Abstract

Dental fear and anxiety can have a significant effect on an individual, ultimately leading to a poor oral health-related quality of life. Many develop fear and anxiety due to an unfortunate experience at the dentist during their childhood. Dentists, with proper training, can treat children and provide behavior management techniques to complete treatment in a positive manner. These behavior management techniques focus on decreasing the fear and anxiety toward a dental procedure and assisting the child to develop the proper skills needed to cope with such procedures in the future.

Keywords

Fear, Anxiety, Pediatric, Dentistry, Oral health

Introduction

Dental fear or anxiety is very common amongst children and adults. It can be characterized by a feeling of apprehension or unease involving the dental field and the procedures that may occur at a dental office [1]. Approximately 36% of the population has the fear of the dentist with 12% having an extreme fear [2]. Dental fear generally starts in childhood and can be linked to traumatic dental experiences when one is a child [3]. The onset of dental anxiety and fear was found to have started in childhood [4]. Patients are less likely to seek dental care after a poor experience at the dentist and developing a fear resulting in low oral health-related quality of life. Children that experienced more check-up visits before they experienced their first treatment have reported lower levels of dental fear [5]. This shows the more positive experiences a child has at the dentist, the more likely they are not to develop a fear of the dentist and follow up with needed oral health care. It is imperative to provide a level of care to children that enables a child to grow to not be fearful of the dentist, so they may seek future dental care leading to better oral health outcomes.

Pediatric Dentists are trained in behavior guidance techniques to provide a pleasant environment for children. These techniques include communication guidance, direct observation or modeling, tell-show-do, voice control, and positive pre-visit techniques. More advanced techniques may be used if the key techniques are not working, or the child has a disability or is not old enough for these techniques to work [6]. Overall, the author believes that an appointment should be considered a failure if the child leaves in tears and develops a fear of the dentist, even if the needed treatment is completed.

Key Techniques

Many behavior guidance techniques involve proper basic communication guidance techniques. Reflective/active listening is a technique that establishes rapport with a patient [7]. Listening takes effort; hearing is not the same. A dentist must take what the patient is saying and reflect on what is said. This encourages the child to speak and feel heard during treatment. Acknowledging a child’s feeling involves listening to them quietly, acknowledging their feelings, giving a name to their feelings, restating their feelings in the child’s own words, and them summarizing the child’s emotions [8]. Bi-directional communication also allows the child to feel as an active participant in their care [6].

Direct observation or modeling is another technique used and is very useful for families of children when an older sibling does well at the dentist. Allowing a younger sibling to watch their older sibling during an appointment and ask questions, can prevent the fear of a future visit. This allows the patient to familiarize themselves with the dental settings and the particular procedure [6]. This can also be done with filmed modeling, a family member, or another patient.

‘Tell-show-do’ is a classic technique used throughout the day of a pediatric dentist and has been proven to be effective [9,10]. This desensitization technique involves explaining the procedure first, demonstrating how the procedure is done in a nonthreatening manner, then carefully completing the procedure [6]. An example would involve a simple cleaning with a prophy angle. One would tell the patient all that is going to be used including the “spin” toothbrush and the showing the “toothpaste” that will be used. Next the technique can be done on the nail of the patient to show how it does not hurt and so they can experience from a visual, auditory, olfactory, and tactile aspect the experience. Then the procedure would be completed (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Tell-show-do.

Voice control is also utilized, not in a threatening manner as it may sound. This is a deliberate alteration of the voice volume, tone or pace to influence and direct the patient and their behavior [6,11]. The type of intonation this author encourages would be one such as a whisper. When one is having trouble getting a patient to calm or listen, lowering the voice to whisper and getting closer to the patient allows the patient to focus on what the dentist is stating.

Positive reinforcement is one of the most common ways to reward good behavior and encourage a child to want to return to the dentist. This includes praise for particular behaviors and reinforcing behavior with classic toys found in a dental office (Figure 2). Children love being rewarded with a toy at the end of an appointment. A simple bouncy ball after getting a restoration or filling completed can lead the child to having a positive experience. Praising the child with what they did well is important to encourage that behavior in the future [12].

Figure 2. Common toys given at appointments.

Distraction is a technique where the patient’s attention is diverted to avoid the actual procedure being completed [6]. Audio-visual distraction has been shown to be very effective. For example, television as an audio-visual distraction is used in many dental offices to distract a child from the dental treatment. Another example would be audio distraction where the provider is telling a story to divert the child’s attention to the story and not the treatment, or having the child listen to music [13,14]. These techniques are very effective in decreasing anxiety [15,16].

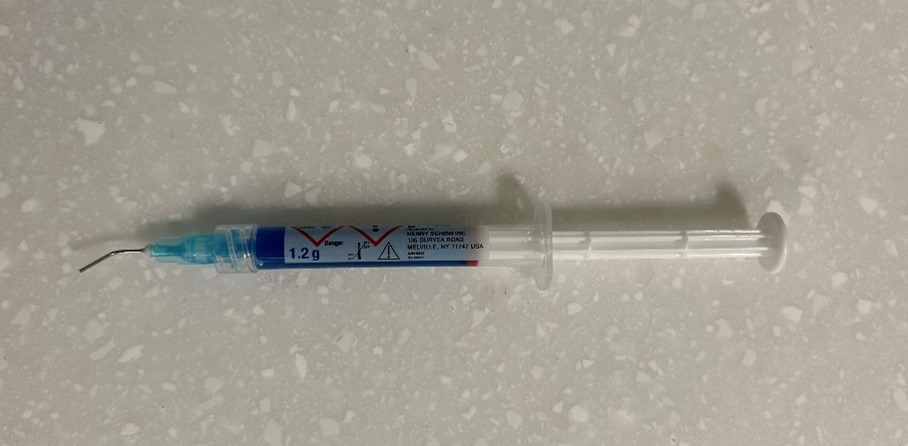

Some patients may benefit from positive pre-visit imagery [6]. This involves looking at positive photographs or images of dentistry prior to a dental appointment. The child can also be given imaging preparing them for a dental procedure and the instruments that will be used. By doing so, the child is prepared for the visit and is not going into an appointment with fear of the unknown. Dental instruments and materials can look quite scary. Providing the child an explanation and visual image of such items can reduce fear at the appointment. For example, dental etchant is used to clean the tooth prior to placing sealants, a common preventive technique used around the age of 6-7 years old when the first permanent molars erupt. Dental etch comes in a syringe and looks like a needle (Figure 3). By explaining that the blue material simply comes out and is “painted” on the tooth like shampoo and is then rinsed off the tooth, will assist the child in getting through an appointment without fear.

Figure 3. Dental etchant used for sealants.

Parents or guardians also have a great influence on the child and how they do in the dental office. If a parent has a positive attitude toward oral health, then they are more likely to establish a dental home for their child and therefore provide more preventative care. This is more likely to lead to prevention of caries and the child is less likely to experience having to complete a more difficult restorative appointment [6]. Parents also transmit their dental fear onto their child [6]. This makes it more challenging for a child to develop a positive attitude toward the dentist. It is important to not only make the experience for the child at each appointment positive, but also the parent.

Advanced Techniques

The key techniques work for most children, however, at times more advanced techniques are needed. Nitrous oxide, sedation, and general anesthesia can additionally be used. The “key techniques” should be considered prior to the advanced techniques. Some children though may not be able to cooperate due to emotional immaturity, a psychological disability or medical disability [6].

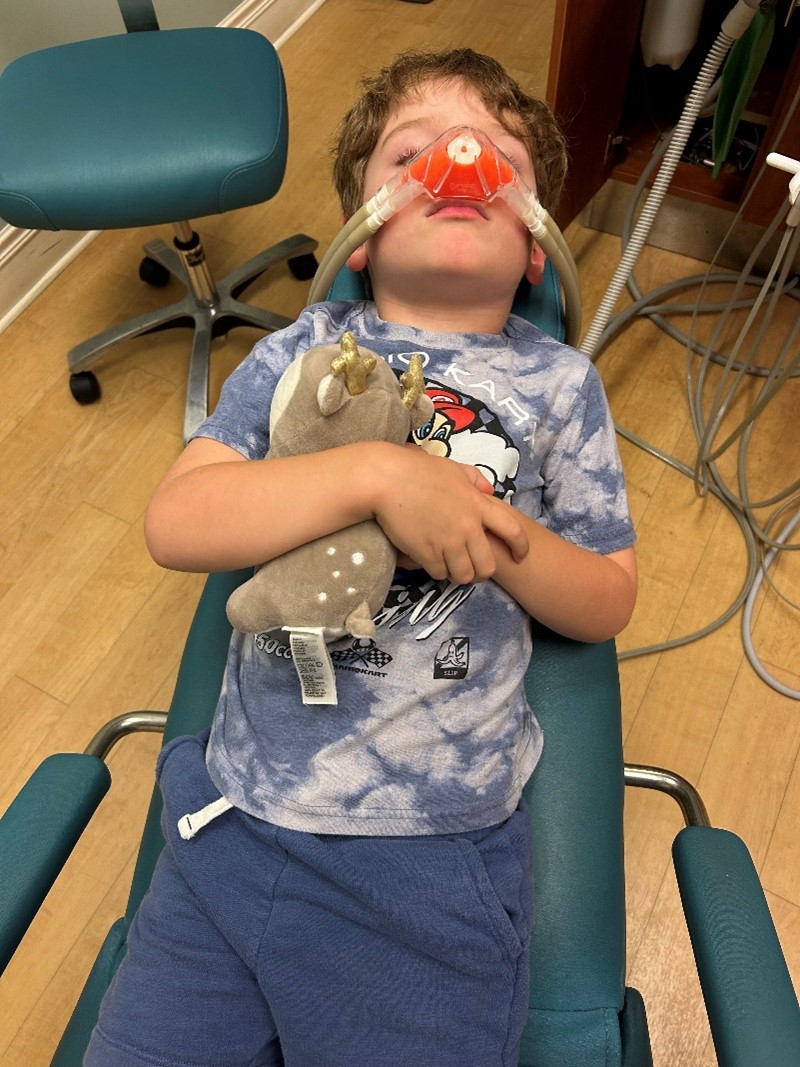

Nitrous oxide inhalation is a technique that many dentists use to provide dental treatment safely (Figure 4). It has multiple mechanisms of action including an analgesic effect and anxiolytic effect. Properties that make it an advanced technique of choice is its rapid onset of action, ability to titrate, and how effects are easy to reverse [17]. In children these properties allow procedures that are not pleasant to be completed, reducing pressure-induced pain and reaction time [18].

Figure 4. Nitrous oxide being administered to a patient.

Sedation can safely be provided for patients unable to cooperate by well-trained dentists. This advanced technique is typically indicated for patients with fear and anxiety where the key techniques do not work or to protect the developing psyche of a child that where the key techniques most likely will not work [6]. This type of technique requires appropriate training by the dentist to provide sedation safely.

General anesthesia allows safe, effective, and high-quality care to patients that are unable to complete treatment in the chair. This technique is considered in more complex cases, including those that involved significant surgical procedures or to decrease the number of anesthetic exposures [6]. Additionally, it is considered for children that are very young, have complex medical conditions, have emergency treatment that is extensive, or patients with neurodevelopmental needs [6,9]. General anesthesia when used, is typically completed either in the hospital, ambulatory surgery center or office setting by an anesthesiologist with the dentist completing the dental treatment.

Conclusion

Dental fear is highly prevalent in many adults worldwide. This leads to poorer oral health outcomes due to the avoidance of regular preventive visits and any dental treatment. By incorporating techniques to provide a positive environment starting at a very young age, dental fear can be greatly reduced. The techniques described provide many ways to assist a child to develop into an adult with less chance of fear of the dentist due to a poor experience while young. The goal is to protect the overall psyche of the child and encourage them to continue to see a dentist when older and therefore have good oral health.

Conflicts of Interest

Not applicable.

Funding Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Drs. John H Unkel and William Piscitelli for their editing of this manuscript.

References

2. Hill KB, Chadwick B, Freeman R, O'Sullivan I, Murray JJ. Adult Dental Health Survey 2009: relationships between dental attendance patterns, oral health behaviour and the current barriers to dental care. Br Dent J. 2013 Jan;214(1):25-32.

3. Berggren U, Meynert G. Dental fear and avoidance: causes, symptoms, and consequences. J Am Dent Assoc. 1984 Aug;109(2):247-51.

4. Locker D, Liddell A, Dempster L, Shapiro D. Age of onset of dental anxiety. J Dent Res. 1999 Mar;78(3):790-6.

5. Ten Berge M, Veerkamp JS, Hoogstraten J. The etiology of childhood dental fear: the role of dental and conditioning experiences. J Anxiety Disord. 2002;16(3):321-9.

6. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Behavior Guidance for the Pediatric Dental Patient. The Reference Manual of Pediatric Dentistry. Chicago, Ill.: American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry; 2023. pp. 359-377.

7. Hamzah HS, Gao X, Yung Yiu CK, McGrath C, King NM. Managing dental fear and anxiety in pediatric patients: A qualitative study from the public's perspective. Pediatr Dent. 2014 Jan-Feb;36(1):29-33.

8. Mostofsky DI, Fortune F. Behavioral Dentistry. 2nd ed. Wiley-Blackwell Publishers; 2014.

9. Paryab M, Arab Z. The effect of Filmed modeling on the anxious and cooperative behavior of 4-6 years old children during dental treatment: A randomized clinical trial study. Dent Res J (Isfahan). 2014 Jul;11(4):502-7.

10. Virupaxi SG. A comparative study of filmed modeling and tell-show-do technique on anxiety in children undergoing dental treatment. Ind J Dent Adv. 2016;8:215-22.

11. Stigers JI. Nonpharmacologic management of children’s behaviors. In: Dean JA, ed. McDonald and Avery’s Dentistry for Child and Adolescent. 10th ed. St. Louis, Mo.: Elsevier; 2016. pp. 286-302.

12. Nash DA. Engaging children's cooperation in the dental environment through effective communication. Pediatr Dent. 2006 Sep-Oct;28(5):455-9.

13. Pande P, Rana V, Srivastava N, Kaushik N. Effectiveness of different behavior guidance techniques in managing children with negative behavior in a dental setting: A randomized control study. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2020 Jul-Sep;38(3):259-65.

14. Kharouba J, Peretz B, Blumer S. The effect of television distraction versus Tell-Show-Do as behavioral management techniques in children undergoing dental treatments. Quintessence Int. 2020;51(6):486-94.

15. Navit S, Johri N, Khan SA, Singh RK, Chadha D, Navit P, et al. Effectiveness and Comparison of Various Audio Distraction Aids in Management of Anxious Dental Paediatric Patients. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015 Dec;9(12):ZC05-9.

16. Singh D, Samadi F, Jaiswal J, Tripathi AM. Stress Reduction through Audio Distraction in Anxious Pediatric Dental Patients: An Adjunctive Clinical Study. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2014 Sep-Dec;7(3):149-52.

17. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Us of Nitrous Oxide for Pediatric Dental Patients. The Reference Manual of Pediatric Dentistry. Chicago, Ill.: American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry; 2023. pp. 393-400.

18. Grønbæk AB, Svensson P, Væth M, Hansen I, Poulsen S. A placebo-controlled, double-blind, crossover trial on analgesic effect of nitrous oxide-oxygen inhalation. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2014 Jan;24(1):69-75.

19. Ba'akdah R, Farsi N, Boker A, Al Mushayt A. The use of general anesthesia in pediatric dental care of children at multi-dental centers in Saudi Arabia. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2008 Winter;33(2):147-53.