Abstract

Introduction: This study compares the association between psychosis, suicide, and violent behavior in patients admitted and discharged from the psychiatric ward. Methods: This study used a cross-sectional design. The experimental study was done with all the psychotic patients fulfilling the inclusion criteria upon admission and discharge from a teaching hospital in Malaysia. The study was conducted for a duration of five months from March to July 2022. Psychotic patients with various diagnoses based on the DSM-5 were interviewed. PANSS score was used upon admission and discharge to look at the severity of psychosis. Suicide behavior was assessed using SBQ-R while violent behavior was assessed using MOAS. Sample size consist of 100 consecutive psychotic patients. Results: Suicide behavior was noted to be present in patients no matter the severity of psychosis. Upon discharge, even after the improvement of psychosis, patients were still at risk of suicide behavior. Violent behavior was noted to be present in most of the patients in the PANSS group (except for the moderately ill patients) no matter the severity of psychosis. However, upon discharge from the psychiatric ward, we can see that all patients went home not having violent behavior. This concludes that, when psychosis improves, the risk of having violent behavior reduces. Conclusions: Further exploration on the reasons of why suicide behavior persists in psychotic patients has to be done by clinicians. It is dangerous for clinicians to make assumptions that psychotic patients presenting with suicide behavior are solely due to the psychosis.

Keywords

Suicide behavior, Violent behavior, Psychotic patients, Aggressive behavior, Suicide intention

Introduction

Suicide is an important public health problem. Each year, about one million people die by suicide from across the world according to the World Health Organization [1,2]. More than 90% of victims of suicide have a psychiatric disorder according to studies done in America. Suicide attempts are commonly caused by mood and psychotic disorders [2-7]. Over the past 45 years, suicide rates have increased by 60% in Malaysia creating major concern [13]. In Malaysia, from the year 1999 to 2007, government hospital admissions for attempted suicides and deaths have increased. Malaysia also has a moderately high suicide rate which is approximately 12 per 100,000 [14].

Violence is defined in the Oxford Dictionary as “behavior involving physical force intended to hurt or kill.” Violence defines a wide range of behaviors from minor assaults, destructive acts, sexual assaults, assaults using a weapon and severe violence causing injury or death. Since the 19th century, it has been widely acknowledged that compared to healthy individuals, those with mental illness are more often involved in violent crimes. Up until now, the public still perceive the mentally ill to be at a heightened risk for engaging in violent acts [12].

Materials and Methods

This is a cross-sectional study and based in a hospital setting. History of the patients daily admitted to the psychiatric ward was analyzed. Among them, all those fulfilling inclusion criteria and who presented with psychotic symptoms were shortlisted. The individuals who consented to participate in the study were then interviewed. The interview and assessment were done twice, once upon admission and again upon discharge. All patients recruited in the study underwent Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) ratings to determine the severity of psychosis. Patients who were in the category of severely ill and extremely ill were excluded from the study. This was because those patients were uncooperative and difficult to be interviewed. The remaining patients that were cooperative for interview were assessed for suicide and violent behavior with the Suicide Behaviors Questionnaire - Revised (SBQ-R) and the Modified Overt Aggression Scale (MOAS), respectively. In total, 110 patients were recruited for the study.

Inclusion criteria

Patient’s age should be between 18-60. Patient is capable of understanding and answering questions in English or Malay. There are available means to contact the patient if needed. Patient gives consent to participate in this study. Patient who is experiencing psychotic symptoms and is admitted to the psychiatric ward.

Exclusion criteria

Patient does not give consent or withdraws their consent to participate in this study. Patient is unable to understand and answer questions in English or Malay. Unable to contact patient when needed. Patient who is below 18 years of age. Patient who is above 60 years of age. Patient who suffers from cognitive impairment. Patient who develops psychosis secondary to organic causes.

A pre-constructed questionnaire that was designed for the research was used to gather sociodemographic data. The PANSS rating scale was used to determine the severity of psychosis. In order to give a significant clinical meaning, Clinical Global Impressions (CGI) ratings were compared with PANSS total ratings after the results were obtained. The suicide behavior was measured using SBQ-R while the violent behavior was measured using MOAS. This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of UMMC (MEC 20211223-10862).

Measurement Tools

PANSS: The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) is a clinical instrument principally developed to identify the presence and severity of psychopathology symptoms. It is used for assessing positive, negative, and general psychopathology within the past one week. Of the 30 items, seven are positive symptoms, seven are negative symptoms and 16 are general psychopathology symptoms. Symptom severity for each item is rated according to which anchoring points in the 7-point scale (1 = absent; 7 = extreme) best describe the presentation of the symptom. The PANSS is an open scale available online.

SBQ-R: The Suicide Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised (SBQ-R) is a questionnaire designed to identify risk factors for suicide in adolescents and adults. The four-item questionnaire asks about four constructs within the suicide behavior domain: lifetime ideation and attempt, recent frequency of ideation, suicide threats, and likelihood of future suicide behavior. The four items are rated on Likert scales of varying lengths, resulting in total scores between 3 and 18. The SBQ-R is an open scale available online.

MOAS: The Modified Overt Aggression Scale (MOAS) is a widely used measure that has been validated for use in both children and adults. It was developed to assess four types of aggressive behavior: verbal aggression, aggression against property, auto aggression, and physical aggression. The MOAS rates the patient's violent behavior over the past week. Items are scored on a 5-point scale. Scores range from 0 to 40, with higher scores indicating more violence. Permission was obtained from ‘The Reach Institute 2022’ for its usage.

Statistical analyses

Data analysis was executed with SPSS, Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 21 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). All continuous variables in this study underwent a normality test. All continuous data that was distributed normally (had the reading of skewness between -1 and +1 and kurtosis between -3 and +3) were reported in mean and standard deviation. All continuous data that was not normally distributed, were reported as median and interquartile range (IQR). All categorical data were reported as a whole number and percentage. The sociodemographic statistics of the participants are presented both in categorical and continuous variables (age). The data collected from the participants were the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) to measure the severity of psychosis, the Suicide Behavior Questionnaire- Revised (SBQ-R) to measure the presence of suicide behavior and the Modified Overt Aggression Scale (MOAS) to measure violent behavior. The PANSS score was categorized according to the CGI severity of illness ratings for clinical significance.

Results

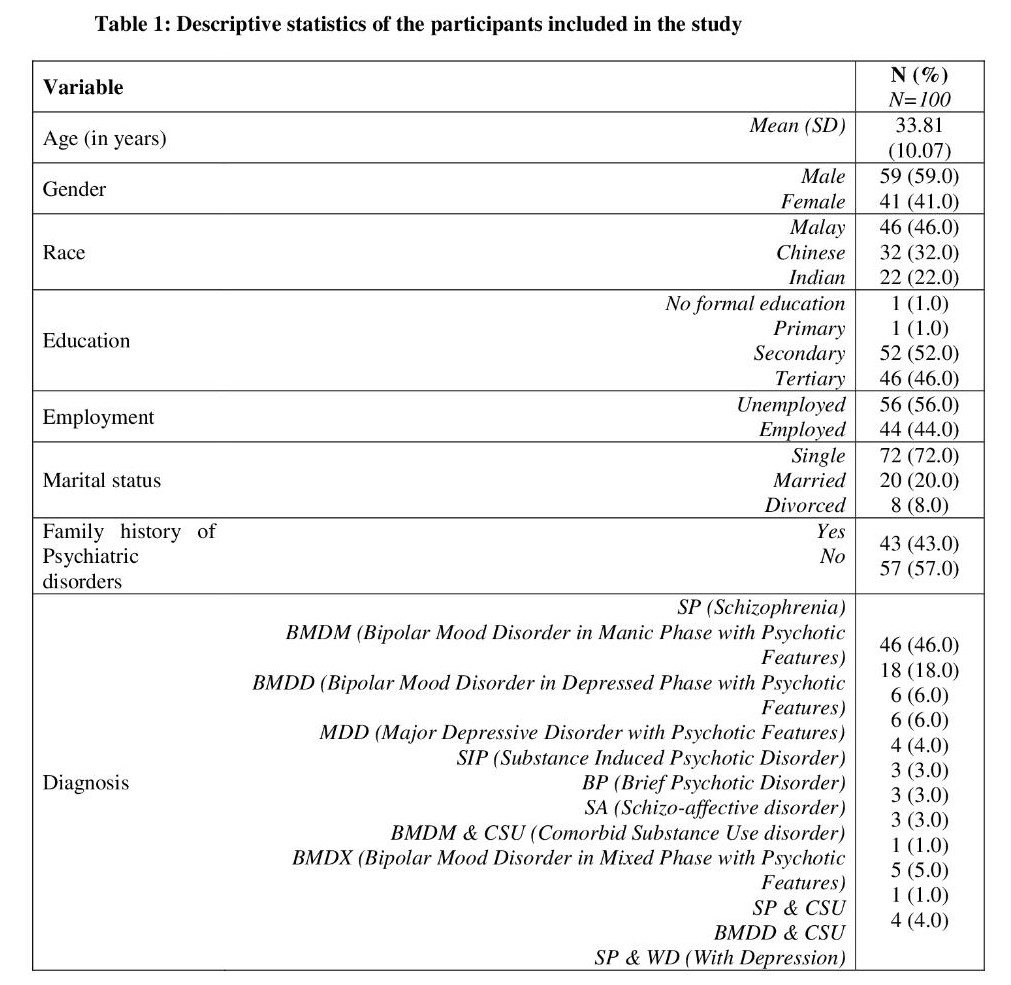

Table 1 describes all the descriptive statistics of the participants included in the study. The only continuous variable in the descriptive statistics was the age (in years). The mean age was 33.81 (SD: 10.07). From the total, 59% of the participants were male, 46% were of the Malay race, 52% had an education level of up to secondary education, 56% were unemployed, 72% were married, 57% had no family history of psychiatric disorders and 46% of them had a diagnosis of schizophrenia.

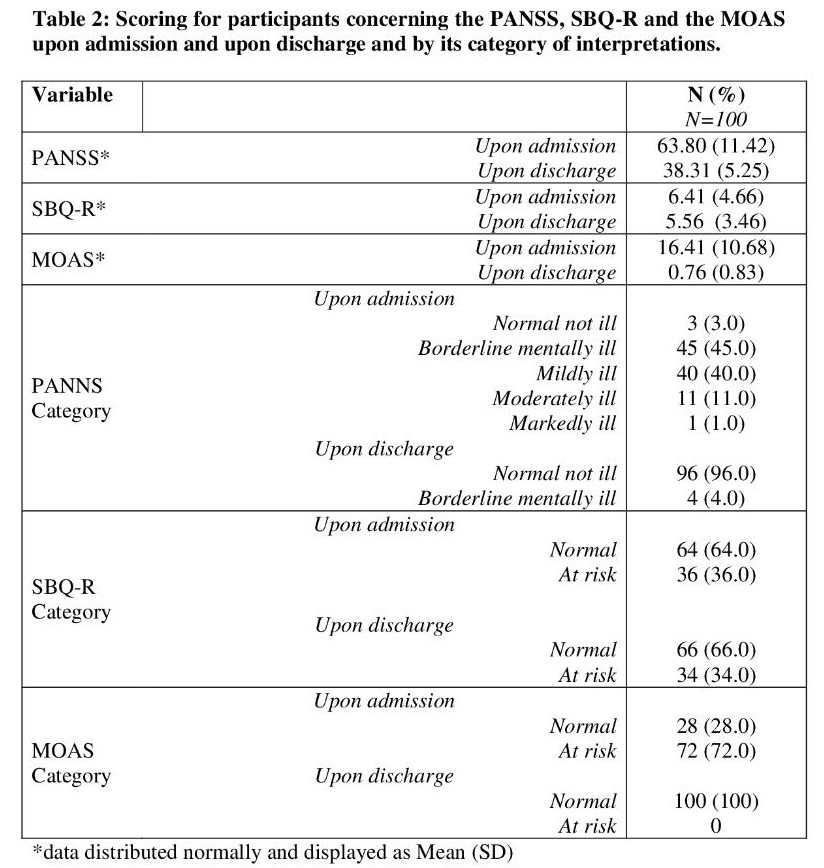

Table 2 shows the scoring of participants for the PANSS, SBQ-R, and the MOAS scores by mean (SD) and also by categories when measured upon admission and upon discharge. The mean (SD) PANSS, SBQ-R, and MOAS scores upon admission were 63.80 (11.42), 6.41 (4.66) and 16.41 (10.68) and the discharge scores were 38.31 (5.25), 5.56 (3.46), and 0.76 (0.83) accordingly. For the categories, 45% of the participants had a PANSS category of “borderline mentally ill” upon admission and 96% of them had a “normal not ill” upon discharge. For the SBQ-R category, 64% of the participants were not at risk of having suicide behavior upon admission and 66% of them were not at risk of having suicide behavior upon discharge. For the MOAS category, upon admission 72% of them were at risk of having violent behavior and all of them being “normal” upon discharge.

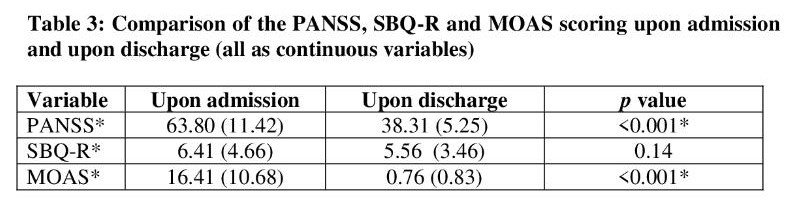

Table 3 is continuous scores comparisons of PANSS, SBQ-R and MOAS upon admission and upon discharge. Since the distribution of all scores were normally distributed and the nature of data collection was a before and after (upon admission and upon discharge), a dependent t-test was done to calculate if there was a statistically significant difference between the scores. There was a statistically significant difference in the scores of the PANSS and MOAS (both p<0.001) whilst there was no statistically significant difference between the SBQ-R scores (p=0.14).

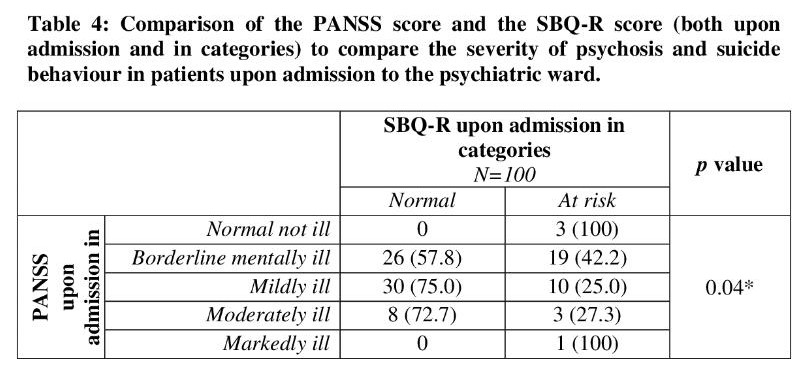

Table 4 shows the comparison between the PANSS score (measuring severity of psychosis) and SBQ-R score (measuring suicide behavior) for patients admitted to the psychiatric ward. A chi-square test was performed and it showed a statistically significant difference between the two scores (p=0.04). From the eye balling method, we can see that all patients who were normal upon admission were still at risk of suicide. Furthermore, 42.2% of those rated borderline mentally ill were at risk of suicide, 25% of the mildly ill rated group were at risk of suicide, 27.3% of the moderately ill rated group were at risk for suicide and 100% of those rated markedly ill were at risk of suicide.

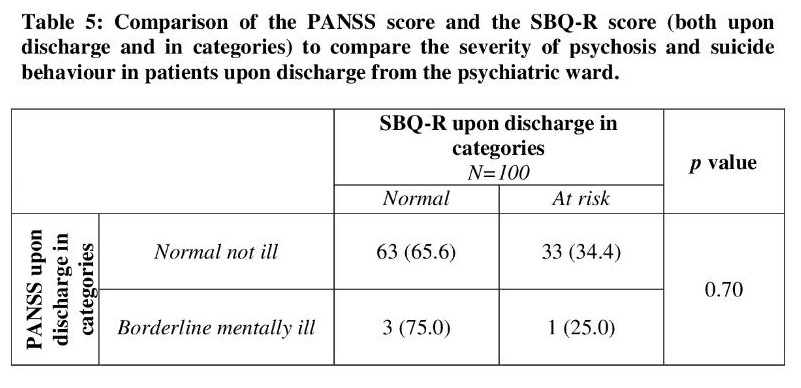

Table 5 shows the comparison of the PANSS score (measuring severity of psychosis) and SBQ-R score (measuring suicide behavior) upon discharge and in categories. A chi-square test was applied and it showed no statistically significant difference between the two. However, we can see a normalcy in patients and the risk of suicide reduced from 100% upon admission to 34.4% upon discharge. Meanwhile, those rated borderline mentally ill reduced from 42.2% upon admission to 25% upon discharge.

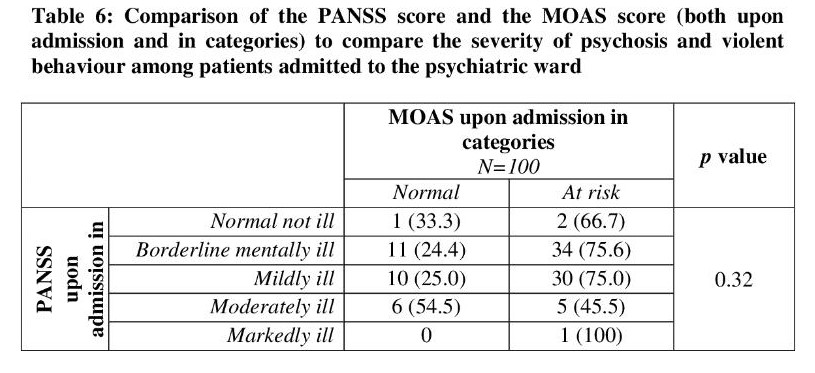

Table 6 shows the comparison between psychosis and violent behavior scores upon admission. A chi-square test was performed and it showed that there was no statistically significant difference (p=0.32) between the two assessments. Most of the patients in the PANSS group (except for the moderately ill) were at risk of being violent (range between 66.7%-100%). In the moderately ill rated group, 54.5% of them were more likely to be non-violent.

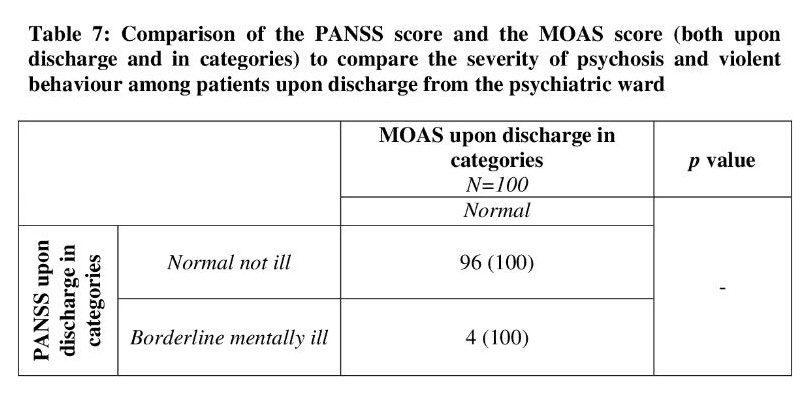

Table 7 shows the comparison between the PANSS score and MOAS score (both upon discharge and in categories) comparing the severity of psychosis and violent behavior upon discharge. We can see that all patients went home not having violent behavior. Moreover, 75.6% of those rated borderline mentally ill who were at risk upon admission also went back not having violent behavior.

Discussion

This study was done to see whether the severity of psychosis influenced a patient’s suicidal and/or violent behavior. In our daily clinical practice, a majority of the psychiatric patients are admitted to the ward due to suicide or violent risk. Thus, comparing the patient’s severity of psychosis with suicidal and violent behavior upon admission and discharge would determine whether there is an association between them. The PANSS total ratings were compared with CGI ratings to establish a clinical meaning. CGI rates illness severity based on a seven point scale. This rating is based upon observed and reported symptoms, behavior and function in the past 7 days. The score reflects the average severity level.

The majority of the patients admitted to the ward had a mean age of 33.81. From the total, 59% of the participants were male, 46% were of the Malay race, 52% had an education level of up to secondary education, 56% were unemployed, 72% were married, 57% had no family history of psychiatric disorders, and 46% of them had a diagnosis of schizophrenia (Table 1).

When measured in categories, upon admission based on PANSS score, 45% were rated as borderline mentally ill, 40% mildly ill, 11% moderately ill and 1% markedly ill. After receiving treatment, 96% went back home rated normal, without any symptoms, while 4% were still rated borderline mentally ill. The suicide behavior scale shows that 64% of psychotic patients were not at risk upon admission, such that 36% of patients were at risk upon admission. However, upon discharge, despite receiving treatment, 34% were still at risk. 28% of psychotic patients were not at risk of violent behavior upon admission, such that 72% of patients had violent behavior upon admission. Upon discharge, all the patients went back home rated as being without any violent behavior (Table 2).

When a dependent t-test was used to calculate the statistical significance between all the 3 scales as continuous variables, it was noted that there was a statistically significant difference in the scores of the PANSS and MOAS (both p<0.001) whilst there was no statistically significant difference between the SBQ-R scores (p=0.14). This could mean that treatment with psychiatric medication did not influence the SBQ-R scoring upon discharge compared to PANSS and MOAS (Table 3).

The association between psychosis and suicide behavior was compared in categories for patients admitted to the psychiatric ward. Patients admitted with a normal PANSS score had suicide behavior. Similarly, patients with markedly ill PANSS score were also at risk of suicide behavior (Table 4). Suicide behavior is present in patients no matter the severity of psychosis. Upon discharge, 34.4% of patients who were rated normal were still at risk of suicide behavior. Meanwhile, 25% with the borderline mentally ill rating were at risk of suicide behavior upon discharge (Table 5). This proves that despite the psychosis being treated, some patients still continue to experience suicide behavior even upon discharge.

The association between psychosis and violent behavior was compared in categories for patients admitted to the psychiatric ward. Most of the patients in the PANSS group (except for the moderately ill) were at risk of being violent upon admission. This shows that patients with psychosis regardless of their severity have risk of violent behavior and need to be treated (Table 6). Furthermore, we can see that all patients went home not having violent behavior upon discharge from the psychiatric ward (Table 7). This proves that with treatment of psychotic symptoms, patients are no longer at risk of having violent behavior.

Limitations

There are a number of limitations that needs to be acknowledged in this study. The cross sectional nature of this study prevents us from assessing the causality of the factor. Instead, we could only study their association. A convenient sampling was used to collect the samples from this population. The sample of patients selected were from those admitted to the university hospital. Having more participants from different hospitals would have given a clearer picture of the results. Moreover, suicidal ideation/thoughts are very subjective and it is only possible to assess from patients themselves by self-report. In contrast, violent behavior can be observed by others. Furthermore, the duration of hospital stay and the different types of treatment given during hospitalization might influence the study results. Furthermore, patients who were in the category of severely ill and extremely ill were excluded from the study, which limits the results to a less ill population.

Conclusions

To the best of my knowledge, this is the first study in Malaysia that assessed the association between psychosis, violent, and suicide behavior. It is to be noted that psychotic patients have more violent behavior compared to suicide behavior. The severity of the psychosis does not influence the suicide or violent behavior. Although violent behavior is higher compared to suicide behavior upon admission, the former reverts to normal after treatment of psychosis. Unfortunately, despite treatment of psychosis, some patients continue to have risk of suicide behavior upon discharge. Thus, further exploration on the reasons of suicide behavior in these patients have to be done by clinicians. It is dangerous for clinicians to make assumptions that psychotic patients presenting with suicide behavior are solely due to the psychosis. A lot more studies need to be done to better understand and manage suicide and violent behavior in Malaysia.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors of this manuscript declare no conflict of interest.

References

2. Hawton K, van Heeringen K. Suicide. Lancet. 2009;373;1372-1381.

3. Mann JJ. A Current Perspective of Suicide and Attempted Suicide. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2002;136(4):302.

4. Nordentoft M, Jeppesen P, Abel M, Kassow P, Petersen L, Thorup A, et al. OPUS study: Suicidal behaviour, suicidal ideation and hopelessness among patients with first-episode psychosis. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;181(S43):s98–s106.

5. Sher L, Oquendo MA, Mann JJ. Risk of suicide in mood disorders. Clinical Neuroscience Research. 2001;1(5):337-344.

6. Brådvik L. Suicide Risk and Mental Disorders. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2018;15(9):2028.

7. Caldwell CB, Gottesman II. Schizophrenics Kill Themselves Too: A Review of Risk Factors for Suicide. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1990;16(4):571-589.

8. Taylor PJ. Motives for offending among violent and psychotic men. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1985;147(5):491-498.

9. Link BG, Steue A. Psychotic symptoms and the violent/ illegal behavior of mental patients compared to community controls. In: Monahan J, Steadman H (eds). Violence and Mental Disorder. Chicago: University of Chicago Press: 1994; pp. 137-159.

10. Siris SG. Suicide and schizophrenia. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 2001;15(2):127-135.

11. Junginger J, McGuire L. Psychotic Motivation and the Paradox of Current Research on Serious Mental Illness and Rates of Violence. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2004;30(1):21-30.

12. Link BG, Phelan JC, Bresnahan M, Stueve A, Pescosolido BA. Public conceptions of mental illness: labels, causes, dangerousness, and social distance. American Journal of Public Health. 1999;89(9):1328-1333.

13. Malaysian Psychiatric Association. Suicide-It's SOS. 2007, http://www.psychiatry-malaysia.org/article.php?aid=504

14. Maniam T, Chan LF. Half a century of suicide studies' a plea for new directions in research and prevention. Sains Malaysiana. 2013;42(3):399-402.