Abstract

Mental health telephone helplines serve as vital access points for individuals experiencing psychological distress, offering immediate, anonymous support from crisis interventionists and resource specialists. While widely accessed globally, limited research exists on the demographic characteristics and help-seeking behaviors of helpline users, particularly outside the United States and within racially marginalized or culturally specific communities. This study begins to address that gap through a secondary content analysis of caller data collected between 2018 and 2023 by Sikh Your Mind, a UK-based mental health nonprofit serving Punjabi Sikh populations. Findings suggest that the primary difficulty identified by the 538 calls was due to mood dysregulation (33.8%) and relationship difficulties (23.6%). Further findings in relation to caller demographics and outcomes of helpline engagement are detailed alongside limitations and future research.

Keywords

Punjabi, Sikh, Cultural, Helpline, Community mental health, Help seeking behavior, South Asian

Introduction

Mental health support and care is needed beyond formal clinical settings. Telephone helplines have gained popularity amongst help seeking individuals for their convenience, accessibility, and range [1]. Historically, telephone helplines have shown to be effective in reducing suicide rates and decreasing overall mental health symptoms [2], supporting and empowering callers to foster a sense of control and connecting users to proper social support and outpatient resources [3].

Traditionally, the aim of mental health helplines is to provide individuals with immediate support for common (e.g. depression and anxiety) to severe (e.g. psychosis, bipolar disorder) mental health presentations, isolation, abuse, and crisis intervention. Boness, Helle and Logan [4] shared that telephone helplines allow callers to remain anonymous which reduces psychological barriers which may occur whilst seeking help. This can be particularly beneficial for those who feel reluctant to seek guidance on sensitive issues such as abuse or sexuality [5].

Effectiveness of telephone helplines

The National Institute for Mental Health [6] reported the underutilization of mental health support services by people of color whilst the Department of Health [7] highlight the need for services and information to ethnic minority communities. Consequently, considering access and provision of mental health helplines will be necessary. Ahmed, Cosgrove and Craig [8] highlight in their systematic review, that whilst a number of helplines exist for minority communities including the Muslim Youth helpline, the Muslims Women helpline, and the Asian Child Protection helpline (all in the UK), research on the effectiveness of mental health helplines is limited [9]. They also uncovered that ethnic minority groups were less aware of helplines that were available and less likely to use them for support than their white counterparts. Trust and confidentiality were also described as reasons for lower levels of uptake.

Studies however have shown that callers report positive outcomes especially with services providing out of hours support and reduced levels of psychological distress shortly after accessing the helpline [10]. This research has predominantly focused on the types of callers, frequency and trends over time [11]. However, there are limited studies that focus on more in-depth demographic analyses [12,13] and the distinction between the reasons for calling and victimization (domestic violence, alcohol abuse, suicidality). Furthermore, most mental health helpline research is based primarily in the United States of America, with little to no international reporting [9,14,15]. This makes it difficult to accurately capture the nature of callers, their needs, and usage in other areas of the world and across community groups.

Acknowledging the needs of a helpline user and their identities is important to ensure the integrity, quality and satisfaction of care provided [3]. Research demonstrates that incorporating facets of a caller’s identity, such as faith and culture, in therapeutic settings is synonymous with improving patient recovery rates [16,17], yet no known data exists on the South Asian community’s use of helplines [3].

South Asians

The term South Asian includes a diverse set of communities including but not restricted to those Pakistan, Nepal, Sri Lanka, India, etc. and each with its own religion, language, political and socioeconomic history and health needs [18]. This paper aims to focus on considering Punjabi Sikhs to consider their specific mental health support needs.

Who are Sikhs?

Sikhi is the fifth-largest religion in the world, with around 25-30 million followers globally. Sikhs are followers of Sikhi, a monotheistic religion that originated in the Punjab region of India in the 15th century. Founded by Guru Nanak and shaped by ten successive Gurus. The current living Guru of the Sikhs is Sri Guru Granth Sahib Ji [19].

Sikh your Mind (SYM) is a national mental health charity founded in 2005 and provides several services to the Punjabi Sikh community in the UK [3]. One of the services includes a telephone helpline which aims to provide a confidential space for individuals to access support for their mental health and wellbeing needs. The helpline is open between 7 pm and 9 pm every evening 365 days a year. This paper aims to offer descriptive analysis into the calls and callers that used this telephone helpline to consider further the demographic characteristics and patterns of service use among callers to a Punjabi Sikh mental health helpline.

Whilst research considering the Punjabi Sikh community and their use of mental health services are on the rise [20–22], to the authors’ knowledge there has been no research published on the use of a telephone mental health helpline for the Punjabi Sikh community.

Ethical considerations

This paper used secondary data, as although the data were not intended for research use at the time of each call, callers were made aware of General Data Protection Regulations and callers were aware that information about calls would be anonymously stored by the charity in compliance with ethical standards [23]. This aligns with established guidelines that exempt certain types of research involving de-identified information from IRB oversight [24]. Trail et al. [13] wrote about the challenges of informed consent in helpline settings and encouraged the use of a waiver of consent in research that involves low risk, where it is impracticable to obtain more formal consent and there is sufficient protection of confidentiality and anonymity.

Method

This descriptive study was conducted as a content analysis on secondary data which was gathered during the operating hours of the SYM telephone helpline. Data were collected on a password protected shared drive where telephone call handlers input callers details whilst ensuring anonymity. Researchers focused on collating information such as age, gender and location, the reason for the call, outcome as well as any safeguarding concerns.

Data collection

Reliability coding protocol was established across three of the authors of this paper (HM, AK, and GK). The reason for coding was due to the fact that the database that call handlers input caller information into invited open ended columns e.g. presentation and outcome (as two examples) allowing them to enter as much or as little information about the conversation with callers. To ensure the data were analyzable, researchers worked to systematically conceptualize these responses into clear, defined categories and themes.

Inter-rater reliability between researchers was considered and any discrepancies in coding were reviewed and resolved with regular meetings alongside coding.

Demographic information was gathered both through self-disclosure and direct questioning to obtain a clearer understanding of the calls' context and nature. All of the data across the 5 years has been included in this write up however it is important to note that a proportion of callers did not wish to disclose specific details about themselves.

Results

There were 538 participants who accessed the SYM telephone helpline support from 2018 to 2023. The number of callers from one year to another was very similar, approximately equating to 100 callers each year. Descriptive statistics highlight users of the helpline including their age, gender, location, religion, current concerns/difficulty as well as the outcome following the call. Statistical analysis such as chi squared analysis were not undertaken due to the low frequency (less than 5 per response) in some of the cells e.g. data collection categories among callers who utilized the mental health telephone helpline service [25]. Furthermore, the aim of this paper is to describe frequencies and prevalence rather than to test hypotheses which is especially pertinent given the lack of existing data in this area. The authors hope that descriptive data as the first step in this area may also offer greater accessibility to the community it serves [26].

Table 1 below represents the demographic characteristics of callers. Additionally, Figures 1–4 examine key contextual factors, including the primary reasons for contacting the service, the outcomes of these interactions, and whether the caller was seeking support for themselves or on behalf of someone else. Furthermore, any safeguarding concerns identified during the calls are highlighted, offering insight into potential risks that callers presented with on the helpline.

|

Demographic Characteristics |

n |

% |

|

Gender |

||

|

Female |

237 |

44.0 |

|

Male |

226 |

42.0 |

|

Unknown |

75 |

13.9 |

|

Age |

||

|

13–17 |

4 |

0.7 |

|

18–25 |

52 |

9.7 |

|

26–40 |

77 |

14.3 |

|

41–55 |

80 |

14.9 |

|

56–70 |

14 |

2.6 |

|

70+ |

3 |

0.6 |

|

Religion |

||

|

Atheist |

1 |

0.2 |

|

Christian |

1 |

0.2 |

|

Hindu |

2 |

0.4 |

|

Muslim |

2 |

0.4 |

|

Sikh |

362 |

67.3 |

|

Unknown |

170 |

31.6 |

|

Location |

||

|

America |

11 |

2.0 |

|

Anglia |

10 |

1.9 |

|

Australia |

1 |

0.2 |

|

Canada |

4 |

0.7 |

|

East Midlands |

31 |

5.8 |

|

Germany |

1 |

0.2 |

|

India |

4 |

0.7 |

|

London |

89 |

16.5 |

|

Mauritius |

2 |

0.4 |

|

North-west England |

7 |

1.3 |

|

Scotland |

1 |

0.2 |

|

South-East England |

33 |

6.1 |

|

South-West England |

4 |

0.7 |

|

United Kingdom |

16 |

3.0 |

|

Wales |

2 |

0.4 |

|

West Midlands |

201 |

37.4 |

|

Yorkshire |

17 |

3.2 |

|

Unknown |

104 |

19.3 |

|

Note. MH is an abbreviation for mental health. |

||

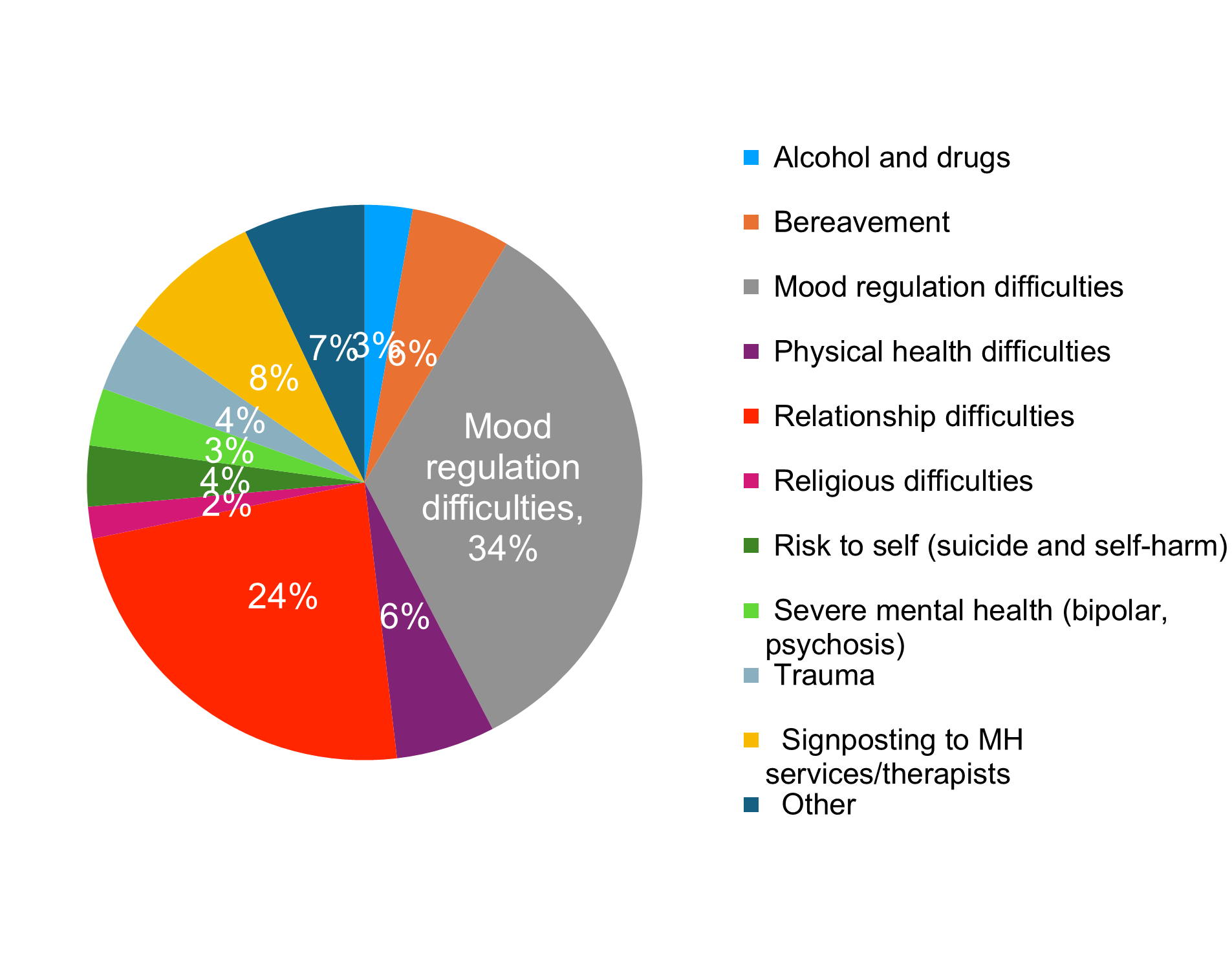

Figure 1. Reasons for contacting the SYM helpline.

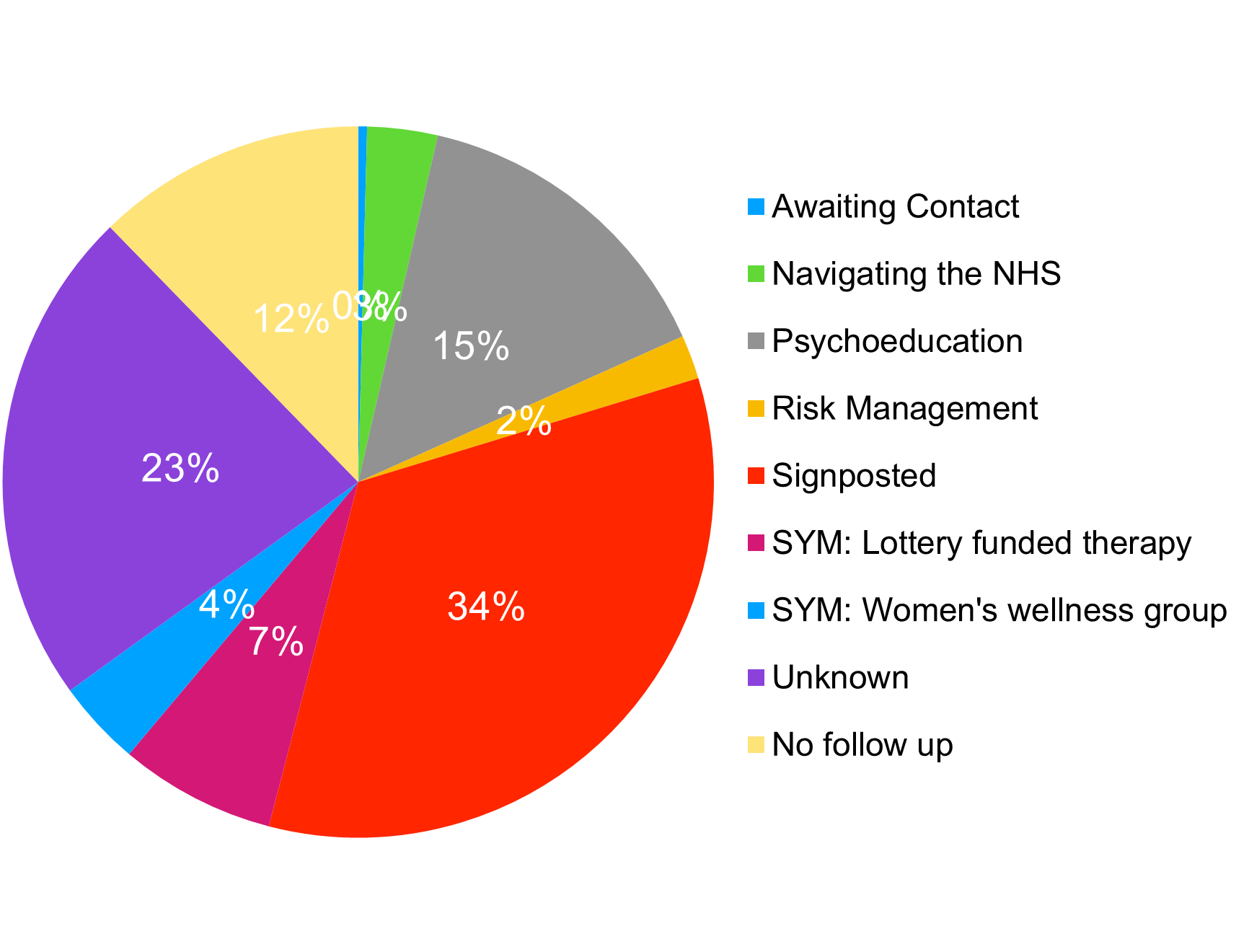

Figure 2. Outcomes and signposting following telephone helpline use.

Figure 3. Who the call was about.

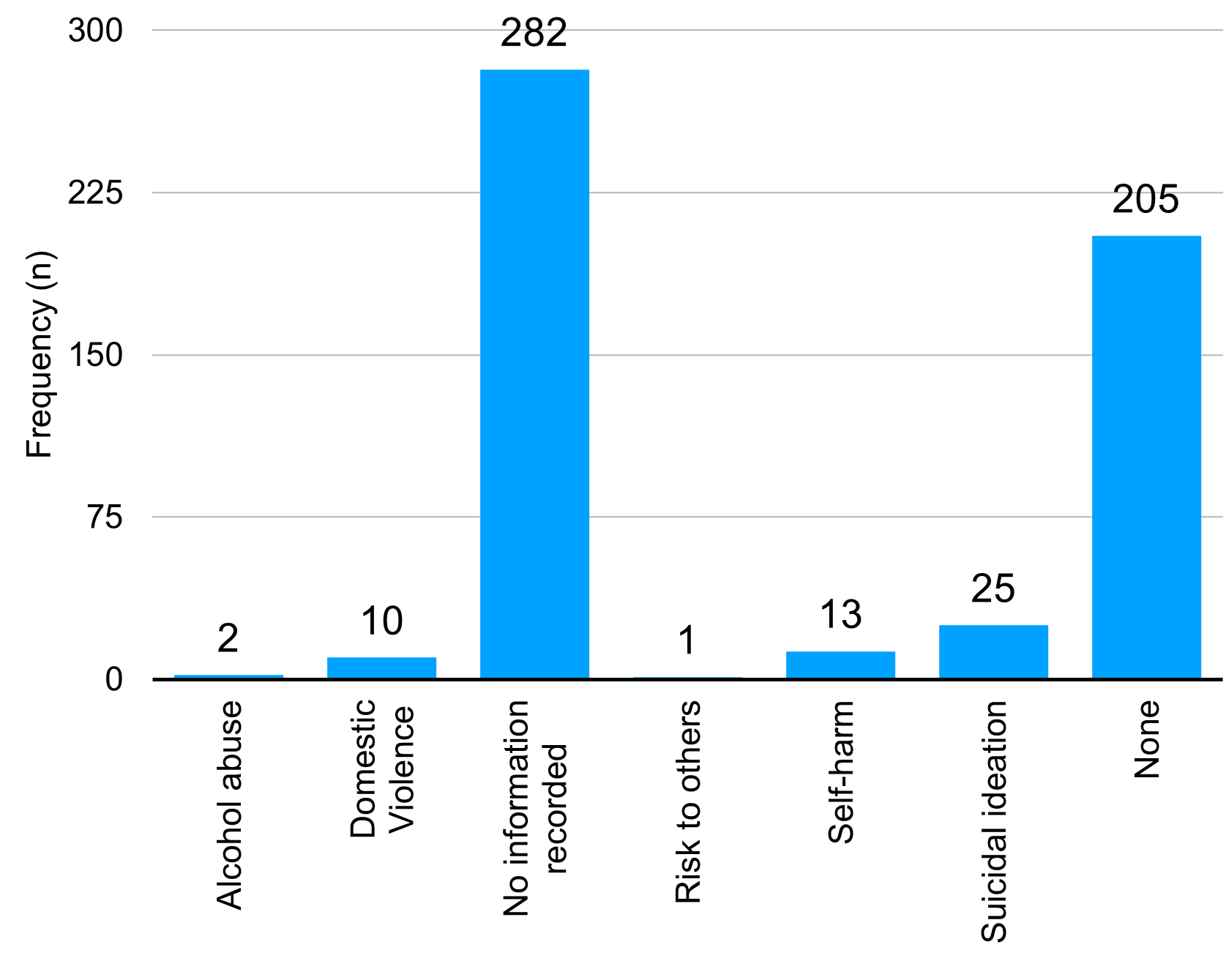

Figure 4. Safeguarding concerns.

Age & gender

The age categories were divided into 13–17 year olds (adolescents), 18–25 years old (young adults), 26–40 (adults), 41–55 (middle-aged), 55–70 (older adults), 70+ (elderly), 80+ (very elderly), and unknown with the largest groups being unknown (n=308), 41–55 (n=80), and 26–40 (n=77). Many callers were females (n=237), followed closely by male callers (n=226).

Religion

Most callers identified as Sikh (67.3%), while 31.6% of callers' religion was unknown. A smaller proportion of callers identified with other religions, including Christian, Hindu, and Muslim.

Location

The West Midlands had the highest number of calls (201), followed by London (89) and South-East England (33). A significant number of callers' locations were unknown (104). Interestingly, whilst Sikh your Mind is a UK charity, calls were also received from Europe and America. Whilst most calls were made from within the UK there were 21 calls made from outside of the UK and were also included in the paper for transparency purposes.

The most common presenting issue was mood regulation difficulties (33.8%), followed by relationship difficulties (23.6%). Interestingly religious difficulties (2%) and alcohol and drugs (3%) were the least common reasons for calling the helpline.

Individuals on the helpline were most commonly offered signposting information (33.6%) following their call, which included referrals to various services, both statutory and non-statutory such as NHS Talking Therapies (formerly known as IAPT) in the NHS, private therapy provision as well as national charities such as MIND, Relate, Age Concern, Citizen’s Advice Bureau and Autism services. Navigating the NHS represents conversations that were had with callers around statutory service provision that was available for free for their psychological and mental health care needs. The numbers of callers recommended to engage with SYM services including The National Lottery funded therapy and the Women’s wellness groups was due to funding being obtained in 2020 and being available for a time limited duration for the former. The Women’s wellness group continues to be available now and is an ongoing support group for women in the community which incorporates Sikhi, meditation, breathwork and sangat (spiritual congregation).

To help understand the context of the call, information about who the caller was seeking support for was recorded. However, this information was not systematically captured for most calls (n=244).

Safeguarding involves protecting individuals from harm, abuse, or neglect, particularly those who are vulnerable. It includes identifying risks and taking steps to ensure their safety. The safeguarding data indicates that more than half of the records (52.4%) had no information recorded. Among the remaining cases, the most frequently reported concerns were related to suicidality (4.6%, n=25).

Discussion

The results of this descriptive and longitudinal study provide an overview of the types of calls and callers that accessed the SYM helpline over a 5 year time period. Prior to considering the results further, it is important to acknowledge that the helpline was (and continues to be) volunteer led and only open 2 hours every day. This is likely to be one of many factors that impacted on the number of calls received, recognizing that there were only 100 calls (on average) per year. A systematic review conducted by Hoffberg et al. [27] that high quality evidence demonstrating the use of helplines is lacking, however uncontrolled studies indicate the positive effect of helplines. Whilst it is also clear that not all the information was collected systematically for all callers, this paper aimed to disseminate and make transparent the use of this mental health helpline in the Punjabi Sikh community.

Reason for calling

There are several findings worth considering further including the primary difficulty identified by callers being around mood dysregulation (33.8%) and relationship difficulties (23.6%). It is helpful to share that mood dysregulation in this study included difficulties with anxiety, low mood, low self-esteem, anger (as a few examples). Mood regulation and relationship difficulties are often considered as common mental health difficulties in the UK, that are appropriate for primary care support provided by GPs or NHS Talking Therapies [28] hence the onward signposting recommended to these services. Whilst research indicates that individuals from racially minoritized communities struggle to access these services and that culturally competent care and community engagement is required to increase engagement [29] the lack of more culturally sensitive options, especially when The National Lottery funding provided to SYM for counselling and therapy ended, was limited. In addition, it is important to note that callers were often unaware that these services existed within the NHS and often required self-referral only rather than needing to speak to a gatekeeper such as a GP. This is evident in the narrative not ‘hard to reach’ but ‘easy to ignore’ when considering the accessibility of mental health services for racially minoritized communities [30].

In addition, the smallest number of calls were due to religious, and alcohol and drugs related difficulties. Interestingly, Moreno, Bartkowoski and Xu [31] concluded that people who hold more conservative religious beliefs are more likely to access support from religious sources rather than mental health services which may explain the lack of religious difficulties as a presenting concern. Kaur [32] published a systematic review around alcohol addiction in the Sikh community and as well as stigma and religion, discovered that over reliance on a medical model of treatment over therapy was one of the main barriers in accessing support.

Impact of COVID-19

Furthermore, it is important to note that during the timeline of data collection (2018 to 2023) for this study there was a significant stressor for the world, namely the COVID-19 pandemic. Unsurprisingly, racialized communities consistently experienced worse mental health including higher rates of depression, anxiety and loneliness as well as lower life satisfaction [33] during this time. It will be necessary to compare this with future datasets from the helpline to consider whether difficulties for helpline users remain the same or change over time. Turkington et al. [34] suggests that communities relied on the Samaritans helpline even more during COVID-19 due to an increased sense of isolation and worsening mental health. Interestingly, however Kaur and Basra [35] concluded that whilst Sikh participants did struggle to adjust during the pandemic, they coped by making meaningful connections and linking up with the Gurdware to promote collective healing. In support of this, Stepanova et al. [36] considered the interactions between ethnic minorities and mental health services and found that individuals preferred wider community support even though it was not specifically targeted around mental health. This may be pertinent to SYM, particularly around how existing community resources can include mental health support alongside rather than a separate service. As an example, Hartwig and Mason [37] found that refugee and immigrants in the US expressed physical and emotional benefits from gardening as a meaningful health intervention.

Gender

Other findings include the relatively equal number of men and women who called the SYM helpline. Interestingly, other studies focusing on mental health seeking behaviors and gender have found that men are less likely to seek mental health support in comparison to women [38] even in a helpline context where anonymity is offered. Olaniyan [39] however found that, across genders, racial and ethnic minority students were less likely to use formal mental health services and suggested more reliance on informal or anonymous support. Interestingly, MPower, a mental health helpline in India reported a 126% increase in calls across 4 years suggesting an increasing willingness among men to engage in mental health support. There has been considerable variability in the reporting of which gender is more willing to seek support. Guney et al. [40] considered depression in males and females in Turkey and found inconclusive results requiring further research.

Age

A further finding in this paper highlights that most callers were between the age of 41 to 55, followed by ages 26 to 40. There were much fewer younger and older adult callers. During COVID-19, 63% of total calls to helplines across 19 countries were made by 30 to 60 year olds [14]. Sikh your Mind has a significant social media following which may account for the age groups that did use the helpline. In support, Statista [41] found that 40% of social media users in the UK were aged between 30 to 49 years old compared to 31% of 50+ and 24% between 18–29 years old. Tam et al., [42] found that social media mental health awareness campaigns were associated with positive changes in help seeking behaviors. Franks and Medforth [43] found that a blanket approach to advertising was not appropriate according to focus groups of participants from several different ethnic backgrounds. For younger participants, advertising in schools was preferred over public spaces. Furthermore, Neale et al. [44] reported that trust was a significant factor in accessing help and support and that younger members of the community preferred to ignore, resolve or keep the problem to themselves and would only contact organizations if there was no support available within their network or that the organization was trusted and known to others within their network. Bhui et al. [45] also reported that trust can be enhanced by support services when staff and patients are from the same groups which is the case within SYM.

Franks and Medforth [43] also reported that young people would prefer to talk to other young people and that organizations such as the Muslim Youth Helpline advertise their call handler volunteers as such. When considering older adults lack of engagement further, differing health beliefs, and language barriers were concluded as part of Teo et al.’s [46] scoping review. Werner and Karnieli [47] suggested that technology anxiety and patient - GP relationship can reduce the uptake of telephone support in older adults. Considering these themes further in the advertisement of the telephone helpline within the charity may be beneficial.

Location

Whilst social media is accessible to those worldwide, most callers were in London or the West Midlands. It is interesting to note that Sikh your Mind, whilst a national charity, has the greatest number of team members in both areas of the UK. According to the 2021 Census Sandwell a county in the West Midlands has the largest Sikh population in the UK [48]. London is the second area in the UK after the West Midlands with the largest number of Sikhs. This may indicate that the SYM helpline is effectively reaching the community it attempts to serve [49]. Interestingly, Curtis et al. [50] considered location and uptake of telephone based healthcare and found that there were higher in urban compared to rural areas of the UK, the latter of which are often made up of older populations.

Limitations, Future Research and Implications

This paper aimed to make transparent the types of calls and callers accessing the mental health helpline however there are several limitations worth considering. There were many missing entries during data collection from 2018 to 2023 and a lack of statistical analysis as a result. Given the general priority of helplines is to support callers in distress, data management has commonly been recorded as a secondary priority (Cassandra et al., 2020). However, recommendations for ongoing analysis, including conducting statistical tests such as chi-squared analysis to examine associations between variables, such as age/location of callers and reasons for calling) is recommended with future data sets. SYM has systematized the process of collecting data from callers since this paper was written. Furthermore, the charity has since made available an online chat service available via its website and hopes to publish further data around its usage. Text based mental health support has been seen as more accessible, anonymous, and convenient, particularly amongst young adults, which may be pertinent given the limited opening hours of the telephone helpline [51].

Given these findings, SYM will need to consider the advertisement of the helpline, to join up with statutory services as well as schools and other education establishments to promote the availability of culturally sensitive support for the community. Taylor Nelson Sofres Consumer [52] concluded that information about helplines would benefit from greater awareness in statutory and primary care organizations in order to support ethnic minority communities to access culturally sensitive support.

The authors of this paper also hope that other services, particularly mental health support services for racially minoritized communities consider publishing their data, regardless of data collection methods, given the paucity of literature in this area. Hardwicke et al. [53] reported that even if a dataset is limited or has lower methodological quality it is important to make it openly available to others to review, critique and build on for future improvement.

It is difficult to compare or draw further conclusions from this data given there is no data that exists for the use statutory or non-statutory services for this population. Future data collection may benefit from more detailed information about whether callers are first time users of mental health support when accessing the helpline.

Conflict of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Declaration Statement

Funding

This research did not receive specific funding, nor was it performed as part of employment of the authors. This was a nonprofit, voluntary based, research experience conducted by the authors for the sake of dissemination. There are no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Due to the anonymized data that was collected in compliance with ethical research standards, which does not allow for the identification of individual subjects, this study did not require a formal review by the Institutional Review Board (IRB). This decision aligns with established guidelines that exempt certain types of research involving de-identified information from IRB oversight.

Informed consent

Secondary data was used in this paper and was anonymized with focus on caller privacy and complaint with GDPR therefore explicit informed consent was not sought out.

Author contributions

All authors have contributed to data management, data analysis and write up of this paper.

Data availability statement

Supporting data can be requested if required.

References

2. Gu Y, Andargoli AE, Mackelprang JL, Meyer D. Design and implementation of clinical decision support systems in mental health helpline Services: A systematic review. International journal of medical informatics. 2024 Jun 1;186:105416.

3. Mann M, Kaur G. Amplifying Culturally Responsive Mental Health Support: Insights from a Sikh and Punjabi Community Helpline in the United Kingdom. Sikh Research Journal. 2025 Jun 30;10(1):3–24.

4. Boness CL, Helle AC, Logan S. Crisis line services: A 12?month descriptive analysis of callers, call content, and referrals. Health & social care in the community. 2021 May;29(3):738–45.

5. Latzer Y, Gilat I. Help-seeking characteristics of eating-disordered hotline callers: Community based study. Journal of Social Service Research. 2005 Mar 1;31(4):61–76.

6. National Institute for Mental Health in England. Engaging and Changing: Developing Effective policy for the care and treatment of Black and minority ethnic detained patients. London. Crown Copyright. 2003.

7. Department of Health. Delivering race equality in mental health care: A summary. London. 2025.

8. Ahmed K, Cosgrove E, Craig T. Considerations in the provision of mental health helpline services for minority ethnic groups: A systematic review. World Cultural Psychiatry Research Review. 2014;9(3):89–98.

9. Matthews S, Cantor JH, Brooks Holliday S, Eberhart NK, Breslau J, Bialas A, et al. Mental health emergency hotlines in the United States: A scoping review (2012–2021). Psychiatric Services. 2023 May 1;74(5):513–22.

10. Kitchingman TA, Caputi P, Woodward A, Wilson I, Wilson C. The impact of their role on telephone crisis support workers’ psychological wellbeing and functioning: Qualitative findings from a mixed methods investigation. Death Studies. 2025 Sep 14;49(8):998-1011.

11. Casquejo RK, de Jesus IP, dela Cerna SL, Nedamo JD, Pantaleon JA, Yabut HJ. The Call for Help: Exploring the Experiences of Mental Health Hotline Service Users. The Guidance Journal. 2023.

12. Dong CY. The uses of mental health telephone counselling services for Chinese speaking people in New Zealand: Demographics, presenting problems, outcome and evaluation of the calls. The New Zealand Medical Journal (Online). 2016 Sep 9;129(1441):68.

13. Trail, K., Baptiste, P., Hunt, T., and Brooks, A. (2022). Conducting Research in Crisis Helpline Settings: Common Challenges and Proposed Solutions. Crisis, 43, 263–69.

14. Brülhart M, Klotzbücher V, Lalive R, Reich SK. Mental health concerns during the COVID-19 pandemic as revealed by helpline calls. Nature. 2021 Dec 2;600(7887):121–6.

15. Singh S, Sagar R. Tele mental health helplines during the COVID-19 pandemic: Do we need guidelines? Asian Journal of Psychiatry. 2021 Nov 6; 67:102916.

16. Ayonrinde O. Importance of cultural sensitivity in therapeutic transactions: considerations for healthcare providers. Disease Management & Health Outcomes. 2003 Apr;11(4):233–48.

17. Bouwhuis-Van Keulen AJ, Koelen J, Eurelings-Bontekoe L, Hoekstra-Oomen C, Glas G. The evaluation of religious and spirituality-based therapy compared to standard treatment in mental health care: A multi-level meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychotherapy Research. 2024 Apr 2;34(3):339–52.

18. Uppal GK, Bonas S, Philpott H. Understanding and awareness of dementia in the Sikh community. Mental Health, Religion & Culture. 2014 Apr 21;17(4):400–14.

19. Kaur G. The use of the Sikh scriptures to promote psychological flexibility using acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT). Spirituality in Clinical Practice. 2025;12(3):399–406.

20. Malhi NK, Sidhu SS, Singh R, Singh MK. Sikh Tenets and Experiences That Relate to Mental Health and Well-Being. InEastern Religions, Spirituality, and Psychiatry: An Expansive Perspective on Mental Health and Illness. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland; 2024. pp. 151–66.

21. Nagashima S, Bedi RP, Mann G, Currie LN. A multiple case study analysis of clinical counseling or psychotherapy with Indian Punjabi Sikhs. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2025 Jan 2;56(1):84–94.

22. Stahre MK. Restricted entry: do Punjabi Sikhs have equal immediate access to counselling and psychotherapy services? Doctoral dissertation, University of British Columbia; 2023.

23. Tripathy JP. Secondary data analysis: Ethical issues and challenges. Iranian Journal of Public Health. 2013 Dec;42(12):1478–9.

24. Mehta P, Zimba O, Gasparyan AY, Seiil B, Yessirkepov M. Ethics committees: structure, roles, and issues. Journal of Korean Medical Science. 2023 Jun 26;38(25):e198.

25. McHugh ML. The chi-square test of independence. Biochemia medica. 2013 Jun 15;23(2):143–9.

26. Alabi O, Bukola T. Introduction to Descriptive statistics [Internet]. In: Recent Advances in Biostatistics. IntechOpen; 2023.

27. Hoffberg AS, Stearns-Yoder KA, Brenner LA. The effectiveness of crisis line services: a systematic review. Frontiers in Public Health. 2020 Jan 17; 7:399.

28. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Depression in adults: treatment and management. 2022. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng222.

29. Turin TC, Chowdhury N, Haque S, Rumana N, Rahman N, Lasker MA. Meaningful and deep community engagement efforts for pragmatic research and beyond: engaging with an immigrant/racialised community on equitable access to care. BMJ Global Health. 2021 Aug 1;6(8):e006370.

30. Lamb J, Bower P, Rogers A, Dowrick C, Gask L. Access to mental health in primary care: a qualitative meta-synthesis of evidence from the experience of people from ‘hard to reach’groups. Health: 2012 Jan;16(1):76–104.

31. Moreno AN, Bartkowski JP, Xu X. Religion and help-seeking: Theological conservatism and preferences for mental health assistance. Religions. 2022 May 5;13(5):415.

32. Kaur K. ‘Reputation, reputation, reputation! Oh, I have lost my reputation!’; A literature review on alcohol addiction in the British Sikh and/or Punjabi community and the barriers to accessing support. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2024 Mar;59(2):agad080.

33. Fancourt D, Steptoe A, Bradbury A. Tracking the psychological and social consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic across the UK population: Findings, impact and recommendations from the COVID-19 Social Study. London: UCL; 2022.

34. Turkington R, Mulvenna MD, Bond RR, O’Neill S, Potts C, Armour C, et al. Why do people call crisis helplines? Identifying taxonomies of presenting reasons and discovering associations between these reasons. Health Informatics Journal. 2020;26(4):2597–613.

35. Kaur G, Basra MK. COVID-19 and the Sikh Community in the UK: A Qualitative Study. Journal of Religion and Health. 2022 Jun;61(3):2302–18.

36. Stepanova E, Croke S, Yu G, Bífárìn O, Panagioti M, Fu Y. “I am not a priority”: ethnic minority experiences of navigating mental health support and the need for culturally sensitive services during and beyond the pandemic. BMJ Mental Health. 2025 Apr 24;28(1):1–8.

37. Hartwig KA, Mason M. Community gardens for refugee and immigrant communities as a means of health promotion. Journal of Community Health. 2016 Dec;41(6):1153–9.

38. Wagner AJ, Reifegerste D. Real men don't talk? Relationships among depressiveness, loneliness, conformity to masculine norms, and male non-disclosure of mental distress. SSM-Mental Health. 2024 Jun 1;5:100296.

39. Olaniyan FV. Paying the widening participation penalty: Racial and ethnic minority students and mental health in British universities. Analyses Social Issues Public Policy. 2021;21(1):761–83.

40. Güney E, Alkan Ö, Genç A, Kabaku? AK. Gambling behavior of husbands of married women living in Turkey and risk factors. Journal of Substance Use. 2023 May 4;28(3):466–72.

41. Stastica Search Department. Distribution of social network users in the UK by age group. Statista. 2024. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1239046/top-saas-countries-list/.

42. Tam MT, Wu JM, Zhang CC, Pawliuk C, Robillard JM. A systematic review of the impacts of media mental health awareness campaigns on young people. Health promotion practice. 2024 Sep;25(5):907–20.

43. Franks M, Medforth R. Young helpline callers and difference: exploring gender, ethnicity and sexuality in helpline access and provision. Child & Family Social Work. 2005 Feb;10(1):77–85.

44. Neale J, Worrell M, Randhawa G. Breaking down barriers to accessing mental health support services?a qualitative study among young South Asian and African?Caribbean communities in Luton. Journal of Public Mental Health. 2009 Sep 17;8(2):15–25.

45. Bhui K, Bhugra D, McKenzie K. Specialist services for minority ethnic groups? Institute of Psychiatry; 1999.

46. Teo K, Churchill R, Riadi I, Kervin L, Wister AV, Cosco TD. Help-seeking behaviors among older adults: a scoping review. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2022 May;41(5):1500–10.

47. Werner P, Karnieli E. A model of the willingness to use telemedicine for routine and specialized care. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare. 2003 Sep 1;9(5):264–72.

48. British Sikh Report. Sikhs in Census 2021: Summary report. 2022. Available at: https://britishsikhreport.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Sikhs-in-Census-2021-Summary.pdf.

49. Fawcett SB. Some values guiding community research and action. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1991;24(4):621–36.

50. Curtis ME, Clingan SE, Guo H, Zhu Y, Mooney LJ, Hser YI. Disparities in digital access among American rural and urban households and implications for telemedicine?based services. The Journal of Rural Health. 2022 Jun;38(3):512–8.

51. Pisani AR, Gould MS, Gallo C, Ertefaie A, Kelberman C, Harrington D, et al. Individuals who text crisis text line: Key characteristics and opportunities for suicide prevention. Suicide and Life?Threatening Behavior. 2022 Jun;52(3):567–82.

52. Taylor Nelson Sofres Consumer. Usage of and attitudes towards mental health helplines. Report prepared for mental health helplines partnership. 2002.

53. Hardwicke TE, Wallach JD, Kidwell MC, Bendixen T, Crüwell S, Ioannidis JP. An empirical assessment of transparency and reproducibility-related research practices in the social sciences (2014–2017). Royal Society Open Science. 2020 Feb 19;7(2):190806