Abstract

A long-standing question in clinical psychology concerns the merits and drawbacks of using diagnostic labels in communication about mental illness. A frequent view is that such labels contribute to mental illness stigma, for example by fostering a categorical view of affected people as part of a distinct out-group. Previous research has found some evidence to support such claims, but results are mixed. The current study investigates the effects of diagnostic labels at the level of specific behaviors, rather than subsuming them in a case vignette, in a sample of psychology undergraduates in Germany. Results indicate that when behaviors are presented along with a diagnostic label, participants perceive them as less common, less blameworthy and less typical for themselves, but not as less acceptable, normal or treatable. With a label, behaviors are also perceived as more indicative of a person dependent on outside help. These results held true for behaviors across both actual DSM-5 symptoms of mental illnesses and similar behaviors that were not genuine diagnostic criteria. Labeling effects were most pronounced among symptoms of schizophrenia and autism but were generally similar across heterogenous diagnoses and items. Factor analyses showed that the different behaviors associated with a particular diagnosis were rated more uniformly when they were accompanied by a diagnostic label than when they were not.

Keywords

Mental illness, Stigma, Labeling, Case vignette, DSM-5

Introduction

Being afflicted with a mental illness remains a highly stigmatized condition across different cultures [1,2]. In a highly influential overview on the topic published in 2005, Rüsch and colleagues [3] noted, among other things, what mental illness stigma typically encompasses: frequent prejudices include overestimating the prevalence of violent behavior among people with a mental illness [4] or the belief that those with a mental illness will usually not be able to overcome it [5]. As a consequence, most people with a mental illness report experiencing some form of discrimination [6,7].

Accordingly, they are often cautious about when and to whom to disclose their diagnosis [8], especially because such a disclosure cannot easily be backtracked fully [9]. Such disclosure can result in more experiences of discrimination [10], but evidence is mixed and suggests that disclosure can also have positive consequences such as increased social support [11,12].

A prominent hypothesis in the literature on mental illness stigma proposes that part of the problem in this regard is the practice of labeling mental illnesses with diagnostic terms. Conceptualizing people with a mental illness as an out-group is seen as a central aspect of stigmatization [3]. Categorical diagnostic labels could facilitate such thinking. There is some evidence that thinking of mental illness as a continuum rather than a categorical distinction is associated with less stigma [13], supporting the idea that labels might do more harm than good as they may run counter to such a continuum model.

This argument touches on the more general idea known as the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, first formulated in 1929 [14], according to which language shapes human perception rather than merely being a vehicle for communicating said perception. Under such a framework, it is logical to assume that the language used to talk about marginalized groups matters because it helps to enforce or alleviate the stereotypes that form the basis for stigmatization.

In this vein, Rüsch et al. [3] argued that “language can be a powerful source and sign of stigmatization” (p. 530), pointing out a stark difference between describing physical and mental ailments: it is common to describe a person with schizophrenia as “schizophrenic”, but the equivalent of calling a cancer patient “cancerous” would be highly unusual and inappropriate. Most self-help groups and other advocates for people with mental illnesses accordingly recommend so-called person-first language (such as “a person with schizophrenia”). However, evidence is mixed on whether using person-first language actually reduces stigma, with some studies finding no effect [15], and there are also some authors who see it as misguided [16]. A large-scale study in 2021 [17] found that using different terms for mental illness – such as the strong word “disorder” - had unexpectedly small consequences for participants' attitudes. These results cast doubt on the general importance of word choice. Given these results, labeling effects should not be assumed to be true in the absence of solid empirical evidence, and currently, the effects of using diagnostic labels are still not entirely clear.

The idea that labeling mental illnesses with diagnostic terms aggravates stigmatization was most notably introduced in 1966 by Scheff [18], who went so far as to suggest that diagnostic labels are the core reason why symptoms of mental illnesses are even perceived negatively as disorders rather than fully acceptable deviations from a social norm. Over time, a more moderate view became the consensus: although Scheff's approach was deemed too radical, studies in the following decades did nevertheless show that labeling effects are likely real and impactful [19]. As a more recent illustrative example, Altmann and colleagues [20] showed that using a label when describing relatively mild, marginal cases of mental illness increases perceptions of those symptoms as more stable and less controllable compared to when no label is used. These developments were synthesized into a “modified labeling approach” by Link and colleagues in 1987 [21], which states that although “labeling does not directly produce mental disorder” (p. 400), it nevertheless shapes how especially people with a mental illness view themselves, i.e., labels can lead to self-stigma. The assumption that labels aggravate stigma, either towards oneself or others, has now been part of the mental illness stigma literature for decades and “has almost reached the status of a cultural truism” [22 p 461]. At the same time, empirical evidence is still inconclusive on the extent and nature of labeling effects. In the only broad meta-analysis to date, O'Connor and colleagues [23] reviewed the existing literature and identified 22 studies matching their inclusion criteria. Results differed notably by diagnosis, leading the authors to conclude that “labeling effects cannot meaningfully be discussed in general 'catch-all' terms” [p 7]. Two different overviews are worth mentioning: Sims and colleagues [24] summarized the various psychosocial consequences of receiving a medical diagnosis, including a psychiatric label. However, this review focused on qualitative studies, not on experimental tests of differences between the presence or absence of a label. Despite this, it is noteworthy that results under this qualitative framework are mixed as well. In addition, Franz and colleagues [25] reviewed experimental studies focused specifically on the school context and found that mentioning a diagnosis such as, for example, ADHD was often associated with worse evaluations by teachers. There is therefore better evidence for labeling effects in this particular context than for mental illness labels in general. However, this meta-analysis has similar issues as the one by O'Connor and colleagues: most studies were vignette-based, and results varied considerably by diagnosis.

One reason for these diverse findings is the heterogeneity in approaches. There are countless possible moderators in mental illness stigma research in general – results may differ depending on, among others, which diagnoses, respondents, outcome variables, or culture researchers focus on. Besides these general issues, labeling effects have been investigated using different study designs, with different strengths and drawbacks. For example, studying inferred labels needs to be distinguished from causal effects of assigned labels. A 2003 study [26] that became a frequently cited source of the importance of labeling effects presented participants with unlabeled case vignettes and compared their perception of the person depending on which diagnosis, if any, the participants ascribed to them. While informative, this approach, as well as more recent similar studies [27] does not represent experimental evidence for labeling effects, as participants are not randomly allocated to labeling conditions but introduce the labels themselves (“inferred labels”), possibly leading to confounding effects with previous knowledge about mental illness.

While the literature on labeling effects is generally diverse, most studies do not differ in employing case vignettes to study them. We argue that there is a need for additional and different approaches, in particular because the ecological validity of case vignettes is unclear. The current study was therefore conducted with the aim of testing labeling effects in a more specific context.

A vignette necessarily presents a general overview of a person's symptoms, presenting them in a summarized way that might not reflect the way one gets to know a person in real life. In their review, O'Connor and colleagues [23, p 8] note that using them “comes at the cost of ecological validity”. In everyday interactions, contact with the symptoms of mental illness might often happen one at a time. Meeting a person with ADHD, for example, might entail being confronted with one particular behavior that stands out negatively, i. e., being unpunctual for a meeting. A labeling effect might then change one's reaction to this particular behavior if one knows, or does not know, of this person's diagnosis. The label may amplify an attitude of not wanting to interact with “this kind” of person, but it also appears plausible that it might induce more benevolent reactions by making the behavior understandable. Case vignettes operate on a broader level, inducing a more general picture of a person. They also typically introduce their subject as a person who has mental health issues, is visiting a psychiatrist etc. Even if a vignette does not make this explicit, it is typically obvious to the reader that the vignette is describing a person with a general mental health problem. On the other hand, encountering a single, specific symptom of mental illness – such as unpunctuality in ADHD – might not evoke such associations at all, with the consequence that the behavior is judged under a different framing than when it is part of a case vignette.

Martinez et al. [28] found that introducing a person as having a mental illness induced greater social distance (i.e., higher stigma) compared to mentioning a physical ailment – but the opposite effect occurred when the information was embedded into a story of a person engaging in a number of ambiguous, but somewhat rude behaviors towards others. In other words, as standalone information, a mental illness label provoked negative associations; but in the context of explaining why a person behaves a certain way, the label appeared to be helpful as it put a person's behavior into perspective and made it more understandable, and less blameworthy.

We are not suggesting by any means that case vignettes are not a valuable and informative way to study labeling effects but propose that it is worthwhile to add to those findings an approach that investigates stigmatizing effects at a more concrete level of behavior, especially given the heterogeneity of previous findings as pointed out by O'Connor et al. [23].

Imhoff [22] similarly highlighted the need for studies that focus on comparing perceptions of concrete behavior while experimentally manipulating the presence or absence of a diagnostic label. Using such an approach to test labeling effects on the perception of symptoms of schizophrenia in a large sample, Imhoff [22] then showed that the presence of a label was indeed associated with slightly more negative perceptions of a person in a case vignette that focused on concrete symptoms. The current study aims to conceptually replicate and further develop this approach by presenting symptoms individually instead of embedding them into the wider context of a case vignette.

The main research question of the current study therefore is whether labeling effects might be specific to introducing individuals with mental illness in a vignette-based format or if they persist in an approach that present specific symptoms individually.

Methods and Materials

Participants were recruited among psychology students at Saarland University, Germany. Besides restricting participation to that group, there were no exclusion criteria for participation. The students received course credit for their participation. All materials were presented online and in German.

The data reported here were collected as part of a more extensive survey on attitudes towards mental health and mental illness. This survey was introduced as dealing with “the topic of mental health” in both groups, with no mentioning of labeling effects or stigma. The current study constituted the first part of that larger survey, i. e., no other materials were shown before the materials presented here to avoid disclosing to the participants that the study investigated stigmatizing attitudes.

Participants were randomly allocated to the “label” and “no label” experimental conditions. Instead of describing clinical symptoms in a case vignette, they were presented as standalone items with no explicit connection to each other and no introduction of a specific person. As detailed in the Methods section, this represented a novel approach to measuring labeling effects, introduced with the goal of investigating whether such effects persist even when specific behavior’s rather than more extensive case vignettes are the focus of external judgments.

Each item described a behavior corresponding to a symptom used in the DSM-5 (American Psychological Association, 2013)1 [29] for diagnosing a certain mental illness. Descriptions in the DSM were the basis for phrasing the items but were not used verbatim to reduce the risk of participants recognizing them as diagnostic criteria even in the no label condition. Instead, the phrasing of the items used colloquial language with as few specific terms from clinical psychology as possible.

Both authors phrased candidate items and narrowed them down in a joint process which was guided by several criteria. Symptoms should ideally be specific to one particular diagnosis to ensure that the associations it evoked in the no label condition were similarly narrow to those in the label condition. In other words, we aimed to avoid a situation where participants in the no label condition could react to a symptom in multiple different ways depending on which particular diagnosis it evoked for them. This was inherently not perfectly feasible: even if a symptom is an official criterion only for one particular diagnosis, associations with other disorders are inevitable due to frequent comorbidity. In the DSM-5, 37% of symptoms appear more than once, including 85% of symptoms associated with depressive disorders [30].

Another goal in item construction was to select behaviors that we assumed most people to be familiar with in a milder form. As we hypothesized labeling effects to be particularly relevant in those cases where an afflicted person's symptoms are not strikingly different from “normal” behavior, but rather represent the extreme ends of a continuum, we focused on symptoms suitable to that notion. For example, in anorexia nervosa, focusing on one's body weight and trying to reduce it was deemed a more fitting symptom for our study than, for example, purging behaviors. Such a more extreme symptom is less nuanced, presumably less relatable for a person not afflicted with the disorder (in addition to occurring only in some cases of anorexia nervosa) and is more likely to evoke an association like “eating disorder” in any case, meaning that there might not be a true “no label” condition for such “extreme” symptoms. This also helped making these items as similar as possible to the pseudo-items (see below). Lastly, we aimed to avoid symptoms that can manifest themselves in opposite directions in the same disorder (i. e., reduced or heightened need for sleep in depression, very low or very high reactivity to sensory input in autism spectrum disorders).

Items in the final survey included symptoms of major depression (6 symptoms), social anxiety (4), schizophrenia (3), anorexia nervosa (3), and autism spectrum disorders (3). These are well-known diagnoses that cover a range of diagnoses from relatively low to relatively high levels of stigma [31]. For example, one of the items pertaining to autism spectrum disorders was “Someone feels uncomfortable with changes in their everyday life that require them to change their usual routine”, reflecting in more colloquial language the diagnostic criterion B2 for autism spectrum disorders in the DSM [29]. The different number of items per diagnosis reflects the fact that creating non-redundant items that fulfilled the aforementioned construction principles was more feasible for some diagnoses than for others.

In addition to the items that reflected actual DSM-5 symptoms, we also added a pseudo-item for each diagnosis (two for major depression). These were constructed with the aim of describing behaviors that resemble actual symptoms of the relevant disorder, but are not listed among the official criteria, presumably because they are too common and universal to be selective. For example, the pseudo-item for autism spectrum disorders was “Someone constantly interrupts others and does not seem to listen properly”, as this behavior is close to the difficulties in social reciprocity relevant for diagnosing autism spectrum disorders, but is frequently seen in people without such a disorder as well and does not constitute an explicit diagnostic criterion in the DSM-5. If a diagnostic labeling effect exists and leads to “normal” behavior acquiring a pathological connotation, these pseudo-items should also be perceived differently when presented alongside a label. An even more fundamental effect of such “pseudo-labels” was reported in an earlier vignette-based study: Matsunaga and Kitamura [32] found negative labeling effects even when case vignettes describing major depression were mislabeled as schizophrenia, and vice versa. We refrained from actually mislabeling symptoms with an entirely different diagnosis because we presumed that a substantial proportion of the psychology students who made up our sample would likely recognize these labels as inaccurate.

A full list of the items can be found in the appendix. The order in which the items were presented was fully randomized for each participant.

Participants were instructed to rate the behavior described in each item on a number of semantic differential scales. In the labeling condition, the instruction emphasized that these behaviors were “derived from official criteria in diagnosing mental illnesses, although not verbatim”. In the “no label” condition, no such background information on the items was given. Participants were instructed to answer as spontaneously as possible and reminded that their answers were anonymous.

A sliding scale, ranging from 0 to 100, was used in order to encourage making an effort to rate each item individually rather than repeatedly choosing a middle ground, as this was deemed a likely risk in a repetitive survey on a topic with presumed social desirability in a sample that participated for course credit. If participants skipped an item by leaving the slider in the middle, they were asked to go back and rate the item before they could proceed further in the study.

The semantic differentials on which every behavior was rated were as follows: not normal – normal; self-inflicted (“selbstverschuldet”) – not self-inflicted; rare – frequent; untreatable – treatable; affects me (“betrifft mich selbst”) – does not affect me; unacceptable – acceptable; person is in need of help – person is independent (“selbstständig” - capable of acting on their own). The instructions further clarified the intended meaning of these categories as follows. A behavior was to be rated as “self-inflicted” if it was deemed to be the person's own fault, rather than the result of circumstances beyond their control. “Treatable” referred to the viability of successful therapeutic measures. “Unacceptable” behaviors were meant to be those that a person would not tolerate in their personal environment. “Affects me” referred to whether the participants sometimes felt or behaved in this way as well. Whether the person was “in need of help” was to be judged by how much the behavior made an autonomous, independent life difficult. “Rare – frequent” as well as “normal – not normal” were deemed self-explanatory.

These categories were partly chosen to reflect typical contents of mental illness stigma [3]: personal guilt (“self-inflicted”), social distance (“acceptable”, “normal”, “affects me”), and a tendency to patronize people with mental illness as helpless (“in need of help”). “Not treatable – treatable” was included to examine whether a possible labeling effect leads to a perception of symptoms as more chronic and unchangeable. Additionally, the categories of “self-inflicted”, “rare” and “(not) treatable” were chosen in part based on Feldman and Crandall's findings [31] that these judgments are typical for highly stigmatized mental illnesses. The stereotype of mentally ill people being dangerous, which is central for stigmatization as well according to Feldman and Crandall’s findings [31], was not included because most of the symptoms included could not reasonably be perceived as threatening or dangerous to others.

The use of only these seven rating categories rather than longer scales with established psychometric properties was a necessary consequence of studying labeling effects at the item level – i. e., requiring participants to complete an established scale to measure social distance on every single item was not feasible.

In the label condition, the corresponding label was named in parentheses after each item (including the pseudo-items), as well as the ICD-10 code2 to emphasize the diagnostic nature of the labels. The instruction further clarified that these behaviors represented symptoms used to diagnose mental disorders. The no label condition did not mention mental illness or diagnostic systems. At the end of the questionnaire, participants in the label condition were debriefed to clarify that the pseudo-items did not actually represent diagnostic criteria.

A total of 88 students enrolled in psychology at Saarland University participated in the study. By coincidence, the random allocation to the two labeling conditions resulted in two equally sized groups of 44 participants each. Of those, 74 (84%) were female, with one participant identifying as diverse and the rest as male. Participants were between 18 and 30 years old (mean=21.7, SD=2.8). On average, they had been studying psychology for 3.4 semesters (one and a half years). The two randomly allocated labeling groups did not differ significantly in any of these variables.

Out of the 88 participants, 34 said they had at any point been diagnosed with some form of depression, 10 said so for anorexia, 7 for social anxiety, and one person each said so for schizophrenia and autism spectrum disorders. Overall, 39 out of 88 participants (44%) reported one or more of these diagnoses (partial overlap explains why the numbers do not add up to more than 39). These proportions, especially for depression, are somewhat higher than typical prevalences among the general population in Europe [33-35].

1 Note that data collection in this study took place in 2022, before the publication of the latest text revision of the DSM-5, which was published in September 2022 of that year.

2 Although the DSM was used to generate the items, participants in this German study were assumed to be more familiar with the ICD-10 codes.

Results

Descriptive statistics and intercorrelations between the rating scales, averaged across the 24 symptoms, are presented in Table 1.

|

rating |

M |

SD |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

not normal - normal |

38.53 |

12.04 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

self-inflicted – not self-inflicted |

60.68 |

16.77 |

-.20 [-.39, .01] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

rare - frequent |

54.27 |

12.50 |

.39** [.20, .56] |

-.06 [-.27, .15] |

|

|

|

|

|

not treatable - treatable |

74.43 |

11.44 |

-.14 [-.34, .08] |

.11 [-.10, .31] |

.16 [-.05, .36] |

|

|

|

|

affects me – does not affect me |

31.69 |

14.23 |

.44** [.26, .60] |

-.19 [-.38, .02] |

.34** [.14, .51] |

-.19 [-.39, .02] |

|

|

|

not acceptable - acceptable |

62.01 |

18.29 |

.12 [-.09, .32] |

.39** [.20, .56] |

.35** [.16, .52] |

.31** [.11, .49] |

.01 [-.20, .22] |

|

|

person is in need of help – person is independent |

41.56 |

15.44 |

.35** [.15, .52] |

-.06 [-.26, .15] |

.27* [.07, .46] |

-.15 [-.35, .06] |

.28** [.07, .46] |

.24* [.03, .43] |

|

Note. Ratings can range from 0 – 100. M: Mean; SD: Standard Deviation; 95% confidence intervals given in brackets. *: p<.05; **: p<.01. |

||||||||

Reliability coefficients (Cronbach's Alpha) were computed for each of the rating categories for all 24 items, i e., across diagnoses and including the pseudo-items. Values ranged from 0.88 for “affects me – does not affect me” to 0.96 for “not acceptable – acceptable”, showing that respondents' ratings of behaviors were relatively stable across these heterogenous behaviors and even diagnoses. In other words, interindividual rating tendencies that lead participants to generally rate most behaviors as similarly “acceptable” etc. were much more prominent than intraindividual variance in ratings depending on the specific items or diagnoses.

Table 2 presents fit statistics from confirmatory factor analyses testing how well a model that subsumed the individual items under latent factors reflecting the five diagnoses used in the study fit the rating data. These were conducted separately for each rating category as well as for the two labeling conditions. Results show that the fit statistics generally fall short of conventional thresholds for a good model fit. This may partially result from the sample size, which was far below what is recommended for factor analysis. However, the goal of the current analysis was not to rigorously test the factor structure of the items, but to compare the model fit between the labeling conditions. In this regard, Table 2 shows that across the different rating categories, the fit statistics mostly indicate a better fit in the “label” than in the “no label” condition. In other words, the presence of a diagnostic label elicited higher intercorrelations among symptoms (including the pseudo-items) that shared the same label compared to when each symptom was presented without any label.

|

rating |

labeling condition |

CFI |

RMSEA |

BIC |

|

not normal - normal |

label |

0.644 |

0.134 |

9170.649 |

|

no label |

0.536 |

0.138 |

9384.570 |

|

|

self-inflicted – not self-inflicted |

label |

0.759 |

0.145 |

9018.991 |

|

no label |

0.607 |

0.147 |

8976.425 |

|

|

rare - frequent |

label |

0.697 |

0.119 |

8713.773 |

|

no label |

0.697 |

0.131 |

8254.900 |

|

|

not treatable - treatable |

label |

0.658 |

0.156 |

8277.304 |

|

no label |

0.551 |

0.156 |

8763.682 |

|

|

affects me – does not affect me |

label |

0.709 |

0.117 |

9271.786 |

|

no label |

0.612 |

0.117 |

9779.039 |

|

|

not acceptable - acceptable |

label |

0.776 |

0.137 |

9213.555 |

|

no label |

0.731 |

0.158 |

8880.057 |

|

|

person is in need of help – person is independent |

label |

0.749 |

0.125 |

8951.910 |

|

no label |

0.727 |

0.115 |

9254.761 |

|

|

Note. CFI: Comparative Fit Index; RMSEA: Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation; BIC: Bayesian Information Criterion. Better fit indicated by higher values in CFI and lower values in RMSEA and BIC. |

||||

To analyze which variables influenced the perception of individual behaviors, we conducted mixed linear regressions predicting each of the seven different ratings separately. The diagnosis an item pertained to, as well as the specific item itself, were modeled as random effects in order to test how much of the heterogeneity in the data could be attributed to the particular behaviors that were chosen from the wider range of possible symptoms and psychiatric diagnoses. The labeling condition (label vs. no label), the nature of the item (true symptom or pseudo-item) and a variable encoding whether or not the rater reported being afflicted with the diagnosis in question themselves, either currently or in the past, were modelled as fixed effects, along with the interactions between the labeling condition and either of the other two fixed effects. These interactions tested the possibility that the extent of labeling effects may depend on the nature of the item or the rater's own affliction with the diagnosis in question.

Results of the regression models for each of the seven outcome categories are presented in (Tables 3 (fixed effects) and 4 (random effects)). Following a standard correction for multiple testing (Bonferroni correction), only p values below 0.05 / 49 ≈ 0.001 should be interpreted (as seven different regressions with seven parameters each were run). Under this threshold, the experimental condition of labeled vs unlabeled symptoms was a significant predictor of four of the seven rating categories. In particular, participants in the label condition were more likely than those in the no label condition to rate symptoms as less common, less typical of themselves, less self-inflicted / blameworthy and more indicative of a person in need of external assistance. The rating differences of how normal and acceptable behaviors were judged to be did not remain significant after taking into account multiple testing. Ratings of treatability did not differ between labeling conditions under either threshold. Several of the rating averages were significantly higher among older participants, and two rating categories differed by sex. Additionally, participants who had at any point been diagnosed with the mental illness relevant to an item on average rated the behavior in question as more normal and as more typical for themselves. No other main or interaction effects reached significance when correcting for multiple testing. The status of an item as a genuine or pseudo-symptom (pseudo-items) was in some cases associated with substantial point estimates, but large standard errors due to the relatively small number of pseudo-items meant that these possible effects were not robust enough to reach statistical significance.

|

Rating |

Effect |

Estimate |

SE |

95% CI |

p |

|

|

lower |

upper |

|||||

|

not normal - normal |

Intercept |

17.448 |

8.132 |

0.812 |

33.968 |

|

|

age |

0.855 |

0.173 |

0.517 |

1.193 |

<0.001 |

|

|

Sex a |

2190 |

1.171 |

-0.102 |

4.483 |

0.062 |

|

|

labeling condition b |

-3.418 |

1.171 |

-5.710 |

-1.125 |

0.004 |

|

|

pseudo-item c |

12.249 |

5.796 |

0.624 |

23.873 |

0.048 |

|

|

own diagnosis d |

-8.160 |

1.892 |

-11.859 |

-4.452 |

<0.001 |

|

|

labeling condition * pseudo-item |

-2.686 |

2.183 |

-6.960 |

1.589 |

0.219 |

|

|

labeling condition * diagnosis |

6.711 |

2.557 |

1.705 |

11.719 |

0.009 |

|

|

self-inflicted – not self-inflicted |

Intercept |

31.210 |

5.868 |

19.855 |

42.614 |

|

|

age |

1.176 |

0.190 |

0.804 |

1.574 |

<0.001 |

|

|

sexa |

1.900 |

1.286 |

-0.618 |

4.418 |

0.140 |

|

|

labeling conditionb |

10.373 |

1.286 |

7.855 |

12.892 |

<0.001 |

|

|

pseudo-itemc |

-10.535 |

3.936 |

-18.395 |

-2.676 |

0.014 |

|

|

own diagnosisd |

3.116 |

2.077 |

-0.975 |

7.161 |

0.134 |

|

|

labeling condition* pseudo-item |

2.664 |

2.401 |

-2.036 |

7.365 |

0.267 |

|

|

labeling condition* diagnosis |

1.908 |

2.808 |

-3.593 |

7.404 |

0.500 |

|

|

rare - frequent |

Intercept |

55.3849 |

8.147 |

38.671 |

72.083 |

|

|

age |

0.1944 |

1.212 |

-0.129 |

0.518 |

0.005 |

|

|

sex a |

-3.161 |

0.615 |

-5.357 |

-0.965 |

0.239 |

|

|

labeling condition b |

-6.7355 |

1.125 |

-8.939 |

-4.533 |

<0.001 |

|

|

pseudo-item c |

8.414 |

3.503 |

1.420 |

15.408 |

0.025 |

|

|

own diagnosis d |

-0.397 |

1.857 |

-4.026 |

3.246 |

0.831 |

|

|

labeling condition * pseudo-item |

-2.566 |

2.010 |

-6.677 |

1.545 |

0.222 |

|

|

labeling condition * diagnosis |

1.475 |

2.481 |

-3.381 |

6.333 |

0.552 |

|

|

not treatable - treatable |

Intercept |

82.363 |

4.204 |

73.375 |

90.343 |

|

|

age |

-0.203 |

1.009 |

-0.494 |

0.088 |

0.172 |

|

|

sex a |

-2.272 |

0.149 |

-4.246 |

-0.298 |

0.024 |

|

|

labeling condition b |

1.025 |

1.009 |

-0.951 |

2.999 |

0.310 |

|

|

pseudo-item c |

-2.646 |

1.331 |

-5.242 |

-0.030 |

0.048 |

|

|

own diagnosis d |

-4.583 |

1.628 |

-7.749 |

-1.379 |

0.005 |

|

|

labeling condition * pseudo-item |

1.040 |

1.883 |

-2.646 |

4.727 |

0.581 |

|

|

labeling condition * diagnosis |

7.007 |

2.203 |

2.699 |

11.323 |

0.001 |

|

|

affects me – does not affect me |

Intercept |

53.394 |

7.785 |

37.942 |

68.832 |

|

|

age |

0.582 |

1.411 |

-0.989 |

-0.174 |

0.005 |

|

|

sex a |

-6.605 |

0.208 |

-9.368 |

-3.842 |

<0.001 |

|

|

labeling condition b |

8.224 |

1.411 |

-10.986 |

-5.461 |

<0.001 |

|

|

pseudo-item c |

2.706 |

5.457 |

-8.226 |

13.638 |

0.625 |

|

|

own diagnosis d |

14.095 |

2.279 |

9.641 |

18.565 |

<0.001 |

|

|

labeling condition * pseudo-item |

-0.053 |

2.632 |

-5.207 |

5.102 |

0.984 |

|

|

labeling condition * diagnosis |

6.765 |

3.086 |

0.726 |

12.811 |

0.028 |

|

|

not acceptable - acceptable |

Intercept |

50.715 |

5.460 |

40.127 |

61.303 |

|

|

age |

0.596 |

0.202 |

0.199 |

0.992 |

0.003 |

|

|

sex a |

-0.072 |

1.374 |

-2.763 |

2.618 |

0.958 |

|

|

labeling condition b |

2.923 |

1.374 |

0.232 |

5.614 |

0.034 |

|

|

pseudo-item c |

-10.179 |

5.769 |

-21.428 |

1.071 |

0.090 |

|

|

own diagnosis d |

-0.295 |

2.220 |

-4.61 |

4.049 |

0.894 |

|

|

labeling condition * pseudo-item |

2.298 |

2.562 |

-2.719 |

7.315 |

0.370 |

|

|

labeling condition * diagnosis |

3.332 |

3.005 |

-2.549 |

9.217 |

0.268 |

|

|

person is in need of help – person is independent |

Intercept |

30.894 |

|

15.838 |

45.943 |

|

|

age |

0.815 |

0.192 |

0.438 |

1.191 |

<0.001 |

|

|

sex a |

-5.346 |

1.305 |

-7.901 |

-2.789 |

<0.001 |

|

|

labeling condition b |

-5.988 |

1.306 |

-8.546 |

-3.431 |

<0.001 |

|

|

pseudo-item c |

14.546 |

4.148 |

6.258 |

22.835 |

0.002 |

|

|

own diagnosis d |

-1.913 |

2.114 |

-6.050 |

2.230 |

0.366 |

|

|

labeling condition * pseudo-item |

-3.816 |

2.434 |

-8.582 |

0.950 |

0.117 |

|

|

labeling condition * diagnosis |

1.984 |

2.854 |

-3.604 |

7.574 |

0.487 |

|

|

Note. Ratings ranged from 0 – 100. a1 = female, 2 = male. b0 = no diagnostic label mentioned, 1 = diagnostic label mentioned. c0 = genuine diagnostic symptom, 1 = pseudo-symptom (see Methods section). d1 = participant reported having at any point been diagnosed with the mental illness relevant for the specific item, 0 = participant did not report such a diagnosis. SE: Standard Error; CI: Confidence Interval. Effects that remain significant at p<0.05 after accounting for multiple testing are printed in bold. |

||||||

In line with the high reliability coefficients presented earlier, the random effects included to model the heterogeneity introduced by the diverse diagnoses and symptoms included in the survey explained only modest amounts of variance. These results are presented in Table 4. The proportion of variance explained by both factors together ranged from 7.5% for ratings of treatability to 42.5% for ratings of normality of symptoms. Diagnoses, rather than specific symptoms, had a larger effect on average. Notably, ratings of acceptableness did not differ by diagnosis even though some of the diagnoses used in the current study are typically associated with higher stigmatization than others [31].

|

Rating |

Effect |

Proportion of variance explained |

|

not normal - normal |

diagnosisa |

25.4% |

|

specific item / symptom |

17.1% |

|

|

self-inflicted – not self-inflicted |

diagnosis a |

8.5% |

|

specific item / symptom |

8.3% |

|

|

rare - frequent |

diagnosis a |

33.9% |

|

specific item / symptom |

6.3% |

|

|

not treatable - treatable |

diagnosis a |

7.5% |

|

specific item / symptom |

0.0% |

|

|

affects me – does not affect me |

diagnosis a |

15.8% |

|

specific item / symptom |

12.4% |

|

|

not acceptable – acceptable |

diagnosis a |

0.0% |

|

specific item / symptom |

17.2% |

|

|

person is in need of help – person is independent |

diagnosis a |

15.8% |

|

specific item / symptom |

12.4% |

|

|

Note. aDiagnosis associated with the behavior described in the item, including pseudo-symptoms (pseudo-items). Remaining variance is residual variance. |

||

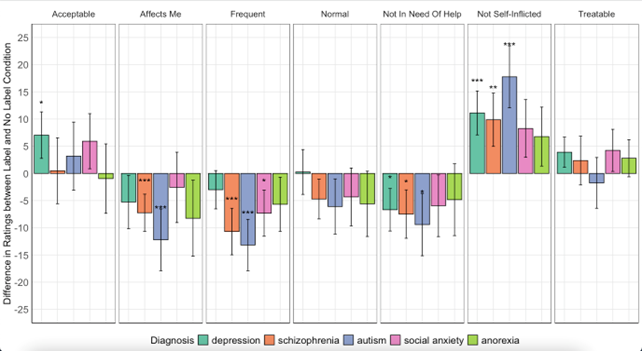

Figure 1. Labeling Effects by Diagnosis and Rating Category. Note. Mean differences in absolute ratings between the label and no label conditions across different diagnoses. Since ratings can range from 0-100, differences can accordingly range from -100 to +100. Positive values indicate higher ratings of labeled versus unlabeled symptoms in the direction of the attribute specified at the top. Error bars show 95% confidence intervals. Asterisks denote p-values after applying Bonferroni corrections for multiple testing, i.e.: *p<.05 / 35, **p<.01 / 35, ***p<.001 / 35.

Figure 1 illustrates the labelling effects grouped by the diagnosis the symptom pertained to (or was claimed to pertain to in the study, in case of the pseudo-items) for each of the rating categories. Modeling the individual diagnoses as random effects implied that the regression models did not test specific hypotheses about which diagnoses and items influenced ratings in which direction, or whether the labeling effect (as opposed to overall mean levels of ratings) differed between them. The alpha level for significant differences shown in the graphs was corrected by a factor of 35 in order to account for the testing of five effects across seven rating scales. In general, numerical differences between the label and no label conditions almost uniformly point in the same direction for each rating, regardless of diagnosis. However, significant differences appear to be driven by ratings of symptoms of schizophrenia and autism more so than other diagnoses.

Discussion

The current study presents a novel approach towards testing labeling effects on the perception of people with mental illness. Participants rated specific behaviors typical for five different diagnoses, as well as pseudo-items that did not reflect genuine diagnostic criteria, on seven dimensions. Results show that mentioning a diagnostic label versus omitting it was associated with small, but significant rating differences for some, but not all of the rating categories. Labeled behaviors were perceived as less common, less typical of the raters themselves, less self-inflicted (not the person's own fault) and more indicative of a person being dependent on external help. In contrast, numerical differences in how normal, acceptable and treatable the symptoms were perceived to be with or without a label did not remain significant after controlling for multiple testing.

Notably, these labeling effects were mostly independent of other boundary conditions. Firstly, they were present across both “true” symptoms and pseudo-items, which described similar but non-pathological behavior. This lack of an interaction between the veracity of a symptom and the presence or absence of a label may suggest that the perception of behaviors that are not actually indicative of a mental illness is just as affected by (mis)labeling them as is the case for actual symptoms, an effect similar to what Matsunaga et al. [32] had found in a study using case vignettes. Secondly, the main effect of the labeling condition also did not significantly (after accounting for multiple testing) interact with the rater's own present or past affliction with the diagnosis in question. While self-stigma is an entirely different and complex field of study within the mental illness stigma literature [36], this uniform non-result across all seven rating categories suggests that labeling impacts perceptions similarly whether or not individuals identify with the diagnosis personally. Further research in this regard is needed, especially because for four of the five diagnoses used in the current study, only a small minority of the sample reported having had this illness at any point, and because possible small, but robust interaction effects would require a larger sample size to be detected reliably.

The hypothesis that the use of diagnostic labels may be aggravating or at least facilitating mental illness stigma has a long history in practice and research, but there is still no clear consensus on how and when such labels influence the way people with mental illnesses are perceived and judged. The so far very mixed findings [23] may partially stem from different contexts, paradigms and wordings used in any given individual study, as there is no “gold standard” approach to measuring such effects. The goal of introducing yet another method in the current study was not to claim that this approach should replace the vignette paradigm, but to test whether labeling effects would still be measurable with as few context clues as possible. Results show that for the most part, they do still have an effect.

In line with the heterogeneity of previous findings, the labeling effects found in the current study vary by category. Ratings of how acceptable, normal or treatable behaviors are did not robustly differ between labeling conditions in the current study. Out of the four robust labeling effects that were found, three imply more negative perceptions of labeled symptoms, but the fourth one is arguably positive - symptoms were on average perceived to be less of the person's own fault. It is noteworthy that other research suggests that this does not necessarily translate to lower stigma: focusing (solely) on biological explanation mechanisms of mental illness in educating the public has repeatedly been found to backfire by leading to more stigmatization despite also reducing impressions of blameworthiness [37,38]. This may be because attributing mental illness to root causes outside a person's control not only reduces blame, but also the perceived chances of recovery [37]. However, such a pattern was not present in the current study as ratings of blameworthiness and of treatability – a similar concept to chances of recovery – were not significantly correlated.

Further research is needed to elucidate how labels impact perceptions of mental illness, and under which conditions specifically. For example, these processes might depend heavily on specific characteristics of the rater. Most studies on labeling effects do not control whether the raters were themselves afflicted by a given diagnosis (see O’Connor et al. [23], which makes the inclusion of this factor in the current study valuable. However, numerous other factors that shape the impact of diagnostic labels are possible and worth investigating. Previous knowledge about the topic, previous contact with people with a certain diagnosis [39], as well as general personality characteristics might influence reactions to labeled and unlabeled behavior.

In a secondary finding, we found that when a label was present, items belonging to the same diagnosis received more consistent ratings than unlabeled items, as indicated by improved model fit in confirmatory factor analyses. This finding supports the idea that mentioning a label leads to more generalized, stereotypical perceptions: with the label present, participants rate the behaviors with the same label more uniformly. In other words, participants apparently used their general opinion about, for example, schizophrenia to guide their ratings of specific behaviors, either consciously or unconsciously.

The current findings clearly cannot be taken to mean that using diagnostic labels in psychology is always harmful and should be abolished, or that it is ill-advised for people with mental illnesses to open up about their condition to others. Instead, studies such as the current one can attempt to clarify what consequences the use of a diagnostic label may have under which circumstances – including positive consequences. The current findings might suggest, for instance, that labeling effects could be helpful in situations in which an individual wants their condition to be perceived as unusual. For example, consciously using the label of “social anxiety disorder” might serve to emphasize that a person's fear of an upcoming social situation should be taken seriously rather than being mistaken for everyday shyness. In other situations, such as a job interview, consequences such as being perceived as unusual, less relatable and in need of external help may be clearly unwelcome and using a label may thus do more harm than good.

Limitations

The scope of the current study is limited by several factors: first of all, the results reported here are specific to the sample of mostly female undergraduate psychology students (which was further narrowed down by self-selection bias, as participation in the study was not mandatory for course credit). All of them were at most 30 years old as well, even though the study was not explicitly age-restricted. It stands to reason that this group does not represent the general population regarding factors such as overall stigma towards mental illness or prior familiarity with the topic.

Previous studies do show that stigmatizing attitudes and behavior are prevalent even among psychology students or even professionals in psychology and medicine [40-43], especially students at the bachelor rather than master level, as in the current sample [44]. Some studies even find no difference at all in stigmatizing attitudes between the general population and mental health professionals such as psychiatrists [45-46]. Accordingly, it is not unusual to investigate labeling effects among psychology students: this was the case for five of the 22 studies included in the meta-analysis [23]. In addition, ratings in the current study were mostly not obviously stigmatizing or degrading, and participants' ratings were generally well distributed (i.e., not subject to floor or ceiling effects, as might be the case in this group when measuring agreement with overtly stigmatizing statements). The fact that the mere presence of a diagnostic label still reframed participants’ perceptions of behaviors even among a group that likely thinks of mental illness in a less categorical way than the general population arguably demonstrates the fundamental nature of labeling effects. When and how diagnostic labels should be used to communicate about mental illness is a relevant question not only in everyday interactions, but also in therapeutic settings such as psychotherapy or psychiatry, which is in fact one of the most frequent contexts where people with mental illness experience stigmatization [47]. Still, the specific sample in the current study naturally limits the generalizability of the current results, and a replication of the approach presented here in the general population would be desirable.

We did not explore to what extent participants in the “no label” condition may still internally have ascribed a label to the unlabeled behaviors. However, the uniformity of labeling effects, irrespective of the participant's own diagnostic history, suggests that labeling effects are constant across levels of previous knowledge. Further research is necessary to more directly explore this.

The items and diagnoses used in the current study were not previously established materials and represent a necessarily subjective and somewhat arbitrary selection among the very diverse and wide field of psychiatric diagnoses. Modeling the heterogeneity introduced by these choices as random effects in the regression models accounts for this “random” selection from a larger possible pool of items. This analysis revealed only modest influences on the variability of the ratings. Similarly, high internal consistencies across items within participants also suggested that the variability in symptoms and diagnoses only had a minor impact on ratings in the current study.

Furthermore, the scope of outcomes in the current study was necessarily limited. Single-item measures such as the ones used here can work reasonably well for simple judgments [48], but they are still suboptimal, and future studies might additionally want to test for other kinds of judgments, such as the person's perceived competence and warmth [49].

Conclusion

The current study presented specific behaviors that exemplified symptoms, or pseudo-symptoms, of five different psychiatric diagnoses to a sample of psychology undergraduates. Results show that when a diagnostic label was mentioned after each of these behaviors, participants rated the behaviors on average as less typical for themselves and less common. The fictitious person showing this behavior was rated as less blameworthy, but also as more dependent on outside help. Ratings of how normal, acceptable or treatable the behaviors are did not differ between labeling conditions.

These results were generally independent of the rater's own affliction with the diagnosis in question as well as whether the behavior represented a genuine diagnostic criterion. The heterogeneity in diagnoses represented in the items as well as specific variance attributable to the individual items themselves only explained small to medium amounts of variance in the ratings. In other words, labeling effects appeared to be mostly uniform across various contexts.

These findings demonstrate that labeling effects persist at the level of specific behaviors and are therefore not simply method artifacts of the standard approach, which is to present a case vignette describing a specific person with a mental illness in a summary fashion. Similar to the findings by Martinez et al. [28], labels partly led to more positive rather than negative ratings in the form of reduced blame or guilt.

While the current results need to be interpreted in the context of the specific sample of psychology students and may differ when replicated among the general population, they do suggest that labeling effects exist across different mental illnesses and that they are not specific to the case vignette approach. Confirmatory factor analyses in the current study offer tentative evidence that this may partly be because the presence of a label leads to more similar ratings within the group of behaviors that are labeled the same, compared to when these behaviors come without a label.

For people with a mental illness, the question of whether and when to disclose their diagnosis often has high-stakes implications: will it backfire and lead to more stigmatizing attitudes and possibly discriminating behavior, or will it improve their quality of life through more acceptance and understanding? In general, the benefits often end up outweighing the risks, but it remains a difficult dilemma [50]. The current study cannot provide conclusive answers to this question. The best approach may depend on the specific context. Research on thinking of mental health as a continuum rather than dichotomous distinctions between “mentally healthy” and “mentally ill” has shown promising results [13]. This is not necessarily a contradiction to findings that show possible beneficial effects of using diagnostic labels, but how these two approaches may best be used in conjunction remains an open question. In any case, it is clear that labeling effects are not yet fully understood, and that further research is warranted.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Frank M. Spinath for providing helpful comments on earlier versions of this manuscript.

Author Contributions Statement

Both authors developed the research question and contributed to designing and implementing the study. Alexander Dings implemented the statistical model and wrote the manuscript.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. In particular, they gave their written consent to the data privacy regulations pertaining to the study and were informed that they could cancel their participation at any point. They were also informed that participation was anonymous.

References

2. Fekih-Romdhane F, Jahrami H, Stambouli M, Alhuwailah A, Helmy M, Shuwiekh HA, et al. Cross-cultural comparison of mental illness stigma and help-seeking attitudes: a multinational population-based study from 16 Arab countries and 10,036 individuals. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2023 Apr;58(4):641-56.

3. Rüsch N, Angermeyer MC, Corrigan PW. Mental illness stigma: Concepts, consequences, and initiatives to reduce stigma. Eur Psychiatry. 2005;20(8):529-39.

4. Almomen ZA, Alqahtani AH, Alafghani LA, Alfaraj AF, Alkhalifah GS, Jalalah NH, et al. Homicide in relation to mental illness: stigma versus reality. Cureus. 2022 Dec;14(12).

5. Seeman N, Tang S, Brown AD, Ing A. World survey of mental illness stigma. J Affect Disord. 2016;190:115-21.

6. Antunes A, Silva M, Azeredo-Lopes S, Cardoso G, Caldas-de-Almeida JM. Perceived stigma and discrimination among persons with mood and anxiety disorders: Results from the WHO World Mental Health Survey Portugal. The European Journal of Psychiatry. 2022 Oct 1;36(4):280-7.

7. Lasalvia A, Zoppei S, Van Bortel T, Bonetto C, Cristofalo D, Wahlbeck K, et al. Global pattern of experienced and anticipated discrimination reported by people with major depressive disorder: a cross-sectional survey. Lancet. 2013;381(9860):55-62.

8. Pahwa R, Fulginiti A, Brekke JS, Rice E. Mental illness disclosure decision making. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2017;87(5):575.

9. Mickelberg AJ, Walker B, Ecker UK, Fay N. Helpful or harmful? The effect of a diagnostic label and its later retraction on person impressions. Acta Psychologica. 2024 Aug 1;248:104420.

10. Pheister M, Peters RM, Wrzosek MI. The impact of mental illness disclosure in applying for residency. Acad Psychiatry. 2020;44:554-61.

11. Dewa CS, Van Weeghel J, Joosen MC, Gronholm PC, Brouwers EP. Workers' decisions to disclose a mental health issue to managers and the consequences. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2021 Mar 26;12:631032.

12. Jones AM. Disclosure of mental illness in the workplace: A literature review. Am J Psychiatr Rehabil. 2011;14(3):212-29.

13. Peter LJ, Schindler S, Sander C, Schmidt S, Muehlan H, McLaren T, et al. Continuum beliefs and mental illness stigma: a systematic review and meta-analysis of correlation and intervention studies. Psychol Med. 2021;51(5):716-26.

14. Sapir E. The status of linguistics as a science. Language. 1929;5(4):207-14.

15. Masland SR, Null KE. Effects of diagnostic label construction and gender on stigma about borderline personality disorder. Stigma and Health. 2022 Feb;7(1):89.

16. Granello DH, Gibbs TA. The power of language and labels: “the mentally ill” versus “people with mental illnesses”. J Couns Dev. 2016;94(1):31-40.

17. Fox AB, Vogt D, Boyd JE, Earnshaw VA, Janio EA, Davis K, et al. Mental illness, problem, disorder, distress: does terminology matter when measuring stigma?. Stigma and Health. 2021 Nov;6(4):419.

18. Scheff T. Being mentally ill: A sociological theory. Chicago: Aldine; 1966.

19. Link BG. Understanding labeling effects in the area of mental disorders: An assessment of the effects of expectations of rejection. Am Sociol Rev. 1987;96–112.

20. Altmann B, Fleischer K, Tse J, Haslam N. Effects of diagnostic labels on perceptions of marginal cases of mental ill-health. PLOS Mental Health. 2024 Aug 28;1(3):e0000096.

21. Link BG, Cullen FT, Struening E, Shrout PE, Dohrenwend BP. A modified labeling theory approach to mental disorders: An empirical assessment. Am Sociol Rev. 1989;400-23.

22. Imhoff R. Zeroing in on the effect of the schizophrenia label on stigmatizing attitudes: a large-scale study. Schizophr Bull. 2016;42(2):456-63.

23. O’Connor C, Brassil M, O’Sullivan S, Seery C, Nearchou F. How does diagnostic labeling affect social responses to people with mental illness? A systematic review of experimental studies using vignette-based designs. J Ment Health. 2022;31(1):115-30.

24. Sims R, Michaleff ZA, Glasziou P, Thomas R. Consequences of a diagnostic label: a systematic scoping review and thematic framework. Frontiers in Public Health. 2021 Dec 22;9:725877.

25. Franz DJ, Richter T, Lenhard W, Marx P, Stein R, Ratz C. The influence of diagnostic labels on the evaluation of students: A multilevel meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review. 2023 Mar;35(1):17.

26. Angermeyer MC, Matschinger H. The stigma of mental illness: effects of labelling on public attitudes towards people with mental disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2003;108(4):304-9.

27. Manago B, Mize TD. What Is the Effect of an Inferred Mental Illness Label on Stigma? Theoretical and Empirical Challenges. Socius. 2024 Sep;10:23780231241274237.

28. Martinez AG, Piff PK, Mendoza-Denton R, Hinshaw SP. The power of a label: Mental illness diagnoses, ascribed humanity, and social rejection. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2011;30(1):1-23.

29. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th edn. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

30. Forbes MK, Neo B, Nezami OM, Fried EI, Faure K, Michelsen B, et al. Elemental psychopathology: Distilling constituent symptoms and patterns of repetition in the diagnostic criteria of the DSM-5. Psychol Med. 2024;54(5):886-94.

31. Feldman DB, Crandall CS. Dimensions of mental illness stigma: What about mental illness causes social rejection? J Soc Clin Psychol. 2007;26(2):137-54.

32. Matsunaga A, Kitamura T. The effects of symptoms, diagnostic labels, and education in psychiatry on the stigmatization towards schizophrenia: a questionnaire survey among a lay population in Japan. Ment Illn. 2016;8(1):16-20.

33. Sacco R, Camilleri N, Eberhardt J, Umla-Runge K, Newbury-Birch D. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the prevalence of mental disorders among children and adolescents in Europe. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2024 Sep;33(9):2877-94.

34. Jacobi F, Höfler M, Siegert J, Mack S, Gerschler A, Scholl L, et al. Twelve-month prevalence, comorbidity and correlates of mental disorders in Germany: The Mental Health Module of the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Adults (DEGS1-MH). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2014;23(3):304-19.

35. Thom J, Bretschneider J, Kraus N, Handerer J, Jacobi F. Versorgungsepidemiologie psychischer Störungen. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2019;62(2):128-39.

36. Dubreucq J, Plasse J, Franck N. Self-stigma in serious mental illness: A systematic review of frequency, correlates, and consequences. Schizophrenia bulletin. 2021 Sep 1;47(5):1261-87.

37. Kvaale EP, Haslam N, Gottdiener WH. The ‘side effects’ of medicalization: A meta-analytic review of how biogenetic explanations affect stigma. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33(6):782-94.

38. Ahuvia IL, Sotomayor I, Kwong K, Lam FW, Mirza A, Schleider JL. Causal beliefs about mental illness: A scoping review. Social Science & Medicine. 2024 Feb 15:116670.

39. Potts LC, Henderson C. Moderation by socioeconomic status of the relationship between familiarity with mental illness and stigma outcomes. SSM-Population Health. 2020 Aug 1;11:100611.

40. Lien YY, Lin HS, Lien YJ, Tsai CH, Wu TT, Li H, et al. Challenging mental illness stigma in healthcare professionals and students: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Psychology & Health. 2021 Jun 14;36(6):669-84.

41. Valery KM, Prouteau A. Schizophrenia stigma in mental health professionals and associated factors: A systematic review. Psychiatry Research. 2020 Aug 1;290:113068.

42. Riffel T, Chen SP. Stigma in healthcare? Exploring the knowledge, attitudes, and behavioural responses of healthcare professionals and students toward individuals with mental illnesses. Psychiatric Quarterly. 2020 Dec;91(4):1103-19.

43. Jauch M, Occhipinti S, O’Donovan A. The stigmatization of mental illness by mental health professionals: Scoping review and bibliometric analysis. PLoS One. 2023;18(1):e0280739.

44. Pranckeviciene A, Zardeckaite-Matulaitiene K, Marksaityte R, Endriulaitiene A, Tillman DR, Hof DD. Social distance in Lithuanian psychology and social work students and professionals. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2018;53(8):849-57.

45. Reavley NJ, Mackinnon AJ, Morgan AJ, Jorm AF. Stigmatising attitudes towards people with mental disorders: a comparison of Australian health professionals with the general community. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2014;48(5):433-41.

46. Nordt C, Rössler W, Lauber C. Attitudes towards people with mental illness in Europe. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;208(3):243-50.

47. Schulze B. Stigma and mental health professionals: A review of the evidence on an intricate relationship. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2007;19(2):137-55.

48. Allen MS, Iliescu D, Greiff S. Single item measures in psychological science: A call to action [Editorial]. Eur J Psychol Assess. 2022;38(1):1-5.

49. Görzig A, Ryan LN. The different faces of mental illness stigma: Systematic variation of stereotypes, prejudice and discrimination by type of illness. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology. 2022 Oct;63(5):545-54.

50. Mayer L, Corrigan PW, Eisheuer D, Oexle N, Rüsch N. Attitudes towards disclosing a mental illness: impact on quality of life and recovery. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2022;57(2):363-74.