Abstract

Background: Traditionally, cytotoxic chemotherapy dominated cancer treatment, but in recent years, immunotherapies, mainly immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), have revolutionized cancer therapy by enhancing T-cell responses. Despite their efficacy, ICIs can induce toxicities affecting various organs, including the nervous system. Although rare, neurological complications of ICIs can be severe, contributing significantly to treatment-related mortality. Atezolizumab, targeting programmed death ligand 1, is approved for various cancers, with a side effect profile akin to other ICIs. While neurological adverse events with atezolizumab are less frequent, serious cases have been documented. Diagnosing these events is challenging due to atypical symptoms and limited experience in managing them. This review aimed to characterize the clinical presentation of atezolizumab-induced neurotoxicity, including neurological symptoms, diagnostic approaches, and treatment outcomes.

Methods: A Medline search conducted on atezolizumab-induced neurotoxicity using PubMed, ScienceDirect, and Google Scholar databases until March 15, 2024.

The search strategy encompassed MeSH terms and free-text words, incorporating terms such as atezolizumab, PD-L1, neurotoxicity, and various neurological adverse events. Inclusion criteria comprised English language publications, all age groups, randomized clinical trials, observational studies, systematic reviews, case reports, and case series.

Results: Of the 56 citations identified, 39 (representing 45 patients’ cases) were included. Atezolizumab-induced neurotoxicity exhibits various clinical presentations, with grades 1-2 neurotoxicities being common and typically nonspecific, while grades 3-4 syndromes are less frequent and more severe. These adverse events were documented across various cancer types, with patients who had a median age of 58 years. Symptoms typically appeared after the first cycle of atezolizumab therapy, with a median onset of two weeks after the last dose. Management typically involved steroid therapy, with a few patients requiring additional interventions such as intravenous immunoglobulin or plasmapheresis. Symptoms usually resolved within a median of 10 days after atezolizumab cessation, with partial or complete recovery in most cases. Fatal outcomes were observed in 10 cases, although causality was not definitively established in all instances.

Conclusions: Atezolizumab-induced neurotoxicity is challenging to recognize due to widely varying symptoms, emphasizing the need for a thorough safety assessment to determine the incidence and patient risk profiles.

Continued research into this adverse event is crucial for understanding patient susceptibility and developing effective management strategies.

Keywords

Immune related adverse events, Central nervous system, Atezolizumab, Immune checkpoint inhibitors, Neurological complications, Encephalitis, Neuropathy, Coma, Seizures

Background

Traditional cytotoxic chemotherapy has historically been the primary approach for treating various malignant tumors. However, in recent years, remarkable advancements in cancer management strategies have emerged with the introduction of immunotherapies, signaling a new era in anti-neoplastic therapy [1]. Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), predominantly composed of programmed cell death protein 1, programmed cell death 1 ligand 1 (PD-L1), and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 monoclonal antibodies, constitute a class of immunotherapy that enhances antitumor immune responses by upregulating T-cell activity [1-3]. While ICIs have demonstrated high response rates in patients with various advanced malignancies, they can also be associated with several toxicities affecting any organ system including the nervous system [4]. Neurotoxicity triggered by ICIs can impact various components of the nervous system, including the central nervous system (CNS), the peripheral nervous system (PNS), and the neuroendocrine system [1]. Although neurological toxicities of ICIs are rare accounting for approximately 2% to 4% of all adverse effects, they can exhibit increased severity compared to other complications and pose life-threatening risks if left undiagnosed or poorly managed [1,2]. Previous research has suggested that neurologic adverse effects have been implicated in nearly half of all deaths associated with ICIs [4]. Atezolizumab, an immune checkpoint inhibitor that selectively binds to PD-L1 [5], is approved for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), small-cell lung cancer (SCLC), advanced triple-negative breast cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and urothelial carcinoma and is currently under study for the treatment of lymphoma, melanoma, gynecological and colorectal malignancies [6,7]. Atezolizumab exhibits a side effect profile comparable to other ICIs, commonly manifesting as fatigue, rash, and gastrointestinal symptoms [8,9].

The incidence of neurological adverse events associated with atezolizumab is relatively lower compared to other ICIs. However, several serious cases of nervous system toxicities have been reported following atezolizumab therapy [7]. Diagnosing neurological adverse events poses a significant challenge due to often atypical clinical symptoms and laboratory findings, coupled with limited practical experience in managing ICI-related toxicities. With the increasing use of ICIs in cancer therapy, there is an anticipated rise in the incidence of neurotoxicities. Delayed recognition of these adverse events as being drug-related can exacerbate patient vulnerability to further toxicity. Currently, the literature lacks a comprehensive characterization of the clinical course and specific symptoms linked to neurological manifestations associated with atezolizumab. Here, we review atezolizumab induced neurotoxicity, aiming to describe its clinical presentation, delay of onset and resolution of symptoms, diagnostic findings, treatment options, and patient outcomes.

Methods

Search strategy

A medline search on atezolizumab induced neurotoxicity using PubMed, Science Direct, and Google Scholar databases was performed and completed on March 15, 2024.

The search strategy included MeSH terms and free-text words. Search terms included: atezolizumab, PD-L1, neurotoxicity, neurological adverse events, neurological complications, neurological immune related side effects, central nervous system, encephalitis, encephalopathy, seizures, coma, myoclonus, confusion, aphasia, ataxia, and peripheral neuropathy. Duplicates were removed and the references of the included articles were cross-checked. Studies that discussed neurotoxicity associated with all immune checkpoint inhibitors without explicitly mentioning atezolizumab were excluded. Articles studying anti-PD-L1 agents without specifying atezolizumab were also excluded. Additionally, paraneoplastic neurological manifestations induced by atezolizumab were ruled out from our review.

These exclusion criteria were implemented to ensure that our literature review focused specifically on neurotoxicity attributed to atezolizumab therapy.

Study selection

We included English-language publications encompassing all age groups, randomized clinical trials, observational studies, systematic reviews, case reports, and case series. Table 1 presents data from clinical trials and large scale retrospective studies identified in the literature. In Table 2, data from case studies and observational studies were compiled detailing patient demographics, cancer type, neurotoxic symptoms including onset and recovery timing, diagnostic procedures, co-administered chemotherapies, interventions, and clinical outcomes. Most case reports underwent thorough investigations to rule out infection, tumor progression, or other causes of neurotoxicity, attributing the majority of cases to atezolizumab. Variables were labeled as “unable to assess” if pertinent patient data were unavailable.

|

First author |

Type of study |

Peripheral neuropathy/Polyneuropathy |

Guillain Barre syndrome |

Myastenia gravis |

Hypophysitis/Pituitary disorders |

Encephalitis/Myelitis |

Meningitis |

Demyelinating disorders |

Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Mikami [23] |

Retrospective study/FAERS database |

7.9%

|

10.8%

|

4.5%

|

2.5%

|

18.8%

|

11.3% |

10.5%

|

Myositis: 6.9% Vasculitis: 11% |

|

Kichendasse [10] |

Analysis of OAK, POPLAR, BIRCH and FIR trials |

84%/9%

|

7% |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

|

Shmid [11] |

Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial |

Grade 1-2: 16% Grade 3: 6%

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

|

Johnson [24] |

Retrospective study/WHO VigiBase |

- |

4.69%

|

4.57%

|

- |

10.58%

|

11.11% |

- |

- |

|

Sato [25] |

Retrospective study/ JADER database |

3.09%

|

- |

1.14% |

0% |

21.88%

|

37.04% |

- |

Myositis: 2.36% |

|

Socinski [12] |

Randomized controlled trial |

Grade 1-2: 35.9% Grade 3-4: 2.8%

|

- |

- |

- |

-

|

- |

- |

- |

|

Hida [13] |

Phase III OAK study |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 case (grade 4) |

- |

- |

|

Rittmeyer [14] |

Phase 3, open-label, multicentre randomised controlled trial |

1% |

- |

- |

- |

-

|

- |

- |

- |

|

Cortinovis [15] |

Phase III OAK study |

- |

- |

- |

- |

0.7% |

- |

- |

|

|

Dermott [16] |

Phase Ia study |

Grade 1-2: 1% Grade 3-4: 0%

|

- |

Grade 1-2: 1% Grade 3-4: 0%

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

Ataxia (3%) Tremor (1%) Somnolence (1%) |

|

Fehrenbacher [17] |

Multicentre, open-label, phase 2 randomised controlled trial (POPLAR) |

NS |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Ning [18] |

FDA clinical trial |

NS |

- |

- |

|

× |

|

× |

Confusional state Seizure Paralysis Encephalopathy Aphasia |

|

NS: percentage not specified |

|||||||||

|

Type of study, reference |

First author, year (number of patients) |

Sex |

Age |

Type of malignant tumor |

Type of neurotoxicity |

Grade of severity |

Dosage (mg)/3 weeks |

Duration |

Number of cycles |

Delay of onset (after last cycle) |

Concurrent therapy |

Clinical symptoms |

Paraclinical investigations |

Exclusion of other causes |

Management options |

Outcome (within) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Case report [27] |

Mahjoubi, 2023 (1) |

M |

68 |

NSCLC |

Seizures |

Grade 3 |

1200 |

6 months |

7th |

21 days |

None |

sudden loss of consciousness with myoclonus of the right hemibody |

MRI, EEG and CSF: No abnormalities |

- Normal blood glucose and electrolytes levels -Negative bacterial culture -CSF cytology: no tumor cells -Viral serologies and immunological markers: negative |

Leviteracetam |

Recovery (7 days) Negative rechallenge |

|

Case report [5] |

Chao, 2023 (1) |

M |

76 |

HCC |

Encephalitis |

Grade 3 |

1200 |

2 weeks |

1st |

15 days |

bevacizumab |

altered consciousness, hypothermia, aphasia, dysarthria |

CSF: elevated cell count, protein and albumin levels MRI: normal |

Infectious, anatomical, endocrinal, and neoplastic etiologies were ruled out |

methylprednisolone 3 mg/kg/day |

Recovery (9 days) |

|

Case report [28] |

Prieto, 2023 (1) |

UA |

UA |

Lung adenocarcinoma |

NMO |

UA |

UA |

UA |

UA |

UA |

UA |

UA |

UA |

UA |

UA |

UA |

|

Case report [29] |

Prasertpan, 2023 (1) |

M |

58 |

Bladder cancer |

Striatal encephalitis |

Grade 3 |

1200 |

NS |

NS |

2 years |

None |

Subacute progressive parkinsonism |

MRI: diffuse hyperitense T2/FLAIR lesions with nodular and peripheral enhancement CSF: No abnormalities |

Serum and CSF autoimmune and paraneoplastic antibodies: unremarkable CSF cytology and metastatic workup: normal |

Two courses of IV pulse methylprednisolone 600mg of levodopa/carbidopa |

Initial improvement (1 month) Recurrence after 7-month period of remission |

|

Case report [30] |

Chen, 2023 (1) |

M |

46 |

SCLC |

Cerebellar ataxia |

Grade 2 |

1200 |

3 months |

3rd |

15 days |

Platinum + etoposide |

Dysarthria, multidirectional nystagmus, asymmetric dysmetria, slight wide-based gait |

-CSF: No abnormalities -Electrophysiological examination: slight reduction in the sensory nerve action potential |

-Serum: No antinuclear antigen antibodies -CSF: no autoantibodies associated with PNS or LE |

methylprednisolone at 1g/day for 5 days, followed by oral prednisolone 80 mg/day for 2 weeks |

Recovery (1 month) |

|

Case report [31] |

Kapagan, 2023 (1) |

M |

66 |

SCLC |

Cerebellar ataxia |

Grade 2 |

1200 |

3 months |

3rd |

UA |

None |

Cerebellar syndrome |

MRI: leptomeningeal involvement |

Blood tests and a lumbar puncture: no structural, biochemical, paraneoplastic, or infectious cause |

High-dose steroid treatment |

Recovery (20 days) |

|

Case report [32] |

Ibrahim, 2022 (1) |

F |

71 |

SCLC |

Encephalitis |

Grade 3 |

1200 |

4 months |

4th |

3 weeks |

None |

Impaired consciousness |

CSF: high cell count, protein and glucose levels MRI: no acute pathology EEG: unremarkable |

MRI: Brain metastasis CSF cultures: negative CSF cytology: no malignant cells |

high-dose of systemic steroids |

Recovery (10 days) |

|

Case report [26] |

Chen, 2022 (1) |

F |

65 |

Breast carcinoma |

Encephalitis |

Grade 5 |

1200 |

4 months |

4th |

10 days |

paclitaxel |

Coma Respiratory failure |

MRI: T2 and DWI hyperintense signals in the bilateral cerebellar hemisphere, vermis of the cerebellum, bilateral frontal, temporal and parietal lobes and occipital cortex |

Brain metastases and paraneoplastic neurological syndrome were not ruled out |

Intravenous infusion of 10 ml dexamethasone |

Death after few days due to respiratory failure |

|

Case report [33] |

Evin, 2022 (1) |

M |

64 |

SCLC |

PRES |

Grade 3 |

1200 |

1 day |

1st |

24 hours |

Carboplatin + etoposide |

Impaired consciousness, generalized seizure right hemiplegia, facial paralysis, pyramidal syndrome |

EEG: absence of seizure MRI: multiple bilateral subcortical, parietal, temporal, occipital and cerebellar T2 FLAIR high signals, predominantly in the posterior region |

CT: no evidence of stroke, bleeding or brain metastasis Autoimmune, infectious and vascular laboratory evaluation: no abnormalities |

antihypertensive and antiepileptic treatment |

Recovery (several days) Negative rechallenge |

|

Case report [7] |

Satake, 2022 (1) |

F |

42 |

HCC |

Encephalitis |

Grade 4 |

1200 |

12 days |

1st |

12 days |

bevacizumab |

High fever, peripheral sensory neuropathy, impaired consciousness, convulsion; right-sided paralysis, right hemispatial neglect, and aphasia |

CSF: elevated cell count, protein and glucose levels MRI: MERS |

influenza and SARS Cov 2 diagnostic tests: negative CSF cultures: negative Viral serologies: negative CSF cytology: no malignant cells CT: no signs of cerebral hemorrhaging MRI: no signs of cerebral infraction and no metastatic brain tumors PNS was not excluded |

Propofol, methylprednisolone 1g/day for 3 days Levetiracetam |

Initial improvement with remaining paralysis and aphasia (5 days) Death 109 days after starting ICI treatment due to tumor progression |

|

Case report [34] |

Foulser, 2022 (1) |

F |

56 |

Breast cancer |

PRES |

Grade 3 |

1200 |

6 months |

4th |

NS |

Carboplatin |

Cognitive impairment, behavioural changes, dysphasia, visual disturbance, severe hypertension |

MRI: PRES-related changes |

MRI: known cerebellar metastasis |

antiviral+antibiotic therapies amlodipine |

Recovery (21 days) |

|

Case report [35] |

Sebbag, 2022 (1) |

UA |

47 |

SCLC |

Cerebellar ataxia |

Grade 2 |

1200 |

4 omnths |

4th |

UA |

UA |

Kinetic and static cerebellar syndrome |

UA |

UA |

UA |

No clinical improvement |

|

Case report [36] |

Trontzas, 2021 (1) |

UA |

UA |

SCLC |

Enteric plexus neuropathy |

UA |

UA |

UA |

UA |

UA |

UA |

UA |

UA |

UA |

UA |

UA |

|

Case report [37] |

Esechie, 2021 (1) |

UA |

UA |

SCLC |

LETM |

Grade 3 |

1200 |

UA |

UA |

UA |

UA |

acute paralysis of the lower extremity, sensory loss from chest down with overflow incontinence |

MRI: enhancing lesions from C7–T7 |

COVID-19 vaccination one day prior to presenting symptoms |

5-day course of pulsed methylprednisolone followed by therapeutic plasma exchange for 3 days |

Minimal improvement |

|

Case report [38] |

Lu, 2021 (1) |

M |

45 |

LCNEC |

MS flare |

Grade 5 |

1200 |

3 weeks |

1st |

21 days |

None |

blurred vision, generalized weakness, confusion |

MRI: numerous new enhancing lesions within the cerebrum, cerebellum, and brainstem, bilateral enhancements of the optic sheath complexes |

CSF: oligoclonal bands without malignant cells. CSF antibodies: negative |

high-dose glucocorticoids tapered in 3 weeks |

Initial recovery Recurrence after 6-month period of remission Death 10 months after starting ICI treatment |

|

Case report [39] |

Nader, 2021 (1) |

F |

38 |

Breast cancer |

Meningoencephalitis |

Grade 3 |

1200 |

10 days |

1st |

10 days |

None |

Impaired consciousness, fever, tonico-clonic seizures |

CSF: high cell counts and protein level, inflammatory cells MRI: diffuse leptomeningeal enhancement |

Urine, and blood cultures: Negative Viral serologies: negative CT scan of the chest: no infiltrates or signs of infection CSF culture: negative CSF cytology: no malignant cells. PCR multiplex for viral infections on CSF: negative |

high dose steroids with dexamethasone 24 mg daily |

Partial improvement with remaining mild lower extremity weakness and numbness (2 weeks) Death 5 years after starting ICI treatment due to tumor progression |

|

Case report [40] |

Nishijima, 2021 (1) |

F |

72 |

NSCLC |

Encephalitis |

Grade 3 |

1200 |

9 months |

7th |

3 months |

None |

Gait disturbance, mild disturbance of consciousness |

CSF: normal cytology MRI: symmetrical high signal in the thalamus bilaterally |

Imaging: no cancer recurrence or Metastases Serum autoimmune antibodies: absent CSF: high immunoglobulin G index and positive oligoclonal bands CSF culture: negative |

steroids and IV immunoglobulin |

Partial improvement

|

|

Case report [41] |

Wada, 2021 (1) |

M |

46 |

NSCLC |

Limbic encephalitis |

Grade 3 |

1200 |

8 months |

8th |

2 months |

None |

Depressive symptoms, dyskinesia, decreased spontaneous speech, disorientation, impairment in memory |

CSF: high cell count MRI: high signal intensity in the limbic system |

MRI: no brain metastasis CSF examination: positive for anti-Hu and anti-CV2 antibodies, increased interleukin 2 level EEG: no paroxysmal discharge Low TSH and FT3 levels but no signs of inflammation regard to the pituitary gland Endocrine tests: unremarkable CSF cytology: no tumor cells CSF work-up: no signs of an infectious, autoimmune or paraneoplastic inflammation |

steroid pulse therapy and IV immunoglobulin |

Partial improvement |

|

Case report [42] |

Ozdirik, 2021 (1) |

F |

70 |

HCC |

Encephalitis |

Grade 5 |

1200 |

10 days |

1st |

10 days |

bevacizumab |

Confusion, aphasia, emesis, dyspnea, fever, adynamia, respiratory failure

|

CSF: elevated cell counts and protein level EMG: motor neuropathy MRI: normal |

MRI and CT-scan of the chest: no extrahepatic tumor manifestation No clinical or laboratory signs of hepatic encephalopathy were present Blood, urine, and sputum cultures: negative COVID 19 and influenza A and B: negative Cranial CT-scan: no signs of bleeding or ischemia Chest x-ray: normal |

methylprednisolone 1 mg/kg/day then up to 2 mg/kg/day anti-infective therapy with ceftriaxone, amoxicillin, and acyclovir plasmapherisis |

Initial recovery (21 days) Death 67 days after starting ICI treatment due to progressive tumor |

|

Single center retrospective cohort [1] |

Duong, 2021 (1) |

M |

46 |

NSCLC |

MS flare |

Grade 3 |

1200 |

NS |

1st |

NS |

None |

NS |

CSF: OCB positive serology MRI: enhancing cerebral lesions and optic nerve enhancement |

NS |

IV methylprednisolone 1 g/day for 3 days, then prednisone taper over 1 month |

Recovery |

|

Prospective cohort [43] |

Chang, 2020 (5) |

F |

37 |

Breast cancer |

Encephalitis |

Gradec3 |

1200 |

NS |

NS |

15 days |

cobimetinib |

Fever, altered mentality |

CSF: Increased cell count and protein level MRI: Diffuse leptomeningeal enhancement EEG: not performed |

NS |

Steroid, immunoglobulin |

Recovery (2 days) |

|

F |

53 |

Bladder cancer |

Encephalitis Guillain Barre syndrome |

Grade 3 |

1200 |

NS |

NS |

18 days |

None |

Fever, seizure Limb weakness, facial palsy |

CSF: Increased cell count and protein level MRI: T2 high signals in limbic and brainstem areas with leptomeningeal enhancement |

NS |

Steroid, immunoglobulin, rituximab, tocilizumab |

Recovery (6 days) |

||

|

F |

70 |

Bladder cancer |

Encephalitis Guillain Barre syndrome Myelitis |

Grade 3 |

1200 |

NS |

NS |

15 days |

None |

Fever, seizure, altered mentality Limb weakness, facial palsy Incontinence, saddle anesthesia |

CSF: Increased cell count and protein level MRI: T2 high signals in white matter (right> left) and T6 ~ T9 spinal cord |

NS |

Steroid, immunoglobulin, rituximab |

Recovery (4 days) |

||

|

M |

42 |

Bladder cancer |

Encephalitis |

Grade 3 |

1200 |

NS |

NS |

15 days |

cobimetinib |

Fever, altered mentality |

CSF: Increased cell count and protein level MRI: normal |

NS |

Steroid, IV immunoglobulin |

Recovery (5 days) |

||

|

F |

60 |

Breast cancer |

Encephalitis |

Grade 3 |

1200 |

NS |

NS |

16 days |

Fulvestrant + ipataserib |

Fever, altered mentality |

CSF: increased cell count and protein level MRI: T2 high signals in the left medial frontal gyrus with leptomeningeal enhancement |

NS |

Steroid |

Recovery (2 days) |

||

|

Single center retrospective study [44] |

Toyozawa, 2020 (3) |

F |

71 |

NSCLC |

Aseptic meningitis |

Grade 3 |

1200 |

14 days |

1st |

14 days |

Carboplatin + paclitaxel + bevacizumab |

Impaired consciousness, fever |

CSF: high protein MRI: no abnormal findings |

CSF: no malignant cells |

Steroid pulse (1000 mg × 3/day) |

Recovery (18 days) |

|

M |

50 |

Lung adenocarcinoma |

Aseptic meningitis |

Grade 3 |

1200 |

3 months |

3rd |

11 days |

None |

Impaired consciousness, fever |

CSF: increased cell counts and protein level MRI: Multiple abnormal enhancements along the lines of the corpus callosum. |

NS |

Steroid pulse (1000 mg × 3/day) Anti-epileptic drug (levetiracetam) |

Recovery (4 days) |

||

|

M |

55 |

Lung adenocarcinoma |

Aseptic meningitis |

Grade 3 |

1200 |

11 days |

1st |

11 days |

None |

Impaired consciousness, fever |

CSF: high protein MRI: no abnormalities |

NS |

Steroid pulse (1000 mg × 3 day) |

Recovery (18 days) |

||

|

Case report [45] |

Ogawa, 2020 (1) |

M |

56 |

NSCLC |

Aseptic meningitis |

Grade 3 |

1200 |

11 days |

1st |

11 days |

None |

Fever, headache, fatigue |

CSF: increased cell counts and protein level MRI: meningeal enhancement |

CSF: no cancer cells and non-specific inflammation suggestive of meningitis CSF cultures and serological tests: negative |

IV methyl-prednisolone 1g/day for 3 days then prednisone taper over 12 weeks |

Recovery (7 days) |

|

Case report [8] |

Kichloo, 2020 (1) |

F |

68 |

SCLC |

Bell’s palsy |

Grade 2 |

1200 |

5 months |

5th |

15 days |

None |

right-sided facial droop and numbness |

MRI: No abnormalities |

No vesicular eruption consistent with HSV or VZV reactivation HIV testing: negative CT scan: no signs of bleeding Metabolic panel: no abnormalities Calcium, vitamin D, TSH and folate levels: normal limits CT-angiogram: no thrombotic occlusion Echocardiogram: normal |

14-day tapering course of oral prednisone, starting at 60 mg |

Recovery (1 month) Negative rechallenge |

|

Case report [6] |

Yamaguchi, 2020 (1) |

M |

56 |

Lung adenocarcinoma |

Encephalitis |

Grade 3 |

1200 |

17 days |

1st |

17 days |

Carboplatin + nab-paclitaxel |

Disturbance of consciousness, high fever, motor aphasia |

CSF: high cell count, and protein level MRI: normal |

CSF: increased interleukin 6 level CSF bacterial culture: negatvie PCR for HSV 1 and 2 and CMV: negative Serum antibody tests for paraneoplastic neurological syndrome: negative |

steroid pulse with 1g/day of methylprednisolone for 3 days then oral administration of prednisolone 0.5 mg/kg/day |

Recovery (16 days) |

|

Case report [46] |

Robert, 2020 (1) |

F |

48 |

Lung adenocarcinoma |

Encephalitis |

Gradde 3 |

1200 |

13 days |

1st |

13 days |

None |

Fever, psychomotor slow-down, memory impairment, aphasia |

CSF: increased cell count, protein and glucose levels MRI: Pachy- and leptomeningeal enhancement |

CSF: no malignant cells

|

Methylprednisolone 1 g/day for 3 days, then 1 mg/kg/dayy for 1 month followed by gradual decrease |

Recovery (11 months) Negative rechallenge with pembrolizumab |

|

Single center retrospective cohort [47] |

Vogrig, 2020 (1) |

NS |

NS |

SCLC |

Cerebellar ataxia |

Grade 3 |

1200 |

NS |

NS |

NS |

NS |

gait ataxia, rotatory nystagmus, nausea |

No abnormalities |

NS |

NS |

Partial clinical improvement |

|

Single center retrospective case series [48] |

Francis, 2020 (1) |

F |

73 |

RCC |

Optic neuritis |

Grade 2 |

1200 |

NS |

95th |

21 days |

None |

“Big” Floaters optic nerve edema

|

MRI: No abnormalities |

NS |

prednisone 80 mg/day for 1 week taper over 2 months |

NS |

|

Case report [49] |

Samanci, 2020 (1) |

M |

53 |

Lung adenocarcinoma |

Optic neuritis |

Grade 3 |

1200 |

20 days |

1st |

20 days |

None |

blurred vision, double vision, headache, and general fatigue, |

Fundus examination: optic disc edema BCVA: 20/80 in left eye and 20/40 in right eye |

MRI: brain metastasis/ no abnormalities in the pituitary body HSV types 1 and 2 and VZV serology: negative ACTH, TSH, free T4, and cortisol levels: normal |

IV methylprednisolone 2 mg/kg followed by oral methylprednisolone |

Partial recovery (2 months) |

|

Case report [50] |

Thakolwiboon, 2019 (1) |

M |

87 |

Urothelial carcinoma |

MG |

Grade 5 |

1200 |

NS |

2nd |

NS |

NS |

diplopia, ptosis, proximal muscle weakness and nasal voice |

ECG: new right bundle branch block and left anterior fascicular block |

MRI: no stroke or brain metastasis CT of the chest: no thymoma Antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, cyclic citrulline peptide, SS-A, SS-B, proteinase-3, and myeloperoxidase antibodies: negative Myositis antibidies: undetectable |

Prednisone 60 mg daily for 1 week, IV immunoglobulin 0.4 g/kg daily pyridostigmine |

Death due to cardiac arrest |

|

Single center retrospective study [51] |

Yuen, 2019 (1) |

M |

65 |

Urothelial carcinoma |

Facial palsy + neuropathy |

Grade 2 |

1200 |

3 weeks |

NS |

15 days |

None |

Peripheral right facial palsy Weakness, burning pain, tringling sensation in the legs and hands |

MRI: normal CSF: No abnormalities EMG: Cervical and lumbar polyradiculopathy |

NS |

prednisone 60 mg per day and then tapered |

Recovery with remaining mild residual tingling in the toes (1 week) |

|

Case report [52] |

Kim, 2019 (1) |

M |

49 |

Bladder cancer |

Encephalitis |

Grade 5 |

1200 |

14 days |

1st |

14 days |

None |

Impaired consciousness, stupor, generalized tonic-clonic seizures |

CSF: Increased cell count MRI: Diffuse leptomeningeal enhancement |

CSF: no malignant cells, paraneoplastic antibodies, bacterial culture, fungus culture, tuberculous PCR, and viral PCR: negative EEG: no epileptiform discharge |

Dexamethasone, IV immunoglobulin |

Death 98 days after starting ICI treatment due to septic shock |

|

Retrospective study/FAERS database [53] |

Garcia, 2019 (1) |

F |

49 |

Colon adenocarcinoma |

MS flare |

NS |

1200 |

2 weeks |

1st |

15 days |

cobimetinib |

Fever, progressive confusion |

MRI: nonspecific T2 hyperintense lesions within the subcortical, deep, and periventricular white matter |

NS |

high-dose corticosteroids |

Death 1 month after starting ICI treatment due to progressive disease |

|

Case report [54] |

Chae, 2018 (1) |

F |

67 |

Lung adenocarcinoma |

MG relapse |

Grade 4 |

1200 |

6 weeks |

2nd |

Several days |

None |

Dyspnea, dysphagia, weakness, hypercapnic respiratory failure |

NS |

NS |

Prednisone, pyridostigmine, VNI, plasmapherisis |

Recovery |

|

Case report [55] |

Tan, 2018 (1) |

M |

66 |

Lung adenocarcinoma |

Cerebellar ataxia |

Grade 2 |

1200 |

8 months |

NS |

6 months |

Carboplatin + pemetrexed |

ataxic wide-based gait |

CSF: acellular with normal proteinand glucose levels MRI: small vessel disease only

|

CT head with contrast: normal Blood tests: normal Paraneoplastic screen: negative CSF culture and viral PCR: negative |

Prednisolone 1mg/kg |

Initial improvement (1 week) Death 5 months due to progressive metastatic disease |

|

Case report [56] |

Mori, 2018 (1) |

M |

64 |

NSCLC |

Optic neuritis+ hypopituitarism |

Grade 2 |

1200 |

12 months |

NS |

NS |

None |

Sudden visual loss, optic disc edema, venous congestion, weakened direct reaction of light reflex |

BCVA: 0.01 Fluorescein angiography: dye leakage MRI: high-intensity lesion in the optic nerve |

Anti-aquaporin-4 antibodies: absent Pituitary body: no abnormalities HSV and VZV antibody titers: not elevated CSF: no signs of infectious or demelinating diseases ACTH, free T4, and cortisol, TSH, GH levels: normal FSh and prolactin levels: elevated |

methylprednisolone 1 g/day for 3 days followed by 30 mg oral prednisolone |

Recovery (24 months) |

|

Case report [57] |

Laserna, 2018 (1) |

F |

53 |

CSCC |

Encephalitis |

Grade 3 |

1200 |

13 days |

1st |

13 days |

Bevacizumab |

Headache, meningeal signs, impaired cnsciousness |

CSF: high cell count, protein and glucose levels EEG: non-convulsive status epilepticus MRI: Diffuse leptomeningeal enhancement |

Head CT scan: no abnormalities CSF culture and viral serology: negative Paraneoplastic antibodies: negative |

High-dose steroids |

Recovery with remaining weakness (15 days) |

|

Case report [58] |

Arakawa, 2018 (1) |

M |

78 |

Lung adenocarcinoma |

Encephalitis |

Grade 3 |

1200 |

13 days |

1st |

13 days |

None |

Confusion, fever |

CSF: high cell counts and protein level MRI: normal |

CSF culture and viral serology: negative Paraneoplastic antibodies: negative |

steroid pulse |

Recovery (58 days) |

|

Case report [9] |

Levine, 2017 (1) |

F |

59 |

Bladder cancer |

Encephalitis |

Grade 3 |

1200 |

12 days |

1st |

12 days |

None |

Confusion, fatigue, spastic tremors, vomiting |

CSF: normal MRI: isolated frontal metastasis |

CSF culture and viral serology: negative Paraneoplastic antibodies: negative Blood and urine cultures: negative |

dexamethasone 10mg IV every 6 hours. methylprednisolone 1mg/kg/day with taper over 4-6 weeks |

Partial Reovery with remaining upper extremety weakness (5 days) Death 1 month after discharge due to progressive disease |

|

NSCLC: Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer; HCC: Hepatocellular Carcinoma; CSF: Cerebrospinal Fuid; MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging; UA: Unable To Access; NMO: Neuromyelitis Optica; NS: Not Specified; IV: Intravenous; SCLC: Small Cell Lung Cancer; PNS: Paraneoplastic Neurological Syndrome; LE: Limbic Encephalitis; PRES: Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome; CT: Computed Tomography; MERS: Mild Encephalitis/Encephalopathy with a Reversible Splenial Lesion; SARS Cov 2: Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2; ICI: Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor; LETM: Longitudinal Extensive Transverse Myelitis; LCNEC: Large Cell Neuroendocrine Carcinoma of the Lung; MS: Multiple Sclerosis; PCR: Polymerase Chain Reaction; EMG: Electromyogram; FAERS: Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System; OCB: Oligoclonal Bands; HSV: Herpes Simplex Virus; VZV: Varicella Zoster Virus; CMV: Cytomegalovirus; BCVA: Best-Corrected Visual Acuity; ACTH: Adrenocorticotropic Hormone; TSH: Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone; GH: Growth Hormone; FSH: Follicle-Stimulating Hormone; CSCC: Cervical Squamous Cell Carcinoma; MG: Myasthenia Gravis; ECG: Electrocardiogram; NIV: Non Invasive Ventilation |

||||||||||||||||

Results

A total of 56 articles were identified. Among these, 13 were clinical trials and only one was a prospective cohort study, while the remainder were retrospective data. This included 32 single-case reports, 1 case series, and 9 retrospective studies.

Controlled data from clinical trials and meta-analysis [10-22]

An analysis of data from controlled clinical trials shows that atezolizumab has a favorable safety profile. The most common adverse reactions (≥ 20%) included fatigue, nausea, urinary tract infection, fever, and constipation. The risk of adverse effects with atezolizumab is comparable to other chemotherapeutic agents and aligns with the incidence rates observed for other approved immune checkpoint inhibitors like pembrolizumab and nivolumab [12,18]. Immune-related adverse events (irAEs), including neurotoxicity, observed in patients treated with atezolizumab were predominantly low grade and manageable, with only a small number necessitating dose interruption or discontinuation alongside corticosteroid treatment. Both the POPLAR and OAK trials demonstrated favorable tolerability of atezolizumab compared to docetaxel, with a lower proportion of patients experiencing grade 3 or 4 treatment-related side effects [14,17]. Specifically, only 2.1% of irAEs in the atezolizumab group required treatment discontinuation [15]. Another Japanese patient study also revealed comparable rates of all-grade treatment-related adverse events between atezolizumab and docetaxel groups, albeit with fewer grade 3-4 events in the atezolizumab cohort [13]. Notably, neurological immune-related adverse events (irAEs), particularly neuropathy, have emerged as significant concerns in most previous clinical trials [10]. Peripheral neuropathy occurred approximately in 7% of patients in the atezolizumab group vs 1% in the placebo group [11,12,14]. Conversely, in the Japanese study, no cases of peripheral sensory neuropathy were reported, while serious neurological adverse effects such as meningoencephalitis and Guillain-Barre syndrome occurred in the atezolizumab group but were absent in the docetaxel group [13]. Notably, encephalitis was not reported as an irAE in earlier phases of POPLAR trials [17] but occurred at a low rate in subsequent studies, 0.8% and 0.3% in the OAK trial and the Impower 150 study, respectively [12,14]. Mikami’s analysis indicates that meningoencephalitis was the most common neurological complication associated with atezolizumab, occurring in 30.3% of cases, followed by Guillain-Barre syndrome and demyelinating disorders, each accounting for about 10.5% of cases. The least frequent complication was hypophysitis, occurring in 2.5% of cases [23]. Overall, the controlled data from these trials indicate a manageable safety profile for atezolizumab, with distinct advantages over traditional chemotherapy agents.

Overall incidence and severity of atezolizumab-induced neurotoxicities

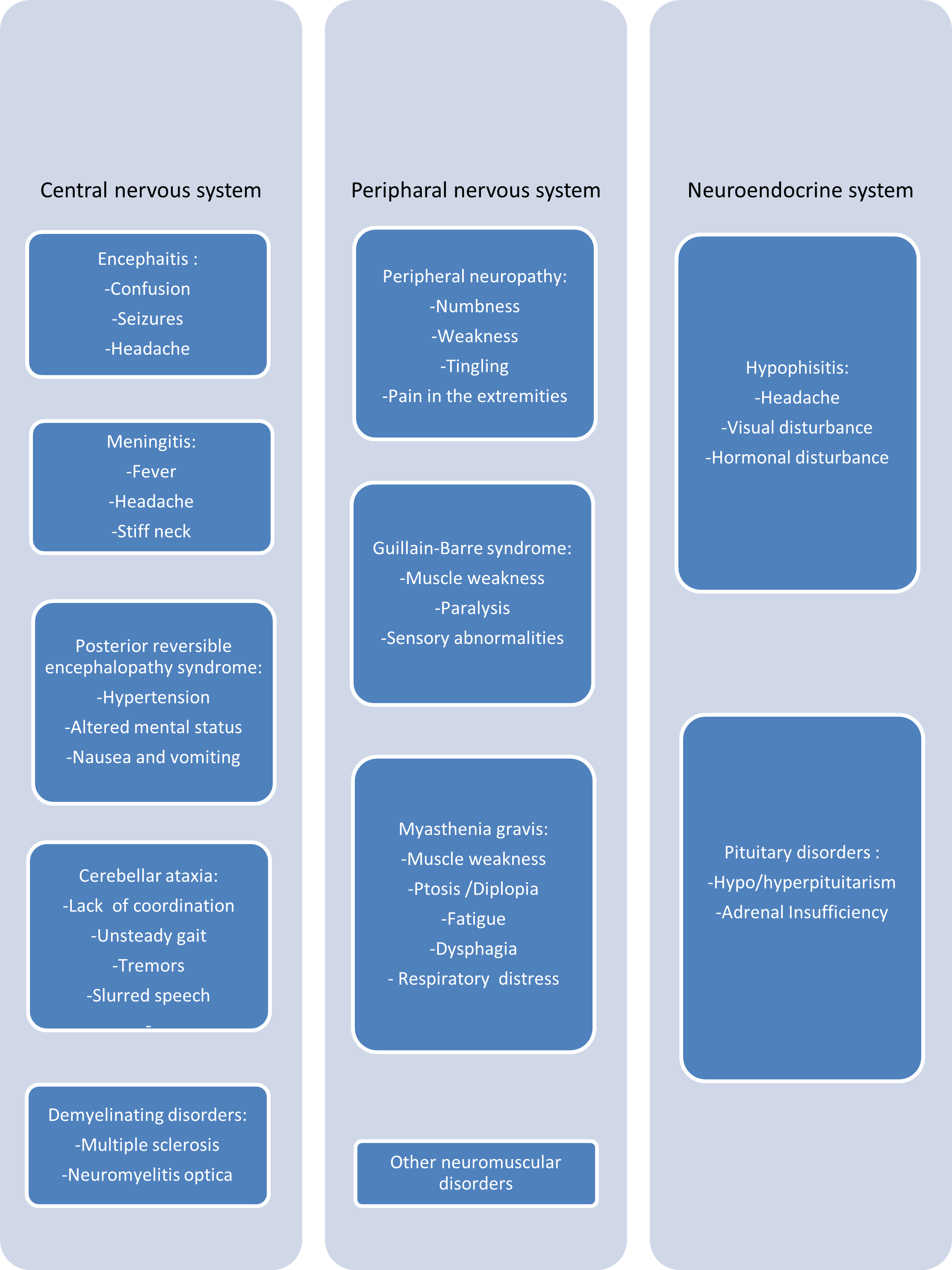

Neurological adverse events associated with atezolizumab exhibit diverse clinical presentations affecting various parts of the nervous system (Figure 1). The most frequently reported manifestations are grades 1-2 neurotoxicities, often presenting as nonspecific symptoms, such as asthenia, headaches, dizziness, paresthesias, or dysgeusia [26]. Grades 3-4 neurological syndromes are less commonly reported and encompass severe conditions such as encephalitis, encephalopathy, aseptic meningitis, myelitis, neuropathy, Guillain-Barre syndrome, myasthenia gravis, and demyelinating disorders [7,26].

Figure 1. Summary of neurological manifestations induced by atezolizumab.

Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of patient cases of atezolizumab-induced neurotoxicities reported in literature

Table 1 documented 39 studies detailing grade 3 and 4 neurotoxicities induced by atezolizumab, involving a total of 45 patients [1,5-9,26-58]. Conclusions regarding clinical characteristics can be drawn from the data provided for these patients. The demographic profile of patients experiencing atezolizumab-induced neurotoxicity revealed a male predominance (46.7%) with a median age of 58 years (range 37–87). The primary tumor localizations varied with lung being the most common (n = 26) followed by bladder (n = 9), breast (n=4), liver (n=3), kidney (n=1), colon (n=1) and cervix (n = 1). Atezolizumab dosage was consistent across cases, administered at 1200 mg every three weeks. Symptoms of neurological toxicity typically manifested after the first cycle of atezolizumab therapy (37.8% of cases), with a median onset occuring 2 weeks after the last dose (range: 1day-1year). Six documented cases had a history of neurological disorders, including three with brain metastases [9,32,49], and four with preexisting demyelinating diseases [1,36,53,54]. Co-administration of chemotherapeutic drugs, notably bevacizumab, carboplatin, paclitaxel, and cobimetinib, was common in nearly half of the cases. Atezolizumab was discontinued in all published cases and treatment of neurotoxicities varied, including corticosteroids, antiepileptic drugs, empiric antimicrobial therapy, intravenous immunoglobulin, and plasmapherisis. Symptoms typically resolved within a median of 10 days after cessation of atezolizumab (range: 2days-2years) with partial or complete recovery noted in the majority of cases (82.6%). Atezolizumab rechallenge was successful in three cases [8,27,33] while one case reported negative rechallenge with pembrolizumab [46]. Recurrence of symptoms despite withdrawal of atezolizumab after a period of remission occurred in two cases [29,38]. Fatal outcomes were observed in 10 cases [7,9,26,38,39,42,50,52,53,55], however, definitively attributing neurotoxicities as the cause of death was challenging due to initial symptom improvement upon drug discontinuation and incomplete exclusion of disease progression in some cases. The neurotoxicities underlying fatal outcomes included encephalitis (n=6), multiple sclerosis (n=2), and single cases of myasthenia gravis and cerebellar ataxia.

Published cases of atezolizumab induced neurotoxicity (Table 1) encompassed various neurological manifestations, with encephalitis being the most common (39.6%), followed by cerebellar ataxia (10.4%), meningitis (8.3%), optic neuritis (6.3%), multiple sclerosis flare (6.3%), posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (4.2%), peripheral neuropathy (4.2%), Guillain-Barre syndrome (4.2%), myasthenia gravis relapse (4.2%), myelitis (4.2%), facial palsy (4.2%) and neuromyelitis optica (2.1%). Additionally, other neurological adverse events were reported in clinical trials and large-scale retrospective pharmacovigilance studies, including aphasia, hypophisitis, and paralysis.

Types of neurological adverse effects associated with atezolizumab

Encephalitis: Among CNS neurotoxicities associated with atezolizumab, encephalitis stands out as a rare yet potentially fatal adverse reaction [7]. The incidence rate of encephalitis following atezolizumab therapy, as reported in the OAK trial, was only 0.8% in patients with NSCLC [5].

At the time of this article, our review included 19 published cases of encephalitis following atezolizumab therapy (Table 1), with a few additional cases mentioned in clinical trials and large scae retrospective studies (Table 2). The presentation of atezolizumab-induced encephalitis revealed typical features but was also demonstrated heterogeneity, encompassing symptoms such as fever, headache, confusion, gait instability, seizures, and in rare instances, meningeal signs. The onset of symptoms varied; with most cases occuring between 10 and 21 days after atezolizumab administration, though some cases presented much later, such as nine months post-administration [40]. Common CSF features include pleocytosis and elevated protein levels while MRI findings often revealed leptomeningeal enhancement or brain parenchymal lesions although pathological findings in imaging were absent in some cases. Management of encephalitis linked to ICI treatment remains uncertain; however favorable responses to steroid therapy were observed in 14 of our cases. Only a small number of patients required intravenous immunoglobulin [40,41,43,50,52] or plasmapheresis [42]. It's worth noting that in 2022, we documented a case involving a patient with SCLC who experienced recurrent seizures 21 days after completing the seventh cycle of atezolizumab treatment. Extensive investigations ruled out the diagnosis of encephalitis and the patient's symptoms were successfully managed with leviteracetam, leading to complete recovery within a week. Atezolizumab was subsequently reintroduced after a one-month period of remission without any recurring neurological symptoms [27].

Aseptic meningitis: Aseptic meningitis occurs in approximately 0.1–0.2% of patients treated with ICIs. Within our review, we identified four cases of aseptic meningitis induced by atezolizumab [44,45]. Additionally, two other studies have reported cases of meningitis associated with atezolizumab. Aseptic meningitis typically manifested between 11 to 14 days following the initial administration of atezolizumab in three cases, while in the fourth case, it occurred 11 days after the third dose. Fever could signal the onset of meningitis. Other common symptoms included altered consciousness and headache. CSF analysis revealed lymphocytic meningitis and high protein level accompanied by meningeal enhancement observed on MRI scans. All documented cases of aseptic meningitis are fully resolved with the administration of steroids and cessation of atezolizumab treatment.

Encephalopathy: Two cases of posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) occurring in patients receiving atezolizumab have been documented in the literature [33,34]. Symptoms manifested differently in each case: one patient experienced symptoms 24 hours after the first dose, while the other developed symptoms 6 months after the fourth cycle. Neurological manifestations included altered consciousness, visual disturbances, focal neurological deficits, seizures, and typical imaging alterations primarily affecting the posterior parietal and occipital lobes on MRI. Notably, both patients were presented with elevated blood pressure at the time of PRES diagnosis: 206/108 mmHg in a patient undergoing atezolizumab treatment for small cell lung cancer [33] and 169/81 mmHg in another patient treated for breast cancer [34]. In both case reports, there was marked neurological improvement following antihypertensive therapy in the subsequent days.

Cereballar ataxia: In our review, we identified five cases of acute cerebellar ataxia induced by atezolizumab. Furthermore, ataxia was previously reported in a phase 2 clinical trial [16]. The time lapse between the initiation of atezolizumab and the onset of ataxia was unspecified in most cases, except for one instance where ataxia appeared two weeks after starting atezolizumab. Symptoms of cerebellar syndrome observed in the documented cases included gait disturbances, ataxia, dysarthria, nystagmus, and nausea. Treatment typically involved corticosteroids, leading to complete recovery in two cases, partial improvement in one case and initial improvement within one week followed by eventual death due to metastatic disease in another case [55]. Unfortunately, no clinical improvement was observed in the remaining case [35].

Peripheral neuropathy: Peripheral neuropathy is a prominent aspect of the literature concerning ICI-associated neurotoxicity, although it has been described as a complication of atezolizumab primarily in clinical settings. Both sensory and motor peripheral neuropathies have been documented, presenting in acute or chronic forms. Within our review, we encountered a case report highlighting enteric plexus neuropathy; however, patient characteristics were inaccessible [36]. In another instance, a patient developed peripheral neuropathy associated with facial palsy two weeks after completing the last cycle of atezolizumab. Symptoms resolved within seven days, but residual paresthesia persisted in the toes [51].

Guillain Barre syndrome (GBS): GBS induced by ICI is a rare occurence, with only a few reported cases in the literature. In a prospective cohort study, two cases of Guillain-Barré syndrome induced by atezolizumab were documented [43]. The presentation was typical, characterized by limb weakness and facial palsy. Symptoms appeared 15 and 18 days, respectively, after receiving atezolizumab treatment. Both patients were treated with intravenous immunoglobulin and corticosteroids. Atezolizumab was discontinued in both instances, and complete recovery was achieved within a few days of initiating steroid therapy.

Paralysis: Our review identified two cases of paralysis induced by atezolizumab [8,51]. In both instances, patients developed peripheral facial palsy after two weeks of atezolizumab therapy. Symptoms resolved in both patients after discontinuation of atezolizumab. Interestingly, in one case, there was no recurrence of symptoms upon rechallenge. Additionally, two other patients with Guillain-Barre syndrome experienced cranial nerve palsy [43]. Paralysis was also observed in a previous clinical trial [18].

Multiple sclerosis (MS): In our review, we identified three MS patients who experienced relapse while undergoing treatment with atezolizumab. The history of MS was confirmed in all instances. Among these cases, two patients developed encephalopathic symptoms during their relapse [1,53], accompanied by blurred vision and weakness in one case [38]. The median onset of symptoms was 15 days. Imaging results were consistent with typical MS manifestations in all patients. Corticosteroids were administered in every case. Unfortunately, a fatal outcome was observed in two patients, while the remaining case achieved complete recovery.

Optic neuritis (ON): In the literature, ON has been reported following atezolizumab treatment. Three cases were included in our review. The onset of symptoms occurred three weeks after treatment initiation in two cases [48,49], while in the remaining case, ON manifested after 12 months [56]. Optic neuritis tended to be bilateral in most cases. MRI findings showed optic nerve enhancement abnormalities in only one case. Corticosteroids were administered to all three patients. Resolution of symptoms was observed in two cases, while the outcome of the remaining patient was not specified.

Myasthenia gravis (MG): The most frequently reported neuromuscular disorder associated with ICIs is MG. It can manifest either as de novo or as an exacerbation of pre-existing myasthenia. However, only two case reports of atezolizumab induced MG were found in the literature. Chae et al. reported a case of MG exacerbation emerging six weeks after initiating atezolizumab [54]. The progression was further complicated by hypercapnic respiratory failure, requiring intubation. However, stability was achieved following five sessions of plasmapheresis. Additionally, Thakolwiboon et al. documented a case of new onset MG following atezolizumab therapy, which resulted in fatal outcome due to cardiac arrest [50]. In addition to the neurotoxicities mentioned earlier, our review revealed one case each of longitudinal extensive transverse myelitis [37] and neuromyelitis optica [28].

Discussion

Clinical understanding of the toxic effects of ICIs remains relatively limited [1]. Due to the relatively low occurrence of ICI-related neurologic adverse events, there is limited data available, with most of these adverse effects documented in case reports. The majority of published reviews and large-scale studies have examined immune checkpoint inhibitors collectively, rather than focusing solely on any particular agent. This systematic review is the first to describe various types of neurotoxicities induced by atezolizumab and detail the range of symptoms, diagnosis features, and timing of onset and resolution.

Characteristics of atezolizumab-induced neurotoxicity

Encephalitis emerges as the most extensively studied neurotoxicity associated with atezolizumab therapy [4]. However, findings from clinical trials indicate that peripheral neuropathies are the most prevalent among observed neurological adverse events. In patients receiving atezolizumab, neurologic irAEs were most commonly observed in those with lung cancer [23]. In our review, the mean age of patients who developed atezolizumab-related multiple sclerosis (MS) flare-ups and ataxia were the youngest (46.7 and 56.25 years, respectively), while patients with myasthenia gravis and encephalitis were the oldest (77 and 60 years, respectively) [23]. Symptoms of atezolizumab associated neurotoxicity often exhibit a delayed onset, typically appearing around 15 days after drug initiation. However, in some instances, neurological toxicities occur much later, with rare cases emerging beyond 2 months after the start of atezolizumab treatment. Nearly all cases occur shortly after the first dose, with no instances reported following drug cessation. Atezolizumab-related multiple sclerosis or meningitis occurred significantly earlier (median of 15 days) compared to other neurologic irAEs.The broad range of onset times for neurological toxicity may compound clinicians' challenges in identifying and diagnosing atezolizumab-related neurotoxicity. MRI abnormalities are observed in almost all patients; however, certain findings lack specificity and could potentially signify alternative underlying causes. Neurological events are progressive unless drug discontinuation or interruption is initiated. Management of severe neurological events involves temporary immunosuppression utilizing steroids or alternative agents such as intravenous immunoglobulins, plasmapheresis, or in some cases, rituximab. These interventions lead to clinical resolution or improvement of symptoms in the majority of cases.

Comparison of neurological adverse effects between atezolizumab and other immune checkpoint inhibitors

The reported incidence and time course of irAEs in clinical trials have varied depending on the type of ICIs used. A recent meta-analysis identified atezolizumab as having the best safety profile [10,20,39]. Other studies reported an incidence of neurologic irAEs up to 5% with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors, and 12.7% with CTLA-4 inhibitors [23]. Moreover, anti-CTLA-4 agents have been associated with higher severity of irAEs. Clinical trials and meta-analyses report grade 3 or 4 neurologic adverse events occurring in 0.3–0.8% of patients under anti-CTLA-4 (ipilimumab) therapy, 0.2–0.4% under anti-PD-1 (nivolumab or pembrolizumab) treatment, and 0.1–1% under anti-PDL-1 (atezolizumab) treatment. Combined ipilimumab and nivolumab treatment increases the incidence of grade 3 and 4 neurologic adverse events to 0.7%. Anti-PD-1/L1 therapy is more frequently associated with myasthenic syndromes and less common in meningitis and cranial neuropathies, while anti-CTLA-4 therapy is more frequent in meningitis and less common in encephalitis and myositis [59]. In patients on anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 monotherapies, neurologic AEs were most commonly observed in those with non-small cell lung cancer. In contrast, in patients on anti-CTLA-4, neurologic AEs were most commonly observed in those with melanoma [23]. Notably, no cases of melanoma were found in our review. Anti-PD-L1 monotherapy, predominantly atezolizumab, was associated with an earlier onset of neurologic adverse events compared to anti-PD-1, anti-CTLA-4, and combination therapies [23]. Concerning ICI dosage, there is no clear relationship between the incidence of neurologic adverse events and drug dosage with anti-CTLA-4 antibodies. However, findings are inconsistent for anti-PD-1 agents, with increased neurological adverse events at 10 mg/kg nivolumab compared to lower doses, but the reverse observed with pembrolizumab [60]. Studies regarding anti-PDL1 inhibitors are lacking, with no available data on the correlation between atezolizumab and treatment dosage or schedule. Interestingly, age, sex, and metastatic status were not significant risk factors for overall neurologic ICI-related AEs [23].

Possible mechanisms of immune checkpoint inhibitors-induced neurotoxicity

The exact pathophysiology of ICI-associated neurotoxicity remains unclear, with multiple proposed mechanisms. First, increased T-cell activity against antigens shared by cancerous and healthy tissues potentially leads to an exaggerated inflammatory response and autoimmune neurologic damage due to unregulated T-cell activation against nerves [8]. Second, immunotherapeutic agents may elevate levels of inflammatory cytokines and trigger augmented complement-mediated inflammation by binding antibodies against PD1 and CTLA-4 expressed in normal tissue. Notably, studies have shown correlations between the presence of autoantibodies, particularly antineuronal antibodies, and improved survival but increased neurological toxicity in patients treated with checkpoint inhibitors [46]. Third, genetic susceptibility was suggested by a cohort study where the HLA-B27:05 genotype was over-represented in patients who developed autoimmune encephalitis after receiving atezolizumab [32].

Strengths: This study highlights uncommon but serious irAEs arising from immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs). It represents the largest review of patients who developed neurological irAEs from an anti-PD-L1 inhibitor; atezolizumab. This review provides a comprehensive analysis of atezolizumab-induced neurotoxicity by meticulously compiling epidemiological and clinical characteristics from case reports and retrospective studies. It covers the spectrum of neurological adverse effects, their time course, diagnostic investigations, management options, and outcomes. Additionally, it includes a comparative analysis of the safety profiles between atezolizumab and other immune checkpoint inhibitors, as well as discussions on potential mechanisms. The strength of this review lies in its thoroughness and the novel insights it offers, particularly in identifying patterns and providing a detailed comparison of adverse effects. This information is crucial for clinicians to better understand, anticipate, and manage neurotoxic effects in patients treated with atezolizumab.

Limitations: Several limiting features of this review deserve comment. With the exception of one prospective cohort study, published data available are limited to case series, single-case reports, and retrospective pharmacovigilance studies. The characteristics of these studies restrict our systematic review to descriptive reporting and preclude an examination of risk factors. The observational design of reports describing treatment for atezolizumab neurotoxicity precludes any statement about the efficacy of any specific strategy. Distinguishing atezolizumab-induced neurotoxicity from many conditions present in critically ill patients remains clinically challenging, and concurrent diagnoses may confound its identification. In fact, cancer patients commonly exhibit neurological complications such as brain metastasis, paraneoplastic syndrome and cerebrovascular disorders. Adding to this complexity, chemotherapeutic agents and radiation therapy may also be risk factors for neurotoxicity. Many questions remain regarding the true incidence and scope of atezolizumab-associated neurotoxicity. Further research evaluating atezolizumab adverse effects may provide vital information to determine key trends. Prospective evaluations with more standard and rigorous datasets are needed.

Recommendations: While our systematic review provides valuable insights into the neurotoxicity associated with atezolizumab, it is evident that further research is needed to address several important recommendations. Prospective registries collecting standardized clinical data, controlled trials comparing neurotoxicity profiles among different checkpoint inhibitors, and deeper investigations into the pathophysiology of neurotoxic syndromes are crucial steps to better understand and manage these adverse effects. Additionally, future case reports should aim to include severity grading of events and rigorously exclude alternative causes to strengthen causal conclusions. Larger retrospective analyses pooling detailed clinical data internationally could further elucidate risk factors and outcomes associated with specific treatment strategies. Embracing these recommendations will undoubtedly contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of this serious adverse drug reaction.

Conclusion

Given that case reports have documented atezolizumab-induced neurotoxicity across diverse cancer types, it is imperative to establish a comprehensive safety profile for this agent. Further investigations could enhance our understanding of which patients are at risk and how we can safely manage this serious adverse reaction.

References

2. Cheng K, Wang Y, Zhou Y, Xia R, Tang L, Liu J. Neurological Adverse Events Induced by Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Current Perspectives and New Development. Clin Med Insights Oncol. 2021 Nov 24. ;15:11795549211056261.

3. Brito MH. Neurologic adverse events of cancer immunotherapy. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2022 May;80(5 Suppl 1):270-280.

4. Wang DY, Salem JE, Cohen JV, Chandra S, Menzer C, Ye F, Zhao S, et al. Fatal Toxic Effects Associated With Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2018 Dec 1;4(12):1721-28.

5. Chao KH, Tseng TC. Atezolizumab-induced encephalitis with subdural hemorrhage and subarachnoid hemorrhage in a patient with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Formos Med Assoc. 2023 Nov;122(11):1208-12.

6. Yamaguchi Y, Nagasawa H, Katagiri Y, Wada M. Atezolizumab-associated encephalitis in metastatic lung adenocarcinoma: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2020 Jul 4;14(1):88.

7. Satake T, Maruki Y, Kubo Y, Takahashi M, Ohba A, Nagashio Y, et al. Atezolizumab-induced Encephalitis in a Patient with Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Case Report and Literature Review. Intern Med. 2022 Sep 1;61(17):2619-23.

8. Kichloo A, Albosta MS, Jamal SM, Aljadah M, Wani F, Selene I, et al. Atezolizumab-Induced Bell's Palsy in a Patient With Small Cell Lung Cancer. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2020 Jan-Dec;8:2324709620965010.

9. Levine JJ, Somer RA, Hosoya H, Squillante C. Atezolizumab-induced Encephalitis in Metastatic Bladder Cancer: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2017 Oct;15(5):e847-9.

10. Kichenadasse G, Miners JO, Mangoni AA, Rowland A, Hopkins AM, Sorich MJ. Multiorgan Immune-Related Adverse Events During Treatment With Atezolizumab. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2020 Sep;18(9):1191-9.

11. Schmid P, Rugo HS, Adams S, Schneeweiss A, Barrios CH, Iwata H, et al. IMpassion130 Investigators. Atezolizumab plus nab-paclitaxel as first-line treatment for unresectable, locally advanced or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (IMpassion130): updated efficacy results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020 Jan;21(1):44-59.

12. Socinski MA, Jotte RM, Cappuzzo F, Orlandi F, Stroyakovskiy D, Nogami N, et al. IMpower150 Study Group. Atezolizumab for First-Line Treatment of Metastatic Nonsquamous NSCLC. N Engl J Med. 2018 Jun 14;378(24):2288-301.

13. Hida T, Kaji R, Satouchi M, Ikeda N, Horiike A, Nokihara H, et al. Atezolizumab in Japanese Patients With Previously Treated Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: A Subgroup Analysis of the Phase 3 OAK Study. Clin Lung Cancer. 2018 Jul;19(4):e405-15.

14. Rittmeyer A, Barlesi F, Waterkamp D, Park K, Ciardiello F, von Pawel J, Gadgeel SM, et al. Atezolizumab versus docetaxel in patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (OAK): a phase 3, open-label, multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2017 Jan 21;389(10066):255-65.

15. Cortinovis D, von Pawel J, Syrigos K, Mazieres J, Dziadziuszko R, Fehrenbacher L, et al. Immune-related adverse events (irAEs) in advanced NSCLC patients treated with atezolizumab: Safety population analyses from the Ph III study OAK. Annals of Oncology. 2017 Sep 1;28:v468.

16. McDermott DF, Sosman JA, Sznol M, Massard C, Gordon MS, Hamid O, et al. Atezolizumab, an Anti-Programmed Death-Ligand 1 Antibody, in Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma: Long-Term Safety, Clinical Activity, and Immune Correlates From a Phase Ia Study. J Clin Oncol. 2016 Mar 10;34(8):833-42.

17. Fehrenbacher L, Spira A, Ballinger M, Kowanetz M, Vansteenkiste J, Mazieres J, et al. POPLAR Study Group. Atezolizumab versus docetaxel for patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (POPLAR): a multicentre, open-label, phase 2 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016 Apr 30;387(10030):1837-46.

18. Ning YM, Suzman D, Maher VE, Zhang L, Tang S, Ricks T, et al. FDA Approval Summary: Atezolizumab for the Treatment of Patients with Progressive Advanced Urothelial Carcinoma after Platinum-Containing Chemotherapy. Oncologist. 2017 Jun;22(6):743-49.

19. Rosenberg JE, Hoffman-Censits J, Powles T, van der Heijden MS, Balar AV, Necchi A, et al. Atezolizumab in patients with locally advanced and metastatic urothelial carcinoma who have progressed following treatment with platinum-based chemotherapy: a single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2016 May 7;387(10031):1909-20.

20. Xu C, Chen YP, Du XJ, Liu JQ, Huang CL, Chen L, et al. Comparative safety of immune checkpoint inhibitors in cancer: systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2018 Nov 8;363:k4226.

21. Peters S, Gettinger S, Johnson ML, Jänne PA, Garassino MC, Christoph D, et al. Phase II Trial of Atezolizumab As First-Line or Subsequent Therapy for Patients With Programmed Death-Ligand 1-Selected Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer (BIRCH). J Clin Oncol. 2017 Aug 20;35(24):2781-9.

22. Spigel DR, Chaft JE, Gettinger S, Chao BH, Dirix L, Schmid P, et al. FIR: Efficacy, Safety, and Biomarker Analysis of a Phase II Open-Label Study of Atezolizumab in PD-L1-Selected Patients With NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol. 2018 Nov;13(11):1733-42.

23. Mikami T, Liaw B, Asada M, Niimura T, Zamami Y, Green-LaRoche D, et al. Neuroimmunological adverse events associated with immune checkpoint inhibitor: a retrospective, pharmacovigilance study using FAERS database. J Neurooncol. 2021 Mar;152(1):135-44.

24. Johnson DB, Manouchehri A, Haugh AM, Quach HT, Balko JM, Lebrun-Vignes B, et al. Neurologic toxicity associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: a pharmacovigilance study. J Immunother Cancer. 2019 May 22;7(1):134.

25. Sato K, Mano T, Iwata A, Toda T. Neurological and related adverse events in immune checkpoint inhibitors: a pharmacovigilance study from the Japanese Adverse Drug Event Report database. J Neurooncol. 2019 Oct;145(1):1-9.

26. Chen G, Zhang C, Lan J, Lou Z, Zhang H, Zhao Y. Atezolizumab-associated encephalitis in metastatic breast cancer: A case report. Oncol Lett. 2022 Jul 27;24(3):324.

27. Salem Mahjoubi Y, Aouinti I, Charfi O, Zaiem A, Kaabi W, Lakhoua G, et al. Neurotoxicity following atezolizumab in a patient with tolerated rechallenge. Therapie. 2024 May-Jun;79(3):393-96.

28. Pedrero Prieto M, Gorriz Romero D, Gómez Roch E, Pérez Miralles FC, Casanova Estruch B. Neuromyelitis optica associated with the use of Atezolizumab in a patient with advanced lung adenocarcinoma. Neurol Sci. 2024 May;45(5):2199-202.

29. Prasertpan T, Teeyapun N, Bhidayasiri R, Sringean J. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor-Associated Striatal Encephalitis Presenting with Subacute Progressive Parkinsonism. Mov Disord Clin Pract. 2023 Aug 24;10(Suppl 3):S7-S11.

30. Chen CC, Tseng KH, Lai KL, Chiang CL. Atezolizumab-induced subacute cerebellar ataxia in a patient with extensive-stage small cell lung cancer. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2023 Aug 31;15:17588359231192398.

31. Kapagan T, Aksu F, Yuzkan S, Bulut N, Erdem GU. Atezolizumab-induced cerebellar ataxia in a patient with metastatic small cell lung cancer: A case report and literature review. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2024 Jan;30(1):201-5.

32. Ibrahim EY, Zhao WC, Mopuru H, Janowiecki C, Regelmann DJ. Hope, Cure, and Adverse Effects in Immunotherapy: Atezolizumab-Associated Encephalitis in Metastatic Small Cell Lung Cancer - A Case Report and Literature Review. Case Rep Neurol. 2022 Sep 20;14(3):366-71.

33. Evin C, Lassau N, Balleyguier C, Assi T, Ammari S. Posterior Reversible Encephalopathy Syndrome Following Chemotherapy and Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Combination in a Patient with Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022 Jun 2;12(6):1369.

34. Foulser PFG, Senthivel N, Downey K, Hart PE, McGrath SE. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome associated with use of Atezolizumab for the treatment of relapsed triple negative breast cancer. Cancer Treat Res Commun. 2022;31:100548.

35. Sebbag E, Psimaras, D.; Baloglu, S.; Bourgmayer, A.; Moinard-Butot, F.; Barthélémy, P.et al. Immune-Related Cerebellar Ataxia: A Rare Adverse Effect of Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. Off. J. Soc. NeuroImmune Pharmacol. 2022, 17 (3–4), 377-9.

36. Trontzas IP, Rapti VE, Syrigos NK, Kounadis G, Perlepe N, Kotteas EA, et al. Enteric plexus neuropathy associated with PD-L1 blockade in a patient with small-cell lung cancer. Immunotherapy. 2021 Sep;13(13):1085-92.

37. Esechie A, Fang X, Banerjee P, Rai P, Thottempudi N. A case report of longitudinal extensive transverse myelitis: immunotherapy related adverse effect vs. COVID-19 related immunization complications. Int J Neurosci. 2023 Dec;133(10):1120-3.

38. Lu BY, Isitan C, Mahajan A, Chiang V, Huttner A, Mitzner JR, et al. Intracranial Complications From Immune Checkpoint Therapy in a Patient With NSCLC and Multiple Sclerosis: Case Report. JTO Clin Res Rep. 2021 May 18;2(6):100183.

39. Nader R, Tannoury E, Rizk T, Ghanem H. Atezolizumab-induced encephalitis in a patient with metastatic breast cancer: a case report and review of neurological adverse events associated with checkpoint inhibitors. Autops Case Rep. 2021 Apr 15;11:e2021261.

40. Nishijima H, Suzuki C, Kon T, Nakamura T, Tanaka H, Sakamoto Y, et al. Bilateral Thalamic Lesions Associated With Atezolizumab-Induced Autoimmune Encephalitis. Neurology. 2021 Jan 19;96(3):126-7.

41. Wada S, Iwamoto K, Ozaki N. Atezolizumab, an immune checkpoint inhibitor, caused precedent depressive symptoms related to limbic encephalitis. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2022 Apr;76(4):125-6.

42. Özdirik B, Jost-Brinkmann F, Savic LJ, Mohr R, Tacke F, Ploner CJ, et al. Atezolizumab and bevacizumab-induced encephalitis in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: Case report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021 Jun 18;100(24):e26377.

43. Chang H, Shin YW, Keam B, Kim M, Im SA, Lee ST. HLA-B27 association of autoimmune encephalitis induced by PD-L1 inhibitor. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2020 Nov;7(11):2243-50.

44. Toyozawa R, Haratake N, Toyokawa G, Matsubara T, Takamori S, Miura N, et al. Atezolizumab-Induced Aseptic Meningitis in Patients with NSCLC. JTO Clin Res Rep. 2020 Feb 13;1(1):100012.

45. Ogawa K, Kaneda H, Kawamoto T, Tani Y, Izumi M, Matsumoto Y, et al. Early-onset meningitis associated with atezolizumab treatment for non-small cell lung cancer: case report and literature review. Invest New Drugs. 2020 Dec;38(6):1901-5.

46. Robert L, Langner-Lemercier S, Angibaud A, Sale A, Thepault F, Corre R, et al. Immune-related Encephalitis in Two Patients Treated With Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor. Clin Lung Cancer. 2020 Sep;21(5):e474-7.

47. Vogrig A, Muñiz-Castrillo S, Joubert B, Picard G, Rogemond V, Marchal C, et al. Central nervous system complications associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2020 Jul;91(7):772-8.

48. Francis JH, Jaben K, Santomasso BD, Canestraro J, Abramson DH, Chapman PB, et al. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor-Associated Optic Neuritis. Ophthalmology. 2020 Nov;127(11):1585-9.

49. Sengul Samanci N, Ozan T, Çelik E, Demirelli FH. Optic Neuritis Related to Atezolizumab Treatment in a Patient With Metastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. JCO Oncol Pract. 2020 Feb;16(2):96-8.

50. Thakolwiboon S, Karukote A, Wilms H. De Novo Myasthenia Gravis Induced by Atezolizumab in a Patient with Urothelial Carcinoma. Cureus. 2019 Jun 25;11(6):e5002.

51. Yuen C, Reid P, Zhang Z, Soliven B, Luke JJ, Rezania K. Facial Palsy Induced by Checkpoint Blockade: A Single Center Retrospective Study. J Immunother. 2019 Apr;42(3):94-6.

52. Kim A, Keam B, Cheun H, Lee ST, Gook HS, Han MK. Immune-Checkpoint-Inhibitor-Induced Severe Autoimmune Encephalitis Treated by Steroid and Intravenous Immunoglobulin. J Clin Neurol. 2019 Apr;15(2):259-61.

53. Garcia CR, Jayswal R, Adams V, Anthony LB, Villano JL. Multiple sclerosis outcomes after cancer immunotherapy. Clin Transl Oncol. 2019 Oct;21(10):1336-42.

54. Chae J, Peikert T. Myasthenia gravis crisis complicating anti-PD-L1 cancer immunotherapy. Crit. Care Med. 2018 Jan 1;46(1):280.

55. Tan YY, Rannikmäe K, Steele N. Case report: immune-mediated cerebellar ataxia secondary to anti-PD-L1 treatment for lung cancer. Int J Neurosci. 2019 Dec;129(12):1223-5.

56. Mori S, Kurimoto T, Ueda K, Enomoto H, Sakamoto M, Keshi Y, et al. Optic Neuritis Possibly Induced by Anti-PD-L1 Antibody Treatment in a Patient with Non-Small Cell Lung Carcinoma. Case Rep Ophthalmol. 2018 Jul 20 ;9(2) :348-56.

57. Laserna A, Tummala S, Patel N, El Hamouda DEM, Gutiérrez C. Atezolizumab-related encephalitis in the intensive care unit : Case report and review of the literature. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2018 Aug 2 ;6 :2050313X18792422.

58. Arakawa M, Yamazaki M, Toda Y, Saito R, Ozawa A, Kosaihira S, et al. Atezolizumab-induced encephalitis in metastatic lung cancer : a case report and literature review. eNeurologicalSci. 2018 Dec 17;14:49-50.

59. Marini A, Bernardini A, Gigli GL, Valente M, Muñiz-Castrillo S, Honnorat J, et al. Neurologic Adverse Events of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors : A Systematic Review. Neurology. 2021 Apr 20;96(16):754-66.

60. Astaras C, de Micheli R, Moura B, Hundsberger T, Hottinger AF. Neurological Adverse Events Associated with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: Diagnosis and Management. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2018 Feb 1;18(1):3.