 100%. Complement fixation assay sensitivity for serum Blastomyces antibody is 9%-57%, while its specificity ranges from 30%-100%. Serum Blastomyces antibody testing is not considered very useful for the diagnosis of acute blastomycosis as it takes time to develop and produce antibodies against Blastomyces after primary infection and may not develop in the immunocompromised patient [75].

The treatment choice of blastomycosis and duration of therapy depend on several factors, including severity of disease, organ involvement, response to therapy and immune status of the patient [76]. The current recommendation is to treat all patients with confirmed blastomycosis regardless of immune status, severity of present illness or time of diagnosis, even in untreated patients with spontaneous resolution of disease to prevent reoccurrence by reactivation or extrapulmonary dissemination. Previously, selected non-immunocompromised patients who are asymptomatic or with mild non-disseminated pulmonary blastomycosis whose symptoms resolved by the time the diagnosis is made, which may take several weeks to several months, are offered close observation for several years without treatment. Evaluation of hematology, hepatic and renal function is needed before initiation of therapy for blastomycosis as well as during therapy [77]. All pregnant patients and neonates with confirmed blastomycosis should be treated with Amphotericin B during the entire therapy duration due to the teratogenicity of azole. Monitoring kidney function is essential during amphotericin B therapy to avoid renal toxicity [78].

Mild to moderate blastomycosis without CNS involvement in adult male and non-pregnant women can be treated with oral azole for 3-6 months, depending on clinical and radiographic response. Itraconazole is the drug of choice in the azole group for blastomycosis. Fluconazole at a higher dose and voriconazole may be used as an alternative to itraconazole in patients who cannot tolerate itraconazole in step-down therapy in patients with (CNS) blastomycosis due to excellent penetration into CNS. Severe pulmonary blastomycosis, as well as disseminated disease and CNS blastomycosis, should be treated initially with Amphotericin B for 1-4 weeks or until clinical improvement, then, treatment can be transitioned to oral itraconazole for a total of 6-12 months. In most cases of blastomycosis, treatment with antifungal is usually started before confirmation of blastomycosis when clinical presentation suggests fungal infection. Obtaining a CT or MRI of the brain needs to be considered in immunosuppressed patients with pulmonary blastomycosis or in patients with disseminated blastomycosis to rule out the presence of CNS involvement, which can be insidious and asymptomatic [79].

Steroids have been used in some patients with ARDS due to severe progressive pulmonary blastomycosis as an adjuvant therapy to reduce the inflammatory response in the lungs and improve gas exchange. However, there is no randomized controlled trials to support the use of steroids in patients with ARDS associated pulmonary blastomycosis as there is no evidence to show improved outcome with their use [80]. Due to variable absorption of itraconazole formulation and wide inter-personal variability in drug metabolism and serum concentration, therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) of itraconazole is recommended to ensure adequate absorption and serum drug level for efficacy, patient compliance and to avoid dose-related side effects and toxicity such as hepatic toxicity. TDM of itraconazole should be obtained after two weeks of starting therapy and periodic monitoring of quantitative urine or serum Blastomyces antigen level during treatment period is a common practice. Because azoles can lengthen QT interval and increase the risk of statin-induced rhabdomyolysis, reviewing patients' medications is essential before starting therapy. Besides, Itraconazole has a negative inotropic effect, and patients with Congestive heart failure (CHF) who started on Azole should be monitored carefully for symptoms of (CHF) exacerbation [81].

Immunocompromised patients and patients with extrapulmonary disseminated disease as well as CNS involvement should always be treated initially with amphotericin B for a few weeks or until clinical improvement is achieved, then can be transitioned to Azole, most commonly used itraconazole, for a total of 12 months. In some immunocompromised patients with persistent immunosuppression such as AIDS, solid organ transplant recipients on immunosuppressive therapy with blastomycosis and in patients with relapsed blastomycosis after initial successful therapy with recommended duration and adequate serum level of itraconazole, some experts advocate life-long therapy with itraconazole may be needed to reduce relapse or recurrence [82]. Surgical intervention for drainage may be required in selected patients with blastomycosis abscess formation in organs such as the lung, brain, epidural, bone, and skin as part of management in addition to antifungal therapy. Cell-mediated Immunity after infection with Blastomyces may last only for a few years in some patients, and reinfection or relapse after treatment can occur. Relapse of blastomycosis in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients despite appropriate therapy, which is treated according to recommendation, has been documented although it is uncommon with an incidence rate of < 5%. At the same time, reinfection with Blastomyces can occur with the same species previously infected the patient or with a different genotype of the same species and re-infection with a different Blastomyces species and subspecies can occur more likely in the endemic areas due to short-lived Immunity developed toward Blastomyces infection after treatment. The fact that there are several species and subspecies of Blastomyces with distinct DNA sequence may explain why lifetime immunity does not necessarily develop in all persons after infection with Blastomyces. Reactivation of previously untreated or undetected but contained infection, "latent infection", which can occur years after initial infection, is uncommon but has been reported [83].

Currently, there is no specific formal recommendation or guidance for preventive measures to be used against Blastomyces exposure [84]. Also, there is no supporting data that modification of individual behaviors or activity would change the incidence of Blastomyces. Nevertheless, there is no evidence that wearing a face mask during an outdoor activity or working will reduce exposure to Blastomyces infection. However, in situations where the risk of exposure to Blastomyces is very high such as in endemic areas or at work sites and in laboratory workers handling fungal culture media, wearing respiratory protective equipment is recommended by the Environment Bureau of Environmental and Occupational Health department such as N95 for high risk works in all of the many setting where exposure to Blastomyces spores could occur in endemic area are suggested at this time [85]. Presently, no vaccine is available yet to be offered to individuals at high risk in endemic areas to prevent blastomycosis.

Conclusion

Physicians should maintain a high level of suspicion for considering blastomycosis, particularly among patients who live or have lived in Blastomyces endemic area who are not responding to the initial antibiotic therapy for CAP with unidentified pathogen causing their pneumonia , or in patients with CAP associated with skin lesion or with extrapulmonary involvement, such as bone, genitourinary, CNS, and in patients with risk factors for acquiring Blastomyces such as occupation and outdoor activity commonly associated with Blastomyces exposure [86]. There is a need to increase awareness among physicians concerning Blastomyces’ geographic distribution in the U.S as many are not familiar with blastomycosis [86]. Utilizing multiple diagnostic tests are recommended when a patient is suspected of having blastomycosis. Most patients with confirmed blastomycosis were diagnosed using invasive procedure such as Bronchoscopy, CT guided biopsy or needle aspiration. Physicians and Veterinarian are encouraged to notify the local health department whenever cases of blastomycosis are diagnosed and confirmed to investigate possible common source of exposure and prevent further exposure to the people in their area. Considering blastomycosis as a possible cause of CAP in the appropriate setting during its early presentation will avoid delays in diagnosis, improve patients’ outcomes and contributes to decrease in morbidity and mortality rates [87].

Acknowledgments

None.

Conflicts of Interest

No conflicts of interest.

Funding

None.

References

2. Kunin JR, Flors L, Hamid A, Fuss C, Sauer D, Walker CM. Thoracic Endemic Fungi in the United States: Importance of Patient Location. Radiographics. 2021 Mar-Apr;41(2):380-98.

3. Benedict K, Roy M, Chiller T, Davis JP. Epidemiologic and ecologic features of blastomycosis: a review. Current Fungal Infection Reports. 2012 Dec;6:327-35.

4. Nnadi NE, Carter DA. Climate change and the emergence of fungal pathogens. PLoS Pathog. 2021 Apr 29;17(4):e1009503.

5. Furcolow ML, Busey JF, Menges RW, Chick EW. Prevalence and incidence studies of human and canine blastomycosis. II. Yearly incidence studies in three selected states, 1960-1967. Am J Epidemiol. 1970 Aug;92(2):121-31.

6. Bennie Ho K, Ng M, Tallon K. A case of disseminated blastomycosis with pulmonary, genitourinary, and osteoarticular involvement in southern Saskatchewan. J Assoc Med Microbiol Infect Dis Can. 2020 Mar 4;5(1):39-43.

7. Martynowicz MA, Prakash UB. Pulmonary blastomycosis: an appraisal of diagnostic techniques. Chest. 2002 Mar;121(3):768-73.

8. Joshi DR, Nambi S, Santosham R, Santosham R. Pulmonary blastomycosis masquerading as malignancy in india; case from a tertiary hospital in south india. International Journal of Travel Medicine and Global Health. 2022 Sep 1;10(3):134-6.

9. Bradsher RW Jr. The endemic mimic: blastomycosis an illness often misdiagnosed. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2014;125:188-202; discussion 202-3.

10. Castillo CG, Kauffman CA, Miceli MH. Blastomycosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2016 Mar;30(1):247-64.

11. Hage CA, Carmona EM, Epelbaum O, Evans SE, Gabe LM, Haydour Q, et al. Microbiological Laboratory Testing in the Diagnosis of Fungal Infections in Pulmonary and Critical Care Practice. An Official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019 Sep 1;200(5):535-50.

12. Britto J. Non-resolving Community Acquired Pneumonia (CAP) due to Blastomyces dermatitidis (Pulmonary Blastomycosis): Case Report and Review of Literature. The University of Louisville Journal of Respiratory Infections. 2018;2(1):9.

13. Choptiany M, Wiebe L, Limerick B, Sarsfield P, Cheang M, Light B, et al. Risk factors for acquisition of endemic blastomycosis. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2009 Winter;20(4):117-21.

14. McBride JA, Gauthier GM, Klein BS. Clinical Manifestations and Treatment of Blastomycosis. Clin Chest Med. 2017 Sep;38(3):435-49.

15. Lemos LB, Baliga M, Guo M. Acute respiratory distress syndrome and blastomycosis: presentation of nine cases and review of the literature. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2001 Feb;5(1):1-9.

16. Gilcrist Thomas Caspar. Protozoan Dermatitis. J Cutan Gen Dis. 1894; 12:496-9.

17. Seitz AE, Younes N, Steiner CA, Prevots DR. Incidence and trends of blastomycosis-associated hospitalizations in the United States. PLoS One. 2014 Aug 15;9(8):e105466.

18. Klein BS, Vergeront JM, Weeks RJ, Kumar UN, Mathai G, Varkey B, et al. Isolation of Blastomyces dermatitidis in soil associated with a large outbreak of blastomycosis in Wisconsin. N Engl J Med. 1986 Feb 27;314(9):529-34.

19. Baumgardner DJ, Burdick JS. An outbreak of human and canine blastomycosis. Rev Infect Dis. 1991 Sep-Oct;13(5):898-905.

20. Litvinov IV, St-Germain G, Pelletier R, Paradis M, Sheppard DC. Endemic human blastomycosis in Quebec, Canada, 1988-2011. Epidemiol Infect. 2013 Jun;141(6):1143-7.

21. Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. Reportable Fungal diseases by State. Sept 19, 2023. cdc.gov/fungal/fungal-diseases-reporting-table.html

22. Tosh FE, Hammerman KJ, Weeks RJ, Sarosi GA. A common source epidemic of North American blastomycosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1974 May;109(5):525-9.

23. Klein BS, Vergeront JM, DiSalvo AF, Kaufman L, Davis JP. Two outbreaks of blastomycosis along rivers in Wisconsin. Isolation of Blastomyces dermatitidis from riverbank soil and evidence of its transmission along waterways. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987 Dec;136(6):1333-8.

24. Goico A, Henao J, Tejada K. Disseminated blastomycosis in a 36-year-old immunocompetent male from Chicago, IL. Oxf Med Case Reports. 2018 Sep 24;2018(10):omy071.

25. Szeder V, Ortega-Gutierrez S, Frank M, Jaradeh SS. CNS blastomycosis in a young man working in fields after Hurricane Katrina. Neurology. 2007 May 15;68(20):1746-7.

26. Ross JJ, Koo S, Woolley AE, Zuckerman RA. Blastomycosis in New England: 5 Cases and a Review. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2023 Jan 20;10(1):ofad029.

27. Benedict K, Gibbons-Burgener S, Kocharian A, Ireland M, Rothfeldt L, Christophe N, et al. Blastomycosis Surveillance in 5 States, United States, 1987-2018. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021 Apr;27(4):999-1006.

28. Baumgardner DJ, Paretsky DP. Blastomycosis: more evidence for exposure near one's domicile. WMJ. 2001;100(7):43-5.

29. Baumgardner DJ. Disease-causing fungi in homes and yards in the Midwestern United States. Journal of Patient-Centered Research and Reviews. 2016;3(2):99-110.

30. Pfister JR, Archer JR, Hersil S, Boers T, Reed KD, Meece JK, et al. Non-rural point source blastomycosis outbreak near a yard waste collection site. Clin Med Res. 2011 Jun;9(2):57-65.

31. Hoenigl M, Seidel D, Sprute R, Cunha C, Oliverio M, Goldman GH, et al. COVID-19-associated fungal infections. Nat Microbiol. 2022 Aug;7(8):1127-40.

32. McDonald R, Dufort E, Jackson BR, Tobin EH, Newman A, Benedict K, et al. Notes from the Field: Blastomycosis Cases Occurring Outside of Regions with Known Endemicity - New York, 2007-2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018 Sep 28;67(38):1077-78.

33. Fan D, Ahmad A, Frisby J, Darji K, Ojeaga A, Behshad R, et al. Classical Presentation of Disseminated Blastomycosis in a 44-Year-Old Healthy Man 3 Months After Diagnosis of COVID-19. Am J Case Rep. 2023 Apr 22;24:e938659.

34. Gadre A, Enbiale W, Andersen LK, Coates SJ. The effects of climate change on fungal diseases with cutaneous manifestations: A report from the International Society of Dermatology Climate Change Committee. The Journal of Climate Change and Health. 2022 May 1;6:100156.

35. Arnett MV, Fraser SL, Grbach VX. Pulmonary blastomycosis diagnosed in Hawai'i. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2008 Jul;39(4):701-5.

36. Cheikh Rouhou S, Racil H, Ismail O, Trabelsi S, Zarrouk M, Chaouch N, et al. Pulmonary blastomycosis: a case from Africa. ScientificWorldJournal. 2008 Nov 2;8:1098-103.

37. Richels L, Holfeld K. An uncommon infectious etiology in an unlikely geographic location: A case report of cutaneous blastomycosis in Saskatchewan. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2019 Dec 30;7:2050313X19897716.

38. Armstrong CW, Jenkins SR, Kaufman L, Kerkering TM, Rouse BS, Miller GB Jr. Common-source outbreak of blastomycosis in hunters and their dogs. J Infect Dis. 1987 Mar;155(3):568-70.

39. Pappas PG, Pottage JC, Powderly WG, Fraser VJ, Stratton CW, McKenzie S, et al. Blastomycosis in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1992 May 15;116(10):847-53.

40. Pappas PG. Blastomycosis in the immunocompromised patient. Semin Respir Infect. 1997 Sep;12(3):243-51.

41. Pappas PG, Threlkeld MG, Bedsole GD, Cleveland KO, Gelfand MS, Dismukes WE. Blastomycosis in immunocompromised patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1993 Sep;72(5):311-25.

42. Davar K, Jeng A, Donovan S. Burying Hatchets into Endemic Diagnoses: Disseminated Blastomycosis from a Potentially Novel Occupational Exposure. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2023 Jul 18;8(7):371.

43. Anderson JL, Meece JK. Molecular detection of Blastomyces in an air sample from an outbreak associated residence. Med Mycol. 2019 Oct 1;57(7):897-99.

44. Fanella S, Skinner S, Trepman E, Embil JM. Blastomycosis in children and adolescents: a 30-year experience from Manitoba. Med Mycol. 2011 Aug;49(6):627-32.

45. Wood C, Arviso L, Rokadia H, et al. Fungal Infectious Masquerading as Sarcoidosis. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine.2018;197:A5396. https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/epdf/10.1164/ajrccm-conference.

46. Linder KA, Kauffman CA. Current and new perspectives in the diagnosis of blastomycosis and histoplasmosis. Journal of Fungi. 2021 Jan;7(1):12.

47. Sterkel AK, Mettelman R, Wüthrich M, Klein BS. The unappreciated intracellular lifestyle of Blastomyces dermatitidis. J Immunol. 2015 Feb 15;194(4):1796-805.

48. Burton KA, Karulf M. Necrotizing Pneumonia Secondary to Pulmonary Blastomycosis: A Case Report. Cureus. 2023 May 10;15(5):e38846.

49. Krumpelbeck E, Tang J, Ellis MW, Georgescu C. Disseminated blastomycosis with cutaneous lesions mimicking tuberculosis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018 Dec;18(12):1410.

50. Eldaabossi S, Saad M, Aljawad H, Almuhainy B. A rare presentation of blastomycosis as a multi-focal infection involving the spine, pleura, lungs, and psoas muscles in a Saudi male patient: a case report. BMC Infect Dis. 2022 Mar 7;22(1):228.

51. David P, Varghese P, Bonwit A, Sharma A. A Case of Multifocal Necrotizing Blastomycosis Pneumonia and Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) in an Adolescent with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. Pediatrics. 2022 Feb 23;149(1 Meeting Abstracts February 2022):390.

52. Ajmal M, Aftab Khan Lodhi F, Nawaz G, Basharat A, Aslam A. Blastomycosis-Induced Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Cureus. 2022 Feb 14;14(2):e22207. doi: 10.7759/cureus.22207.

53. O'Dowd TR, Mc Hugh JW, Theel ES, Wengenack NL, O'Horo JC, Enzler MJ, et al. Diagnostic Methods and Risk Factors for Severe Disease and Mortality in Blastomycosis: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J Fungi (Basel). 2021 Oct 20;7(11):888.

54. Benedict K, Hennessee I, Gold JAW, Smith DJ, Williams S, Toda M. Blastomycosis-Associated Hospitalizations, United States, 2010-2020. J Fungi (Basel). 2023 Aug 22;9(9):867.

55. Fang W, Washington L, Kumar N. Imaging manifestations of blastomycosis: a pulmonary infection with potential dissemination. Radiographics. 2007 May-Jun;27(3):641-55.

56. Vasquez JE, Mehta JB, Agrawal R, Sarubbi FA. Blastomycosis in northeast Tennessee. Chest. 1998 Aug;114(2):436-43.

57. Gray NA, Baddour LM. Cutaneous inoculation blastomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002 May 15;34(10):E44-9.

58. Landay ME, Schwarz J. Primary cutaneous blastomycosis. Arch Dermatol. 1971 Oct;104(4):408-9.

59. Melton M, Baquerizo Nole K. Primary Cutaneous Blastomycosis: An Ulcerated Wound in an Immunocompetent Patient. Cureus. 2023 Sep 22;15(9):e45786.

60. Ortega-Loayza AG, Nguyen T. Cutaneous blastomycosis: a clue to a systemic disease. An Bras Dermatol. 2013 Mar-Apr;88(2):287-9.

61. Gilchrist TC, Stokes WR. A case of pseudo-lupus vulgaris caused by a Blastomyces. J Exp Med. 1898 Jan 1;3(1):53-78.

62. Caldito EG, Antia C, Petronic-Rosic V. Cutaneous Blastomycosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2022 Sep 1;158(9):1064

63. Sapra A, Pham D, Ranjit E, Baig MQ, Hui J. A Curious Case of Blastomyces Osteomyelitis. Cureus. 2020 Mar 25;12(3):e7417.

64. Pariseau B, Lucarelli MJ, Appen RE. A concise history of ophthalmic blastomycosis. Ophthalmology. 2007 Nov;114(11):e27-32.

65. Azam F, Hicks WH, Pernik MN, Hoes K, Payne R. Retropharyngeal Blastomycosis Abscess Causing Osteomyelitis, Discitis, Cervical Deformity, and Cervical Epidural Abscess: A Case Report. Cureus. 2023 Sep 19;15(9):e45570.

66. Meyer KC, McManus EJ, Maki DG. Overwhelming pulmonary blastomycosis associated with the adult respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1993 Oct 21;329(17):1231-6.

67. Patel AJ, Gattuso P, Reddy VB. Diagnosis of blastomycosis in surgical pathology and cytopathology: correlation with microbiologic culture. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010 Feb;34(2):256-61.

68. Morjaria S, Otto C, Moreira A, Chung R, Hatzoglou V, Pillai M, et al. Ribosomal RNA gene sequencing for early diagnosis of Blastomyces dermatitidis infection. Int J Infect Dis. 2015 Aug;37:122-4.

69. Valero C, Martín-Gómez MT, Buitrago MJ. Molecular Diagnosis of Endemic Mycoses. J Fungi (Basel). 2022 Dec 30;9(1):59.

70. Smith DJ, Free RJ, Thompson GR 3rd, Baddley JW, Pappas PG, Benedict K, et al. Clinical Testing Guidance for Coccidioidomycosis, Histoplasmosis, and Blastomycosis in Patients With Community-Acquired Pneumonia for Primary and Urgent Care Providers. Clin Infect Dis. 2024 Jun 14;78(6):1559-1563.

71. Durkin M, Witt J, Lemonte A, Wheat B, Connolly P. Antigen assay with the potential to aid in diagnosis of blastomycosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2004 Oct;42(10):4873-5.

72. Turner S, Kaufman L, Jalbert M. Diagnostic assessment of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for human and canine blastomycosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1986 Feb;23(2):294-7.

73. Klein BS, Vergeront JM, Kaufman L, Bradsher RW, Kumar UN, Mathai G, et al. Serological tests for blastomycosis: assessments during a large point-source outbreak in Wisconsin. J Infect Dis. 1987 Feb;155(2):262-8.

74. Connolly P, Hage CA, Bariola JR, Bensadoun E, Rodgers M, Bradsher RW Jr, et al. Blastomyces dermatitidis antigen detection by quantitative enzyme immunoassay. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2012 Jan;19(1):53-6.

75. Baumgardner DJ. Disease-causing fungi in homes and yards in the Midwestern United States. Journal of Patient-Centered Research and Reviews. 2016;3(2):99-110.

76. Kitchen MS, Reiber CD, Eastin GB. An urban epidemic of North American blastomycosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1977 Jun;115(6):1063-6.

77. Sarosi GA, Davies SF, Phillips JR. Self-limited blastomycosis: a report of 39 cases. Semin Respir Infect. 1986 Mar;1(1):40-4

78. Anderson JL, Frost HM, Meece JK. Spontaneous resolution of blastomycosis symptoms caused by B. dermatitidis. Med Mycol Case Rep. 2020 Oct 24;30:43-5.

79. Chapman SW, Dismukes WE, Proia LA, Bradsher RW, Pappas PG, Threlkeld MG, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of blastomycosis: 2008 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2008 Jun 15;46(12):1801-12.

80. Plamondon M, Lamontagne F, Allard C, Pépin J. Corticosteroids as adjunctive therapy in severe blastomycosis-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome in an immunosuppressed patient. Clin Infect Dis. 2010 Jul 1;51(1):e1-3.

81. Smith JA, Kauffman CA. Blastomycosis. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2010 May;7(3):173-80.

82. Anderson JL, Meece JK, Hall MC, Frost HM. Evidence of delayed dissemination or re-infection with Blastomyces in two immunocompetent hosts. Med Mycol Case Rep. 2016 Sep 14;13:9-11.

83. Meece JK, Anderson JL, Fisher MC, Henk DA, Sloss BL, Reed KD. Population genetic structure of clinical and environmental isolates of Blastomyces dermatitidis, based on 27 polymorphic microsatellite markers. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011 Aug;77(15):5123-31.

84. Baumgardner DJ. Disease-causing fungi in homes and yards in the Midwestern United States. Journal of Patient-Centered Research and Reviews. 2016;3(2):99-110.

85. Carlos WG, Rose AS, Wheat LJ, Norris S, Sarosi GA, Knox KS, et al. Blastomycosis in indiana: digging up more cases. Chest. 2010 Dec;138(6):1377-82.

86. Cuddapah GV, Malik MZ, Arremsetty A Jr, Fagelman A. A Case of Blastomyces dermatitidis Diagnosed Following Travel to Colorado: A Case Report and Review of Literature. Cureus. 2023 Sep 5;15(9):e44733.

87. Watts B, Argekar P, Saint S, Kauffman CA. Clinical problem-solving. Building a diagnosis from the ground up--a 49-year-old man came to the clinic with a 1-week history of suprapubic pain and fever. N Engl J Med. 2007 Apr 5;356(14):1456-62.