Abstract

Injuries to the urinary tract are a frequent occurrence during gynecological procedures, particularly laparoscopic hysterectomy, with acute and chronic complications being reported. Urinary tract injuries occur in about 0.73% of laparoscopic hysterectomies, similar to abdominal hysterectomy rates. These injuries can lead to significant complications, including the formation of vesicovaginal (3.4%) and ureterovaginal (2.4%) fistulas, often requiring additional surgery. Bladder injuries are more prevalent than ureteral injuries. Bladder injury rates range from 0.5% to 0.66%, with Ureteral injuries ranging from 0.02%-0.4%. Thermal bladder injuries can occur due to the use of electrosurgery near the bladder. The spread of electrothermal injuries is greater than the initial area of blanching, creating a significant area of necrosis. Consequently, intraoperative detection of such injuries is challenging and the depth of injury is difficult to assess even if detected. This case report describes a 34-year-old woman who experienced a thermal bladder laceration during a laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy with sacrocolpopexy for a symptomatic grade II lateral cystocele, grade I uterine descensus and adenomyosis. Two weeks after the operation, the patient presented with bladder pain of varying intensity. After ruling out a urinary tract infection, a cystoscopy was performed which revealed a 1 cm thermal injury to the posterior wall of the bladder. Conservative treatment with NSAIDs was recommended as well as subsequent cystoscopy. At the 4-week follow-up, complete resolution was observed with no further evidence of injury. To our knowledge, there are no similar cases in the literature which were successfully treated without any surgical intervention. However, there are studies that recommend debridement prior to repairing all thermal bladder injuries, regardless of their size. This case highlights firstly the importance of caution when using electrosurgery and provides successful conservative management of iatrogenic thermal injury.

Keywords

Bladder injury, Cystoscopy, Laparoscopy, Sacrocolpopexy, Thermal injury

Introduction

The female reproductive and urinary tracts are closely related both embryologically and anatomically. Therefore, the possibility of bladder and ureter injury must be taken into account during gynecological surgery.

Evidence already demonstrates that the risk of urinary tract injury during gynecological surgery is high. Urinary tract injuries occur in approximately 0.73% of laparoscopic hysterectomies, a rate comparable to that of abdominal hysterectomies [1]. These rates may alter between studies. In other studies, it was demonstrated that the incidence of urinary tract injury is 0.3-1% in pelvic surgery, 0.33% in laparoscopic gynecological surgery, and 1.3% in laparoscopic hysterectomy [3-5]. Factors like the experience of the surgeon, the introduction of a new equipment or the complexity of the cases studied makes it difficult to assess the incidence rate of injuries. Bladder injuries are reported in 0.5% to 0.66% of cases, with most being identified during surgery. In contrast, ureteral injuries, which occur in 0.02% to 0.4% of procedures, are less frequently detected intraoperatively and may go unnoticed even with intraoperative cystoscopy. These injuries can have significant consequences, often necessitating additional surgical intervention. Moreover, the formation of vesicovaginal and ureterovaginal fistulas occurs in 3.4% and 2.4% of cases, respectively, following urinary tract injuries related to laparoscopic hysterectomy [1]. In particular, bladder injuries are more prevalent than ureteral injuries, and this risk is increased during laparoscopic hysterectomy [2]. Urinary tract injuries associated with gynecological surgery are classified into acute and chronic complications. Acute complications include ureteral ligation, ureteral and bladder lacerations. Chronic complications may occur days or weeks after surgery and include vesicovaginal fistula, ureterovaginal fistula and organ loss.

A number of factors have been identified as possible risk factors for bladder injury. In the field of obstetrics, risk factors for bladder injury during caesarean delivery include previous caesarean delivery, adhesions, emergent caesarean delivery, and caesarean delivery in the second stage of labor and/or after failed instrumentation. In both obstetrics and gynecology, risk factors include the presence of coexisting medical conditions that can lead to adhesions, such as endometriosis and Crohn's disease, and previous abdominal surgery, including caesarean delivery [6,7].

Bladder lesions can occur as a result of mechanical or thermal trauma. The estimated rate of electrosurgical complications related to the delivery of energy to the surgical site is 25.6% (70/273), making it the second most common laparoscopic complication after trocar or Veress needle misplacement at 41.8% (114/273) [8]. Surgical techniques are more difficult when the surgeon's spatial orientation and hand-eye coordination are not well established. Injuries during laparoscopic electrosurgery are similar to those during laparotomy and can be attributed to misidentification of anatomical structures, mechanical trauma or electrothermal injury [9]. The possible mechanisms of thermal injury are listed below:

Direct application of the electrosurgical probe, either by mistargeting or inadvertent activation. The dwell time determines the extent of tissue effect. Prolonged activation will produce wider and deeper tissue damage than the expected desired tissue effect.

A stray current resulting from poor insulation.

Direct coupling occurs when the active electrode is inadvertently activated or is in close proximity to another metal instrument.

Capacitive coupling occurs when electrical current is transferred from a conductor (the active electrode) through intact insulation to adjacent conductive materials (e.g. intestine) without direct contact.

Return electrode or alternative site burns. An alternative site burn can occur if the dispersive (ground) pad is not well attached to the patient's skin [10].

The greatest risk with thermal lesions is that the lesion may not be detected or well assessed intraoperatively. The main reason for this is that the spread of electrothermal injury is greater than the initial area of blanching, resulting in a large area of necrosis. This makes it difficult to assess the depth of the injury, even if it is noticed intraoperatively.

The European Association of Urology (EAU) classifies the bladder injuries according to the location of the injury: intraperitoneal, extraperitoneal and combined as well as the aetiology: non-iatrogenic (blunt and penetrating) and iatrogenic (external and internal). In contrast the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma injury classification of bladder injury is based on the size and site of the trauma (Table 1).

|

Bladder Injury Scale |

|||

|

Grade |

Injury Type |

Description of injury |

Management |

|

I |

Hematoma |

Contusion, intramural Hematoma |

Bladder injuries of grade 1 or 2 should be managed with prolonged drainage with indwelling urethral catheter for at least 7 to 14 days, and some studies recommend up to 3 weeks. Grade 1 and 2 injuries are not managed surgically |

|

II |

Laceration |

Extraperitoneal bladder wall laceration <2 cm |

|

|

III |

Laceration |

Extraperitoneal (≥ 2cm) or intraperitoneal (< 2cm) bladder wall laceration |

Bladder injuries of grade ≥ 3 require surgical management. Intraperitoneal injuries are generally more significant and involve higher risk of complications than extraperitoneal injuries.

|

|

IV |

Laceration |

Intraperitoneal bladder wall laceration ≥ 2 cm |

|

|

V |

Laceration |

Intraperitoneal or extraperitoneal bladder wall laceration extending into the bladder neck or ureteral orifice (trigone) |

|

These classifications also determine the therapeutic management. According to the latest EAU guidelines, perforations or lacerations should be closed intraoperatively, while the injuries not recognized during surgery should be managed according to their location. Conservative management consisting of clinical observation, continuous bladder drainage and antibiotic prophylaxis should be the standard of care for an uncomplicated extraperitoneal injury due to blunt or iatrogenic trauma [11]. Intraperitoneal injuries are generally more severe and carry a higher risk of complications than extraperitoneal injuries.

The above guideline does not cover thermal bladder injuries. The management of thermal lesions is more complicated. Surgical management is the main option for thermal injuries due to the risk of delayed necrosis or fistula formation. In the literature is widely recommended that thermal bladder injuries should be treated by debridement prior to repair, regardless of the size of the injury [12].

Case Presentation

A 34-year-old woman underwent laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy with sacrocolpopexy for symptomatic grade II lateral cystocele, grade I uterine descent, grade I rectocele and histologically confirmed adenomyosis. All possible conservative treatments for the uterine descensus and dysmenorrhea were either poorly tolerated or did not show significant improvement. Conservative treatments for uterine descensus involved physical therapies to improve pelvic floor muscle function through pelvic floor muscle training, local estrogen treatments, and mechanical methods like vaginal pessary insertion for prolapse support. For dysmenorrhea, conservative management included combined oral contraceptives, but these were poorly tolerated due to mood changes, and the patient declined the option of an intrauterine hormonal device (IUD). The indication for surgical treatment was therefore established. The patient had already undergone two previous laparoscopies for dysmenorrhoea. During the last two operations, an endometriosis (#ENZIAN P1, O 0/1, FA, rASRM I°) was also confirmed histologically. Despite previous surgery, there were relatively few adhesions and a standard supracervical hysterectomy was performed. The uterus, measuring 13x10x3.5 cm, was removed by morcellation. Sacrocolpopexy was performed with a standard TiLoop® mesh fixed with three caudal and two apical knots to the ventral and dorsal vagina and cervix respectively. There were no postoperative complications. The patient was discharged on the 3 postoperative day in good condition without any symptoms.

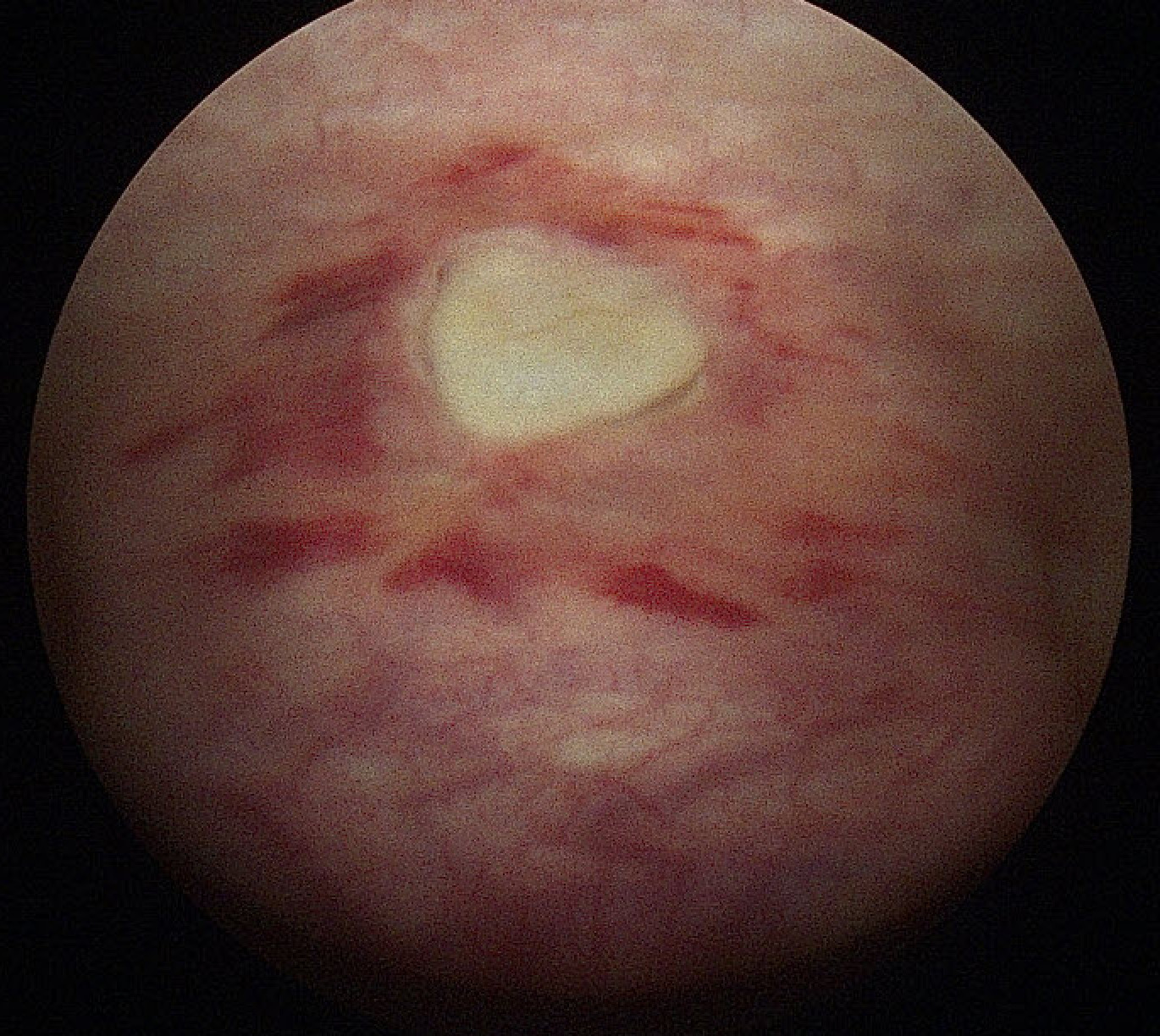

Approximately two weeks after the operation she presented at the emergency department with bladder pain of varying intensity over a period of 3 days. After ruling out urinary tract infection, and because of the severity of the symptoms a cystoscopy was performed to rule out bladder injury. Cystoscopy revealed a 1 cm thermal injury to the posterior bladder wall. This was considered consistent with cervicovesical dissection (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Thermal bladder injury sustained during cystoscopy on the 17th day postoperative.

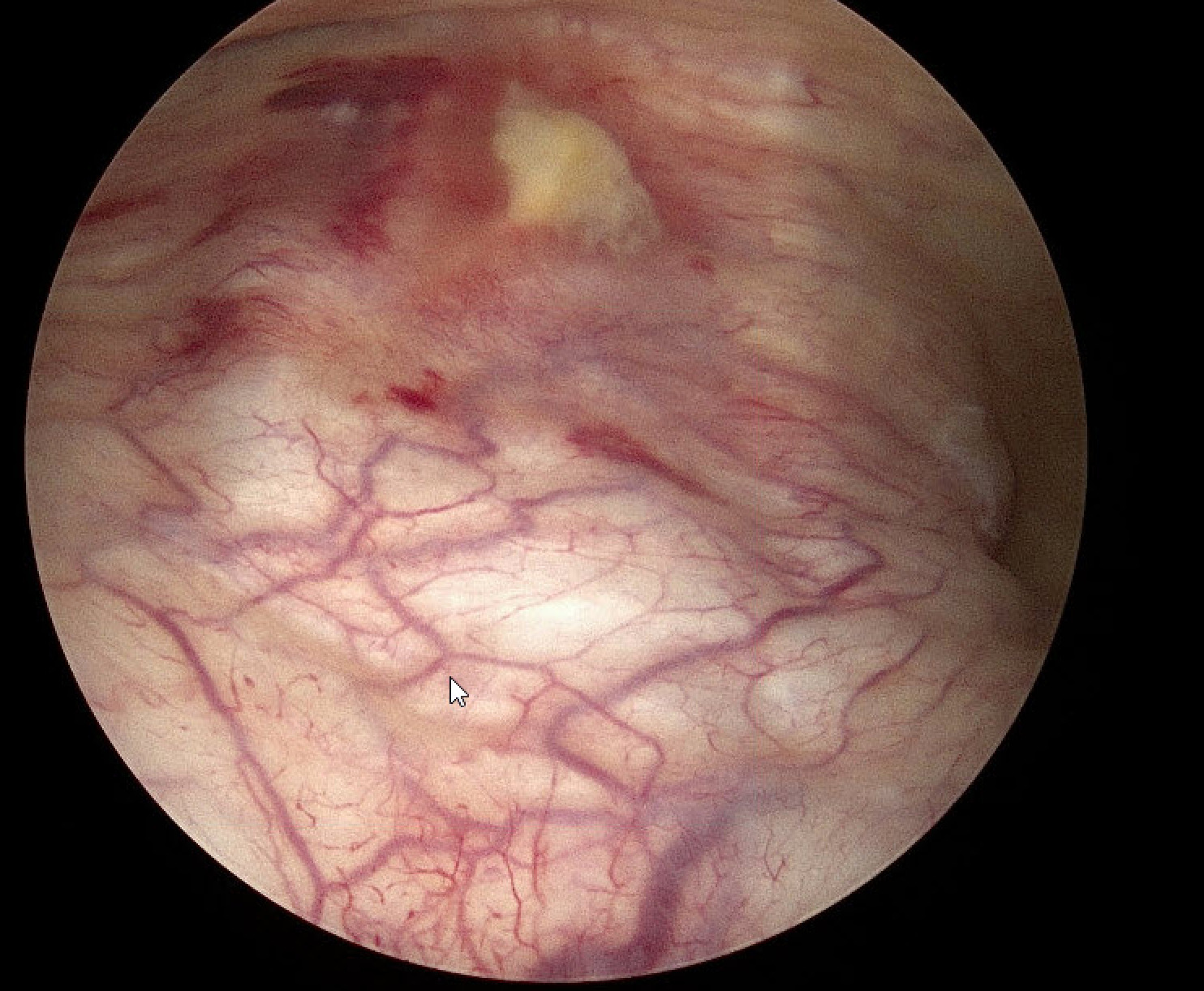

The patient was advised to follow a conservative management regimen, which involved the administration of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and subsequent cystoscopy at 2 and 4 weeks. The patient declined catheterization despite our strong recommendations. At the 2-week follow-up, the patient had no lower urinary tract symptoms and the cystoscopy revealed a substantial reduction in thermal injury (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The bladder injury is depicted following a period of two-week period of conservative treatment.

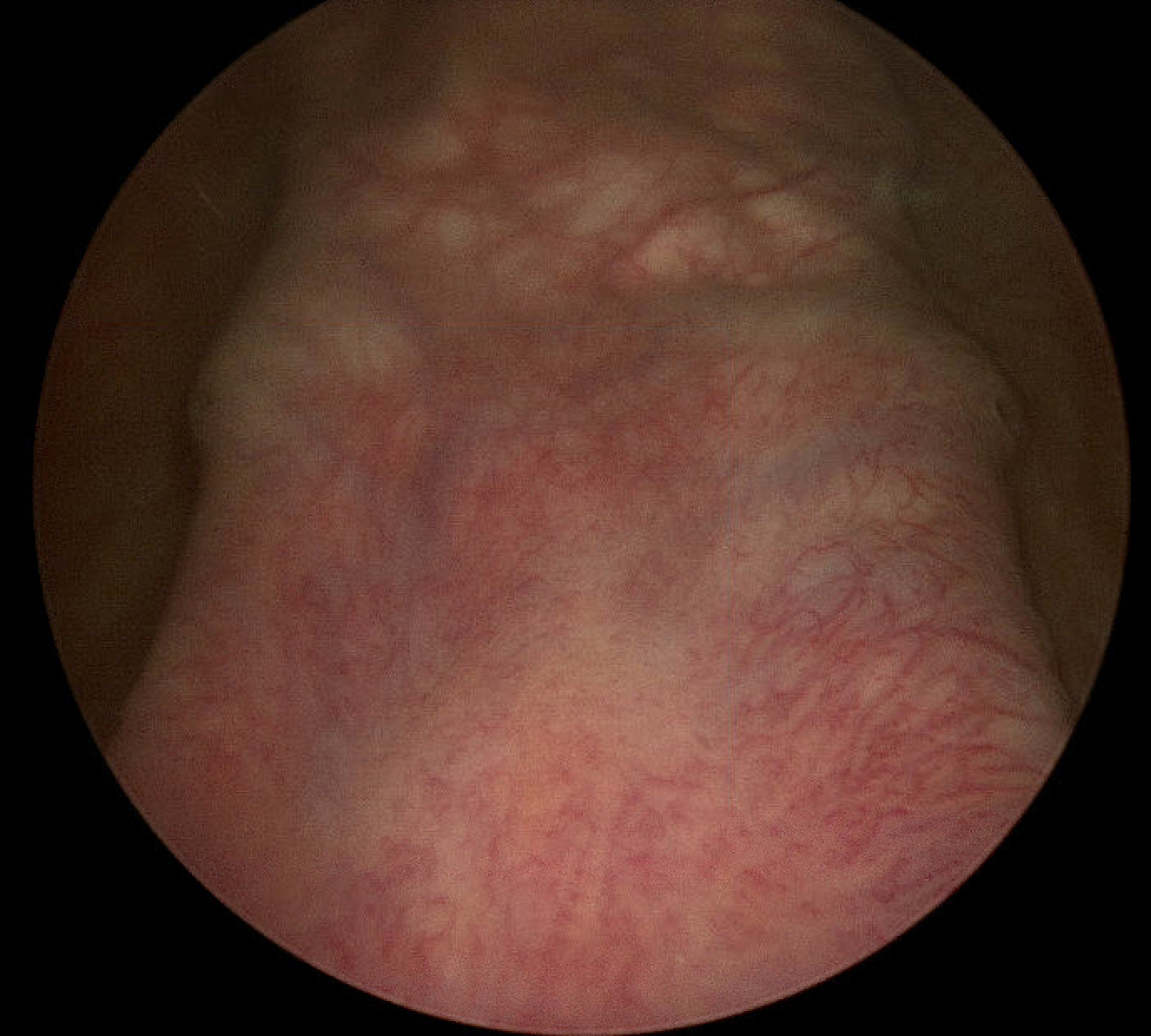

Following a period of four weeks, the injury had resolved completely, with no further evidence of injury observed (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Demonstrating complete resolution of the bladder injury after a period of 4 weeks.

Discussion

In this case report we present an alternative approach to the treatment of thermal bladder injuries. The management of a thermal bladder injury has been shown to present a significant challenge. The prevailing guidelines established by the American Urological Association (AUA) and the European Association of Urology (EAU) do not provide specific guidance on the management of thermal bladder injuries. Surgical interventions are the prevailing treatment option for thermal bladder injury, driven by the risk of delayed necrosis or fistula formation [13]. Minas et al. proposed a treatment strategy of debridement prior to repair for thermal bladder injuries, irrespective of the size of the injury. In contrast, an injury that pierces the bladder through the space of Retzius alone may be managed conservatively by means of an indwelling catheter for 2 weeks [12]. In this case report we present an alternative approach, employing a conservative treatment strategy, complemented by regular follow-up cystoscopies.

The use of an indwelling catheter for bladder decompression was a recommended that was strongly advocated but ultimately rejected by the patient. All studies agree on the use of an indwelling Foley catheter for bladder decompression, however, there is no consensus on the precise duration of bladder drainage. The duration of bladder drainage ranges from 1 to 3 weeks. A recent systematic review demonstrated that the length of transurethral catheterization ranged from 1 to 42 days.

No correlation was found between the duration of transurethral catheterization and the number

of complications [14].

The use of an indwelling catheter has been demonstrated to reduce the risk of bladder distension, enhance healing, reduce mechanical irritation to the injury site and mitigate the risk of urine extravasation into surrounding tissues, which could lead to serious complications like urinomas or fistula formation. In the presented case we hypothesize that the location of the injury was really the underlying reason behind the lack of additional complications, despite the absence of indwelling catheter use for bladder decompression. It is possible that the presence of the cervical stump may have served as an additional mechanical barrier and support (tamponade), thereby impeding the development of a vesicovaginal fistula.

The bladder laceration was identified through the utilization of a cystoscopy. The use of intraoperative cystoscopy for the diagnosis of bladder injury intraoperatively has also been subject of debate. The majority of studies demonstrate an absolute, but not statistically significant, increase in injury detection with routine cystoscopy after hysterectomy. The American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists has recommended that surgeons and institutions consider implementing, citing its cost-effectiveness and high detection rates [15]. However, the performance of a routine cystoscopy does not form part of our standard practice after hysterectomy. It is likely that in the future the ability of gynecologic surgeons to detect lower urinary tract injuries through cystoscopy will continue to improve and will contribute to the promotion of universal cystoscopy.

In this case report an iatrogenic thermal injury to the bladder was successfully managed by conservative therapy, obviating the need for surgical intervention. The conservative treatment of thermal bladder injuries is an option to be considered in cases where the extent and the location of the injury are taken into account. Intraperitoneal injuries are generally more significant and involve a higher risk of complications than extraperitoneal injuries. Injuries involving the trigone require additional attention. The objective of treatment should be to avoid obstruction of the ureters or the urethra.

The patient should be informed about the potential complications of a conservative treatment, such as uroperitoneum or vesico-genital fistula as well as mesh erosion in case of sacrocolpopexy. In these cases, surgical intervention will be necessary.

Research on bladder injury is challenging due to the limited number of patients treated at any given institution. Future research should continue to explore optimal treatment strategies, taking into account both clinical outcomes and patient preferences.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it is imperative to emphasize that urinary tract injuries are inevitable, even when performed by the most skilled medical professionals. Consequently, it is important to be familiar with strategies that reduce the occurrence of such complications and limit the resulting morbidity. It is vital for surgeons to possess a comprehensive understanding of the biophysics of electrosurgery, the characteristics of the equipment used, the desired tissue effects, the various types of injury, and the potential clinical manifestations. In addition to this, surgeons must, also master laparoscopic surgical dexterity with hand-eye coordination.

Funding

The authors declare no source of funding.

Conflict of interest statement

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

IRB Approval

The Institutional Review Board did not require ethical approval. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient to publish this paper.

References

2. Wong JMK, Bortoletto P, Tolentino J, Jung MJ, Milad MP. Urinary Tract Injury in Gynecologic Laparoscopy for Benign Indication: A Systematic Review. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jan;131(1):100-8.

3. Teeluckdharry B, Gilmour D, Flowerdew G. Urinary Tract Injury at Benign Gynecologic Surgery and the Role of Cystoscopy: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Dec;126(6):1161-9.

4. Blackwell RH, Kirshenbaum EJ, Shah AS, Kuo PC, Gupta GN, Turk TMT. Complications of Recognized and Unrecognized Iatrogenic Ureteral Injury at Time of Hysterectomy: A Population Based Analysis. J Urol. 2018 Jun;199(6):1540-5.

5. Lee JS, Choe JH, Lee HS, Seo JT. Urologic complications following obstetric and gynecologic surgery. Korean J Urol. 2012 Nov;53(11):795-9.

6. Tarney CM. Bladder Injury During Cesarean Delivery. Curr Womens Health Rev. 2013 May;9(2):70-6.

7. Ibrahim N, Spence AR, Czuzoj-Shulman N, Abenhaim HA. Incidence and risk factors of bladder injury during cesarean delivery: a cohort study. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2023 Feb;307(2):401-8.

8. van der Voort M, Heijnsdijk EA, Gouma DJ. Bowel injury as a complication of laparoscopy. Br J Surg. 2004 Oct;91(10):1253-8.

9. Hulka JF, Levy BS, Parker WH, Phillips JM. Laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy: American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists' 1995 membership survey. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1997 Feb;4(2):167-71.

10. Huang HY, Yen CF, Wu MP. Complications of electrosurgery in laparoscopy. Gynecology and Minimally Invasive Therapy. 2014 May 1;3(2):39-42.

11. Kitrey ND, Campos-Juanatey F, Hallscheidt P, Mayer E, Serafetinidis E, Sharma DM. EAU guidelines on urological trauma. EAU Guidelines Edn presented at the EAU Annual Congress Milan March 2023. 2023.

12. Minas V, Gul N, Aust T, Doyle M, Rowlands D. Urinary tract injuries in laparoscopic gynaecological surgery; prevention, recognition and management. Obstetrician & Gynaecologist. 2014 Jan 1;16(2):120-7.

13. Sharp HT, Adelman MR. Prevention, recognition, and management of urologic injuries during gynecologic surgery. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2016 Jun 1;127(6):1085-96.

14. Jensen AS, Heinemeier IIK, Schroll JB, Rudnicki M. Iatrogenic bladder injury following gynecologic and obstetric surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2023 Dec;102(12):1608-17.

15. AAGL Advancing Minimally Invasive Gynecology Worldwide. AAGL Practice Report: Practice guidelines for intraoperative cystoscopy in laparoscopic hysterectomy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2012 Jul-Aug;19(4):407-11.