Abstract

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) is the most common inherited kidney disorder and a major cause of end-stage renal disease. The disorder is primarily caused by pathogenic variants in PKD1 or PKD2, which encode the ciliary proteins polycystin-1 and polycystin-2. Loss of polycystin function disrupts calcium and cAMP signaling within the primary cilium, altering epithelial proliferation and fluid secretion that drive cyst formation and progressive kidney enlargement. Atypical forms of ADPKD arise from variants in genes required for the production of polycystins or for ciliary assembly. Cyst growth depends on proliferative and secretory pathways involving Ca²+, cAMP, mTORC1, Src, and receptor tyrosine kinases, while chloride and water transport via CFTR, ANO1, and NKCC1 drive luminal expansion. The vasopressin V2 receptor antagonists tolvaptan remains the only approved therapy, but new approaches are under investigation. These include inhibitors of mTORC1, Src, and RTKs, agents that block chloride secretion, small molecules and microRNAs that restore or enhance polycystin expression, and emerging cyst-directed cytotoxic therapies. By targeting aberrant epithelial responses to disrupted polycystin function, therapeutic intervention can be developed to halt cyst initiation, expansion, and progression to renal failure.

Keywords

Cell communication and interactions, Cell signaling pathways, Polycystic kidney disease

Abbreviations

ADPKD: Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease; AVP: Arginine Vasopressin; ESRD: End-Stage Renal Disease; GFR: Glomerular Filtration Rate; HSP: Heat Shock Proteins; IFT: Intraflagellar Transport; MNP: Mesonanoparticles; MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging; RTK: Receptor Tyrosine Kinase; TKV: Total Kidney Volume

Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease

Pathogenesis

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) is the most common inherited renal disorder, estimated to affect approximately 1 in 1,000 individuals worldwide [1,2]. Following diabetes and hypertension, it is the third leading cause of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) [3]. The disease is inherited in a dominant pattern, giving the offspring of affected individuals a 50% chance of acquiring the disorder. In addition, approximately 10-25% of cases do not have a family history of ADPKD, suggesting that de novo mutations are prevalent [4].

ADPKD presents as a systemic disorder that typically manifests during early adulthood, although cyst formation can begin in utero [5], and disease severity and progression vary widely among patients even with the same genetic variant. Renal manifestations include progressive cyst enlargement, reduced glomerular filtration rate (GFR), and increased total kidney volume, all contributing to kidney function decline [6,7]. The expanding cysts compress adjacent nephrons and vasculature, causing chronic kidney disease and its associated complications, such as anemia, metabolic bone disease, and elevated cardiovascular risk [8]. Other features include liver and pancreatic cysts, cardiac valvular abnormalities, intracranial aneurysms, nephrolithiasis, cyst hemorrhage, hematuria, abdominal wall hernias, and recurrent urinary tract infections [5].

Most ADPKD arises from variants in either the PKD1 or PKD2 gene. PKD1, located on chromosome 16, encodes polycystin-1, a large multidomain glycoprotein, and accounts for about 78% of cases [9,10]. PKD2, located on chromosome 4, encodes polycystin-2, a calcium-permeable cation channel in the transient receptor potential family, and accounts for about 15% of cases [9,11]. There are more than 1,500 unique variants in PKD1 and PKD2 [12]. Genetic screening can enable family risk assessment and improved patient stratification as allelic variation predicts ADPKD progression. Specifically, PKD1 variants leading to faster ESRD onset than PKD2 variants and truncating changes conferring greater pathogenicity than non-truncating [13]. Minor or atypical PKD genes are still being discovered and currently include genes like IFT140 [14], GANAB [15], ALG8 [16], and ALG9 [17]. GANAB, ALG8, and ALG9 are thought to promote the biosynthesis of polycystins [18], while IFT140 is part of the intraflagellar transport (IFT) system needed to assemble cilia [19,20].

The ADPKD gene products polycystin-1 and polycystin-2 are localized to primary cilia of renal epithelial cells [21,22]. Primary cilia are non-motile organelles that extend from the surface of most cells, including the epithelial cells of the kidney tubule. Defects in kidney cilia lead to cystic disease [23]. In the kidney tubule, primary cilia detect fluid shear stress or a chemical cue that reports the tubule diameter and controls the proliferation of the tubule epithelium. Kidney primary cilia, like other cilia, are microtubule-based organelles composed of 500-1,000 or more unique proteins [24]. These proteins are synthesized in the cell body and transported into cilia by IFT. During IFT, large protein complexes called IFT particles are transported along ciliary microtubules by kinesin-2 [25] and dynein-2 [26] motors. These particles are made of IFT-A, IFT-B, and BBSome subcomplexes and serve as motor adaptors, allowing a single pair of motors to transport the diverse cargos needed to build and maintain cilia. IFT140, a leading cause of atypical ADPKD, is a subunit of IFT-A. Biallelic mutations that affect the IFT system may block or partially disrupt ciliary assembly and cause cystic disease as part of a syndrome that includes skeletal dysplasia, retinal degeneration, and other organ malformations [27]. The recent finding of dominant forms of cystic disease caused by monoallelic disruptions in IFT140 suggests that haploinsufficiency or loss of the functional allele drives disease in these individuals [14,28].

In addition to IFT defects, variants that affect the ciliary transition zone at the ciliary base are a leading cause of the cystic disease nephronophthisis [29]. Nephronophthisis causes cysts at the cortical medullary boundary and the loss of kidney mass [29–31]. This cystic kidney disease is often associated with retinal degeneration in Senior-Loken syndrome and brain malformations in Joubert syndrome [32,33]. The transition zone comprises about 20 proteins that link extensively between the microtubule cytoskeleton and the ciliary membrane [29]. The transition zone functions as a selective barrier, regulating the entry and exit of proteins and signaling molecules essential for ciliary integrity [34]. The pathomechanism of NPHP is still not entirely clear but recent studies suggest an inflammatory contribution [35] and that prostaglandin E receptor agonists could potentially be beneficial as suggested by preclinical data [36].

Cyst initiation models

The leading model of cyst formation in ADPKD is the "second hit" model, which posits that patients inherit one loss-of-function allele. Similar to the mechanism of tumor suppressors, ADPKD initiates with the stochastic loss of the second allele. This second-allele loss initiates a clonal expansion of epithelial cells, a process supported by proliferative and secretory pathways. Alternative models include the "third hit" and the "haploinsufficiency hypothesis." In the third hit model, a second hit is insufficient to initiate cyst expansion and kidney injury is needed to initiate cyst expansion after the loss of the second allele. The haploinsufficiency hypothesis suggests that a single copy of the polycystins is insufficient to maintain tubule structure and that, with time, cysts arise without the need to lose the second allele.

Support for the second-hit hypothesis comes from studies of cystic cells isolated from affected patients. The second hit hypothesis suggests that an inactivating mutation would initiate a cyst, and the cells of a cyst would derive from clonal expansion. A methylation-sensitive assay that tracked cells due to random X-inactivation [37] found strong evidence for clonal expansion within cysts. More recent attempts to test this hypothesis used genome sequencing to determine if the cells of a cyst all contain the original second hit. Several studies of isolated cysts found that many cells have the same somatic mutation, supporting the second hit hypothesis [38,39]. Furthermore, these studies found wide evidence for truncating and non-truncating somatic mutations and loss of heterozygosity at the PKD1 or PKD2 loci, supporting the hypothesis that ADPKD initiates with the loss of the normal allele [38,39]. Mouse models also support the second-hit hypothesis. The Pkd2-/WS25 mouse model carries an unstable but functional Pkd2 allele. Over time, recombination converts the unstable allele to a loss-of-function allele, resulting in slowly progressive disease [40,41].

Animal studies strongly support the third-hit hypothesis, suggesting kidney injury modifies disease progression. In mice, polycystin loss during the early postnatal period before about day 13 leads to rapid cyst growth. In contrast, loss of the polycystins after this point leads to slow disease progression and changes the nature of the pathology. Disease initiation in the early postnatal period affects many, if not most, tubules, causing the kidney to be filled with small cysts whereas the later loss of gene function leads to focal cystic disease with a few large cysts [42]. Ischemia-reperfusion injury accelerates disease progression in Pkd1 mutant mice by engaging impaired injury response mechanisms that promote aberrant epithelial proliferation, leading to rapid, widespread cyst formation in the affected kidney [43–45].

Haploinsufficiency in ADPKD refers to insufficient production of functional polycystins, resulting in dose-related disease severity. This idea is supported by the observation that some human cysts do not appear to have second hits when sequenced [38,39]. The idea is well supported by mouse models. Studies of an allelic series including a Pkd2 null and the unstable Pkd2WS25 allele showed that cysts could form without complete loss of the polycystin-2 and that polycystin-2 expression inversely correlated with the severity of cystic phenotype [41]. A similar pattern occurs in Pkd1nl mice that express reduced levels of wild-type polycystin-1 due to a splicing defect. Mice homozygous for this allele developed cystic kidney disease even though all cells still express some polycystin-1 [46]. Similarly, studies with the Pkd1RC allele support haploinsufficiency. This allele, derived from a human patient, is hypomorphic, and mice homozygous for this allele develop a slow-progressing cystic phenotype [47].

Calcium signaling in ADPKD

The primary sequence of the polycystins suggests that they regulate intracellular calcium levels [10,11]. The phenotypes caused by PKD1 and PKD2 variants are similar, indicating they are likely to work together. However, PKD1 expression is higher in development [48] while PKD2 is maintained post-development [49], and polycystin-1 was found on the cell surface [50] whereas polycystin-2 was found in the endoplasmic reticulum [51] raising questions about whether they acted together. Cryo structures clearly show that a polycystin complex composed of one polycystin-1 and three polycystin-2 subunits form [52], and the finding of both polycystins in cilia provided a common site for action [21,22].

The current hypotheses suggest that a ciliary localized polycystin-1/polycystin-2 complex monitors tubule diameter and regulates calcium influx to control proliferation. The flow hypothesis is the leading model for the mechanism of tubule diameter sensing by the kidney cilia. This hypothesis started with work in Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells, where bending the primary cilia with suction from a micropipette increased intracellular calcium as measured using a calcium indicator. Fluid flow also elevated intracellular calcium, with calcium-sensitive fluorescence intensity rising proportionately to the flow rate [53]. Following this, Nauli and colleagues [54] reproduced the calcium influx induced by flow and demonstrated that genetic loss of PKD1 or perturbation of polycystin-2 by antibody treatment blocked the flow-induced calcium influx. This finding has been reproduced in subsequent studies [55–57], but later work questioned the biophysics of ciliary calcium influencing cytoplasmic calcium levels. Work from Delling and colleagues showed that mouse embryonic fibroblast cilia exposed a PKD1L1-PKD2L1 channel to the environment and this channel was able to alter the ciliary calcium levels without altering the non-ciliary cytoplasmic levels [58]. These investigators re-examined whether flow could induce calcium elevations in cilia but failed to detect elevations in response to flow in kidney epithelium or other cells. They further showed that disrupting the ciliary membrane could elevate ciliary calcium, but ciliary influx was insufficient to alter cytoplasmic calcium [59]. A further challenge to the flow detection model came from in vivo imaging that showed that under normal conditions of flow through the tubule, cilia are fully deflected against the tubule wall [60], a condition that would be expected to promote pro-proliferative signaling. Alternatively, cilia could detect ligands that report tubule diameter. The biophysics of the mechanism has not been worked out, but polycystin-1 bound Wnt ligands induced a calcium response [61]. While the loss of cilia and the loss of polycystin-1 both result in cystic kidneys, loss of cilia in Pkd1 mouse models reduced cysts compared to the loss of either alone, suggesting a cyst-promoting mechanism occurs in absence of polycystin-1 that requires a cilium to become effective [62].

Whether polycystins function primarily in cilia is debated, as they are also present in other cellular locations. The leading non-ciliary sites are cell-cell junctions and the endoplasmic reticulum. Polycystin-2 is particularly abundant in the endoplasmic reticulum, which may be important for cellular calcium homeostasis [63]. Regardless of the importance of non-ciliary polycystin pools, cilia are critical for maintaining kidney structure as mutations that disrupt cilia lead to cystic disease [23], and mutations that block ciliary accumulation of polycystin-2 without affecting other functional parameters cause PKD [64]. In addition, many pathogenic PKD1 missense variants disrupt ciliary localization without apparent effects on channel properties [65].

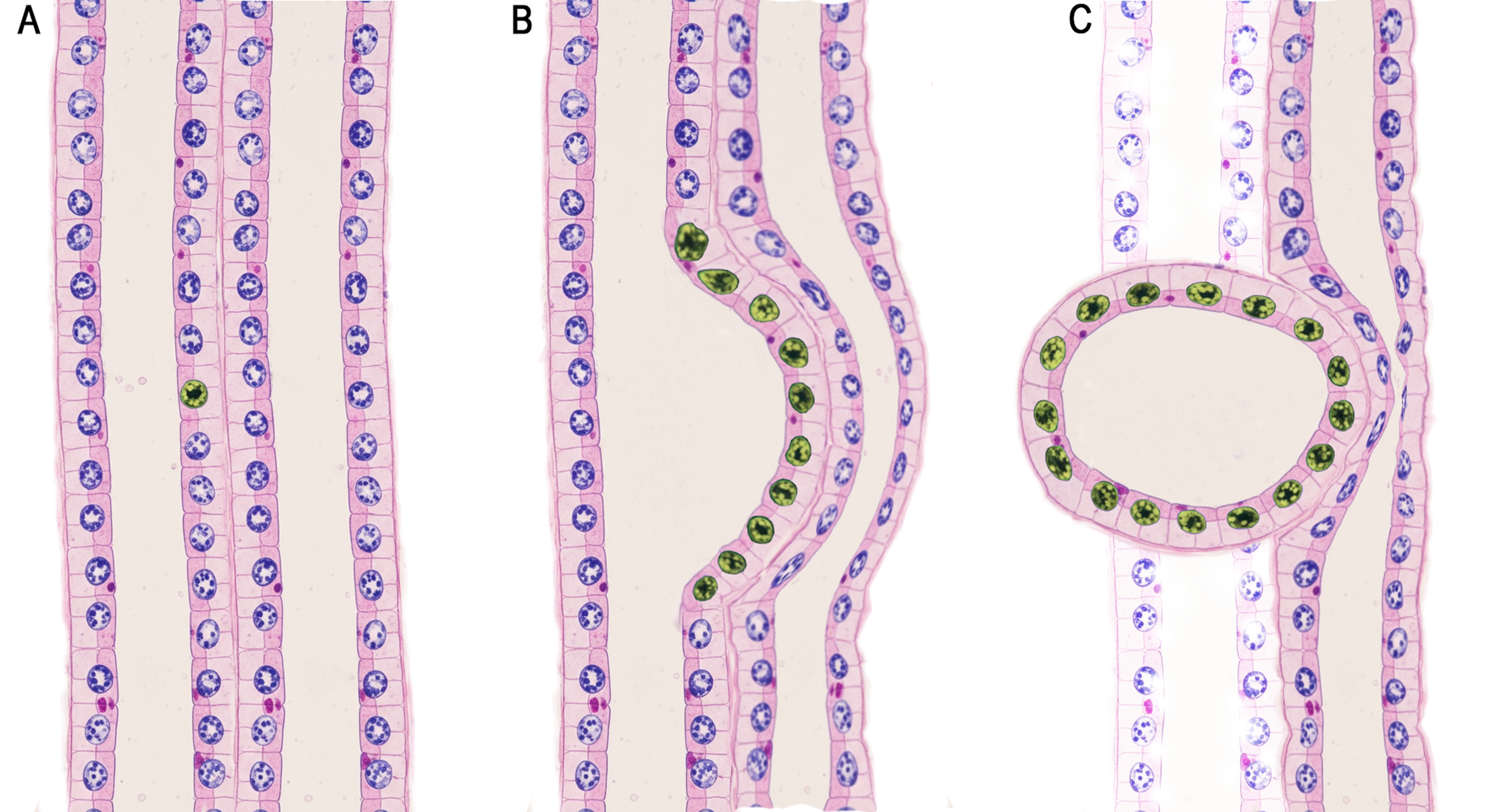

Figure 1. Schematic of clonal expansion and cyst initiation in nephron tubule epithelium. (A) The two-hit hypothesis proposes that cyst expansion is initiated by a single mutated epithelial cell within the nephron tubule. (B) Localized monoclonal proliferation leads to segmental tubule dilation and cyst formation. (C) As the cyst separates from the originating tubule, its continued growth causes mechanical compression of surrounding vasculature, triggering inflammation, fibrosis, hemorrhage, and infection. Cyst expansion contributes to tubular ischemia, obstruction, and epithelial injury, accompanied by the release of proinflammatory mediators and progressive disruption of normal tubular structure, renal architecture, and function.

cAMP signaling in ADPKD

Compared with healthy kidney cells, ADPKD renal epithelial cells have elevated levels of cAMP and exhibit heightened proliferative responses to this second messenger [66–68]. The elevated cAMP is likely the result of reduced intracellular calcium which relieves inhibition of adenylyl cyclases, particularly AC5 and AC6 [66,69,70]. Consistent with this, Pkd1 and Ac6 double-knockout mice develop fewer and smaller cysts than Pkd1 mutants alone and maintain improved renal function [71]. Similarly, double knockout of Pkd2 and Ac5 reduces hepatic cysts, suggesting that analogous ciliary cAMP mechanisms operate in cholangiocytes [72]. Evidence suggests that localized cAMP signaling is particularly important. For example, low vasopressin concentrations stimulate proliferation in ADPKD cells without a measurable increase in total intracellular cAMP [73]. Additionally, Hansen et al. showed that ciliary rather than cytosolic cAMP drives cystogenesis [74].

Therapeutic Approaches for Reducing Cyst Burden in ADPKD

The conversion of a kidney tubule to a cyst will destroy the nephron or collecting duct where the cyst initiates. As the cyst enlarges, it will compress the surrounding normal tubules and vasculature, contributing to a decline in kidney function. Approaches that prevent the initiation of cysts, prevent the proliferation or cause the death of cystic cells, or prevent the expansion of cysts caused by fluid secretion could show therapeutic effects. This review outlines emerging strategies that target cyst epithelial proliferation and fluid secretion and also highlight approaches for selective cyst elimination by exploiting oxidative stress susceptibility or exploiting cyst-specific surface markers for drug delivery (Table 1).

|

Target/Pathway |

Drug |

Status |

Mechanism of Action |

|

cAMP |

Tolvaptan |

FDA approved |

Vasopressin V2 receptor antagonist; reduces cAMP, slowing proliferation |

|

mTOR |

Sirolimus (Rapamycin) |

Clinical trial did not show efficacy |

Inhibits the mTOR pathway, which controls cell growth and proliferation |

|

Everolimus |

Clinical trial did not show efficacy |

||

|

Rapamycin on nano particles |

Mouse (Pkd1) studies were not successful |

||

|

Receptor Tyrosine Kinases |

Nintedanib |

Mouse (Pkd1) studies showed efficacy |

Inhibits tyrosine kinases involved in cell proliferation and renal fibrosis |

|

Non-Receptor Tyrosine Kinases |

Bosutinib |

Clinical trial showed reduced rates kidney enlargement but similar eGFR decline compared to placebo |

Regulate proliferation, differentiation, and survival via c-Src signaling |

|

Tesevatinib |

In clinical trial |

||

|

CFTR chloride secretion |

GLPG2737 |

Clinical trial did not show efficacy |

Inhibits wild-type CFTR chloride channel |

|

ANO1 chloride secretion |

Niclosamide |

Mouse (Pkd1) studies showed efficacy |

Inhibits ANO1 (TMEM16A), a calcium-activated chloride channel |

|

Benzbromarone |

Mouse (Pkd1) studies showed efficacy |

||

|

Ani9 |

Mouse (Pkd1) studies showed efficacy |

||

|

NKCC1 ion transport |

Bumetanide |

Cell based studies showed efficacy |

Inhibits NKCC1 transporter, reducing chloride-driven fluid secretion |

|

Polycystin Folding and Maturation |

VX-809 |

Mouse (Pkd1) studies showed efficacy |

Chaperones or correctors that improve folding and trafficking of the polycystins |

|

C18 |

Cell based studies showed efficacy |

||

|

VRT-325 |

Cell based studies showed efficacy |

||

|

STA-2842 |

Mouse (Pkd1) studies showed efficacy |

||

|

Increasing Polycystin Expression |

RGLS4326 |

In clinical trial |

miR-17 inhibitors; increase polycystin expression |

|

RGLS8429 |

In clinical trial |

||

|

Cytotoxic Agents |

11beta-dichloro |

Mouse (Pkd1) studies showed efficacy |

Target cyst-lining cells for selective cytotoxicity |

|

11beta-dipropyl |

Mouse (Pkd1) studies showed efficacy |

||

|

Dimeric cMET antibody |

Successfully reduced cyst growth in a rapidly progressing (Bpk) but not in slow developing (Pkd1) mouse models |

||

|

TACSTD2 antibody drug conjugates |

Not tested |

Targeting cyst growth through modulation of pro-proliferative signaling

Increased proliferation is thought to be a primary driver of cyst growth and numerous pathways have been identified that promote proliferation. This section discusses efforts to target these pathways to slow or stop proliferation.

cAMP: As part of the kidney’s function in regulating systemic homeostasis, increased plasma osmolality, reduced blood pressure, or reduced blood volume triggers arginine vasopressin (AVP) release from the pituitary gland [75]. AVP acts through three G protein-coupled receptors: V1aR, V1bR, and V2R [76]. V2R localizes to epithelial cells in the thick ascending limb, connecting tubules and collecting ducts, where it regulates cAMP signaling to promote fluid retention [77]. In addition to its antidiuretic effect, AVP promotes proliferation in V2R-expressing renal epithelium [73,76]. Interestingly, V2R inhibition, not V1aR or V1bR, blunts AVP-induced proliferation [76]. Distal tubule and collecting duct cells express V2R and are the predominant cell types contributing to cyst formation [78]. In ADPKD, AVP levels are elevated, promoting disease progression by increasing cAMP -driven proliferation [79,80]. PCK rats lacking AVP exhibit fewer ADPKD-related phenotypes, including reduced renal cAMP, kidney weight, and cyst burden [79]. V2R inhibitor OPC31260 reduced cyst growth, renal enlargement, and epithelial proliferation in PCK rats, Pkd2−/tm1Som mice, and Pkd2WS25/- mice [81–83].

The studies in rodents showing that V2R was a driver of cyst growth supported the advancement of tolvaptan into clinical development [79]. The TEMPO 3:4 and REPRISE trials evaluated tolvaptan's efficacy in patients with ADPKD [84,85]. In TEMPO 3:4, tolvaptan reduced total kidney volume (TKV) growth by 49% and slowed eGFR decline by 26% over three years in early-stage disease [84]. REPRISE demonstrated a 35% reduction in eGFR decline over one year in later-stage ADPKD [85]. Adverse effects included polyuria, thirst, and hepatotoxicity [85]. TEMPO 3:4 supported FDA approval for use in patients with rapidly progressing disease, while REPRISE confirmed efficacy in more advanced stages. Limited tolerability and elevations in liver enzymes constrain the clinical use of tolvaptan. Nonetheless, V2R antagonism remains the only approved pharmacologic approach for ADPKD.

mTORC1: In ADPKD mouse models, mTORC1 signaling is upregulated, promoting cell growth and proliferation, which are thought to contribute to cyst expansion [86,87]. The mTORC1 inhibitor rapamycin reduced ADPKD epithelial proliferation and improved total kidney volume, kidney-to-body weight ratios, and blood urea nitrogen in mouse models of ADPKD [86,88,89]. These findings led to clinical trials of rapamycin (Sirolimus) and Everolimus, a rapamycin derivative with better oral bioavailability and shorter half-life. The drugs had significant side effects, and neither drug showed efficacy in the trials, so the trials were discontinued. A major concern in the trials was whether the effective drug dose was high enough to inhibit mTORC1 signaling in the cystic epithelium [90–93].

Building on limitations observed with free rapamycin, nanoparticle-based formulations called mesonanoparticles have been developed to enhance kidney-specific delivery. While these particles typically accumulate in the liver and spleen, they can be targeted to the kidney proximal tubule by controlling size [94]. Particles loaded with rapamycin effectively inhibited mTORC1 signaling in the kidney but did not reduce cyst growth in a slow-onset adult model of ADPKD [95]. However, further analysis is warranted as this model developed a very mild disease, and it is unclear whether efficacy would be demonstrated in the treatment timeframe. Furthermore, the Cagg-CreER driver used for Pkd1 deletion would have also deleted the gene in the distal tubule beyond the proximal tubule where the MNPs are enriched.

Receptor tyrosine-kinases: Several receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) converge on shared downstream effectors to activate signaling pathways that regulate cell proliferation and fibrogenesis [96–100]. In ADPKD, aberrant proliferation drives cyst expansion, while fibrosis contributes to progressive renal dysfunction [96–98]. Under normal conditions, RTK signaling is regulated by ligand-induced degradation to prevent sustained activation [101]. Pkd1null/null cells exhibit impaired RTK degradation following stimulation, resulting in persistent activation of downstream effectors such as mTORC1, leading to disease progression [101]. In five-month-old Pkd1RC/RC mice, RTKs PDGFRβ and FGFR1 are elevated [102]. Nintedanib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor FDA-approved for pulmonary fibrosis, blocks autophosphorylation of multiple growth factor receptors, including FGFR, PDGFR, and VEGFR [98,102]. In vitro, nintedanib reduced proliferation of human ADPKD cystic epithelial cells compared to untreated and significantly reduced cyst growth when ADPKD cells were cultured in a 3D collagen matrix [102]. Pkd1RC/RC and Pkd1-/- ADPKD mice treated with nintedanib exhibited significantly decreased cyst growth, TKV, blood urea nitrogen, and fibrosis [102].

Src: The non-receptor tyrosine kinase c-Src transduces extracellular mitogenic stimuli to signaling networks that govern proliferation, differentiation, and survival [103]. Initially identified as an oncogene, c-Src promotes malignant proliferation [103–105]. c-Src is phosphorylated by PKA in response to elevated cAMP levels, suggesting that it may be a good target for therapeutic intervention in ADPKD [106]. Bosutinib, an FDA-approved oral Src/Bcr-Abl tyrosine kinase inhibitor for chronic myeloid leukemia, showed protective effects in Pkhd1 [107] and Pkd1 [108] rat and mouse models of cystic disease. A clinical trial showed reductions in total kidney volume, but Bosutinib had minimal effects on maintaining kidney function [109]. Tesevatinib, which is a kinase inhibitor that targets multiple kinases, including c-Scr, was effective in Pkhd1 rat and Bicc1 mouse models of cystic disease [110] and a clinical trial was undertaken, but results have not been published (clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT01559363).

Targeting Cyst Expansion Through Modulation of Secretion

Luminal fluid accumulation is likely to promote cyst expansion and enlarging cysts that impinge on healthy tubules likely drive renal functional decline. Fluid movement into cysts is thought to be driven by chloride transport across the apical surface via the CFTR and ANO1 transporters with cellular chloride replenished via NKCC1 basal lateral transport. This section discusses various approaches that are being explored as therapeutic options to reduce fluid movement into cysts.

Fluid accumulation in cysts is thought to result from a cAMP-facilitated movement of chloride across the apical surface which is supported by basolateral reuptake [111]. The apical chloride transporters are likely CFTR [112] and ANO1 (also known as TMEM16A) [113], while the basolateral transporter is likely the Na-K-2Cl symporter (NKCC1) [114,115]. In the kidney, CFTR is present on the tubule epithelial apical surface and retains its apical location in cystic epithelium [116]. Studies of a limited number of patients carrying CFTR and ADPKD variants found that patients with CFTR and ADPKD variants had less severe cystic disease than family members with only the ADPKD variant [117,118]. The beneficial nature of CFTR loss was supported in metanephric culture, where the loss of CFTR protected Pkd1 mutant embryonic kidneys from cyst formation caused by 8-Br-cAMP treatment [119]. In contrast, CFTR loss was not protective against cyst formation in an early adult-onset mouse model of cystic disease driven by tamoxifen-induced knockout of Pkd1 and Cftr1 [120].

As discussed below, work in the CFTR field has identified small molecule effectors of CFTR activity. One compound GLPG2737 can promote the activity of the CFTRdelF508 pathogenic variant while inhibiting wild-type CFTR in a dose-dependent manner [121]. The inhibitory effect of this drug to suppress CFTR-mediated chloride secretion has potential to be beneficial in ADPKD. Preclinical models of ADPKD demonstrated that GLPG2737 reduced cyst burden in forskolin-treated metanephric kidney explants and in both rapid and slow progression mouse models i.e., KspCreERT2-Pkd1lox/lox and Pkd1RC/RC mice, respectively [122]. In these models, GLPG2737 also decreased the kidney-to-body weight ratio and preserved renal function [122]. When combined with tolvaptan, GLPG2737 further suppressed cyst expansion and reduced intracellular cAMP levels [122]. Despite promising preclinical data, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled Phase 2 trial (NCT04578548) evaluating this drug in ADPKD was terminated due to lack of efficacy. This outcome may reflect insufficient CFTR inhibition by the administered dose, especially since Pkd1 loss increases CFTR expression [120]. Given its tolerability in clinical studies (NCT03410979), higher doses of GLPG2737 may be possible to achieve therapeutic CFTR suppression in ADPKD [123].

In addition to CFTR, ANO1 likely contributes to chloride-driven secretion in cyst expansion. ANO1 is a calcium-activated chloride channel upregulated in cystic epithelia of Pkd1-/- mice. Genetic ablation of ANO1 reduced cyst growth in animal models. Additionally, treatment of Pkd1-/- mice with ANO1 inhibitors, including niclosamide, benzbromarone, and Ani9, an ANO1-specific small molecule inhibitor, significantly slowed disease progression and decreased proliferation in renal tubular epithelial cells [113]. Currently none of these drugs have been tested in human trials. The role of ANO1 may be more complicated as ANO1 has been shown to localize to primary cilia and knockdown of expression or drug-mediated inhibition reduced cilia length [124], which could have indirect effects on cyst growth [62].

NKCC1, a basolateral Na+, K+, 2Cl- cotransporter, mediates chloride reabsorption in renal epithelial cells. In ADPKD kidneys, NKCC1 and CFTR are co-expressed on some but not all cystic epithelium and function cooperatively to support chloride-driven fluid secretion [114,115,125]. Cell-based studies showed that pharmacologic inhibition of NKCC1 with bumetanide suppressed cAMP-driven cyst growth in response to forskolin and IBMX, implicating basolateral chloride influx in cyst expansion [112]. Bumetanide is being tested for benefits to chronic kidney disease (NCT03923933) but has not been explored in human trials of ADPKD.

Targeting cyst growth through increased polycystin activity

The ADPKD-driving alleles in many patients are missense variants that could potentially retain some activity. Strategies to increase cell surface exposure of these variants have potential to reduce disease severity. Approaches include improving the biosynthesis of the polycystin variants through modulation of folding and by increasing gene expression with micro RNAs.

Improved folding and maturation: Misfolded membrane proteins often accumulate in the endomembrane system during biosynthesis and fail to reach the cell surface. Drugs that improve folding and maturation of pathogenic CFTR variants have proven effective in the treatment of cystic fibrosis [126–129]. Since many ADPKD variants are likely to also affect the folding and maturation of the polycystins, this approach may also be effective in cystic disease.

The small molecule VX-809 improves folding and trafficking of CFTR, allowing it to reach the cell surface and function more effectively [130]. Evidence that VX-809 might work more generally to assist folding of membrane proteins prompted studies in ADPKD. In forskolin-induced cystic organoids, VX-809 and C18 (a compound with similar activity to VX-809) reduced cyst area and in mouse Pkd1–/– models, VX-809 reduced cAMP levels and epithelial proliferation [128,131]. Another small molecule, CFTR corrector VRT-325 improved the processing, maturation, and trafficking of CFTRdelF508 to the cell surface [130,132,133]. In mouse inner medullary collecting duct cells, treatment with VRT-325 increased ciliary levels of Pkd1 missense variants that otherwise failed to localize to the primary cilium [65] suggesting that this approach has potential in ADPKD, but it has not been tested in clinical trial.

An alternative approach is to perturb the heat shock proteins themselves to reduce the adverse effects of misfolded proteins. One Hsp90 inhibitor, STA-2842, suppressed cyst growth, decreased kidney-to-body weight ratio, and improved renal function in Pkd1–/– mice without adverse effects in wild-type mice [129] but it has not been tested in clinical trial. An alternative mechanism proposes that Hsp90 inhibition promotes primary cilia resorption and dysregulates cilia-associated proteins, a process previously shown to mitigate cystic progression caused by polycystin-1 or polycystin-2 loss [62,134].

Increased Expression: MicroRNAs are short, non-coding RNAs that regulate gene expression by binding to complementary sequences on target mRNAs, leading to post-transcriptional control of protein production. Members of the miR-17~92 cluster were upregulated in Kif3a-knockout mouse kidneys, where the loss of this IFT kinesin II motor protein disrupts primary cilia and results in polycystic kidney disease [135,136]. Overexpression of the cluster in renal tubules increased epithelial proliferation, promoted cyst formation, and reduced expression of cyst-associated genes, including Pkd1, Pkd2, Pkhd1, and Hnf1b while kidney-specific inactivation of the cluster reduced cyst growth [136]. In addition to the miR-17~92 cluster, miR-21 is also elevated in the cyst-lining epithelium in both murine and human ADPKD kidneys. In Pkd2-deficient mice, genetic deletion of miR-21 reduced cyst burden, improved renal function, and extended survival. Functionally, miR-21 is thought to inhibit apoptosis in cyst-lining cells, and thus its loss enhances cell death [137].

A targeted screen within the miR-17~92 cluster identified the miR-17 family as the primary contributor to cyst growth in ADPKD as inhibition of miR-17 reduced total kidney volume, cystic burden, and epithelial proliferation in Pkd1-/- and Pkd2-/- ADPKD mouse models [138–140]. RGLS4326, a chemically modified antisense oligonucleotide, inhibits miR-17 activity and selectively accumulates in the kidney. Treatment with this compound increased polycystin-1 and polycystin-2 levels, reduced cyst growth in ADPKD patient-derived organoids, and improved renal function in Pkd2-deficient mouse models [138]. Phase1 clinical trials of RGLS4326 (NCT04536688) and the related drug RGLS8429 (NCT05429073) have recently been completed but not yet published.

Targeting cysts with cytotoxic agents

An alternative approach to preventing cyst expansion would be to selectively kill cystic cells to prevent their proliferation. This idea was recently tested in two studies [141,142]. The first examined 11beta-dichloro, which stimulates apoptosis in cancer cells by exacerbating mitochondrial oxidative stress and causing DNA damage via alkylating activity. Treatment with 11beta-dichloro reduced cyst burden, decreased kidney volume, and improved renal function in both rapid and slow progressing mouse models. Apoptosis driven by this agent was limited to cyst-lining cells, with minimal effect on non-cystic tubule cells. Treatment also reduced fibrosis as indicated by decreased αSMA and PDGFRβ expression. A structurally related compound, 11beta-dipropyl, which lacks DNA alkylating activity, produced comparable effects, suggesting oxidative injury alone may be sufficient to induce cyst-selective cytotoxicity [141]. No clinical trials have been reported of either drug. The second study took advantage of the property of cystic epithelium to transcytose polymeric immunoglobins. An engineered dimeric monoclonal antibody directed against the cMET receptor was effectively taken up by cystic cells and reduced the levels of cMET in cyst lining cells. cMET is thought to stimulate protection against oxidative damage in cells with high metabolism. The treatment increased apoptosis of cyst lining cells and reduced the two-kidney to body weight ratio as well as the cystic index in the rapidly progressing Bpk mouse model of cystic disease. In a slower developing adult-onset model of Pkd1, treatment reduced the size of individual cysts but did not reduce the two-kidney to body weight ratio [142]. However, the mice were not followed for an extended period, and it is possible that the effects were not yet evident.

While untested in vivo, another approach targets cyst-lining cells with antibody-drug conjugates that carry anti-cystic drugs. This approach is being used successfully in oncology, where TACSTD2 is used as a molecular beacon to deliver cytotoxic drugs [143]. TACSTD2 (also known as TROP2) is an attractive target as its expression is generally low in most tissues but is highly upregulated in many solid tumors [144]. Two antibody-drug conjugates targeting TACSTD2 for delivery of cytotoxic drugs are FDA-approved for breast and bladder cancer [145–147]. Using RNA sequencing, we found that TACSTD2 is upregulated shortly after the deletion of Pkd2 in a mouse model and showed elevated expression in human cyst biopsies and cystic organoids [148]. TACSTD2 overexpression in cystic epithelium supports adapting oncology-based therapeutic strategies for ADPKD. This would require the development of new antibody-drug conjugates appropriate to treat ADPKD but could potentially target cystic cells specifically to prevent cyst expansion.

Summary

The FDA approval of tolvaptan was a major step in the development of treatment for ADPKD. However, the significant limitations of this drug make it imperative that new treatments are developed. As described in this review, the disease has a number of druggable targets and considerable energy is being expended to identify active compounds. Future work by both basic scientists and clinicians is needed to move the most promising of these drugs from the laboratory to the patient while continuing to explore the mechanism by which the polycystins regulate tubule diameter and prevent the development of cysts.

Acknowledgements

Work was supported by NIH GM060992 (GJP).

Competing Interests

A provisional patent has been filed: US Application No.: 63/589,316 THERAPY FOR POLYCYSTIC KIDNEY DISEASE.

References

2. Lanktree MB, Haghighi A, Guiard E, Iliuta IA, Song X, Harris PC, et al. Prevalence Estimates of Polycystic Kidney and Liver Disease by Population Sequencing. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018 Oct;29(10):2593–600.

3. Zhou X, Torres VE. Emerging therapies for autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease with a focus on cAMP signaling. Front Mol Biosci. 2022 Sep 2;9:981963.

4. Reed B, McFann K, Kimberling WJ, Pei Y, Gabow PA, Christopher K, et al. Presence of de novo mutations in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease patients without family history. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008 Dec;52(6):1042–50.

5. Bergmann C, Guay-Woodford LM, Harris PC, Horie S, Peters DJM, Torres VE. Polycystic kidney disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018 Dec 6;4(1):50.

6. Parajuli S, Mandelbrot DA, Aziz F, Garg N, Muth B, Mohamed M, et al. Characteristics and Outcomes of Kidney Transplant Recipients with a Functioning Graft for More than 25 Years. Kidney Dis (Basel). 2018 Nov;4(4):255–61.

7. Chebib FT, Perrone RD, Chapman AB, Dahl NK, Harris PC, Mrug M, et al. A Practical Guide for Treatment of Rapidly Progressive ADPKD with Tolvaptan. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018 Oct;29(10):2458–70.

8. Righini M, Mancini R, Busutti M, Buscaroli A. Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease: Extrarenal Involvement. Int J Mol Sci. 2024 Feb 22;25(5):2554.

9. Chebib FT, Hanna C, Harris PC, Torres VE, Dahl NK. Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease: A Review. JAMA. 2025 May 20;333(19):1708–19.

10. The European Polycystic Kidney Disease Consortium. The polycystic kidney disease 1 gene encodes a 14 kb transcript and lies within a duplicated region on chromosome 16. The European Polycystic Kidney Disease Consortium. Cell. 1994 Jun 17;77(6):881–94.

11. Mochizuki T, Wu G, Hayashi T, Xenophontos SL, Veldhuisen B, Saris JJ, et al. PKD2, a gene for polycystic kidney disease that encodes an integral membrane protein. Science. 1996 May 31;272(5266):1339–42.

12. Mallawaarachchi AC, Furlong TJ, Shine J, Harris PC, Cowley MJ. Population data improves variant interpretation in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Genet Med. 2019 Jun;21(6):1425–34.

13. Lanktree MB, Kline T, Pei Y. Assessing the Risk of Progression to Kidney Failure in Patients With Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. Adv Kidney Dis Health. 2023 Sep;30(5):407–16.

14. Senum SR, Li YSM, Benson KA, Joli G, Olinger E, Lavu S, et al. Monoallelic IFT140 pathogenic variants are an important cause of the autosomal dominant polycystic kidney-spectrum phenotype. Am J Hum Genet. 2022 Jan 6;109(1):136–56.

15. Porath B, Gainullin VG, Cornec-Le Gall E, Dillinger EK, Heyer CM, Hopp K, et al Mutations in GANAB, Encoding the Glucosidase IIα Subunit, Cause Autosomal-Dominant Polycystic Kidney and Liver Disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2016 Jun 2;98(6):1193–207.

16. Besse W, Dong K, Choi J, Punia S, Fedeles SV, Choi M, et al. Isolated polycystic liver disease genes define effectors of polycystin-1 function. J Clin Invest. 2017 May 1;127(5):1772–85.

17. Besse W, Chang AR, Luo JZ, Triffo WJ, Moore BS, Gulati A, et al. ALG9 Mutation Carriers Develop Kidney and Liver Cysts. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019 Nov;30(11):2091–102.

18. Mahboobipour AA, Ala M, Safdari Lord J, Yaghoobi A. Clinical manifestation, epidemiology, genetic basis, potential molecular targets, and current treatment of polycystic liver disease. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2024 Apr 26;19(1):175.

19. Cole DG. The intraflagellar transport machinery of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Traffic. 2003 Jul;4(7):435–42.

20. Jonassen JA, SanAgustin J, Baker SP, Pazour GJ. Disruption of IFT complex A causes cystic kidneys without mitotic spindle misorientation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012 Apr;23(4):641–51.

21. Pazour GJ, San Agustin JT, Follit JA, Rosenbaum JL, Witman GB. Polycystin-2 localizes to kidney cilia and the ciliary level is elevated in orpk mice with polycystic kidney disease. Curr Biol. 2002 Jun 4;12(11):R378–80.

22. Yoder BK, Hou X, Guay-Woodford LM. The polycystic kidney disease proteins, polycystin-1, polycystin-2, polaris, and cystin, are co-localized in renal cilia. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002 Oct;13(10):2508–16.

23. Pazour GJ, Dickert BL, Vucica Y, Seeley ES, Rosenbaum JL, Witman GB, et al. Chlamydomonas IFT88 and its mouse homologue, polycystic kidney disease gene tg737, are required for assembly of cilia and flagella. J Cell Biol. 2000 Oct 30;151(3):709–18.

24. Pazour GJ. Cilia.Pro database of ciliary proteins from vertebrates, Chlamydomonas, and Caenorhabditis. Mol Biol Cell. 2025 Sep 1;36(9):mr8.

25. Cole DG, Diener DR, Himelblau AL, Beech PL, Fuster JC, Rosenbaum JL. Chlamydomonas kinesin-II-dependent intraflagellar transport (IFT): IFT particles contain proteins required for ciliary assembly in Caenorhabditis elegans sensory neurons. J Cell Biol. 1998 May 18;141(4):993–1008.

26. Pazour GJ, Wilkerson CG, Witman GB. A dynein light chain is essential for the retrograde particle movement of intraflagellar transport (IFT). J Cell Biol. 1998 May 18;141(4):979–92.

27. Pazour GJ, Quarmby L, Smith AO, Desai PB, Schmidts M. Cilia in cystic kidney and other diseases. Cell Signal. 2020 May;69:109519.

28. Dordoni C, Zeni L, Toso D, Mazza C, Mescia F, Cortinovis R, et al. Monoallelic pathogenic IFT140 variants are a common cause of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease-spectrum phenotype. Clin Kidney J. 2024 Feb 15;17(2):sfae026.

29. Sang L, Miller JJ, Corbit KC, Giles RH, Brauer MJ, Otto EA, et al. Mapping the NPHP-JBTS-MKS protein network reveals ciliopathy disease genes and pathways. Cell. 2011 May 13;145(4):513–28.

30. Salomon R, Saunier S, Niaudet P. Nephronophthisis. Pediatr Nephrol. 2009 Dec;24(12):2333–44.

31. Hildebrandt F, Zhou W. Nephronophthisis-associated ciliopathies. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007 Jun;18(6):1855–71.

32. Collard E, Byrne C, Georgiou M, Michaelides M, Dixit A. Joubert syndrome diagnosed renally late. Clin Kidney J. 2020 Mar 12;14(3):1017–9.

33. Aggarwal HK, Jain D, Yadav S, Kaverappa V, Gupta A. Senior-loken syndrome with rare manifestations: a case report. Eurasian J Med. 2013 Jun;45(2):128–31.

34. Derderian C, Canales GI, Reiter JF. Seriously cilia: A tiny organelle illuminates evolution, disease, and intercellular communication. Dev Cell. 2023 Aug 7;58(15):1333–49.

35. Quatredeniers M, Bienaimé F, Ferri G, Isnard P, Porée E, Billot K, et al. The renal inflammatory network of nephronophthisis. Hum Mol Genet. 2022 Jul 7;31(13):2121–36.

36. Garcia H, Serafin AS, Silbermann F, Porée E, Viau A, Mahaut C, et al. Agonists of prostaglandin E2 receptors as potential first in class treatment for nephronophthisis and related ciliopathies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022 May 3;119(18):e2115960119.

37. Qian F, Watnick TJ, Onuchic LF, Germino GG. The molecular basis of focal cyst formation in human autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease type I. Cell. 1996 Dec 13;87(6):979–87.

38. Tan AY, Zhang T, Michaeel A, Blumenfeld J, Liu G, Zhang W, et al. Somatic Mutations in Renal Cyst Epithelium in Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018 Aug;29(8):2139–56.

39. Zhang Z, Bai H, Blumenfeld J, Ramnauth AB, Barash I, Prince M, et al. Detection of PKD1 and PKD2 Somatic Variants in Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Cyst Epithelial Cells by Whole-Genome Sequencing. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021 Dec 1;32(12):3114–29.

40. Stroope A, Radtke B, Huang B, Masyuk T, Torres V, Ritman E, et al. Hepato-renal pathology in pkd2ws25/- mice, an animal model of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Am J Pathol. 2010 Mar;176(3):1282–91.

41. Wu G, Markowitz GS, Li L, D'Agati VD, Factor SM, Geng L, et al. Cardiac defects and renal failure in mice with targeted mutations in Pkd2. Nat Genet. 2000 Jan;24(1):75–8.

42. Piontek K, Menezes LF, Garcia-Gonzalez MA, Huso DL, Germino GG. A critical developmental switch defines the kinetics of kidney cyst formation after loss of Pkd1. Nat Med. 2007 Dec;13(12):1490–5.

43. Takakura A, Contrino L, Beck AW, Zhou J. Pkd1 inactivation induced in adulthood produces focal cystic disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008 Dec;19(12):2351–63.

44. Takakura A, Contrino L, Zhou X, Bonventre JV, Sun Y, Humphreys BD, et al. Renal injury is a third hit promoting rapid development of adult polycystic kidney disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2009 Jul 15;18(14):2523–31.

45. Formica C, Peters DJM. Molecular pathways involved in injury-repair and ADPKD progression. Cell Signal. 2020 Aug;72:109648.

46. Lantinga-van Leeuwen IS, Dauwerse JG, Baelde HJ, Leonhard WN, van de Wal A, et al. Lowering of Pkd1 expression is sufficient to cause polycystic kidney disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2004 Dec 15;13(24):3069–77.

47. Hopp K, Ward CJ, Hommerding CJ, Nasr SH, Tuan HF, Gainullin VG, et al. Functional polycystin-1 dosage governs autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease severity. J Clin Invest. 2012 Nov;122(11):4257–73.

48. Ward CJ, Turley H, Ong AC, Comley M, Biddolph S, Chetty R, et al. Polycystin, the polycystic kidney disease 1 protein, is expressed by epithelial cells in fetal, adult, and polycystic kidney. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996 Feb 20;93(4):1524–8.

49. Wu G, Mochizuki T, Le TC, Cai Y, Hayashi T, Reynolds DM, et al. Molecular cloning, cDNA sequence analysis, and chromosomal localization of mouse Pkd2. Genomics. 1997 Oct 1;45(1):220–3.

50. Ong AC, Harris PC, Biddolph S, Bowker C, Ward CJ. Characterisation and expression of the PKD-1 protein, polycystin, in renal and extrarenal tissues. Kidney Int. 1999 May 18;55(5):2091–116.

51. Cai Y, Maeda Y, Cedzich A, Torres VE, Wu G, Hayashi T, et al. Identification and characterization of polycystin-2, the PKD2 gene product. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(40):28557–65.

52. Su Q, Hu F, Ge X, Lei J, Yu S, Wang T, et al. Structure of the human PKD1-PKD2 complex. Science. 2018 Sep 7;361(6406):eaat9819.

53. Praetorius HA, Spring KR. Bending the MDCK cell primary cilium increases intracellular calcium. J Membr Biol. 2001 Nov 1;184(1):71–9.

54. Nauli SM, Alenghat FJ, Luo Y, Williams E, Vassilev P, Li X, et al. Polycystins 1 and 2 mediate mechanosensation in the primary cilium of kidney cells. Nat Genet. 2003 Feb;33(2):129–37.

55. Rydholm S, Zwartz G, Kowalewski JM, Kamali-Zare P, Frisk T, Brismar H. Mechanical properties of primary cilia regulate the response to fluid flow. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2010 May;298(5):F1096–102.

56. Rohatgi R, Battini L, Kim P, Israeli S, Wilson PD, Gusella GL, et al. Mechanoregulation of intracellular Ca2+ in human autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease cyst-lining renal epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008 April;294(4):F890–9.

57. Xu C, Shmukler BE, Nishimura K, Kaczmarek E, Rossetti S, Harris PC, et al. Attenuated, flow-induced ATP release contributes to absence of flow-sensitive, purinergic Cai2+ signaling in human ADPKD cyst epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2009 Jun;296(6):F1464–76.

58. Delling M, DeCaen PG, Doerner JF, Febvay S, Clapham DE. Primary cilia are specialized calcium signalling organelles. Nature. 2013 Dec 12;504(7479):311–4.

59. Delling M, Indzhykulian AA, Liu X, Li Y, Xie T, Corey DP, et al. Primary cilia are not calcium-responsive mechanosensors. Nature. 2016 Mar 31;531(7596):656–60.

60. Revell DZ, Yoder BK. Intravital visualization of the primary cilium, tubule flow, and innate immune cells in the kidney utilizing an abdominal window imaging approach. Methods Cell Biol. 2019;154:67–83.

61. Kim S, Nie H, Nesin V, Tran U, Outeda P, Bai CX, et al. The polycystin complex mediates Wnt/Ca(2+) signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2016 Jul;18(7):752–64.

62. Ma M, Tian X, Igarashi P, Pazour GJ, Somlo S. Loss of cilia suppresses cyst growth in genetic models of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nat Genet. 2013 Sep;45(9):1004–12.

63. Liu X, Tang J, Chen XZ. Role of PKD2 in the endoplasmic reticulum calcium homeostasis. Front Physiol. 2022;13:962571.

64. Walker RV, Keynton JL, Grimes DT, Sreekumar V, Williams DJ, Esapa C, et al. Ciliary exclusion of Polycystin-2 promotes kidney cystogenesis in an autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease model. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):4072.

65. Ha K, Loeb GB, Park M, Gupta M, Akiyama Y, Argiris J, et al. ADPKD-Causing Missense Variants in Polycystin-1 Disrupt Cell Surface Localization or Polycystin Channel Function. BioRxiv [Preprint]. 2024 Dec 3:2023.12.04.570035.

66. Calvet JP. The Role of Calcium and Cyclic AMP in PKD. In: Li X, editor. Polycystic Kidney Disease [Internet]. Brisbane (AU): Codon Publications; 2015 Nov.

67. Yamaguchi T, Pelling JC, Ramaswamy NT, Eppler JW, Wallace DP, Nagao S, et al. cAMP stimulates the in vitro proliferation of renal cyst epithelial cells by activating the extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway. Kidney Int. 2000 Apr;57(4):1460–71.

68. Belibi FA, Reif G, Wallace DP, Yamaguchi T, Olsen L, Li H, et al. Cyclic AMP promotes growth and secretion in human polycystic kidney epithelial cells. Kidney Int. 2004 Sep;66(3):964–73.

69. Mehta YR, Lewis SA, Leo KT, Chen L, Park E, Raghuram V, et al. "ADPKD-omics": determinants of cyclic AMP levels in renal epithelial cells. Kidney Int. 2022 Jan;101(1):47–62

70. Vuolo L, Herrera A, Torroba B, Menendez A, Pons S. Ciliary adenylyl cyclases control the Hedgehog pathway. J Cell Sci. 2015 Aug 1;128(15):2928–37.

71. Rees S, Kittikulsuth W, Roos K, Strait KA, Van Hoek A, Kohan DE. Adenylyl cyclase 6 deficiency ameliorates polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014 Feb;25(2):232–7.

72. Spirli C, Mariotti V, Villani A, Fabris L, Fiorotto R, Strazzabosco M. Adenylyl cyclase 5 links changes in calcium homeostasis to cAMP-dependent cyst growth in polycystic liver disease. J Hepatol. 2017 Mar;66(3):571–80.

73. Reif GA, Yamaguchi T, Nivens E, Fujiki H, Pinto CS, Wallace DP. Tolvaptan inhibits ERK-dependent cell proliferation, Cl⁻ secretion, and in vitro cyst growth of human ADPKD cells stimulated by vasopressin. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2011 Nov;301(5):F1005–13.

74. Hansen JN, Kaiser F, Leyendecker P, Stuven B, Krause JH, Derakhshandeh F, et al. A cAMP signalosome in primary cilia drives gene expression and kidney cyst formation. EMBO Rep. 2022 Aug 3;23(8):e54315.

75. Pearce D, Soundararajan R, Trimpert C, Kashlan OB, Deen PM, Kohan DE. Collecting duct principal cell transport processes and their regulation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015 Jan 7;10(1):135–46.

76. Alonso G, Galibert E, Boulay V, Guillou A, Jean A, Compan V, et al. Sustained elevated levels of circulating vasopressin selectively stimulate the proliferation of kidney tubular cells via the activation of V2 receptors. Endocrinology. 2009 Jan;150(1):239–50.

77. Van Gastel MDA, Torres VE. Polycystic Kidney Disease and the Vasopressin Pathway. Ann Nutr Metab. 2017;70 Suppl 1:43–50.

78. Mutig K, Paliege A, Kahl T, Jons T, Muller-Esterl W, Bachmann S. Vasopressin V2 receptor expression along rat, mouse, and human renal epithelia with focus on TAL. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007 Oct;293(4):F1166–77.

79. Wang X, Wu Y, Ward CJ, Harris PC, Torres VE. Vasopressin directly regulates cyst growth in polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008 Jan;19(1):102–8.

80. Zittema D, Casteleijn NF, Bakker SJ, Boesten LS, Duit AA, Franssen CF, et al. Urine Concentrating Capacity, Vasopressin and Copeptin in ADPKD and IgA Nephropathy Patients with Renal Impairment. PLoS One. 2017 Jan 12;12(1):e0169263.

81. Wang X, Gattone V, 2nd, Harris PC, Torres VE. Effectiveness of vasopressin V2 receptor antagonists OPC-31260 and OPC-41061 on polycystic kidney disease development in the PCK rat. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005 Apr;16(4):846–51.

82. Torres VE, Wang X, Qian Q, Somlo S, Harris PC, Gattone VH 2nd. Effective treatment of an orthologous model of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nat Med. 2004 Apr;10(4):363–4.

83. Gattone VH, 2nd, Wang X, Harris PC, Torres VE. Inhibition of renal cystic disease development and progression by a vasopressin V2 receptor antagonist. Nat Med. 2003 Oct;9(10):1323–6.

84. Torres VE, Chapman AB, Devuyst O, Gansevoort RT, Perrone RD, Koch G, et al. Tolvaptan in Later-Stage Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. N Engl J Med. 2017 Nov 16;377(20):1930–42.

85. Torres VE, Chapman AB, Devuyst O, Gansevoort RT, Perrone RD, Dandurand A, et al. Multicenter, open-label, extension trial to evaluate the long-term efficacy and safety of early versus delayed treatment with tolvaptan in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: the TEMPO 4:4 Trial. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2018 Mar 1;33(3):477–89.

86. Zafar I, Ravichandran K, Belibi FA, Doctor RB, Edelstein CL. Sirolimus attenuates disease progression in an orthologous mouse model of human autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2010 Oct;78(8):754–61.

87. Kim HJ, Edelstein CL. Mammalian target of rapamycin inhibition in polycystic kidney disease: From bench to bedside. Kidney Res Clin Pract. 2012 Sep;31(3):132–8.

88. Shillingford JM, Piontek KB, Germino GG, Weimbs T. Rapamycin ameliorates PKD resulting from conditional inactivation of Pkd1. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010 Mar;21(3):489–97.

89. Li A, Fan S, Xu Y, Meng J, Shen X, Mao J, et al. Rapamycin treatment dose-dependently improves the cystic kidney in a new ADPKD mouse model via the mTORC1 and cell-cycle-associated CDK1/cyclin axis. J Cell Mol Med. 2017 Aug;21(8):1619–35.

90. Perico N, Antiga L, Caroli A, Ruggenenti P, Fasolini G, Cafaro M, et al. Sirolimus therapy to halt the progression of ADPKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010 Jun;21(6):1031–40.

91. Serra AL, Poster D, Kistler AD, Krauer F, Raina S, Young J, et al. Sirolimus and kidney growth in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2010 Aug 26;363(9):820–9.

92. Braun WE, Schold JD, Stephany BR, Spirko RA, Herts BR. Low-dose rapamycin (sirolimus) effects in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: an open-label randomized controlled pilot study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014 May;9(5):881–8.

93. Walz G, Budde K, Mannaa M, Nurnberger J, Wanner C, Sommerer C, et al. Everolimus in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2010 Aug 26;363(9):830–40.

94. Williams RM, Shah J, Ng BD, Minton DR, Gudas LJ, Park CY, et al. Mesoscale nanoparticles selectively target the renal proximal tubule epithelium. Nano Lett. 2015 Apr 8;15(4):2358–64.

95. Yamaguchi S, Sedaka R, Kapadia C, Huang J, Hsu JS, Berryhill TF, et al. Rapamycin-encapsulated nanoparticle delivery in polycystic kidney disease mice. Sci Rep. 2024 Jul 2;14(1):15140.

96. Liu F, Zhuang S. Role of Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Signaling in Renal Fibrosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2016 Jun 20;17(5):972.

97. Buhl EM, Djudjaj S, Klinkhammer BM, Ermert K, Puelles VG, Lindenmeyer MT, et al. Dysregulated mesenchymal PDGFR-β drives kidney fibrosis. EMBO Mol Med. 2020 Mar 6;12(3):e11021.

98. Feng L, Li W, Chao Y, Huan Q, Lu F, Yi W, et al. Synergistic Inhibition of Renal Fibrosis by Nintedanib and Gefitinib in a Murine Model of Obstructive Nephropathy. Kidney Dis (Basel). 2021 Jan;7(1):34–49.

99. Liu N, Guo JK, Pang M, Tolbert E, Ponnusamy M, Gong R, et al. Genetic or pharmacologic blockade of EGFR inhibits renal fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012 May;23(5):854–67.

100. Tao Y, Kim J, Yin Y, Zafar I, Falk S, He Z, et al. VEGF receptor inhibition slows the progression of polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2007 Dec;72(11):1358–66.

101. Qin S, Taglienti M, Nauli SM, Contrino L, Takakura A, Zhou J, et al. Failure to ubiquitinate c-Met leads to hyperactivation of mTOR signaling in a mouse model of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(10):3617–28.

102. Jamadar A, Suma SM, Mathew S, Fields TA, Wallace DP, Calvet JP, et al. The tyrosine-kinase inhibitor Nintedanib ameliorates autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12(10):947.

103. Sen B, Saigal B, Parikh N, Gallick G, Johnson FM. Sustained Src inhibition results in signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) activation and cancer cell survival via altered Janus-activated kinase-STAT3 binding. Cancer Res. 2009;69(5):1958–65.

104. van Oijen MG, Rijksen G, ten Broek FW, Slootweg PJ. Overexpression of c-Src in areas of hyperproliferation in head and neck cancer, premalignant lesions and benign mucosal disorders. J Oral Pathol Med. 1998;27(4):147–52.

105. Marcotte R, Smith HW, Sanguin-Gendreau V, McDonough RV, Muller WJ. Mammary epithelial-specific disruption of c-Src impairs cell cycle progression and tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(8):2808–13.

106. Schmitt JM, Stork PJ. PKA phosphorylation of Src mediates cAMP's inhibition of cell growth via Rap1. Mol Cell. 2002;9(1):85–94.

107. Sweeney WE, Jr., von Vigier RO, Frost P, Avner ED. Src inhibition ameliorates polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19(7):1331–41.

108. Elliott J, Zheleznova NN, Wilson PD. c-Src inactivation reduces renal epithelial cell-matrix adhesion, proliferation, and cyst formation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2011;301(2):C522–9.

109. Tesar V, Ciechanowski K, Pei Y, Barash I, Shannon M, Li R, et al. Bosutinib versus Placebo for Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28(11):3404–13.

110. Sweeney WE, Frost P, Avner ED. Tesevatinib ameliorates progression of polycystic kidney disease in rodent models of autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease. World J Nephrol. 2017;6(4):188–200.

111. Hanaoka K, Guggino WB. cAMP regulates cell proliferation and cyst formation in autosomal polycystic kidney disease cells. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11(7):1179–87.

112. Wallace DP, Grantham JJ, Sullivan LP. Chloride and fluid secretion by cultured human polycystic kidney cells. Kidney Int. 1996;50(4):1327–36.

113. Cabrita I, Kraus A, Scholz JK, Skoczynski K, Schreiber R, Kunzelmann K, et al. Cyst growth in ADPKD is prevented by pharmacological and genetic inhibition of TMEM16A in vivo. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):4320.

114. Lebeau C, Hanaoka K, Moore-Hoon ML, Guggino WB, Beauwens R, Devuyst O. Basolateral chloride transporters in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Pflugers Arch. 2002 Sep;444(6):722–31.

115. Rajagopal M, Wallace DP. Chloride secretion by renal collecting ducts. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2015;24(5):444–9.

116. Brill SR, Ross KE, Davidow CJ, Ye M, Grantham JJ, Caplan MJ. Immunolocalization of ion transport proteins in human autosomal dominant polycystic kidney epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(19):10206–11.

117. Xu N, Glockner JF, Rossetti S, Babovich-Vuksanovic D, Harris PC, Torres VE. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease coexisting with cystic fibrosis. J Nephrol. 2006;19(4):529–34.

118. O'Sullivan DA, Torres VE, Gabow PA, Thibodeau SN, King BF, Bergstralh EJ. Cystic fibrosis and the phenotypic expression of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998;32(6):976–83

119. Magenheimer BS, St John PL, Isom KS, Abrahamson DR, De Lisle RC, Wallace DP, et al. Early embryonic renal tubules of wild-type and polycystic kidney disease kidneys respond to cAMP stimulation with cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator/Na(+),K(+),2Cl(-) Co-transporter-dependent cystic dilation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17(12):3424–37.

120. Talbi K, Cabrita I, Kraus A, Hofmann S, Skoczynski K, Kunzelmann K, et al. The chloride channel CFTR is not required for cyst growth in an ADPKD mouse model. FASEB J. 2021;35(10):e21897.

121. de Wilde G, Gees M, Musch S, Verdonck K, Jans M, Wesse AS, et al. Identification of GLPG/ABBV-2737, a Novel Class of Corrector, Which Exerts Functional Synergy With Other CFTR Modulators. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:514.

122. Dumont V, Meurisse S, Verdonck K, Salgues V, Robert T, Anquetil F, et al. GLPG2737, a CFTR Inhibitor, Prevents Cyst Growth in Preclinical Models of Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. Am J Nephrol. 2025:1–10.

123. van Koningsbruggen-Rietschel S, Conrath K, Fischer R, Sutharsan S, Kempa A, Gleiber W, et al. GLPG2737 in lumacaftor/ivacaftor-treated CF subjects homozygous for the F508del mutation: A randomized phase 2A trial (PELICAN). J Cyst Fibros. 2020;19(2):292–8.

124. Ruppersburg CC, Hartzell HC. The Ca2+-activated Cl- channel ANO1/TMEM16A regulates primary ciliogenesis. Mol Biol Cell. 2014;25(11):1793–807.

125. Hanaoka K, Devuyst O, Schwiebert EM, Wilson PD, Guggino WB. A role for CFTR in human autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Am J Physiol. 1996;270(1 Pt 1):C389–99.

126. Lopes-Pacheco M, Boinot C, Sabirzhanova I, Morales MM, Guggino WB, Cebotaru L. Combination of Correctors Rescue DeltaF508-CFTR by Reducing Its Association with Hsp40 and Hsp27. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(42):25636–45.

127. Rowe SM, Verkman AS. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator correctors and potentiators. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2013;3(7).

128. Yanda MK, Liu Q, Cebotaru L. A potential strategy for reducing cysts in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease with a CFTR corrector. J Biol Chem. 2018;293(29):11513–26.

129. Seeger-Nukpezah T, Proia DA, Egleston BL, Nikonova AS, Kent T, Cai KQ, et al. Inhibiting the HSP90 chaperone slows cyst growth in a mouse model of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(31):12786–91.

130. Van Goor F, Hadida S, Grootenhuis PD, Burton B, Stack JH, Straley KS, et al. Correction of the F508del-CFTR protein processing defect in vitro by the investigational drug VX-809. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(46):18843–8.

131. Yanda MK, Tomar V, Cebotaru L. Therapeutic Potential for CFTR Correctors in Autosomal Recessive Polycystic Kidney Disease. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;12(5):1517–29.

132. Van Goor F, Straley KS, Cao D, Gonzalez J, Hadida S, Hazlewood A, et al. Rescue of DeltaF508-CFTR trafficking and gating in human cystic fibrosis airway primary cultures by small molecules. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;290(6):L1117–30.

133. Kim Chiaw P, Wellhauser L, Huan LJ, Ramjeesingh M, Bear CE. A chemical corrector modifies the channel function of F508del-CFTR. Mol Pharmacol. 2010;78(3):411–8.

134. Nikonova AS, Deneka AY, Kiseleva AA, Korobeynikov V, Gaponova A, Serebriiskii IG, et al. Ganetespib limits ciliation and cystogenesis in autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD). FASEB J. 2018;32(5):2735–46.

135. Lin F, Hiesberger T, Cordes K, Sinclair AM, Goldstein LS, Somlo S, et al. Kidney-specific inactivation of the KIF3A subunit of kinesin-II inhibits renal ciliogenesis and produces polycystic kidney disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(9):5286–91.

136. Patel V, Williams D, Hajarnis S, Hunter R, Pontoglio M, Somlo S, et al. miR-17~92 miRNA cluster promotes kidney cyst growth in polycystic kidney disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(26):10765–70.

137. Lakhia R, Hajarnis S, Williams D, Aboudehen K, Yheskel M, Xing C, et al. MicroRNA-21 Aggravates Cyst Growth in a Model of Polycystic Kidney Disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27(8):2319–30.

138. Lee EC, Valencia T, Allerson C, Schairer A, Flaten A, Yheskel M, et al. Discovery and preclinical evaluation of anti-miR-17 oligonucleotide RGLS4326 for the treatment of polycystic kidney disease. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):4148.

139. Yheskel M, Lakhia R, Cobo-Stark P, Flaten A, Patel V. Anti-microRNA screen uncovers miR-17 family within miR-17~92 cluster as the primary driver of kidney cyst growth. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):1920.

140. Hajarnis S, Lakhia R, Yheskel M, Williams D, Sorourian M, Liu X, et al. microRNA-17 family promotes polycystic kidney disease progression through modulation of mitochondrial metabolism. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14395.

141. Fedeles BI, Bhardwaj R, Ishikawa Y, Khumsubdee S, Krappitz M, Gubina N, et al. A synthetic agent ameliorates polycystic kidney disease by promoting apoptosis of cystic cells through increased oxidative stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2024;121(4):e2317344121.

142. Schimmel MF, Bourgeois BC, Spindt AK, Patel SA, Chin T, Cornick GE, et al. Development of a cyst-targeted therapy for polycystic kidney disease using an antagonistic dimeric IgA monoclonal antibody against cMET. Cell Rep Med. 2025:102335.

143. Bardia A, Hurvitz SA, Tolaney SM, Loirat D, Punie K, Oliveira M, et al. Sacituzumab Govitecan in Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(16):1529–41.

144. Shvartsur A, Bonavida B. Trop2 and its overexpression in cancers: regulation and clinical/therapeutic implications. Genes Cancer. 2015;6(3-4):84–105.

145. Ruder S, Martinez J, Palmer J, Arham AB, Tagawa ST. Antibody-drug conjugates in urothelial carcinoma: current status and future. Curr Opin Urol. 2025;35(3):292–300.

146. Liu X, Ma L, Li J, Sun L, Yang Y, Liu T, et al. Trop2-targeted therapies in solid tumors: advances and future directions. Theranostics. 2024;14(9):3674–92.

147. Tong Y, Fan X, Liu H, Liang T. Advances in Trop-2 targeted antibody-drug conjugates for breast cancer: mechanisms, clinical applications, and future directions. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1495675.

148. Smith AO, Frantz WT, Preval KM, Edwards YJK, Ceol CJ, Jonassen JA, et al. The Tumor-Associated Calcium Signal Transducer 2 (TACSTD2) oncogene is upregulated in cystic epithelial cells revealing a potential new target for polycystic kidney disease. PLoS Genet. 2024;20(12):e1011510.