Abstract

Purpose: Current treatments of urgency urinary incontinence (UUI) are aimed to reduce the neurological influence on bladder detrusor muscle function. A previous observation after posterior exenteration led to the hypothesis that UUI is caused by a laxity of the uterosacral ligaments (USL). In a previous Clinical Phase I trial in patients with UUI continence was achieved in 40% of patients by replacement of the USL. The results supported the concept of a Clinical Phase II trial in which only patients who lost urine after urgency (advanced UI) were treated by replacement of the USL. The aim of the study was to evaluate the cause why some patients became continent while others remained incontinent after replacement of the USL.

Methods: In this Clinical Phase II trial, patients with advanced UI were included. The USL was replaced by specially designed polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) structures. During laparoscopy these structures were fixed at the promontory and at the cervical stump after supracervical hysterectomy (cervicosacropexy, CESA) or at the vaginal stump (vaginosacropexy, VASA). The USL replacing parts of the structures had an identical length of 8.8 cm in CESA and 9.3 cm in VASA. Patients who remained incontinent after tensioning of the vagina were offered a suburethral trans-obturator tape (TOT).

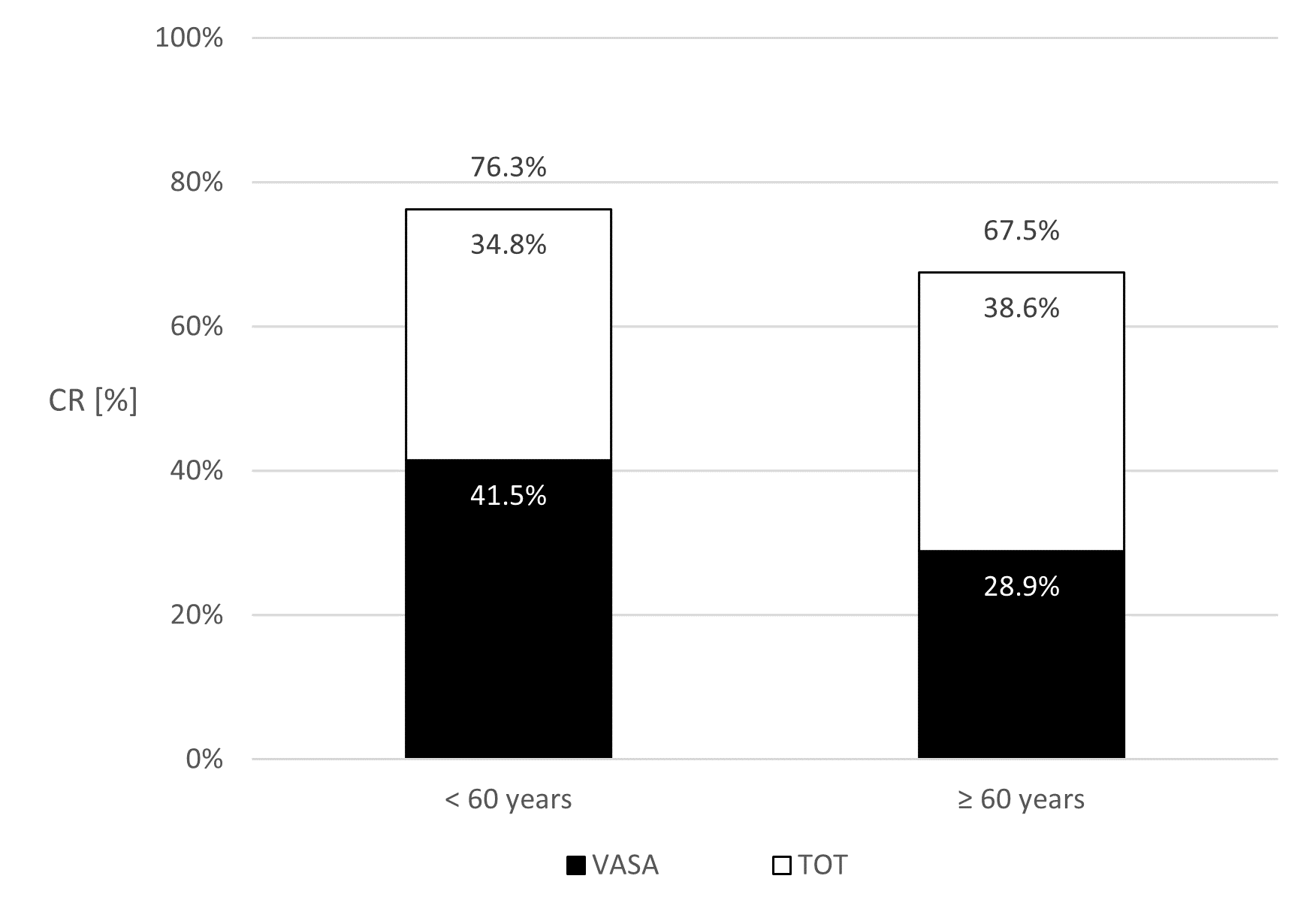

Results: 339 patients with advanced urinary incontinence (UI) were evaluable. Continence was re-established in 39% of patients after CESA and in 32.9% after VASA. The statistical analysis revealed that the Continence Rates (CR) after CESA or VASA were significantly (p<0.001) dependent on patients age at surgery (<60 years vs ≥60 years). The respective CR after CESA were 50% vs 26% and after VASA 41.5% vs 28.9%. After an additional transobturator tape (TOT) the overall CR was between 67.5% and 87.5%.

Conclusion: The replacement of the USL by PVDF-tapes of defined length led to continence in between 32.9% and 39% of the patients. After the additional placement of a TOT 8/4 the percentage of continent patients increased by 30.5% to 37.3%. These findings support the hypothesis that continence is dependent on the physiological function of the USL and PUL. The observation that the CR after USL replacement decreased in patients ≥60 years indicates that ageing affected some additional other part in the area of the urethra-vesical junction (UVJ). The CR after CESA or VASA (and a TOT) in patients with advanced UI deserve further clinical evaluation.

Keywords

Urgency urinary incontinence, CESA, VASA, TOT 8/4, Age dependence

Introduction of the Study

Urinary incontinence (UI) in women is described by symptoms. Urine loss after coughing or sneezing or other physical activities which increase the pressure on the bladder is summarized as stress urinary incontinence (SUI). Another group of patients experiences incontinence with a preceding feeling of urgency. That form of incontinence was therefore named urgency urinary incontinence (UUI). The term UUI covers a wide range of symptoms. The subjective feeling of urgency to void leads to frequent voiding sometimes without loss of urine sometimes with incontinence. Nowadays treatments focus on symptom improvement. That can be achieved in a considerable number of patients; however, if UUI is associated with incontinence medical treatment cannot lead to definitive continence [1-5]. That stage of development is what was summarized under the term “advanced urinary incontinence (UI)”.

In 1996 an incidental finding in treatment of advanced cancer of the uterus led us to hypothesize that UUI is based on a reduced tension of the anterior vaginal wall suspending the bladder in the area of the urethra-vesical junction (UVJ). At that time uterine cancer invading the rectum was treated with resection of the uterus, ovaries, and rectum (posterior exenteration). A sigma anus praeter was placed. Unlike as in complete exenteration, the bladder and underlying vagina remained in situ. After surgery the small pelvis was irradiated [6].

However, severe radiation side effects especially of the small bowel (radiation colitis) often necessitated interrupting or even discontinuing treatment [7]. Since pelvic irradiation was an integral part of management after exenteration, ways were sought to prevent the small bowel from radiation. It was decided to close the small pelvis with a mesh to prevent bowel prolapse into the field of radiation.

A Goretex® mesh was sutured with one side at the promontory. At the other side the apical end of the vagina was sutured. Therefore, the vagina had to be elevated and stretched. Six months after radiation therapy, the mesh should be removed and the sigmoid re-anastomosed to the anus.

At follow-up, several patients who were incontinent before surgery reported that they were continent again immediately after surgery. Before the posterior exenteration these patients had experienced years of "constant" urine leakage and most of them needed to wear diapers all day. Since they were told that this stage of UUI was incurable they were more astonished that they were continent again after exenteration.

When they were offered the removal of the mesh and re-anastomosis of the sigma colon to reverse the anus praeter, patients refused that operation. They prioritized their new continence - even with an anus praeter [8].

Since continence after posterior exenteration had never been observed or reported before it was hypothesized that the tight tensioning and elevation of the vagina by the mesh was the reason for continence. As counter-hypothesis it was assumed that UUI was caused by a reduced tension of the vagina. That hypothesis was difficult to accept because it was in contrast to the prevailing hypothesis that UUI was a neurological disorder leading to an overactivity of the detrusor vesicae muscle [9,10].

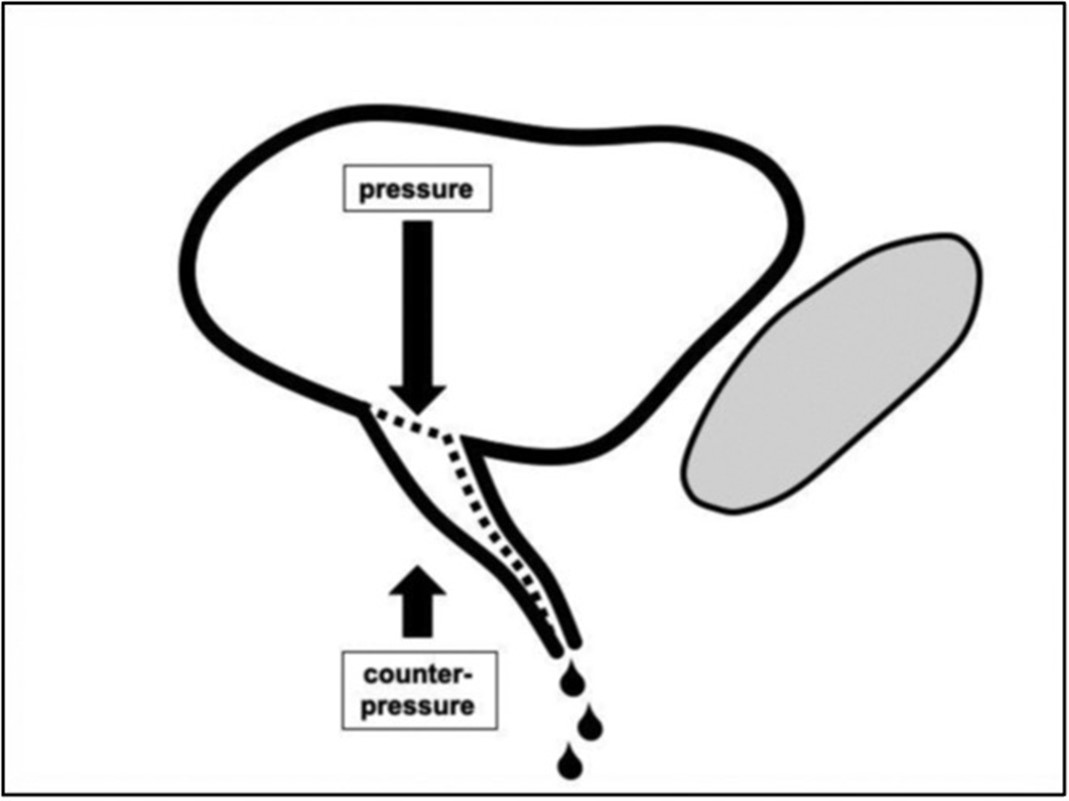

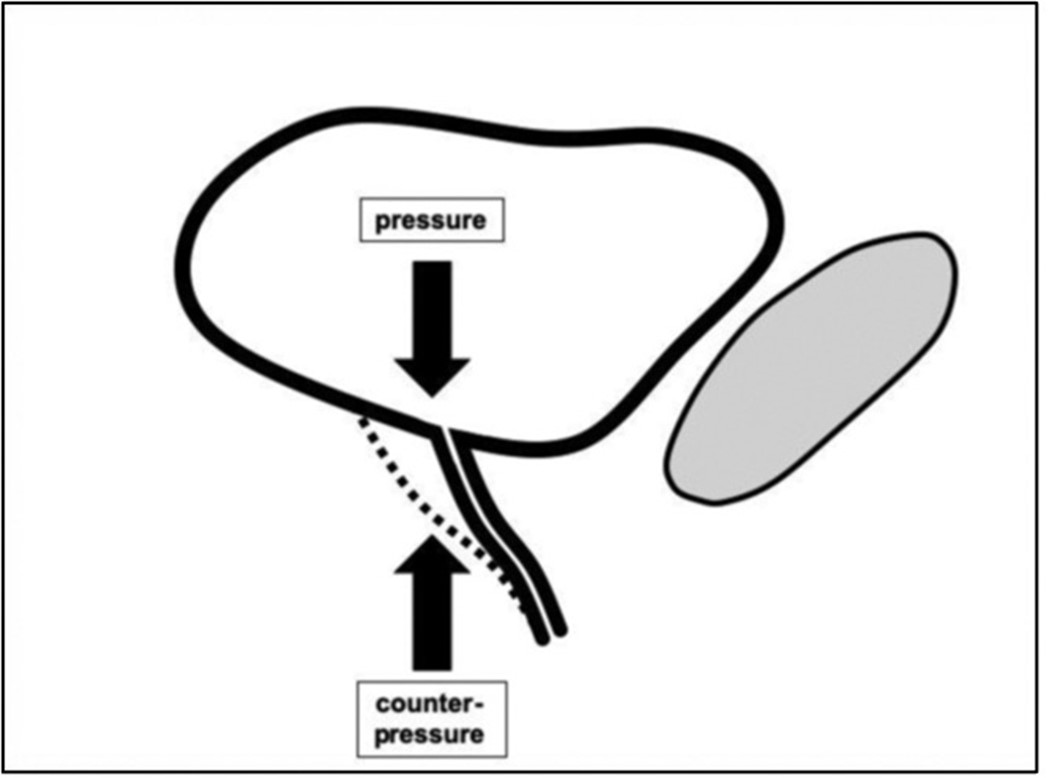

In 1993, Petros and Ulmsten had presented the "Integral Theory" proposing that SUI as well as UUI were based on an impaired function (“laxity”) of the pubo-urethral and utero-sacral ligaments. Continence is based on the balance between the pressure of a filled bladder and the counterpressure exerted by the vagina at the urethra-vesical junction (UVJ) [11,12]. The UVJ is anatomically located above the middle of the vagina. According to the Integral Theory "laxity" of the pubourethral ligaments (PUL) diminish the counterpressure in the lower part of the UVJ and laxity of the uterosacral ligaments (USL) the counterpressure in the upper part of the UVJ. According to the prevailing laxity of the PUL and/or the USL different symptoms of UI can appear (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Hypothetical anatomical cause of UI. The pressure of the full bladder will open the bladder outlet (UVJ) leading to incontinence when the area below the bladder outlet does not exert enough counterpressure.

The first clinical implementation of the “Integral Theory” was the replacement of the “lax” PUL by different tapes to increase counterpressure at the lower UVJ during coughing and sneezing. This approach turned out to be highly effective in restoring continence and became standard treatment for SUI [13].

Consequently, the effect of suburethral tapes was also studied in patients with UUI. In some patients continence was achieved, however, it failed in most patients [3,13]. These results, coupled with the (neurological) symptom of urgency before the loss of urine led to the belief that UUI was not based on anatomical changes but has a different neurological etiology requiring neurological treatment [9,10].

Therefore, the second aspect of the Integral Theory - the importance of the bilateral suspension of the vagina by the PUL and the uterosacral ligaments (USL) - was not pursued clinically. Our observations, however, supported the importance of intact USL so that it was decided to develop a technique for the surgical replacement of the USL [14-16]. To ensure reproducibility of the results a surgical procedure had to be developed which every surgeon could do in exactly the same way [17].

In a first randomized clinical trial (URGE 1) CESA or VASA were compared with the established parasympathomimetic medication in patients with UUI. The study had to be stopped at the intermediate analysis. Patients with medication reported a reduction of urgency symptoms but none of them became continent. However, 4 out of 10 patients who were operated by CESA or VASA became continent [23]. Therefore, the surgical approach for treatment of UUI was approved for further clinical trials [8]. In this Clinical Phase II trial, the outcome after replacement of the USL should be categorized as continent or incontinent and the reasons for remaining incontinent should be evaluated. It was recommended to start the clinical evaluation in patients who had failed previously established treatments.

Material and Methods

The presented study was a Clinical Phase II trial. In this clinical trial the hypothesis was tested that advanced urinary continence as a stage of UUI is based on an impaired function of the USL.

Inclusion criteria

Patients were included who reported involuntary loss of urine before reaching the toilet after the feeling of urgency (“advanced urinary incontinence”). According to the current definition, they had UUI as they experienced involuntary loss of urine after the urgency to go to the toilet. Patients had to give informed consent at first presentation at the clinic and at the examination before surgery.

Exclusion criteria

Patients with any type of cancer, previous incontinence surgery, colporrhaphy, or colposuspension were excluded. A previous trans-obturator tape (TOT) or tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) was also an exclusion criterion.

All procedures adhered to the Standards of International Clinical Trials with approval of the Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of the University of Köln, Germany. The current analysis was approved by the same Committee (No 20-1267).

Symptoms of UUI

Symptoms were recorded on the basis of established questionnaires. In most of these questionnaires several answer possibilities were offered for one question. The questionnaires were designed to detect improvements of symptoms.

The outcome variable of that Clinical Trial was “continent” or “incontinent”. For the statistical analysis of that Clinical Trial only dichotomous parameters were used. Therefore, the different answer possibilities of the questionnaires were summarized in two possibilities which then could be classified as continent or incontinent. For the definition of urinary incontinence (UI) the questionnaire of the International Continence Society (ICS) was used [24]. The definition of UUI was based on the question of how patients react on the feeling of urgency while watching the news on TV. Two groups were separated: those who went to the toilet immediately after the urgency and those who could wait until the weather forecast or even longer before they go to the toilet.

Patients who went to the toilet immediately were asked if they had experienced involuntary loss of urine on the way to the toilet. Patients who did not lose urine after the urgency were categorized as “overactive bladder” (UUI but continent). Patients who lost urine after urgency were categorized as patients with “advanced urinary incontinence”.

Some patients reported at their initial presentation that they could reach the toilet "dry" if they went immediately after the urgency to urinate. During that phase most of the patients also leaked urine when coughing or sneezing. They were initially categorized as having mixed urinary incontinence (MUI). However, after some time (COVID break), the same patients reported leaking urine already on the way to the toilet. Therefore, the group of MUI patients were merged into the overall UUI group and categorized as patients with advanced UI.

The follow-up examinations were scheduled at 4 and 12 weeks after CESA or VASA. The questionnaires were answered together at the first presentation as well as during the follow-up examinations. The answers were always documented in a computer data bank.

After surgery patients who did not have any problem with the uncontrolled loss of urine after urgency were defined as “continent after surgery”. After urgency they continued watching TV until the forecast and even longer and did not lose urine on the way to the toilet.

Patients who were continent after CESA or VASA did not require further treatment. Patients who remained incontinent after CESA or VASA were offered an additional TOT [22]. The follow-up examination was scheduled at 4 weeks after TOT.

Surgery

In order to make the results reproducible the surgical methods to replace the USL (CESA or VASA) and the placement of the TOT were standardized.

CESA and VASA

In order to evaluate factors which influenced the outcome of CESA or VASA in terms of continence it was necessary to perform the vaginosacropexy and the uterosacropexy as identical as possible in all patients.

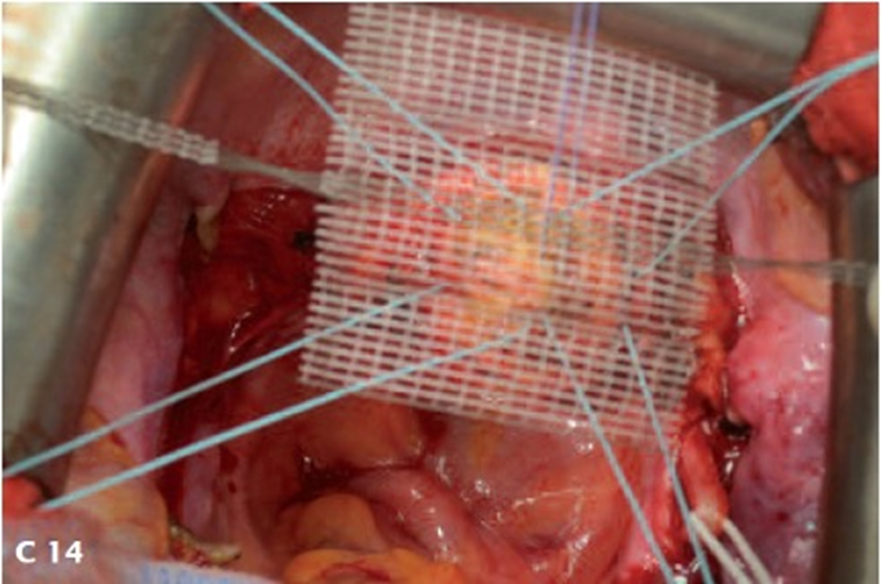

The length of the USL was not found in anatomical textbooks; therefore, it was measured during surgery in patients without clinical prolapse of the uterus. The USL had a measurable length of 9 ± 0.2 cm. Therefore, the length of the USL replacing structures was decided to be 8.8 cm in CESA and 9.3 cm in VASA. The longer arms in VASA structures were based on the consideration that the remaining cervical stump after supracervical hysterectomy at the level of the peritoneal fold of the USL was 0.5 cm. Furthermore, the fixation sides at the promontory and at the vagina or cervix were clearly defined anatomically and technically with marks on the structures. That standardization led to a great homogeneity of the placement of the CESA and VASA (and TOT) structures among different surgeons [14,17].

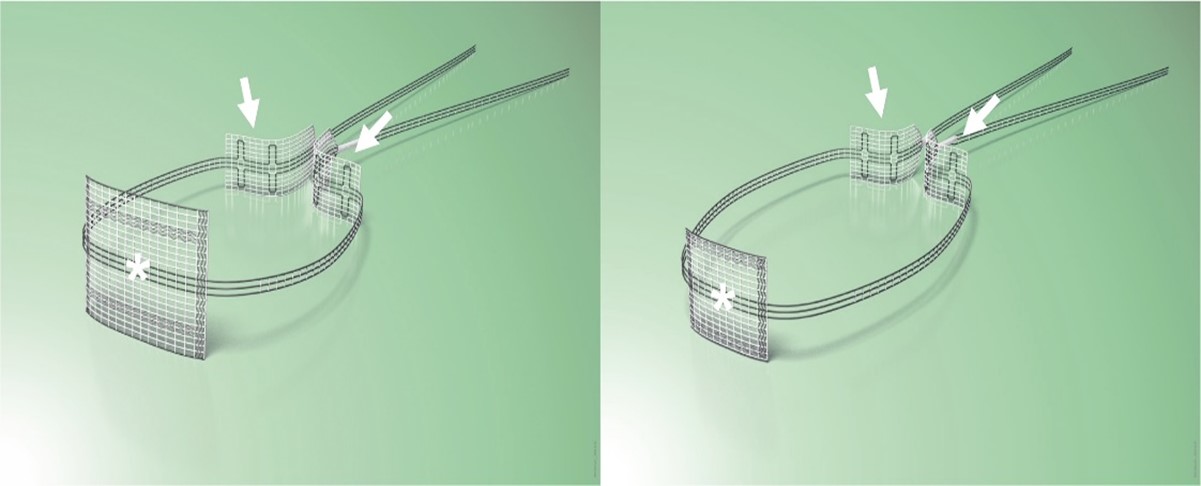

The surgical replacement of the uterosacral ligaments (USL) could be standardized for all women in the same way due to the consistent dimensions of the female bony pelvis and length of the vagina [18]. Because the USL are bilateral (on both sides of the pelvis), the Dynamesh CESA/VASA structures were designed with two "arms" [19-21].

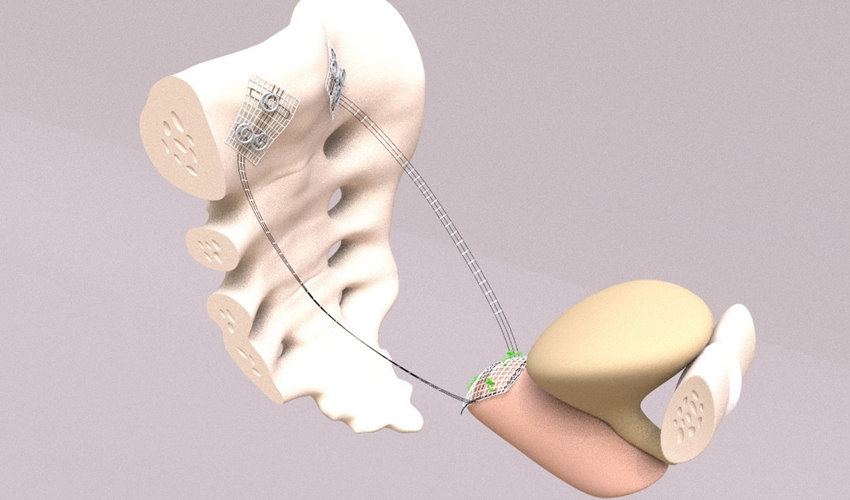

Up to 2014, the tapes were placed during laparotomy. Since 2014, CESA and VASA have been performed laparoscopically (laCESA, laVASA) [21,25]. Based on recommendations of the Institute for Sustainable Textiles (RWTH University Aachen, Germany), polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) was used to develop the ligament structures. Two fixation sides for fixation at either the vaginal or cervical stump (after supracervical hysterectomy) and the promontory were connected with the PVDF tapes ("arms") serving as the replacement for the natural USL (DYNAMESH CESA, DYNAMESH VASA, Dahlhausen, Köln, Germany) (Figure 2). The structures can be detected in the body by magnetic resonance tomography (MRT).

Figure 2. CESA and VASA structures. The arrows point to the suture sides on the sacral bone. The anterior part with the asterisk is fixed either on the cervix (left photo) or on the vaginal stump (right photo). Thereafter, the “arms” of the structure replacing the USL – the part between the fixation sides - are pulled through the peritoneal fold of the USL towards promontory. The CESA ligament is 0.5 cm shorter than the VASA ligament.

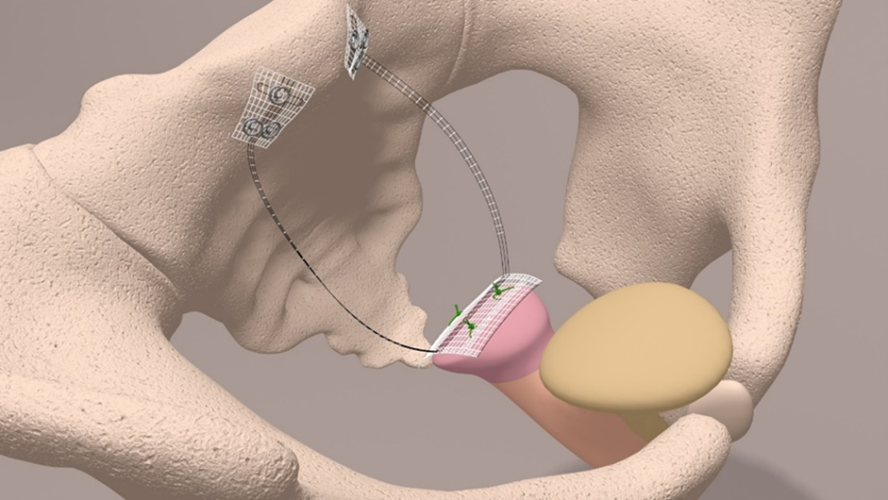

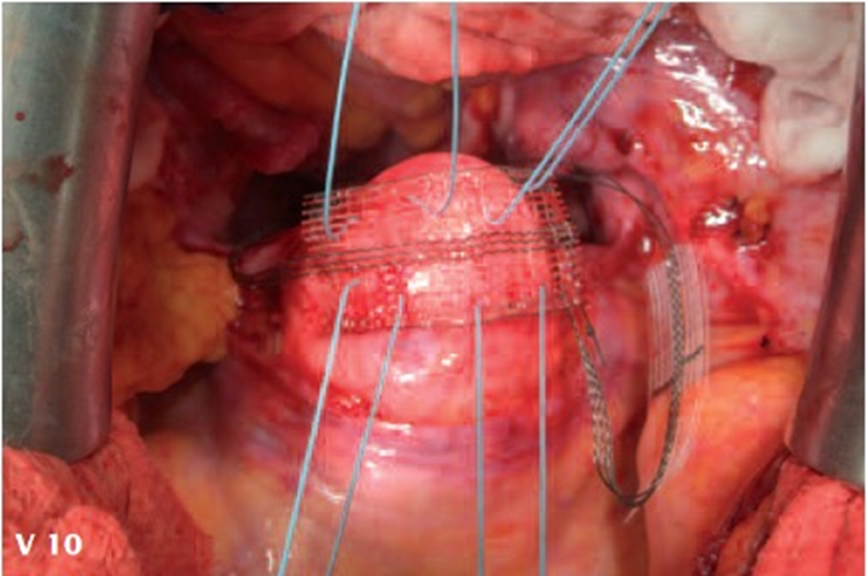

The PVDF structures were fixed at either the cervical stump (CESA) or the vaginal stump (VASA) and pulled through the peritoneal fold of the USL to the promontory, ensuring consistent tension and elevation of the vagina [8,21] (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3. Schematic drawing of the CESA (upper part) and surgical fixation of the CESA structure on the cervical stump (lower part).

Figure 4. Schematic drawing of the VASA (upper part) and surgical fixation of the VASA structure on the vaginal stump. A plastic phantom is placed in the vagina for suturing (lower part) the structure to the vagina.

TOT 8/4

Patients who remained incontinent after CESA or VASA were offered an additional suburethral trans-obturator tape (TOT). In order to achieve an identical “tension-free” placement of the suburethral tape in all patients the placement was also standardized. In the OT a Hegar pin (size 8) was put into the urethra and another Hegar pin (size 4) below the urethra to establish a “tension-free” placement (TOT 8/4). After placement and tensioning of the tape the Hegar pins were removed [22].

Statistical methods

For the descriptive analysis the constant variable of patients “age at surgery” was tested for normal distribution using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. If a normal distribution was given the constant variables of mean (m) and standard deviation (sd) were used as measure. If the data were not normally distributed the median (md) and the Interquartile difference (IQR) between Q3-Q1 were determined.

This study was focused on the descriptive analyses of the target variable “continence” as well as of the influencing variables “age at surgery” and “kind of surgery (CESA or VASA)”. Age at surgery was subdivided in patients <60 years and ≥ 60 years. These categorial variables were given in absolute and relative percentage. The distribution according to the kind of surgery was dichotomous. Therefore, the comparison of the patients who were operated by CESA or VASA were unconnected samples.

To test significant differences of the categorial variables the Χ² test was applied for univariate analysis of significance. If the sample size (n) was <5 or <20 patients, Fisher´s exact test was applied. The level of significance α was defined at 0.05 therefore p<0.05 was significant. The influence of the variables age at surgery and kind of surgery on the target variable continence was tested by a multivariate binary logistic regression.

All clinical data and the answers to the questionnaires were recorded during the presentation at the clinic. For calculations the IBM SPSS Statistics Program (version 26) was used. All calculations were performed at the Institute for Medical Statistics and Bioinformatics, University of Köln, Germany.

The Clinical Trial was approved by the Scientific Committee of the University of Köln and the Ethic Committee of the University of Köln (approval number: TN 20-1267). The current analysis was approved on June 29th, 2022 (nr.20-2312).

Results

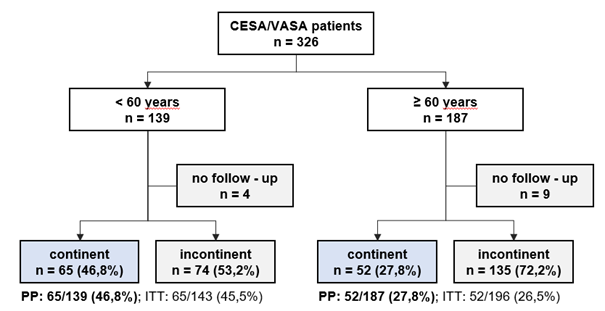

In the time interval between 2010 and 2022, 369 patients fulfilled the study inclusion criteria. 30 patients were lost for follow-up leaving 339 evaluable patients with advanced UI. A total of 159 patients underwent CESA, and 167 patients underwent VASA (Figure 5 and Table 1).

Figure 5. Overall clinical outcome after CESA or VASA separated to patients age at surgery.

|

Statistical evaluation of different variants |

Significance (p) |

Number (n) |

|

CR after CESA / VASA |

0.254 |

326 |

|

CR <60 years / ≥ 60 years |

≤0.001 |

326 |

|

CR CESA <60 years / CESA ≥ 60 years |

0.002 |

159 |

|

CR VASA <60 years / CESA ≥ 60 years |

0.108 |

167 |

|

CR CESA + TOT / VASA + TOT |

0.762 |

107 |

|

CR TOT <60 years / CESA ≥ 60 years |

0.110 |

107 |

|

CR CESA + TOT <60 years / CESA ≥60 years |

0.019* |

47 |

|

CR VASA + TOT <60 years / CESA ≥60 years |

0.969 |

60 |

The mean age of the CESA group was 58.6 years (sd ±12.1 years). The mean age of the VASA group was 65 years (sd ±10.7 years). The percentage of patients who were continent after surgery were reported as Continence Rate (CR). The CR was 39% after CESA and 32.9% after VASA (p=0.25).

The CESA group included 86 patients younger than 60 years (54.1%) and 73 patients older than 60 years (45.9%). The VASA group included 53 patients younger than 60 years (31.7%) and 114 patients older than 60 years (68.3%).

After dividing patients into two age groups, the results for CESA and VASA showed a remarkable difference which were statistically significant different in the CESA group (p<0.001).

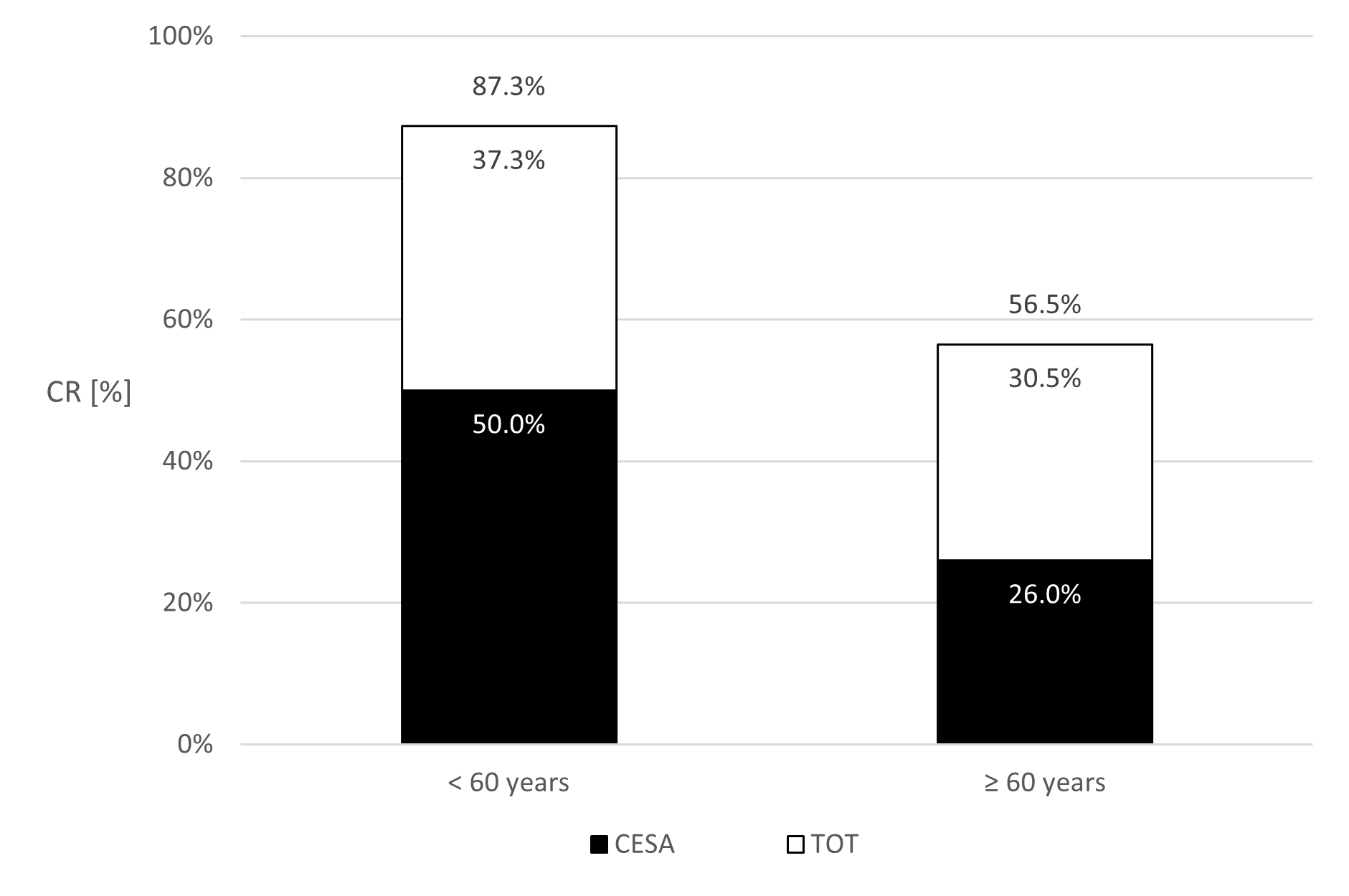

Among patients younger than 60 years, 43 out of 85 (CR: 50%) achieved continence after CESA, compared to 22 out of 51 patients (CR: 26%) older than 60 years (p = 0.002) (Figure 6).

For VASA, 22 out of 53 patients (CR: 41.5%) younger than 60 years achieved continence. In the group of patients older than 60 years, 33 out of 114 patients (CR: 28.9%) achieved continence (p = 0.11) (Figure 7).

Patients who remained incontinent after CESA or VASA typically reported no noticeable surgical effect. They stated that "nothing has changed." Based on prior experiences, they were then offered a TOT 8/4 [8]. Following TOT 8/4 additionally 30.5% to 37.3% of the incontinent patients after CESA or VASA became continent (Figures 6 and 7).

The overall CR in the younger age group (<60 years) was 87.3% for CESA and TOT 8/4 and 76.3% for VASA and TOT (p=0.76).

The respective overall CR for patients older than 60 years was 56.5% for CESA and TOT 8/4 and 67% for VASA (p=0.68) (Figures 5 and 6).

Figure 6. Percentage of patients who became continent (Continence rates (CR)) after cervicosacropexy (CESA) alone and after an additional transobturator tape (TOT). The columns present the CR of patients younger than 60 years at CESA (left) or older than 60 years (right).

Figure 7. Percentage of patients who became continent (Continence rates (CR)) after vaginosacropexy (VASA) alone and after an additional transobturator tape (TOT). The columns present the CR of patients younger than 60 years at CESA (left) or older than 60 years (right).

Discussion

This Clinical Phase II trial investigated the hypothesis that advanced UI was caused by a diminished tension of the vagina caused by an impaired function of the USL. Therefore, the USL was replaced by standardized PVDF structures of identical length in CESA or VASA [14,26]. Based on previous studies it was furthermore tested if the additional replacement of the PUL can lead to continence in these patients when the USL had been replaced but the patient remained incontinent [8,14,23].

The great advantage of that Clinical Trial compared to other studies was its homogeneity of symptoms and treatment. All patients had the same symptoms of urinary incontinence, and all patients got the identical surgical treatment.

At the first presentation all patients reported a continuous development leading to advanced UI. It started as urine loss when coughing or sneezing and continued after several years with the development of urinary incontinence after urgency. In the beginning of UUI they could reach the toilet “dry”, however, that usually developed to the stage when they lost urine already on the way to the toilet (advanced UI).

The standardization of CESA, VASA, and TOT was possible because of the nearly identical pelvic dimensions in women. Thereby, the standardized procedures ensured consistency across surgeons and facilitated statistical analysis to identify factors influencing continence outcomes.

The replacement of the USL led to continence rates of 39% (CESA) and 32.9% (VASA) for the respective patients. If both ligaments were replaced continence was achieved in between 67% and 87% of patients.

The statistically most important factor to achieve continence was the age of the patients at surgery. Higher CR was achieved in younger patients (<60 years) compared to older patients. For the younger patients the CR after CESA was 50% and after VASA 41.5%. In patients ≥ 60 years the CR was remarkably less (26% for CESA and 28.9% for VASA).

The additional placement of a TOT 8/4 after CESA or VASA led to continence in another 30.5%-37.3% of the incontinent women, resulting in overall CR between 67% and 87%. These remarkable results were recently confirmed by several other clinical studies [25-29].

Interestingly, the age at surgery did not affect the outcome after TOT. That needs to be interpreted with caution since all these patients with a secondary TOT already had a tensioning of the vagina by the previous CESA or VASA [30].

In 2022, a Clinical Phase I Trial was based on the fact that 30.5% to 37% of patients became continent after the TOT 8/4 (after CESA or VASA). Since a TOT is physically less stressful as CESA or VASA it was proposed to patients >60 years to start treatment by placing a TOT. If patients remain incontinent laCESA or laVASA would be the second step. It was hypothesized that 3 out of the first 10 patients were continent after the TOT 8/4. However, after the first 12 patients none became continent after the TOT 8/4. Therefore, the study was stopped according to the protocol. The conclusions drawn from these results were that a TOT can only be efficient for treatment of UI when the vagina has still its normal tension.

Continence is maintained by a delicate balance between bladder pressure and counterpressure exerted by the vagina at the urethrovesical junction (UVJ) (Figure 8). The UVJ is placed in the anatomical trigone of the bladder [12]. Increasing bladder volume or physical activity leads to an increasing pressure on the UVJ. Conversely, lying down reduces the pressure on the UVJ. Similarly, patients sitting on chairs or saddles experience sufficient counterpressure to remain continent. However, upon standing, counterpressure may become insufficient, leading to urine loss.

Figure 8. Hypothetical anatomical cause of UI. The pressure of the full bladder will open the bladder outlet (UVJ) leading to incontinence when the area below the bladder outlet does not exert enough counterpressure. The aim of surgical treatment is to increase the counterpressure by narrowing the UVJ (lower drawing). That is achieved in the urethral part by a suburethral tape and in the vaginal part by tensioning of the vagina.

While Petros and Ulmsten stressed the important intra-bladder zone of the UVJ as important for incontinence Delancey assumed that the tissue under the UVJ (“hammock”) is responsible for continence [11,12].

It can be assumed that the tensioning and elevation of the vagina by CESEA or VASA puts the UVJ out of the zone of maximum pressure and/or increases the counterpressure (hammock). In some patients the elevation of the upper part of the UVJ by CESA or VASA already led to continence. In the remaining patients the lower part was also affected and needed stabilization by a TOT.

This study highlights the crucial role of the USL and the PUL in maintaining continence. We assume that the extent of laxity at the UVJ determines the severity of incontinence. A compromised PUL primarily leads to leakage under high pressure (e.g. coughing), while a dysfunctional USL can cause leakage already at lower pressures (e.g. standing up). When the patient loses urine under any condition probably both parts of the UVJ are affected. That leads to the conclusion that both ligaments need repair. However, the study demonstrated that even after repair of both ligaments several patients remained incontinent.

The observation of a lower CR in elderly patients cannot be caused by the USL since they were all replaced with structures of the same length.

The progression of incontinence symptoms is gradual. The observed continuous progression of incontinence from SUI to UUI with ageing is accompanied by anatomical changes of the vagina and the respective connective tissue [31]. Based on the results of replacement of the USL and PUL, urgency UI must be caused by additional changes in the area of the UVJ.

Since not every woman develops UI a genetical predisposal can be hypothesized which is stressed by the fact that 97% of the patients with UI reported a family history [32]. In correlation to the clinical course of urinary incontinence both SUI and UUI may represent different stages of the same underlying condition [32,33].

The precise etiology of UI remains elusive. However, the surgical replacements of the USL and the PUL can help most of these patients to become continent again.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that surgical repair of the USL and the suburethral PUL can lead to continence in most of the patients suffering from advanced UI. This study underscores the critical role of age - especially ≥ 60 years - and the aging process for both the development and treatment of UI. While the specific factors influencing the pathogenesis of UI remain unclear, age demonstrably impacts the outcomes of surgical USL replacement. The study further suggests a potential common etiology for SUI and UUI, with the progression of symptoms highlighting a gradual worsening of the underlying condition. Future research should focus on elucidating the definitive etiology of UI and exploring the potential impact of genetic alterations for the development of urinary incontinence.

Conflicts of Interest

W. Jäger receives royalties from the FEG in Aachen. All other authors have no conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

This study was not financially supported.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank S.Ludwig and R.Morgenstern for the development and performance of the laparoscopical CESA (laCESA) and VASA (laVASA). Without their skills and intellectual approach, the development of the procedures and the development of new surgical equipment would have been impossible.

The authors further thank E. Neumann for the continuous data documentation during the whole study. She had always open ears for the patient’s wishes and problems and helped them whenever she could.

References

2. Balk E, Adam GP, Kimmel H, Rofeberg V, Saeed I, Jeppson P, et al. Nonsurgical Treatments for Urinary Incontinence in Women: A Systematic Review Update [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2018 Aug. Report No.: 18-EHC016-EFReport No.: 2018-SR-03.

3. Shin JH, Choo MS. De novo or resolved urgency and urgency urinary incontinence after midurethral sling operations: How can we properly counsel our patients? Investig Clin Urol. 2019 Sep;60(5):373-79.

4. Coolen RL, Groen J, Blok B. Electrical stimulation in the treatment of bladder dysfunction: technology update. Med Devices (Auckl). 2019 Sep 11;12:337-45.

5. Polat S, Yonguc T, Yarimoglu S, Bozkurt IH, Sefik E, Degirmenci T. Effects of the transobturator tape procedure on overactive bladder symptoms and quality of life: a prospective study. Int Braz J Urol. 2019 Nov-Dec;45(6):1186-95.

6. Bacalbasa N, Balescu I, Vilcu M, Neacsu A, Dima S, Croitoru A, et al. Pelvic Exenteration for Locally Advanced and Relapsed Pelvic Malignancies - An Analysis of 100 Cases. In Vivo. 2019 Nov-Dec;33(6):2205-10.

7. Sapienza LG, Salcedo MP, Ning MS, Jhingran A, Klopp AH, Calsavara VF, et al. Pelvic Insufficiency Fractures After External Beam Radiation Therapy for Gynecologic Cancers: A Meta-analysis and Meta-regression of 3929 Patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2020 Mar 1;106(3):475-84.

8. Jäger W, Mirenska O, Brügge S. Surgical treatment of mixed and urge urinary incontinence in women. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2012;74(2):157-64.

9. Chen LC, Kuo HC. Pathophysiology of refractory overactive bladder. Low Urin Tract Symptoms. 2019 Sep;11(4):177-81.

10. Steers WD (2002): Pathophysiology of overactive bladder and urge urinary incontinence. Rev Urol.4 Suppl 4(Suppl 4):S7-S18. PMID: 16986023; PMCID: PMC1476015.

11. Petros PE, Ulmsten UI (1993): An integral theory and its method for the diagnosis and management of female urinary incontinence. Scand J Urol Nephrol Suppl. 153:1-93.

12. DeLancey JO. Structural support of the urethra as it relates to stress urinary incontinence: the hammock hypothesis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994 Jun;170(6):1713-20; discussion 1720-3.

13. Delorme E. La bandelette trans-obturatrice: un procédé mini-invasif pour traiter l’incontinence urinaire d’effort de la femme. Prog Urol. 2001 Dec;11(6):1306-13.

14. Jäger W, Brakat A, Ludwig S, Mallmann P. Effects of the apical suspension of the upper vagina by cervicosacropexy or vaginosacropexy on stress and mixed urinary incontinence. Pelviperineology. 2021 Mar 1;40(1):32-8.

15. Petros P. Function, Dysfunction and Management According to the Integral Theory. In: The female pelvic floor: Function, dysfunction and management according to the integral theory. Third Edition. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2010.

16. Ludwig S, Göktepe S, Mallmann P, Jäger W. Evaluation of Different 'Tensioning' of Apical Suspension in Women Undergoing Surgery for Prolapse and Urinary Incontinence. In Vivo. 2020 May-Jun;34(3):1371-5.

17. Stark M, Gerli S, Di Renzo GC. The importance of analyzing and standardizing surgical methods. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2009 Mar-Apr;16(2):122-5.

18. Hsu Y, Chen L, Summers A, Ashton-Miller JA, DeLancey JO. Anterior vaginal wall length and degree of anterior compartment prolapse seen on dynamic MRI. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008 Jan;19(1):137-42.

19. Chen L, Ramanah R, Hsu Y, Ashton-Miller JA, Delancey JO. Cardinal and deep uterosacral ligament lines of action: MRI based 3D technique development and preliminary findings in normal women. Int Urogynecol J. 2013 Jan;24(1):37-45.

20. DeLancey JO. Anatomic aspects of vaginal eversion after hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992 Jun;166(6 Pt 1):1717-24; discussion 1724-8.

21. Ludwig S, Morgenstern B, Mallmann P, Jäger W. Laparoscopic bilateral cervicosacropexy: introduction to a new tunneling technique. Int Urogynecol J. 2019 Jul;30(7):1215-7.

22. Ludwig S, Stumm M, Mallmann P, Jager W. TOT 8/4: A Way to Standardize the Surgical Procedure of a Transobturator Tape. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:4941304.

23. Ludwig S, Becker I, Mallmann P, Jäger W. Comparison of Solifenacin and Bilateral Apical Fixation in the Treatment of Mixed and Urgency Urinary Incontinence in Women: URGE 1 Study, A Randomized Clinical Trial. In Vivo. 2019 Nov-Dec;33(6):1949-57.

24. Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, Griffiths D, Rosier P, Ulmsten U, et al. Standardisation Sub-Committee of the International Continence Society. The standardisation of terminology in lower urinary tract function: report from the standardisation sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Urology. 2003 Jan;61(1):37-49.

25. Rexhepi S, Rexhepi E, Stumm M, Mallmann P, Ludwig S. Laparoscopic Bilateral Cervicosacropexy and Vaginosacropexy: New Surgical Treatment Option in Women with Pelvic Organ Prolapse and Urinary Incontinence. J Endourol. 2018 Nov;32(11):1058-64.

26. Jaeger W, Ludwig S, Stumm M, Mallmann P. Standardized bilateral mesh supported uterosacral ligament replacement–cervico-sacropexy (CESA) and vagino-sacropexy (VASA) operations for female genital prolapse. Pelviperineology. 2016 Mar 1;35(1):17-21.

27. Joukhadar R, Baum S, Radosa J, Gerlinger C, Hamza A, Juhasz-Böss I, et al. Safety and perioperative morbidity of laparoscopic sacropexy: a systematic analysis and a comparison with laparoscopic hysterectomy. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2017 Mar;295(3):641-9.

28. Rajshekhar S, Mukhopadhyay S, Morris E. Early safety and efficacy outcomes of a novel technique of sacrocolpopexy for the treatment of apical prolapse. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2016 Nov;135(2):182-6.

29. Page AS, Page G, Deprest J. Cervicosacropexy or vaginosacropexy for urinary incontinence and apical prolapse: A systematic review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2022 Dec;279:60-71.

30. de Boer TA, Slieker-ten Hove MC, Burger CW, Vierhout ME. The prevalence and risk factors of overactive bladder symptoms and its relation to pelvic organ prolapse symptoms in a general female population. Int Urogynecol J. 2011 May;22(5):569-75.

31. Portman DJ, Gass ML; Vulvovaginal Atrophy Terminology Consensus Conference Panel. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: new terminology for vulvovaginal atrophy from the International Society for the Study of Women's Sexual Health and the North American Menopause Society. J Sex Med. 2014 Dec;11(12):2865-72.

32. Jäger W, Ludwig S, Neumann E, Mallmann P. Evidence of Common Pathophysiology Between Stress and Urgency Urinary Incontinence in Women. In Vivo. 2020 Sep-Oct;34(5):2927-32.

33. Ludwig S, Stumm M, Neumann E, Becker I, Jäger W. Surgical treatment of urgency urinary incontinence, OAB (wet), mixed urinary incontinence, and total incontinence by cervicosacropexy or vaginosacropexy. Gynecol Obstet. 2016;6(9):404-8.