Abstract

This article introduces and attempts to summarize some descriptive clinical-medical aspects of the autism condition. The purpose is to give a common knowledge base of what are pathological symptoms, characteristics of autism and secondary and related pathologies. In this picture, it will become clear that no symptom is single or isolated but the damage concerns a circuit, a higher function, a more complex system. Focusing on one aspect, one symptom and a single set of symptoms distracts from a general, overall picture. We have chosen not to unify them in order to also allow an articulated understanding of the characteristic, symptomatological, and psychological-emotional picture. We have chosen, methodologically, to describe, as and when possible, all these aspects in the words of autistic persons, leaving them to tell not so much the clinical symptom described from the outside, but how that symptom is experienced and described by the person.

Introduction

The aim of this article is to provide a common basis and an integrated synthesis of knowledge of the pathological symptoms, characteristics of autism and secondary and related pathologies.

In the overall picture we will describe, it will become clear that no single symptom is single or isolated, but that the damage concerns a circuit, a higher function, a more complex system. Once again, focusing on one aspect, one symptom and a single set of symptoms distracts from the overall and general picture.

We will talk about characteristics, referring to autistic isolation, thinking and imagination, attention disorders, the search for immutability and order, social development, relations with other people, relations with objects, communication, repetitive behavior, sleep disorders. We will talk about symptoms referring to verbal and non-verbal communication, social interaction, affectivity and sexuality, aggression, self-injury, imagination or repertoire of interests, the importance of order, obsessive-compulsive behavior. We will talk about sensory disorders referring to hearing, sight, smell, taste, touch, pain and other symptoms. Finally, we will discuss the emotional picture, referring to anxiety, fear, sadness and joy, distrust and mistrust, as well as anger and rage, and the autistic child's defenses against negative emotions. Finally, we will mention co-symptomatic conditions, a definition under which certain conditions of typical clinical pathology that are often associated and found concomitantly in persons diagnosed with autism are included.

Each of these descriptive blocks must be read in parallel and integrated with the others. It is clear that autistic isolation (in features) is related to social interaction (between symptoms) and the entire emotional picture. We have chosen not to unify them in order to also allow an articulated understanding of the characteristic, symptomatic and psychological emotional picture.

Characteristics

Symptoms generally begin to manifest slowly from the age of six months, becoming more explicit from the age of two or three years and continuing to increase into adulthood, although often in a less obvious form [1,2]. The autistic condition is distinguished not by a single symptom, but overall, by a triad of characteristic symptoms: deficits in social interaction, deficits in communication, and restricted and repetitive interests and behavior.

Other aspects, such as atypical eating, are also common, but are not essential for diagnosis. Individual symptoms of autism can be found in the general population, but for one to be able to speak of autism, it is necessary to distinguish the situation by severity [3,4].

Autistic isolation

Autistic closure or isolation, which is what gives the condition its name, is mainly implemented towards the outside world, in more severe cases this extreme defense can also be implemented towards a part of the stimuli that come from one's own mind or body.

This closure, which stems from the need to protect oneself from environmental stimuli that is too painful for one to be able to handle and endure, can be more or less severe and can therefore exclude other human beings but also animals and in the most severe cases objects from one's world.

People with symptoms of autism describe this closure using various symbolisms: Pier Carlo Morello [5] describes it as shutting oneself inside a glass dome, set above a frozen lagoon.

Temple Grandin [6], on the other hand, uses the simile of doors or glass panels inside which she felt trapped.

Donna Williams [7] describes autistic enclosure as the search for a state of mind full of light, color, and enchantment, in order to escape from the painful reality in which she lived, so as to find much-needed comfort.

This distancing and alienation from the reality that surrounds the child and losing oneself in an enchanted inner world can occur involuntarily and instinctively but can also be sought out through various stratagems. Donna Williams, for example, used colored dots in the air, wallpaper patterns, the repetition of certain noises.

Pier Carlo Morello, on the other hand, closed himself off from the outside world in his room and used fantasy and music.

People who are close to children or adults with symptoms of autism often try to bring them back to reality by using inappropriate ways such as scolding and reprimands, whereas it would be much more useful to be able to create an effective relationship, using the utmost gentleness and delicacy, for example by playing with them, without constraints or conditioning (free self-managed play) [8].

Thinking and ideation

The severe emotional disorders from which people with autism symptoms suffer, modify and alter not only their sensory abilities, but also their ideational abilities, generating confused and disorganized thoughts [9,10].

If these disorders are severe, these children or adults lose, at least in part, the ability to coherently order thoughts, ideas and sensations, resulting in difficulty, and in some cases inability to understand words, gestures and situations in everyday life [11].

Therefore, to observers, their behavior will appear strange, unusual or deficit.

Autistic people who have been able to describe their mental status speak of a confused and chaotic, threatening and frightening inner world: ‘Imagine a state of hyperactivation in which one is pursued by a dangerous aggressor in a world of total chaos’ [11].

An inner world in which one can have the distressing feeling of falling apart at any moment [12].

A world in which there is difficulty in understanding the logic behind things and events. A world that is completely incomprehensible, which prevents thought control over the activities one wants to carry out. All these psychological alterations are, among other things, easily detectable in their drawings and stories.

They try to remedy this confused and chaotic inner world by using a series of defenses: such as stereotyped behavior, precise rituals and routine behavior (Joliffe, cited by Grandin).

In other cases, in order to achieve a minimum of serenity and inner joy, these people use solitary games, such as working with numbers or constantly focusing their attention on certain, specific themes.

Fortunately, these psychic alterations, especially in children, are not stable, so much so that they can improve, until they disappear, when their inner world regains a good degree of serenity [13].

Attention disorders

Attention is the ability to focus one's thoughts on a particular subject or object and to maintain this focus for as long as necessary. Good attention skills also occur when one is able to divide one's attention between various objects or topics, without confining it to a single object or topic [14].

This capacity depends to a large extent on the frontal cortex, which is able to facilitate or block all the information concerning the task that, for that particular person, is prevalent at that moment [15].

Moreover, attention is closely linked to the physiological phenomenon of the wandering mind, which consists of shifting attention from the activity being performed to internal feelings, thoughts and personal concerns. This phenomenon characterizes 25% to 50% of our mind's activity during wakefulness [16]. Clearly, this involves being distracted from the task at hand. This occurs especially in times of stress and fatigue and manifests itself more in people who are sad, worried, anxious or depressed [17].

We find major attention disorders in people with autism symptoms who often fail to follow the thought or activity of the moment, on which they are drawn or would like to place their concentration, just as they fail to follow the thought and reasoning of others due to the constant presence of a variety of compelling internal emotions such as fear, distress, and suffering [13].

The search for immutability and orderliness

One of the many characteristics attributed to autistic children is the presence of a lack of flexibility in thinking and a remarkable resistance to change.

They experience a phobic terror when they are removed from their environment, if the location of objects or the appearance of rooms in their home is changed, or if the daily routine is altered.

Characteristic in these children is the ritualization of certain habitual daily activities, such as eating, washing, leaving the house. Activities that they need to take place according to rigid and possibly unchanging sequences [17].

They therefore do everything to ensure that situations, objects and schedules do not change and remain as they are. Says Grandin: ‘’Any alteration in routine causes panic attacks, anxiety and an escape response, unless the person is taught what to do when something goes wrong‘’.

The root cause of the need for immutability is certainly the anguish that pervades the mind, anguish that they continually try to combat and control, including by seeking immutability and order.

Since every change and shift in objects or normal routines accentuates the instability of their psyche and aggravates their anxieties and fears to such an extent that they can no longer effectively control the acute suffering they constantly experience [18].

However, autistic children, at other times or immediately after having sorted their toys absolutely perfectly, when they are left free to act and thus are not constrained by strict rules, like to ‘go wild’, throwing the same toys on the floor or in the air, thus creating moments of indescribable disorder.

For these particular children, it is much better to respect and follow their needs and their emotional needs of the moment, avoiding any pressure and forcing so that they feel the commitment of others not to neglect their needs and not to accentuate their discomfort.

Social development

Social deficits distinguish autism from other developmental disorders [19].

People diagnosed with autism present social difficulties and often do not have the same behaviors that many people take for granted. Temple Grandin explained that her inability to understand the social communication of neurotypicals, or people with normal neural development, makes her feel like ‘an anthropologist on Mars’ [20].

The unusual social development becomes evident in early childhood. Autistic children show less attention to social stimuli, smile and observe others less often and respond less frequently to their own name. They also differ more markedly with regard to social norms; for example, they look others in the eye less often and do not often use simple movements to express themselves, such as pointing at things [21].

Autistic children aged three to five are less likely to understand social dynamics, approach others spontaneously, imitate and respond to emotions, communicate non-verbally and take turns in a discussion [22].

Most autistic children show less secure attachment than neurotypical children, although this difference is not found in those with higher intellectual development or a less severe autistic condition [23].

Older children and adults with autism spectrum disorder perform worse on visual tests with regard to facial emotion recognition [24], although this may be partly due to a lower ability to define their own emotions [25].

High-functioning autistic children suffer from more intense and frequent loneliness than non-autistic peers, despite the common misconception that autistic children prefer to be alone.

Creating and nurturing friendships often proves to be difficult, but the quality of friendships, and not the number of friends, is more influential: functional friendships, such as those resulting from invitations to parties or social activities, may have a greater influence on quality of life [26].

There are many anecdotal reports, but few systematic studies concerning aggressive or violent attitudes on the part of persons with autism. Limited data indicate that, in children with mental retardation, autism may be correlated with aggression, harm and tantrums [27].

Relationships with other people

The relationships of children with autism symptoms with other people are remarkably difficult. Their considerable social and relational problems include typical behaviors such as evading dialogue and the gaze of others, not accepting but opposing requests made to them, not showing proper attention to others [9], not sharing the joys, interests and goals of loved ones, having a desire to be alone, not responding adequately to normal educational systems, and so on.

People diagnosed with autism routinely feel that the people they relate to are often unable to understand their inner world, their deepest and truest problems, the reasons for their oppositional attitudes, the true causes of their unusual symptoms, and the defenses they put up to manage, diminish or ward off the most distressing and painful emotions they suffer from.

Often the people with whom they communicate do not implement those behaviors and attitudes, desired by them, that can make the relationship effective and suitable to their needs.

Because they do not feel understood in their needs and desires, they perceive both children and adults who are within the norm as bringing problems, anxiety, suffering, and pain [28].

Therefore, as Donna Williams states, the relationships they have with other human beings are often marked by mistrust, distrust, suspicion, if not considerable fear, so much so that they dislike and sometimes have impatience with the objects that represent them: dolls and dollsettes, and they more readily accept cues from a tape recorder than from people [18].

With regard to relationships with other children, they often do not like to take part in the games of other children, so much so that they prefer to remain alone, since playing with peers is not pleasant and fun for them either because of the limitations they have or because of the difficulty they perceive in other children playing as they would like to [29].

The relationship with objects

The relationships that autistic persons have with objects are certainly better and more intense than those they have with human beings, with whom, on the other hand, they have considerable difficulty establishing strong and positive bonds [6].

This is because objects accept, without criticism, reprimand, punishment or protest, their need for order, their stereotypies, as well as their moments of aggression and destructiveness and all their other symptoms. Moreover, the objects accommodate their positive emotions as well as they are able to express them.

Towards some of these (pledge objects) they have a considerable attachment, so much so that they carry them with them at all times [18].

Williams, for example, was particularly attached to perfume and wool objects because of the warm and positive experience she had had as a child with her grandmother, who, over time, had shown her respect, affection and understanding.

Since these ‘pledge objects’ help them to cope better with anxieties, fears and moments of despondency, from which they suffer, giving them some joy and security, it is good not to deprive them or criticize them for their attachment to them.

Communication

Approximately one third to one half of autistic persons are unable to develop sufficiently natural language to meet their everyday communication needs [30].

Communication deficits can occur as early as the first year of life and may include delayed onset of lalication, unusual gestures, decreased responsiveness and unsynchronized speech patterns. In the second and third years, autistic children have less frequent and less diversified use of consonants, word combinations and lalla; their gestures are less frequently integrated with words. Children are less inclined to make requests or share experiences and are more likely to simply repeat the words of others (echolalia) or resort to pronoun inversion [31-33].

In some studies, high-functioning autistic children between the ages of 8 and 15 years performed as well as and better than adults on basic language checks involving vocabulary and spelling, both in pairs and individually. However, it was seen that the autistics performed worse on complex language tasks, such as figurative language, comprehension, and inference. These studies therefore suggested that people who communicate with autistic people are more likely to overestimate what their interlocutor perceives [36].

Repetitive behavior

Autistic persons display many forms of repetitive or restricted behavior, categorized as follows according to the Repetitive Behavior Scale-Revised (RBS-R) [37]:

- Stereotypy is a repetitive movement, such as hand flapping or head rocking.

- Compulsive behavior is expected and appears to follow rules, such as arranging objects in piles or lines.

- Monotony: is resistance to change; for example, insisting that furniture should not be moved.

- Ritualistic behavior involves an invariable pattern of daily activities, such as unchanging food and dressing rituals.

- Restricted behavior is focused on interests or activities, such as focusing on a single television program, a single toy or a particular game.

- Self-injury includes movements that may harm or injure people [36].

Williams recounts: ‘Terror invaded me. Carping on the floor, I cried like a child. I felt the cold and hardness of the tiles and stared at my hands stretched out towards them. I felt I could not breathe. I felt the fear of the unknown lurking somewhere in the room. I groaned, terrified, lost and helpless. I cowered, trembling with fear, and rocked like a child’. Visual and auditory hallucinations are also possible in this situation.

It is a cross-sectional observation that the efforts of parents and educators to make their child experience serene and joyful moments during the day, while at the same time avoiding any occasion of anxiety and stress, markedly improves the child's nights.

Symptomatology

The severity and symptomatology of autism vary greatly from individual to individual and tend in most cases to improve with age, particularly if mental retardation is mild or absent, if verbal language is present, and if valid therapeutic treatment is undertaken at an early age.

Autism can be associated with other disorders, but it should be emphasized that there are different degrees of autism. Some autistic persons possess, for example, an extraordinary capacity for mathematical calculation, musical sensitivity, an exceptional audio-visual memory or other talents to an extent quite out of the ordinary, such as the ability to produce very faithful portraits or landscapes on canvas without having any technical knowledge of drawing or painting.

Normally, the symptoms, which only at first glance may seem similar to the characteristics of introversion, actually manifest themselves as a true autistic withdrawal (in the sense of noticeably abnormal and not always comprehensible behavior, due to which the person is exposed to a high risk of social isolation), due to severe alterations in functional areas.

Verbal and non-verbal communication

‘’Many children with autism, a percentage varying between 20% and 50%, do not acquire any verbal language. Another 25% acquire some words between 12 and 18 months and then go through a regression associated with the loss of verbal language‘’ [29].

Autistic persons who are able to use language express themselves on many occasions in a bizarre way, often repeating words, sounds or sentences they have heard spoken.

Echolalia can be immediate (repetition of words or phrases immediately after hearing) [37] or deferred (repetition of previously heard phrases or words at a distance of time) [37].

Alongside echolalia, verbal stereotypies (the child repeats words or phrases unrelated to the situation and experiences of the moment) are often present.

Some children with autism invent new words (neo language) [38].

There may also be a disturbance in the melody of speech that may appear sing-songy or excessively mannered.

Even if imitative abilities are intact, these individuals often have considerable difficulty in applying the new learnings constructively to situations other than those that generated them in the first instance.

Therefore: ‘’Communicating with a person with autistic disorder may be difficult or impossible for different and seemingly opposite reasons. At the two extremes of the continuum there are on the one hand subjects who have never acquired language and do not respond and do not initiate any communicative exchange, and on the other hand subjects who continuously initiate conversations using a rich and formally appropriate vocabulary, but who are not able to flexibly adapt their communication to the interactive context, to maintain reciprocity and alternating turns in the communicative exchange and to correctly interpret all the communicative exchanges expressed by the interlocutor‘’ [29].

It must be borne in mind that both verbal and non-verbal communication develops correctly when certain precise conditions are present: desire and pleasure in the exchange with the other and attention to the external world, sufficient inner serenity, normal sensory capacities, and adequate age.

In the autistic child, unfortunately, some and sometimes all of these conditions are missing.

Having no trust in the outside world, these children have no desire to communicate but mainly feel the need to defend themselves against others. As their inner world is greatly disturbed by anxieties, fears, and considerable restlessness, there is not the minimum of inner serenity that can enable them to hear, and process sounds and thoughts correctly. Moreover, although children with autistic disorders hear perfectly well, the reaction to certain sounds produces alarm in them. They therefore try to defend themselves against this frustrating situation by alienating themselves from the outside world as much as possible.

However, when the child succeeds in acquiring a better inner serenity and greater trust in others and in himself, both verbal and gestural communication improve markedly; when this improvement occurs before the age of five to six, an age at which the speech centers are still well active. Unfortunately, when the child exceeds this age, the greatest acquisitions are mainly in the area of gestural communication.

Social interaction

Autistic persons show an apparent lack of interest and relational reciprocity with others, a tendency towards isolation and social closure, apparent emotional indifference to stimuli or, on the contrary, hyperexcitability to them, and difficulty in making direct eye contact: the autistic child who continues to avoid the gaze of others around the age of two years shows, according to various studies, a greater social disability in the future [39].

Autistic persons have difficulty initiating a conversation or respecting their ‘turns’, as well as difficulties in answering questions and participating in group life or games. It is not uncommon for children with autism to be initially checked for suspected deafness, as they show no apparent reaction (just as if they had hearing problems) when called by name.

Affectivity and sexuality

When autism is not excessively severe, affective feelings towards those who understand, help and can relate well to children, adolescents and adults diagnosed with autism are by no means the exception. They are capable of loving and bonding, showing clear signs of friendship towards those who care for them and manage to respect their needs, difficulties and problems [13].

Similarly, adolescents and adults, with non-severe symptoms of autism, are also able to experience intense loving feelings towards the opposite sex. Just as they have sexual thoughts and desires, to the extent of practicing masturbation [5,11].

In spite of this, we cannot deny the difficulties they experience when they would like to establish, and then maintain, an affective, loving and sexual relationship that is also lasting, pleasurable and gratifying. These difficulties are present both when their interests are directed towards people who fall within the norm, and when they try to establish a loving relationship with adolescents and adults who present symptoms of autism. And this causes them disappointment and frustration [5,7].

These difficulties are due to the complexity present in every stable and lasting love relationship. In this type of relationship, communication skills, psychological and emotional well-being, dialogue and acceptance skills, the correct management of physical contacts, and the ability to harmonize one's needs with those of the other are indispensable. And if this is arduous for people who fall within the neuronormal range, it is much more so for adolescents and adults with autism because of the difficulties they present, both in the relational and communicative spheres, and due to the presence of emotional disorders: anxieties, fears, and insecurities [7].

Before helping them to enter into emotional bonds, it is therefore necessary to work to diminish, and if possible, resolve psychological problems, so that these experiences, of fundamental importance for every human being, are not only possible but also enjoyable and gratifying.

Aggressiveness

If aggression frequently arises as a response to suffering endured, it is no wonder that aggressive behavior is present in the autistic child or young person, who is immersed in a state of emotional dysregulation [9], with a continuous state of anxiety and fear towards a world that they perceive as hostile and threatening. And because the subjective element is important in aggressive reactions, whereby the reaction depends on the personality characteristics of the subject and their experiences at the time, these reactive behaviors can also be present without clear and immediate provocation [40].

However, aggressive feelings are not always manifested. In the most severe cases, these are as if frozen and sterilized, to prevent destructive reactions from the surrounding world [7].

Typically, aggressive manifestations are directed towards objects that are slammed on the ground or walls, torn or destroyed or towards people whose behavior does not respect their needs for serenity, tranquility and their fear of being approached or touched [7].

Self-harm

One of the symptoms that is most disconcerting and upsetting to family members and caregivers caring for any child or young person diagnosed with autism is self-harm. It is certainly traumatic to witness one's own child or pupil hurting themselves: banging their head on the wall or on some piece of furniture, biting their arms or their tongue, slapping or scratching and injuring themselves with their nails or with some sharp or pointed object. The causes of self-injury may be different and may coexist in the same person.

While sometimes these behaviors arise from the fear of turning aggression outwards, so as not to suffer the destructive consequences of their thoughts or behavior towards others [7], in other cases it may also be a means of challenging those who, through behavior that does not match their needs and feelings, have provoked their anxiety and fears [18].

Self-aggressiveness may also manifest itself as guilt for having done, said or thought something that should not have been said, said or done, towards a person who had been good and kind [7].

Or it may simply be a way of feeling something, in the vacuum of the autistic condition: one's body, one's emotions, oneself, using a painful feeling [7].

Finally, self-aggression can be an extreme and desperate act, when they notice that those around them have no care and attention towards their suffering, their fears, their needs.

Fortunately, when parents and caregivers respect their needs for non-interference and their continuous search for moments of tranquility and peace, both hetero-aggressiveness and self-aggressiveness diminish until they cease altogether. Just as they diminish and cease when they accept that aggressive feelings can be vented on objects or through non-injurious games played with adults [13].

Imagination or repertoire of interests

Usually, a limited repertoire of behaviors is repeated obsessively; stereotypical postures and sequences of movements (e.g. twisting or biting hands, waving them in the air, rocking, making complex head movements, etc.) known as stereotypies can be observed.

Autistic persons may show excessive interest in objects or parts of objects, particularly if they have round shapes or can rotate (oval balls, marbles, spinning tops, propellers, etc).

Sometimes the autistic person tends to abstract himself from reality and isolate himself in a sort of ‘virtual world’, in which he feels he is living for all intents and purposes (sometimes conversing with invented characters).

Although in many cases they maintain awareness of their fantasizing, it is with difficulty and only with external stimuli (sudden sounds, calls from other people) that they manage to participate to varying degrees in group life.

Importance of order

In some autistic persons there is a marked resistance to change, which for some can take on the characteristics of a true phobic terror. This may occur if the person is removed from his or her environment, or if the location of objects, furniture or otherwise the appearance of the room is inadvertently changed.

The same may occur if objects are left in disorder (chairs moved, windows opened, newspapers in disarray): the autistic person's spontaneous reaction will be to immediately restore things to their order or, if unable to do so, to manifest restlessness anyway. The person may then explode into fits of crying or laughter, or even become self-destructive and aggressive towards others or objects. Others, on the contrary, show excessive passivity, motor apraxia and hypotonia, which seems to make them impervious to any stimulus [41].

Sensory Disorders

Sensory disturbances are very frequent in people with autism symptoms. Sometimes they occur with an increased sensitivity to stimuli from the outside world, but also from one's own body (sensory over-response) while, in other cases, at other times or due to other sensations, they may manifest themselves with a decreased sensory response (sensory hypo-response).

Altered interpretations coming from the senses are also very common. In these cases, even a trivial stimulus can be interpreted as something aggressive or damaging, resulting in fear, anxiety, if not outright panic attacks.

Thus, there can sometimes be an excessive and abnormal search for particular stimuli or, on the contrary, a clear rejection of, and therefore, a distancing from specific sensory experiences [9].

The consequences of these altered perceptions are reflected in behavior, e.g. in the ability to relate to and socialize with other peers, but also in their learning abilities [11,42].

These sensory alterations, caused by the severe psychological disorder of these people, tend to worsen their already greatly disturbed inner world, making them even more anxious, unstable, irritable, and confused.

Hearing

As far as hearing is concerned, people with autism symptoms, due to their irritability, fragility and altered inner reality, manifest, more frequently and with more emotional involvement, fears and phobias, resulting in nervous breakdowns or escapes, due to numerous types of sounds such as loud noises, ambulance sirens, loud music, bangs, shouting and hubbub present at parties or in classrooms, the echo that is created in gyms and school toilets, and so on [5,6].

It is important what meaning a particular sound or noise takes on in their minds. Thus, the same noise may be perceived as pleasant by one person while it may terrify another.

In other cases, and in other children, it is as if a deaf condition is present, as they do not respond in any way and are absolutely indifferent to even loud and persistent sounds, when they are immersed and estranged in their magical world, to the extent that they exclude the world outside of them. On the other hand, the same children may become agitated and disturbed by a soft, gentle sound. This suggests that there is no specific anatomical alteration of the receptors that amplifies or reduces the sounds heard, but that the way in which these people, in a certain psychic situation, experience, interpret and perceive certain sounds or noises is fundamental.

Taste

Also, with regard to taste, people diagnosed with autism are generally very selective and picky, so they generally do not like to taste foods that are crunchy, jelly-like, too hot, too cold.

Like many young or psychologically disturbed children, they tend to associate favorite foods with pleasant and pleasant people, animals and situations, while, conversely, they reject foods that they associate with unpleasant or unpleasant people, animals, and situations [7].

Touch

Touch is related to very intimate and primitive sensations.

Autistic children, who are affectively and psychologically very immature and disturbed, experience these feelings in particular ways, so they are often afraid of being touched and hugged not only by strangers but also by their parents [7,11] to the extent that they react aggressively towards those who do not respect their needs and fears.

However, if they hate some types of contact, they may love other, strange and unusual types of contact, such as touching curtains, furniture and other peculiar objects, such as the stringer (also known as the ‘hugging machine’) [6].

Also in this area, there are no consistent characteristics, whereby other children diagnosed with autism desire and love to be touched by their parents and also by strangers [11].

Pain

Even for painful sensations there can be considerable differences, whereby some children with autistic disorders will not tolerate and cry out over a small scratch, while others, or the same ones, at other times and on other occasions, may not mind very intense painful sensations (sensory anesthesia), either when the pain is caused by themselves (self-injury), or when it is caused by others [7].

Ultimately, all sensory input is felt according to their age, their specific psychological characteristics, their experiences and their inner experiences at the time.

Other symptoms

Autistic persons may present certain symptoms that are independent of the diagnosis, but that may influence their life or family sphere, and that may interact and infer with other typical characteristics [3].

It is estimated that approximately 0.5 to 10 per cent manifest unusual abilities, ranging from great capacity in specific tasks, such as an extraordinary ability to memorize irrelevant details, to the development of conditions known as ‘savant syndrome’ [43]. Many people with autism spectrum disorder show superior abilities to the general population in perception and attention [44].

Sensory abnormalities are found in over 90% of cases [45] although there is no evidence that sensory symptoms differentiate autism from other developmental disorders [46,47].

It is estimated that approximately 60 to 80 per cent of people diagnosed with autism have motor signs that include poor muscle tone, apraxia, and predominantly toe walking.

Deficits in motor coordination are widespread [48].

In approximately three quarters of autistic children, unusual eating behavior is found. Selectivity is the most common problem in which both ritual eating and refusal of food can occur [49].

This does not appear to cause episodes of malnutrition. Although some children with autism experience gastrointestinal symptoms, there is no adequate quantitative analysis of published rigorous data to support that this occurs more than the average for peers [50,51].

The Emotions of the Autistic Child

Many prejudices accompany the autistic syndrome.

One of the most widespread is that these children do not feel or only modestly feel emotions. This is absolutely untrue, and would, moreover, be incompatible with the findings of high levels of anxiety, numerous distressing fears, often combined with manifestations of anger and rage.

The presence of an emotionally highly disturbed inner world is already evident from the stories and drawings that these children sometimes manage to construct. Tales and drawings in which distressing, gory, gruesome, or coprolocal themes predominate.

Temple Grandin describes her emotions as follows: ‘Some people believe that people with autism have no emotions. I do have them, but they are more like the emotions of a child than those of an adult' [6].

Anxiety

As far as anxiety is concerned, this emotion, in the mild forms of autism, expresses itself above all with symptoms such as lability of attention, hyperactivity, hyperkinesis, and considerable reactivity even to small frustrations.

In these forms, when the child wishes to make friends with peers, anxiety and inner excitement severely impair his relational abilities, so that, in relationships with peers, because the child lacks the serenity necessary to listen to others, accepting their needs and desires, he is often rejected and rejected.

In severe forms of autism, although the anxiety is masked by more severe symptoms such as stereotypies, apparent apathy and indifference, it can easily be seen in the unpredictable, sudden and frequent mood swings and acute crises of anguish, provoked by minimal frustrations. Moreover, in many cases, this distressing emotion manages to disrupt the structural organization of thought with alterations in language that can become disconnected and incoherent.

Fears

When the child is confronted with particular situations, objects and tactile, visual or auditory stimuli, or when faced with slight changes in the world around him, fears can also manifest themselves dramatically, with screams and disheveled attitudes.

Temple Grandin describes her fears as follows: ‘The problems of such a person are further complicated by a nervous system that is often in a state of heightened fear and panic. Since fear was my main emotion, it spilled over into all events that had any emotional significance'. ‘Since puberty I had experienced constant fears and anxieties, accompanied by strong panic attacks, occurring at varying intervals from a few weeks to several months. My life was based on avoiding situations that could trigger a panic attack. With puberty, fear became my main emotion' [6].

Sadness and joy

It is not always possible to highlight these two emotions because sometimes, and in some children, they present themselves in an excessive and abnormal way, while in others or at other times they are not always evident, as they are masked by non-congruent facial expressions [17]. Thus, a facial expression that is always the same or attitudes with displays of excessive and foul-mouthed laughter may conceal great sadness and distress or, on the contrary, moments of true serenity and joy.

Nevertheless, when adults, be they parents, teachers or caregivers, manage to listen to the child's deepest emotions, without being distracted by his or her more superficial or extreme behavior and emotional manifestations, it is not so difficult to grasp his or her true emotions so as to behave accordingly.

Distrust

The inner world of children diagnosed with autism is not only greatly disturbed by anxiety, sadness, phobias, and fears and an abnormal state of arousal, but it is also altered due to the considerable distrust and mistrust of the world around them, which is frequently perceived as bad, treacherous, inconsistent and bringing constant anguish and frustration. Therefore, they often find themselves alone in an environment in which they do not feel understood and accepted, and this increasingly leads them to closure.

The autistic child's defenses against negative emotions

From what has been said, it is easy to understand that a large part of the symptoms can be traced back to defenses, often archaic and therefore not very functional, that children put in place to avoid, alleviate or overcome their suffering, caused by intense negative emotions such as anxiety, fear, depression and considerable distrust of others and themselves.

Autistic children, for example, try in every way to avoid, through closure, people, places, objects and situations in which they are uncomfortable, or which may accentuate their discomfort. Since every change accentuates their anxieties and fears, they have an aversion to every new experience, whether it be a new food, a different object, place or time. To diminish their sadness, they sometimes resort to nervous laughter, since by laughing their sadness and anxiety are diminished, while, at the same time, this mimic expression not only does not offend or hurt anyone, but is frequently accepted by others, as it is mistaken for an expression of joy.

Another way to diminish anxiety and inner malaise is to implement repetitive behavior, such as stereotypies. Self-harm can also be used to decrease confusion and reduce inner tension, as the pain that is provoked serves to distract them for a few moments from distressing experiences, while simultaneously allowing them to be more present [52].

Co-symptomatic and Co-pathological Conditions

In this definition, we discuss typical clinical pathology conditions that are associated with co-occurring symptoms in persons diagnosed with autism.

While this is a statistical list, which does not necessarily have an ecological correlation, in some cases it is almost the consequent pathological effects of the other biological alterations.

Abnormal folate metabolism

There is a variety of evidence of abnormalities in folate metabolism. These abnormalities can lead to decreased production of 5-methyltetrahydrofolate, alter the production of folate metabolites and reduce the transport of folate across the blood-brain barrier to neurons. The most significant abnormalities of folate metabolism associated with autism spectrum disorders may be autoantibodies against the folate receptor alpha (FRα). These autoantibodies have been associated with brain folate deficiency. Autoantibodies can bind to FRα and significantly impair its function.

Moreover, significant improvements in the general clinical picture have been noted in autistic children with brain folate deficiency when they take folinic acid.

In a series of five children with cerebral folate deficiency and low-functioning autism with neurological deficits, an overall reduction in typical symptoms was found with folinic acid use in one child and substantial improvements in communication in two others [53].

Abnormal redox metabolism

An imbalance in glutathione-dependent redox metabolism has been shown to be associated with autism spectrum disorders. Glutathione synthesis and intracellular redox balance are related to folate metabolism and methylation, metabolic pathways that have been shown to be abnormal in persons diagnosed with autism. Together, these metabolic abnormalities define a distinct endophenotype of TSA that is closely associated with genetic, epigenetic and mitochondrial abnormalities, as well as autism-related environmental factors. Glutathione is involved in neuroprotection against oxidative stress and neuroinflammation by enhancing the antioxidant stress system.

Interestingly, recent studies have shown that N-acetyl-1-cysteine, a glutathione precursor supplement, is effective in improving symptoms and behavior associated with autism [54].

However, glutathione was not measured in these studies.

Small, medium and large open DPBC studies and clinical trials show that new treatments for children with autism spectrum disorders for oxidative stress are associated with improvements in baseline symptoms, sleep, gastrointestinal symptoms, hyperactivity, seizures and parental impressions, sensory disturbances, and motor symptoms. These new treatments include N-acetyl-l-cysteine, methylcobalamin with and without oral folinic acid, vitamin C and a vitamin and mineral supplement including antioxidants, Q10 enzyme, and B vitamins.

Several other treatments that have antioxidant properties, including carnosine, have been reported to significantly improve behaviors associated with autism spectrum disorders, suggesting that treatment of oxidative stress may be beneficial.

Many antioxidants may also help improve mitochondrial function, suggesting that clinical improvements with antioxidants could occur through reduced oxidative stress and/or improved mitochondrial function [55].

Intestinal pathology

Gastrointestinal symptoms are a common co-symptom in people with autism spectrum disorders, although the underlying mechanisms are largely unknown. The most common gastrointestinal symptoms reported by a proprietary tool developed and administered by Mayer et al. [56] are abdominal pain, constipation, diarrhea, and bloating, reported in at least 25% of participants.

Carbohydrate digestion and transport are impaired in autistic persons and are thought to be attributed to functional disorders that cause increased intestinal permeability, a deficiency in disaccharide enzyme activity, a secretin-induced increase in pancreatico-biliary secretion and an abnormal fecal flora of Clostridia taxa [57].

Developmental coordination disorder (dyspraxia)

Early accounts of Asperger's syndrome and other diagnostic schemes [58] include descriptions of developmental coordination disorder. Children diagnosed with autism may have a delay in the acquisition of motor skills requiring dexterity, such as riding a bicycle or opening a can, and may appear clumsy. They may be poorly co-ordinated, have an awkward or bouncy gait or posture, poor handwriting, other hand/dexterity disorders or problems with visual-motor integration, visual-perceptual skills, and conceptual learning [59].

They may show problems with proprioception (sensation of body position) with disturbance of co-ordination, balance, tandem gait, and finger-thumb apposition [60].

Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder

Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder or FASD is a common disorder that can mimic signs of autism [61].

Although study results are conflicting, it is estimated that 2.6 per cent of children with FASD also have an autism spectrum disorder, a rate almost twice as high as that reported in the general US population [62].

Fragile X syndrome

Fragile X syndrome is the most commonly inherited form of intellectual disability. It was named so because part of the X chromosome has a ‘defective piece’ that appears squashed and fragile when observed under a microscope. Fragile X syndrome affects about 2-5% of people diagnosed with autism [63].

If a child has Fragile X, there is a 50% chance that children born to the same parents will have Fragile X.

Hypermobility spectrum disorder and Ehlers-Danlos syndromes

Studies have confirmed a link between inherited connective tissue disorders such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS) and hypermobility spectrum disorder (HSD) with autism, as comorbidity and co-occurrence within the same families [64,65].

Mitochondrial diseases

The central actor in bioenergetics is the mitochondrion. Mitochondria produce approximately 90% of cellular energy, regulate the cellular redox state, produce ROS, maintain Ca2+ homeostasis, synthesize and degrade high-energy biochemical intermediates and regulate cell death through activation of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mtPTP). When they do not function or function poorly, less and less energy is generated within the cell. Damage and even cell death follow. If this process is repeated, entire organ systems begin to fail.

Mitochondrial diseases are a heterogeneous group of disorders that can affect several organs with varying severity. Symptoms may be acute or chronic with intermittent decompensation. Neurological manifestations include encephalopathy, stroke, cognitive regression, seizures, heart disease (cardiac conduction defects, hypertensive heart disease, cardiomyopathy, etc...) [66,67] diabetes, vision and hearing loss, organ failure, neuropathic pain and peripheral neuropathy.

Prevalence estimates of disease and mitochondrial dysfunction in studies range from about 5 to 80 per cent. This could be, in part, due to the unclear distinction between disease and mitochondrial dysfunction. The studies showing the highest rates of mitochondrial diagnosis are usually the most recent.

Some drugs are toxic to mitochondria

They can trigger or aggravate mitochondrial dysfunction or disease.

Anti-epileptics: Valproic acid (also used in various other indications) and phenytoin are the most toxic. Phenobarbital, carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, ethosuximide, zonisamide, topiramate, gabapentin, and vigabatrin are also included [68,69].

Corticosteroids (such as cortisone), isotretinoin (Accutane) and other vitamin A derivatives, barbiturates, some antibiotics, propofol, volatile anesthetics, non-depolarizing muscle relaxants, some local anesthetics, statins, fibrates, glitazones, beta-blockers, biguanides, amiodarone, some chemotherapeutics, some neuroleptics, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, and various other drugs [70,71].

Neuroinflammation and immune disorders

The role of the immune system and neuroinflammation in the development of autism is controversial. Until recently, there was little evidence to support the immune hypothesis, but research on the role of the immune response and neuroinflammation may have important clinical and therapeutic implications. The exact role of the heightened immune response in the central nervous system in people diagnosed with autism is uncertain, but it may be a primary factor in triggering and sustaining many of the comorbid conditions associated with autism. Recent studies indicate the presence of increased neuroimmune activity in both brain tissue and cerebrospinal fluid of people diagnosed with autism, supporting the hypothesis that a heightened immune response may be a key factor in the onset of autistic symptoms [72].

A 2013 review also found evidence of microglial activation and increased cytokine production in postmortem brain samples from people with autism [73].

Reduced NMDA receptor function

Reduced NMDA receptor function has been linked to reduced social interactions, locomotor hyperactivity, self-injury, prepulse inhibition (PPI) deficits, and sensory hypersensitivity. Findings suggest that NMDA dysregulation may contribute to core symptoms of autism spectrum disorders [74].

Strabismus

According to several studies, there is a high prevalence of strabismus in people diagnosed with autism with rates 3 to 10 times higher than in the general population [75].

Tinnitus

According to one study, 35% of autistic people are affected by tinnitus, a much higher percentage than the general population [76].

Tourette syndrome

The prevalence of Tourette syndrome among autistic people is estimated to be 6.5%, higher than the prevalence of 2%-3% in the general population. Several hypotheses have been put forward for this association, including common genetic factors and abnormalities in dopamine, glutamate, or serotonin [77].

Tuberous sclerosis

Tuberous sclerosis is a rare genetic disorder that causes benign tumors to grow in the brain and other vital organs. It has a consistently strong association with the autism spectrum. 1% to 4% of autistic people also have tuberous sclerosis [78].

Studies have reported that between 25% and 61% of people with tuberous sclerosis meet diagnostic criteria for autism with an even higher percentage showing features of a broader pervasive developmental disorder [79].

Vitamin deficiencies

Vitamin deficiencies are more common in autism spectrum disorders than in the general population.

Vitamin D: In a German study, vitamin D deficiency affected 78% of the hospitalized autistic population. 52% of the entire study group were severely deficient, a much higher rate than the general population. Other studies also show a higher rate of vitamin D deficiency [80].

Vitamin B12: Researchers found that overall, vitamin B12 levels in the brain tissue of autistic children were three times lower than in the brain tissue of children without a diagnosis of autism. This lower-than-normal vitamin B12 profile persisted throughout life in the brain tissues of patients with autism. These deficiencies were not visible by conventional blood sampling [81].

As for the classic vitamin B12 deficiency, it would affect up to 40% of the population, its prevalence has not yet been studied in autism spectrum disorders. Vitamin B12 deficiency is one of the most serious.

Vitamin B9 (folic acid): Studies have been conducted on folic acid supplementation in autistic children. "The results showed that folic acid supplementation significantly improved some symptoms such as sociability, verbal/preverbal cognitive language, receptive language, emotional expression and communication. In addition, this treatment improved the concentrations of folic acid, homocysteine and redox metabolism of glutathione standardized." [82,83].

Vitamin A: Vitamin A can induce mitochondrial dysfunction. According to a non-autism-specific study, "Vitamin A and its derivatives, retinoids, are micronutrients required in the human diet to maintain several cellular functions of human development in adulthood as well as during aging (...) Although an essential micronutrient, vitamin A has several toxic effects on the redox environment and mitochondrial function. The exact mechanism by which vitamin A causes its deleterious effects is not yet clear (...) Vitamin A and its derivatives, retinoids, disrupt mitochondrial function by a mechanism that is not fully understood." [71].

Zinc: The incidence rates of zinc deficiency in children aged 0–3, 4–9, and 10–15 years were estimated at 43.5%, 28.1%, and 3.3% for boys and 52.5%, 28.7%, and 3.5% for girls [84].

Magnesium: The incidence rates of magnesium deficiency in children aged 0–3, 4–9, and 10–15 years were estimated at 27%, 17.1%, and 4.2% for boys and 22.9%, 12.7%, and 4.3% for girls.

Calcium: The incidence rates of calcium deficiency in children aged 0–3, 4–9, and 10–15 years were estimated at 10.4%, 6.1%, and 0.4% for boys and 3.4%, 1.7%, and 0.9% for girls.

Inappropriate special diets for children diagnosed with autism have been found to commonly result in excess amounts of certain nutrients and persistent vitamin deficiencies [85].

We often focus on a specific trait or category of typical autism traits.

What we have briefly (and certainly not exhaustively) tried to represent is a general picture of the symptomatology and the overall characteristic picture.

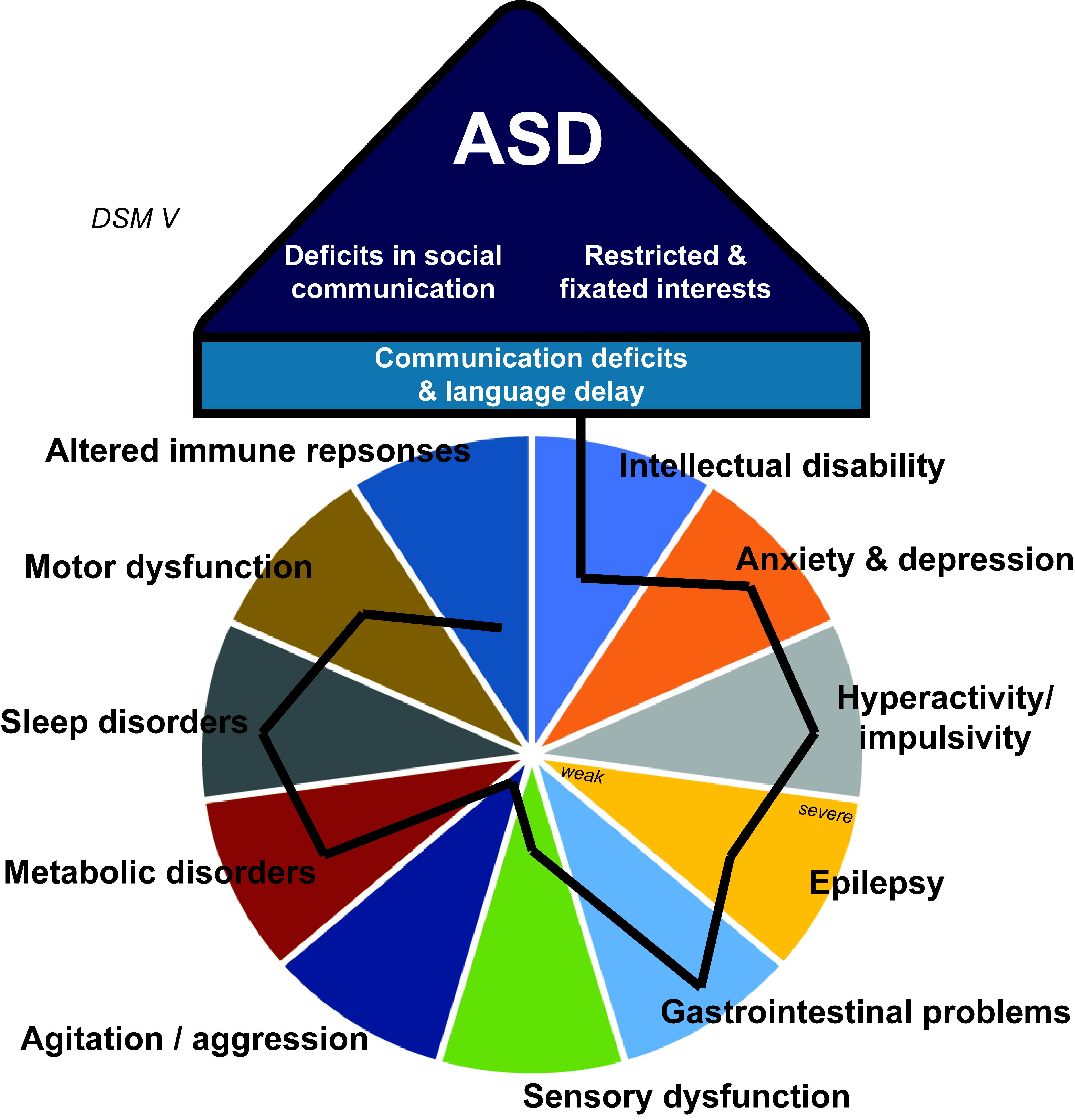

Figure 1. Clinical features of ASD. The three core features of ASD are deficits in social communication, restricted and fixated interests together with speech deficits, and language delays. The first two features are used to diagnose ASD according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition. In addition, individuals with ASD may present further symptoms and comorbidities such as cognitive deficits (intellectual disability), anxiety, depression, attention deficits and hyperactivity, impulsivity, seizures, gastrointestinal problems, sensory dysfunction, aggression, metabolic disorders, sleep disorders, motor dysfunction, and altered immune responses. However, not all symptoms and comorbidities are present in individuals with ASD, and those that are, vary in severity. This results in considerable heterogeneity of clinical features of individuals with ASD. The image is courtesy of Andreas Grabrucker, who processed it, and originally published in [86].

Through this schematic synthesis, a physical and psychological picture clearly emerges that has clear origins in the phases of neurological development, and not at the level of specific localization, but in the circuital and intra-circuital dynamics.

However, not all the characteristics and symptoms described must necessarily be traced back to a general diagnosis of autism. It is always possible that one or more characteristics are due to different etiologies, and only by chance is it found in the same person.

This brings us back to the centrality of an absolutely personalized and individualized diagnosis, which takes into account all the factors and moments of development, and which is not limited to adding in a necessarily unitary frame of reference characteristics that can be coincidentally correlated.

This breakdown of the picture into a more articulated and differential analysis is not a wasteful exercise devoid of sense: through this procedure, for example, one or more personalized interventions can be identified and therefore even for this reason, alone, more effective.

References

2. Pinel JPG. Biopsychology. Boston, Massachusetts: Pearson; 2011.

3. Filipek PA, Accardo PJ, Baranek GT, Cook EH, Dawson G, Gordon B, et al. The screening and diagnosis of autistic spectrum disorders 1. Autism. 2013 Oct 8:11-56.

4. London E. The role of the neurobiologist in redefining the diagnosis of autism. Brain Pathology. 2007 Oct;17(4):408-11.

5. Morello PC. Macchia, autobiografia di un autistico. Salani; 2016 Feb 11.

6. Grandin T. Pensare in immagini-e altre testimonianze della mia vita di autistica. Edizioni Erickson; 2006.

7. Williams D. Nessuno in nessun luogo. Roma: Armando; 2013.

8. Tribulato E. Autismo e gioco libero autogestito. Milano: Franco Angeli; 2013.

9. Franciosi F. La regolazione emotiva nei disturbi dello spettro autistico. Pisa, Edizioni ETS. 2017.

10. Sullivan HS. Teoria interpersonale della psichiatria. Milano: Feltrinelli Editore; 1962.

11. De Rosa F. Quello che non ho mai detto. Cinisello Balsamo. San Paolo; 2014.

12. Frith U. L'autismo: spiegazione di un enigma. Laterza; 2009.

13. Tribulato E. Bambini da liberare - Una sfida all'autismo. Messina: Centro studi logos ODV. 2020.

14. Silieri L, Lorenzoni L, e Tasso D. Il problema dell'attenzione nella scuola media, in Psicologia e scuola; 1998.

15. Oliverio A. Effetto cocktail party, in Mente e cervello, novembre, 2013.

16. Zavagnini M, De Beni R. La mente che vaga. in Psicologia contemporanea; 2016.

17. Militerni R. Neuropsichiatria Infantile. Idelson-Gnocchi; 2004.

18. Brauner A, Brauner F. Vivere con un bambino autistico. Giunti; 2007.

19. Rapin I, Tuchman RF. Autism: definition, neurobiology, screening, diagnosis. Pediatric Clinics of North America. 2008 Oct 1;55(5):1129-46.

20. Sacks O. An anthropologist on Mars. Seven paradoxical tales. New York: Alfred A. Knopf; 1995.

21. Volkmar FR, Paul R, Rogers SJ, Pelphrey KA. Handbook of Autism and Pervasive Developmental Disorders, Assessment, Interventions, and Policy. United States: John Wiley & Sons; 2014.

22. Sigman M, Dijamco A, Gratier M, Rozga A. Early detection of core deficits in autism. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2004;10(4):221-33.

23. Rutgers AH, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van Ijzendoorn MH, van Berckelaer-Onnes IA. Autism and attachment: a meta-analytic review. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004 Sep;45(6):1123-34.

24. Sigman M, Spence SJ, Wang AT. Autism from developmental and neuropsychological perspectives. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2006;2:327-55.

25. Bird G, Cook R. Mixed emotions: the contribution of alexithymia to the emotional symptoms of autism. Translational Psychiatry. 2013 Jul;3(7):e285.

26. Burgess AF, Gutstein SE. Quality of life for people with autism: Raising the standard for evaluating successful outcomes. Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2007 May;12(2):80-6.

27. Matson JL, Nebel-Schwalm M. Assessing challenging behaviors in children with autism spectrum disorders: A review. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2007 Nov 1;28(6):567-79.

28. Decety J. La forza dell'empatia, in Mente e cervello, n. 89. 2012.

29. Vivanti G, Conghi S. La comprensione del linguaggio nell'autismo, in Psichiatria dell'infanzia e dell'adolescenza, vol. 76; 2009.

30. Noens I, Van Berckelaer‐Onnes I, Verpoorten R, Van Duijn G. The ComFor: an instrument for the indication of augmentative communication in people with autism and intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2006 Sep;50(9):621-32.

31. Landa R. Early communication development and intervention for children with autism. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research reviews. 2007;13(1):16-25.

32. Tager-Flusberg H, Caronna E. Language disorders: autism and other pervasive developmental disorders. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2007 Jun;54(3):469-81, vi.

33. Kanner L. Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Acta Paedopsychiatrica. 1968;35(4):100-36.

34. Williams E, Thomas K, Sidebotham H, Emond A. Prevalence and characteristics of autistic spectrum disorders in the ALSPAC cohort. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2008 Sep;50(9):672-7.

35. Lam KS, Aman MG. The Repetitive Behavior Scale-Revised: independent validation in individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2007 May;37:855-66.

36. Johnson CP, Myers SM. Identification and evaluation of children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2007 Nov 1;120(5):1183-215.

37. Prizant BM, Duchan JF. The functions of immediate echolalia in autistic children. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders. 1981 Aug;46(3):241-9.

38. De Ajuriaguerra J, Marcelli D. Psicopatologia del bambino. Milano: Masson Italia; 1986.

39. Jones W, Carr K, Klin A. Absence of preferential looking to the eyes of approaching adults predicts level of social disability in 2-year-old toddlers with autism spectrum disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2008 Aug 4;65(8):946-54.

40. Bonino S. Il sé massimo e il no dell'altro. Psicologia Contemporanea. 2005(182).

41. Ming X, Brimacombe M, Wagner GC. Prevalence of motor impairment in autism spectrum disorders. Brain and Development. 2007 Oct 1;29(9):565-70.

42. Notbohm E. 10 cose che ogni bambino con autismo vorrebbe che tu sapessi. Trento: Erikson; 2015.

43. Treffert DA. The savant syndrome: an extraordinary condition. A synopsis: past, present, future. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2009 May 27;364(1522):1351-7.

44. Plaisted Grant K, Davis G. Perception and apperception in autism: rejecting the inverse assumption. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2009 May 27;364(1522):1393-8.

45. Geschwind DH. Advances in autism. Annual Review of Medicine. 2009 Feb 18;60(1):367-80.

46. Rogers SJ, Ozonoff S. Annotation: what do we know about sensory dysfunction in autism? A critical review of the empirical evidence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005 Dec;46(12):1255-68.

47. Ben-Sasson A, Hen L, Fluss R, Cermak SA, Engel-Yeger B, Gal E. A meta-analysis of sensory modulation symptoms in individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2009 Jan;39:1-1.

48. Fournier KA, Hass CJ, Naik SK, Lodha N, Cauraugh JH. Motor coordination in autism spectrum disorders: a synthesis and meta-analysis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2010 Oct;40:1227-40.

49. Dominick KC, Davis NO, Lainhart J, Tager-Flusberg H, Folstein S. Atypical behaviors in children with autism and children with a history of language impairment. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2007 Mar 1;28(2):145-62.

50. Erickson CA, Stigler KA, Corkins MR, Posey DJ, Fitzgerald JF, McDougle CJ. Gastrointestinal factors in autistic disorder: a critical review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2005 Dec;35:713-27.

51. Buie T, Campbell DB, Fuchs III GJ, Furuta GT, Levy J, VandeWater J, et al. Evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment of gastrointestinal disorders in individuals with ASDs: a consensus report. Pediatrics. 2010 Jan 1;125(Supplement_1):S1-8.

52. Schmahl C. Farsi male per farsi bene, in Mente e cervello, n. 98. 2013.

53. Frye RE, Rossignol DA. Treatments for biomedical abnormalities associated with autism spectrum disorder. Frontiers in Pediatrics. 2014 Jun 27;2:66.

54. Lee TM, Lee KM, Lee CY, Lee HC, Tam KW, Loh EW. Effectiveness of N-acetylcysteine in autism spectrum disorders: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2021 Feb;55(2):196-206.

55. Ghanizadeh A, Akhondzadeh S, Hormozi M, Makarem A, Abotorabi-Zarchi M, Firoozabadi A. Glutathione-related factors and oxidative stress in autism, a review. Current Medicinal Chemistry. 2012 Aug 1;19(23):4000-5.

56. Mayer EA, Padua D, Tillisch K. Altered brain‐gut axis in autism: comorbidity or causative mechanisms?. Bioessays. 2014 Oct;36(10):933-9.

57. Williams BL, Hornig M, Buie T, Bauman ML, Cho Paik M, Wick I, et al. Impaired carbohydrate digestion and transport and mucosal dysbiosis in the intestines of children with autism and gastrointestinal disturbances. PLoS One. 2011;6(9):e24585.

58. Ehlers S, Gillberg C. The epidemiology of Asperger syndrome: A total population study. Journal of hild Psychology and Psychiatry. 1993 Nov;34(8):1327-50.

59. Klin A. Autism and Asperger syndrome: an overview. Revista Brasileira De Psiquiatria (Sao Paulo, Brazil: 1999). 2006 May 1;28:S3-11.

60. McPartland J, Klin A. Asperger's syndrome. Adolesc Med Clin. 2006 Oct;17(3):771-88; abstract xiii.

61. Bruer-Thompson C. "Overlapping Behavioral Characteristics of FASD's & Related Mental Health Diagnosis". 2019. Available from: www.fasdfamilies.com.

62. Lange S, Rehm J, Anagnostou E, Popova S. Prevalence of externalizing disorders and Autism Spectrum Disorders among children with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder: systematic review and meta-analysis. Biochemistry and Cell Biology. 2018;96(2):241-51.

63. National Fragile X Foundation. Autism and Fragile X Syndrome. 2013.

64. Casanova EL, Baeza-Velasco C, Buchanan CB, Casanova MF. The relationship between autism and ehlers-danlos syndromes/hypermobility spectrum disorders. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2020 Dec 1;10(4):260.

65. Cederlöf M, Larsson H, Lichtenstein P, Almqvist C, Serlachius E, Ludvigsson JF. Nationwide population-based cohort study of psychiatric disorders in individuals with Ehlers–Danlos syndrome or hypermobility syndrome and their siblings. BMC Psychiatry. 2016 Dec;16:1-7.

66. Siasos G, Tsigkou V, Kosmopoulos M, Theodosiadis D, Simantiris S, Tagkou NM, et al. Mitochondria and cardiovascular diseases-from pathophysiology to treatment. Ann Transl Med. 2018 Jun;6(12):256.

67. El-Hattab AW, Scaglia F. Mitochondrial Cardiomyopathies. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine. 2016 Jul 25;3:25.

68. Finsterer J, Zarrouk Mahjoub S. Mitochondrial toxicity of antiepileptic drugs and their tolerability in mitochondrial disorders. Expert Opinion on Drug Metabolism & Toxicology. 2012 Jan 1;8(1):71-9.

69. Mithal DS, Kurz JE. Anticonvulsant Medications in Mitochondrial Disease. Pediatric Neurology Briefs. 2017 Nov 10;31(3):9.

70. Finsterer J, Segall L. Drugs interfering with mitochondrial disorders. Drug and Chemical Toxicology. 2010 Apr 1;33(2):138-51.

71. de Oliveira MR. Vitamin A and Retinoids as Mitochondrial Toxicants. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. 2015;2015:140267.

72. Pardo CA, Vargas DL, Zimmerman AW. Immunity, neuroglia and neuroinflammation in autism. International Review of Psychiatry. 2005 Jan 1;17(6):485-95.

73. Gesundheit B, Rosenzweig JP, Naor D, Lerer B, Zachor DA, Procházka V, et al. Immunological and autoimmune considerations of Autism Spectrum Disorders. Journal of autoimmunity. 2013 Aug 1;44:1-7.

74. Gandal MJ, Anderson RL, Billingslea EN, Carlson GC, Roberts TP, Siegel SJ. Mice with reduced NMDA receptor expression: more consistent with autism than schizophrenia?. Genes, Brain and Behavior. 2012 Aug;11(6):740-50.

75. Williams ZJ. Prevalence of Strabismus in Individuals on the Autism Spectrum: A Meta-Analysis. medRxiv. 2021.

76. Danesh AA, Lang D, Kaf W, Andreassen WD, Scott J, Eshraghi AA. Tinnitus and hyperacusis in autism spectrum disorders with emphasis on high functioning individuals diagnosed with Asperger's syndrome. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology. 2015 Oct 1;79(10):1683-8.

77. Zafeiriou DI, Ververi A, Vargiami E. Childhood autism and associated comorbidities. Brain Dev. 2007 Jun;29(5):257-72.

78. Smalley SL. Autism and tuberous sclerosis. J Autism Dev Disord. 1998 Oct;28(5):407-14.

79. Harrison JE, Bolton PF. Annotation: tuberous sclerosis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1997 Sep;38(6):603-14.

80. Endres D, Dersch R, Stich O, Buchwald A, Perlov E, Feige B, et al. Vitamin D deficiency in adult patients with schizophreniform and Autism Spectrum Syndromes: a one-year cohort study at a German tertiary care hospital. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2016 Oct 6;7:168.

81. Zhang Y, Hodgson NW, Trivedi MS, Abdolmaleky HM, Fournier M, Cuenod M, et al. Decreased Brain Levels of Vitamin B12 in Aging, Autism and Schizophrenia. PLoS One. 2016 Jan 22;11(1):e0146797.

82. Sun C, Zou M, Zhao D, Xia W, Wu L. Efficacy of Folic Acid Supplementation in Autistic Children Participating in Structured Teaching: An Open-Label Trial. Nutrients. 2016 Jun 7;8(6):337.

83. Frye RE, Slattery J, Delhey L, Furgerson B, Strickland T, Tippett M, et al. Folinic acid improves verbal communication in children with autism and language impairment: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Molecular Psychiatry. 2018 Feb;23(2):247-56.

84. Yasuda H, Tsutsui T. Assessment of infantile mineral imbalances in autism spectrum disorders (ASDs). Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2013 Nov 11;10(11):6027-43.

85. Stewart PA, Hyman SL, Schmidt BL, Macklin EA, Reynolds A, Johnson CR, et al. Dietary Supplementation in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders: Common, Insufficient, and Excessive. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2015 Aug;115(8):1237-48.

86. Sauer AK, Stanton JE, Hans S, Grabrucker AM. Autism Spectrum Disorders: Etiology and Pathology. In: Grabrucker AM (Editor). Autism Spectrum Disorders. Brisbane, Australia: Exon Publications; 2021