Abstract

Objectives: The use of generative artificial intelligence (AI) in psychiatric practice is becoming increasingly prevalent; however, some professionals still refuse to adopt AI tools. This study analyzes the attitudes of five psychiatrists who do not use AI and explores the reasons behind their decision.

Methods: Case series, 5 cases. Respondents were answering a structured questionnaire addressing trust in AI, ethical dilemmas, potential risks, and institutional support.

Results: The main reasons for not using AI include a lack of trust in information provided by AI, fear of perpetuating biases or discrimination in decision making processes, fear of the possibility of AI being used for malicious purposes, ethical concerns regarding patient relationships, fear of losing jobs due to AI, and insufficient institutional support for integrating AI into work. Most respondents express concern about the potential misuse of AI for malicious purposes. None of the respondents uses AI in their work or recommends AI solutions to patients. They discuss the use of AI with their colleagues. Only one believes it is possible to form an emotional connection with AI.

Conclusion: This case series offers a nuanced understanding of the barriers to adopting generative AI in psychiatric practice, particularly among professionals who have opted not to use such tools. The findings highlight that resistance to AI integration is shaped by a complex interplay of factors: lack of trust in the information provided by AI, concerns about perpetuating biases or discrimination through algorithmic decision-making, fears regarding potential misuse of AI for malicious purposes, apprehension about job loss due to AI, and insufficient institutional support for implementation.

While most respondents reported discussing the use of AI with their colleagues, only one expressed the belief that it is possible to form an emotional connection with AI. To overcome these barriers, a comprehensive approach is required—one that combines targeted education with robust institutional support. Such efforts are essential to build trust and confidence among clinicians and to ensure that the integration of AI tools upholds clinical integrity and prioritizes patient-centered care.

Introduction

The integration of generative artificial intelligence (AI) into psychiatric practice has gained increasing attention in recent years, with proponents highlighting its potential to improve diagnostics, streamline administrative tasks, and expand access to mental health services [1]. AI-powered chatbots, predictive algorithms, and decision-support tools are already being utilized in various clinical and research contexts [1].

Some researchers state that the hallmark of future public health education will be a symbiotic relationship between AI and education [2]. Predictive analytics will assist in forecasting and addressing the needs of public health workers, while AI-driven content customization will ensure that educational materials remain at the forefront of current and future public health challenges. The emergence of interactive and immersive learning experiences through AR/VR and AI will further solidify technology’s role in shaping the skills and competencies of future public health professionals [2].

Despite the optimism surrounding these developments, there is a growing body of literature pointing to persistent skepticism among mental health professionals. Mental health professionals must be prepared not only to use AI but also to have conversations about it when delivering care [3].

Patients with mental health conditions are among the most vulnerable, and they may be turning to generative AI to supplement or even replace health information and the emotional support traditionally derived from mental health clinicians and other health professionals [4]. Some research shows that current generative AI tools still present evidence-based risks, including inaccuracies, inconsistencies, hallucinations, and the potential to introduce harmful biases into clinical decision-making [4].

Other concerns range from ethical dilemmas and algorithmic bias to the erosion of human empathy in therapeutic relationships, and to assessing the potential risks and appropriate role of AI-powered genomic health prediction [5,6].

Close philosophical engagement is key to characterizing, identifying, and responding to harmful biases that can result from the simplistic adoption and use of predictive algorithms in our societies [7].

Moreover, popular media and recent investigations have raised alarms about the unregulated use of AI in mental health, including the rise of flawed AI-generated self-help content and mental health applications that may inadvertently cause harm [8]. One question being raised is whether a large language model (LLM) should be used as a therapist [9], along with a series of considerations grounded in the ethics of care for the developmental process of AI-powered therapeutic tools.

Before the release of increasingly task-autonomous AI systems in mental health, it is crucial to ensure that these models can reliably detect and manage symptoms of common psychiatric disorders to prevent harm to users [8].

Recent studies published since 2021 have expanded the understanding of clinician resistance to AI in psychiatry [10], showing that trust is an important factor in people's interactions with AI systems. However, there is a lack of empirical studies examining how real end-users trust or distrust the AI systems they interact with [10].

Given this tension between innovation and resistance, understanding the reasons behind clinicians’ refusal to adopt AI tools is of critical importance. Some research also highlights potential security threats from the malicious use of AI and proposes ways to better forecast, prevent, and mitigate these threats [11].

This study explores the perspectives of five psychiatrists who have chosen not to incorporate AI into their practice, aiming to uncover the psychological, institutional, and ethical considerations that inform their decisions. By examining these attitudes, the research seeks to contribute to a more balanced discourse and offer recommendations for the responsible and supportive integration of AI technologies in mental health care.

According to Yin [12] and Stake [13], case study research may yield valid insights even with a small number of cases when the objective is to explore depth and context rather than generalize.

Methodology

This study employs a case series design involving five individual cases. Each case represents a unique respondent who participated in a structured questionnaire. The questionnaire was designed to explore key themes including trust in artificial intelligence (AI), ethical dilemmas related to AI implementation, perceived potential risks, and the role of institutional support.

As Yin [12] and Stake [13] note, case study research aims for depth over breadth, and a small number of cases can be sufficient when the objective is to explore context-rich, individual perspectives.

Case Selection

From the broader pool of respondents from the pilot study investigating AI adoption in psychiatry, five individual cases were selected for detailed presentation. These five cases were not included in the pilot study. The main selection criterion that these five cases were now selected was that these participants reported not using AI in their work. This subgroup was intentionally chosen now to explore how individuals who have not personally engaged with generative AI perceive it in terms of trust, ethical concerns, and perceived risks. Highlighting non-users provides valuable insight into barriers to adoption, potential misconceptions, and attitudes shaped by indirect experience or broader societal narratives, rather than firsthand use.

AI-Assisted Editing Contribution

In this this case series, the AI tool ChatGPT was utilized as a supportive resource for text revision, particularly in improving linguistic accuracy, clarity, and consistency throughout the manuscript. The AI-assisted editing focused on enhancing sentence structure, grammar, and flow, ensuring that the text adhered to appropriate academic standards. It is important to note that the role of AI was strictly confined to assisting with the refinement of language and did not extend to making scientific interpretations, formulating conclusions, or altering the research's core content. The AI's contribution was limited to the mechanical and stylistic aspects of writing, ensuring that the final manuscript was polished and professionally presented, while the intellectual and analytical aspects of the research remained solely under the author's responsibility.

Results

Age, gender and country of origin of five cases is shown in Table 1. The five participants included three women and two men, aged between 41 and 69. Three participants were from Denmark and two from Croatia.

|

Age |

Gender |

Country of origin |

|---|---|---|

|

67 |

Man |

Denmark |

|

41 |

Woman |

Denmark |

|

56 |

Woman |

Croatia |

|

42 |

Woman |

Croatia |

|

69 |

Man |

Denmark |

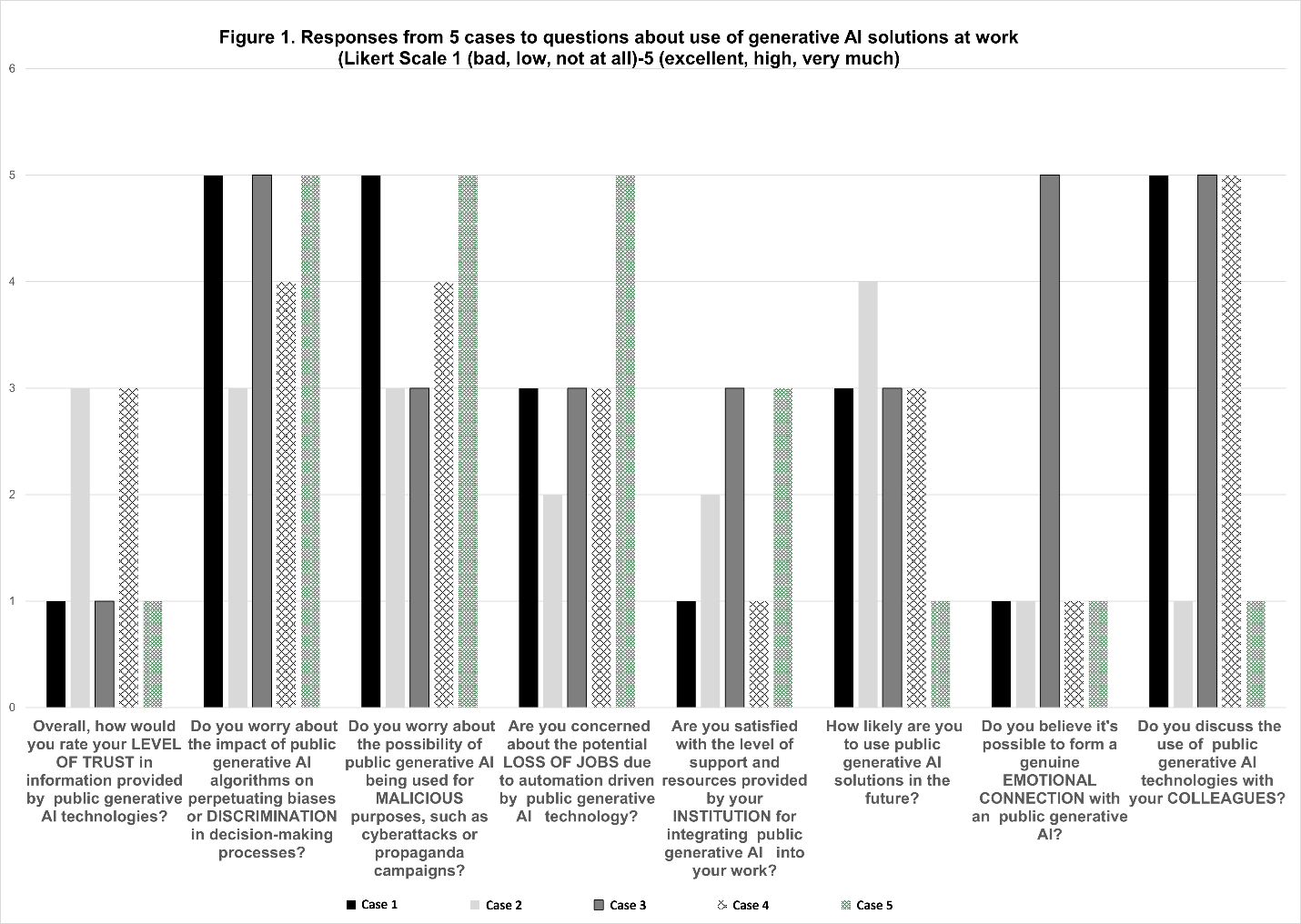

Results from responses from five cases to questions about use of generative AI solutions at work (Likert Scale 1 [bad, low, not at all] -5 [excellent, high, very much]) are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Responses from 5 cases to questions about use of generative AI solutions at work (Likert Scale 1 [bad, low, not at all] -5 [excellent, high, very much]).

The main reasons for not using AI include:

- Lack of trust in the information provided by AI

- Fear of perpetuating biases or discrimination in decision-making processes

- Concern about the potential misuse of AI for malicious purposes, including cyberattacks and cyber propaganda

- Fear of job loss due to AI

- Insufficient institutional support for integrating AI into the workplace

- Most respondents discuss the use of AI with their colleagues

- Only one respondent believes it is possible to form an emotional connection with AI.

Discussion

This case series offers a unique insight into the reasons why some psychiatrists choose not to use AI—an aspect that remains underexplored in the existing literature.

The decision to focus on individuals who do not use AI tools, specifically ChatGPT, was informed by previous research highlighting the importance of understanding barriers to AI adoption.

The findings of this case series further emphasize several key barriers that hinder the adoption of generative AI technologies among psychiatrists.

One significant barrier identified is the lack of trust in the accuracy and reliability of AI-generated information, which echoes concerns found in prior literature [10,14]. According to Kim [10], trust in AI is influenced by numerous factors. Human-related factors include domain knowledge and derived abilities such as assessing AI outputs, evaluating AI capabilities, and using AI effectively. AI-related factors include internal attributes such as ability, integrity, and benevolence; external factors such as popularity; and user-dependent factors such as familiarity and ease of use. Context-related factors encompass task difficulty, perceived risks and benefits, other situational characteristics, and the reputation of the domain and developers [10].

Furthermore, Banovic et al. [15] argue that AI systems may gain users’ trust even when they are not trustworthy. Both unwarranted trust (trusting when the AI system is not trustworthy) and unwarranted distrust (distrusting when the AI system is trustworthy) can compromise the quality of human–AI interactions [15]. Trustworthy AI is characterized, among other things, by (1) competence, (2) transparency, and (3) fairness [15]. Their research also demonstrated that participants were often unable to assess AI competence accurately, placing trust in untrustworthy systems and thereby confirming AI’s potential to deceive [15].

This skepticism is compounded by fears that AI algorithms may perpetuate or even amplify biases in clinical decision-making. Previous research shows that algorithmic bias can reinforce structural inequalities within mental healthcare [7]. Algorithmic decision-making is increasingly common—and increasingly controversial [16]. Critics argue that such tools lack transparency, accountability, and fairness. Assessing fairness is particularly complex, as it requires consensus on what fairness entails [16].

To the question “What can or should we do about algorithmic biases?” one common response, according to Fazelpour et al. [7], is to assert that “algorithms ought not use sensitive information about group membership.” The rationale is that an algorithm cannot be biased about property X if it is never informed whether an individual possesses X. For example, to reduce racial bias in a student success prediction algorithm, developers might remove racial identifiers from training data. In the U.S. legal system, this “fairness through unawareness” approach is typically grounded in anti-classification principles aimed at preventing discrimination. Explicit use of protected attributes—such as race, gender, and nationality—often triggers strict scrutiny by U.S. courts [16]. Unfortunately, this approach almost never succeeds [7]. Similarly, better measurement strategies may lead to fairer algorithms [16], but they still fail to address many other sources of bias.

Several authors argue that technical solutions alone are insufficient, as they overlook the social and structural origins of inequality. Philosophical and ethical analyses are therefore also essential [17].

Prior literature further emphasizes that reluctance to use AI is not solely rooted in ignorance or fear of technology, but in legitimate professional, emotional, and institutional concerns [18]. Addressing these barriers will require targeted efforts in education, ethical regulation, and institutional support to ensure that AI implementation in psychiatry respects both clinical integrity and patient care [18]. One promising approach is “human-in-the-loop” machine learning, which utilizes active learning to select the most critical data needed to enhance model accuracy and generalizability more efficiently than random sampling [18]. This method can also serve as a safeguard against spurious predictions and help reduce the disparities that AI systems might otherwise perpetuate [18].

Ethical concerns about the misuse of AI—particularly its potential applications for malicious purposes, cyberattacks, and cyber propaganda—also emerged in this case series as a prominent barrier to the adoption of generative AI technologies among psychiatrists. These concerns align with ongoing public debates regarding the regulation and transparency of AI tools in mental health settings [19].

Other research shows that, from an ethical perspective, important benefits of embodied AI applications in mental health include new modes of treatment, opportunities to engage hard-to-reach populations, better patient responses, and freeing up time for physicians [20]. Overarching ethical issues and concerns include harm prevention and various questions of data ethics; a lack of guidance on the development of AI applications, their clinical integration, and training of health professionals; gaps in ethical and regulatory frameworks; and the potential for misuse, including replacing established services and thereby exacerbating existing health inequalities [20]. Specific challenges identified in the application of embodied AI include risk assessment, referrals, and supervision; the need to respect and protect patient autonomy; the role of non-human therapy; transparency in the use of algorithms; and concerns regarding the long-term effects of these applications on understandings of illness and the human condition [20].

As artificial intelligence becomes increasingly capable and accessible, Brundage et al. [11] anticipate a transformation in the threat landscape. The scalability of AI is likely to lower the cost of executing attacks that would normally require significant human resources. This may empower a broader range of malicious actors, accelerate the frequency of attacks, and broaden the scope of targets. Furthermore, AI could enable entirely new forms of attacks previously unfeasible for humans, and adversaries may exploit vulnerabilities within AI systems themselves, making such threats harder to detect, attribute, and defend against [11].

Brundage et al. [11] illustrate potential changes in threats across three domains:

- Digital security: AI can automate tasks in cyberattacks, removing the tradeoff between scale and effectiveness. This may increase threats such as spear phishing, automated hacking, exploitation of human vulnerabilities (e.g., speech synthesis for impersonation), and vulnerabilities in AI systems themselves (e.g., adversarial examples and data poisoning).

- Physical security: AI enables the automation of attacks using drones and autonomous weapons, expanding the threat posed by these attacks. New attacks may involve cyber-physical systems (e.g., causing autonomous vehicles to crash) or swarms of micro-drones that are otherwise infeasible to control remotely.

- Political security: AI can automate surveillance, create targeted propaganda, and manipulate video, increasing the risks of privacy invasion and social manipulation. Enhanced analysis of human behavior can facilitate such attacks, posing particular dangers in authoritarian regimes while also undermining democratic debate [11].

To mitigate these threats, Brundage et al. [11] recommend four priority research and action areas:

- Learning from the cybersecurity community, including red teaming and responsible disclosure of vulnerabilities;

- Exploring openness models in research with risk assessment and regulated access;

- Promoting a culture of responsibility among researchers and organizations;

- Developing technical and policy solutions, including privacy protection, coordinated use of AI for security, and regulatory measures.

These measures require collaboration among researchers, companies, legislators, and regulators, as the challenges are significant and the stakes high [11].

Additionally, one participant in the case series described the possibility of forming an emotional bond with AI as a barrier to adoption—an idea still widely debated in the literature. The role of AI in mental health extends to potentially replacing certain functions traditionally performed by human psychotherapists [21]. Innovations in machine learning and natural language processing have enabled AI systems like ChatGPT to recognize and process complex human emotions, facilitating interactions that once required the nuanced understanding of trained therapists [22,23].

Other research demonstrated generally positive perceptions and opinions among patients about mental health chatbots [24]. However, several issues need to be addressed, including the chatbots’ ability to handle unexpected user input, provide high-quality and varied responses, and support individualized treatment. Personalization of chatbot conversations is essential to clinical usefulness [24].

Conversely, other studies found that many participants doubted AI’s ability to provide empathetic and thoughtful responses—a critical component of effective mental health care [25]. According to research by Lee et al. [26], some participants expressed concern that AI conversational agents might be perceived as replacements for traditional therapy, which they believed could be dangerous. A minority felt that no human involvement was necessary, emphasizing the value of anonymity in overcoming stigma or fear of judgment [26].

Our case series also found that institutional and structural barriers significantly contribute to low AI adoption rates. Respondents reported dissatisfaction with the level of support and resources provided by institutions for integrating AI into their work. This finding supports prior research suggesting that successful implementation of AI in psychiatry depends not only on the technology itself but also on organizational readiness and clinician education [2,5]. Addressing these concerns will require a multifaceted approach, including transparent AI design, improved clinician training, and the development of policy frameworks that safeguard both patients and professionals. Previous research also revealed divergent views among psychiatrists about the value and impact of future technologies, with notable concerns about the lack of practice guidelines, as well as ethical and regulatory clarity [14].

Ultimately, this case series demonstrates that resistance to AI adoption in psychiatric settings is not merely a result of individual technophobia. Rather, it reflects a complex interplay of professional, emotional, and institutional factors. To overcome these barriers, a comprehensive approach is needed—one that involves clinician education and institutional support to foster trust and ensure that AI tools are integrated in ways that respect clinical integrity and patient care.

Our case series also found that a key barrier inhibiting the adoption of generative AI technologies among psychiatrists is the fear of losing jobs due to AI. In other surveys, psychiatrists were not significantly worried about job loss caused by AI [27]. The survey included 791 psychiatrists from 22 countries across North America, South America, Europe, and the Asia-Pacific region. Only 3.8% of respondents felt it was likely that future technologies would make their jobs obsolete, and just 17% believed that AI or machine learning would likely replace a human clinician in providing empathetic care [27].

Other research shows that artificial intelligence systems impact the tasks of mental healthcare workers primarily by providing support and enabling deeper insights. Most systems are designed to assist rather than replace mental health professionals. These results highlight the importance of training professionals to enable hybrid intelligence [28].

According to Kolding et al. [29], the integration of generative AI into mental healthcare is rapidly evolving. The literature mainly focuses on applications such as ChatGPT and finds that generative AI performs well, though it remains limited by significant safety and ethical concerns. Future research should strive to improve methodological transparency, adopt experimental designs, ensure clinical relevance, and involve users or patients in the design phase [29].

Previous research [3] showed that while numerous digital tools, online platforms, and mobile applications have been developed using AI technologies, the mental health field has generally been more cautious and slower in adopting such innovations. The findings suggest implications on three levels [3]. On the individual level, it is essential for digital professionals to recognize the importance of AI tools that maintain empathy and a person-centered approach. For mental health practitioners, overcoming hesitancy toward AI requires targeted educational efforts to increase awareness of its usefulness, feasibility, and benefits. On the organizational level, collaboration between digital experts and leadership is necessary to establish effective governance structures and secure funding that promotes staff engagement. Finally, on the broader societal level, coordinated efforts between digital and mental health professionals are required to develop formal AI training programs tailored to the needs of the mental health sector and to bridge existing knowledge gaps [3].

Limitations of study

This this case series is limited by its small sample size and the focus on two countries only. Future research should include a more diverse and larger sample and explore changes in attitudes over time or in relation to professional training in AI. Further quantitative studies could assess how these attitudes correlate with institutional readiness and exposure to AI technologies.

Conclusion

This case series offers a nuanced understanding of the barriers to adopting generative AI in psychiatric practice, particularly among professionals who have opted not to use such tools. The findings highlight that resistance to AI integration is shaped by a complex interplay of factors: lack of trust in the information provided by AI, concerns about perpetuating biases or discrimination through algorithmic decision-making, fears regarding potential misuse of AI for malicious purposes, apprehension about job loss due to AI, and insufficient institutional support for implementation.

While most respondents reported discussing the use of AI with their colleagues, only one expressed the belief that it is possible to form an emotional connection with AI. To overcome these barriers, a comprehensive approach is required—one that combines targeted education with robust institutional support. Such efforts are essential to build trust and confidence among clinicians and to ensure that the integration of AI tools upholds clinical integrity and prioritizes patient-centered care.

References

2. Wang J, Li J. Artificial intelligence empowering public health education: prospects and challenges. Front Public Health. 2024 Jul 3;12:1389026.

3. Zhang M, Scandiffio J, Younus S, Jeyakumar T, Karsan I, Charow R, et al. The adoption of AI in mental health care–perspectives from mental health professionals: qualitative descriptive study. JMIR Formative Research. 2023 Dec 7;7(1):e47847.

4. Blease C, Rodman A. Generative artificial intelligence in mental healthcare: An ethical evaluation. Curr Treat Options Psych. 2025;12:5.

5. Luxton DD. Artificial intelligence in behavioral and mental health care. London: Academic Press; 2016.

6. Nuffield Council on Bioethics. Artificial intelligence (AI) in healthcare and research. https://cdn.nuffieldbioethics.org/wp-content/uploads/Ada-NCOB-Report-Predicting-The-future-of-health.pdf

7. Fazelpour S, Danks D. Algorithmic bias: Senses, sources, solutions. Philosophy Compass. 2021;16(6):e12731.

8. Grabb D, Lamparth M, Vasan N. Risks from language models for automated mental healthcare: Ethics and structure for implementation (Version 2). arXiv Preprint. arXiv.2406.11852. 2024, August 14.

9. Moore J, Grabb D, Agnew W, Klyman K, Chancellor S, Ong DC, et al. Expressing stigma and inappropriate responses prevents LLMs from safely replacing mental health providers. arXiv Preprint. arXiv.2504.18412. 2025, April 25.

10. Kim SS, Watkins EA, Russakovsky O, Fong R, Monroy-Hernández A. Humans, AI, and Context: Understanding End-Users' Trust in a Real-World Computer Vision Application. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.08598. 2023 May 15.

11. Brundage M, Avin S, Clark J, Toner H, Eckersley P, Garfinkel B, et al. The malicious use of artificial intelligence: Forecasting, prevention, and mitigation (Version 2). arXiv preprint. arXiv.1802.07228. 2024.

12. Yin RK. Case study research and applications. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2018.

13. Stake RE. The art of case study research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1995.

14. Blease C, Locher C, Leon-Carlyle M, Doraiswamy M. Artificial intelligence and the future of psychiatry: qualitative findings from a global physician survey. Digital Health. 2020 Oct; 6:2055207620968355.

15. Banovic N, Yang Z, Ramesh A, Liu A. Being trustworthy is not enough: How untrustworthy artificial intelligence (AI) can deceive the end-users and gain their trust. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction. 2023;7(CSCW1):27.

16. Hellman D. Measuring algorithmic fairness. Virginia Law Review. 2020;106(4):811–66.

17. Selbst AD, Boyd D, Friedler SA, Venkatasubramanian S, Vertesi J. Fairness and abstraction in sociotechnical systems. In: Proceedings of the Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency. 2019 Jan 29; pp. 59–68.

18. Chandler C, Foltz PW, Elvevåg B. Improving the applicability of AI for psychiatric applications through human-in-the-loop methodologies. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2022 Sep 1; 48(5):949–57.

19. Tavory T. Regulating AI in Mental Health: Ethics of Care Perspective. JMIR Ment Health. 2024 Sep 19;11:e58493.

20. Fiske A, Henningsen P, Buyx A. Your Robot Therapist Will See You Now: Ethical Implications of Embodied Artificial Intelligence in Psychiatry, Psychology, and Psychotherapy. J Med Internet Res. 2019 May 9;21(5):e13216.

21. Zhang Z. Can AI replace psychotherapists? Exploring the future of AI in mental health. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2024;15:1444382.

22. Elyoseph Z, Hadar-Shoval D, Asraf K, Lvovsky M. ChatGPT outperforms humans in emotional awareness evaluations. Front Psychol. 2023 May 26;14:1199058.

23. Cheng SW, Chang CW, Chang WJ, Wang HW, Liang CS, Kishimoto T, Chang JP, Kuo JS, Su KP. The now and future of ChatGPT and GPT in psychiatry. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2023 Nov;77(11):592–6.

24. Abd-Alrazaq AA, Alajlani M, Ali N, Denecke K, Bewick BM, Househ M. Perceptions and opinions of patients about mental health chatbots: Scoping review. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2021;23:e17828.

25. Boucher EM, Harake NR, Ward HE, Stoeckl SE, Vargas J, Minkel J, et al. Artificially intelligent chatbots in digital mental health interventions: A review. Expert Review of Medical Devices. 2021;18(1):37–49.

26. Lee HS, Wright C, Ferranto J, Buttimer J, Palmer CE, Welchman A, Mazor KM, Fisher KA, Smelson D, O'Connor L, Fahey N, Soni A. Artificial intelligence conversational agents in mental health: Patients see potential, but prefer humans in the loop. Front Psychiatry. 2025 Jan 31;15:1505024.

27. Doraiswamy PM, Blease C, Bodner K. Artificial intelligence and the future of psychiatry: Insights from a global physician survey. Artif Intell Med. 2020 Jan;102:101753.

28. Rebelo AD, Verboom DE, dos Santos NR, de Graaf JW. The impact of artificial intelligence on the tasks of mental healthcare workers: A scoping review. Computers in Human Behavior: Artificial Humans. 2023 Aug 1;1(2):100008.

29. Kolding S, Lundin RM, Hansen L, Østergaard SD. Use of generative artificial intelligence (AI) in psychiatry and mental health care: a systematic review. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2024 Nov 11;37:e37.