Abstract

Diabetic retinopathy is a leading cause of blindness in diabetic patients, and its onset and progression are influenced by inflammation. This article provides an overview of local inflammatory biomarker research in diabetic retinopathy, covering serum, aqueous humor, vitreous inflammatory factors, and retinal inflammation markers. Through a systematic review and analysis, we found that inflammatory biomarkers play a crucial role in the prediction, diagnosis, and treatment of diabetic retinopathy, as well as in understanding its pathological mechanisms and improving clinical diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. Future research should further investigate the role of inflammatory biomarkers in diabetic retinopathy to develop more effective strategies for early intervention and treatment of related diseases.

Keywords

Inflammation, Inflammatory factors, Diabetes, Diabetic retinopathy

Introduction

With improving living standards, dietary habits have changed, contributing to an annual rise in the prevalence of diabetes mellitus (DM). Diabetes imposes a growing global burden. The IDF Diabetes Atlas 10th edition (2021) estimated 537 million (10.5%) adults aged 20–79 living with diabetes, projected to 783 million by 2045 [1]. These trends underscore the unmet need for early detection and individualized risk stratification in diabetic retinopathy (DR). DR is a common microvascular complication in diabetic patients, strongly linked to socioeconomic status [2,3]. In developing countries, DR has emerged as a major public health issue and is the leading cause of visual impairment and blindness among the working-age population [4].

While the relationship between glycemic control and the development and progression of DR is well-established, studies indicate that HbA1c levels account for only 11% of DR risk. The remaining 89% of the risk variation is attributed to diabetic environmental factors not reflected in mean HbA1c levels [5,6]. Inflammation was first proposed as a factor in DR pathogenesis in the last century, and numerous clinical studies have since confirmed its role as a key contributor to DR [7]. Elevated levels of several inflammatory cytokines have been detected in aqueous, vitreous, and retinal samples from DR patients. These mediators are strongly linked to the breakdown of the blood-retinal barrier and the development of retinal neovascularization [8]. Inflammation thus plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of DR. At present, DR diagnosis primarily relies on retinal examination [9]. Therefore, identifying biomarkers that can accurately diagnose DR, particularly in its early stages, offers significant clinical potential. Biomarkers are expected to improve diagnostic accuracy, facilitate screening of a broader population, and enhance early detection, leading to more effective management and treatment of DR [10,11]. This review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of biomarkers associated with diabetic retinopathy, with the goal of guiding clinical practice and future research.

Diabetic Retinopathy

DM is a group of metabolic disorders characterized by defective insulin secretion or impaired insulin action, leading to chronic hyperglycemia. Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) is an autoimmune disorder that destroys pancreatic β-cells, while type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is primarily driven by insulin resistance [12]. Regardless of type, chronic hyperglycemia causes damage to small blood vessels (less than 100 microns in diameter). This primarily affects the retina, ultimately resulting in visual impairment [13]. Patients are often asymptomatic until typical retinal lesions appear. In the early stages, retinal ganglion cell damage and diabetic microangiopathy are detected during screening [14].

DR results from damage to retinal capillaries caused by chronic hyperglycemia [15]. The retinal microvascular system mainly consists of peripapillary and endothelial cells [16], and their loss is the primary cytological manifestation of DR [17]. Early DR is characterized by microaneurysms and microhemorrhages. As the disease progresses, hard exudates, cotton-wool spots, vein beading, and intraretinal microvascular abnormalities (IRMAs) emerge, eventually advancing to proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR). PDR is a stage where fibrovascular membrane proliferation and retinal detachment may result in complete blindness [10].

Inflammation

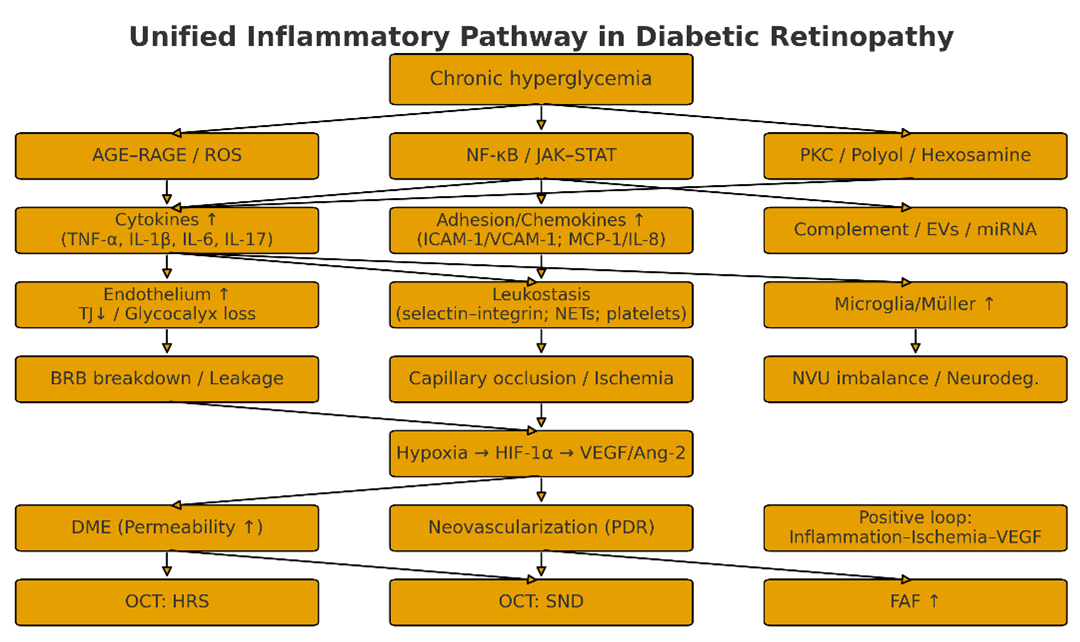

DR is not merely a microvascular disorder, but also a disease characterized by neurovascular unit (NVU) imbalance driven by chronic low-grade inflammation [18]. Prolonged hyperglycemia induces oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction via the AGE–RAGE, PKC, sorbitol and hexosamine pathways, activating transcription programs such as NF-κB, JAK/STAT, and MAPK. This process is accompanied by epigenetic “metabolic memory”, maintaining low-grade inflammation even after glycemic control is achieved [19]. Endothelial cells, Müller cells, and microglia release cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-17/23, secrete chemokines including MCP-1 and IL-8, and upregulate adhesion molecules such as ICAM-1, VCAM-1, and E-selectin; Complement C3a/C5a and the membrane attack complex (MAC) enhance permeability and cellular damage, whilst extracellular vesicles/miRNA further mediate inflammatory signaling between systemic and localized sites [20]. Consequently, endothelial activation and leukocyte adhesion (leukostasis), coupled with granulocyte/monocyte adhesion and retention releasing reactive oxygen species and proteases, superimposed upon platelet activation and NETs-induced microthrombus formation, result in hypoperfusion and areas of ischemia [21].Concurrently, downregulation of tight junction proteins (ZO-1, Occludin, Claudin-5), loss of glycocalyx, pericellular apoptosis and thickening of the basement membrane occur, leading to disruption and leakage of the blood-retinal barrier and the formation of diabetic macular oedema [22]. Ischemia stabilizes HIF-1α, driving the upregulation of VEGF/PlGF/Ang-2, which both exacerbates vascular permeability and induces neovascularization. This propels the progression from NPDR to PDR, forming a mutually reinforcing positive feedback loop with inflammation that constitutes the ‘inflammation-ischemia-angiogenesis’ cascade [23]. The sustained activation of microglia and disruption of glutamate homeostasis creates a bidirectional coupling between neuroinflammation and microvascular injury, explaining the early thinning of the ganglion cell layer/nerve fiber layer observed on imaging. At the systemic level, indices such as CRP, NLR, PLR, and SII/SIRI correlate with DR severity, suggesting coupling between systemic immune activation and the ocular microenvironment. Collectively, the inflammatory mechanisms of DR constitute an interventionable chain. In practice, the integration of multi-indicator panels with multi-modal imaging holds promise for achieving early screening, stratified diagnosis, and personalized treatment.

Figure 1. Unified inflammatory pathway in diabetic retinopathy.

Relationship between Inflammatory Markers and DR

The development of DR is strongly associated with chronic inflammation [24]. Various inflammatory markers have been identified in DR patients, and their levels correlate with the severity and prognosis of the disease. The pathophysiology of DR involves hyperglycemia, oxidative stress, inflammation, and vascular endothelial dysfunction, ultimately resulting in retinal nerve and vascular damage [25]. Currently, clinical focus is primarily on vascular damage, while inflammatory responses are detected at early stages. This suggests that inflammation could be a key early event in DR development, potentially occurring even before vascular injury.

Systemic inflammatory indicators and DR

DM is a systemic condition in which blood biomarkers are closely linked to both the disease and the progression of its complications. While serological testing is invasive, it offers the advantages of simplicity and ease of use.

Systemic inflammatory biomarkers offer clear advantages in accessibility and cost. A panel combining TNF-α and IL-6 with adhesion molecules (sICAM-1, sVCAM-1, sE-selectin) aligns more closely with the pathogenic cascade, while CRP and blood-cell ratios/indices (e.g., NLR, PLR, SII, SIRI) are suitable as a first-line, clinic-friendly screen. However, clinical translation is limited by threshold heterogeneity, pre-analytical and platform variability, confounding from comorbidities and medications, and the paucity of multicenter prospective validation. We recommend harmonized SOPs and inter-laboratory quality assurance across cohorts, followed by external calibration and decision-curve analysis. Constructing a multi-marker framework that integrates a baseline layer (CRP, NLR/PLR, SII/SIRI), a mechanistic axis (TNF-α/IL-6 plus adhesion molecules), and imaging readouts, and reporting incremental AUC, NRI/IDI, and health-economic outcomes will clarify the true net clinical benefit for risk stratification, follow-up intervals, and treatment selection.

|

Biomarker (type) |

Sample |

Main association with DR /mechanism |

Key evidence |

Potential clinical use |

Limitations/notes |

|

TNF-α (cytokine) |

Serum |

Strongly associated with DR onset/progression; enhances leukocyte adhesion and retinal microvascular cell loss; anti-TNF reduces stasis/leakage/cell death |

[26–28] |

Candidate target for inflammatory phenotypes; activity/severity indicator |

Systemic adverse effects and indications must be weighed; inter-study heterogeneity |

|

IL-6 (cytokine) |

Serum |

Associated with PDR risk and disease activity; included in EURODIAB composite |

[32,34] |

Progression prediction and risk stratification |

Acute-phase reactant; limited specificity |

|

IL-1 (cytokine) |

Serum |

May predict PDR |

[33] |

Supplemental prognostic marker |

Fewer studies; thresholds not standardized |

|

sICAM-1 (adhesion) |

Serum |

Associated with DR; indicates endothelial activation/inflammation |

[35,36] |

Readout of inflammation/endothelial activation |

Influenced by comorbid inflammation and CV risk |

|

sVCAM-1 (adhesion) |

Serum |

Associated with DR; part of leukocyte adhesion cascade |

[35,36] |

Aid to activity assessment |

Same as above |

|

sE-selectin (adhesion) |

Serum |

Independently predicts incident DR in long-term follow-up |

[37] |

Long-term risk assessment |

Cut-offs/platforms vary; population differences |

Inflammatory indicators in vitreous fluid and DR

Vitreous fluid is a clear, colorless, jelly-like gel within the eye, composed primarily of water (98%–99%), collagen, hyaluronic acid, and electrolytes. It helps maintain the clarity and structure of the eye and is an avascular tissue, with most proteins originating from the retina. Currently, vitreous samples are typically obtained during eye surgery, with puncture biopsies performed less frequently when therapeutic drugs are injected into the vitreous cavity [41]. Although many studies have shown higher concentrations of markers in the vitreous compared to serum, a major limitation is the inability to obtain samples from normal subjects for control purposes.

IL-6 is an inflammatory cytokine that enhances leukocyte accumulation and macrophage activation [42]. Studies have shown that elevated IL-6 is detected in the vitreous fluid of PDR. Additionally, in vitro experiments have found that IL-6 neutralizing inhibitors reduce neovascularization in vitreous samples from PDR patients. However, IL-6 has also been detected in the vitreous of patients without PDR [43]; suggesting it may not be a specific marker for PDR.

TNF-α and IL-8 are detected at higher concentrations in the vitreous than in serum in both human and animal models of PDR [3]. This suggests that these immunoinflammatory factors are produced locally in the eye rather than being transported from the circulation. IL-8 is primarily produced in Müller cells, astrocytes, and retinal pigment epithelial cells. The ischemic and hypoxic state of the retina in PDR patients disrupts the balance between retinal vascular growth and inhibitory factors, leading to increased secretion of vitreous IL-8. This further exacerbates retinal ischemia and macrovascular glial occlusion, creating a vicious cycle [44]. Additionally, TNF-α induces connections between retinal pigment epithelial and vascular endothelial cells, disrupting the blood-retinal barrier and contributing to the transformation of the retina from a non-proliferative to a neovascular state, thereby exacerbating visual impairment [45]. IL-17 amplifies the immune response by triggering the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6 and TNF-α, thereby linking T-cell activation and inflammation [46]. IL-31 has been associated with various diseases, including allergic asthma, rhinitis, and Crohn’s disease [47]. It is produced by Th2 cells and detected in PDR vitreous samples, although its relationship with DR and its pathogenesis remains unclear.

|

Indicator |

Sample |

Main findings |

Key evidence |

Potential clinical use |

Limitations/ notes |

|

CRP (inflammatory marker) |

Serum |

Associated with microvascular complications; CRP genotype linked to higher DR risk in Chinese T2D (OR≈1.3); CRP level correlates with DR severity |

[29–31] |

Widely available, low-cost risk/severity assessment |

Non-specific; affected by infection, obesity, CV risk |

|

EURODIAB composite z-score (CRP + TNF-α + IL-6) |

Serum |

Composite score positively associated with vascular complication risk |

[34] |

Multi-marker panel for overall risk assessment |

Needs external calibration; computation steps vary |

|

NLR/PLR (blood cell ratios) |

CBC |

Elevated in DR; reflect balance of leukocyte subsets |

[40] |

Low-cost tools for early/initial screening |

Cut-offs vary across studies; influenced by infection/drugs |

|

SII/SIRI (composite inflammation indices) |

CBC |

Elevated in T2DM with DR; may aid early screening |

[40] |

Convenient systemic inflammation readouts |

No unified thresholds; prospective validation needed |

|

Circulating neutrophils and platelet activity |

Blood |

Higher in advanced DR |

[39] |

Indicators of activity/progression risk |

Confounded by comorbidities and treatments |

Inflammatory indicators in aqueous humor and DR

Aqueous humor sampling can be performed during cataract surgery or via anterior chamber puncture. Anterior chamber puncture biopsy is relatively simple and has been proposed as an alternative to vitreous biopsy. However, it has limitations, including: a small sample size, compositional changes if structures such as the iris are disturbed during sampling, and a potential for false-negative results [15]. Furthermore, comparisons between anterior chamber and vitreous proteins have shown significant differences in specific protein levels [48].

In patients with DR, the levels of aqueous humor IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, MCP-1, and IP-10 were higher than in those without DR and positively correlated with DR severity. In contrast, IL-10 and IL-12 levels were significantly reduced in the aqueous humor of patients with DR [10]. Additionally, IL-17 and IL-23 concentrations are elevated in the aqueous humor of DR patients. IL-17 promotes the release of inflammatory factors from various cells, stimulating inflammatory cell accumulation and ultimately causing pathological damage to the retinal vasculature. IL-23, in turn, promotes IL-17 secretion, activating the IL-23/IL-17 pathway and triggering an inflammatory cascade response [49].

There is no direct communication between aqueous humor and vitreous humor. Studies have shown that IL-8 levels in aqueous humor are significantly higher than those in vitreous humor in patients with PDR [44]. Although the exact cause remains unclear, this finding has significant implications for the future selection of samples in inflammatory marker detection. Further investigation is needed to explore the specific mechanisms of these cytokines in DR progression and their potential as therapeutic targets.

Inflammatory indicators in tears and DR

The tear film consists of three layers: a protein layer, an aqueous layer, and a lipid layer, which provide functional, nutritional, and protective benefits to the ocular surface. The components in tear fluid are relatively unstable and may vary during sampling due to factors such as corneal irritation, reflex tearing, and the use of artificial tears [50]. Therefore, the tear collection and storage process must preserve sample integrity to ensure reliable and consistent results.

Diabetic patients often exhibit reduced corneal sensitivity along with changes in tear quantity and quality. Advanced DR patients develop dry eye syndrome related to neurotrophic dysfunction, which can lead to corneal ulcers or neurogenic ulcers that impair vision, along with increased inflammatory factor expression on the ocular surface. IL-17 promotes neutrophil infiltration and induces the synthesis and secretion of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and reactive oxygen species (ROS), leading to disruption, epithelial dysfunction, and apoptosis in the corneal epithelium [51]. IL-2, IL-4, and TNF in tears have been suggested as potential biomarkers [52]. IL-6 is involved in acute-phase inflammation, and its levels correlate with increased ocular surface chemotaxis and keratinization [53]. IFN-γ induces the loss of conjunctival cup cells, reducing lacrimal vesicle mucin production and promoting apoptosis, correlating with the severity of tear film dysfunction. This increases the risk of corneal ulceration and impairs visual quality [54].

Indicators of inflammation in the retina and DR

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) provides detailed images of retinal layers and measures their thickness. OCT is now widely used in clinical practice. In diabetes-related retinal neurodegeneration, OCT reveals thinning of the retinal ganglion cell and nerve fiber layers [54].

Immunohistochemistry has identified IL-8 in retinal endothelial and glial cells, indicating that IL-8 is primarily of retinal origin [3]. Subfoveal neuroretinal detachment (SND), hyperreflective subretinal (HRS) lesions, and fundus autofluorescence (FAF) indicate inflammatory responses on OCT. SND, imaged by spectral domain (SD)-OCT, has been shown to correlate with inflammatory factors in the vitreous and is considered a marker of retinal inflammation in DR patients [55]. Isolated HRS dots (<30 μm in diameter) are primarily located in the inner nuclear layer of the retina and may be associated with glial cell aggregation, indicating a focal inflammatory response in the retina [56]. FAF is primarily derived from lipofuscin in the Retinal Pigment Epithelium (RPE). In DR, local ocular inflammation and oxidative stress increase lipofuscin levels in the macula, leading to heightened FAF signaling in DME patients [57]. HRS, SND, and FAF levels were reduced following anti-VEGF or steroid intravitreal treatment in DME patients [45], suggesting that these may serve as inflammatory markers.

New Technologies and Emerging Directions

Multi-omics: Stage-specific pathways and candidate panels

Over the past five years, multi-omics has rapidly become a unifying approach to decipher the heterogeneity of inflammatory phenotypes and stage-specific differences in DR. At the proteomic level, large-scale plasma proteomics combined with machine learning has been used to identify reproducible risk protein clusters and pathway enrichment profiles. Studies in cohorts of tens of thousands of (pre)diabetic participants have built “risk–mechanism” proteomic maps, indicating that proteins related to inflammation, complement activation, and vascular permeability hold promise for DR characterization and prediction [58]. In the metabolomic/lipidomic domains, broad-coverage targeted lipidomics shows lipid “rewiring” signals—such as alterations in sphingolipids and oxylipin derivatives—emerging before NPDR, enabling discrimination between NDR and NPDR and yielding translational candidates for early detection and stage diagnosis [59]. Concurrently, multi-omics reviews and integrative analyses emphasize that coupling the transcriptome with the metabolome and lipidome can reveal cross-level networks linking hyperglycemia to inflammation and, subsequently, to microvascular injury, and can delineate stage-specific metabolic pathways (e.g., purine metabolism, sphingolipid pathways, redox homeostasis). This integrative strategy supports constructing dynamically weighted biomarker panels that adapt to disease stage and phenotype, rather than relying on a static checklist.

Machine learning and multi-marker panels: Combinations outperform single analytes; External validation and calibration

A single biomarker cannot capture the multi-pathway pathobiology of DR. Recent studies have applied machine-learning models—such as Random Forest, XGBoost, and explainable approaches (e.g., SHAP)—directly to plasma, clinical chemistry, and multi-omics features, yielding AUCs commonly in the 0.75–0.82 range [60]. More importantly, these models uncover nonlinear feature interactions (e.g., inflammation-related proteins and lipid subclasses and renal indices) that are invisible to univariable analyses. Across reports, external validation, calibration curves, and decision-curve analysis (DCA) are consistently emphasized as prerequisites for clinical translation, mitigating the risk of models that “perform well only on the training set.”

In addition, the gut microbiome–short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) axis has been incorporated into DR models. Machine learning can extract composite microbial/metabolic signatures that discriminate DR status, highlighting the relevance of an immune–metabolic–gut–retina axis and supporting its inclusion in multimodal panels [61]. Panel development should follow a four-step pathway: candidate generation, internal validation, external validation and assessment of clinical net benefit (DCA). Reports should include incremental AUC and reclassification metrics (NRI/IDI) over conventional clinical models, alongside health-economic evaluation. To enhance generalizability across populations and platforms, provide threshold ranges rather than single cut-points, and predefine procedures for harmonization and recalibration in new settings.

Extracellular vesicles (EVS) and miRNAs (miR-21/ MiR-146a): Stable, repeatable sampling

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) and microRNAs (miRNAs) have emerged as attractive systemic readouts of inflammation owing to their stability, storage tolerance, and suitability for repeated sampling. Recent work links miR-21 and miR-146a to endothelial function and the NF-κB inflammatory axis, supporting their role as cross-organ messengers and molecular indicators of disease activity in diabetes and its complications [62]. In ophthalmic contexts, EV/miRNA signatures show promise for DR diagnosis, risk stratification, and treatment-response monitoring (e.g., to anti-VEGF or intravitreal corticosteroids).

Translational hurdles remain, chiefly pre-analytical standardization (collection tube material, centrifugation workflow, freeze–thaw cycles) and platform harmonization across laboratories. For clinical pipelines, we recommend prioritizing serum/plasma matrices, establishing SOPs with inter-laboratory quality assessment, and reporting assay characteristics (CV, LoD/LoQ). Analytically, integrating EV/miRNA features with proteomic and lipidomic markers within multivariable models can improve robustness and interpretability, while enabling alignment with mechanistic pathways (endothelial activation, leukostasis, complement activity). This combined strategy positions EV/miRNA readouts as complementary, not standalone, components of multi-marker panels geared toward early detection, phenotypic differentiation, and longitudinal monitoring in DR.

Complement pathway and potential interventions (C3a/ C5a/ Mac)

There is compelling evidence that complement contributes to local immune dysregulation in DR. In the human vitreous, proliferative DR (PDR) is characterized by intraocular activation of C3, C5, and factor B, indicating engagement of the alternative pathway [63]. The anaphylatoxins C3a and C5a recruit immune cells and activate microglia, thereby amplifying inflammation and increasing vascular permeability; downstream assembly of the membrane attack complex (MAC) further perturbs barrier integrity [64]. Although complement inhibitors (e.g., C3/C5 blockade) have achieved clinical progress in other retinal degenerations, translation to DR remains at a mechanistic and exploratory stage.

A pragmatic route forward is biomarker-led stratification: integrate complement fragments (C3a/C5a/MAC) with inflammatory cytokines and permeability/adhesion readouts (e.g., IL-6/TNF-α, sICAM-1/sVCAM-1) into a multi-marker panel to identify a complement-high-activity phenotype. This phenotype can then be evaluated—first in observational cohorts and pilot interventional studies—for its association with leakage, capillary nonperfusion, and retreatment need, and for signals of causality (e.g., biomarker shifts alongside structural/functional improvement).

Evidence and positioning of anti-inflammatory/ Anti-TNF strategies

Corticosteroids (e.g., intravitreal implants) downregulate multiple inflammatory mediators and improve vascular permeability, making them one of the most practical options for an inflammation-dominant phenotype of DR [65]. Anti-VEGF therapy remains the cornerstone for permeability and angiogenesis; in patients with a high inflammatory load, sequential or combined corticosteroid–anti-VEGF regimens may be considered. Recent precision-medicine reviews advocate biomarker-guided monitoring—using aqueous/vitreous samples or systemic inflammatory panels—to track cytokine changes before and after treatment, thereby identifying steroid-responsive versus steroid-tolerant subgroups and informing dosing intervals [66].

Systemic anti-TNF therapy lacks consistent phase III evidence in DR to date. Nonetheless, local delivery and new anti-inflammatory pathways—including IL-6/IL-17 axis modulation, JAK–STAT inhibition, and complement blockade—warrant exploration under a biomarker-led framework. The key is panel-based patient selection (e.g., integrating cytokines, adhesion molecules, and complement fragments) and composite endpoints that couple visual function and OCT structural outcomes with changes in inflammatory panels. Such designs can enrich trials for the most plausible responders, increase signal-to-noise, and improve translational success, while clarifying where anti-inflammatory strategies add value beyond anti-VEGF monotherapy.

Summary and Outlook

Currently, there are no established biomarkers for the early diagnosis and prediction of overt DR. Diabetic patients and clinicians seek early prediction of complications to mitigate damage to the eyes and other systemic organs. Inflammation is a key driver of the onset and progression of DR, and single markers cannot capture its multi-pathway biology or phenotypic heterogeneity. Clinically, practice should transition from single-marker strategies to multi-marker panels integrated with imaging: (i) employ low-cost systemic indices—such as CRP, NLR,PLR, and SII/SIRI—for broad screening and baseline inflammatory profiling; (ii) add mechanistic layers with TNF-α/IL-6 and adhesion molecules sICAM-1/sVCAM-1/sE-selectin; and (iii) integrate OCT/OCTA readouts (e.g., HRS, SND) for phenotypic stratification and treatment monitoring. Advancing a scalable, integrated laboratory-panel–imaging workflow is essential for achieving early detection, accessibility, and precision treatment.

Author Contributions

Dong: contributed to the concept and wrote the paper.

Xie: designed the work and revised the manuscript.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

All data analyzed in this review are derived from studies cited in the article. No new datasets were generated.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

References

2. Duh EJ, Sun JK, Stitt AW. Diabetic retinopathy: current understanding, mechanisms, and treatment strategies. JCI insight. 2017 Jul 20;2(14):e93751.

3. Vujosevic S, Aldington SJ, Silva P, Hernández C, Scanlon P, Peto T, et al. Screening for diabetic retinopathy: new perspectives and challenges. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology. 2020 Apr 1;8(4):337–47.

4. Achigbu EO, Onyia OE, Oguego NC, Murphy A. Assessing the barriers and facilitators of access to diabetic retinopathy screening in sub-Saharan Africa: a literature review. Eye. 2024 Aug;38(11):2028–35.

5. Yapanis M, James S, Craig ME, O’Neal D, Ekinci EI. Complications of diabetes and metrics of glycemic management derived from continuous glucose monitoring. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2022 Jun 1;107(6):e2221–36.

6. Xing Y, Wu M, Liu H, Li P, Pang G, Zhao H, et al. Assessing the temporal within-day glycemic variability during hospitalization in patients with type 2 diabetes patients using continuous glucose monitoring: a retrospective observational study. Diabetology & Metabolic Syndrome. 2024 Mar 1;16(1):56.

7. Christou GA, Tselepis AD, Kiortsis DN. The metabolic role of retinol binding protein 4: an update. Hormone and Metabolic Research. 2012 Jan;44(01):6–14.

8. Forrester JV, Kuffova L, Delibegovic M. The role of inflammation in diabetic retinopathy. Frontiers in immunology. 2020 Nov 6;11:583687.

9. Torok Z, Peto T, Csosz E, Tukacs E, Molnar A, Maros-Szabo Z, et al. Tear fluid proteomics multimarkers for diabetic retinopathy screening. BMC ophthalmology. 2013 Aug 7;13(1):40.

10. Amorim M, Martins B, Caramelo F, Gonçalves C, Trindade G, Simão J, et al. Putative biomarkers in tears for diabetic retinopathy diagnosis. Frontiers in medicine. 2022 May 25;9:873483.

11. Pusparajah P, Lee LH, Abdul Kadir K. Molecular markers of diabetic retinopathy: potential screening tool of the future?. Frontiers in physiology. 2016 Jun 1;7:200.

12. Nuha AE, Rozalina GM, Grazia A. 2. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes: standards of care in diabetes-2025. Diabetes Care. 2025;48(Supplement_1):S27–49.

13. Antar SA, Ashour NA, Sharaky M, Khattab M, Ashour NA, Zaid RT, et al. Diabetes mellitus: Classification, mediators, and complications; A gate to identify potential targets for the development of new effective treatments. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2023 Dec 1;168:115734.

14. Sakini AS, Hamid AK, Alkhuzaie ZA, Al-Aish ST, Al-Zubaidi S, Tayem AA et al. Diabetic macular edema (DME): dissecting pathogenesis, prognostication, diagnostic modalities along with current and futuristic therapeutic insights. International Journal of Retina and Vitreous. 2024 Oct 28;10(1):83.

15. Damato EM, Angi M, Romano MR, Semeraro F, Costagliola C. Vitreous analysis in the management of uveitis. Mediators of inflammation. 2012;2012(1):863418.

16. Han W, Wei H, Kong W, Wang J, Yang L, Wu H. Association between retinol binding protein 4 and diabetic retinopathy among type 2 diabetic patients: a meta-analysis. Acta Diabetologica. 2020 Oct;57(10):1203–18.

17. Wang W, Lo AC. Diabetic retinopathy: pathophysiology and treatments. International journal of molecular sciences. 2018 Jun 20;19(6):1816.

18. Ramos H, Hernandez C, Simo R, Simo-Servat O. Inflammation: the link between neural and vascular impairment in the diabetic retina and therapeutic implications. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2023 May 15;24(10):8796.

19. Mengstie MA, Chekol Abebe E, Behaile Teklemariam A, Tilahun Mulu A, Agidew MM, Teshome Azezew M, Zewde EA, Agegnehu Teshome A. Endogenous advanced glycation end products in the pathogenesis of chronic diabetic complications. Frontiers in molecular biosciences. 2022 Sep 15;9:1002710.

20. Martins B, Pires M, Ambrósio AF, Girão H, Fernandes R. Contribution of extracellular vesicles for the pathogenesis of retinal diseases: shedding light on blood-retinal barrier dysfunction. Journal of biomedical science. 2024 May 10;31(1):48.

21. Zeng J, Wu M, Zhou Y, Zhu M, Liu X. Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) in ocular diseases: an update. Biomolecules. 2022 Oct 8;12(10):1440.

22. Yao X, Zhao Z, Zhang W, Liu R, Ni T, Cui B, et al. Specialized retinal endothelial cells modulate blood-retina barrier in diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes. 2024 Feb 1;73(2):225–36.

23. Qian HY, Wei XH, Huang JO. Inflammatory mechanisms in diabetic retinopathy: pathogenic roles and therapeutic perspectives. American Journal of Translational Research. 2025 Aug 15;17(8):6262.

24. Yue T, Shi Y, Luo S, Weng J, Wu Y, Zheng X. The role of inflammation in immune system of diabetic retinopathy: Molecular mechanisms, pathogenetic role and therapeutic implications. Frontiers in immunology. 2022 Dec 13;13:1055087.

25. Pusparajah P, Lee LH, Abdul Kadir K. Molecular markers of diabetic retinopathy: potential screening tool of the future?. Frontiers in physiology. 2016 Jun 1;7:200.

26. Mason RH, Minaker SA, Lahaie Luna G, Bapat P, Farahvash A, Garg A, et al. Changes in aqueous and vitreous inflammatory cytokine levels in proliferative diabetic retinopathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eye. 2022 Jun 7:1–51.

27. Yue T, Shi Y, Luo S, Weng J, Wu Y, Zheng X. The role of inflammation in immune system of diabetic retinopathy: Molecular mechanisms, pathogenetic role and therapeutic implications. Frontiers in immunology. 2022 Dec 13;13:1055087.

28. Hartnett ME, Fickweiler W, Adamis AP, Brownlee M, Das A, Duh EJ, et al. Rationale of basic and cellular mechanisms considered in updating the staging system for diabetic retinal disease. Ophthalmology Science. 2024 Sep 1;4(5):100521.

29. Fang Y, Wang B, Pang B, Zhou Z, Xing Y, Pang P, et al. Exploring the relations of NLR, hsCRP and MCP-1 with type 2 diabetic kidney disease: a cross-sectional study. Scientific Reports. 2024 Feb 8;14(1):3211.

30. Peng D, Wang J, Zhang R, Tang S, Jiang F, Chen M, et al. C-reactive protein genetic variant is associated with diabetic retinopathy in Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes. BMC Endocrine Disorders. 2015 Mar 2;15(1):8.

31. Song J, Chen S, Liu X, Duan H, Kong J, Li Z. Relationship between C-reactive protein level and diabetic retinopathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Plos one. 2015 Dec 4;10(12):e0144406.

32. Bhutia CU, Kaur P, Singh K, Kaur S. Evaluating peripheral blood inflammatory and metabolic biomarkers as predictors in diabetic retinopathy and diabetic macular edema. Indian Journal of Ophthalmology. 2023 Jun 1;71(6):2521–5.

33. Chen H, Zhang X, Liao N, Wen F. Increased levels of IL-6, sIL-6R, and sgp130 in the aqueous humor and serum of patients with diabetic retinopathy. Molecular vision. 2016 Aug 9;22:1005.

34. Kristanti RA, Bramantoro T, Soesilawati P, Hariyani N, Suryadinata A, Purwanto B, et al. Inflammatory cytokines affecting cardiovascular function: a scoping review. F1000Research. 2022 Sep 21;11:1078.

35. Siddiqui K, George TP, Mujammami M, Isnani A, Alfadda AA. The association of cell adhesion molecules and selectins (VCAM-1, ICAM-1, E-selectin, L-selectin, and P-selectin) with microvascular complications in patients with type 2 diabetes: A follow-up study. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2023 Feb 9;14:1072288.

36. Reddy SK, Devi V, Seetharaman AT, Shailaja S, Bhat KM, Gangaraju R, et al. Cell and molecular targeted therapies for diabetic retinopathy. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2024 Jun 14;15:1416668.

37. Rajab HA, Baker NL, Hunt KJ, Klein R, Cleary PA, Lachin J, et al. The predictive role of markers of Inflammation and endothelial dysfunction on the course of diabetic retinopathy in type 1 diabetes. Journal of Diabetes and its Complications. 2015 Jan 1;29(1):108–14.

38. Zhang F, Xia Y, Su J, Quan F, Zhou H, Li Q, et al. Neutrophil diversity and function in health and disease. Signal transduction and targeted therapy. 2024 Dec 6;9(1):343.

39. Gao Y, Lu RX, Tang Y, Yang XY, Meng H, Zhao CL, et al. Systemic immune-inflammation index, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio in patients with type 2 diabetes at different stages of diabetic retinopathy. International Journal of Ophthalmology. 2024 May 18;17(5):877.

40. Wang S, Pan X, Jia B, Chen S. Exploring the correlation between the systemic immune inflammation index (SII), systemic inflammatory response index (SIRI), and type 2 diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity. 2023 Dec 31:3827–36.

41. Mahajan VB, Skeie JM. Translational vitreous proteomics. PROTEOMICS–Clinical Applications. 2014 Apr;8(3-4):204–8.

42. Feng Y, Ye D, Wang Z, Pan H, Lu X, Wang M, et al. The role of interleukin-6 family members in cardiovascular diseases. Frontiers in cardiovascular medicine. 2022 Mar 23;9:818890.

43. Takeuchi M, Sato T, Tanaka A, Muraoka T, Taguchi M, Sakurai Y, et al. Elevated levels of cytokines associated with Th2 and Th17 cells in vitreous fluid of proliferative diabetic retinopathy patients. PloS one. 2015 Sep 9;10(9):e0137358.

44. Reddy SK, Devi V, Seetharaman AT, Shailaja S, Bhat KM, Gangaraju R, Upadhya D. Cell and molecular targeted therapies for diabetic retinopathy. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2024 Jun 14;15:1416668.

45. Vujosevic S, Simó R. Local and systemic inflammatory biomarkers of diabetic retinopathy: an integrative approach. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2017 May 1;58(6):BIO68–75.

46. Robert M, Miossec P, Hot A. The Th17 pathway in vascular inflammation: culprit or consort?. Frontiers in Immunology. 2022 Apr 11;13:888763.

47. Borgia F, Custurone P, Li Pomi F, Cordiano R, Alessandrello C, Gangemi S. IL-31: state of the art for an inflammation-oriented interleukin. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022 Jun 10;23(12):6507.

48. Ecker SM, Hines JC, Pfahler SM, Glaser BM. Aqueous cytokine and growth factor levels do not reliably reflect those levels found in the vitreous. Molecular vision. 2011 Nov 9;17:2856.

49. Zhang H, Liang L, Huang R, Wu P, He L. Comparison of inflammatory cytokines levels in the aqueous humor with diabetic retinopathy. International Ophthalmology. 2020 Oct;40(10):2763–9.

50. Tamhane M, Cabrera-Ghayouri S, Abelian G, Viswanath V. Review of biomarkers in ocular matrices: challenges and opportunities. Pharmaceutical research. 2019 Mar;36(3):40.

51. Liu R, Gao C, Chen H, Li Y, Jin Y, Qi H. Analysis of Th17-associated cytokines and clinical correlations in patients with dry eye disease. PloS one. 2017 Apr 5;12(4):e0173301.

52. Amorim M, Martins B, Caramelo F, Gonçalves C, Trindade G, Simão J, et al. Putative biomarkers in tears for diabetic retinopathy diagnosis. Frontiers in medicine. 2022 May 25;9:873483.

53. López-Contreras AK, Martínez-Ruiz MG, Olvera-Montaño C, Robles-Rivera RR, Arévalo-Simental DE, Castellanos-González JA, et al. Importance of the use of oxidative stress biomarkers and inflammatory profile in aqueous and vitreous humor in diabetic retinopathy. Antioxidants. 2020 Sep 20;9(9):891.

54. Jenkins AJ, Joglekar MV, Hardikar AA, Keech AC, O'Neal DN, Januszewski AS. Biomarkers in diabetic retinopathy. The review of diabetic studies: RDS. 2015 Aug 10;12(1–2):159.

55. Sonoda S, Sakamoto T, Yamashita T, Shirasawa M, Otsuka H, Sonoda Y. Retinal morphologic changes and concentrations of cytokines in eyes with diabetic macular edema. Retina. 2014 Apr 1;34(4):741–8.

56. Mat Nor MN, Guo CX, Green CR, Squirrell D, Acosta ML. Hyper‐reflective dots in optical coherence tomography imaging and inflammation markers in diabetic retinopathy. Journal of Anatomy. 2023 Oct;243(4):697–705.

57. Markan A, Agarwal A, Arora A, Bazgain K, Rana V, Gupta V. Novel imaging biomarkers in diabetic retinopathy and diabetic macular edema. Therapeutic Advances in Ophthalmology. 2020 Sep;12:2515841420950513.

58. Yang S, Xin Z, Xiong R, Zhu Z, Li H, Chen Y, et al. Proteome atlas for mechanistic discovery and risk prediction of diabetic retinopathy. Nature Communications. 2025 Oct 31;16(1):9636.

59. Sun W, Su M, Zhuang L, Ding Y, Zhang Q, Lyu D. Clinical serum lipidomic profiling revealed potential lipid biomarkers for early diabetic retinopathy. Scientific Reports. 2024 Jul 2;14(1):15148.

60. Zong GW, Wang WY, Zheng J, Zhang W, Luo WM, Fang ZZ, et al. A Metabolism‐Based Interpretable Machine Learning Prediction Model for Diabetic Retinopathy Risk: A Cross‐Sectional Study in Chinese Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Journal of Diabetes Research. 2023;2023(1):3990035.

61. Qin X, Sun J, Chen S, Xu Y, Lu L, Lu M, et al. Gut microbiota predict retinopathy in patients with diabetes: A longitudinal cohort study. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2024 Dec;108(1):497.

62. Duisenbek A, Avilés Pérez MD, Pérez M, Aguilar Benitez JM, Pereira Pérez VR, Gorts Ortega J, et al. Unveiling the Predictive Model for Macrovascular Complications in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: microRNAs Expression, Lipid Profile, and Oxidative Stress Markers. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2024 Nov 1;25(21):11763.

63. Dinice L, Cosimi P, Esposito G, Scarinci F, Cacciamani A, Cafiero C, et al. Oxidative Stress and Complement Activation in Aqueous Cells and Vitreous from Patient with Vitreoretinal Diseases: Comparison Between Diabetic ERM and PDR. Antioxidants. 2025 Jul 8;14(7):841.

64. Jiang F, Lei C, Chen Y, Zhou N, Zhang M. The complement system and diabetic retinopathy. Survey of Ophthalmology. 2024 Jul 1;69(4):575–84.

65. Vitiello L, Salerno G, Coppola A, De Pascale I, Abbinante G, Gagliardi V, et al. Switching to an intravitreal dexamethasone implant after intravitreal anti-VEGF therapy for diabetic macular edema: a review. Life. 2024 Jun 3;14(6):725.

66. Kaurich C, Mahajan N, Bhatwadekar AD. Precision Medicine for Diabetic Retinopathy: Integrating Genetics, Biomarkers, Lifestyle, and AI. Genes. 2025 Sep 16;16(9):1096.