Abstract

The introduction of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) targeting cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) and later programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) or its ligand (PD-L1) marked a turning point in cancer therapy. These agents validated the principle that durable tumor control can be achieved by releasing inhibitory pathways that restrain antitumor T cell responses. Long-term survival benefits in melanoma, non-small cell lung cancer, and other malignancies have established immunotherapy as a defining development in oncology. However, long-term clinical benefits remain confined to a minority of patients, and resistance or relapse is common in the remaining patients. The mechanisms underlying this limited efficacy include inadequate T cell infiltration, tumor-intrinsic defects in antigen presentation, compensatory upregulation of alternative checkpoints, and an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME). In addition, immune-related toxicities, particularly those associated with CTLA-4 blockade, restrict the broader use of these agents. To overcome these barriers, attention has shifted toward next-generation checkpoint pathways in cancer therapy. Inhibitory receptors, such as LAG-3, TIGIT, TIM-3, and VISTA, along with innate checkpoints, including CD47-SIRPα, NKG2A, and Siglec-15, are emerging as promising targets. Simultaneously, strategies to enhance co-stimulatory signaling through OX40, 4-1BB, ICOS, GITR, and CD40 aim to overcome T cell exhaustion and broaden immune activation have been developed. The approval of relatlimab, an anti-LAG-3 antibody, in combination with nivolumab, provides clinical proof-of-concept, while many agents directed at additional pathways remain in early- and late-phase trials. This review summarizes the current knowledge of next-generation checkpoint biology and development, highlights resistance mechanisms and biomarker-driven patient selection, and considers future approaches, including multispecific antibodies, engineered cytokines, and precision immunotherapy strategies.

Keywords

Artificial intelligence, Biomarkers, Cancer immunotherapy, Immune checkpoint inhibitors, Resistance mechanisms

Background

The approval of the first ICI, the anti-CTLA-4 antibody ipilimumab, in 2011, marked a major turning point in cancer therapy. Ipilimumab demonstrated for the first time that durable tumor regression and long-term survival could be achieved through immune system modulation in patients with advanced melanoma [1]. This finding validates the concept that T cell inhibition, long recognized as a barrier to immune-mediated tumor control, can be therapeutically targeted. Shortly thereafter, antibodies against PD-1 and its ligand PD-L1 produced improved outcomes with a more favorable toxicity profile, rapidly expanding immunotherapy into multiple cancer types, including non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), renal cell carcinoma, and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma [2–5]. Together, CTLA-4 and PD-1/PD-L1 blockade defined the first generation of cancer immunotherapy and established ICIs as the cornerstone of modern cancer treatment.

Despite these achievements, the sustained benefits are restricted to a minority of patients. Follow-up studies have shown a survival plateau, but most patients eventually relapse [6–8]. Both, primary resistance, characterized by non-inflamed or “cold” tumors lacking T cell infiltration, and acquired resistance, reflecting tumor evolution under immune pressure, contribute to limited efficacy. Expanding on this simplified “cold” versus “hot” tumor framework, recent studies emphasize the concept of “immune contexture,” which highlights the density, composition, spatial distribution, and functional state of immune infiltrates as critical determinants of response to checkpoint blockade [9]. Tumor-intrinsic mechanisms, such as defects in antigen presentation (e.g., β2-microglobulin mutations) and interferon-γ signaling (e.g., JAK1/2 alterations), along with the adaptive upregulation of alternative inhibitory receptors, also undermine checkpoint efficacy [6,10,11]. In parallel, an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME), encompassing regulatory T cells, myeloid-derived suppressor cells, tumor-associated macrophages, and adenosine metabolism, further constrains antitumor immunity [12,13]. Toxicity poses an important barrier and limits the broader clinical application of ICIs. Immune-related adverse events (irAEs) are common, affect multiple organ systems, and are typically more frequent and severe with CTLA-4 blockade than with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors [14–16]. Importantly, these irAEs represent a class effect of immune activation rather than off-target toxicity, reflecting the same immune mechanisms that mediate tumor control.

Combination therapy, while more effective in some settings, carries a significantly higher risk of irAEs and requires careful clinical management [17,18]. These efficacy and safety limitations emphasize the need for additional therapeutic strategies to improve treatment outcomes. This challenge has driven interest in next-generation immune checkpoint inhibitors. Inhibitory receptors, such as LAG-3, TIGIT, TIM-3, and VISTA, contribute to T cell dysfunction and immune escape, whereas innate regulators, such as CD47–SIRPα, NKG2A, and Siglec-15, modulate myeloid and natural killer (NK) cell activity. Simultaneously, co-stimulatory pathways, including OX40, 4-1BB, ICOS, GITR, and CD40, are being targeted to restore function in exhausted T cells and expand antitumor responses. The approval of relatlimab, an anti–LAG-3 antibody, in combination with nivolumab for melanoma in 2022, provided the first clinical validation of this next wave of checkpoint modulation [19, 20].

In this review, we summarize the current knowledge of next-generation checkpoint biology and therapeutic development, highlight the mechanisms of resistance that limit efficacy, and discuss biomarker-guided approaches for patient selection. We also examined rational combination strategies and future innovations, including multispecific antibodies, engineered cytokines, and precision immunotherapy frameworks, which are likely to drive the next phase of cancer treatment.

Immune Regulatory Mechanisms of Next-Generation Checkpoint Inhibitors

Building on the foundational success of anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapies, the field of immune checkpoint inhibition has evolved beyond its initial targets. This evolution is driven by the limited proportion of patients achieving sustained responses and the frequent emergence of resistance mechanisms, prompting deeper investigations into the broader network of immune regulatory pathways that govern anti-tumor immunity. Current efforts focus on two major strategies: targeting alternative inhibitory checkpoints that regulate adaptive immunity, including T cell inhibitory molecules such as LAG-3, TIGIT, TIM-3, VISTA, and BTLA, and disrupting innate and myeloid checkpoints, such as the CD47–SIRPα axis, NKG2A, and Siglec-15 [21,22]. A detailed examination of the molecular mechanisms underlying these pathways provides a foundation for identifying the most promising next-generation targets.

Lymphocyte-activation gene 3 (LAG-3)

LAG-3 (CD223) was the earliest next-generation checkpoint to be described and remains one of the most extensively studied inhibitory receptors apart from CTLA-4 and PD-1 [23]. It is expressed on activated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, regulatory T cells (Tregs), and natural killer (NK) cells [23]. Functionally, it attenuates T cell activation and proliferation through multiple ligand interactions [23]. Its canonical ligand is the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II, which binds with higher affinity than CD4, thereby interfering with T cell receptor (TCR) signaling and limiting effector function [24]. In addition to MHC II, non-canonical ligands such as fibrinogen-like protein 1 (FGL1) [25] and galectin-3 [26] contribute to LAG-3 mediated immunoregulation within the tumor microenvironment (TME), expanding its role outside of classical antigen presentation pathways.

Together, these interactions define LAG-3 as a distinct inhibitory pathway and provide a clear rationale for therapeutic targeting, particularly in the context of PD-1 blockade therapy. LAG-3 is frequently co-expressed with PD-1 on exhausted CD8+ T cells, and simultaneous signaling through both receptors consolidates T cell dysfunction [27, 28]. Consistent with this, preclinical studies have demonstrated that dual blockade of LAG-3 and PD-1 restores effector activity and cytokine production more effectively than inhibition of either pathway alone, establishing a strong mechanistic foundation for co-targeting strategies [27,28].

T cell immunoreceptor with Ig and ITIM domains (TIGIT)

TIGIT, a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily, acts as a dominant inhibitory receptor that restrains antitumor immunity by simultaneously suppressing CD8+ T cell function, enhancing Treg activity, and suppressing NK-cell cytotoxicity [29–31]. Its principal ligands are poliovirus receptor (PVR, CD155) and nectin-2 (CD112), which are frequently upregulated in tumor cells and antigen-presenting cells. TIGIT binds these ligands with a higher affinity than the co-stimulatory receptor CD226, thereby outcompeting activating signals and skewing the immune balance toward inhibition [29,32]. In addition to this competitive mechanism, TIGIT delivers intrinsic inhibitory signaling through its ITIM and ITT-like motifs, recruiting phosphatases such as SHIP1 to suppress the PI3K and MAPK pathways [33]. Engagement of TIGIT on Tregs enhances their suppressive capacity, whereas binding on dendritic cells (DCs) promotes a tolerogenic phenotype with increased IL-10 production [29]. Recent studies have further shown that TIGIT contributes to the metabolic dysfunction of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes by limiting glycolysis and promoting a terminally exhausted state [34–36]. Collectively, these effects establish a multilayered immunosuppressive program that is not fully compensated by other checkpoints. Preclinical studies have validated this rationale, showing that TIGIT blockade restores CD8+ T cell activity, reactivates NK cell function, and synergizes with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibition across multiple tumor models [31]. These findings position TIGIT as a compelling therapeutic target with unique potential to broaden the efficacy of checkpoint blockade therapy by bridging adaptive and innate immunity.

T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain-containing protein 3 (TIM-3)

Unlike other inhibitory checkpoints defined by a single dominant ligand, TIM-3 functions as a versatile immune regulator, expressed on exhausted CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, Tregs, NK cells, and DCs, where it enforces immune dysfunction and tolerance through diverse ligand interactions [37,38]. Galectin-9 binding induces apoptosis or dysfunction of Th1 effector cells through the disruption of Bat3-mediated signaling [39]. Phosphatidylserine facilitates the recognition of apoptotic cells and suppresses T cell activity [40]. CEACAM1 stabilizes TIM-3 function and cooperatively enforces T cell exhaustion [41]. HMGB1 blocks nucleic acid sensing by DCs, limiting innate immune activation [42]. Functionally, TIM-3 signaling attenuates TCR activation, promotes terminal T cell exhaustion, and stabilizes Treg activity. On NK cells, TIM-3 ligation reduces cytotoxicity, whereas on DCs, it interferes with nucleic acid–driven activation, thereby suppressing both innate and adaptive immune responses [43]. Importantly, TIM-3 is frequently co-expressed with PD-1 on tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, marking a population of highly dysfunctional T cells associated with a poor prognosis [44]. These diverse mechanisms distinguish TIM-3 as a unique inhibitory pathway. Preclinical studies have shown that its blockade restores effector function, enhances cytokine production, and synergizes with PD-1 inhibition to overcome resistance across multiple tumor models [45,46].

V-domain Ig suppressor of T-cell activation (VISTA)

VISTA, also known as programmed death-1 homolog (PD-1H), is an inhibitory receptor of the B7 family that functions as both a ligand and receptor to reinforce immune suppression [47]. It is expressed on naïve CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, Tregs, and at particularly high levels on myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and tumor-associated macrophages [48,49]. Structurally, VISTA contains a single IgV domain and a cytoplasmic tail lacking canonical ITIM motifs but is capable of recruiting phosphatases to attenuate proximal TCR signaling [50]. Functionally, VISTA ligation suppresses T cell proliferation, cytokine production, and effector differentiation, while enhancing the suppressive activity of Tregs [48]. Within the tumor microenvironment, its high expression in infiltrating myeloid cells reinforces immunosuppressive niches [51]. A key feature is that VISTA expression is frequently upregulated following PD-1/PD-L1 blockade, implicating it in adaptive resistance mechanisms that limit first-generation immunotherapies [52]. This compensatory role makes VISTA a particularly attractive target for next-generation immunotherapeutic strategies. Supporting this rationale, preclinical studies in murine tumor models have shown that genetic deletion or antibody-mediated blockade of VISTA enhances CD8+ T cell activation, reduces myeloid suppressor activity, and delays tumor growth, with further efficacy when combined with PD-1 inhibition [53]. These findings establish VISTA as a mechanistically unique and clinically relevant checkpoint, providing a strong rationale for its development as a next-generation immunotherapy target.

B and T lymphocyte attenuator (BTLA)

BTLA (CD272) is an inhibitory receptor of the immunoglobulin superfamily expressed on naïve and activated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, B cells, and subsets of dendritic cells (DCs) [54]. Its principal ligand is the herpesvirus entry mediator (HVEM), a TNFR superfamily member that is broadly expressed on hematopoietic and non-hematopoietic cells. Engagement of BTLA with HVEM recruits SHP-1 and SHP-2 phosphatases through its cytoplasmic ITIM and ITSM motifs, thereby attenuating proximal TCR signaling and limiting cytokine production [55]. In addition to directly inhibiting effector T cells, BTLA–HVEM interactions contribute to immune homeostasis by reinforcing the regulatory pathways and preventing overactivation [56]. In the tumor microenvironment, BTLA expression on tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes correlates with an exhausted phenotype, suggesting cooperation with PD-1 and other checkpoints to consolidate T cell dysfunction [57]. Preclinical evidence indicates that blockade of the BTLA–HVEM axis enhances T cell proliferation and cytokine production and, in some models, synergizes with PD-1 inhibition to restore antitumor immunity [58]. Although its therapeutic development lags behind that of LAG-3, TIGIT, and TIM-3, the distinctive biology of BTLA highlights its potential as a complementary next-generation checkpoint target.

CD47–SIRPα axis

In addition to T cell–directed checkpoints, a growing body of work highlights innate and myeloid inhibitory pathways as critical regulators of tumor immune evasion. Among these, the CD47–SIRPα axis represents a prototypical innate checkpoint that suppresses macrophage-mediated clearance of tumor cells. CD47 is a ubiquitously expressed transmembrane glycoprotein, also known as an integrin-associated protein, that is frequently upregulated in malignant cells, where it functions as a canonical “don’t eat me” signal [59]. Its receptor, signal regulatory protein α (SIRPα), is expressed on myeloid cells, including macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs). Engagement of CD47 with SIRPα induces phosphorylation of immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motifs (ITIMs) in the SIRPα cytoplasmic domain, recruiting SHP-1 and SHP-2 phosphatases [60]. At this phagocytic synapse, the interplay between anti-phagocytic signals such as CD47 and pro-phagocytic cues like calreticulin ultimately determines whether tumor cells are engulfed or spared [61]. This cascade disrupts myosin-II assembly at the phagocytic synapse, thereby blocking the cytoskeletal rearrangements required for the engulfment of target cells [60]. Through these mechanisms, tumor cells exploit the CD47–SIRPα axis to evade innate immune surveillance. High CD47 expression has been documented in hematologic and solid malignancies, where it suppresses macrophage phagocytosis and simultaneously impairs dendritic cell cross-presentation and the priming of tumor-specific CD8+ T cells [62]. Thus, CD47 signaling establishes an immunosuppressive bottleneck that bridges innate evasion and downstream adaptive dysfunction. Preclinical studies have provided compelling evidence for therapeutic targeting: genetic deletion or antibody blockade of CD47 restores macrophage phagocytosis, enhances dendritic cell antigen presentation, and amplifies CD8+ T cell responses in multiple tumor models [62]. These findings firmly establish the CD47–SIRPα axis as a dominant innate immune checkpoint and provide a strong mechanistic rationale for prioritizing it in next-generation immunotherapy strategies.

NKG2A–HLA-E axis

The NKG2A–HLA-E pathway functions as a central inhibitory checkpoint at the interface between innate and adaptive immunity. NKG2A, a C-type lectin receptor, forms a heterodimer with CD94 and is predominantly expressed on NK cells and a subset of activated CD8+ T cells [63]. Its principal ligand, HLA-E, is a non-classical MHC class I molecule that presents peptides derived from the leader sequences of other HLA class I proteins. Tumor cells frequently upregulate HLA-E, thereby engaging NKG2A/CD94 and transmitting inhibitory signals that dampen cytotoxic lymphocyte activity [64]. Mechanistically, the engagement of NKG2A with HLA-E initiates inhibitory signaling via immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motifs (ITIMs) in the NKG2A cytoplasmic tail. These motifs recruit SHP-1 and SHP-2 phosphatases, suppressing downstream ERK and PI3K pathways, thereby attenuating cytotoxic lymphocyte activation [65]. In the tumor microenvironment, tumor-driven upregulation of HLA-E impairs NK-cell cytotoxicity and restricts CD8+ T cell effector responses [66]. Importantly, NKG2A is often co-expressed with PD-1 on exhausted CD8+ T cells, underscoring its cooperative role in sustaining immune dysfunction and providing a rationale for dual blockade approaches. Preclinical studies have shown that NKG2A blockade restores NK- and CD8+ T cell activity and enhances tumor control when combined with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibition [67]. NKG2A represents a distinctive checkpoint at the interface of innate and adaptive immunity, and its biology is naturally connected with other myeloid-focused targets, such as Siglec-15, which further reinforces tumor-associated immunosuppression.

Siglec-15

Siglec-15 is a member of the CD33-related sialic acid–binding immunoglobulin-like lectin (Siglec) family, expressed primarily on tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), and subsets of DCs [68]. Unlike classical inhibitory receptors with cytoplasmic ITIM motifs, Siglec-15 associates with the adaptor protein DAP12, which contains immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs (ITAMs) and recruits SYK family kinases [69]. Despite signaling through an activating adaptor, the net outcome of Siglec-15 engagement is the suppression of T cell proliferation and cytokine production, although the precise downstream inhibitory pathways remain undefined [68]. Functionally, Siglec-15 binds to sialylated glycans expressed on T cells and contributes to immune evasion by blunting effector responses within the tumor microenvironment. Importantly, tumor expression of Siglec-15 often occurs in a mutually exclusive pattern with PD-L1, suggesting that it represents a non-redundant checkpoint axis, particularly relevant in tumors resistant to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade [68]. Preclinical models have demonstrated that antibody-mediated blockade of Siglec-15 restores T cell function and reduces tumor growth, providing a strong mechanistic rationale for its therapeutic targeting. Together, these features establish Siglec-15 as a distinctive next-generation checkpoint, operating primarily within the myeloid compartment and complementing adaptive immune checkpoints such as PD-1 and LAG-3.

Co-stimulatory Pathway Enhancement

While inhibitory checkpoints restrain immune activation, co-stimulatory receptors provide complementary signals required to sustain effective T cell and antigen-presenting cell (APC) responses. Members of the tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) superfamily, such as 4-1BB (CD137), OX40 (CD134), ICOS, GITR, and CD40, act as “signal 2” molecules that reinforce T cell proliferation, survival, cytokine production, and memory differentiation [70]. These receptors are typically induced following TCR engagement, creating a temporal checkpoint that balances activation and immune regulation. In addition to promoting effector T cell function, several of these pathways modulate Treg stability, NK-cell cytotoxicity, and DC maturation, thereby broadening their immunological impact [71]. Mechanistic insights into these pathways have guided the development of agonist antibodies aimed at amplifying antitumor immunity. Although early efforts have highlighted challenges related to receptor clustering and systemic cytokine activation, continued optimization through bispecific and Fc-engineered formats has advanced the field toward safer and more effective designs. The following subsections summarize the biology and therapeutic progress of key co-stimulatory receptors currently under investigation.

4-1BB (CD137)

4-1BB (CD137) is an inducible co-stimulatory receptor of the TNFR superfamily, that is expressed on activated CD8+ and CD4+ T cells, NK cells, DCs, and macrophages [72]. Its ligand, 4-1BBL, is primarily expressed on activated APCs, and the engagement of this receptor–ligand pair delivers potent secondary signals that amplify immune activation. 4-1BB signaling recruits TNFR-associated factors TRAF1 and TRAF2, which activate the NF-κB, MAPK, and PI3K–AKT cascades [70]. These downstream pathways drive T cell proliferation, survival, and effector differentiation, increase IFN-γ secretion, promote the expansion of long-lived memory CD8+ T cells, and enhance NK-cell cytotoxicity. 4-1BB engagement can also modulate dendritic cells and macrophages, reinforcing their capacity to support antitumor immunity [73]. Preclinical studies have shown that agonistic 4-1BB antibodies induce potent tumor regression in murine models, mediated by robust CD8+ T cell expansion and NK cell activity [73]. These findings establish 4-1BB as a central co-stimulatory pathway with a strong mechanistic rationale for therapeutic agonism in cancer immunotherapy.

OX40 (CD134)

OX40 is a co-stimulatory receptor of the TNFR superfamily expressed on activated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and Tregs, with its ligand OX40L (CD252) primarily expressed on activated APCs and, under inflammatory conditions, on endothelial and stromal cells [71]. The engagement of OX40 enhances T cell expansion, effector cytokine production, and survival by recruiting TRAF2 and TRAF5, which activate the NF-κB and PI3K–AKT pathways. Stimulation through costimulatory receptors (including OX40) supports metabolic reprogramming that enhances glycolysis and mitochondrial function, helping to sustain longer T cell persistence [74]. OX40 signaling also favors the generation of long-lived memory T cells and can destabilize Tregs by downregulating FoxP3 expression, thus shifting the balance toward effector responses [75]. In addition, agonist anti-OX40 induces robust antitumor activity with expansion of tumor-reactive CD8+ T cells and Treg apoptosis, and, when sequenced appropriately, can synergize with PD-1 blockade [76]. Collectively, these mechanisms establish OX40 as a key regulator of durable T cell immunity and a promising target for agonist-based immunotherapies.

Inducible T cell co-stimulator (ICOS)

ICOS is a co-stimulatory receptor of the CD28 family that is rapidly upregulated following TCR engagement in T cells. Its ligand, ICOSL (B7-H2), is expressed on B cells, macrophages, and DCs [77]. ICOS signaling occurs via a YMFM motif in the cytoplasmic tail, recruiting PI3K and promoting AKT activation, which enhances T cell survival, proliferation, and cytokine production [78]. Functionally, ICOS is indispensable for the differentiation and maintenance of T follicular helper (Tfh) cells, which orchestrate germinal center responses and antibody production [79]. Within the tumor microenvironment, ICOS signaling exerts dual effects, it can augment effector CD4+ and CD8+ T cell function but also sustain ICOS+ Tregs, which reinforce immunosuppression [80]. In murine tumor models, ICOS agonists enhance antitumor immunity by expanding effector T cells and promoting IFN-γ production, whereas the depletion of ICOS+ Tregs further augments therapeutic efficacy [81]. These findings describe ICOS as a context-dependent co-stimulatory pathway, in which the balance between effector activation and Treg expansion is critical for therapeutic success.

Glucocorticoid-induced TNFR-related protein (GITR)

GITR (CD357) is expressed at low levels in resting T cells but is rapidly upregulated upon activation, with constitutive expression in Tregs. Its ligand, GITRL, is expressed on APCs, endothelial cells, and some tumor cells [82]. Engagement of GITR enhances effector T cell proliferation and cytokine production while attenuating the suppressive activity of Tregs [83]. Mechanistically, signaling occurs via TRAF2 and TRAF5, which activate the NF-κB and MAPK pathways to promote survival and effector function [83]. Preclinical studies have demonstrated that GITR agonism can simultaneously expand CD8+ effector T cells and destabilize Tregs, resulting in potent antitumor effects. In murine tumor models, antibody-mediated GITR stimulation reduced intratumoral Treg frequency, increased effector-to-regulatory T cell ratios and synergized with PD-1/PD-L1 blockade to achieve durable tumor regression [84]. These findings demonstrate GITR’s dual action of GITR, strengthening effector responses while weakening immunosuppressive networks, as a compelling rationale for its development as a next-generation co-stimulatory target.

CD40

CD40 is a TNFR family receptor expressed on B cells, DCs, macrophages, and some non-hematopoietic cells, with its ligand CD40L (CD154) predominantly expressed on activated CD4+ T cells [85]. Engagement of CD40 recruits TRAF adaptor proteins, triggering the canonical and non-canonical NF-κB, MAPK, and PI3K signaling cascades [86]. Through these pathways, CD40 activation drives dendritic cell maturation, enhances MHC and co-stimulatory molecule expression, and promotes the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, thereby licensing APCs for effective priming of CD8+ T-cell responses. In macrophages, CD40 stimulation induces tumoricidal activity and amplifies antigen presentation, linking the innate and adaptive immunity. Preclinical models have shown that agonistic CD40 antibodies can convert poorly immunogenic tumors into inflamed tumors, augment T cell infiltration, and synergize with checkpoint blockade to produce durable tumor regression [87]. These features establish CD40 as a central orchestrator of antitumor immunity and a compelling candidate for therapeutic intervention.

Translational and Clinical Progress of Next-Generation Checkpoint Inhibitors

The translation of next-generation checkpoint biology into effective therapies has been marked by important advances and persistent challenges in recent years. Since the approval of anti–CTLA-4 and anti–PD-1/PD-L1 therapies more than a decade ago, the search for additional checkpoints has produced a wave of phase I–III trials testing inhibitory receptors, innate/myeloid checkpoints, and co-stimulatory agonists. As of 2025, the clinical landscape reflects three broad trends: (i) the validated, though incremental, success of LAG-3, (ii) mixed or inconclusive outcomes with targets including TIGIT and TIM-3, (iii) an emerging emphasis on co-stimulatory and innate-immunity pathways (e.g., 4-1BB, OX40, CD40, CD47–SIRPα, and ICOS) designed to reinvigorate effector function and antigen presentation. Table 1 summarizes representative late-phase and emerging clinical trials investigating next-generation checkpoint and co-stimulatory agents. The table integrates objective efficacy metrics with safety outcomes, regulatory status, and critically the key biomarkers explored across studies. This biomarker-anchored view underscores how translational discovery shapes trial design, patient selection, and combination strategies that aim to deliver more durable and mechanistically rational immunotherapy responses.

|

Pathway |

Trial (NCT) & setting |

ORR |

PFS (median /HR) |

OS (median /HR) |

Grade ≥3 TRAEs |

Regulatory Outcome & Take-home |

Key Biomarker Used |

|

TIGIT [89] |

CITYSCAPE (NCT03563716), Phase II, 1L PD-L1+ NSCLC |

31.3% vs 16.2% (p=0.031) |

5.4 vs 3.6 mo; HR 0.57 (95% CI 0.37–0.90; p=0.015) |

Not powered |

Serious TRAEs 21% vs 18%; ↑lipase most frequent (9% vs 3%); 2 treatment-related deaths |

Clear proof-of-concept; supported FDA BTD (2021) |

PD-L1 expression; TIGIT expression |

|

TIGIT / PD-L1 |

SKYSCRAPER-01 (NCT04294810), Phase III, 1L PD-L1-high NSCLC |

45.8% vs 35.1%; DOR 18.0 vs 14.6 mo |

7.0 vs 5.6 mo; HR 0.78; P =.02 (NS vs α<.001) |

23.1 vs 16.9 mo; HR 0.87; P = .22 |

≥G3 AEs: 41.2% vs 33.8%; ≥G3 TRAEs: 19.9% vs 9.5%; immune AEs: 70% vs 50.6%; withdrawals: 16.1% vs 6.5% |

Primary endpoints not met; numerical activity but higher toxicity. |

TIGIT / PD-L1 co-expression; TMB; T-cell activation score |

|

TIGIT |

KEYVIBE-010 (NCT05665595), Phase III, adjuvant high-risk melanoma |

NA (adjuvant) |

Trial stopped early for futility (RFS endpoint not met) |

NA |

Higher immune-mediated discontinuations in combo arm |

Negative trial; futility + safety led to discontinuation. |

TIGIT biomarker details currently unexplored due to early stoppage |

|

LAG-3 [20]. |

RELATIVITY-047 (NCT03470922), Phase II/III, 1L advanced melanoma |

43.1% vs 32.6% |

10.2 vs 4.6 mo; HR 0.78 (95% CI 0.64–0.94) |

Not reached vs 34.1 mo; HR 0.80 (95% CI 0.64–1.01; P=.059) |

≥G3 TRAEs: 21.1% vs 11.1% |

Positive; basis for FDA approval of relatlimab + nivolumab (Opdualag) |

LAG-3 expression; PD-L1 expression |

|

LAG-3 [161]. |

PLATforM (NCT03484923), Phase II platform, PD-1 refractory melanoma |

~10% in LAG525 + spartalizumab arm |

Not reported |

Not reported |

Acceptable safety, no new signals |

Negative; no efficacy signal, arms closed |

LAG-3 expression |

|

TIM-3 |

COSTAR Lung (NCT04655976), Phase II/III, post–PD-1/PD-L1 NSCLC |

NA (trial ongoing) |

Primary endpoint: OS; results pending |

Pending |

Pending |

Ongoing; TIM-3 remains unproven. |

TIM-3 expression; PD-L1 status |

|

4-1BB (CD137) [162] |

Utomilumab monotherapy, Phase I, dose-escalation (NCT01307267); advanced solid tumors incl. MCC |

3.8% overall (CR 1, PR 1); 13.3% in MCC |

1.7 mo (all solid tumors) |

11.2 mo (all solid tumors) |

No DLTs; Grade ≥3 TRAE 1.8% (fatigue); no clinically relevant transaminase elevations |

Favorable safety, modest single-agent activity; supports combination strategies over monotherapy |

Post-dose rise in soluble 4-1BB; peripheral CD4/CD8/NK changes; circulating lymphocyte levels may influence benefit. |

|

OX40 (CD134) [163] |

ICONIC (NCT02315066): ivuxolimab monotherapy, Phase I, dose-escalation; advanced HNSCC, HCC, melanoma, RCC |

5.8% PR (3/52); DCR 56% (single-agent) |

Not consistently reported |

Not reported |

No DLTs; most TRAEs grade ≤2 (fatigue 46%, nausea 29%); one grade 3 GGT increase |

Modest single-agent activity, favorable tolerability; on-target immune activation (full receptor occupancy ≥0.3 mg/kg). Supports combination strategies (e.g., with 4-1BB or anti–PD-1/PD-L1). |

Tumor OX40 expression (on-treatment ↑ correlates with longer TTP); IFN-γ/IL2–STAT5 inflammatory gene-set enrichment in tumor; peripheral CD4/CD8 memory T-cell Ki67 and HLA-DR/CD38; receptor occupancy ≥0.3 mg/kg. |

|

GITR [164] |

NCT02697591 – Phase I/II, dose-escalation/ expansion; advanced or metastatic solid tumors |

2 PR (2%), DCR 36% |

Not reported |

Not reported |

10% grade ≥ 3 TRAEs (mainly fatigue 3%); no MTD reached |

Well tolerated; limited single-agent activity; fatigue most common AE; full receptor occupancy ≥ 5 mg/kg; supports combination development with PD-1/CTLA-4 blockade |

Peripheral Treg depletion (5 mg/kg); ↑ CD8+ Ki67+ T cells; ↑ HLA-DR on CD8 T cells; ↑ CCL17, CD70, CLEC4G plasma proteins; 90% GITR receptor occupancy ≥5 mg/kg |

|

CD47–SIRPα [165] |

NCT03248479, Phase Ib, front-line higher-risk MDS (Magrolimab + Azacitidine) |

ORR 75%, CR 33% (overall); TP53-mutant ORR 69%, CR 45% |

PFS 11.6 mo (95% CI 9.0–14.0) |

OS NR (16.3 mo TP53-mutant) |

Anemia (51.6% all-grade, 47% grade 3); neutropenia (46%); thrombocytopenia (46%); 2.1% 60-day mortality |

Favorable safety with on-target anemia; promising efficacy esp. TP53-mutant; supported Phase III ENHANCE trial (NCT04313881) |

CD47 expression; calreticulin up-regulation; phagocytic index; TP53 mutation status; cytogenetic risk |

|

CD40 (Fc-optimized agonist) [166]

|

ICONIC Trial (NCT02904226) – Phase I/II, advanced solid tumors, monotherapy and combination with nivolumab |

ORR 1.4% (monotherapy); 2.3% (combo) |

Not reported (low durable responses) |

OS benefit restricted to biomarker-positive subset |

Mostly grade 1–2; well-tolerated; no DLTs; transaminase elevation rare |

Well-tolerated but limited activity; responses restricted to patients with emergence of peripheral ICOS-hi CD4 T cells |

ICOS-hi CD4 T cell emergence (pharmacodynamic marker); RNA-based TISvopra predictive biomarker; baseline ICOS/PD-L1 IHC status |

|

PD-1 + VEGFR (Anti-angiogenic IO combination) [167] |

NCT03367741, Phase II, recurrent endometrial cancer (nivolumab ± cabozantinib) |

33% vs 19% (confirmed ORR) |

5.3 vs 3.8 mo; HR 0.65 |

13.6 vs 7.4 mo (HR 0.66) |

Grade ≥3 AEs 67% vs 45%; hypertension and hand–foot syndrome most common |

Combination superior to nivolumab alone; improved PFS and immune activation; supports PD-1 + TKI synergy |

ICOS-L, CD28, CCL23, CSF1, VEGFR2, HO-1; Copy-number high signature; granzyme upregulation |

|

PD-1 (Geptanolimab) [168] |

NCT03502629, Phase II – Relapsed/Refractory Peripheral T cell Lymphoma

|

40.4% (44/109) |

11.4 mo DoR |

12.1 mo median follow-up |

Grade ≥3 TRAEs 16%; immune-related events rare |

Promising activity in PTCL; JAK3 mutations confer resistance via STAT3 pathway; Tofacitinib sensitivity suggested |

PD-L1 expression (≥ 50 % benefit); TMB; JAK3 p.A573V/p.M511I; STAT3 activation status |

|

PD-1 (Immune-sensitive molecular subtypes) [169]

|

PERSEUS1 (NCT03506997) – Phase II single-arm, mCRPC with MMRd or immune-responsive subtypes |

28% (7/25 responders) |

2.8 mo (95 % CI 2.6–5.3) |

16.0 mo (95 % CI 10.0–17.7) |

76 % any TRAEs; 12 % grade 3–4; no deaths |

Pembrolizumab active in MMRd and CDK12-biallelic loss subsets; supports genomic stratification for ICI in mCRPC |

MMRd (IHC MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2); MSI-H; CDK12 biallelic loss; TMB ≥ 11 mut/Mb; CD3+ TIL density; DNA-repair defects (HR/NHEJ) |

|

PD-L1 + VEGFR (Anti-angiogenic Immunotherapy) [170] |

NCT02912572 – Phase II, MMR-proficient recurrent endometrial cancer

|

ORR 25.7 % (95 % CI 12.5–43.3) |

7 mo (95 % CI 3.9–7.5) |

23.8 mo (95 % CI 14.7–NE) |

G3+ AEs: HTN 37 %, ALT/AST ↑ 6 %, 14 % discontinued; no deaths |

Combination met prespecified efficacy; improved tolerability vs pembro/lenva; supports PD-L1/VEGFR synergy in MMRP tumors |

MMR status (IHC MMRP); TP53 mutation (48 % responders); NSMP subtype; FOXP3+/PD-1+ and CD163+ immune cells (mIF) |

|

Abbreviations: AE: Adverse Event; AML: Acute Myeloid Leukemia; BTD: Breakthrough Therapy Designation; CAR T: Chimeric Antigen Receptor T cell; CD40: Cluster of Differentiation 40; CD47: Cluster of Differentiation 47; CR: Complete Response; CTLA-4: Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–Associated Protein 4; DCR: Disease Control Rate; DLBCL: Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma; DLT: Dose-Limiting Toxicity; DOR: Duration of Response; ECOG: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; Fc: Crystallizable Fragment Region; FL: Follicular Lymphoma; G3+: Grade 3 or higher; HCC: Hepatocellular Carcinoma; HNSCC: Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma; HR: Hazard Ratio; HRR: Homologous Recombination Repair; IC50: Half-Maximal Inhibitory Concentration; ICI: Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor; ICOS: Inducible Co-Stimulator; IL: Interleukin; mIF: Multiplex Immunofluorescence; MMRd: Mismatch-Repair-Deficient; MMRp: Mismatch-Repair-Proficient; MTD: Maximum Tolerated Dose; MDS: Myelodysplastic Syndrome; mo: Months; NHL: Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma; NSCLC: Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer; ORR: Objective Response Rate; OS: Overall Survival; PD-1: Programmed Cell Death Protein 1; PD-L1: Programmed Death-Ligand 1; PFS: Progression-Free Survival; PR: Partial Response; PTCL: Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma; R/R: Relapsed/Refractory; RFS: Recurrence-Free Survival; SAE: Serious Adverse Event; SD: Stable Disease; TIL: Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocyte; TISvopra: Transcriptional Immune Signature for Vopratelimab; TKI: Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor; TMB: Tumor Mutational Burden; TRAE: Treatment-Related Adverse Event; VEGFR: Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor; WT: Wild-Type |

|||||||

Adaptive inhibitory checkpoints

LAG-3: The RELATIVITY-047 trial demonstrated that relatlimab combined with nivolumab was superior to nivolumab alone in advanced melanoma, leading to the first approval of a next-generation checkpoint inhibitor in 2022 [20]. This regimen improved progression-free survival with an acceptable safety profile, validating LAG-3 as a therapeutic target after years of preclinical development. Nonetheless, the incremental benefit compared with PD-1 blockade alone has tempered expectations, and ongoing trials in colorectal, hepatocellular, and lung cancers are exploring broader applicability, although clinical signals have so far been modest [88].

TIGIT: Early promise came from the phase II CITYSCAPE trial, in which tiragolumab plus atezolizumab improved responses in PD-L1–positive NSCLC [89]. However, subsequent phase III trials, including SKYSCRAPER-01, failed to meet the primary endpoints. These outcomes underscore the risks of rapidly advancing to late-phase studies without robust biomarker guidance. Current efforts emphasize Fc-engineered and bispecific antibodies (e.g., PD-1 × TIGIT) and the ongoing evaluation of domvanalimab (ARCTIC-3) to refine the therapeutic potential of this pathway [90]. The contrasting outcomes between LAG-3 and TIGIT blockade underscore important mechanistic and translational distinctions. While LAG-3 provides a nonredundant inhibitory signal that complements PD-1 blockade, TIGIT inhibition may depend on Fc-effector engagement and biomarker-guided patient selection to demonstrate efficacy, factors that likely contributed to the negative results of the SKYSCRAPER-01 trial. These developments also illustrate how Fc-engineering directly influences clinical outcomes. Fc-active anti-TIGIT antibodies may deplete TIGIT+ Tregs through ADCC, whereas Fc-silenced formats act primarily as ligand-blocking agents, potentially explaining efficacy differences observed across trials.

TIM-3: Despite a strong biological rationale, TIM-3 inhibitors, such as sabatolimab and cobolimab, have shown limited efficacy as monotherapies [91]. The most notable setback was the discontinuation of the phase III STIMULUS-MDS2 trial in January 2024, after the sabatolimab + azacitidine regimen failed to meet its primary endpoint in higher-risk myelodysplastic syndromes [92]. Current studies are focused on rational combinations of PD-1 inhibitors, chemotherapy, and epigenetic modulators, although enthusiasm has been dampened by the lack of durable single-agent activity [93,94].

VISTA and BTLA: Both targets remain in the early stages of development, with limited clinical data. VISTA inhibitors are undergoing first-in-human testing in solid tumors, whereas BTLA-directed agents are primarily being developed in bispecific antibody formats. Progress in these pathways will likely depend on identifying tumor contexts in which expression is enriched and resistance to PD-1 blockade predominates.

Innate and myeloid checkpoints

CD47–SIRPα: Clinical development of CD47–SIRPα blockade, designed to restore macrophage phagocytosis, has produced mixed results. Early anti-CD47 antibodies generated promising responses in hematologic malignancies but were limited by dose-dependent anemia, a consequence of CD47 expression on red blood cells [95]. To mitigate this on-target toxicity, newer strategies such as selective SIRPα inhibitors and antibodies e.g., magrolimab are under active evaluation [96]. However, multiple phase III trials have been terminated or redesigned, underscoring the translational challenges that continue to confront this pathway [97].

NKG2A: Monalizumab, an anti-NKG2A antibody, has shown encouraging activity in combination with durvalumab in patients with unresectable stage III NSCLC who had not progressed after chemoradiotherapy [98]. These results provide clinical proof-of-concept that innate checkpoint blockade can synergize with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibition, although its efficacy across tumor types remains under investigation.

Siglec-15: As one of the most recently identified checkpoints, Siglec-15 has advanced to early clinical testing with agents such as NC318. Initial findings suggest potential benefit in PD-L1–negative NSCLC, consistent with its largely non-overlapping expression pattern relative to PD-L1. This raises the possibility that Siglec-15 inhibition could serve as a niche strategy for tumors resistant to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade therapy. However, clinical development is still in the early phases, and defining optimal biomarkers for patient selection is essential to realize its therapeutic potential.

Co-stimulatory pathway agonists

4-1BB (CD137): The earliest 4-1BB agonists, such as urelumab, were hampered by dose-limiting hepatotoxicity, whereas utomilumab showed limited clinical activity [99]. To overcome these challenges, second-generation Fc-engineered bispecific antibodies have been designed to restrict signaling to the tumor microenvironment, thereby reducing systemic toxicity. Early trials combining these agents with PD-1 inhibitors have reported manageable safety and preliminary efficacy, suggesting a more viable therapeutic path [100].

OX40: Although OX40 agonists have demonstrated strong preclinical activity, the clinical results have been modest. For example, the OX40 antibody MOXR0916 has shown limited efficacy as a monotherapy [101]. Current developments emphasize bispecific formats (e.g., OX40 × PD-L1) and optimized antibody engineering, which aim to harness the co-stimulatory capacity of this pathway more effectively [102].

ICOS: Agonists targeting ICOS are primarily being tested in bispecific designs, seeking to preferentially expand effector T cells while limiting the activation of ICOS+ regulatory T cells. Although clinical data are still emerging, the selective biology of ICOS has positioned it as a candidate for rational combinatorial strategies rather than standalone therapy.

GITR: Despite compelling preclinical rationale, initial clinical studies of GITR agonists failed to produce durable antitumor responses, leading to the discontinuation of some programs. Ongoing efforts are now focusing on combination regimens and optimized dosing strategies to better leverage the dual activity of enhancing effector T-cell function while reducing Treg suppression.

CD40: Among the co-stimulatory targets, CD40 agonists have shown the greatest translational promise. Agents such as selicrelumab can potently activate dendritic cells, upregulate co-stimulatory molecules, and license CD8+ T-cell priming [103]. However, systemic cytokine release and inflammation remain challenges, and ongoing studies are testing combinations with chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and checkpoint blockade to maximize efficacy while managing the toxicity.

Clinical outcomes of late-phase next-generation checkpoint inhibitor trials

Findings from advanced phase clinical trials revealed varying trajectories among inhibitors targeting TIGIT, LAG-3, and TIM-3. In the Phase II CITYSCAPE trial (NCT03563716), the combination of tiragolumab and atezolizumab in first-line PD-L1+ NSCLC demonstrated an improved ORR (31.3% vs. 16.2%; p=0.031) and PFS (5.4 vs. 3.6 months; HR 0.57; p=0.015) while maintaining an acceptable safety profile, thereby establishing proof of concept [89], the confirmatory Phase III SKYSCRAPER-01 trial (NCT04294810) did not achieve its co-primary endpoints despite numerical gains in ORR and OS and was associated with increased grade ≥3 immune-related toxicities, underscoring the translational limitations of TIGIT in unselected patients. Similarly, the Phase III KEYVIBE-010 trial (NCT05665595) of adjuvant melanoma was terminated early due to futility, further highlighting the inconsistent efficacy of TIGIT blockade.

For LAG-3, the Phase II/III RELATIVITY-047 trial (NCT03470922) validated the relatlimab plus nivolumab regimen in advanced melanoma, demonstrating a higher ORR (43.1% vs. 32.6%), significantly prolonged PFS (10.2 vs. 4.6 months; HR 0.78; P < 0.01), and a favorable safety profile, forming the basis for the first regulatory approval of a LAG-3 inhibitor [20]. In contrast, the PLATforM trial (NCT03484923), which combined spartalizumab with LAG525 in PD-1 refractory melanoma, failed to meet the prespecified efficacy thresholds (ORR ~10%), indicating that not all LAG-3 approaches replicate the relatlimab signal.

In comparison, the role of TIM-3 remains to be elucidated. The COSTAR Lung trial (NCT04655976), which evaluated cobolimab plus dostarlimab and docetaxel in advanced NSCLC post-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy, has progressed to Phase III expansion but lacks mature OS data. To date, TIM-3 has not demonstrated the reproducible clinical benefits of LAG-3.

These outcomes collectively underscore the validated yet incremental progress of LAG-3, the uncertain trajectory of TIGIT, and the unproven role of TIM-3. A comparative overview of the efficacy and safety results from these trials is provided in Table 1, which highlights the translational significance and regulatory outcomes of each program.

Integration of co-stimulatory pathway agonists with emerging immunotherapies

Recent evidence indicates that integrating co-stimulatory agonists into cellular and vaccine-based immunotherapies may redefine the cancer therapeutic landscape. By activating multiple immune pathways, these agents can amplify antitumor immunity and substantially improve clinical outcomes. Key receptors such as 4-1BB (CD137), OX40 (CD134), and CD40 are pivotal in enhancing T cell persistence, cytotoxicity, and memory formation featuring that are particularly valuable in optimizing the efficacy of CAR T cell therapy. Activation of these pathways mitigates T cell exhaustion and improves response persistence in solid tumors [104,105]. Co-stimulatory signaling through 4-1BB and OX40 has been shown to synergistically strengthen effector and memory T cell functions following activation [105,106]. Moreover, these co-stimulatory mechanisms significantly enhance the potency of therapeutic cancer vaccines by promoting dendritic cell priming and robust T cell expansion, thereby improving the immunogenicity of neoantigen and mRNA-based vaccine platforms. Preclinical data demonstrate that combining OX40 or CD40 agonists with neoantigen vaccines markedly augments antigen-specific immunity [107,108], reinforcing the concept that multimodal co-stimulation can overcome tumor-induced immune suppression [109,110]. Engagement of these co-stimulatory axes also complements checkpoint blockade, providing a rationale for precision combination strategies that unite MyD88 and CD40 co-stimulation to enhance CAR T cell expansion, function, and antitumor efficacy in solid malignancies [111–113]. These findings emphasize the potential of integrating co-stimulatory agonists across various immunotherapeutic platforms to synergistically harness both adaptive and innate immunity, thereby achieving durable and long-term tumor control [110].

Toxicities and safety challenges associated with next-generation checkpoint modulation

The therapeutic translation of next-generation checkpoint modulators has been strongly shaped by their safety profiles, which differ between inhibitory and co-stimulatory mechanisms. Inhibitory checkpoint blockade generally produces irAEs like PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors, whereas co-stimulatory receptor agonists can induce cytokine-driven toxicities that limit their dosing range. Among inhibitory pathways, LAG-3 blockade (relatlimab + nivolumab, RELATIVITY-047) showed toxicity patterns overlapping with PD-1 blockade, primarily fatigue, rash, and pruritus, with grade ≥3 irAEs in about 19% of patients [20,88]. TIGIT inhibitors, such as tiragolumab and vibostolimab, when combined with PD-1/PD-L1 blockade, show a toxicity profile overlapping that of PD-1/PD-L1 monotherapy (rash, diarrhea, thyroid dysfunction). In the phase II CITYSCAPE trial, tiragolumab plus atezolizumab was associated with a slightly higher rate of grade ≥3 treatment-related adverse events compared with atezolizumab alone (e.g. lipase elevation: 9% vs 3%) [89]. Early-stage TIM-3 blockade trials have demonstrated generally tolerable safety profiles; however, combination regimens appear to carry a higher risk of immune-related adverse events such as transaminitis and colitis, though clinical evidence remains limited and continues to evolve [114]. Additionally, clinical trials investigating VISTA and BTLA inhibitors have reported a range of immune-related adverse events, including infusion reactions, fatigue, and cytopenias, with more significant Grade 3 or higher toxicities like hepatitis and pneumonitis noted particularly in combination regimens [115].

Among innate checkpoint targets, blockade of the CD47–SIRPα axis is notable for producing predictable hematologic toxicities, including anemia and thrombocytopenia, caused by on-target red cell clearance [116]. Therapies targeting NKG2A (monalizumab) have shown a generally manageable safety profile in early trials, but serious treatment-related adverse events (Grade 3/4) have been reported (e.g., anemia, hydronephrosis, elevated creatinine) in combination settings [117]. In contrast, clinical experience with Siglec-15 blockade (NC318) is still nascent, available data suggest acceptable tolerability, but there is insufficient evidence at present to confirm specific high-grade immune toxicities like colitis or pneumonitis [118].

Within the co-stimulatory class, early clinical development of first-generation 4-1BB (CD137) agonists was hampered by dose-dependent hepatotoxicity, as the prototype antibody urelumab induced severe liver inflammation through Fcγ-receptor-mediated activation of hepatic macrophages [119]. These safety challenges led to the development of second-generation 4-1BB agonists, including bispecific and Fc-attenuated antibodies, designed to confine receptor activation to the tumor microenvironment and thereby improve tolerability while preserving antitumor efficacy. Early clinical studies of OX40 agonists (such as ivuxolimab and MOXR0916) demonstrated manageable safety profiles characterized primarily by grade 1–2 fatigue, rash, nausea, and diarrhea. Nevertheless, clinical progress was constrained by modest efficacy and, in some cases, cytokine release syndrome, which limited further dose escalation [120]. Similarly, the ICOS agonist vopratelimab showed good tolerability in the ICONIC trial, with common events including infusion reactions and mild gastrointestinal symptoms [44]. In comparison, GITR agonists (TRX518, MEDI1873) have shown pruritus, rash, and transient cytokine-related fever but no severe or dose-limiting toxicities [121]. Among co-stimulatory targets, CD40 agonists remain notable for cytokine-release syndrome and systemic inflammation driven by monocyte and macrophage activation and surges of TNFα and IL-6 [122].

Resistance Mechanisms and Therapeutic Combinations

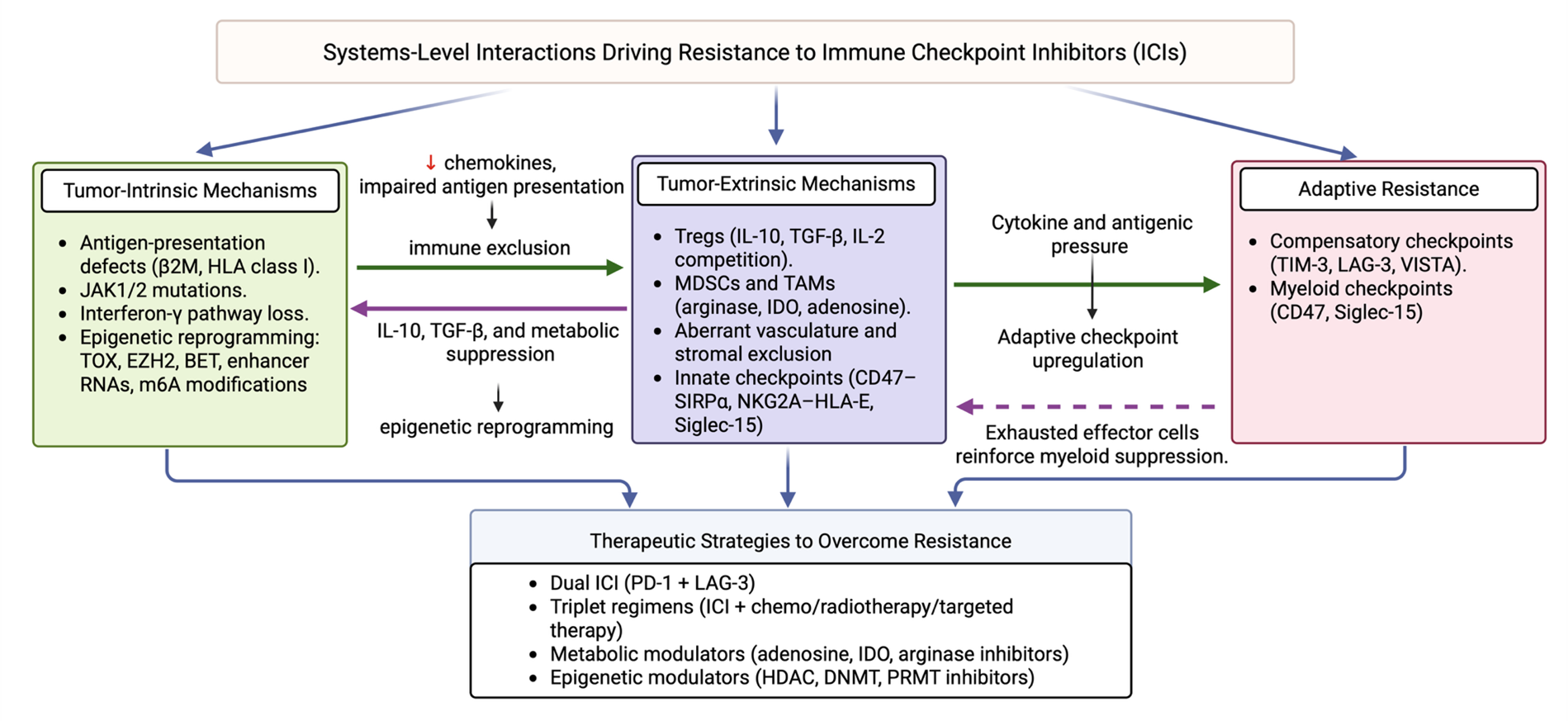

Although ICIs have transformed cancer therapy, durable responses remain restricted to a minority of patients with cancer. Resistance arises through a complex interplay of tumor-intrinsic, tumor-extrinsic, and adaptive compensatory mechanisms that converge to limit antitumor immunity [123]. Understanding these resistance pathways provides a foundation for rational combinatorial strategies aimed at broadening the efficacy of next-generation checkpoint inhibitors. These mechanisms can be broadly categorized into tumor-intrinsic, tumor-extrinsic, and adaptive resistance pathways (Figure 1). These resistance mechanisms do not operate in isolation but rather function as an interconnected, self-reinforcing network. Tumor-intrinsic defects such as JAK/STAT mutations, β2-microglobulin loss, or epigenetic remodeling reduce interferon-γ responsiveness and chemokine production, resulting in diminished immune infiltration and establishment of a suppressive microenvironment. This evolving tumor microenvironment, enriched with suppressive cytokines such as IL-10 and TGF-β and metabolic by-products from myeloid cells, in turn feeds back to strengthen intrinsic immune escape through sustained epigenetic reprogramming and checkpoint upregulation. The therapeutic efforts targeting this axis include EZH2 inhibitors (e.g., tazemetostat) and BET inhibitors (e.g., birabresib, molibresib), which are being explored to reverse immune exhaustion-associated chromatin states and restore T cell functionality [124–128]. Over time, persistent cytokine signaling and antigenic pressure drive the adaptive induction of compensatory checkpoints, including PD-1, LAG-3, and TIM-3, establishing a chronic equilibrium between immune activation and suppression. Together, these multilayered interactions form a dynamic ecosystem that perpetuates resistance to immune checkpoint blockade.

Figure 1. Interconnected mechanisms of resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs). The schematic illustrates the bidirectional interplay between tumor-intrinsic, tumor-extrinsic, and adaptive resistance mechanisms.

Tumor-intrinsic mechanisms

Defects in antigen presentation are frequent causes of primary resistance. Loss-of-function alterations in β2-microglobulin or HLA class I molecules impair peptide loading and presentation to cytotoxic T lymphocytes, effectively rendering tumor cells invisible to immune surveillance [129]. Similarly, mutations in interferon-γ signaling components, such as JAK1 and JAK2, prevent the transcriptional upregulation of antigen-processing machinery and effector chemokines, undermining the cytolytic T cell response [10]. In addition to genetic lesions, epigenetic reprogramming contributes to resistance by enforcing stable T cell exhaustion states. Chromatin remodeling at exhaustion-specific enhancers, coupled with dysregulation of transcription factors such as TOX, creates a fixed dysfunctional state refractory to PD-1 or CTLA-4 blockade [130]. Emerging evidence suggests that enhancer RNAs (eRNAs) and epitranscriptomic regulators, including m6A modifications, further shape checkpoint resistance, and providing new mechanistic links between chromatin dynamics and immunotherapy outcomes.

Tumor-extrinsic mechanisms

The immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME) remains a dominant barrier to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Tregs attenuate effector responses through IL-10, TGF-β, and metabolic competition for IL-2, whereas myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) produce arginase, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), and adenosine, depleting nutrients and enforcing suppression [131]. In parallel, aberrant vasculature and stromal remodeling restrict lymphocyte infiltration, maintaining “immune-excluded” or “cold” tumor phenotypes that resist checkpoint blockade.

Adaptive resistance

Even in tumors that initially respond, the adaptive upregulation of compensatory checkpoints can mediate relapse. TIM-3, LAG-3, and VISTA are frequently induced in T cells following PD-1 blockade, reinforcing exhaustion and sustaining immune escape [132]. Similarly, myeloid checkpoints such as CD47 and Siglec-15 may be upregulated in PD-L1–negative tumors, offering alternative escape routes. This dynamic rewiring underscores the need for multipronged therapeutic strategies.

Combination therapy has emerged as a central paradigm for overcoming these diverse resistance mechanisms. Dual checkpoint blockade has already demonstrated proof-of-concept, with LAG-3 plus PD-1 inhibition extending benefits in melanoma [88]. Rational triplets that integrate ICIs with targeted therapies, chemotherapy, or radiotherapy aim to exploit tumor vulnerabilities and enhance immunogenic cell death [133]. Novel strategies targeting the metabolic dimension of the TME include adenosine receptor antagonists, arginase inhibitors, and IDO2 blockade. Epigenetic modulators such as HDAC, DNMT, and PRMT inhibitors are being tested to reverse exhaustion-associated chromatin states and restore T cell functionality. Finally, engineered cytokines (IL-2 and IL-15 variants) and costimulatory agonists (4-1BB, OX40, and CD40) are being integrated with ICIs to simultaneously release inhibitory brakes and strengthen activation signals.

Taken together, these approaches illustrate that resistance is not defined by a single barrier, but by an interconnected network of tumor-intrinsic, extrinsic, and adaptive factors. Effective next-generation therapies will require precision combinations that are tailored to the specific resistance landscape of each tumor, guided by biomarkers that identify the dominant escape pathways in individual patients.

Integrative Biomarker Strategies for Next-Generation Checkpoint Blockade

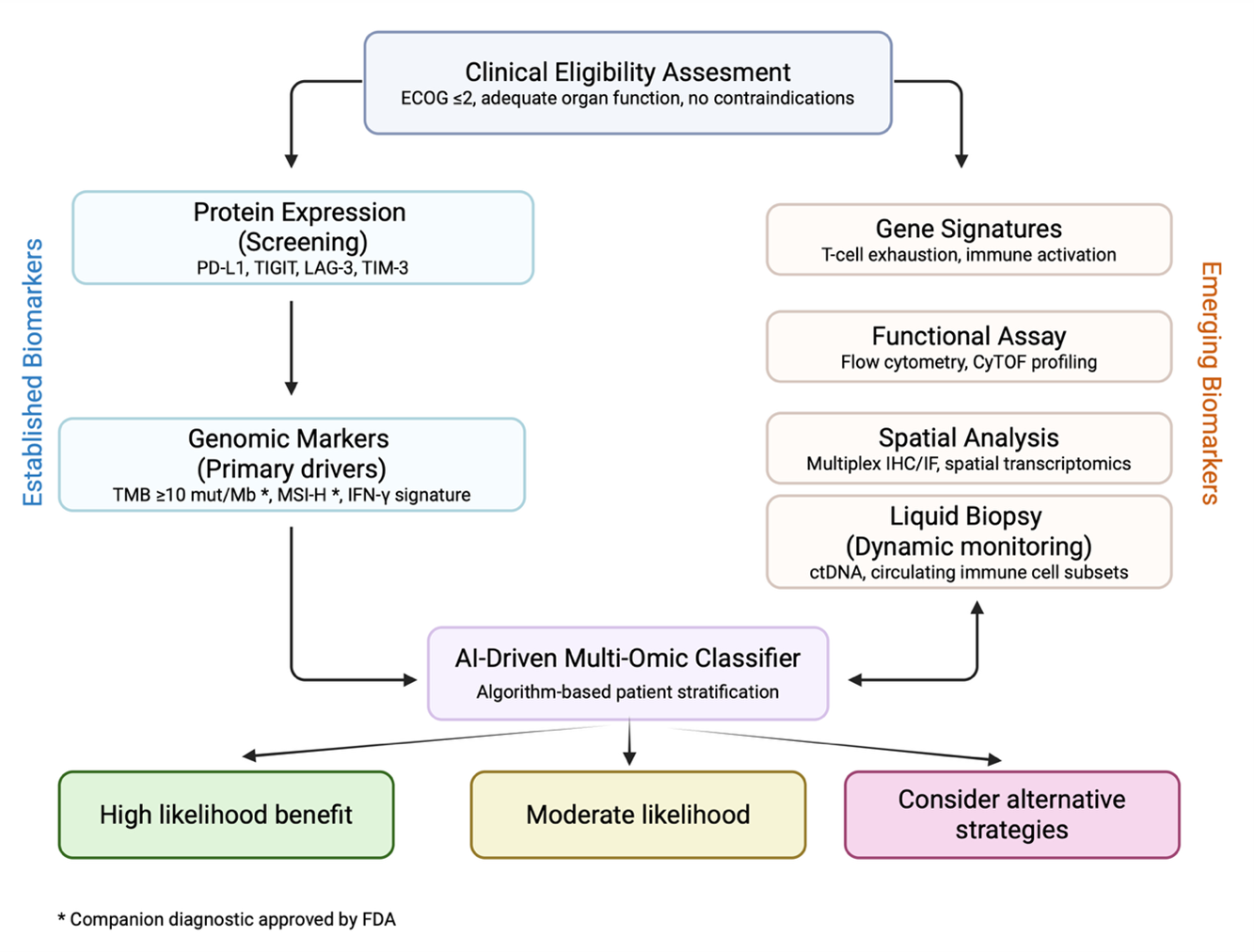

The heterogeneous responses to immune checkpoint inhibitors highlight the need for clinically actionable biomarkers to guide patient selection. While PD-L1 expression and tumor mutational burden (TMB) have been widely adopted in clinical practice, their predictive value is limited. PD-L1 immunohistochemistry suffers from assay and tumor-type variability, and TMB lacks sensitivity in cancers with immunologically “cold” microenvironments [134,135]. As the field transitions to next-generation checkpoint inhibitors, more integrative biomarker strategies are emerging. Figure 2 illustrates a conceptual framework for biomarker-driven patient stratification, integrating established and emerging modalities into a structured decision-making algorithm for next-generation checkpoint blockade. Artificial intelligence applied to multi-omic datasets integrates receptor expression, ligand context, immune architecture, and ctDNA dynamics to generate adaptive predictive signatures that inform ongoing trial designs [136].

Figure 2. AI-driven multi-omic framework for adaptive biomarker-guided immunotherapy. Established biomarkers (protein expression, genomic drivers) with emerging biomarkers (gene signatures, functional assays, spatial analysis, and liquid biopsy) to inform patient stratification for next-generation immune checkpoint inhibitors. An AI-driven multi-omic classifier synthesizes receptor expression, ligand context, immune architecture, and ctDNA dynamics to generate predictive signatures for checkpoint response.

Functional relevance of checkpoint expression

Direct measurement of target expression provides an intuitive biomarker, yet its predictive capacity remains inconsistent. For example, LAG-3 expression correlates with exhausted T cell phenotypes in melanoma and gastric cancer [137], but baseline expression failed to predict benefit from relatlimab plus nivolumab in RELATIVITY-047 [88]. Similarly, TIGIT expression often coincides with PD-1 on CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, yet in CITYSCAPE, responses were enriched primarily in patients with PD-L1–high tumors (≥50%), underscoring the importance of ligand context [89]. In myelodysplastic syndromes, TIM-3 expression on leukemic stem cells provided the rationale for sabatolimab development, but the failure of STIMULUS-MDS1 illustrates the limitations of relying on expression alone [138]. Collectively, these findings emphasize that receptor expression must be interpreted alongside transcriptional, metabolic, and epigenetic state profiling, rather than as an isolated biomarker.

Tumor microenvironment profiling

Advances in multiplex immunohistochemistry, spatial transcriptomics, and imaging mass cytometry now permit high-resolution mapping of immune cell density, distribution, and interactions. For innate checkpoints, biomarker discovery must extend beyond T cells: CD47-SIRPα blockade shows greatest promise in myeloid-rich tumors, yet toxicity arises from ubiquitous CD47 expression on erythrocytes, driving interest in myeloid gene signatures and tumor-to-normal CD47 ratios as predictive tools [139]. NKG2A expression on NK cells and CD8+ T cells correlates with tumor HLA-E upregulation, positioning it as a functional biomarker for monalizumab based strategies [67]. Siglec-15, frequently expressed in PD-L1–negative NSCLC, exhibits largely mutually exclusive expression with PD-L1, marking it as a niche biomarker for PD-1/PD-L1–resistant tumors [68]. These examples highlight how spatially resolved datasets and ligand–receptor context can stratify patients more effectively than expression alone.

Circulating signatures of checkpoint response

Liquid biopsy strategies are increasingly adopted in immunotherapy trials, providing minimally invasive insights into treatment response and resistance dynamics. Recent studies show that ctDNA clearance after one cycle of ICI therapy correlates with significantly improved progression-free survival and overall survival in patients with unresectable stage III NSCLC. Conversely, patients with persistent or rising ctDNA exhibit poor outcomes [140]. Additionally, ctDNA patterns fall into three response categories, complete clearance (molecular responders), initial decline with rebound (acquired resistance), and continuous rise (nonresponders), highlighting its potential for early therapeutic monitoring [141]. While earlier work focused on LAG-3 and TIM-3 blockade, newer methods in TCR-seq, especially single-cell platforms, enabling more sensitive tracking of expansion of tumor-reactive clonotypes in response to ICIs [142]. Emerging data on circulating soluble LAG-3 (sLAG-3) suggest it may signal poor prognosis in NSCLC and other cancers; higher pre-treatment sLAG-3 correlates with reduced PFS and OS, and combining sLAG-3 levels with CD4/CD8 ratios improves prognostic precision [143]. Complementary studies continues to explore panels of soluble cytokines and checkpoint receptors as minimally invasive immune activation markers [144].

Composite and integrated predictive signatures

Integrated immune signatures are emerging as powerful and clinically relevant predictors of response to next-generation checkpoint blockade therapies. The recently developed Immune Profile Score (IPS) exemplifies a multi-omic biomarker designed for broad clinical applicability, demonstrating generalizability across diverse cancer types and immunotherapy contexts [145]. Similarly, recent reviews emphasize that integrating transcriptomic, genomic, and epigenomic layers into multi-omic predictive models substantially improves the accuracy of ICI response predictions compared to single-modality approaches [146]. In addition to multi-omic strategies, advances in artificial intelligence are also accelerating biomarker development: the SCORPIO model, trained on routine clinical variables such as complete blood counts and metabolic markers, was validated in nearly 10,000 patients across 21 tumor types and outperformed established biomarkers like PD-L1 and TMB [147]. These developments complement earlier studies showing that interferon-γ–related gene expression, exhaustion-associated transcriptional programs, and macrophage activation signatures correlate with responsiveness to checkpoint combinations and innate checkpoint blockade [17,148,149]. Nevertheless, the clinical implementation of such multi-omic and spatially resolved assays remains challenging due to assay complexity, cost, and the need for harmonized analytical standards across clinical settings. Moreover, emerging work suggests that functional biomarkers reflecting the metabolic or epigenetic fitness of tumor-infiltrating T cells, rather than their density alone, may provide superior predictive insight for patient stratification [150].

Biomarkers of toxicity and immune-related adverse events

Biomarkers are equally needed to anticipate irAEs, which frequently limit the clinical implementation of checkpoint blockade therapy. For co-stimulatory agonists, hepatotoxicity from systemic 4-1BB activation has been mechanistically linked to Fcγ receptor crosslinking in hepatic macrophages, suggesting that baseline myeloid activity could serve as a predictive biomarker of toxicity [151]. Likewise, host-intrinsic factors such as germline polymorphisms in immune-regulatory genes and extrinsic factors such as gut microbiome composition have been associated with irAE susceptibility across multiple ICI regimens [152]. Incorporating these risk stratifiers into early-phase trials of next-generation agents will be essential to balance efficacy with safety.

Overall, the evidence points to a future in which next-generation checkpoint therapy must be applied selectively rather than universally. Precision immunotherapy, anchored in checkpoint-specific biomarkers that integrate receptor expression, ligand context, TME composition, and dynamic immune monitoring, will be required to identify which patients are most likely to benefit from a given pathway. Embedding biomarker discovery prospectively into trial design, rather than limiting it to retrospective analysis, will be critical to realizing the full potential of next-generation checkpoint blockade.

Future Directions and Clinical Implementation

The future of immune checkpoint therapy will depend on both scientific innovation and the pragmatic policies needed to ensure that these therapies reach patients who are most likely to benefit from them. Lessons from the past decade, marked by incremental gains with LAG-3, setbacks with TIGIT and TIM-3, and toxicities with CD47 and 4-1BB agonists, highlight both the potential and the limitations of this approach. Next-generation strategies increasingly focus on multi-specific antibodies and fusion constructs, such as PD-1 × LAG-3 [153] or PD-1 × TIGIT [154,155] bi-specifics designed to overcome redundant inhibitory pathways, PD-L1 × 4-1BB constructs that confine co-stimulation to the tumor microenvironment [44], and fusion proteins coupling checkpoint blockade with cytokine payloads like IL-2 for targeted immune amplification [156,157]. Mechanistic bispecifics, such as PD-1 × TIGIT or LAG-3 × PD-L1, primarily co-block redundant inhibitory signals, whereas conditional bispecifics like PD-L1 × 4-1BB restrict activation to the tumor microenvironment, thereby enhancing efficacy while minimizing systemic toxicity. In parallel, advances in synthetic biology are enabling engineered T- and NK-cell therapies with intrinsic resistance to exhaustion, whether through checkpoint knockouts (PD-1, LAG-3), dominant-negative receptors, or armored platforms engineered to secrete cytokines (IL-15, IL-12) and express co-stimulatory ligands (OX40L, 4-1BBL) [158]. However, T cell exhaustion within the engineered product remains a key limitation, which armored CAR-T and TCR-T constructs aim to overcome through intrinsic cytokine signaling and metabolic reinforcement. Combinatorial approaches with epigenetic and metabolic modulators also hold promise, as inhibitors of PRMTs, HDACs, and DNMTs can reprogram exhaustion-associated states [159], while adenosine receptor antagonists, arginase inhibitors, and IDO2 blockade may synergize with myeloid-targeting checkpoints like CD47–SIRPα and Siglec-15 [160]. Implementing these therapies in the clinic will require precise patient selection. Artificial intelligence applied to multi-omic datasets is already generating predictive signatures for checkpoint response by integrating receptor expression, ligand context, immune architecture, and ctDNA dynamics, thereby guiding adaptive trial designs. Simultaneously, clinical translation must confront challenges of toxicity, cost, and equity. Hepatotoxicity associated with systemic 4-1BB agonists underscores the importance of localized or conditional activation strategies. Similarly, anemia with CD47 blockade highlights the need for bispecifics that spare hematopoiesis, while the high cost of multispecific antibodies and engineered cytokines will require health-economic modeling and equitable deployment strategies. Taken together, these developments signal the evolution of checkpoint inhibition into precision-engineered modulation, where rational design, biomarker integration, and adaptive implementation will shape the future of immunotherapy.

Conclusions

Immune checkpoint inhibition has transformed the standard of cancer care in oncology, however, the plateau in durable benefit from CTLA-4 and PD-1/PD-L1 blockade indicates that the next stage will demand new strategies. The first wave of next-generation checkpoints has yielded both advances and setbacks; LAG-3 has emerged as a validated addition, whereas TIGIT, TIM-3, and CD47 illustrate the pitfalls of overreliance on expression alone and the need for biomarker-guided precision.

Looking ahead, progress will depend less on individual targets than on how they are combined, engineered, and clinically implemented. Multi-specific antibodies, synthetic biology enabled cellular therapies, and integration with epigenetic or metabolic interventions are already beginning to reshape the field of immunotherapy. At the same time, AI-driven biomarker platforms offer a path toward real-time patient stratification and adaptive trial design. Achieving durable success will require coupling these innovations with strategies that manage toxicity, ensure scalability, and expand equitable access. If realized, checkpoint modulation has the potential to move from incremental gains to truly transformative impact across cancer care. Taken together, these advances signify a transition beyond the era of monotherapy checkpoint blockade toward rational, biomarker-guided combinations that engage multiple layers of the cancer–immune interface.

References

2. Garon EB, Rizvi NA, Hui R, Leighl N, Balmanoukian AS, Eder JP, et al. Pembrolizumab for the treatment of non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015 May 21;372(21):2018–28.

3. Ansell SM, Lesokhin AM, Borrello I, Halwani A, Scott EC, Gutierrez M, et al. PD-1 blockade with nivolumab in relapsed or refractory Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2015 Jan 22;372(4):311–9.

4. Ferris RL, Blumenschein Jr G, Fayette J, Guigay J, Colevas AD, Licitra L, et al. Nivolumab for recurrent squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 2016 Nov 10;375(19):1856–67.

5. Choueiri TK, Tomczak P, Park SH, Venugopal B, Ferguson T, Symeonides SN, et al. Overall Survival with Adjuvant Pembrolizumab in Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2024 Apr 18;390(15):1359–71.

6. Sharma P, Hu-Lieskovan S, Wargo JA, Ribas A. Primary, Adaptive, and Acquired Resistance to Cancer Immunotherapy. Cell. 2017 Feb 9;168(4):707–23.

7. Darvin P, Toor SM, Sasidharan Nair V, Elkord E. Immune checkpoint inhibitors: recent progress and potential biomarkers. Exp Mol Med. 2018 Dec 13;50(12):1–11.

8. Hong MMY, Maleki Vareki S. Addressing the Elephant in the Immunotherapy Room: Effector T-Cell Priming versus Depletion of Regulatory T-Cells by Anti-CTLA-4 Therapy. Cancers (Basel). 2022 Mar 20;14(6):1580.

9. Galon J, Bruni D. Approaches to treat immune hot, altered and cold tumours with combination immunotherapies. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2019 Mar;18(3):197–218.

10. Zaretsky JM, Garcia-Diaz A, Shin DS, Escuin-Ordinas H, Hugo W, Hu-Lieskovan S, et al. Mutations Associated with Acquired Resistance to PD-1 Blockade in Melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2016 Sep 1;375(9):819–29.

11. Berland L, Gabr Z, Chang M, Ilié M, Hofman V, Rignol G, et al. Further knowledge and developments in resistance mechanisms to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Front Immunol. 2024 Jun 5;15:1384121.

12. Vijayan D, Young A, Teng MWL, Smyth MJ. Targeting immunosuppressive adenosine in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017 Dec;17(12):709–24.

13. Labani-Motlagh A, Ashja-Mahdavi M, Loskog A. The Tumor Microenvironment: A Milieu Hindering and Obstructing Antitumor Immune Responses. Front Immunol. 2020 May 15;11:940.

14. Dougan M. Checkpoint Blockade Toxicity and Immune Homeostasis in the Gastrointestinal Tract. Front Immunol. 2017 Nov 15;8:1547.

15. de Filette J, Andreescu CE, Cools F, Bravenboer B, Velkeniers B. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Endocrine-Related Adverse Events Associated with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Horm Metab Res. 2019 Mar;51(3):145–56.

16. Dougan M, Luoma AM, Dougan SK, Wucherpfennig KW. Understanding and treating the inflammatory adverse events of cancer immunotherapy. Cell. 2021 Mar 18;184(6):1575–88.

17. Zhang B, Wu Q, Zhou YL, Guo X, Ge J, Fu J. Immune-related adverse events from combination immunotherapy in cancer patients: A comprehensive meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int Immunopharmacol. 2018 Oct;63:292–98.

18. Da L, Teng Y, Wang N, Zaguirre K, Liu Y, Qi Y, et al. Organ-Specific Immune-Related Adverse Events Associated With Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Monotherapy Versus Combination Therapy in Cancer: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Front Pharmacol. 2020 Jan 30;10:1671.

19. Paik J. Nivolumab Plus Relatlimab: First Approval. Drugs. 2022 Jun;82(8):925–31.

20. Long GV, Stephen Hodi F, Lipson EJ, Schadendorf D, Ascierto PA, Matamala L, et al. Overall Survival and Response with Nivolumab and Relatlimab in Advanced Melanoma. NEJM Evid. 2023 Apr;2(4):EVIDoa2200239.

21. Marin-Acevedo JA, Dholaria B, Soyano AE, Knutson KL, Chumsri S, Lou Y. Next generation of immune checkpoint therapy in cancer: new developments and challenges. J Hematol Oncol. 2018 Mar 15;11(1):39.

22. Marin-Acevedo JA, Kimbrough EO, Lou Y. Next generation of immune checkpoint inhibitors and beyond. J Hematol Oncol. 2021 Mar 19;14(1):45.

23. Aggarwal V, Workman CJ, Vignali DAA. LAG-3 as the third checkpoint inhibitor. Nat Immunol. 2023 Sep;24(9):1415–22.

24. Demeure CE, Wolfers J, Martin-Garcia N, Gaulard P, Triebel F. T Lymphocytes infiltrating various tumour types express the MHC class II ligand lymphocyte activation gene-3 (LAG-3): role of LAG-3/MHC class II interactions in cell-cell contacts. Eur J Cancer. 2001 Sep;37(13):1709–18.

25. Wang J, Sanmamed MF, Datar I, Su TT, Ji L, Sun J, et al. Fibrinogen-like Protein 1 Is a Major Immune Inhibitory Ligand of LAG-3. Cell. 2019 Jan 10;176(1-2):334-347.e12.

26. Kouo T, Huang L, Pucsek AB, Cao M, Solt S, Armstrong T, et al. Galectin-3 Shapes Antitumor Immune Responses by Suppressing CD8+ T Cells via LAG-3 and Inhibiting Expansion of Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells. Cancer Immunol Res. 2015 Apr;3(4):412–23.

27. Huang RY, Eppolito C, Lele S, Shrikant P, Matsuzaki J, Odunsi K. LAG3 and PD1 co-inhibitory molecules collaborate to limit CD8+ T cell signaling and dampen antitumor immunity in a murine ovarian cancer model. Oncotarget. 2015 Sep 29;6(29):27359-77.

28. Andrews LP, Butler SC, Cui J, Cillo AR, Cardello C, Liu C, et al. LAG-3 and PD-1 synergize on CD8+ T cells to drive T cell exhaustion and hinder autocrine IFN-γ-dependent anti-tumor immunity. Cell. 2024 Aug 8;187(16):4355-4372.e22.

29. Yu X, Harden K, Gonzalez LC, Francesco M, Chiang E, Irving B, et al. The surface protein TIGIT suppresses T cell activation by promoting the generation of mature immunoregulatory dendritic cells. Nat Immunol. 2009 Jan;10(1):48–57.

30. Stanietsky N, Simic H, Arapovic J, Toporik A, Levy O, Novik A, et al. The interaction of TIGIT with PVR and PVRL2 inhibits human NK cell cytotoxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009 Oct 20;106(42):17858–63.

31. Chauvin JM, Pagliano O, Fourcade J, Sun Z, Wang H, Sander C, et al. TIGIT and PD-1 impair tumor antigen-specific CD8⁺ T cells in melanoma patients. J Clin Invest. 2015 May;125(5):2046–58.

32. Johnston RJ, Comps-Agrar L, Hackney J, Yu X, Huseni M, Yang Y, et al. The immunoreceptor TIGIT regulates antitumor and antiviral CD8(+) T cell effector function. Cancer Cell. 2014 Dec 8;26(6):923–37.

33. Liu S, Zhang H, Li M, Hu D, Li C, Ge B, et al. Recruitment of Grb2 and SHIP1 by the ITT-like motif of TIGIT suppresses granule polarization and cytotoxicity of NK cells. Cell Death Differ. 2013 Mar;20(3):456–64.

34. He W, Zhang H, Han F, Chen X, Lin R, Wang W, et al. CD155T/TIGIT Signaling Regulates CD8+ T-cell Metabolism and Promotes Tumor Progression in Human Gastric Cancer. Cancer Res. 2017 Nov 15;77(22):6375–88.

35. Shao Q, Wang L, Yuan M, Jin X, Chen Z, Wu C. TIGIT Induces (CD3+) T Cell Dysfunction in Colorectal Cancer by Inhibiting Glucose Metabolism. Front Immunol. 2021 Sep 29;12:688961.

36. Sipol A, Hameister E, Xue B, Hofstetter J, Barenboim M, Öllinger R, et al. MondoA drives malignancy in B-ALL through enhanced adaptation to metabolic stress. Blood. 2022 Feb 24;139(8):1184–97.

37. Du W, Yang M, Turner A, Xu C, Ferris RL, Huang J, et al. TIM-3 as a Target for Cancer Immunotherapy and Mechanisms of Action. Int J Mol Sci. 2017 Mar 16;18(3):645.

38. Tang R, Rangachari M, Kuchroo VK. Tim-3: A co-receptor with diverse roles in T cell exhaustion and tolerance. Semin Immunol. 2019 Apr;42:101302.