Introduction

The traditional African diet is considered a very rich source of nutrition being largely whole with minimal processing [1]. There are unique challenges when managing Diabetes in Africa especially when making nutritional recommendations. An appropriate diet protects organ (heart, liver, pancreas etc.) health and vice versa. This is particularly true for chronic illnesses like diabetes mellitus [2]. Nutritional modifications are fundamental to and must be prioritized in the management of diabetes mellitus. Adherence to Medical nutrition therapy is closely linked to diabetes outcomes. In our recent publication, we shared recommendations for matching insulin use with common African cuisines (largely starchy carbohydrates) [3]. In this short commentary to our article [3], we examine the implications of the African cuisine for patients with diabetes mellitus. Strategies to promote favorable health outcomes via dietary modifications will also be discussed.

African Cuisines and Their Health Implications

Africa is known for its rich array of cuisines; making it the continent with highest number of food choices. Especially in Africa, food bears huge cultural significance [4]. Several food items have been described as having health promotion benefits, and in some instances used for therapeutic purposes [5]. Energy giving food substances like rice, cassava products (eg fufu and garri in Nigeria, kenkey in Ghana) are commonly consumed by persons with diabetes mellitus [5].

Often, the overblown advertisements on ‘’diabetic diet’’ for certain food substances like basmati rice is driven by monetary gains by desperate businessmen. It is commonplace to find lots of emphasis on the use of wheat, unripe plantain (in its varied forms), bean and bean - related products as components of cuisines of the African living with diabetes mellitus [6]. While it still remains difficult to satisfactorily describe the ‘’traditional African diet’’, we demonstrated in our recent article [3] that sub - Saharan Africa (SSA) ethnic cuisines contain starchy foods along with a sauce or soup. The starchy food is made from cereals, roots and tubers simply labeled as ‘CMT’ (cereals, millets, tubers) [7]. Sauce or soup dip consists of a vegetable platter or dish made from legumes, meat or fish [5].

Several health benefits are derived from the consumption of these staple African cuisines if the food preparatory methods are appropriate and attention is paid to portion size. Unfortunately, there is a growing nutritional transition in Africa whereby consumption of energy - dense and ultra - processed foods is in vogue. These foods are known to have high glycemic indices and because of the quantities consumed at a sitting they also have high glycemic loads. Thus, they are associated with post-prandial glucose spikes, high glycemic variability, postprandial hyperlipidemia and postprandial hyperglycemia. This meal pattern is ultimately detrimental to health, and has contributed to the rising burden of obesity and cardiovascular diseases. [8] Westernization with its attendant sedentary predisposition expose individuals to ready - to - eat (‘fast’) foods and commercially available snacks, which are generally refined, energy dense and high in fat content [9].

The excessive use of saturated fats with the erroneous belief that they are healthy is commonly seen in African cities and rural communities. Plant based fats and oils with a high content of saturated fats like palm oil and coconut oil are exaggerated for their ‘’medicinal purposes’’ [10]. Excessive use of these plant sources of high saturated fats have in part contributed to the dwindling cardiovascular health of Africans living with diabetes mellitus. A deliberate education on dietary modifications is therefore a compelling need to improve diabetes outcomes for Africans consuming the African cuisine.

Strategies for Health Promotion Using the African Cuisine

How do we promote health / prevent chronic diseases like diabetes through diet? To provide answers to this very important question, we must carefully analyze dietary strategies that can be helpful. Some of these strategies include (but are not limited to);

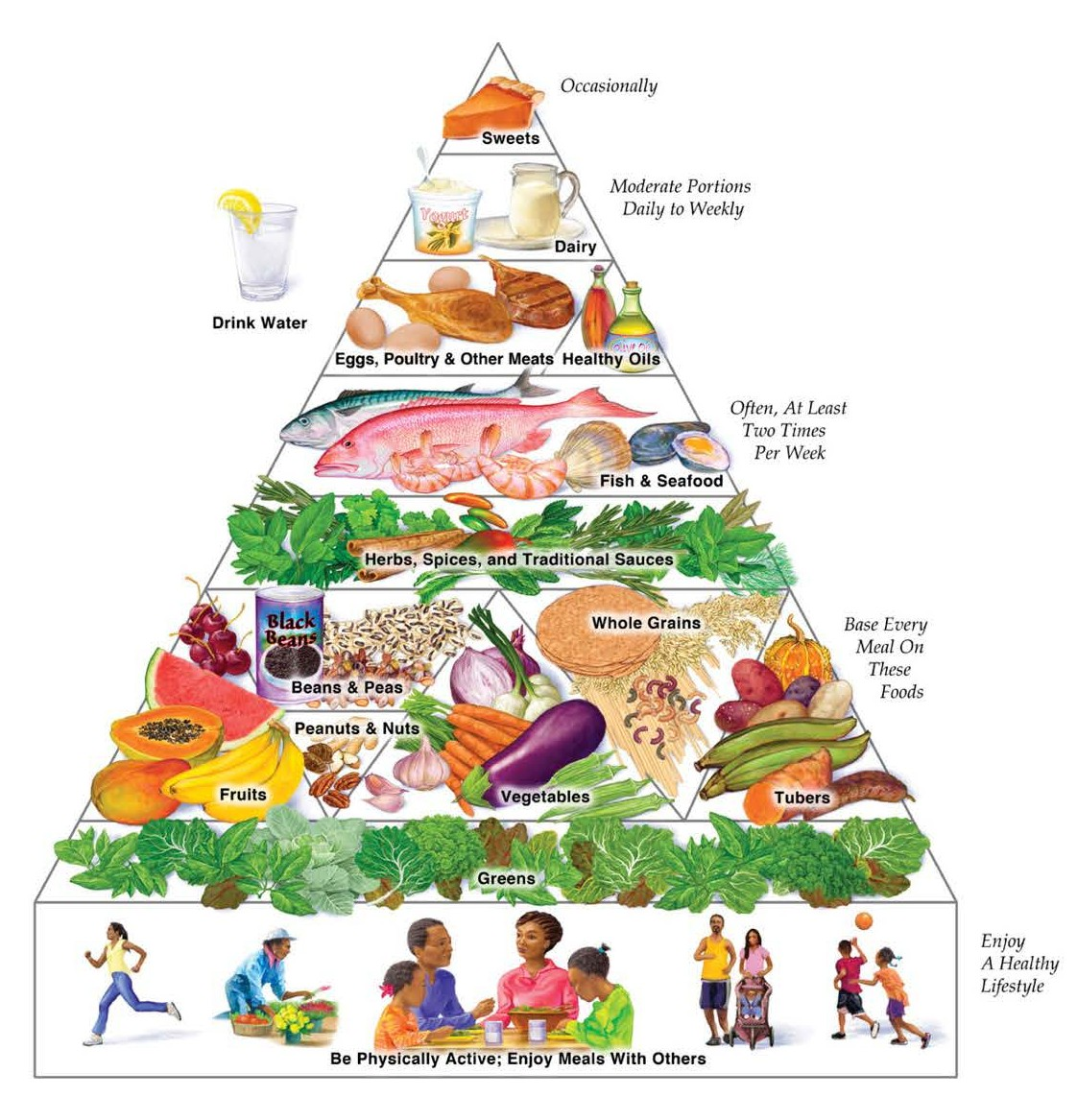

• Dietary education as an essential tool - this is important to all healthcare providers at all levels as well as to individuals living with or at risk of developing diabetes mellitus. Since the diet of the patient with diabetes is often considered as healthy diet [11], it follows that even the individuals who do not have diabetes should be encouraged to eat the same meal types and patterns as the patient with diabetes [11]. Every contact with the individual living with diabetes should be considered as a teachable moment with sharing of ideas on practical steps towards healthy eating. A strategy to promote healthy eating should involve the use of educational materials representative of healthy African ethnic cuisine. For instance, an African Heritage Diet Pyramid [12] containing the traditional African cuisine can be used as cultural models of healthy eating. The morning health talks that usually take place at our diabetes clinics should be designed to give simple practicable guides on diet which are acceptable to and feasible for patients. Contact with the patient during consultation should accord the opportunity for further emphasis on appropriate meal patterns. There is evidence to show that persons who receive adequate dietary education fare better in terms of overall outcomes in the management of diabetes [13].

• Patronage of home grown staple African food substances - a myth surrounding diet in people with diabetes is the belief that only expensive (most often imported) food items are suitable for patients with diabetes. The African diet even though composed of large amounts of starch, is still remarkable for its high fiber content and reasonably low glycemic index. [14] If appropriate portion sizes are consumed, these food substances have tremendous health benefits. African governments should provide incentives to farmers who grow the food crops that are typical of the traditional African diet.

Figure 1. African Heritage Diet Pyramid. Source: Reference number 12.

• Introduction of diet and health concept into the academic curricula of schools - it is common knowledge that the healthcare providers need basic education on nutritional therapy for management of diabetes. Introduction of dietary education and health at all levels of our educational system will go a long way in developing the consciousness of the average African towards healthy meal patterns. This may have far reaching beneficial outcomes in curtailing the growing epidemic of diabetes and cardiovascular diseases.

• Compulsory diet tax on unhealthy processed foods (if not outright ban) in Africa - there should be a disincentive for engaging in importation and use of highly processed foods. Higher taxes on the energy dense foods will discourage patronage thereby reducing the chances of developing diseases like type 2 diabetes and other obesity related conditions.

• Development and implementation of standard dietary guidelines in the management of diabetes - it is desirable that professional associations develop guidelines for nutritional modification of the African cuisine. These guidelines should be simple, easy to apply and acceptable to Africans without placing additional financial burden on families. Health institutions should be encouraged to adopt and implement these guidelines. A periodic audit of the application and outcomes of these guidelines should be undertaken.

• Appropriate medications matched with the African cuisines - the choice of medications for the management of diabetes should take into account the dietary habits of the individual. One good example is the initiative in our recent publication on African cuisine centered insulin therapy in Africa. More collaborative research is desired in this area across Africa.

Conclusion

The management of diabetes mellitus is incomplete without appropriate dietary guidance. Healthy eating promotes the overall health of the African living with diabetes. Dietary education and strategies to encourage a healthy African cuisine should be advocated at all stages in the management of individuals with diabetes mellitus. More collaborative work among African scholars in the field of diabetes is required.

Conflict of Interest(S)

None to declare.

References

2. Kelly SA, Hartley L, Loveman E, Colquitt JL, Jones HM, Al-Khudairy L, et al. Whole grain cereals for the primary or secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017(8).

3. Mbanya JC, Lamptey R, Uloko AE, Ankotche A, Moleele G, Mohamed GA, et al. African Cuisine-Centered Insulin Therapy: Expert Opinion on the Management of Hyperglycaemia in Adult Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Therapy. 2020 Nov 9:1-8.

4. George TT, Obilana AO, Oyeyinka SA. The prospects of African yam bean: past and future importance. Heliyon. 2020 Nov 1;6(11):e05458.

5. Oniang’o RK, Mutuku JM, Malaba SJ. Contemporary African food habits and their nutritional and health implications. Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2003 Sep 1;12(3). 331-336.

6. Lamptey R, Velayoudom FL, Kake A, Uloko AE, Rhedoor AJ, Kibirige D, et al. Plantains: gluco-friendly usage. JPMA. The Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association. 2019 Oct;69(10):1565-7.

7. Augustin LS, Kendall CW, Jenkins DJ, Willett WC, Astrup A, Barclay AW, et al. Glycemic index, glycemic load and glycemic response: An International Scientific Consensus Summit from the International Carbohydrate Quality Consortium (ICQC). Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases. 2015 Sep 1;25(9):795-815.

8. Bosu WK. An overview of the nutrition transition in West Africa: implications for non-communicable diseases. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 2015 Nov;74(4):466- 77.

9. Bourne LT, Lambert EV, Steyn K. Where does the black population of South Africa stand on the nutrition transition?. Public Health Nutrition. 2002 Feb;5(1a):157-62.

10. Boateng L, Ansong R, Owusu W, Steiner-Asiedu M. Coconut oil and palm oil’s role in nutrition, health and national development: A review. Ghana Medical Journal. 2016 Oct 12;50(3):189-96.

11. Marshall S, Petocz P, Duve E, Abbott K, Cassettari T, Blumfield M, Fayet-Moore F. The Effect of Replacing Refined Grains with Whole Grains on Cardiovascular Risk Factors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials with GRADE Clinical Recommendation. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 2020 Sep 12.

12. https://oldwayspt.org/resources/oldways-africanheritage- pyramid. Accessed on 22 April, 2021

13. Uloko AE, Ofoegbu EN, Chinenye S, Fasanmade OA, Fasanmade AA, Ogbera AO, et al. Profile of Nigerians with diabetes mellitus – Diabcare Nigeria study group (2008): Results of a multicenter study. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16(4):558-564. ERRATUM IN: Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012 Nov-Dec;16(6):981.

14. Omoregie ES, Osagie AU. Glycemic indices and glycemic load of some Nigerian foods. Pakistan Journal of Nutrition. 2008;7(5):710-6.