Abstract

Background: Despite established guidelines recommending routine HIV screening for individuals aged 13 to 64 at least once in their lifetime, testing remains underutilized in many primary care settings. Puerto Rico faces a disproportionately high HIV burden, particularly in the southern region, yet limited data exist on screening adherence and patient awareness. This study aimed to evaluate the socio-demographic characteristics and sexual behaviors associated with routine HIV testing among adults in primary care clinics in southern Puerto Rico.

Methods: An IRB-approved, retrospective cross-sectional study was conducted using a 20-item anonymous survey administered via REDCap. Participants (n=469) were adults aged 18 and older who accessed outpatient primary care services in southern Puerto Rico. The survey assessed HIV testing history, physician-patient communication, sexual behavior, and awareness of CDC guidelines.

Results: A concerningly high proportion of participants (66.9%) indicated that their primary care physician had not educated them about HIV testing, and 82.7% reported never having been asked or referred for an HIV test. HIV testing was nearly evenly distributed (49.7% tested vs. 48.9% untested). The most cited reason for not being tested was a perceived lack of necessity (73.4%). Participants who had been tested (mean age: 56.32 years) and those willing to accept testing (mean age: 58.87 years) were significantly younger than their counterparts (p<0.001). Sexual activity in the past year was strongly associated with prior HIV testing (p=0.005) and willingness to be tested (p=0.002). Awareness of CDC screening guidelines (45.4%) and the availability of free testing centers (40.1%) was low.

Conclusion: Findings underscore the need to improve physician engagement and HIV education in primary care. Age, sexual activity, and perceived need significantly influenced testing behaviors. Interventions targeting older adults and enhancing routine screening practices are critical to reducing HIV burden in Puerto Rico.

Keywords

HIV screening, Routine HIV testing, HIV prevention, CDC guidelines, Health education, Patient awareness, Sexual behavior, Puerto Rico

Introduction

The Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) continues to be a major public health challenge worldwide, with over 38 million people living with HIV as of 2022 [1]. HIV is a chronic illness caused by a retrovirus of the Lentivirus genus [2]. Early diagnosis and timely management are critical for improving health outcomes and preventing progression to a more severe version of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Approximately 40% of new HIV infections are transmitted by those who are unaware they carry the virus, and 15% of individuals who are HIV positive in the United States are unaware of their HIV status [3]. Despite significant advancements in antiretroviral therapy (ART) and public health campaigns aimed at reducing stigma, barriers to routine HIV testing persist, particularly in primary care settings. Routine HIV screening in primary care settings has been widely recommended by health authorities, including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the World Health Organization (WHO), whereas guidelines state that everyone between the ages 13 to 64 should be tested for HIV at least once in their lifetime [4]. To further encourage uptake, the CDC endorses an opt-out testing approach, in which HIV screening is performed routinely unless the patient declines. Studies have shown that this strategy aims to normalize HIV testing, reduce stigma, and increase the identification of undiagnosed cases [5]. However, implementation of these recommendations in outpatient clinics remains suboptimal and is often poorly documented. One of the primary challenges in achieving widespread implementation of routine HIV screening in outpatient clinics is the lack of patient education and physician adherence to screening guidelines. Most studies in outpatient clinics have stated that the general population agree they lack HIV awareness, indicating a necessity of general education and public health interventions [6]. This gap highlights the need to assess the barriers and facilitators of routine HIV screening and integrate targeted education initiatives to enhance patient understanding and acceptance.

Many patients are unaware of the significance of early HIV detection, the availability of effective treatments, or the public health benefits of knowing their HIV status. In outpatient settings, where patients often seek care for acute conditions rather than preventive services, HIV testing is rarely prioritized. Furthermore, misconceptions about HIV, fear of stigma, and limited knowledge about testing procedures further discourage patients from opting for HIV screening. According to local health statistics, in 2022 Puerto Rico had an estimated rate of new HIV infections among 13+ of 7.3 per 100,000 [7]. Puerto Rico also has a higher prevalence of HIV compared to many U.S. states, with the southern region disproportionately affected [8]. Yet, routine HIV screening is not consistently integrated into primary care assessments, leaving a significant portion of the population undiagnosed and at risk for complications. Education plays a pivotal role in transforming patient perceptions and behaviors regarding HIV testing. Patients who understand the benefits of early detection are more likely to consent to routine screenings [9]. By incorporating HIV education into routine healthcare visits, primary care providers can create opportunities to engage patients in meaningful conversations about their health and well-being.

Given the persistent underutilization of routine HIV screening in Puerto Rico and the documented disparities in HIV prevalence across regions, this study aims to assess whether primary care services in Puerto Rico adhere to CDC guidelines by routinely offering HIV screening to individuals between the ages of 13 and 64. Additionally, we seek to evaluate participants’ awareness and perceptions of HIV-related topics. The findings may help identify areas for improvement in current protocols and contribute to enhancing the quality of services provided by primary care facilities, ultimately supporting better health outcomes for individuals at risk of or living with HIV.

Methods

This study employed an IRB approved retrospective design to assess whether primary care services in Puerto Rico adhere to CDC guidelines for routine HIV screening. Data were collected using a 20-item anonymous survey administered via REDCap—an HIPAA compliant database—from June 2023 to January 2025 in three different outpatient clinics consisting of a total of five internal medicine specialists. Participants accessed the survey by scanning a QR code distributed by researchers at participating outpatient clinics.

Prior to survey completion, all participants provided informed consent, obtained by internal medicine specialists in accordance with HIPAA privacy regulations and IRB Committee approval. Participation was entirely voluntary, and individuals were not required to provide any data that could be used to identify them. Inclusion criteria required participants to be aged 18 and older who live in Puerto Rico with access to specific primary care outpatient clinics. The survey gathered data on demographic characteristics, healthcare access, history of HIV screening, and awareness of CDC screening recommendations.

Data analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS statistical analysis program, with a focus on identifying trends in HIV screening practices, patient-provider communication regarding HIV testing, and barriers to routine screening. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the characteristics of the study population and responses to each survey question. Additionally, Chi-square and Fisher analyses were employed to investigate relationships between variables and characterize patterns and associations within the dataset. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05 for all tests. IRB protocol number: protocol number 2304144544.

Results

A total of 507 participants were recruited for the study, 38 were excluded due to incomplete responses and 469 completed the questionnaire in full. The mean age of the population was 60.21 with a median of 65 and mode of 68. The gender distribution was predominantly female (62.9%, n=296), followed by male (36.2%, n=170), with a small proportion identifying as transgender (0.4%, n=2) or not providing a response (0.2%, n=1). Regarding sexual orientation (n=469), the majority identified as heterosexual (91%, n=428), while 2% (n=8) identified as homosexual and 1% (n=5) as bisexual. A total of 6% (n=28) did not disclose their sexual orientation. Among the 469 respondents, 53.7% reported being sexually active within the past year. A small proportion, 3.8% reported having multiple sexual partners, while 13.4% engaged in same-sex sexual activity.

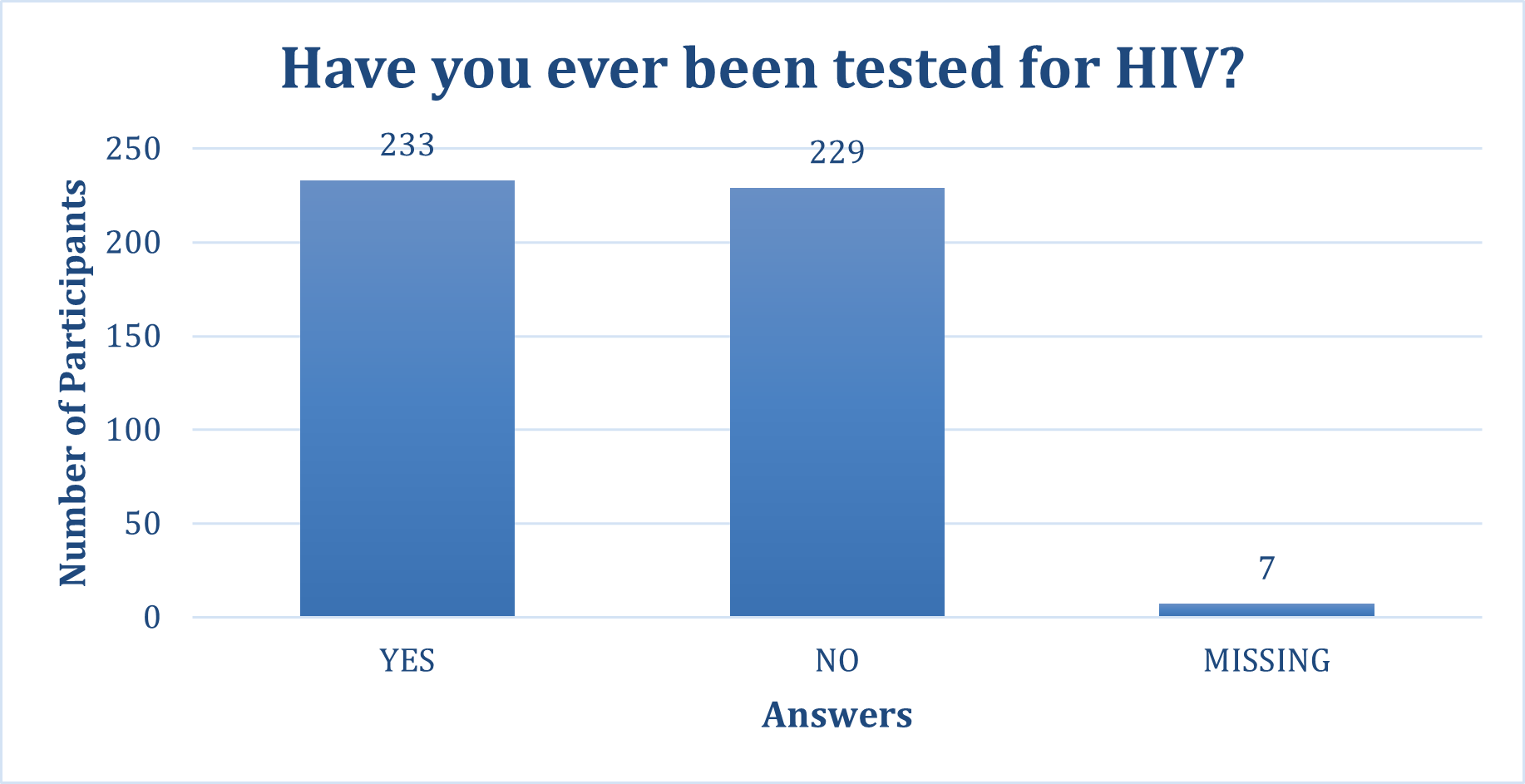

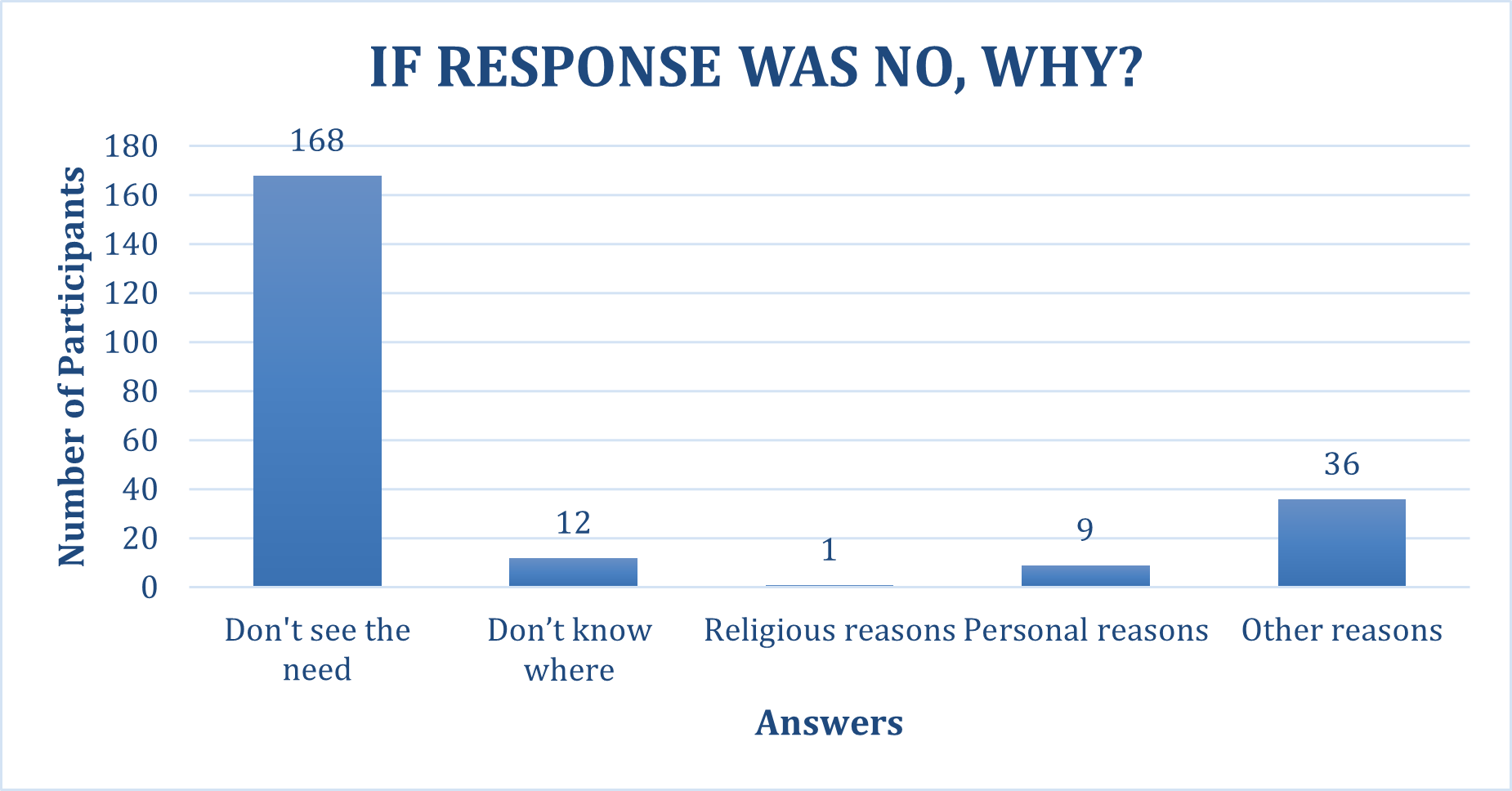

HIV testing history among participants was nearly evenly distributed, with 49.7% (n=233) reporting ever being tested for HIV and 48.9% (n=229) reporting never having been tested (Figure 1). A small proportion (n=7) had missing responses. Among those who had never been tested, the most cited reason was a perceived lack of need or importance (73.4%, n=168), followed by not knowing where to get tested (n=12), religious reasons (n=1), personal reasons (n=9), and other miscellaneous reasons (n=36) (Figure 2). Among participants who had been tested, the most common frequency was "once in my life" (40.3%, n=94), followed by "annually" (19.7%, n=46). Smaller percentages reported testing every three months (n=2), every six months (n=5), or within the past year (36%, n=84).

Figure 1. Participants responses to the question: “Have you ever been tested for HIV”? (n=469).

Figure 2. Reasons given by participants who reported never having been tested for HIV (n=229).

Regarding HIV testing awareness, 66.9% of the 469 participants indicated that their primary care physician had not educated them about HIV testing, and 82.7% had never been asked or referred to for an HIV test. Despite this, 78.7% (n=369) of respondents stated they would accept an HIV test if offered. Awareness of HIV testing guidelines and available resources was limited. A slight majority (54.6%) of the 469 participants were unaware of the CDC's recommendation for routine HIV testing for individuals aged 13 to 64, while 45.4% were aware. Additionally, 58.6% of respondents were unaware of the availability of free HIV testing centers, whereas 40.1% were informed about these resources. A small percentage (1.3%) did not provide a response (Table 1).

|

Questions regarding Primary Care Physician & knowledge: |

Response |

|

|

Yes |

No |

|

|

Have they educated you in HIV screening? |

155 |

314 |

|

Have they sent/asked for HIV tests? |

81 |

388 |

|

If offered, would you accept? |

369 |

100 |

|

Did you know about CDC recommendations about HIV screening ages? |

213 |

256 |

|

Did you know of HIV centers who offer tests free? |

188 |

275 |

Association between age and HIV testing behaviors

Results indicated that individuals who were sexually active in the past year were significantly younger (55.05 years) than those who were not (66.17 years; p<0.001). Similarly, individuals who had been tested for HIV were younger (56.32 years) than those who had not (64.08 years; p<0.001). Although younger individuals were slightly more likely to have received HIV education from their physician (56.90 years vs. 61.84 years) or to have been referred for testing (54.36 years vs. 61.43 years), these differences were not statistically significant. However, younger participants were significantly more likely to accept an HIV test if offered (58.87 years) compared to those who would decline (65.14 years; p<0.001) (Table 2).

|

Survey Questions |

Age Mean |

||

|

Yes |

No |

p-value |

|

|

Sexually active during the year |

55.05 (n=252) |

66.17 (n=215) |

<0.001 |

|

Have you ever done a HIV Test? |

56.32 (n=233) |

64.08 (n=229) |

<0.001 |

|

Has your primary physician ever educated you on HIV? |

56.90 (n=155) |

61.84 (n=314) |

0.101 |

|

Has your primary physician ever sent/asked for HIV testing? |

54.36 (n=81) |

61.43 (n=388) |

0.314 |

|

If your primary physician offered a test, would you accept? |

58.87 (n=369) |

65.14 (n=100) |

<0.001 |

Gender differences in HIV testing practices

A Chi-squared test assessed the relationship between gender and HIV testing behaviors. The proportions of men (n=171) and women (n=296) who had been tested were similar, with more women (n=150, 50.7%) than men (n=81, 47.4%) having undergone testing. The most common reason for not being tested was "I don’t see the need" (35.8%, n=168), followed by "Don’t know where to get tested" (51.8%, n=243). Men were slightly more likely to report a lack of perceived need (n=66), while women more frequently cited lack of knowledge on where to get tested (n=154), though these differences were not statistically significant (p=0.187). Similarly, no significant association was found between gender and ever being tested (p=0.201). Further analysis examined the relationship between gender and physician referrals for HIV testing, as well as willingness to accept an HIV test if offered. Most men (84.2%, n=144) and women (82.1%, n=243) reported not being referred for testing by their primary care physician, with no significant gender-based differences (p=0.397). Regarding test acceptance, 83.6% of men (n=143) and 75.7% of women (n=224) stated they would accept testing. Although men exhibited a slightly higher acceptance rate, this difference was not statistically significant (p=0.09).

Impact of sexual activity on HIV testing

Fisher's exact test analysis assessed the relationship between recent sexual activity and HIV testing behaviors. Individuals who reported being sexually active in the past year (n=253) were significantly more likely to have ever been tested for HIV (61.1%, n=143) than those who were not sexually active (38.9%, n=84; p=0.005) (Table 3). Furthermore, willingness to accept an HIV test offered by a primary care physician was significantly associated with sexual activity (Chi-square test, p = 0.002), with sexually active individuals being approximately twice as likely to accept testing (OR = 2.048) compared to those who were not sexually active. While (57.7%, n=213) of sexually active respondents indicated they would accept testing if offered, only (40.0%, n=40) of non-sexually active individuals responded similarly (Table 4).

|

Sexually active |

Have you ever done an HIV test in your life? |

p-value (Fischer’s) |

|||

|

No (n=123) |

Yes (n=234) |

Missing (n=2) |

Total |

||

|

No |

123 (53.7%) |

91 (38.9%) |

2 (33.3%) |

216 (46.1%) |

0.005 |

|

Yes |

106 (46.3%) |

143 (61.1%) |

0 (0.0%) |

253 (53.9%) |

|

|

Total |

229 (100.0%) |

234 (100.0%) |

2 (100.0%) |

469 (100.0%) |

|

|

Sexually active response |

If a test is offered by a primary care physician, would you accept? |

p-value |

Odds Ratio |

||

|

No (n=100) |

Yes (n=369) |

Total |

|||

|

No |

60 (60.0%) |

40 (40.0%) |

100 (21.3%) |

0.002 |

2.048 |

|

Yes |

40 (40.0%) |

213 (57.7%) |

253 (53.9%) |

||

|

Total |

100 (100.0%) |

369 (100.0%) |

469 (100.0%) |

||

Influence of multiple sexual partners on testing frequency

Analysis of self-reported sexual activity with multiple partners revealed that individuals who were sexually active with multiple people were more likely to have undergone HIV testing at least once in their lifetime. Among those who reported being sexually active with multiple partners, 72.2% (n=13) had been tested for HIV, compared to 49.0% of those who were not (n=219). Only 27.8% of those reporting multiple partners had never been tested for HIV. This difference was not statistically significant (Fisher’s p=0.423) (Table 5).

Analysis of the frequency of HIV testing revealed a notable difference between participants who reported being sexually active with multiple partners and those who did not. Among those who reported not being sexually active with multiple people (n=447), the majority indicated they had never been tested for HIV (n=231; 97.1%), had been tested once in their life (n=90; 95.7%), or frequently in the past years (n=78; 92.9%). In contrast, among participants who reported being sexually active with multiple people (n=18), a relatively higher proportion reported testing every 3 months (50.0%) and every 6 months (20.0%), compared to their counterparts. Although this group represented only 3.8% of the total sample, their higher rates of frequent testing suggest increased risk perception or adherence to screening guidelines. This association was statistically significant (Chi-square p=0.033) (Table 6).

|

Sexually active response |

If a test is offered by a primary care physician, would you accept? |

p-value |

Odds Ratio |

||

|

No (n=100) |

Yes (n=369) |

Total |

|||

|

No |

60 (60.0%) |

40 (40.0%) |

100 (21.3%) |

0.002 |

2.048 |

|

Yes |

40 (40.0%) |

213 (57.7%) |

253 (53.9%) |

||

|

Total |

100 (100.0%) |

369 (100.0%) |

469 (100.0%) |

||

|

Sexually active with multiple people |

Frequency of HIV testing |

|||||||

|

N/A |

Annual |

Every 3 months |

Every 6 months |

Frequently in the past years |

Once in my life |

Total |

p-value |

|

|

No |

231 (97.1%) |

43 (93.5%) |

1 (50.0%) |

4 (80.0%) |

78 (92.9%) |

90 (95.7%) |

447 (95.3%) |

0.033 |

|

Yes |

5 (2.1%) |

3 (6.5%) |

1 (50.0%) |

1 (20.0%) |

5 (6.0%) |

3 (3.2%) |

18 (3.8%) |

|

|

Total |

238 (100%) |

46 (100%) |

2 (100%) |

5 (100%) |

84 (100%) |

94 (100%) |

469 (100%) |

|

Discussion

This study provides valuable insights into gender distribution, sexual orientation, sexual activity, HIV testing behaviors, and awareness among the surveyed population. The majority of participants were women, aligning with previous research suggesting that women may be more likely to engage in health-related surveys. Heterosexual orientation predominated, with smaller proportions identifying as homosexual or bisexual, which may reflect the demographic composition of the study population or potential underreporting due to stigma [10]. A significant finding was the relatively low rate of physician-led HIV education and referrals. Despite over half of participants reporting sexual activity within the past year, nearly 67% indicated that their primary care physician had never educated them about HIV testing, and over 82% had not been asked or referred for an HIV test (Table 1). These results highlight a critical gap in preventive healthcare communication and indicate a need for improved physician engagement in HIV education and screening.

Although the overall HIV testing rate was nearly evenly split (49.7% tested vs. 48.9% untested), those who had never been tested cited a perceived lack of necessity (73.4%). This suggests a need for targeted public health campaigns emphasizing the benefits of routine HIV screening, especially given that most participants (78.7%) stated they would accept an HIV test if offered (Table 1). The data further revealed that younger individuals were significantly more likely to have been tested and to be willing to accept testing, indicating that age-related factors influence attitudes toward HIV screening (Table 2) [11]. Gender differences in HIV testing behaviors were explored, though no statistically significant association was found. While women were slightly more likely to have been tested than men in absolute numbers, both genders reported similar testing rates (approximately 50%). Likewise, the most common reason for not being tested—"not seeing the need"—was prevalent among both men and women, further emphasizing the necessity of educational interventions.

A critical factor influencing HIV testing behavior was sexual activity. Participants who had been sexually active in the past year were significantly more likely to have been tested and to express willingness to undergo testing in the future. This aligns with existing research suggesting that individuals who perceive themselves at higher risk are more likely to engage in preventive behaviors [11]. However, among the very small subset of participants reporting multiple sexual partners, the testing rate was only 50%, and statistical significance was not reached, likely due to the limited sample size (Table 5). Larger studies are needed to examine whether individuals engaging in higher-risk behaviors are adequately utilizing HIV testing services.

Another noteworthy finding was the significant lack of awareness regarding CDC HIV testing recommendations and the availability of free testing centers. Over half of respondents were unaware of routine testing guidelines, and nearly 59% did not know that free testing centers exist (Table 1). This knowledge gap presents an opportunity for public health initiatives aimed at increasing awareness and accessibility of testing services. The statistical analyses further reinforced these observations. T-tests demonstrated that younger individuals were more likely to be sexually active, have undergone HIV testing, and be willing to accept future testing. Chi-square analyses revealed no significant gender differences in testing behaviors, reasons for not being tested, or physician referrals. However, a significant association was found between sexual activity and past HIV testing, as well as willingness to accept future testing. The relationship between multiple sexual partners and testing frequency has approached significance, suggesting that further investigation with a larger sample is warranted. Overall, these findings underscore the need for improved HIV education, physician engagement, and targeted outreach efforts. Increasing awareness of testing recommendations and reducing barriers to access—especially among those who perceive themselves at lower risk—could enhance HIV prevention strategies. Future research should explore additional psychosocial and structural factors influencing HIV testing behaviors to develop more effective interventions tailored to specific subgroups.

Conclusion

This study, conducted in a primary care center in Ponce, Puerto Rico, highlights a critical gap in preventive care and limited awareness of current HIV screening guidelines. The results revealed a concerningly high percentage of participants (66.9%) indicating that their primary care physician had not educated them about HIV testing, and 82.7% had never been asked or referred for an HIV test. Younger individuals were significantly more likely to have been tested or to express willingness to be tested if offered, suggesting lower screening engagement among older adults. Despite this willingness, persistently low rates of provider-initiated discussions reflect missed opportunities for early detection and intervention. These findings support the need for structured educational and screening programs within the Puerto Rico healthcare system. Future research should examine socio-demographic disparities and structural barriers to guide targeted interventions that improve HIV testing rates across diverse populations. Moreover, recommendations should be provided for primary care physicians to serve as advocates for public health prevention by testing their patients for HIV.

Discussion

This study provides valuable insights into gender distribution, sexual orientation, sexual activity, HIV testing behaviors, and awareness among the surveyed population. The majority of participants were women, aligning with previous research suggesting that women may be more likely to engage in health-related surveys. Heterosexual orientation predominated, with smaller proportions identifying as homosexual or bisexual, which may reflect the demographic composition of the study population or potential underreporting due to stigma [10]. A significant finding was the relatively low rate of physician-led HIV education and referrals. Despite over half of participants reporting sexual activity within the past year, nearly 67% indicated that their primary care physician had never educated them about HIV testing, and over 82% had not been asked or referred for an HIV test (Table 1). These results highlight a critical gap in preventive healthcare communication and indicate a need for improved physician engagement in HIV education and screening.

Although the overall HIV testing rate was nearly evenly split (49.7% tested vs. 48.9% untested), those who had never been tested cited a perceived lack of necessity (73.4%). This suggests a need for targeted public health campaigns emphasizing the benefits of routine HIV screening, especially given that most participants (78.7%) stated they would accept an HIV test if offered (Table 1). The data further revealed that younger individuals were significantly more likely to have been tested and to be willing to accept testing, indicating that age-related factors influence attitudes toward HIV screening (Table 2) [11]. Gender differences in HIV testing behaviors were explored, though no statistically significant association was found. While women were slightly more likely to have been tested than men in absolute numbers, both genders reported similar testing rates (approximately 50%). Likewise, the most common reason for not being tested—"not seeing the need"—was prevalent among both men and women, further emphasizing the necessity of educational interventions.

A critical factor influencing HIV testing behavior was sexual activity. Participants who had been sexually active in the past year were significantly more likely to have been tested and to express willingness to undergo testing in the future. This aligns with existing research suggesting that individuals who perceive themselves at higher risk are more likely to engage in preventive behaviors [11]. However, among the very small subset of participants reporting multiple sexual partners, the testing rate was only 50%, and statistical significance was not reached, likely due to the limited sample size (Table 5). Larger studies are needed to examine whether individuals engaging in higher-risk behaviors are adequately utilizing HIV testing services.

Another noteworthy finding was the significant lack of awareness regarding CDC HIV testing recommendations and the availability of free testing centers. Over half of respondents were unaware of routine testing guidelines, and nearly 59% did not know that free testing centers exist (Table 1). This knowledge gap presents an opportunity for public health initiatives aimed at increasing awareness and accessibility of testing services. The statistical analyses further reinforced these observations. T-tests demonstrated that younger individuals were more likely to be sexually active, have undergone HIV testing, and be willing to accept future testing. Chi-square analyses revealed no significant gender differences in testing behaviors, reasons for not being tested, or physician referrals. However, a significant association was found between sexual activity and past HIV testing, as well as willingness to accept future testing. The relationship between multiple sexual partners and testing frequency has approached significance, suggesting that further investigation with a larger sample is warranted. Overall, these findings underscore the need for improved HIV education, physician engagement, and targeted outreach efforts. Increasing awareness of testing recommendations and reducing barriers to access—especially among those who perceive themselves at lower risk—could enhance HIV prevention strategies. Future research should explore additional psychosocial and structural factors influencing HIV testing behaviors to develop more effective interventions tailored to specific subgroups.

Conclusion

This study, conducted in a primary care center in Ponce, Puerto Rico, highlights a critical gap in preventive care and limited awareness of current HIV screening guidelines. The results revealed a concerningly high percentage of participants (66.9%) indicating that their primary care physician had not educated them about HIV testing, and 82.7% had never been asked or referred for an HIV test. Younger individuals were significantly more likely to have been tested or to express willingness to be tested if offered, suggesting lower screening engagement among older adults. Despite this willingness, persistently low rates of provider-initiated discussions reflect missed opportunities for early detection and intervention. These findings support the need for structured educational and screening programs within the Puerto Rico healthcare system. Future research should examine socio-demographic disparities and structural barriers to guide targeted interventions that improve HIV testing rates across diverse populations. Moreover, recommendations should be provided for primary care physicians to serve as advocates for public health prevention by testing their patients for HIV.

References

2. Swinkels HM, Nguyen AD, Gulick PG. HIV and AIDS. 2024 Jul 27. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan–.

3. Huynh K, Kahwaji CI. HIV Testing. 2023 Apr 17. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan–.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Getting tested for HIV/CDC guidelines [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): CDC; 2024 Jul 12 [cited 2025 Jun 3]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/testing/index.html

5. Soh QR, Oh LYJ, Chow EPF, Johnson CC, Jamil MS, Ong JJ. HIV testing uptake according to opt-in, opt-out or risk-based testing approaches: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2022 Oct;19(5):375–83.

6. Syed IA, Jamil M, Bukhari SA, Malik S. A qualitative insight of HIV/AIDS patients' perspective on disease and disclosure. Health Expect. 2015 Dec;18(6):2841–52.

7. America’s HIV Epidemic Analysis Dashboard (AHEAD). America’s HIV Epidemic Analysis Dashboard: Puerto Rico [Internet]. Washington (DC): U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; [cited 2025 Jun 3]. Available from: https://ahead.hiv.gov/puerto_rico

8. Puerto Rico Department of Health. Epidemiology of HIV in Puerto Rico and the territory’s efforts to address the HIV epidemic [Internet]. San Juan (PR): Puerto Rico Department of Health; 2023 [cited 2025 Jun 3]. Available from: https://files.hiv.gov/s3fs-public/pacha-miranda-epidemiology-of-hiv-in-pr.pdf

9. Dillner J. Early detection and prevention. Mol Oncol. 2019 Mar;13(3):591–8.

10. Iott BE, Loveluck J, Benton A, Golson L, Kahle E, Lam J, et al. The impact of stigma on HIV testing decisions for gay, bisexual, queer and other men who have sex with men: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2022 Mar 9;22(1):471.

11. Appau R, Aboagye RG, Nyahe M, Khuzwayo N, Tarkang EE. Predictive ability of the health belief model in HIV testing and counselling uptake among youth aged 15-24 in La-Nkwantanang-Madina Municipality, Ghana. BMC Public Health. 2024 Jul 9;24(1):1825.