Abstract

Background: Chikungunya arthritis is a chronic condition characterized by persistent joint pain following an infection with the Chikungunya virus (CHIKV), transmitted by Aedes mosquitoes. This study aims to identify commonly used medicinal plants for post-chikungunya rheumatism in Amazonas, Brazil, and examine beliefs and usage patterns.

Methods: This observational study was conducted between May and September 2023 in Roraima, Amazonas, Brazil. Adult participants with a history of CHIKV infection were recruited and interviewed using a structured questionnaire. Data was obtained on demographics, CHIKV infection details, arthritis severity measured using the Disease Activity Score-28 (DAS-28), and the use of medicinal plants for symptom management.

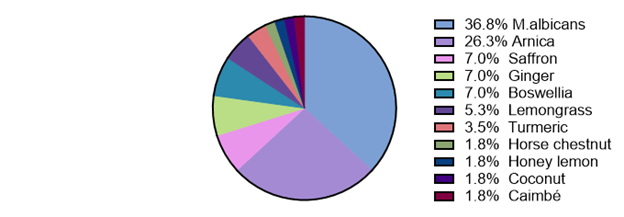

Results: A total of 47 participants (mean age: 40.6 years, 59.6% female) with a history of CHIKV infection and arthralgia were included in this study. The majority (78.7%) reported using at least one common medicinal plant for symptom relief: Miconia Albicans (36.8%) and Arnica (26.3%) being the most common, followed by Boswellia, Saffron, Ginger, Lemongrass, and Turmeric (7% each). Less commonly, Caimbé, Coconut, Lemon & Honey, Horse Chestnut, and Capim Santo. DAS-28 amongst all plant-users was mild (Median DAS-28=2.2 (1.8-2.5)). Interestingly, M. albicans and Arnica users had the lowest scores among plant users (Median DAS-28= 2.0 (1.6-2.2) and 2.2 (1.0-2.6) respectively). Furthermore, DAS-28 was lower in users of M. albicans compared to users of other plant types (Median DAS-28= 2.0 (1.6-2.2) vs. 2.3 (1.9-2.7), t(47)= 0.3, p= 0.04).

Conclusion: Medicinal plant usage for viral arthritis is common in the Amazonas region. The findings highlight the widespread use of medicinal plants among participants, with a substantial proportion reporting improvements in pain, stiffness, and daily activities. Further exploration is needed into the role of traditional remedies in improving the quality of life for those affected by chikungunya arthritis, and to promote awareness and the development of potential treatments for chikungunya arthritis.

Keywords

Medicinal plants, Herbs, Chikungunya virus, Arthritis, Arthralgia, Stiffness, Pain, Inflammation

Introduction

Chikungunya virus (CHIKV) is an alphavirus spread by mosquitoes that is endemic to the Amazon region of Brazil [1]. One significant outbreak of CHIKV occurred between 2014 and 2018 In Roraima, Brazil, with 5,928 reported cases of chikungunya, of which 3,719 were confirmed in Boa Vista after phylogenetic analysis showed that the ECSA strain of the virus caused the outbreak in 2017 [2]. In a cross-sectional study of participants affected by this CHIKV outbreak in Roraima, the most common symptoms reported in the initial infection period were fever, joint pain, headache, myalgia, and eye pain [3].

Chikungunya infection is commonly associated with chronic rheumatism of the knees, hips, wrists, ankles, elbows, and metacarpophalangeal joints months to years after infection [4]. Interestingly, patients who developed chronic arthritis in the Roraima cohort reported experiencing a longer period of fever compared to those who did not develop arthritis. Chronic arthritis is characterized by moderate arthritis disease activity characterized by pain, stiffness and decreased quality of life [3]. There are limited evidence-based therapies for the treatment of post-chikungunya rheumatism. This study identified the use of certain popular species of medicinal plants for pain relief in approximately one-third of the cohort [3].

Historically, medicinal plants have been used in multiple scenarios. The therapeutic drug industry and pharmacological research highly value natural products and medicinal plant derivatives as therapeutic agents and sources for synthesizing active compounds. In addition, there is a popular demand for natural home remedies for the treatment of disease. This demand may stem from beliefs that natural remedies have fewer side effects and difficulty accessing medical care and pharmaceuticals that require a prescription [5]. Therefore, the objective of the current study was to further understand which medicinal plants are most used for post-chikungunya rheumatism in Amazonas, Brazil, and the attitudes, beliefs, and patterns of use of these medicinal plants. The long-term goal is to further awareness and development of potentially valuable therapies to treat post-chikungunya arthritis.

Methods

Ethics statement

The Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Roraima approved the study protocol under Opinion Number 5.980.722. All participants were adults who provided written informed consent during an in-person interview. Thorough precautions were taken to ensure that the data was kept confidential. The benefit for society includes a better understanding of disease treatment.

Study participants

Patients were recruited from primary care clinics in Roraima, Brazil, based on inclusion criteria which included being over the age of 18, experiencing arthralgia and reporting a history of CHIKV infection by epidemiologic nexus in the recent outbreaks of Chikungunya reported in the region. Participants were recruited through convenience sampling between May and September 2023. Most of the chikungunya cases were self-reported due to a lack of laboratory testing availability posing a limitation to this study.

Study design

A cross-sectional design was used [6] including an administered questionnaire from May to September of 2023.

Study site

Roraima is in Amazonas, Brazil and is endemic for chikungunya virus. Participants were recruited from the primary care clinics that are part of the Unified Health System of Roraima (SUS).

Data collection procedures

Upon diagnosis of chikungunya infection, a compulsory notification form is required by the public health system. Subjects with a history of reported chikungunya between 2014 to 2023 were contacted to inquire about their use of medicinal plants. After informed consent, the questionnaire was administered by our study coordinator and a joint exam was performed.

Assessments

The questionnaire collected information about the participants' use of medicinal plants, including the plant’s name, form of use (such as tea, capsules, ointments, or oils), dosage, frequency of use, duration of use, and the source of the plant. Participants were also asked whether they experienced improvements, specifically regarding stiffness, mobility, daily activities, and anxiety. Additionally, they were asked to share their perceptions of the risks and benefits associated with using the plants.

The examiner assessed the arthritis severity using the evaluation of joint swelling and tenderness of 28 joints included in the Disease Activity Score-28 (DAS-28). There was no blood draw as a part of this study and therefore a standardized CRP value of 1 was used to calculate the DAS-28 score to correlate arthritis activity with the participants' use of medicinal plants.

Statistical analysis

The data was tabulated in Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap), a secure online database. Analyses were conducted in GraphPad Prism 10™. Descriptive statistics are reported including frequency analyses of medicinal plant usage and patterns of use. Arthritis severity was described by the Disease Activity Score-28. A D'agostino & Pearson test was performed to test if arthritis severity data had a normal distribution. Arthritis severity was compared between medicinal plant users vs. non-users using a non-parametric unpaired t-test.

Results

Demographics

The study's population comprised 47 participants recruited from May to September 2023 in Roraima, Amazonas, Brazil. These individuals reported symptoms of arthralgia and had a documented history of chikungunya virus infection. The demographics of the study population are reported in Table 1. The mean age of the participants was 40.6 (± 15.6) years, with a predominance of females (59.6%). Two two-thirds of the study population completed at least secondary education. The ethnic composition of the group revealed a majority identifying as Mixed race (51.1%), followed by White (31.9%) and Black (17.0%). The mean monthly income was R$3978 which is equivalent to $640.40. The participants had been experiencing symptoms since their chikungunya infection for an average of 5.7 ±1.7 years.

|

Characteristic |

Participants with Chikungunya arthritis (N=47) |

|

Demographics |

|

|

Age (mean years, SD) |

40.6 (± 15.6) |

|

Female subjects (%) |

28/47 (59.6%) |

|

With at least secondary school education (%) |

31/47 (65.9%) |

|

Monthly income (mean Brazilian reais, SD) |

R$3,978 ± 1,707 ($640 ± 305 USD) |

|

Ethnicity n (%) |

Mixed 24 (51.1%) White 15 (31.9%) Black 8 (17.0%) |

|

Duration of time since CHIKV infection (mean years, SD) |

5.65 (±1.7)

|

|

Total swollen joint count (avg. number/ participant) |

31 (0.66 swollen joints/participant) |

|

Total tender joint count (mean per participant) |

156 (3.32 tender joints/participant) |

|

General health assessment (mean ± SD) |

47.6 (13.1) |

|

DAS-28 Median (IQR) calculated without CRP |

2.9 (2.2-3.4) among medicinal plants users |

Medicinal plant usage

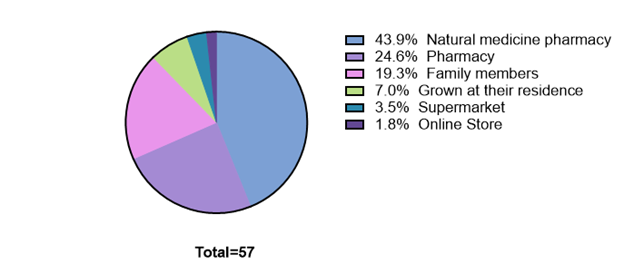

Among the participants, the majority (78.7%) reported using at least one type of medicinal plant, and 20 participants (42.6%) indicated using two different types. The most frequently used plants included Miconia albicans (36.8%), Arnica (26.3%), and a range of others such as Boswellia, Saffron, Ginger, Lemongrass, and Turmeric, each utilized by a smaller subset of participants (7.0% each) (Figure 1). Other less commonly used plants included Caimbé, Coconut, Lemon & Honey, Horse Chestnut, and Capim Santo, each used by 1.8% of the participants. Regarding the form of plant application (Figure 2), tea was the predominant method (52.6%). This was followed by ointments (28.1%), capsules, and oils (8.8% each), with juice being the least common form of administration (1.8%). This data highlights a prevalent inclination towards using a combination of medicinal plants, particularly in the form of tea, for managing post-viral arthralgia symptoms.

Figure 1. Usage of specific medicinal plants for chikungunya arthritis.

Figure 2. Where participants obtained the plants.

Arthritis disease severity

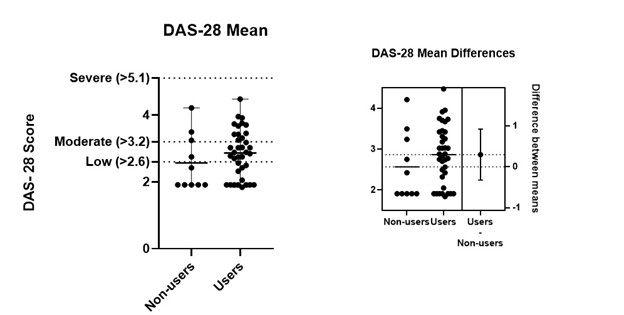

The DAS-28 score was initially designed to evaluate the severity of rheumatoid arthritis and has been used to measure chikungunya arthritis severity in previous studies [7-10]. The median DAS-28 score among participants was 2.2 (1.8-2.5), indicating low disease activity overall (Figure 3). An average of 3.4 tender joints per participant and 0.7 swollen joints per participant were reported. As no serum samples were collected, a C-reactive protein could not be included in the calculation of the DAS-28, and a normal CRP value of 1 was assumed for this calculation.

Figure 3. Mean disease activity (DAS-28 score) compared between those using medicinal plants vs. not using medicinal plants.

A mild disease activity score was reported among medicinal plant users and non-users (2.9 vs. 2.2, t(47)= 0.71, p= 0.24). Interestingly, the median arthritis disease activity among M. albicans and Arnica users was DAS-28= 2.0 (1.6-2.4) and 2.2 (1.0-2.6) respectively and were among the lowest within the medicinal plants user group. Additionally, the median arthritis disease activity was lower in M. albicans users versus users of other plant types (Median DAS-28= 2.0 (1.6-2.2) vs. 2.3 (1.9-2.7), t(47)= 0.3, p= 0.04).

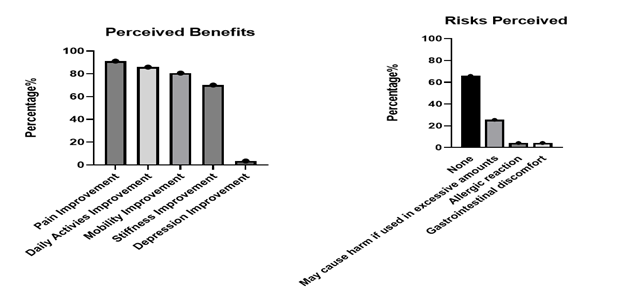

Perceived risks and benefits

The perceived risks and benefits of medical plant usage were assessed (Figure 4). Among those participants who were using medicinal plants, a significant proportion of them (78.7%) perceived a notable advantage in terms of cost compared to conventional treatments. Furthermore, participants identified the perceived lack of side effects (63.8%) as a significant benefit of medicinal plant usage, and a similar percentage (65.9%) reported no perceived risks associated with medicinal plant usage. Meanwhile, others reported risks of potential harm if used in excess (25.5%), risk of allergic reaction (4.3%), and risk of gastrointestinal discomfort (4.3%). Most participants (70.2%) did not observe greater efficacy in medicinal plant treatments compared to other pain management approaches. A majority (94.6%) of participants reported experiencing no discernible effects on depression or anxiety through their utilization of medicinal plants.

Figure 4. Perceived benefits vs. perceived risks.

Specific plant usage

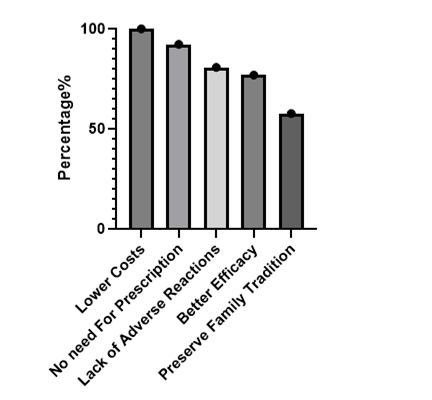

Regarding specific plant usage, Miconia albicans was the most utilized plant with 56.8% reporting its use. This prevalence was particularly notable among white females with a college education. Among M. albicans users the mean age was 41.9 ± 15.2 years and the mean income was R$4,029 ± R$2,005 which is equivalent to $767 ± $358 USD, which would classify them as upper-middle class in Brazil. The mean time since infection with chikungunya was 5.7 years. The most common perceived risk for M. albicans was that it “may cause harm if used in excessive amounts” reported in 55.6% of users (Table 2). As for the perceived benefits, 100% described a lower cost compared to conventional treatments, 94.4% preferred them due to a lack of need for a prescription and 57.1% reported better efficacy than pharmaceuticals as a benefit (Figure 6).

|

Clinical Characteristics Improved |

Medicinal Plant |

|

|

Miconia albicans |

Arnica |

|

|

Pain Improvement |

100% |

100% |

|

Mobility Improvement |

95.2% |

53.3% |

|

Stiffness Improvement |

90.5% |

40.0% |

|

Daily Activity Improvement |

95.2% |

66.7% |

|

Depression Improvement |

4.8% |

0% |

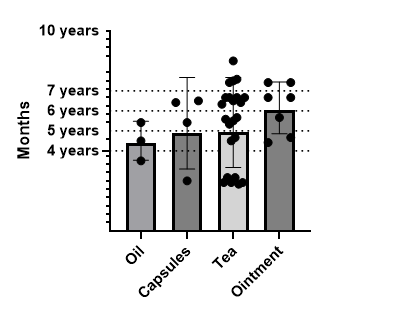

Figure 5. Time since CHIKV infection.

Figure 6. Reason for using medicinal plants.

The second most used plant was Arnica, with 18.9% using this medicinal plant. Arnica users were mostly mixed race (35.2%) women (57.1%) with a high school education (57.1%), and a mean income of R$3,620 ± R$1,535 which is equivalent to $689 ± $274 USD. The median arthritis disease activity among Arnica users was not significantly lower than non-users (DAS-28 = 2.2(1.0-2.6) vs. 2.0 (1.8-2.4), t(57)= 0.2, p= 0.62.) 71.4% of Arnica users did not perceive any risks associated with the plant. As for the perceived benefits, 100% described a lower cost and no need for prescription as important benefits but only 38.9% reported better efficacy as a benefit.

Furthermore, our analysis revealed a slight difference between the mode of administration and the duration since the chikungunya virus infection. Oils and capsules were predominantly used by individuals with shorter times since infection (54±12 and 63±22 months, respectively). In contrast, ointments were favored by those with a longer duration since infection, with a mean of 6.2 ± 1.3 years (74 ± 15 months) (Figure 5). This temporal association suggests a potential evolution in treatment preferences throughout Chikungunya's arthritis progression.

Discussion

The primary finding from this study was that medicinal plant usage was very common for post-viral arthritis. The most used medicinal plants included Miconia albicans and Arnica but included a wide range of other plants such as Boswellia, Saffron, Ginger, Lemongrass, Turmeric, Caimbé, Coconut, Lemon, Honey, Horse Chestnut, and Capim Santo. Medicinal plants have played a crucial role in treating different conditions in diverse cultures worldwide. Medicinal plants, deeply rooted in traditional medicine's spiritual and historical fabric, were once confined to specific communities [11]. However, their broader recognition as a valuable source of natural remedies that can enhance health, and well-being is a testament to the enduring wisdom of these cultural practices. The mechanisms involved that potentially explain the benefits of these plants in arthritis include the apoptosis effect, anti-inflammatory properties, anti-oxidative stress, and activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway [12]. Furthermore, compared to traditional treatments, their low cost has emerged as a popular and affordable option in specific low-income populations. The minimal side effects associated with these plants further bolster their appeal as natural alternatives [13].

We found that Miconia albicans was the most used medicinal plant in this chikungunya arthritis population. Research has shown that extracts of Miconia albicans possess anti-inflammatory properties, as evidenced by their anti-hyperalgesic and anti-inflammatory effects in a rodent arthritis model [14]. This anti-inflammatory activity is associated with modulation of key inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6. Additionally, phytochemical evaluation of Miconia albicans extracts has revealed their potential as anti-inflammatory agents, with compounds like quercetin and flavonoids contributing to these effects [15].

Furthermore, Arnica, a plant with a long history in traditional medicine, has been used for pain management in several North American and European countries. A. Montana is the most used type in over-the-counter herbal products. The efficacy of this plant in arthritis has been scientifically studied in different randomized clinical trials, these studies have consistently shown a reduction of pain in patients with hand, knee, and shoulder osteoarthritis secondary to the use of Arnica gel extract for a few weeks [16].

Boswellia Serratia contains boswellic acid and has been used in different chronic inflammatory diseases, including osteoarthritis [17]. This natural plant acts by inhibiting prostaglandin and NF-κB production providing its anti-inflammatory properties [18].

In a randomized clinical trial by Hameidi et al. (2020) [19], a 12-week treatment of saffron was used in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Results showed diminishing pain on the visual analog scale, swollen and tender joints, and DAS-28 levels thought to be due to the plant's anti-inflammatory properties.

Furthermore, ginger (Zingiber officinale) has demonstrated effectiveness as an alternative for pain management by inhibiting the cyclooxygenase enzymes (COX), leukotriene, and interleukin molecular signaling pathways contributing to a hypoalgesic effect [20]. In contrast, Turmeric has been shown to have pain reduction properties, however, does not operate via COX-1 inhibition, but modifies NF-κB and phospholipase A2 activity [21].

This study also reveals an interesting shift in the use of medicinal plants, showing that their use isn't limited to economically disadvantaged populations as often reported. Previous research has found that economic constraints lead lower-income groups to rely more on medicinal plants due to limited access to conventional healthcare [22]. These groups often developed a heightened perception of the plants' effectiveness because they became a primary healthcare resource. However, this study shows that even among middle-to-upper income participants, medicinal plants are commonly used. These individuals not only had knowledge about various plants and their uses but also grew their own plants and were aware of potential side effects. For them, medicinal plants were a practical and cost-effective option for managing their symptoms, even when conventional healthcare is accessible. This suggests that the appeal of medicinal plants extends beyond economic necessity, as they are valued for their perceived safety and efficacy across different income levels.

There were multiple limitations to this study. First, the diagnosis of chikungunya was not confirmed with confirmatory tests like PCR, which could affect the accuracy of the reported history of infection. Additionally, dengue fever, which is also prevalent in the region, was not ruled out as a potential confounding factor. Convenience sampling was employed potentially influencing bias. Blood samples were not available to test cytokine levels. Finally, the relatively small sample size limits the generalizability of the findings, and future research with a larger cohort of economically diverse participants followed with a longitudinal design is needed to understand better the broader implications of medicinal plant use in different populations.

Conclusion

In summary, our findings underscore the perceived benefits, efficacy, and demographic factors in shaping the utilization of medicinal plants among individuals grappling with chikungunya arthritis in Brazil. These benefits included lower costs, no need for a prescription, symptom improvement, and an absence of perceived adverse effects.

This study population consisted largely of individuals with above-average incomes and higher levels of education, with Miconia albicans as the most utilized plant. This diversity contrasts with the demographics observed in other studies consisting of mainly rural/low-income populations regarding the use of medicinal plants. Based on our findings, most participants reported significant benefits with little to no risk associated with medicinal plant usage. This finding opens the conversation for the use of medicinal plants as a safe and accessible complement to the current management of chikungunya arthritis. There is a need for further exploration into the role of traditional remedies in improving the quality of life for those affected by chikungunya arthritis.

While direct evidence on the use of Miconia albicans for viral arthritis treatment is scarce, its established anti-inflammatory properties and the involvement of key inflammatory cytokines suggest that it may hold promise as a natural remedy for alleviating inflammation associated with viral arthritis.

Conflicts of Interest

AYC reports consulting for Valneva and Bavarian Nordic. Other authors report no commercial interest or conflicts of interest in relation to this work.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the patients for their time dedicated to this study.

References

2. SESAU-CGVS. Secretaria de Estado da Saúde. Boletim Epidemiológico da Vigilância Entomológica [Internet]. Boa Vista (RR): Secretaria de Estado da Saúde; 2017 [cited 2019 Oct 25]. Available from: http://www.saude.rr.gov.br

3. Hayd RLN, Moreno MR, Naveca F, Amdur R, Suchowiecki K, Watson H, et al. Persistent chikungunya arthritis in Roraima, Brazil. Clin Rheumatol. 2020 Sep;39(9):2781-7.

4. Pathak H, Mohan MC, Ravindran V. Chikungunya arthritis. Clin Med (Lond). 2019 Sep;19(5):381-5.

5. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Boletim epidemiológico: monitoramento dos casos de arboviroses urbanas transmitidas pelo Aedes (dengue, chikungunya e Zika) até a semana epidemiológica 11 de 2019. Brasília (DF): Secretaria de Vigilância Epidemiológica; 2019.

6. Fontelles MJ, Simões MG, Farias SH, Fontelles RG. Metodologia da pesquisa científica: diretrizes para a elaboração de um protocolo de pesquisa. Rev. para. med. 2009;23:1-8.

7. Chang AY, Martins KAO, Encinales L, Reid SP, Acuña M, Encinales C, et al. Chikungunya Arthritis Mechanisms in the Americas: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of Chikungunya Arthritis Patients Twenty-Two Months After Infection Demonstrating No Detectable Viral Persistence in Synovial Fluid. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018 Apr;70(4):585-93.

8. Ganu MA, Ganu AS. Post-chikungunya chronic arthritis--our experience with DMARDs over two year follow up. J Assoc Physicians India. 2011 Feb;59:83-6.

9. Pandya S. Methotrexate and hydroxychloroquine combination therapy in chronic chikungunya arthritis: a 16 week study. Indian Journal of Rheumatology. 2008 Sep 1;3(3):93-7.

10. Tritsch SR, Encinales L, Pacheco N, Cadena A, Cure C, McMahon E, et al. Chronic Joint Pain 3 Years after Chikungunya Virus Infection Largely Characterized by Relapsing-remitting Symptoms. J Rheumatol. 2020 Aug 1;47(8):1267-1274. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.190162. Epub 2019 Jul 1. Erratum in: J Rheumatol. 2021 Aug;48(8):1350.

11. Srivastava AK. Significance of medicinal plants in human life. InSynthesis of Medicinal Agents from Plants 2018 Jan 1 (pp. 1-24). Elsevier.

12. Wang Z, Efferth T, Hua X, Zhang XA. Medicinal plants and their secondary metabolites in alleviating knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review. Phytomedicine. 2022 Oct;105:154347.

13. Kitula RA. Use of medicinal plants for human health in Udzungwa Mountains Forests: a case study of New Dabaga Ulongambi Forest Reserve, Tanzania. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2007 Jan 26;3:7.

14. Quintans-Júnior LJ, Gandhi SR, Passos FRS, Heimfarth L, Pereira EWM, Monteiro BS, et al. Dereplication and quantification of the ethanol extract of Miconia albicans (Melastomaceae) by HPLC-DAD-ESI-/MS/MS, and assessment of its anti-hyperalgesic and anti-inflammatory profiles in a mice arthritis-like model: Evidence for involvement of TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6. J Ethnopharmacol. 2020 Aug 10;258:112938.

15. Manzano MI, Centa A, Veiga AA, da Costa NS, Bonatto SJR, de Souza LM, et al. Phytochemical Evaluation and Anti-Inflammatory Potential of Miconia albicans (Sw.) Triana Extracts. Molecules. 2022 Sep 13;27(18):5954.

16. Smith AG, Miles VN, Holmes DT, Chen X, Lei W. Clinical Trials, Potential Mechanisms, and Adverse Effects of Arnica as an Adjunct Medication for Pain Management. Medicines (Basel). 2021 Oct 9;8(10):58.

17. Kaur C, Mishra Y, Kumar R, Singh G, Singh S, Mishra V, Tambuwala MM. Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and herbal medicine-based therapeutic implication of rheumatoid arthritis: an overview. Inflammopharmacology. 2024 Jun;32(3):1705-20.

18. Verhoff M, Seitz S, Paul M, Noha SM, Jauch J, Schuster D, et al. Tetra- and pentacyclic triterpene acids from the ancient anti-inflammatory remedy frankincense as inhibitors of microsomal prostaglandin E(2) synthase-1. J Nat Prod. 2014 Jun 27;77(6):1445-51.

19. Hamidi Z, Aryaeian N, Abolghasemi J, Shirani F, Hadidi M, Fallah S, et al. The effect of saffron supplement on clinical outcomes and metabolic profiles in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Phytother Res. 2020 Jul;34(7):1650-8.

20. Black CD, Herring MP, Hurley DJ, O'Connor PJ. Ginger (Zingiber officinale) reduces muscle pain caused by eccentric exercise. J Pain. 2010 Sep;11(9):894-903.

21. Daily JW, Yang M, Park S. Efficacy of Turmeric Extracts and Curcumin for Alleviating the Symptoms of Joint Arthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. J Med Food. 2016 Aug;19(8):717-29.

22. Corroto F, Rascón J, Barboza E, Macía MJ. Medicinal Plants for Rich People vs. Medicinal Plants for Poor People: A Case Study from the Peruvian Andes. Plants (Basel). 2021 Aug 9;10(8):1634.