Abstract

Metabotropic glutamate (mGlu) receptors are a family of G protein-coupled receptors. These receptors are widely distributed in the brain and are critical for the modulation of synaptic transmission and plasticity. Emerging evidence shows that mGlu receptors themselves are subject to a dynamic posttranslational modification involving protein ubiquitination. Postsynaptic group I mGlu receptors (mGlu1/5) undergo constitutive ubiquitination at lysine sites on their intracellular domains in heterologous cells and neurons. In particular, ligand stimulation triggers rapid ubiquitination of group I receptors to confer a negative feedback regulation. Like mGlu1/5, presynaptic mGlu7 receptors are ubiquitinated by a specific E3 ubiquitin ligase. Robust ubiquitination is also seen in a number of existing synaptic proteins closely associated with mGlu activity, including Homer1a, the activity-regulated cytoskeleton-associated protein Arc/Arg3.1, and the protein interacting with C-kinase 1. Ubiquitination of mGlu receptors targets the receptors to degradation via the proteasome-dependent or -independent pathway or plays nondegradative roles in the regulation of distinct cellular processes such as endocytic trafficking, protein-protein interactions, and mGlu receptor signaling.

Keywords

mGlu, Glutamate, Homer, PICK1, Ubiquitin, Ubiquitination, Proteasome, Degradation

Introduction

The neurotransmitter L-glutamate interacts with ionotropic and metabotropic glutamate (mGlu) receptors in the mammalian brain [1]. mGlu receptors are a family of class C G protein-coupled receptors, and eight mGlu receptor subtypes are subdivided into three functional groups (I-III). Group I receptors (mGlu1/5) are coupled to heterotrimeric Gq proteins. Activation of them causes phospholipase Cβ1 to hydrolyze phosphoinositide into inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate and diacylglycerol, leading to Ca2+ release and protein kinase C (PKC) activation [2,3]. Group II (mGlu2/3) and group III (mGlu4/6/7/8) receptors are coupled to Gi/o proteins. Their activation leads to inhibition of adenylyl cyclase and thus reduction of cAMP formation and protein kinase A activity. In addition to these canonical signaling pathways, mGlu receptors modulate many other signaling molecules and ion channels. Group I receptors are primarily localized at postsynaptic sites, while group II/III receptors are principally presynaptic. As a set of receptors that are widely distributed throughout the brain, mGlu receptors are actively involved in the regulation of numerous neuronal and synaptic activities and are linked to various neurological and neuropsychiatric disorders [2,3].

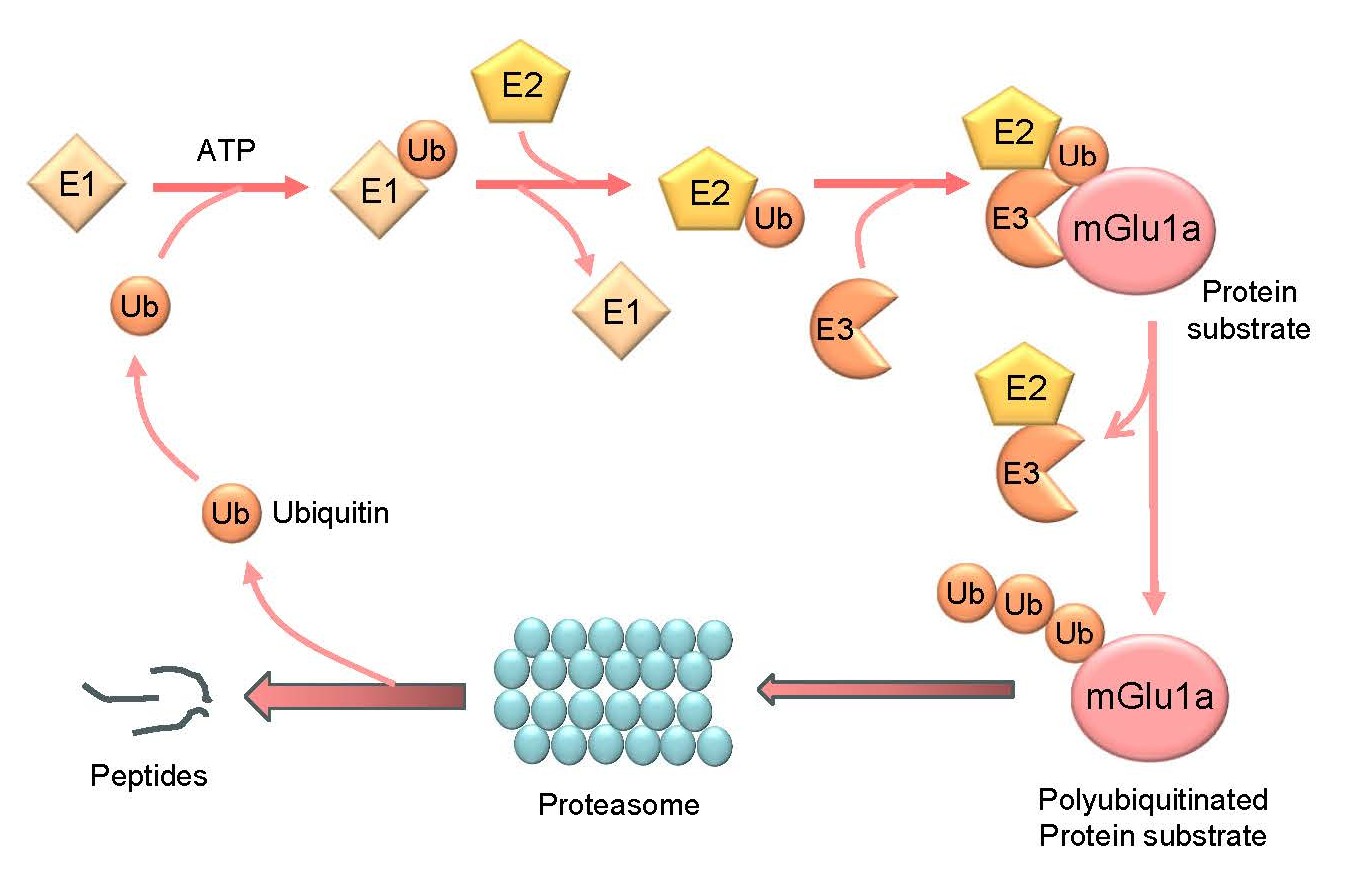

Ubiquitination is an important posttranslational modification for regulating function of existing proteins under constitutive and activity-dependent conditions [4,5]. As a tightly regulated enzymatic cascade (Figure 1), protein ubiquitination starts with activation of ubiquitin, a highly conserved 76-amino acid polypeptide, by the ubiquitin-activating enzyme (E1). Active ubiquitin is then transferred to the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2). Through the ubiquitin ligase (E3), the last C-terminal amino acid of ubiquitin (G76) binds to mostly a lysine residue on the target protein via a covalent isopeptide bond. In this step, one of the hundreds of E3 ligases confers specificity to the ubiquitination reaction. Typically, ubiquitination repeats itself until the assembly of a polyubiquitin chain on the substrate protein. A ubiquitin K48-linked polyubiquitin chain is the most abundant type of polyubiquitination and is the canonical signal for directing proteins to the 26S proteasome for degradation, while K63-linked polyubiquitination can serve as a reversible posttranslational modification to play nondegradative roles in cellular processes such as inflammatory signaling, DNA repair, endocytosis, etc. or can target proteins to degradation via the autophagy-lysosomal pathway [4,5]. In addition, conjugation of a single ubiquitin molecule to one protein at a single residue (i.e., monoubiquitination) or multiple residues (multi-monoubiquitination) can affect the trafficking, interaction, and other activities of tagged proteins in a proteasome-independent manner [6].

Protein ubiquitination has emerged as a robust mechanism for the dynamic regulation of synaptic transmission and plasticity. It is known now that the active ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) resides in the presynaptic active zone as well as the postsynaptic density (PSD) and regulates turnover and function of a set of proteins at both pre- and postsynaptic sites [7–10]. mGlu receptors are among a large number of synaptic proteins subjected to ubiquitination. Among the mGlu receptor subtypes investigated so far, mGlu1/5 and mGlu7 have been found to be vigorously regulated by the ubiquitination mechanism. Available evidence shows that constitutive and activity-dependent ubiquitination of presynaptic mGlu7 and postsynaptic mGlu1/5 receptors leads to UPS-dependent or -independent degradation of the receptors or directly affects their endocytosis and function. Functional ubiquitination also occurs to synaptic proteins that are closely associated with mGlu receptors. Taken together, ubiquitination plays degradative or nondegradative roles in controlling stability, trafficking, subcellular distributions, protein-protein interactions, and signaling of mGlu receptors and thus fine-tunes the strength and efficacy of glutamatergic transmission.

Group I mGlu Receptors

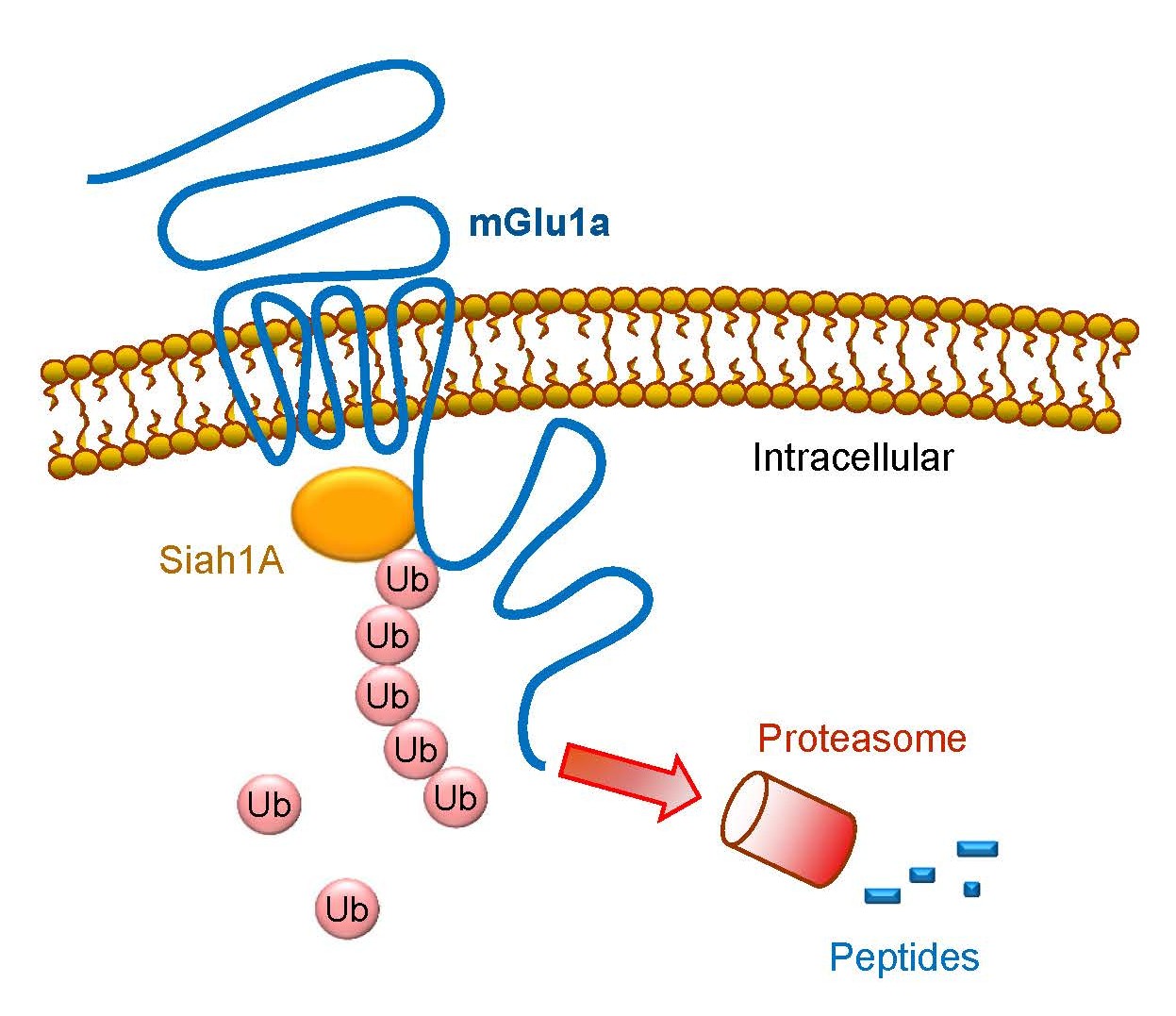

Group I receptors are the first subgroup of mGlu receptors shown to be subject to the regulation by the ubiquitination-dependent mechanism. It is well known that a variety of E3 ligases carry out ubiquitination. Each ligase recognizes a specific target protein and brings it to a discrete fate of either degradation or other cellular processes. In the case of group I receptors, an early study with yeast two-hybrid screening revealed that seven in absentia homolog 1A (Siah1A), a member of the RING-finger-containing E3 ubiquitin ligases, selectively interacted with mGlu1/5 [11]. Siah1A directly bound to the proximal region of mGlu1a/5a C-terminus (CT) (Figure 2), while Siah1A did not interact with mGlu2 and mGlu7 in their CT regions [11]. The Siah1A-interacting sequence is present in the splice variants with long (mGlu1a and mGlu5a/5b) but not short (mGlu1b/1f/1d and mGlu5d) CT domains. The interaction of full-length mGlu1a with Siah1A was confirmed in transfected COS-7 mammalian cells [11] and was activity-dependently induced in hippocampal neurons [12]. Moreover, Siah1A and group I mGlu mRNAs are co-expressed in the same cell populations in the mouse hippocampus and cerebellum.

The interaction between Siah1A and mGlu1/5 may enable Siah1A to serve as a functional E3 ligase to specifically ubiquitinate and degrade existing receptor proteins at the posttranslational level. Indeed, co-transfection of Siah1A induced polyubiquitination of recombinant mGlu1a and mGlu5 proteins in HEK293 cells [13]. Multiple lysine residues spanning from intracellular loops to the CT region of mGlu5 were ubiquitinated by Siah1A (Table 1). The Siah1A-induced polyubiquitination of mGlu1a was causally linked to subsequent degradation of the receptors via the 26S proteasome, resulting in acceleration of the mGlu1a protein turnover and loss of mGlu1a at the protein but not mRNA level in transfected cells [13]. Meanwhile, Siah1A did not alter mGlu3 and mGlu7 expression. Of note, in a heterologous expression cell line (rat sympathetic superior cervical ganglion neurons), co-expressed Siah1A attenuated group I mGlu-mediated inhibition of Ca2+ currents, although this effect was likely due to a direct association of Siah1A with group I receptors rather than a result of targeting the receptors to the proteasome [14].

Ubiquitination of group I receptors could be a regulated event. The cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator-associated ligand (CAL) through its PSD-95/discs large/ZO-1 (PDZ) homolog domain bound to the distal end of mGlu5a CT [15]. As such, CAL inhibited ubiquitination and degradation of mGlu5a and elevated receptor expression at the posttranslational (i.e., protein but not mRNA) level. Unlike CAL, Homer3 positively regulates the proteasomal degradation of mGlu1a receptors. Homer3, a long isoform of the Homer scaffold protein family, but not Homer1/2 bound to S8 ATPase, a subunit of the 26S proteasome [16]. Since Homer3 is known to bind to mGlu1a, Homer3 links mGlu1a to S8 ATPase to form an mGlu1a/Homer3/S8 ATPase complex in neurons in vivo. As a result, Homer3 enhances ubiquitination of mGlu1a receptors and delivers the ubiquitinated mGlu1a to the proteasome for degradation.

Ligand activation of group I receptors can trigger a negative feedback loop involving a ubiquitination link. The group I mGlu agonist DHPG induced rapid polyubiquitination of mGlu1 at a K1112 site in HEK293 cells and cultured hippocampal neurons [17]. UBEI-41 (also known as PYR-41), an inhibitor of the E1 activating enzyme in the ubiquitin cascade, and siRNA knockdown of Siah1A blocked the DHPG-stimulated polyubiquitination of mGlu1 receptors. Both UBEI-41 and Siah1a siRNAs also blocked the DHPG-induced endocytosis of mGlu1 receptors, indicating a role of ubiquitination in the agonist-induced internalization of the receptors. In other studies, ligand activation of mGlu5 receptors triggered PKC to phosphorylate a residue (S901) on the mGlu5 CT, which in turn disrupted the binding of calmodulin to mGlu5 and therefore promoted the binding of the E3 ligase Siah1A to the receptors [12,18]. Siah1A then induced monoubiquitination of mGlu5 and sorted the receptors into the late endosomal/lysosomal pathway. The accelerated lysosomal degradation of mGlu5 led to a decrease in expression of mGlu5 receptors in heterologous HeLa cells and cultured hippocampal neurons [12]. The above results generally establish a ubiquitination-dependent feedback model in which agonist stimulation induces ubiquitination of group I receptors, which results in internalization or degradation of the ubiquitinated receptors. Based on this model, inhibition of the negative feedback ubiquitination is reasoned to enhance group I receptor functions. In fact, inhibition of ubiquitination by UBEI-41 or knockdown of Siah1A enhanced a series of DHPG-induced events, including 1) membrane depolarization, 2) phosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK), 3) endocytosis of AMPA receptors, and 4) long-term depression (LTD), in heterologous cells or hippocampal neurons [17,19]. Of note, the proteasome inhibitor lactacystin produced the similar effect in these events [19]. Thus, the proteasomal pathway, in addition to the lysosomal pathway, participates in the degradation of group I receptors implicated in the negative feedback regulation of the receptors.

The dynamic balance between ubiquitination and deubiquitination is essential for controlling the turnover of modified proteins. Thus, deubiquitinating enzymes that cleave ubiquitin from substrate proteins are equally important for determining the ubiquitination level of group I receptors, although studies of this kind are limited. One study found that a deubiquitinating enzyme, Usp4, bound to the CT region of A2A adenosine receptors and deubiquitinated the receptors [20]. However, the Usp4 interaction was not seen with the mGlu5 receptors. Future studies are warranted to identify deubiquitinating enzymes that act to deubiquitinate group I receptors as well as other subgroups of mGlu receptors.

|

Protein |

Ubiquitination site |

E3 ligase |

Physiological impact |

|

mGlu1 |

Multiple lysine sites in intracellular loops and CT, including K1112 in CT |

Siah1A |

Increase mGlu1 degradation via proteasomes and promote agonist-induced endocytosis |

|

mGlu5 |

Multiple lysine sites in intracellular loops and CT |

Siah1A |

Accelerate mGlu5 degradation via lysosomes and proteasomes |

|

mGlu7 |

K688 and K689 in second intracellular loop and multiple lysine sites in CT |

Nedd4 |

Increase mGlu7 degradation via proteasomes and lysosomes and promote agonist-induced endocytosis |

|

Homer1a |

ND |

ND |

Increase Homer1a degradation via |

|

Arc |

K268 and K269 |

Triad3A |

Promote Arc to proteasomal degradation, negatively regulate mGlu-LTD, and reduce group I agonist-stimulated Ca2+ release |

|

PICK1 |

Monoubiquitination rather than polyubiquitination |

Parkin |

Reduce PICK1 function in a proteasome-independent manner |

|

RIM1 |

ND |

SCRAPPER |

Increase proteasomal degradation of RIM1 |

|

ND: Not Determined. See text for other abbreviations. |

|||

Group III mGlu Receptors

Group III receptors include four subtypes (mGlu4/6/7/8). Emerging evidence reveals that presynaptic mGlu7 receptors are subject to ubiquitination [21,22]. Dimers and multimers although not monomers of recombinant mGlu7 receptors were ubiquitinated at multiple lysine sites on both CT and an intracellular loop in transfected HEK293T cells [21] (Table 1). Ubiquitination of mGlu7 was constitutively active and could be upregulated in an activity-dependent fashion in response to agonist stimulation. Native mGlu7 receptors were also sensitive in its ubiquitination to ligand stimulation in cultured rat cortical neurons. In searching for an E3 ligase specific for mGlu7 ubiquitination, Nedd4 (neural precursor cell-expressed developmentally down-regulated 4) was found to play such a role in constitutive and agonist-stimulated ubiquitination. Moreover, β-arrestins participate in the ligand-stimulated ubiquitination of mGlu7 by recruiting Nedd4 to the activated receptors.

Ubiquitin contains seven lysine residues (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, and K63) and an N-terminal methionine (M1) that serve as points for forming polyubiquitination chains. K48- and K63-linked ubiquitin chains are the two best-characterized types of ubiquitin chains. The former targets the substrate protein to the proteasome for degradation, whereas the latter is not associated with the proteasome and instead may direct the substrate protein to other processes, including endocytic trafficking. The K63-linked ubiquitin chain was observed in mGlu7 receptors [21]. Thus, mGlu7 ubiquitination is likely involved in receptor endocytosis. The finding that surface-expressed but not intracellular mGlu7 receptors underwent the agonist-induced ubiquitination [21] seems to imply that surface mGlu7 receptors are sorted to go through the endocytic route. In support of this, an E1 activating enzyme inhibitor and siRNA knockdown of Nedd4 reduced the agonist-induced mGlu7 ubiquitination and endocytosis. In addition to the K63-linked chain, the K48-linked ubiquitin chain was present in mGlu7 receptors, indicating a role of ubiquitination in signaling mGlu7 to degradation. Indeed, agonist stimulation induced a Nedd4/ubiquitination-sensitive decrease in total mGlu7 protein levels [21]. The proteasome inhibitor MG132 reduced this decrease, suggesting a role of the proteasome in the degradative event. In addition, the lysosome inhibitor leupeptin produced the similar effect as MG132. Thus, ubiquitination also sorts mGlu7 into early and late endosomes, followed by degradation in lysosomes.

Other Synaptic Proteins Associated with mGlu Receptors

In addition to mGlu receptor themselves, mGlu-associated proteins undergo ubiquitination. Ubiquitination of these proteins regulates their abundance and function, which in turn exerts a significant impact on the expression, subcellular distribution, and signaling of mGlu receptors. For example, Homer proteins are a family of adaptor proteins enriched at postsynaptic sites and are associated with multiple synaptic proteins, especially the group I receptors. A short-form Homer protein, i.e., Homer1a, was robustly ubiquitinated in HEK293T cells [23]. This ubiquitination targeted Homer1a to degradation by the proteasomal but not lysosomal pathway under normal conditions. Inhibition of proteasomes thus enhanced Homer1a protein levels and furthermore increased delivery of Homer1a to synaptic sites in cultured hippocampal neurons [24]. In contrast to Homer1a, long-form Homer proteins (Homer1b/c, Homer2, and Homer3) were resistant to proteasomal degradation. Homer was discovered as a postsynaptic protein that specifically binds to a consensus proline-rich sequence in the CT region of group I mGlu receptors [25]. Activity-induced Homer1a can disrupt the cross-linking action of constitutively expressed long Homer isoforms to modulate surface expression of group I receptors and group I receptor-mediated Ca2+ signaling and other activities [26,27]. It is likely that activity-dependent ubiquitination and degradation of Homer1a serve as a molecular mechanism underlying the regulation of expression and function of Homer1a in relation to the modulation of glutamatergic transmission and synaptic plasticity.

The activity-regulated cytoskeleton-associated protein Arc/Arg3.1 (Arc) is another synaptic protein that is associated with group I receptor-mediated synaptic plasticity and is regulated by ubiquitination. As an immediate early gene product, Arc is rapidly induced via an increase in its transcription and translation in response to changing cellular and synaptic input. Induced Arc then regulates various activities at glutamatergic synapses. For instance, in response to DHPG, Arc is induced to facilitate endocytosis of AMPA receptors, an event implicated in group I mGlu-LTD [28]. Many newly synthesized synaptic proteins are subject to ubiquitin-dependent turnover to ensure a tight control of their quantities at synaptic sites and a discrete temporal window for their actions [29,30]. Arc is among these highly dynamic proteins and was ubiquitinated after synthesis at K268 and K269 sites in heterologous cells or neurons [31–33] (Table 1). Ubiquitination of Arc promoted Arc to proteasomal degradation. Given that Arc-mediated endocytosis of AMPA receptors is a core element in group I mGlu-LTD, Arc ubiquitination may negatively regulate the mGlu-LTD. In fact, enhanced Arc ubiquitination by overexpression of an E3 ubiquitin ligase (Triad3A) reduced DHPG-induced synaptic depression in cultured hippocampal neurons, whereas knockdown of Triad3A produced the opposite effect [33]. In a mutant mouse line in which ubiquitin-dependent degradation of Arc is disabled, DHPG induced a higher level of Arc expression and a higher amplitude of LTD at the Schaffer collateral–commissural pathway in the CA1 region of hippocampal slices [34]. Similarly, disrupting Arc ubiquitination enhanced the DHPG-stimulated Ca2+ release from the endoplasmic reticulum [35]. In in vitro and in vivo seizure models, the reduction of ubiquitin-dependent degradation of Arc enhanced the hippocampal group I mGlu-LTD in vitro and reduced it in vivo [36]. In addition to LTD, Arc ubiquitination supports the induction and expression of long-term potentiation (LTP) in the hippocampal CA1 area [37]. Of note, inconsistent results were reported regarding the role of Ube3A (also known as E6AP), an E3 ubiquitin enzyme, in binding and ubiquitinating Arc [28].

Unlike its effects in the CA1 area, DHPG alone did not induce LTD at the mossy fiber pathway in the CA3 region of rat hippocampal slices [38]. Co-activation of the G protein-coupled estrogen receptor 1 was required for the agonist to induce LTD. Notably, this form of mGlu-LTD is associated with the DHPG-induced rapid ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of the AMPA receptor GluA1 subunit but not Arc. In addition to GluA1, mGlu5 regulates glycine receptor ubiquitination in an activity-dependent manner. In mouse spinal cord dorsal horn neurons, activation of postsynaptic mGlu5 receptors by DHPG in the presence of mGlu1 antagonist or by the mGlu5 agonist CHPG stimulated ERK to phosphorylate the glycine receptor α1ins subunit at an S380 site. This phosphorylation facilitated monoubiquitination of α1ins subunits, leading to α1ins endocytosis and inhibition of overall glycinergic transmission [39].

The protein interacting with C-kinase 1 (PICK1) is a synaptic scaffold protein that interacts with a number of synaptic receptors, transporters, and ion channels [40]. Among these PICK1-interacting proteins is the presynaptic mGlu7 receptor. As a PDZ-domain-containing protein, PICK1 directly binds to the PDZ ligand at the extreme CT of mGlu7 [41–46]. Such binding is critical for the regulation of phosphorylation, presynaptic clustering, synaptic localization, surface stability, and signaling of mGlu7 receptors. Notably, PICK1 is among synaptic scaffold proteins subjected to ubiquitination. Parkin, an E3 ubiquitin ligase, bound to PICK1 in a PDZ-dependent manner, which enables Parkin to monoubiquitinate but not polyubiquitinate the target [47]. Consistent with the notion that monoubiquitination could regulate the function of tagged proteins without necessarily sorting them to degradation by the proteasome, Parkin reduced the PICK1-dependent potentiation of acid-sensing ion channels, while it did not promote PICK1 to proteasomal degradation. Given the robust linkage of PICK1 with mGlu7, the Parkin-mediated monoubiquitination of PICK1 might have a profound influence over mGlu7 receptors, an interesting topic to be investigated in future studies. In addition to PICK1, Rab3-interacting molecule 1 (RIM1) is a scaffold protein in the active zone. One study found that RIM1 was ubiquitinated by a presynaptically-localized E3 ubiquitin ligase, SCRAPPER, and was degraded in the proteasome [48]. Further studies observed that SCRAPPER plays critical roles in regulating the thresholds of LTP/LTD in mouse hippocampal CA3-CA1 synapses [49] and in determining the formation of hippocampus-dependent fear memory in mice [50]. Notably, RIM1, like PICK1, is a known PDZ-domain-containing protein. Whether RIM1 binds to the PDZ ligand of any presynaptic mGlu receptors is currently unclear.

Conclusions

Presynaptic mGlu7 receptors undergo constitutive and agonist-induced ubiquitination. Postsynaptic group I receptors are also ubiquitinated. Agonist stimulation triggers polyubiquitination of mGlu1 to promote a negative feedback regulation. Like mGlu receptors, a set of mGlu-associated synaptic proteins, including Homer1a, Arc and PICK1, are subject to ubiquitination. Specific E3 ubiquitin ligases catalyze the ubiquitination of a specific mGlu substrate. All types of ubiquitination (mono- versus polyubiquitination) are physiologically relevant. They could either direct mGlu receptors/synaptic proteins to degradation via the UPS or autophagy/lysosomal pathway or play nondegradative roles in the regulation of their trafficking, distribution patterns, protein-protein interactions, and functions.

It should be pointed out that preclinical studies on mGlu ubiquitination biology are still at an early stage. Several lines of future studies are needed to gain in-depth understanding of biochemical and physiological properties of mGlu ubiquitination in a constitutive state or in response to changing synaptic input. First, additional E3 ubiquitin ligases may be discovered to possess the ability to ubiquitinate mGlu receptors. The nature that E3 ligases confer specificity of substrate proteins is noteworthy. Additionally, deubiquitination enzymes are worth more attention as little is known about their roles in the delicate balance controlling mGlu ubiquitination. Second, mGlu receptors are knowingly subject to other types of subtle posttranslational modifications such as phosphorylation, sumoylation, etc., in addition to ubiquitination [51,52]. Active crosstalk is believed to occur among these different modification processes. Future studies can aim to explore and characterize their potential crosstalk activities. Finally, timely attempts are much needed to link the knowledge of mGlu ubiquitination to brain illnesses. Ubiquitination of mGlu receptors and associated proteins may be a vulnerable event and may undergo adaptive changes during the development of chronic brain diseases, which contributes to the receptor and synaptic plasticity critical for the pathogenesis and symptomology of various brain disorders.

Author Contributions

LMM and JQW planned and wrote the manuscript and prepared the figure. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgment

The authors want to thank the NIH for the research grant that promotes the production of this and other publications.

Funding

This study was in part supported by a grant from the NIH (R01-MH061469 to JQW). JQW holds the Westport Anesthesia/Missouri Endowed Chair.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI Statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

References

2. Niswender CM, Conn PJ. Metabotropic glutamate receptors: physiology, pharmacology, and disease. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2010;50:295–322.

3. Nicoletti F, Bockaert J, Collingridge GL, Conn PJ, Ferraguti F, Schoepp DD, et al. Metabotropic glutamate receptors: From the workbench to the bedside. Neuropharmacology. 2011;60:1017–41.

4. Husnjak K, Dikic I. Ubiquitin-binding proteins: decoders of ubiquitin-mediated cellular functions. Annu Rev Biochem. 2012;81:291–322.

5. Swatek KN, Komander D. Ubiquitin modifications. Cell Research. 2016;26:399–422.

6. Oh E, Akopian D, Rape M. Principles of ubiquitin-dependent signaling. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2018;34:137–62.

7. Yi JJ, Ehlers MD. Emerging roles for ubiquitin and protein degradation in neuronal function. Pharmacol Rev. 2007;59:14–39.

8. Mabb AM, Ehlers MD. Ubiquitination in postsynaptic function and plasticity. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2010;26:179–210.

9. Goo MS, Scudder SL, Patrick GN. Ubiquitin-dependent trafficking and turnover of ionotropic glutamate receptors. Front Mol Neurosci. 2015;8:60.

10. Mabb AM. Historical perspective and progress on protein ubiquitination at glutamatergic synapses. Neuropharmacology. 2021;196:108690.

11. Ishikawa K, Nash SR, Nishimune A, Neki A, Kaneko S, Nakanishi S. Competitive interaction of seven in absentia homolog-1A and Ca2+/calmodulin with the cytoplasmic tail of group 1 metabotropic glutamate receptors. Genes Cells. 1999;4:381–90.

12. Ko SJ, Isozaki K, Kim I, Lee JH, Cho HJ, Sohn SY, et al. PKC phosphorylation regulates mGluR5 trafficking by enhancing binding of Siah-1A. J Neurosci. 2012;32:16391–401.

13. Moriyoshi K, Lijima K, Fujii H, Ito H, Cho Y, Nakanishi S. Seven in absentia homolog 1A mediates ubiquitination and degradation of group 1 metabotropic glutamate receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:8614–9.

14. Kammermeier PJ, Ikeda SR. A role for Seven in Absentia Homolog (Siah1a) in metabotropic glutamate receptor signaling. BMC Neurosci. 2001;2:15.

15. Cheng S, Zhang J, Zhu P, Ma Y, Xiong Y, Sun L, et al. The PDZ domain protein CAL interacts with mGluR5a and modulates receptor expression. J Neurochem. 2010;112:588–98.

16. Rezvani K, Baalman K, Teng Y, Mee MP, Dawson SP, Wang H, et al. Proteasomal degradation of the metabotropic glutamate receptor 1α is mediated by Homer-3 via the proteasomal S8 ATPase: signal transduction and synaptic transmission. J Neurochem. 2012;122:24–37.

17. Gulia R, Sharma R, Bhattacharyya S. A critical role for ubiquitination in the endocytosis of glutamate receptors. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:1426–37.

18. Lee JH, Lee J, Choi KY, Hepp R, Lee JY, Lim MK, et al. Calmodulin dynamically regulates the trafficking of the metabotropic glutamate receptor mGluR5. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:12575–80.

19. Citri A, Soler-Llavina G, Bhattacharyya S, Malenka RC. N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor- and metabotropic glutamate receptor-dependent long-term depression are differentially regulated by the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;30:1443–50.

20. Milojevic T, Reiterer V, Stefan E, Korkhov VM, Dorostkar M, Ducza E, et al. The ubiquitin-specific protease Usp4 regulates the cell surface level of the A2A receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69:1083–94.

21. Lee S, Park S, Lee H, Han S, Song JM, Han D, et al. Nedd4 E3 ligase and beta-arrestins regulate ubiquitination, trafficking, and stability of the mGlu7 receptor. Elife. 2019;8:e44502.

22. Kang M, Lee D, Song JM, Park S, Park DH, Lee S, et al. Neddylation is required for presynaptic clustering of mGlu7 and maturation of presynaptic terminals. Exp Mol Med. 2021;53:457–67.

23. Ageta H, Kato A, Hatakeyama S, Nakayama K, Isojima Y, Sujiyama H. Regulation of the level of Vesl-1S/Homer-1a proteins by ubiquitin-proteasome proteolytic system. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:15893–7.

24. Ageta H, Kato A, Fukazawa Y, Inokuchi K, Sugiyama H. Effects of proteasome inhibitors on the synaptic localization of vesl-1S/Homer-1a proteins. Mol Brain Res. 2001;97:186–9.

25. Brakeman PR, Lanahan AA, O’Brien R, Roche K, Barnes CA, Huganir RL, et al. Homer: a protein that selectively binds metabotropic glutamate receptors. Nature. 1997;386:284–8.

26. Tu JC, Xiao B, Yuan JP, Lanahan AA, Leoffert K, Li M, et al. Homer binds a novel proline-rich motif and links group 1 metabotropic glutamate receptors with IP3 receptors. Neuron. 1998;21:717–26.

27. Ango F, Robbe D, Tu JC, Xiao B, Worley PF, Pin JP, et al. Homer-dependent cell surface expression of metabotropic glutamate receptor type 5 in neurons. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2002;20:323–9.

28. Mabb AM, Ehlers MD. Arc ubiquitination in synaptic plasticity. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2018;77:10–6.

29. Hegde AN, Haynes KA, Bach SV, Beckleman BC. Local ubiquitin-proteasome-mediated proteolysis and long-term synaptic plasticity. Front Mol Neurosci. 2014;7:96.

30. Lottes EN, Cox DN. Homeostatic roles of the proteostasis network in dendrites. Front Cell Neurosci. 2020;14:264.

31. Rao VR, Pintchovski SA, Chin J, Peebles CI, Mitra S, Finkbeiner S. AMPA receptors regulate transcription of the plasticity-related immediate-early gene Arc. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:887–95.

32. Greer PL, Hanayama R, Bloodgood BL, Mardinly AR, Lipton DM, Flavell SW, et al. The angelmamn syndrome protein Ube3A regulates synaptic development by ubiquitinating arc. Cell. 2010;140:704–16.

33. Mabb AM, Je HS, Wall MJ, Robinson CG, Larsen RS, Qiang Y, et al. Triad3A regulates synaptic strength by ubiquitination of Arc. Neuron. 2014;82:1299–316.

34. Wall MJ, Collins DR, Chery SL, Allen ZD, Pastuzyn ED, George AJ, et al. The temporal dynamics of Arc expression regulate cognitive flexibility. Neuron. 2018;98:1124–32.

35. Ghane MA, Wei W, Yakout DW, Allen ZD, Miller CL, Dong B, et al. Arc ubiquitination regulates endoplasmic reticulum-mediated Ca2+ release and CaMKII signaling. Front Cell Neurosci. 2023;17:1091324.

36. Bhandare A, Haley M, Anderson VT, Bomingos LB, Lopes M, Correa SA, et al. ArcKR expression modifies synaptic plasticity following epileptic activity: different effects with in vitro and in vivo seizure-induction protocols. Epilepsia. 2024;65:2152–64.

37. Haley M, Bertrand J, Anderson VT, Fuad M, Frenguelli BG, Correa SAL, et al. Arc expression regulates long-term potentiation magnitude and metaplasticity in area CA1 of the hippocampus in ArcKR mice. Eur J Neurosci. 2023;58:4166–80.

38. Briz V, Liu Y, Zhu G, Bi X, Baudry M. A novel form of synaptic plasticity in field CA3 of hippocampus requires GPER1 activation and BDNF release. J Cell Biol. 2015;210:1225–37.

39. Zhang ZY, Bai HH, Guo Z, Li HL, He YT, Duan XL, et al. mGluR5/ERK signaling regulated the phosphorylation and function of glycine receptor α1ins subunit in spinal dorsal horn of mice. PLoS Biol. 2019;17:e3000371.

40. Madsen KL, Beuming T, Niv MY, Chang CW, Dev KK, Weinstein H, et al. Molecular determinants for the complex binding specificity of the PDZ domain in PICK1. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:20539–48.

41. Boudin H, Doan A, Xia J, Shigemoto R, Huganir RL, Worley P, et al. Presynaptic clustering of mGluR7a requires the PICK1 PDZ domain binding site. Neuron. 2000;28:485–97.

42. Dev KK, Nakajima Y, Kitano J, Braithwaite SP, Henley JM, Nakanishi S. PICK1 interacts with and regulates PKC phosphorylation of mGLUR7. J Neurosci. 2000;20:7252–7.

43. EI Far O, Airas J, Wischmeyer E, Nehring RB, Karschin A, Betz H. Interaction of the C-terminal tail region of the metabotropic glutamate receptor 7 with the protein kinase C substrate PICK1. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:4215–21.

44. Perroy J, El Far O, Bertaso F, Pin JP, Betz H, Bockaert J, et al. PICK1 is required for the control of synaptic transmission by the metabotropic glutamate receptor 7. Embo J. 2002;21:2990–9.

45. Enz R, Croci C. Different binding motifs in metabotropic glutamate receptor type 7b for filamin A, protein phosphatase 1C, protein interacting with protein kinase C (PICK) 1 and syntenin allow the formation of multimeric protein complexes. Biochem J. 2003;372:183–91.

46. Suh YH, Pelkey KA, Lavezzari G, Roche PA, Huganir RL, McBain CJ, et al. Corequirement of PICK1 binding and PKC phosphorylation for stable surface expression of the metabotropic glutamate receptor mGluR7. Neuron. 2008;58:736–48.

47. Joch M, Ase AR, Chen CXQ, MacDonald PA, Kontogiannea M, Corera AT, et al. Parkin-mediated monoubiquitination of the PDZ protein PICK1 regulates the activity of acid-sensing ion channels. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:3105–18.

48. Yao I, Takagi H, Ageta H, Kahyo T, Sato S, Hatanaka K, et al. SCRAPPER-dependent ubiquitination of active zone protein RIM1 regulates synaptic vesicle release. Cell 2007;130:943–57.

49. Takagi H, Setou M, Ito S, Yao I. SCRAPPER regulates the thresholds of long-term potentiation/depression, the bidirectional synaptic plasticity in hippocampal CA3-CA1 synapses. Neural Plast. 2012; 352829.

50. Yao I, Takao K, Miyakawa T, Ito S, Setou M. Synaptic E3 ligase SCRAPPER in contextual fear conditioning: extensive behavioral phenotyping of Scrapper heterozygote and overexpressing mutant mice. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17317.

51. Kim CH, Lee J, Lee JY, Roche KW. Metabotropic glutamate receptors: phosphorylation and receptor signaling. J Neurosci Res. 2008;86:1–10.

52. Mao LM, Guo ML, Jin DZ, Fibuch EE, Choe ES, Wang JQ. Post-translational modification biology of glutamate receptors and drug addiction. Front Neuroanat. 2011;5:19.