Abstract

COVID-19 has been identified as a virus spread to the respiratory system by minute airborne particles. This method of dispersion is in contrast to its originally anticipated large particle fomite transmission. Although COVID-19 dissemination has been found to be airborne, a continuous health directive to limit contagion during the pandemic was to improve handwashing. Persistent handwashing may aggravate obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), diminishing mental health. With a modest value to handwashing in controlling the spread of COVID-19, determining if the handwashing directive increased the incidence of OCD, promoting negative mental health, is pertinent. A limited review of the parameter “handwashing, mental health, COVID-19, OCD” searched six relevant databases. The result was that negative mental health related to increased handwashing was evident both for those already diagnosed with OCD and regarding new cases of OCD throughout the duration of the pandemic. The exception was for those very few OCD patients demonstrating resilience or on stable medication. The conclusion is that health officials are advised to update details of their health directives as information becomes available during a pandemic. Concerning COVID-19, the directive to concentrate on handwashing should have been modified once it was known that spread of the virus by fomite transmission was improbable, as doing so would have reduced the incidence of OCD and improved mental health of those experiencing OCD. Regarding improved mental health, further OCD research is indicated regarding both resilience and stable medication under pandemic conditions when increased hand-washing is advised.

Keywords

COVID-19, Fomite transmission, Health directive, Handwashing, Obsessive-compulsive disorder, OCD, Mental health

Introduction

Stating what was then known of the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in relation to the 2020-2023 COVID-19 pandemic, an article published in Nature on 29 January 2021 [1] indicated that transmission was through airborne aerosolized droplets directly inhaled by contacts [2]. This was in contrast to earlier modeling and epidemiological observations that had implicated the spread of the virus through large respiratory droplets settled on surfaces and transferred to contacts' mucosal membranes (fomite transmission) [3]. Although there is evidence that the COVID-19 virus persists on certain surfaces for up to 72 hours [4], according to the Nature article, this viral RNA “is the equivalent of the corpse of the virus—It’s not infectious.” Furthermore, the article also stressed, “Fomite transmission is possible, but it just seems to be rare” [1].

The initial predictions regarding how the COVID-19 virus was spread were based on expectations comparing its transmission to that of other common respiratory viruses [3]. However, each virus type has a different interaction mechanism with fomites, and this is affected by several variables [5]. Continuing research reinforced the rarity of fomite transmission regarding COVID-19 [6-9], recognizing that fomite transmission was still possible in the spread of the COVID-19 virus [1].

Yet, the problem remained that cleansing surfaces and hands to control COVID-19 was stressed in a manner equivalent to improving ventilation [10]—although, in reducing aerosolized droplets, enhancing ventilation was the superior method to cleansing in controlling the spread of the virus [11]. Nevertheless, the call from the World Health Organization (WHO) for frequent and better handwashing along with other cleansing was maintained as an excellent method to reduce the incidence of COVID-19 [12].

Handwashing has been demonstrated to be potent in killing viruses if properly completed [13]. For this reason, handwashing is an easy precaution to take and might be effective [14]. What has not been taken into consideration by authorities who have continued their support of persistent handwashing among the measures to reduce the spread of the virus is those who obsess regarding handwashing, diagnosed with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD), and those who became newly diagnosed as a result of this health directive—producing negative mental health in those affected [15].

OCD is defined by the American Psychiatric Association as patterns of unwanted and intrusive thoughts, images, or urges and repetitive behaviors that are intended to decrease the resulting distress from the compulsions [16]. OCD symptoms often include a fear of contamination which then triggers ritualized handwashing and other cleaning behaviors to neutralize the thought [14]. The widespread public health demands for increased and “proper” handwashing, cleaning, and use of disinfectants as a result COVID-19 may have been especially problematic for these patients with OCD, putting them at risk for developing excessive pandemic-related fears [17] leading to negative mental health.

This is the first paper to consider the role of handwashing alone in a limited review of both those previously diagnosed with OCD and those who developed OCD during COVID-19, with respect to the negative mental health they experienced as a result of the health directive to increase handwashing to protect against the transmission of the COVID-19 virus. As such, this paper aims to examine the extent of those with OCD whose mental health was negatively affected as a result of the directive to increase the amount they wash their hands during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The main conclusions are that the majority of those previously diagnosed with OCD before the pandemic—and all of those diagnosed during COVID-19—experienced negative mental health. Therefore, it is advised that information by health officials regarding the transmission of COVID-19 and future pandemic-related viruses be reconsidered as additional information becomes available regarding transmission. Furthermore, also suggested is that this updated information include sufficient details concerning the type of handwashing required. In doing so, those susceptible to OCD are informed that it is unnecessary for them to increase their already thorough and persistent handwashing behavior in protecting themselves from COVID-19 and future pandemic virus transmission. The effect of doing so is anticipated to aid in maintaining their mental health. As OCD patients who demonstrated resilience—as well as a seemingly small percentage of those on stable medication—did not experience negative mental health, additional conclusions are that research investigate both (1) ways to teach resilience to those diagnosed with OCD to protect their mental health, and (2) the types of stable medication with the potential to support mental health regarding OCD during COVID-19, and future pandemics.

Materials and Methods

Study design

This examination is a limited review of a parameter with the following keywords, “handwashing, mental health, COVID-19, OCD.” The databases searched include OVID, PubMed, ProQuest, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar.

Searched records returned

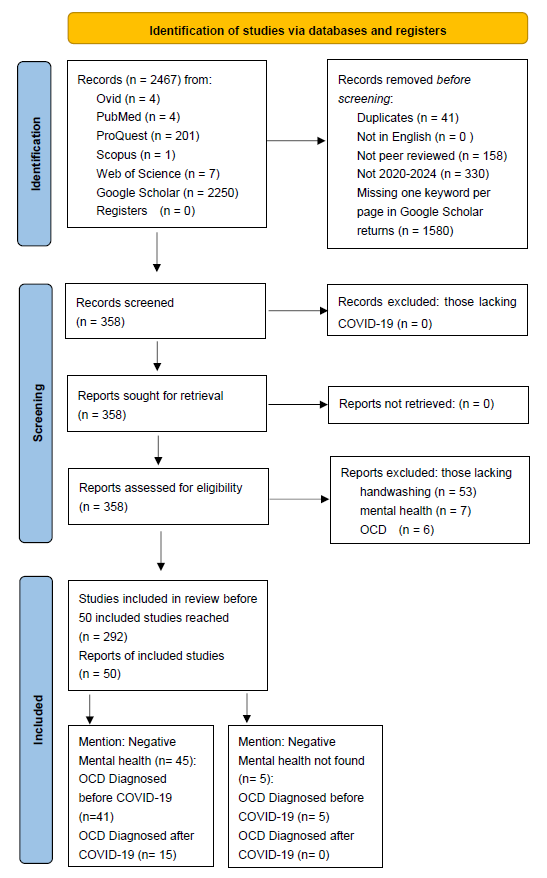

In total, 2,467 individual records were returned from six different database searches of the keywords “handwashing, mental health, COVID-19, OCD.” The databases searched and the number of records returned were as follows: OVID (n = 4), PubMed (n = 4), ProQuest (n = 201), Scopus (n = 1), Web of Science (n = 7), and Google Scholar (n = 2250). There were no registers searched. Of these records, those removed included duplicates (n = 41), not in English (n = 0), not peer reviewed (n = 158), not published between 2020-2024 (n = 330), and missing one keyword per page in the Google Scholar search returns (n = 1580). Of the remainder, there were 358 records to be screened with none excluded for lacking COVID-19. Consequently, all 358 reports were sought for retrieval, and all were retrieved. The result was 358 reports to be assessed for eligibility. Excluded were those lacking: handwashing (n = 53), mental health (n = 7), and OCD (n = 6). Thus, 292 studies were included (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flowchart for a limited review regarding a search of the parameter with the keywords, “handwashing, mental health, COVID-19, OCD” in the following databases: Ovid, PubMed, ProQuest, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar No registers were searched.

Studies included

A total of 50 articles were investigated from all databases searched with 20 articles provided by the primary database searches, and 30 articles included from the Google Scholar search. The total number of reports included from each of the six databases is represented in Table 1.

|

Database |

Citation |

Truncated Titles of Studies Included |

|

OVID |

Demaria et al., 2022 [50] |

Hand Washing: When Ritual Behavior Protects! |

|

OVID |

Dennis et al., 2021 [18] |

A Perfect Storm? |

|

OVID |

Alateeq et al., 2021 [29] |

The Impact of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic |

|

OVID |

Abba-Aji et al., 2020 [19] |

COVID-19 Pandemic and Mental Health |

|

PubMed |

Hezel et al., 2022 [33] |

Resilience Predicts Positive Mental Health Outcomes |

|

PubMed |

Ornell et al., 2021 [51] |

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Reinforcement |

|

PubMed |

de Jesus et al., 2023 [52] |

Conradi-Hünerman-Happle Syndrome |

|

ProQuest |

Gokhale & Chakole, 2022 [38] |

A Review of Effects of the Pandemic |

|

ProQuest |

Perkes et al., 2020 [34] |

Contamination Compulsions |

|

ProQuest |

Fiaschè et al., 2023 [20] |

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder |

|

ProQuest |

Taher et al., 2021 [21] |

Prevalence of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder |

|

ProQuest |

Bibawy et al., 2023 [30] |

A Case of New-Onset Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder |

|

ProQuest |

Hassan et al., 2021 [22] |

The Impact of COVID-19 Social Distancing |

|

ProQuest |

Chakraborty & Karmakar, 2020 [35] |

Impact of COVID-19 |

|

ProQuest |

Mushtaq et al. 2022 [53] |

The Well-Being of Healthcare Workers |

|

ProQuest |

D’Urso et al., 2023 [54] |

Effects of Strict COVID-19 Lockdown |

|

ProQuest |

Costa et al., 2021 [31] |

A Case of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder |

|

Web of Science |

Malas & Tolsa, 2022 [23] |

The COVID-19 Pandemic |

|

Web of Science |

Sulaimani & Bagadood, 2021 [55] |

Implications of Coronavirus Pandemic |

|

Web of Science |

Kumar & Somani, 2020 [56] |

Dealing with Corona Virus Anxiety |

|

Google Scholar |

Shafran & Coughtrey, 2020 [57] |

Recognising and Addressing the Impact of COVID-19 |

|

Google Scholar |

Van Ameringen et al, 2022 [17] |

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder During the COVID-19 |

|

Google Scholar |

Kumar & Nayar, 2021 [58] |

COVID-19 and its Mental Health Consequences |

|

Google Scholar |

Hassoulas et al, 2022 [59] |

Investigating the Association |

|

Google Scholar |

Matsunaga et al, 2020 [60] |

Acute impact of COVID-19 Pandemic |

|

Google Scholar |

Linde et al., 2022 [61] |

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder During the COVID-19 Pan. |

|

Google Scholar |

Jassi et al., 2020 [24] |

OCD and COVID-19: a New Frontier |

|

Google Scholar |

Quittkat et al., 2020 [62] |

Perceived Impact of COVID-19 |

|

Google Scholar |

French & Lyne, 2020 [63] |

Acute Exacerbation of OCD Symptoms |

|

Google Scholar |

Sahoo et al., 2020 [64] |

COVID-19 as a “Nightmare” |

|

Google Scholar |

Maye et al., 2022 [65] |

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder During the COVID-19 Pand. |

|

Google Scholar |

Berman et al., 2022 [66] |

COVID-19 and Obsessive-Compulsive Symptoms |

|

Google Scholar |

Davide et al., 2020 [67] |

The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic |

|

Google Scholar |

Jain et al, 2020 [25] |

COVID-19 and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder |

|

Google Scholar |

El Othman et al., 2021 [26] |

COVID-19 Pandemic and Mental Health in Lebanon |

|

Google Scholar |

Cunning & Hodes, 2022 [68] |

The COVID-19 Pandemic and Obsessive–Compulsive Dis. |

|

Google Scholar |

Dar et al., 2021 [32] |

Psychiatric Comorbidities Among COVID-19 Survivors |

|

Google Scholar |

Jalal et al., 2022 [69] |

Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder—Contamination Fears |

|

Google Scholar |

Sowmya et al., 2021 [70] |

Impact of COVID-19 on Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder |

|

Google Scholar |

Wheaton et al., 2021 [49] |

How is the COVID-19 Pandemic Affecting Individuals |

|

Google Scholar |

Brewer et al., 2022 [36] |

Experiences of Mental Distress during COVID-19 |

|

Google Scholar |

Samuels et al., 2021 [27] |

Contamination-Related Behaviors, Obsessions |

|

Google Scholar |

Jelinek et al., 2021 [71] |

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder During COVID-19 |

|

Google Scholar |

Darvishi et al., 2020 [28] |

A Cross-Sectional Study on Cognitive Errors |

|

Google Scholar |

Sharma et al., 2021 [37] |

Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic |

|

Google Scholar |

Grant et al., 2022 [72] |

Obsessive-Compulsive Symptoms and the Covid-19 Pandem. |

|

Google Scholar |

Siddiqui et al, 2022 [73] |

The Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Individuals |

|

Google Scholar |

Sadri Damirchi et al, 2020 [74] |

The Role of Self-Talk in Predicting Death Anxiety |

|

Google Scholar |

Silva Moreira et al., 2021 [75] |

Protective Elements of Mental Health Status |

|

Google Scholar |

Zaccari et al., 2021 [76] |

Narrative Review of COVID-19 Impact |

Results

Of the 50 articles included from all databases searched, 45 mentioned negative mental health. Of the 46 reports that concerned those diagnosed with OCD before the pandemic, 41 of them found negative mental health in those diagnosed. Of the 15 reports investigating OCD in those who developed symptoms during COVID-19, all 15 reported negative mental health in these individuals. In contrast, negative mental health was not found in only 5 of the 50 reports included. Of these, all 5 were identified with those who were diagnosed with OCD before COVID-19—0 for those diagnosed during the pandemic.

With the results of the 50 included reports, a table can be constructed indicating the articles that concern those diagnosed with OCD before COVID-19, those diagnosed during COVID-19, and whether, for either of these, their negative mental health was indicated. Table 2 represents this compilation. What is evident from the table is that although most articles (39 or 78%) focused on either those diagnosed with OCD before or after, there were 11 (22%) that concerned both [18-28]. Interesting to recognize is, of these 11 articles—where their authors looked at both those previously diagnosed with OCD and those whose OCD symptoms were newly identified during COVID-19—each of them considered that the directive by health authorities to increase handwashing had a detrimental effect on the mental health of those studied, producing negative mental health. Furthermore, of the studies that concerned only those with new symptoms of OCD during COVID-19 brought on by increased handwashing, all also found negative mental health [29-32] (4 or 8%). Therefore, the only articles that did not detect negative mental health were some that investigated those diagnosed with OCD before the pandemic. There were 34 articles that discussed only those previously diagnosed with OCD. Of these, 5 or 14.7% of them [33-37] stated that there was no negative mental health in those diagnosed with OCD, equaling 10% of the total articles.

|

Truncated Titles of Studies Included |

OCD Diagnosis Before |

OCD Diagnosis During |

Negative Mental Health |

|

Hand Washing: When Ritual Behavior Protects! |

✓ |

✘ |

✓ |

|

A Perfect Storm? |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

The Impact of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic |

✘ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

COVID-19 Pandemic and Mental Health |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Resilience Predicts Positive Mental Health Outcomes |

✓ |

✘ |

✘ |

|

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Reinforcement |

✓ |

✘ |

✓ |

|

Conradi-Hünerman-Happle Syndrome |

✓ |

✘ |

✓ |

|

A Review of Effects of Pandemic |

✓ |

✘ |

✓ |

|

Contamination Compulsions |

✓ |

✘ |

✘ |

|

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Prevalence of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

A Case of New-Onset Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder |

✘ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

The Impact of COVID-19 Social Distancing |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Impact of COVID-19 (India) |

✓ |

✘ |

✘ |

|

The Well-Being of Healthcare Workers |

✓ |

✘ |

✓ |

|

Effects of Strict COVID-19 Lockdown |

✓ |

✘ |

✓ |

|

A Case of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder |

✘ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

The COVID-19 Pandemic |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Implications of Coronavirus Pandemic |

✓ |

✘ |

✓ |

|

Dealing with Corona Virus Anxiety |

✓ |

✘ |

✓ |

|

Recognising and Addressing the Impact of COVID-19 |

✓ |

✘ |

✓ |

|

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder During the COVID-19 |

✓ |

✘ |

✓ |

|

COVID-19 and its Mental Health Consequences |

✓ |

✘ |

✓ |

|

Investigating the Association |

✓ |

✘ |

✓ |

|

Acute impact of COVID-19 Pandemic |

✓ |

✘ |

✓ |

|

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder During the COVID-19 Pan. |

✓ |

✘ |

✓ |

|

OCD and COVID-19: a New Frontier |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Perceived Impact of COVID-19 |

✓ |

✘ |

✓ |

|

Acute Exacerbation of OCD Symptoms |

✓ |

✘ |

✓ |

|

COVID-19 as a “Nightmare” |

✓ |

✘ |

✓ |

|

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder During the COVID-19 Pand. |

✓ |

✘ |

✓ |

|

COVID-19 and Obsessive-Compulsive Symptoms |

✓ |

✘ |

✓ |

|

The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic |

✓ |

✘ |

✓ |

|

COVID-19 and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

COVID-19 Pandemic and Mental Health in Lebanon |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

The COVID-19 Pandemic and Obsessive–Compulsive Dis. |

✓ |

✘ |

✓ |

|

Psychiatric Comorbidities Among COVID-19 Survivors |

✘ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder—Contamination Fears |

✓ |

✘ |

✓ |

|

Impact of COVID-19 on Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder |

✓ |

✘ |

✓ |

|

How is the COVID-19 Pandemic Affecting Individuals |

✓ |

✘ |

✓ |

|

Experiences of Mental Distress during COVID-19 |

✓ |

✘ |

✘ |

|

Contamination-Related Behaviors, Obsessions |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder During COVID-19 |

✓ |

✘ |

✓ |

|

A Cross-Sectional Study on Cognitive Errors |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic |

✓ |

✘ |

✘ |

|

Obsessive-Compulsive Symptoms and the Covid-19 Pandem. |

✓ |

✘ |

✓ |

|

The Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Individuals |

✓ |

✘ |

✓ |

|

The Role of Self-Talk in Predicting Death Anxiety |

✓ |

✘ |

✓ |

|

Protective Elements of Mental Health Status |

✓ |

✘ |

✓ |

|

Narrative Review of COVID-19 Impact |

✓ |

✘ |

✓ |

The vast majority of the included reports found negative mental health in those previously diagnosed with OCD. If the report investigated only those who developed symptoms during COVID-19—or both groups—then the view was unanimous that the health directive to increase handwashing during COVID-19 exacerbated negative mental health. Consequently, it is pertinent to discuss in detail those five articles that found there to be no negative mental health in those already displaying OCD symptoms before COVID-19, concerning the directive to increase handwashing. The articles to be discussed include: “Resilience Predicts Positive Mental Health Outcomes” [33], “Contamination Compulsions” [34], “Impact of COVID-19” [35], “Experiences of Mental Distress during COVID-19” [36], and “Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic” [37]. The purpose of this discussion will be to determine why the authors of these papers judged that there was no negative mental health and if this judgment can be considered to be based on the evidence presented in the studies performed for these reports.

Five articles not finding negative mental health in those diagnosed with OCD

Presented here will be the five articles that did not find negative mental health in those who had been diagnosed with OCD pre-COVID-19 of the articles included in this review.

Article 1. “Resilience Predicts Positive Mental Health Outcomes” [33] is the first of the five articles of those already diagnosed with OCD before the pandemic that did not find negative mental health in response to the health directive to increase handwashing. The reason for this finding among these New York City psychiatric patients is that some patients demonstrated resilience with respect to their OCD symptoms. For those who were resilient, these authors found that there was no resulting negative mental health. That said, the authors also point out that, “less resilience was associated with worsening obsessive-compulsive symptoms.” In effect, it was not that this study did not find negative mental health in those already diagnosed with OCD during COVID-19. It was only for those with OCD who were resilient that there was no negative mental health. Why these authors concentrated on the resilience demonstrated by only some of those with OCD seems to be that their original hypothesis was that all those with OCD would suffer from negative mental health. They were then surprised to find that not all those with OCD had negative mental health in response to the handwashing directive.

The authors speculated that the reasons for some expressing high resilience could be (1) those affected used the pandemic as motivation to confront their OCD symptoms, (2) lockdowns may have permitted those with OCD to avoid situations that would otherwise exacerbate their symptoms, and (3) those with higher resilience were better able to manage their symptoms and persist with treatment regardless of the pandemic. The quantitative data that were gathered seemed to support both the first two possibilities. Yet, there were few of those with OCD studied for this report who fit into this category of resilience. As such, the conclusion of the authors that negative mental health was not found oversteps the information provided throughout the majority of the article. Most likely the authors directed their attention to those demonstrating resilience because, as they note, resilience can be taught. However, that resilience can be taught does not mean it can be taught to those with negative mental health who have OCD symptoms related to handwashing. Although the resilience of some patients is a hopeful finding, further research is needed in this area to determine if resilience can be taught to OCD patients with negative mental health.

Article 2. The second article that found no negative mental health in those with OCD confronting the directive to increase handwashing during COVID-19 is one regarding patients seen by Australian psychiatrists. The article is “Contamination Compulsions” [34]. Although this one-page letter to the editor admits that some patients with OCD had increased anxiety during the pandemic, others with OCD reported feeling reassured and validated by the strict guidelines about handwashing. The authors conclude, “Our early anecdotal evidence appears to suggest that COVID-19 has had an unexpected positive impact on the mental health of some, but not all, people with OCD.” Although these authors admit that there is no universal finding regarding the mental health of those with OCD with respect to handwashing during the pandemic, with no controlled-study evidence to present, these authors have made it appear in their conclusion that a positive impact of the handwashing directive for COVID-19 is to be expected in patients with OCD. This conclusion goes beyond the evidence presented.

Article 3. “Impact of COVID-19” [35] is a paper regarding those with OCD in West Bengal based on phone interviews with psychiatric patients who had each been prescribed drug treatment for their OCD symptoms. During the time the survey was undertaken to determine if their symptoms had been exacerbated by the handwashing directive, 57 were continuing to take their medication during the pandemic, 13 took them irregularly due to fear of possible unavailability, and 14 had stopped taking their medicines due to unavailability at nearby drug stores. Of this group, only 5 (6%) of the patients reported any negative change in their mental health as a result of the pandemic directive to increase handwashing and, of those 5 patients, all of them were those who had stopped taking their medication. Consequently, it might be concluded what is necessary to keep mental health from being negative in this regard is to have the patients on the right medication and ensure that they are continuing to take them.

However, although all of the 5 patients who experienced negative mental health were those who had stopped taking their medication, this left 9 of those who had stopped taking their medication who claimed they did not experience negative mental health. If being on medication was the reason for not experiencing negative mental health, these 9 patients who stopped their medication should have reported negative mental health as well. Furthermore, the educational background of the patients is unclear, but it can be assumed to be low if the educational background is reported as the reason the authors chose a phone interview rather than an online survey. As such, if these patients lacked the education to access the internet, they may have felt that if an official contacts them to ask questions about the medication they are receiving for their OCD—and they are afraid that they may lose their prescription if they don’t answer the survey to say they feel fine with their medication—it can be supposed this fear may have been a reason why only those who weren’t taking their medication because it wasn't available felt safe in saying that their symptoms had got worse, indicating negative mental health. Given that these results are an anomaly in the research conducted on those with OCD in response to the health directive to increase handwashing during COVID-19, the lack of negative mental health in these patients is unexpected and requires further details that are unavailable to confirm the result.

Article 4. The fourth article, “Experiences of Mental Distress during COVID-19” [36], investigated the experiences of those with OCD seeking peer support in discussion forums of a popular social networking discussion forum platform (Reddit) during the COVID-19 pandemic. What is unique about this study as compared to others is its focus on discussions those with OCD had with others diagnosed with the same disorder. Their comments recorded for the study include statements such as, “Being advised to do all the things that I did anyway almost gives me a sense of normality. I haven’t felt normal in years,” and “It’s funny how the same people that made fun of me for not touching doorknobs, only eating off paper or plastic plates and silverware, and washing my hands till they bleed are becoming more and more ‘like me’.” To this extent, this study did not find negative mental health in these Reddit forum users.

However, others provided comments to the forum that were less self-assured, demonstrating negative mental health, “Being more conscious about germs and washing hands more regularly isn't necessarily a bad thing at the moment. Arguably we are positioned better than most of the population in terms of protecting ourselves because we already are thinking so much about germs and contamination. But I'm at that point where my increased caution is no longer useful and has begun to hinder my daily functioning again,” or “The last week COVID has made me worse again. I feel I need to wash my hands or sanitize everything after I touch things, and I'm only in my house. It's driving me crazy, I'm obviously wiping surfaces, taps, door handles etc. down regularly but I still feel as if I need to wash and feel clean otherwise I can't relax.”

Although Reddit permitted users with OCD the opportunity to express a new feeling of normalcy, this was insufficient for the authors to ignore the increase in negative mental health of those Reddit users brought on by the handwashing directive of the pandemic.

Article 5. The final article that did not find negative mental health in those diagnosed with OCD before the pandemic as a result of the health directive to increase handwashing is “Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic” [37]. This is a report of a study of 240 psychiatric patients who attended an OCD clinic at a hospital in India and were later followed up with two telephone interviews several months apart. All patients were on OCD medication. Similar to the other telephone study of OCD psychiatric patients in India, only 6% of patients reported negative mental health. This was an unexpected result by the investigators, given previous studies in the literature reporting negative mental health. Also similar to the other Indian study, most of the patients were on stable doses of medications, implying that continued treatment with medication may have prevented negative mental health. However, unlike the other study in India, this study did not collect information on the education level of the participants. Furthermore, the information was again collected by telephone and the questions asked are not included in the methods section of the report. It can again be queried if the patients did not mention negative changes in their mental health to those conducting the survey for fear that the purpose of the survey was to find a reason to stop medication. As such, there is insufficient information provided on the demographics of the patients and the questions asked of them to determine why the investigators recognized so few instances of negative mental health.

Discussion

Each of the five articles that did not find negative mental health in OCD patients who had been diagnosed previous to COVID-19 therefore has made this assessment for questionable reasons. The first paper [33] actually did find negative mental health in OCD patients; however, the concentration of the article was on those patients who were resilient, and it was those who did not have negative mental health. The second article [34] by Australian psychiatrists is a one-page letter based on anecdotal evidence alone. As such, the results are not scientifically sound. The third report [35] and the fifth [37] were both conducted in India under similar circumstances that may have put indirect pressure on the respondents to say that they did not experience negative mental health in case they might lose their right to medication as a result. The fourth report [36], similar to the first, actually did find negative mental health in some of the Reddit users, the paper’s authors chose to focus on those who did not experience negative mental health. As a final appraisal, it remains unclear whether these five papers that differed in their assessment of the effect of the handwashing directive on OCD patients diagnosed before the pandemic actually did have results that differed substantially from the other reports included that found negative mental health.

Implications

What can be identified from three of these papers [33,34,36] is that resilience matters to the mental health experience of those with OCD in relation to the handwashing directive. Resilience was displayed by some New Yorkers with OCD, most OCD patients of Australian psychiatrists, and some of those who used Reddit to communicate with others diagnosed with OCD. That resilience may be effective in reducing symptoms of OCD during COVID-19 has been recognized in other studies [39,40]. Furthermore, it is those with low resilience who are most likely to have demonstrated negative mental health [23]. In that resilience can be taught [41], this provides a potential way in which those diagnosed with OCD who experienced negative mental health as a result of the directive to increase handwashing might be able to overcome their symptoms to some degree with improved resilience. Such resilience generally has been recognized as necessary for all those demonstrating negative mental health as a result of the pandemic [42]. However, whether OCD patients who were negatively affected by the directive to increase their handwashing during COVID-19 are the type of patients who can be expected to gain from being taught resilience is uncertain. One method that seems to have been effective in this regard is reported in relation to a study of 8 OCD patients conducted early in the pandemic [43]. However, as it has been noted that OCD is linked with anger experience and expression from an incohesive and unempathetic family life [44,45], these more fundamental problems likely require attention for the teaching of resilience to be effective in OCD patients.

In considering the two reports from India [35,37] demonstrating little negative mental health in OCD patients who were on stable medication, it needs to be considered if maintaining stable medication during COVID-19 was sufficient to protect against negative mental health concerning the directive to increase handwashing during the pandemic for this group. Yet, apart from these two Indian articles, there appears to be no additional research to support the claim that stable medication is enough in this regard. Other research studies considering the adequacy of stable OCD medication regarding protecting against negative mental health during the pandemic found instead that negative mental health developed to the extent that previously stable medication had to be adjusted to affect regaining mental health in these patients [46,47]. In one survey group, 73% of OCD patients on stable selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor medication saw a worsening of their symptoms during COVID-19 [48]. Nevertheless, in a study that reported most OCD patients on stable medication experienced negative mental health [49], one survey respondent provided this positive comment, “I am very fortunate that my medication has been keeping my OCD under very good control,” demonstrating that, although rare, stable medication was able to maintain the mental health in at least some OCD patients, concurring with the findings of the two Indian articles.

Conclusion

The following represents the significance of this limited review conducted of the parameter containing the keywords “handwashing, mental health, COVID-19, OCD.”

Limitations

A limitation of this study is that the author did not provide a detailed account of the 45 reports that found negative mental health in those who had both been diagnosed with OCD before COVID-19 and those diagnosed during the pandemic. Given that the point of this examination is to present a limited review regarding “handwashing, mental health, COVID-19, OCD”—researchers who would like to check the accuracy of the author’s assessment have been provided with the type of transparency to make such an examination possible [50-76].

To this point, an additional limitation is that the evaluation of the articles for their authors’ points of view regarding negative mental health and OCD was contingent on the reading done by this author. Although this author undertook the present study with the aim of objectivity, it is possible that the author had a cognitive bias that was unrecognized [77]. Although various frameworks have been developed to debias research, there remains little research on the efficacy of these models and, as such, how to recognize and reduce cognitive bias is identified as an area in need of additional research [77].

Main outcomes

This limited review has demonstrated that the great majority of those diagnosed with OCD both before COVID-19, and those diagnosed after, sustained negative mental health based on the directive regarding handwashing during COVID-19. However, it was also noted that it was those with the least resilience who experienced the greatest negative mental health, and negative mental health was not a factor for those OCD patients who demonstrated resilience. Nevertheless, resilience generally is not present in those experiencing OCD, especially during the pandemic. Furthermore, it was found that stable medication might be a protective factor for those who were diagnosed with OCD pre-pandemic, although this finding is generally not supported.

Given these results, for this particular pandemic that was not fueled by fomite transmission, health officials might have supported the mental health of those with OCD if they had reconsidered and been more specific regarding their directive regarding handwashing when the information became available that airborne aerosol droplets were the cause of transmission.

Future perspectives

For future pandemics, an early effort should be made to determine the method of transmission of these viruses so that health directives can match what is likely to protect populations, including the most vulnerable to particular directives, thus reducing the possibility that negative mental health will result in those with OCD if increased handwashing is the directive. Moreover, given the importance of resilience in maintaining mental health, research should continue regarding how resilience might be increased in those with OCD symptoms experiencing negative mental health so that they might be able to mitigate their negative mental health under future pandemic conditions. Additionally, further studies are required to determine whether stable medication is actually a protective factor for OCD patients during pandemics in response to handwashing directives.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This research received no external funding.

References

2. Lewis D. COVID-19 rarely spreads through surfaces. So why are we still deep cleaning. Nature. 2021 Feb 4;590(7844):26-8.

3. Wang CC, Prather KA, Sznitman J, Jimenez JL, Lakdawala SS, Tufekci Z, et al. Airborne transmission of respiratory viruses. Science. 2021 Aug 27;373(6558):eabd9149.

4. Arienzo A, Gallo V, Tomassetti F, Pitaro N, Pitaro M, Antonini G. A narrative review of alternative transmission routes of COVID 19: what we know so far. Pathogens and Global Health. 2023 Jun 25:1-15.

5. Kwiatkowska A, Granicka LH. Anti-Viral Surfaces in the Fight against the Spread of Coronaviruses. Membranes. 2023 Apr 27;13(5):464.

6. Goldman E. SARS Wars: the fomites strike back. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2021 Jun 11;87(13):e00653-21.

7. Marsalek J. Reframing the problem of the fomite transmission of COVID-19. Journal of Hospital Infection. 2021 Sep 1;115:133-4.

8. Cheng P, Luo K, Xiao S, Yang H, Hang J, Ou C, et al. Predominant airborne transmission and insignificant fomite transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in a two-bus COVID-19 outbreak originating from the same pre-symptomatic index case. Journal of hazardous materials. 2022 Mar 5;425:128051.

9. Jimenez JL, Marr LC, Randall K, Ewing ET, Tufekci Z, Greenhalgh T, et al. What were the historical reasons for the resistance to recognizing airborne transmission during the COVID-19 pandemic?. Indoor Air. 2022 Aug;32(8):e13070.

10. Nembhard MD, Burton DJ, Cohen JM. Ventilation use in nonmedical settings during COVID-19: Cleaning protocol, maintenance, and recommendations. Toxicology and industrial health. 2020 Sep;36(9):644-53.

11. Morawska L, Tang JW, Bahnfleth W, Bluyssen PM, Boerstra A, Buonanno G, et al. How can airborne transmission of COVID-19 indoors be minimised?. Environment international. 2020 Sep 1;142:105832.

12. World Health Organization. (2020, 15 October). Handwashing an effective tool to prevent COVID-19, other diseases World Health Organization: South East Asia. https://www.who.int/southeastasia/news/detail/15-10-2020-handwashing-an-effective-tool-to-prevent-covid-19-other-diseases

13. Rundle CW, Presley CL, Militello M, Barber C, Powell DL, Jacob SE, et al. Hand hygiene during COVID-19: recommendations from the American Contact Dermatitis Society. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2020 Dec 1;83(6):1730-7.

14. Parida SP, Bhatia V. Handwashing: a household social vaccine against COVID 19 and multiple communicable diseases. Int J Res Med Sci. 2020 Jul;8(7):2708.

15. Kaçar AŞ. Obsessive-compulsive disorder during and after Covid-19 pandemic. In Moustafa AA, editor. Mental Health Effects of COVID-19. London: Academic Press; 2021. pp. 171-84.

16. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®). Washington, DC, U.S.A.: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

17. Van Ameringen M, Patterson B, Turna J, Lethbridge G, Bergmann CG, Lamberti N, et al. Obsessive-compulsive disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of psychiatric research. 2022 May;149:114.

18. Dennis D, Radnitz C, Wheaton MG. A perfect storm? Health anxiety, contamination fears, and COVID-19: lessons learned from past pandemics and current challenges. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy. 2021 Sep;14:497-513.

19. Abba-Aji A, Li D, Hrabok M, Shalaby R, Gusnowski A, Vuong W, et al. COVID-19 pandemic and mental health: prevalence and correlates of new-onset obsessive-compulsive symptoms in a Canadian province. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020 Oct;17(19):6986.

20. Fiaschè F, Kotzalidis GD, Alcibiade A, Del Casale A. Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Psychiatry International. 2023 Apr 21;4(2):102-4.

21. Taher TM, Al-fadhul SA, Abutiheen AA, Ghazi HF, Abood NS. Prevalence of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) among Iraqi undergraduate medical students in time of COVID-19 pandemic. Middle East Current Psychiatry. 2021 Dec;28(1):1-8.

22. Hassan SM, Ring A, Tahir N, Gabbay M. The impact of COVID-19 social distancing and isolation recommendations for Muslim communities in North West England. BMC Public Health. 2021 Apr 28;21(1):812.

23. Malas O, Tolsá MD. The COVID-19 Pandemic and the Obsessive-Compulsive Phenomena, in the General Population and among OCD Patients: A Systematic Review. European Journal of Mental Health. 2022 Oct 18;17(2):132-48.

24. Jassi A, Shahriyarmolki K, Taylor T, Peile L, Challacombe F, Clark B, et al. OCD and COVID-19: a new frontier. The Cognitive Behaviour Therapist. 2020;13:e27.

25. Jain A, Bodicherla KP, Bashir A, Batchelder E, Jolly TS. COVID-19 and obsessive-compulsive disorder: the nightmare just got real. The primary care companion for CNS disorders. 2021 Mar 18;23(2):29372.

26. El Othman R, Touma E, El Othman R, Haddad C, Hallit R, Obeid S, et al. COVID-19 pandemic and mental health in Lebanon: a cross-sectional study. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice. 2021 Jun 1;25(2):152-63.

27. Samuels J, Holingue C, Nestadt PS, Bienvenu OJ, Phan P, Nestadt G. Contamination-related behaviors, obsessions, and compulsions during the COVID-19 pandemic in a United States population sample. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2021 Jun 1;138:155-62.

28. Darvishi E, Golestan S, Demehri F, Jamalnia S. A cross-sectional study on cognitive errors and obsessive-compulsive disorders among young people during the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019. Activitas Nervosa Superior. 2020 Dec;62:137-42.

29. Alateeq DA, Almughera HN, Almughera TN, Alfedeah RF, Nasser TS, Alaraj KA. The impact of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic on the development of obsessive-compulsive symptoms in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Medical Journal. 2021 Jul;42(7):750-60.

30. Bibawy D, Barco J, Sounboolian Y, Atodaria P. A Case of New-Onset Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Schizophrenia in a 14-Year-Old Male following the COVID-19 Pandemic. Case Reports in Psychiatry. 2023 Jun 10;2023:1789546.

31. Costa A, Jesus S, Simões L, Almeida M, Alcafache J. A Case of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Triggered by the Pandemic. Psych. 2021 Dec 14;3(4):890-6.

32. Dar SA, Dar MM, Sheikh S, Haq I, Azad AM, Mushtaq M, et al. Psychiatric comorbidities among COVID-19 survivors in North India: A cross-sectional study. Journal of education and health promotion. 2021;10:309.

33. Hezel DM, Rapp AM, Wheaton MG, Kayser RR, Rose SV, Messner GR, et al. Resilience predicts positive mental health outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic in New Yorkers with and without obsessive-compulsive disorder. Journal of psychiatric research. 2022 Jun 1;150:165-72.

34. Perkes IE, Brakoulias V, Lam-Po-Tang J, Castle DJ, Fontenelle LF. Contamination compulsions and obsessive-compulsive disorder during COVID-19. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2020 Nov;54(11):1137-8.

35. Chakraborty A, Karmakar S. Impact of COVID-19 on obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). Iranian journal of psychiatry. 2020 Jul;15(3):256-9.

36. Brewer G, Centifanti L, Caicedo JC, Huxley G, Peddie C, Stratton K, et al. Experiences of mental distress during COVID-19: Thematic analysis of discussion forum posts for anxiety, depression, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Illness, Crisis & Loss. 2022 Oct;30(4):795-811.

37. Sharma LP, Balachander S, Thamby A, Bhattacharya M, Kishore C, Shanbhag V, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the short-term course of obsessive-compulsive disorder. The Journal of nervous and mental disease. 2021 Apr 1;209(4):256-64.

38. Gokhale MV, Chakole S. A Review of Effects of Pandemic on the Patients of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Cureus. 2022 Oct 24;14(10):e30628.

39. Fang A, Berman NC, Hoeppner SS, Wolfe EC, Wilhelm S. State and Trait Risk and Resilience Factors Associated with COVID-19 Impact and Obsessive–Compulsive Symptom Trajectories. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy. 2021 Dec 1:190.

40. Liao J, Liu L, Fu X, Feng Y, Liu W, Yue W, et al. The immediate and long-term impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder: A one-year follow-up study. Psychiatry research. 2021 Dec 1;306:114268.

41. Munk AJ, Schmidt NM, Alexander N, Henkel K, Hennig J. Covid-19—Beyond virology: Potentials for maintaining mental health during lockdown. PloS one. 2020 Aug 4;15(8):e0236688.

42. Vinkers CH, van Amelsvoort T, Bisson JI, Branchi I, Cryan JF, Domschke K, et al. Stress resilience during the coronavirus pandemic. European Neuropsychopharmacology. 2020 Jun 1;35:12-6.

43. Kuckertz JM, Van Kirk N, Alperovitz D, Nota JA, Falkenstein MJ, Schreck M, et al. Ahead of the curve: responses from patients in treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder to coronavirus disease 2019. Frontiers in Psychology. 2020 Oct 27;11:572153.

44. Cludius B, Mannsfeld AK, Schmidt AF, Jelinek L. Anger and aggressiveness in obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) and the mediating role of responsibility, non-acceptance of emotions, and social desirability. European archives of psychiatry and clinical neuroscience. 2021 Sep;271:1179-91.

45. Liu L, Liu C, Zhao X. Mapping the paths from styles of anger experience and expression to obsessive–compulsive symptoms: the moderating roles of family cohesion and adaptability. Frontiers in Psychology. 2017 May 2;8:671.

46. Alonso P, Bertolín S, Segalàs J, Tubío-Fungueiriño M, Real E, Mar-Barrutia L, et al. How is COVID-19 affecting patients with obsessive–compulsive disorder? A longitudinal study on the initial phase of the pandemic in a Spanish cohort. European Psychiatry. 2021;64(1):e45.

47. Benatti B, Albert U, Maina G, Fiorillo A, Celebre L, Girone N, et al. What happened to patients with obsessive compulsive disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic? A multicentre report from tertiary clinics in northern Italy. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2020 Jul 21;11:720.

48. Nissen JB, Højgaard DR, Thomsen PH. The immediate effect of COVID-19 pandemic on children and adolescents with obsessive compulsive disorder. BMC psychiatry. 2020 Dec;20(1):511.

49. Wheaton MG, Ward HE, Silber A, McIngvale E, Björgvinsson T. How is the COVID-19 pandemic affecting individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) symptoms?. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2021 Jun 1;81:102410.

50. Demaria F, Pontillo M, Di Vincenzo C, Di Luzio M, Vicari S. Hand Washing: When Ritual Behavior Protects! Obsessive–Compulsive Symptoms in Young People during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Narrative Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2022 Jun 2;11(11):3191.

51. Ornell F, Braga DT, Bavaresco DV, Francke ID, Scherer JN, von Diemen L, et al. Obsessive-compulsive disorder reinforcement during the COVID-19 pandemic. Trends in psychiatry and psychotherapy. 2021 Jan 22;43:81-4.

52. de Jesus S, Costa AL, Almeida M, Garrido P, Alcafache J. Conradi-Hünerman-Happle Syndrome and Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder: a clinical case report. BMC psychiatry. 2023 Dec;23(1):87.

53. Mushtaq H, Singh S, Mir M, Tekin A, Singh R, Lundeen J, et al. The well-being of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a narrative review. Cureus. 2022 May 17;14(5):e25065.

54. D’Urso G, Magliacano A, Dell’Osso B, Lamberti H, Luciani A, Mariniello TS, et al. Effects of strict COVID-19 lockdown on patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder compared to a clinical and a nonclinical sample. European Psychiatry. 2023 Jan;66(1):e45.

55. Sulaimani MF, Bagadood NH. Implication of coronavirus pandemic on obsessive-compulsive-disorder symptoms. Reviews on environmental health. 2021 Mar 26;36(1):1-8.

56. Kumar A, Somani A. Dealing with Corona virus anxiety and OCD. Asian journal of psychiatry. 2020 Jun 1;51:102053.

57. Shafran R, Coughtrey A, Whittal M. Recognising and addressing the impact of COVID-19 on obsessive-compulsive disorder. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2020 Jul 1;7(7):570-2.

58. Kumar A, Nayar KR. COVID 19 and its mental health consequences. Journal of Mental Health. 2021 Jan 2;30(1):1-2.

59. Hassoulas A, Umla-Runge K, Zahid A, Adams O, Green M, Hassoulas A, et al. Investigating the association between obsessive-compulsive disorder symptom subtypes and health anxiety as impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. Psychological reports. 2022 Dec;125(6):3006-27.

60. Matsunaga H, Mukai K, Yamanishi K. Acute impact of COVID-19 pandemic on phenomenological features in fully or partially remitted patients with obsessive–compulsive disorder. Psychiatry and clinical neurosciences. 2020 Oct;74(10):565-6.

61. Linde ES, Varga TV, Clotworthy A. Obsessive-compulsive disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic—a systematic review. Frontiers in psychiatry. 2022 Mar 25;13:806872.

62. Quittkat HL, Düsing R, Holtmann FJ, Buhlmann U, Svaldi J, Vocks S. Perceived impact of Covid-19 across different mental disorders: a study on disorder-specific symptoms, psychosocial stress and behavior. Frontiers in psychology. 2020 Nov 17;11:586246.

63. French I, Lyne J. Acute exacerbation of OCD symptoms precipitated by media reports of COVID-19. Irish journal of psychological medicine. 2020 Dec;37(4):291-4.

64. Sahoo S, Bharadwaj S, Mehra A, Grover S. COVID-19 as a “nightmare” for persons with obsessive-compulsive disorder: A case report from India. Journal of Mental Health and Human Behaviour. 2020 Jul 1;25(2):146-8.

65. Maye CE, Wojcik KD, Candelari AE, Goodman WK, Storch EA. Obsessive compulsive disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic: A brief review of course, psychological assessment and treatment considerations. Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders. 2022 Apr 1;33:100722.

66. Berman NC, Fang A, Hoeppner SS, Reese H, Siev J, Timpano KR, et al. COVID-19 and obsessive-compulsive symptoms in a large multi-site college sample. Journal of obsessive-compulsive and related disorders. 2022 Apr 1;33:100727.

67. Davide P, Andrea P, Martina O, Andrea E, Davide D, Mario A. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on patients with OCD: Effects of contamination symptoms and remission state before the quarantine in a preliminary naturalistic study. Psychiatry research. 2020 Sep 1;291:113213.

68. Cunning C, Hodes M. The COVID-19 pandemic and obsessive–compulsive disorder in young people: Systematic review. Clinical child psychology and psychiatry. 2022 Jan;27(1):18-34.

69. Jalal B, Chamberlain SR, Robbins TW, Sahakian BJ. Obsessive–compulsive disorder—contamination fears, features, and treatment: Novel smartphone therapies in light of global mental health and pandemics (COVID-19). CNS spectrums. 2022 Apr;27(2):136-44.

70. Sowmya AV, Singh P, Samudra M, Javadekar A, Saldanha D. Impact of COVID-19 on obsessive-compulsive disorder: A case series. Industrial Psychiatry Journal. 2021 Oct;30(Suppl 1):S237.

71. Jelinek L, Moritz S, Miegel F, Voderholzer U. Obsessive-compulsive disorder during COVID-19: Turning a problem into an opportunity?. Journal of anxiety disorders. 2021 Jan 1;77:102329.

72. Grant JE, Drummond L, Nicholson TR, Fagan H, Baldwin DS, Fineberg NA, et al. Obsessive-compulsive symptoms and the Covid-19 pandemic: A rapid scoping review. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2022 Jan 1;132:1086-98.

73. Siddiqui M, Wadoo O, Currie J, Alabdulla M, Al Siaghy A, AlSiddiqi A, et al. The Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Individuals With Pre-existing Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder in the State of Qatar: An Exploratory Cross-Sectional Study. Frontiers in psychiatry. 2022 Apr 12;13:833394.

74. Damirchi ES, Mojarrad A, Pireinaladin S, Grjibovski AM. The role of self-talk in predicting death anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and coping strategies in the face of coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Iranian journal of psychiatry. 2020 Jul;15(3):182-8.

75. Silva Moreira P, Ferreira S, Couto B, Machado-Sousa M, Fernández M, Raposo-Lima C, et al. Protective elements of mental health status during the COVID-19 outbreak in the Portuguese population. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021 Feb;18(4):1910.

76. Zaccari V, D'Arienzo MC, Caiazzo T, Magno A, Amico G, Mancini F. Narrative review of COVID-19 impact on obsessive-compulsive disorder in child, adolescent and adult clinical populations. Frontiers in psychiatry. 2021 May 13;12:575.

77. Neal T, Lienert P, Denne E, Singh JP. A general model of cognitive bias in human judgment and systematic review specific to forensic mental health. Law and human behavior. 2022 Apr;46(2):99-120.