Abstract

Background: Mycosis fungoides (MF) is the most common cutaneous T cell lymphoma (CTCL). Tumor-derived exosomes are endosome-derived extra-cellular-vesicles secreted by cancer cells to create tumor favorable niche. We previously demonstrated that MF-exosomes deliver a significant load of miR-155 and miR-1246 into recipient cells and increase their motility. Literature MF-derived exosomes is strikingly lacking.

Objective: We aim to characterize the protein profile of MF-derived exosomes and to explore the effect of MF-exosomes on immune cells and tumor heterogeneity.

Material and methods: MF-exosomes were isolated from CTCL cell lines and plasma samples from patients with early-MF and healthy controls, using ultracentrifugation. Exosome proteomic content was analyzed via mass spectrometry, verified by FACS-beads, and exosome-protein delivery by immunostaining of target cells. Survival by MTT viability assay. Apoptosis via FACS of annexin-V+PI staining. Treg cells were identified through FACS and FOXP3 expression by qRT-PCR. Immune cell characterization and expression of immune regulators were assessed using mass flow cytometry by time of flight (CyTOF).

Results: OX40, GITR, CXCR4, CD44, and CD30 were identified in MF exosomes. MJ-Exosomes (advanced-MF) desensitized MyLa-cells (localized-MF) to doxorubicin in dependency on CXCR4 receptor. MF-exosomes facilitated apoptosis of T-cells and Treg expansion. CyTOF of PBMCs from healthy donors showed that MF-exosomes decrease the frequency of Th1, TEM/CD4+, Th17, Teffectory/CD8+, M1, and DC, whereas the frequency of M2 increased the expression of PD-L1and CTLA-4.

Conclusions: Our study characterized the protein cargo of MF-exosomes and offers a novel exosome-mediated mechanism underlying immune evasion and chemoresistance in MF.

Keywords

Exosomes, Mycosis fungoides (MF), Cutaneous T cell lymphoma (CTCL), PD-L1, Immune evasion

Introduction

Cutaneous T cells lymphoma (CTCL) is a heterogeneous group of T-cell lymphoma [1] characterized by infiltration of malignant monoclonal T lymphocytes in the skin [1]. Mycosis fungoides (MF), the most common type of CTCL, initially presents as an early-stage of the disease, characterized by persistent, progressive erythematous patches or thin plaques of variable size and shape, which can progress to advanced stage of the disease. Sèzary Syndrome (SS) is the aggressive and leukemic CTCL variant characterized by circulating atypical T-cells, considered as the leukemic phase of MF [2].

Exosomes are small EVs (30-150 nm) of endocytic origin secreted by most cell types present in body fluids [3]. The composition of exosomal cargo is diverse and includes a wide range of immunosuppressive and immune-stimulatory proteins, chemokines, cytokines, cellular receptors, lipids, as well as different nucleic acids such as micro-RNAs [4].

Our previous study [5] showed that MF cell line exosomes carry miR-155 and miR-1246, deliver them to recipient cells and promote cell motility. ExomiR-1246, cell-free miR-155 and cell-free miR-1246 were also upregulated in plasma of patients with MF in correlation to tumor skin burden.

Recent in-vitro studies showed that tumor-derived exosomes (TDE) modulate T-cells which in turn contribute to cancer progression and immune evasion: Lung carcinoma cells delivered exosomal miRNA-214 to T cells downregulate PTEN expression promoting Treg expansion [6]; Pancreatic cancer cell deliver exosomal miRNAs downregulating MAPK1 and JAK/STAT pathways in T cells [7]; Breast cancer cell exosomes suppress T cell proliferation via TGF-β [8]; Melanoma exosomes express PD-L1 on their membrane to suppress CD8+ T cells [9]; Prostate cancer exosomes express membrane FasL to induce Fas-dependent apoptosis of T cells [10,11]. In addition to their direct effects on T cells, tumor exosomes can cause T-cell suppression by affecting myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) [12,13], dendritic cells (DCs) [14–16], and T helper (Th) [17,18].

The objective of this study was to analyze the protein cargo of exosomes derived from MF cell lines and plasma of MF patients, and their effect on chemotherapy resistance, cancer cell viability, and immune cell polarization.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

CTCL cell lines: HH- aggressive peripheral CTCL; Hut78- SS; MyLa- skin MF; and MJ listed by the American tissue culture collection (ATCC) as a peripheral MF cell line that harbors human T-lymphotropic virus (HTLV). MyLa and MJ cells were grown in MDEM, and HH and Hut78 in RPMI, all with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (regular and exosome free by ultracentrifugation), 1% l-glutamine and 1% pen-strep.

Isolation of normal peripheral mononuclear cells (nPBMCs) plasma samples and T cell culturing

Blood samples of patients with pretreated early stage MF (n=6) and healthy controls (n=6) were collected in K3EDTA tubes under the local Helsinki protocol of RMC. Plasma samples were obtained by centrifugation of blood samples at 1000g for 10 min in 4°C and then at 2000g for another 10 min in 4°C.

nPBMCs were separated by Ficoll Hypaque density gradient (Millipore, Burlinton, MA) [19] and resuspended at 1x106 cells/ml in RPMI 1640 medium with 10% human serum (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), followed by the addition of 100U/ml IL2 (PeproTech, Rehovot, Israel) and 50ng/ml anti-CD3 OKT3 (BioLegend, San Diego, CA) for 48 hr and then with 300U/mL IL2 (without OKT3).

Exosome isolation

Exosomes were isolated from supernatant of 4 CTCL cell lines and plasma of early MF patients and healthy individuals. Non-relevant (NR) exosomes were isolated from primary skin fibroblasts obtained from healthy individuals [19]. Exosomes were isolated by differential centrifugation and ultracentrifugation at 4oC. In brief 300 mL of cell-line supernatant (Cell density of 3x105 cells/mL), and 3 mL of human plasma were centrifuged with serial centrifugation. 1300 g for 5 min followed by 2000 g for 10 min were done only for cell-line supernatant. Cell-line supernatant and plasma were then centrifuged as follow: 10,000 g for 30 min; filtration through 0.22 µm; and 90 min at 110,000 g. The exosome pellet was then suspended and centrifuged again at 110,000 g for 90 min. The supernatant was discarded from the exosome pellet, and the pellet was resuspended with the remaining volume of leftover PBS.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

Exosome samples were adsorbed on formvar carbon coated grids and stained with 2% aqueous uranyl acetate and then analyzed by JEM 1400 plus transmission electron microscope (Jeol, Japan).

Nanoparticles tracing analysis (NTA)

Exosome samples were diluted in PBS and analyzed by NanoSight LM10-HS system with a tuned 405 nm laser (NanoSight Ltd., Amesbury, UK).

Exosome internalization assay

Samples of 20 uL of exosomes were mixed with 1.5 mL of Diluent C and 4 µL of the red membrane dye PKH26 (Sigma-Aldrich) and incubated for 10 min. The labelled exosomes were washed twice with PBS at 100,000 g; PBS from the top of the washed labeled exosome tube was used as the control. Thereafter, 5 ´ 105 NPBMCs or MyLa-cells were incubated with labeled exosomes (15 µL) for 24 h. Target cells that internalized the exosomes were analyzed by: 1. Fluorescence microscopy: cells were centrifuged with the Shandon Cytospin® cytocentrifuge; fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde; washed with PBS; and covered with DAPI-Mounting BioLegend. Images were taking with AxioImager Z2 microscope (magnitude x40; Zeiss, Jena, Germany). 2. FACS analysis: cells were washed with PBS and analyzed for PKH26-positive cells by FACS (GalliosTM, Beckman Coulter).

Proteomic content of CTCL cell lines derived exosomes

Exosomes isolated from 4 CTCL cell lines were analyzed by mass spectrometry at the Smoler Proteomics Center in the core facility of the Technion. Exosome samples were boiled, sonicated, precipitated and then digested. The peptides were resolved by reverse-phase chromatography on 0.075 X 200-mm fused silica capillaries (J&W) packed with Reprosil reversed phase material (Dr Maisch GmbH, Germany). The peptides were eluted and Mass spectrometry was performed by a Q-Exactive plus mass spectrometer (QE, Thermo) in a positive mode using repetitively full MS scan followed by High energy Collision Dissociation (HCD) of the 10 most dominant ions selected from the first MS scan. The mass spectrometry data was analyzed using the Protein Discoverer 1.4 software with two search algorithms: Sequest (Thermo) and Mascot (Matrix science), searching against the human proteome from the Uniprot database with mass tolerance of 20 ppm for the precursor masses and 20 ppm for the fragment ions. Peptide- and protein-level false discovery rates (FDRs) were filtered to 1% using the target-decoy strategy. Protein table was filtered to eliminate the identifications from the reverse database, and common contaminants and single peptide identifications. The data was Semi quantified based on extracted ion currents (XICs) of peptides. The area of the protein is the average of the three most intense peptides from each protein.

Detection of exosomal proteins by FACS

Aldehyde Latex FACS beads (Thermo Fisher) were mixed overnight with exosomes at 4°C. The exosome-beads were washed, incubated with 100 mM glycine for 30 min, and then with each one of the following antibodies: CD81-APC (Milteny Biotec, Bergisch); CD44/130-113-904 and OX40/CST-15149S (Miltenyi Biotech); GITR/FAB689V and CXCR4/FAB170G (R&D systems); and CD30/Sc-19658 (Santa Cruz), for 12 min at 4°C. Isotype- matched antibodies were used as a control. The beads were washed and then analyzed by flow cytometer (Gallios).

Immunofluorescence staining for exosomal proteins

Cells were treated with exosomes for 24 h and then cytospined by Shandon Cytospin 3 Cytocentrifuge, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, blocked with Goat blocking serum and incubated for overnight at 4°C with the primary antibodies that were listed above. Secondary antibodies were incubated for 1 h at RT. DAPI-Mounting was added and images were taken by the Axioimager Z2 microscope Zeiss (x40).

MTT cell viability assay

nPBMCs (2×106 cells/ml) and MyLa cells (2×105 cells/ml) were incubated in 96 well-plate with 15 µl of MF-exosomes for 24 h. MTT assay was done and analyzed by ELIZA reader at wavelength of 570 nm with background subtraction at 630–690 nm [19].

Chemo-resistance assay

MyLa cells were treated with MJ-exosomes for 24h, then cells were treated with Doxorubicine (20 nM) (Teva) for another 24 h and with AMD3100 (20 µg/mL) (Sigma). Cell viability assay was done by MTT [19].

Apoptosis assay

Cells (5 ´ 105 cells/mL) were incubated with 15 µl of exosomes for 24 h and stained with fluorescein annexin-V PE and PI. Apoptosis induction=(%apoptotic cells with exosomes)-(% apoptotic cells without exosomes).

Gene expression by quantitative real time PCR (RT-qPCR)

RNA was isolated from MyLa cells and nPBMCs with TRIzol (Ambion, Life Technologies, Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA) and analyzed for gene expression by TaqMan RT-qPCR (Applied Biosystems (ABI), USA) normalized to HPRT1. 5 ng of total RNA was used for reverse cDNA reaction with the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (ABI). For RT-qPCR, we used TaqMan Fast Advanced Master Mix (ABI) on a StepOnePlusTM Real-Time PCR System (ABI).

Mass flow cytometry (CyTOF)

Three million cells were immunostained with a mixture of metal-tagged antibodies which include: antibodies panel A to detect major circulating immune cell subsets (Table S1); and antibodies panel B to detect the expression of immune cell regulators (Table S2). All antibodies were conjugated using the MAXPAR reagent (Fluidigm Inc.). Rhodium and iridium intercalators were used to identify live/dead cells. Cells were washed with PBS, fixed in 1.6% formaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich), washed in ultrapure H2O, and acquired by CyTOF mass cytometry system (DVS Sciences). The analysis of data was performed using Cyto Spanning Tree Progression of Density Normalized Events (SPADE algorithm) on Cytobank database. The percentage of each immune cell subset was defined on combination of immune markers (Table S3).

Data analysis

Differences in the expression level of FOXP3 is demonstrated in -ΔCt and RQ (relative quantification). Non-parametric unpaired Mann-Whitney test was used for the comparisons. For mass cytometry results, the significance of the differential effects among the comparative groups were determined by using one way ANOVA (each sub-population separately) or two ways ANOVA (for groups). *: P<0.05, **: 0.005<p<0.01, ***: p<0.005.

Results

Exosomal protein profile in CTCL

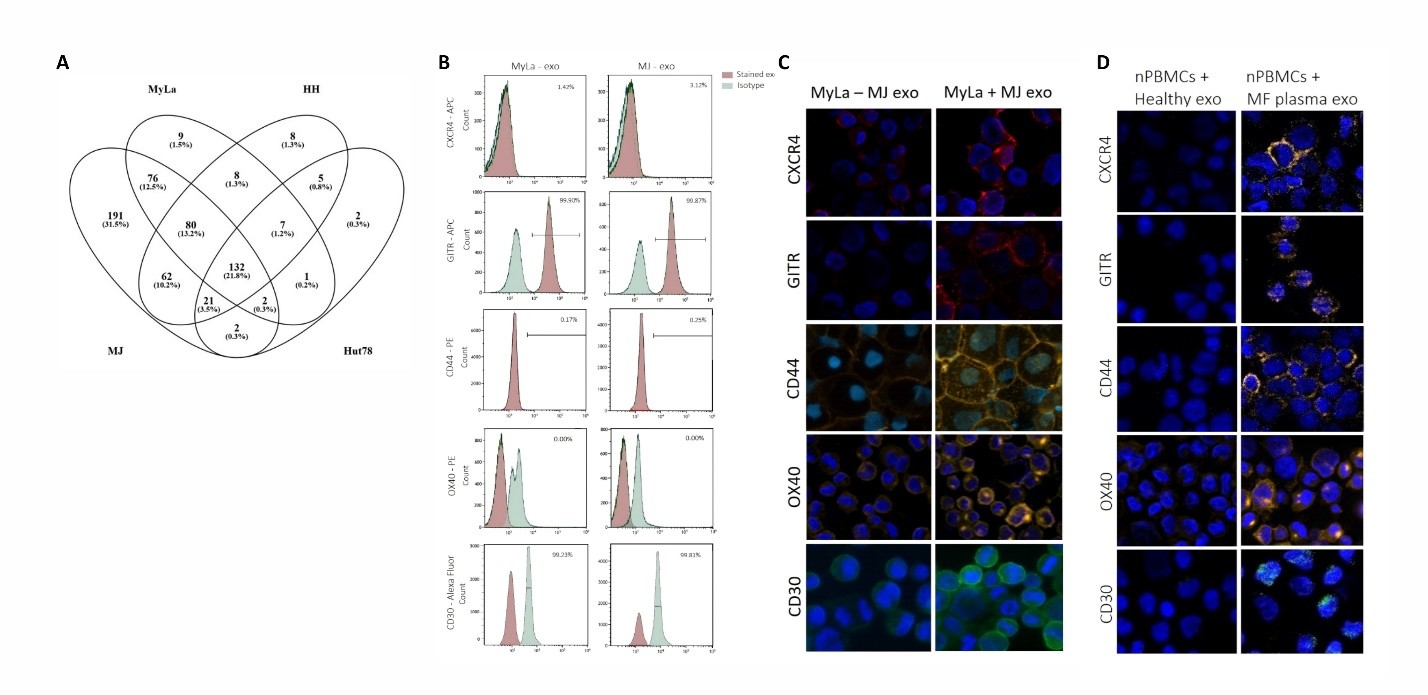

Exosomes were isolated from four CTCL cell lines using serial centrifugation. The isolated exosomes were analyzed for their size concentration and morphology by nanoparticle tracking and electron microscopy (Figures S1 and S2). FACS analysis of CTCL cell-line-derived exosomes revealed high positivity for the exosomal marker CD81 (Between 81% to 98%) (Figure S3), indicating that the isolated EVs were exosome-enriched. Mass spectrometry, employed for a comprehensive proteomic analysis, detected a total of 566 proteins in MJ-exosomes, 315 in MyLa-exosomes, 323 in HH-exosomes, and 172 in Hut78-exosomes (Figure 1A). The presence of VCP protein (Transitional endoplasmic reticulum ATPase), a known exosomal membrane-enriched protein, was observed in exosomes derived from all 4 CTCL cell lines, indicating the presence of exosomal content.

Figure 1. The proteomic content and delivery of exosomes derived from CTCL cell lines. Venn diagram depicting the overlapping proteins identified in exosomes derived from four CTCL cell lines using mass spectrometry (A). FACS analysis of CXCR4, GITR, CD44, OX40, and CD30, along with their matched isotype controls, in MJ- and MyLa-exosomes conjugated to beads (B). Immunostaining of MyLa cells incubated with MJ-exosomes to monitor the internalization of exosomal CXCR4, GITR, CD44, CD30, and OX40 (C). Immunostaining of T-cell culture incubated with exosomes from plasma of MF patients, compared to plasma from healthy donors, to detect the uptake of CXCR4, GITR, CD44, and CD30 (D).

To assess the purity of our exosome isolates, we evaluated markers of common contaminants, including intracellular organelles and lipoproteins. Calnexin (ER), GM130 (Golgi), Cytochrome C (mitochondria), and histones (nuclear) were undetectable by mass spectrometry proteomic analysis, confirming minimal contamination from intracellular organelles and other EVs. Low but detectable levels of ApoA1 and ApoB were present in our exosome samples despite the use of exosome-depleted FBS, likely reflecting trace residual lipoproteins from the FBS-EVs.

Among the CTCL cell lines, MJ-exosomes exhibited 36 cancer related proteins 19 of them were also expressed by MyLa-exosomes. Among these 19 shared exosomal proteins, 4 immune checkpoint proteins: ICOS, OX40, GITR, and CD47 were uniquely expressed in MF exosomes (MyLa and MJ). CXCR4 [20] was also uniquely expressed in MF exosomes, while CD44 [21,22] and CD30 [23] were also expressed in exosomes from other CTCL cell lines. FACS analysis was performed to identify exosomal membrane proteins, demonstrating positive staining for GITR and CD30, while the other 3 proteins (CXCR4, OX40, CD44) showed negative staining, suggesting they are intra-exosomal proteins (Figure 1B).

MJ cell line is derived from the peripheral lymphoma cells of a patient with MF, and represents invasive high-grade MF cells, whereas MyLa cell line is skin MF cells representing localized low-grade cells. Therefore, we studied the effect of MJ-exosomes on MyLa cells as part of the intercellular communication in tumor heterogeneity.

We observed some cytoplasmic foci of OX40, CXCR4, GITR, CD44, and CD30 in MyLa cells incubated with MJ-exosomes which was absent in MyLa cells without exosomes, confirming the presence and transfer of those exosomal proteins (Figure 1C). Exosomes were isolated from plasma samples of MF patients and healthy donors and confirmed for their size and concentration by Nanoparticle tracking (Figure S4). Normal T-cell cultures obtained from nPBMCs of healthy volunteers treated with exosomes from MF patients demonstrated cytoplasmic foci of positive immunostaining for OX40, CXCR4, GITR, CD44, and CD30 (Figure 1D). In contrast, normal T-cell cultures treated with exosomes derived from healthy donors’ exosomes failed to show the foci staining of those proteins.

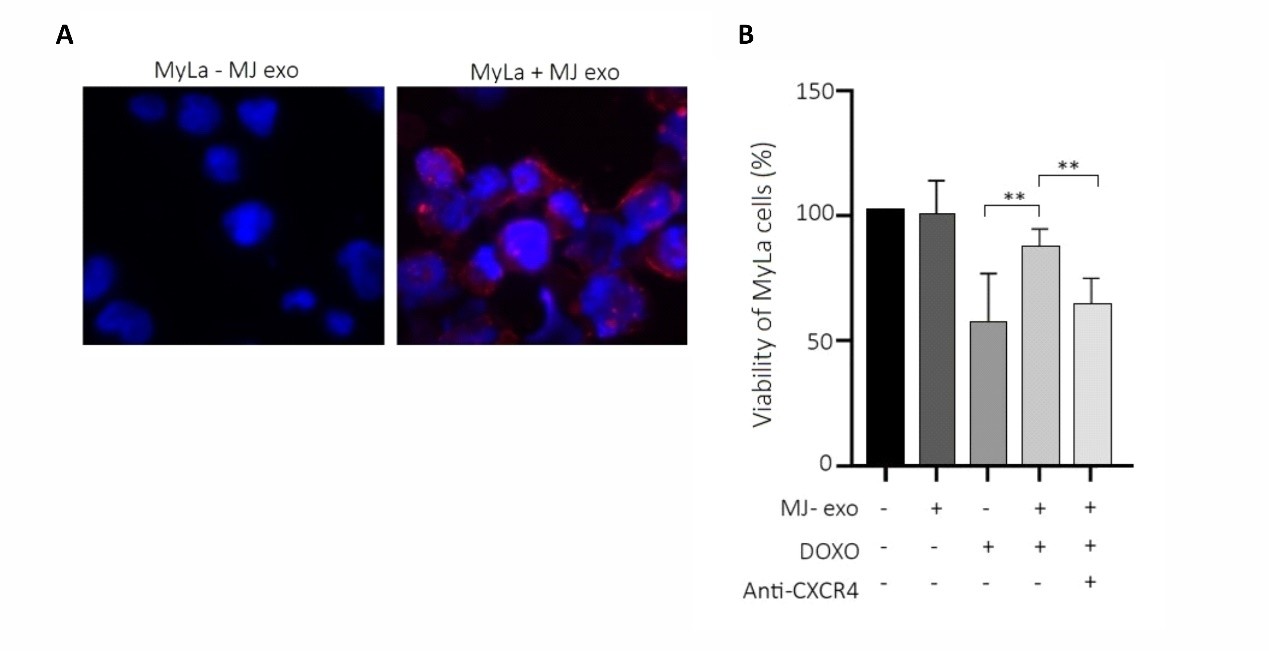

MJ-exosomes mediate chemo-resistance in MyLa cells via CXCR4-mediated signaling

To investigate whether MJ-exosomes affect the chemo-resistance of MyLa cells, we first tracked the uptake of MJ-exosomes into MyLa cells using stained exosomes with PKH26 dye (Figure 2A). Subsequently, MTT viability assay of MyLa cells pre-incubated with MJ-exosomes and treated with Doxorubicin showed a significant increase (37%) in the viability of MyLa cells with MJ-exosomes vs without (p=0.0069) (Figure 2B). Given that CXCR4 inhibitor has been reported to sensitize cells to chemotherapy [24–26], we investigated whether CXCR4 is involved in the MJ-exosomes mediating resistance to Doxorubicin. We saw that CXCR4 antagonist (AMD3100) reduced the chemo-protective effect of MJ-exosomes on MyLa cells, resulting in a decrease in cell survival following Doxorubicin treatment 76.3% (-AMD3100) vs. 56.6% (+AMD3100), (p=0.0097) (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Uptake of MJ-exosomes by MyLa cells and their impact on resistance to Doxorubicin-induced cell death. Immunostaining of the exosomal marker CD81 in MyLa cells following a 24 h incubation with MJ-exosomes (magnification x40) (A). Viability assay using MTT of MyLa cells treated with or without MJ-exosomes for 24 h, followed by treatment with 20 nM Doxorubicin for an additional 24 h, with and without the CXCR4 inhibitor AMD3100 (20 µg/mL) (B).

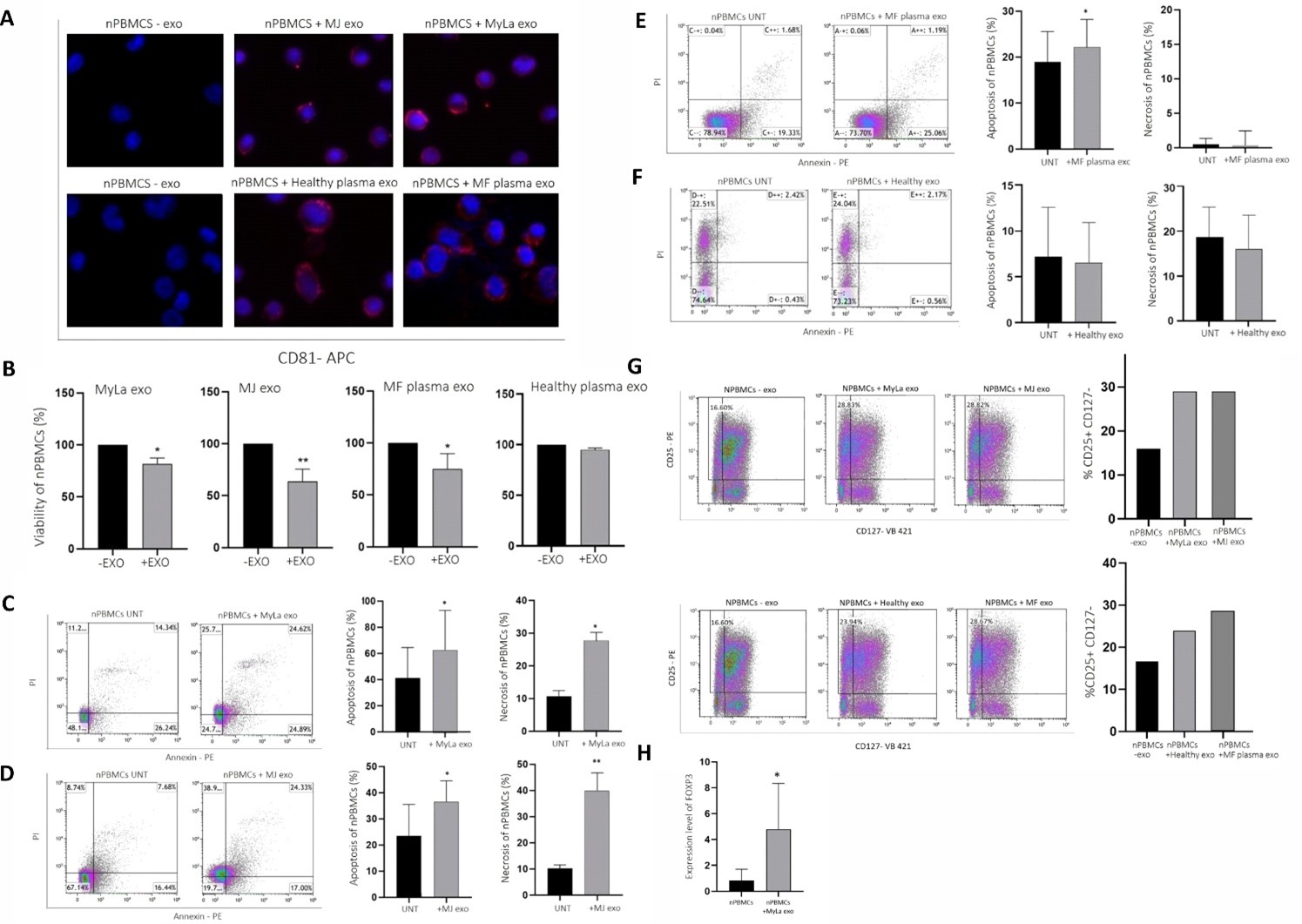

MF-exosomes induce T-cell death via apoptosis and necrosis

The ability to evade immune system is a major hallmark of cancer [27]. Therefore, we evaluated the effect of MF-exosomes on the viability of T-cell culture. We incubated T-cell culture with exosomes from: MF cell lines, plasma of MF patients and plasma of healthy donors. The T-cells were stained for CD81 and analyzed in MTT viability assay. The immunostaining revealed a characteristic cytoplasmic CD81 dot staining indicative for the uptake of exosomes derived from MF cell lines as well as plasma of MF patients and healthy controls (Figure 3A). The viability assay demonstrated that MF-exosomes, both from patient plasma and cell lines, significantly reduced the viability of the T-cells compared to exosomes from healthy donor plasma (Figure 3B). Specifically, the viability of the T-cells was reduced to 89% with MyLa-exosomes (p=0.0242), 63.6% with MJ-exosomes (p=0.0069), and 75% with exosomes derived from plasma of MF patients (p=0.0175) compared to cells without exosomes (Figure 3B). In contrast, exosomes of healthy donors didn’t affect the viability of T-cells with 96% live cells and p=0.0728 in comparison to cells without exosomes (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. Exosomes derived from MF (cell lines and patients' plasma) decrease the viability of T cells and promote polarization of Tregs. Immunostaining of the exosomal marker CD81 in T cell culture incubated for 24 h with exosomes derived from MF cell lines, plasma of MF patients or plasma of healthy donors (magnification x40) (A). The viability of the T cell culture, as determined by MTT assay was compared between cultures incubated with exosomes from MF cell lines, patients' plasma, and healthy donors' plasma, and cells without exosomes (B). Apoptosis and necrosis in the T-cell culture were assessed by FACS analysis of annexin V and PI staining, comparing the effects of exosomes derived from MyLa (C), MJ (D), plasma of MF patients (E), and plasma of healthy donors (F) to cells without exosomes. The frequency of CD25+CD127- cells in the T-cell culture was analyzed by FACS, comparing cultures with or without exosomes from MJ, MyLa, plasma of MF patients, and plasma of healthy donors (G). RT-qPCR was performed to measure the expression of FOXP3 in the T-cell culture with or without MyLa-exosomes (H).

FACS analysis of annexin V and propidium iodide staining showed a significant increase in the apoptosis and necrosis of cells with MF-exosomes compared to cells without exosomes as follows: 8.93% induction of apoptosis (p=0.0258) and 14.75% induction of necrosis (p=0.0157) with MyLa-exosomes (Figure 3C); 17.21% induction of apoptosis (p=0.0186) and 30.16% induction of necrosis (p=0.0023) with MJ-exosomes (Figure 3D); and 7.46% induction of apoptosis with exosomes derived from plasma of MF patients (p=0.0395) (Figure 3E). Importantly, plasma exosomes from healthy donors had no apoptotic (p=0.07292) or necrotic (p=0.0852) effects on the viability of T-cells (Figure 3F). These results provide evidence that MF-exosomes promote death of T-cells through apoptosis and necrosis.

MF-exosomes promote expansion of Tregs

Since we identified GITR, which is a known Treg expansion factor [28], we hypothesized that MF exosomes might facilitate the polarization of T cells to Tregs. T-cell cultures were analyzed by FACS for the percent of CD25+CD127- (Treg markers) after 24 h of incubation with and without the following exosomes: MF cell line exosomes (Figure 3G upper panel); plasma exosomes of MF patients and healthy donors (Figure 3G lower panel). The percent of CD25+CD127- cells incubated with MF-exosomes (derived from MyLa, MJ, and MF patients plasma) was higher (28.82%, 28.83%, 28.67%, respectively) than cells with plasma exosomes from healthy donors (23.94%) and cells without exosomes (16.60%).

Furthermore, the expression level of FOXP3, a transcription marker of Tregs [29,30] in the T-cells incubated with MyLa-exosomes increased within 4.79 folds compared to cells without exosomes (p=0.0286) (Figure 3H).

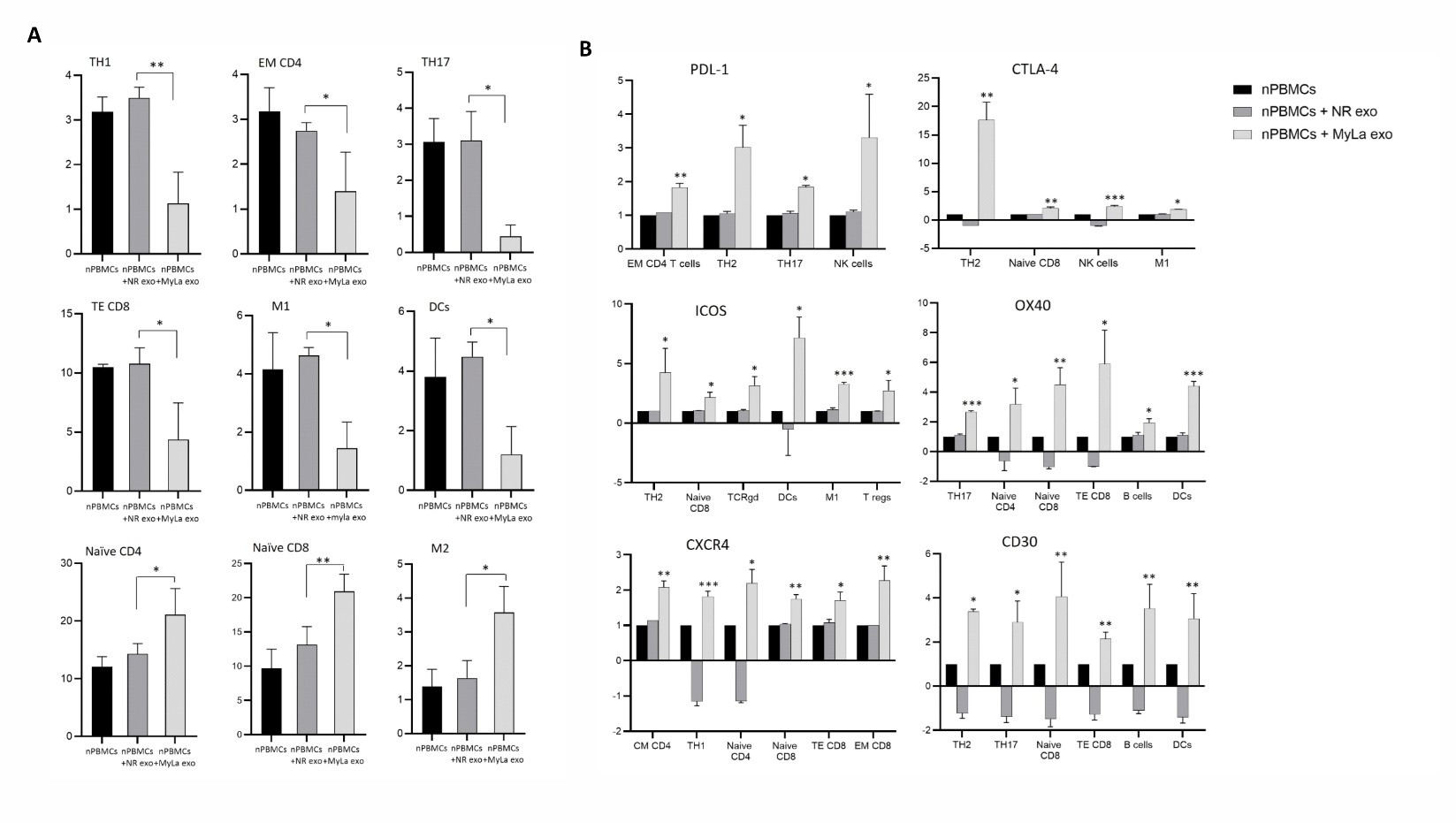

MyLa-exosomes modulate immune cell polarization and regulate the expression of specific immune checkpoint proteins, promoting a suppressed phenotype

We conducted an exploratory analysis using CyTOF on nPBMCs obtained from healthy donors. A panel of 41 antibodies were carefully selected to comprehensively analyze diverse immune cell populations and immune regulators. nPBMCs were incubated with MyLa exosomes, while non-relevant (NR) exosomes were used as a control. The CyTOF experiment was repeated twice with two different samples of fresh nPBMCs obtained from two different donors. Utilizing antibody panel A (markers for identifying specific subsets of immune cells), we observed a significant decrease in the percentage of Th1, effector memory (EM) CD4 T cells, Th17, T effector (TE) CD8 T cells, M1, and dendritic cells (DC) subsets upon incubation with MF exosomes compared to the NR-exosomes (p=0.0229, 0.0269, 0.0376, 0.009, 0.0358, 0.0244, respectively). In contrast, we detected an increase in the percentage of M2, Naïve CD4 and Naïve CD8 T cells upon incubation with MyLa exosomes vs NR-exosomes (p=0.0063, 0.0402, 0.0262, respectively) (Figure 4A). Based on antibody panel B (immune checkpoint proteins and immune regulators), we found a significant increase in the expression level of three immune checkpoint proteins in nPBMCs upon incubation with MF exosomes, vs without exosomes (Table S2). Programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression was upregulated in EM CD4+ T cells, Th2, Th17, and natural killer (NK) cells (p=0.0027, 0.0213, 0.0314, 0.0267, respectively) (Figure 4B). ICOS was upregulated in Th2, Naïve CD8 T, TCRgd cells, DCs, M1 cells and Treg cells (p=0.0227, 0.0353, 0.025, 0.0341, 0.0008, 0.019, respectively) (Figure 4B). CTLA-4 was increased in Th2, Naïve CD8 T cells, NK cells and M1 (p=0.0036, 0.0076, 0.0002, 0.0357, respectively) (Figure 4B). OX40 was increased in Th17, Naïve CD4, Naïve CD8, TE CD8, B cells and DCs (p=0.0001, 0.028, 0.008, 0.0279, 0.0247, 0.0007, respectively) (Figure 4B). Notably, the NR-exosomes did not affect the expression of those proteins in the nPBMCs.

Two proteins related to MF, CXCR4 and CD30 were upregulated upon incubation with MF exosomes. CXCR4 was upregulated in central memory CD4, Th1, Naïve CD4, Naïve CD8, TE CD8, EM CD8 (p=0.0042, 0.0003, 0.0209, 0.0029, 0.0247, 0.0033, respectively). CD30 was upregulated in Th2, Th17, Naïve CD8, TE CD8, B cells and DCs (p=0.0125, 0.0102, 0.0044, 0.0016, 0.002, 0.0031, respectively) (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. Comprehensive immune characterization of nPBMCs with and without MyLa-exosomes. Multiplexed single-cell flow mass cytometry for quantification of immune cell populations and expression of immune regulator proteins in nPBMCs with and without MyLa exosomes: the percent of several immune cell populations (A); expression of immune regulator proteins in specific immune cell subsets (B).

Discussion

Our study represents the first investigation into the protein cargo of MF-exosomes and their relevance to MF. By using exosomes derived from the only two MF cell lines and confirming the findings on exosomes from plasma of MF patients, we found that they deliver unique immune regulator proteins. These exosomes protect target cells from chemotherapy through exosomal CXCR4, mediate apoptosis of T cells, reduce Th1 and M2 populations, and increase Treg, Th2, and M1 populations along with increased expression of PD-L1.

Herein, we found that CXCR4 is abundant in MF-exosomes and is delivered into target cells and increased its expression on target cell membrane. Furthermore, exosomes derived from a high-grade MF cell line protect low-grade MF cell line from Doxorubicin in CXCR4 dependent manner. Previous studies showed that CXCR4 is overexpressed in several cancer types, including MF, and in correlation with chemo-protective properties [31–33].

MF-exosomal CXCR4 protects recipient cells from chemotherapy, and blockade of CXCR4 with AMD3100 reverses this exosome-mediated chemoresistance. Thus, the CXCR4–CXCL12-driven pro-survival signaling mediated by MF exosomes, highlight exosomal CXCR4 as a rational therapeutic target for combining CXCR4 antagonists with chemotherapy in MF to overcome MF-exosome-mediate chemoresistance.

We suggest that in order to overcome tumor heterogeneity of MF [34], MF-exosomal CXCR4 protect recipient cells from chemotherapy, induce their migration and invasion as was shown for other cancers [35,36], and even might recruit intratumoral reactive immune cells through CXCR4 mediated chemotaxis and direct them for immunosuppression [37,38].

Tumor-associated Tregs have been extensively studied in various malignancies [39,40], including CTCL [42–44]. TDE are known to enhance Treg and Breg proliferation and function [44–48]. We found that MF-exosomes expand Treg population and induce the expression of FOXP3, a key transcription factor associated with Tregs. Moreover, exosomes obtained from MF cell lines and plasma of MF patients, but not from healthy donors, reduced the viability and induced apoptosis of T-cells, suggesting another regulatory pathway of immune suppression mediated by MF-exosomes.

The CyTOF analysis demonstrated that MF-exosomes promote immune cell remodeling by cell polarization and regulating the expression of immune regulators. We found a substantial decrease in the proportion of Th1, EM CD4 T and CD8 TE cells following the treatment of MF-exosomes, assuming that MF-exosomes contribute to the downregulation of T cell responses against MF cells. We also observed a decrease in M1 cells and an accumulation of M2 cells upon MF-exosomes, which is in line with the known predominance of M2 cells in MF human tissues and murine models [49–55].

DC are the most important and effective APCs that orchestrate immune responses by priming naive T-cells and providing subsequent signals required for the activity of effector T-cells [56]. Studies have indicated that the tumor microenvironment (TEM) in MF disrupts the maturation and activation of DCs [57]. Our analysis revealed a decrease in the percentage of DCs in nPBMCs incubated with MF-exosomes, suggesting a novel exosome-mediated mechanism that hampers the activation of tumor-infiltrating T-cells. Similarly, TDE of other types of malignancies have already been shown to promote an immature DCs phenotype [58,59].

Our most significant finding is the upregulation of PD-L1 in T-cells, NK cells, and macrophages. TDE can inhibit anti-tumor immunity via the delivery of variety components such as miRNAs, noncoding RNAs and members of STAT3 pathway, which mediate an indirect upregulation of PD-L1 on various immune cells within the TEM [60–64]. Since our proteomic analysis did not identify the presence of PD-L1 in MF exosomes, we assume that the upregulation of PD-L1 in immune cells is due to delivery of exosomal microRNAs, which negatively regulate PD-L1 expression. MF tissue samples showed a predominance of immature DCs over mature ones [65,66], and direct contact with immature DCs promotes MF cell proliferation and MF cell production of IL-10 maintains long-term DCs immaturity which may promote a T-cell exhausted phenotype within the CTCL microenvironment [67–71]. We detected a decrease in DC population due to MF-exosomes but with increased expression of ICOS and OX40. Studies have revealed that benign T-cells, MF cells and Tregs of MF patients showed increases in OX40 and ICOS proteins [72,73] with strong association to Th2 [74]. We observed an upregulation of OX40 and ICOS in many subsets of immune cells, which might indicate for non-specific exosome uptake in T-cell culture which might differ from the in vivo machinery in the TEM of MF biopsies.

In addition to PD-L1 upregulation mediated by MF-derived exosomes, we also observed upregulation of CTLA-4 on immune cells. These MF-derived exosome effects create a dual checkpoint-mediated immune escape mechanism. This dual immunosuppressive pathway, and each single pathway individually, can be therapeutically targeted through two complementary strategies: (1) single or dual checkpoint blockade using anti-PD-L1 and/or anti-CTLA-4 antibodies to relieve T-cell exhaustion, and (2) combination therapy with exosome secretion inhibitors and checkpoint inhibitors to eliminate systemic immunosuppression by circulating MF exosomes and thereby improve immunotherapy response rates in MF.

CD30 is a member of the tumor necrosis factor family expressed on diverse hematologic malignancies [75,76], including CTCL [77]. Its expression in MF seems to be associated with advanced disease stage and large-cell transformation [77]. The upregulation of CD30 in the immune cell subset observed in our study might be associated with inhibition of T-cell activity or represents an optional internalization into lymphoma cells to drive anti-apoptotic and anti-proliferative signals [78–80].

Conclusions

Our study presents the first evidence indicating that MF cells release exosomes for mediating a tumor-favoring environment, marked by immune cell polarization and suppression. MF-exosomes: induce T-cell apoptosis; expand FOXP3+ regulatory T cells; shift macrophages toward an immunosuppressive M2 state; decrease effector cells (Th1, EM CD4+, TE CD8+, DC) and upregulate PD-L1/CTLA-4 on immune cells, driving immune evasion. Simultaneously, these exosomes transport oncogenic cargo within lymphoma cells, encouraging tumor survival and chemoresistance.

Acknowledgements

We thank: Amir Grau from the Cytometry Center at the Rappaport Faculty of Medicine Biomedical Core Facility, Technion, Israel, for his excellent support with the CYTOF technology; Tamar Ziv from the Smoler proteomics Center at the life Sciences and Engineering, Technion, Israel, for her excellent support with the proteomic profiling.

Funding

This study had no funding support.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, L.M, upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

2. Weinstock MA, Gardstein B. Twenty-year trends in the reported incidence of mycosis fungoides and associated mortality. Am J Public Health. 1999 Aug;89(8):1240–4.

3. Akers JC, Gonda D, Kim R, Carter BS, Chen CC. Biogenesis of extracellular vesicles (EV): exosomes, microvesicles, retrovirus-like vesicles, and apoptotic bodies. J Neurooncol. 2013 May;113(a):1–11.

4. Yin Z, Yu M, Ma T, Zhang C, Huang S, Karimzadeh MR, et al. Mechanisms underlying low-clinical responses to PD-1/PD-L1 blocking antibodies in immunotherapy of cancer: a key role of exosomal PD-L1. J Immunother Cancer. 2021 Jan 20;9(1):e001698.

5. Moyal L, Arkin C, Gorovitz-Haris B, Querfeld C, Rosen S, Knaneh J, et al. Mycosis fungoides-derived exosomes promote cell motility and are enriched with microRNA-155 and microRNA-1246, and their plasma-cell-free expression may serve as a potential biomarker for disease burden. Br J Dermatol. 2021 Nov;185(5):999–1012.

6. Yin Y, Cai X, Chen X, Liang H, Zhang Y, Li J, et al. Tumor-secreted miR-214 induces regulatory T cells: a major link between immune evasion and tumor growth. Cell Res. 2014 Oct;24(10):1164–80.

7. Ye SB, Li ZL, Luo DH, Huang BJ, Chen YS, Zhang XS, et al. TDE promote tumor progression and T-cell dysfunction through the regulation of enriched exosomal microRNAs in human nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2014 Jul 30;5(14):5439–52.

8. Rong L, Li R, Li S, Luo R. Immunosuppression of breast cancer cells mediated by transforming growth factor-β in exosomes from cancer cells. Oncol Lett. 2016 Jan;11(1):500–04.

9. Chen G, Huang AC, Zhang W, Zhang G, Wu M, Xu W, et al. Exosomal PD-L1 contributes to immunosuppression and is associated with anti-PD-1 response. Nature. 2018 Aug;560(7718):382–386.

10. Abusamra AJ, Zhong Z, Zheng X, Li M, Ichim TE, Chin JL, et al. Tumor exosomes expressing Fas ligand mediate CD8+ T-cell apoptosis. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2005 Sep-Oct;35(2):169–73.

11. Andreola G, Rivoltini L, Castelli C, Huber V, Perego P, Deho P, et al. Induction of lymphocyte apoptosis by tumor cell secretion of FasL-bearing microvesicles. J Exp Med. 2002 May 20;195(10):1303–16.

12. Chalmin F, Ladoire S, Mignot G, Vincent J, Bruchard M, Remy-Martin JP, et al. Membrane-associated Hsp72 from tumor-derived exosomes mediates STAT3-dependent immunosuppressive function of mouse and human myeloid-derived suppressor cells. J Clin Invest. 2010 Feb;120(2):457–71.

13. Gabrusiewicz K, Li X, Wei J, Hashimoto Y, Marisetty AL, Ott M, et al. Glioblastoma stem cell-derived exosomes induce M2 macrophages and PD-L1 expression on human monocytes. Oncoimmunology. 2018 Jan 16;7(4):e1412909.

14. Salimu J, Webber J, Gurney M, Al-Taei S, Clayton A, Tabi Z. Dominant immunosuppression of dendritic cell function by prostate-cancer-derived exosomes. J Extracell Vesicles. 2017 Sep 3;6(1):1368823.

15. Tucci M, Mannavola F, Passarelli A, Stucci LS, Cives M, Silvestris F. Exosomes in melanoma: a role in tumor progression, metastasis and impaired immune system activity. Oncotarget. 2018 Apr 17;9(29):20826–37.

16. Ning Y, Shen K, Wu Q, Sun X, Bai Y, Xie Y, et al. Tumor exosomes block dendritic cells maturation to decrease the T cell immune response. Immunol Lett. 2018 Jul;199:36–43.

17. Guo D, Chen Y, Wang S, Yu L, Shen Y, Zhong H, et al. Exosomes from heat-stressed tumour cells inhibit tumour growth by converting regulatory T cells to Th17 cells via IL-6. Immunology. 2018 May;154(1):132–43.

18. Huang F, Wan J, Hao S, Deng X, Chen L, Ma L. TGF-β1-silenced leukemia cell-derived exosomes target dendritic cells to induce potent anti-leukemic immunity in a mouse model. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2017 Oct;66(10):1321–31.

19. Aronovich A, Moyal L, Gorovitz B, Amitay-Laish I, Naveh HP, Forer Y, et al. Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts in Mycosis Fungoides Promote Tumor Cell Migration and Drug Resistance through CXCL12/CXCR4. J Invest Dermatol. 2021 Mar;141(3):619–627.e2.

20. Maj J, Jankowska-Konsur AM, Hałoń A, Woźniak Z, Plomer-Niezgoda E, Reich A. Expression of CXCR4 and CXCL12 and their correlations to the cell proliferation and angiogenesis in mycosis fungoides. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2015 Dec;32(6):437–42.

21. Wagner SN, Wagner C, Reinhold U, Funk R, Zöller M, Goos M. Predominant expression of CD44 splice variant v10 in malignant and reactive human skin lymphocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 1998 Sep;111(3):464–71.

22. Liang X, Smoller BR, Golitz LE. Expression of CD44 and CD44v6 in primary cutaneous CD30 positive T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders. J Cutan Pathol. 2002 Sep;29(8):459–64.

23. Wieser I, Tetzlaff MT, Torres Cabala CA, Duvic M. Primary cutaneous CD30(+) lymphoproliferative disorders. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2016 Aug;14(8):767–82.

24. Righi E, Kashiwagi S, Yuan J, Santosuosso M, Leblanc P, Ingraham R, et al. CXCL12/CXCR4 blockade induces multimodal antitumor effects that prolong survival in an immunocompetent mouse model of ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2011 Aug 15;71(16):5522–34.

25. Chen Y, Ramjiawan RR, Reiberger T, Ng MR, Hato T, Huang Y, et al. CXCR4 inhibition in tumor microenvironment facilitates anti-programmed death receptor-1 immunotherapy in sorafenib-treated hepatocellular carcinoma in mice. Hepatology. 2015 May;61(5):1591–602.

26. Zeng Y, Li B, Liang Y, Reeves PM, Qu X, Ran C, et al. Dual blockade of CXCL12-CXCR4 and PD-1-PD-L1 pathways prolongs survival of ovarian tumor-bearing mice by prevention of immunosuppression in the tumor microenvironment. FASEB J. 2019 May;33(5):6596–6608.

27. Cavallo F, De Giovanni C, Nanni P, Forni G, Lollini PL. 2011: the immune hallmarks of cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2011 Mar;60(3):319–26.

28. van Beek AA, Zhou G, Doukas M, Boor PPC, Noordam L, Mancham S, et al. GITR ligation enhances functionality of tumor-infiltrating T cells in hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2019 Aug 15;145(4):1111–24.

29. Qiu Y, Ke S, Chen J, Qin Z, Zhang W, Yuan Y, et al. FOXP3+ regulatory T cells and the immune escape in solid tumours. Front Immunol. 2022 Oct 13;13:982986.

30. Saleh R, Elkord E. FoxP3+ T regulatory cells in cancer: Prognostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets. Cancer Lett. 2020 Oct 10;490:174–85.

31. Domanska UM, Kruizinga RC, Nagengast WB, Timmer-Bosscha H, Huls G, de Vries EG, Walenkamp AM. A review on CXCR4/CXCL12 axis in oncology: no place to hide. Eur J Cancer. 2013 Jan;49(1):219–30.

32. Chatterjee S, Behnam Azad B, Nimmagadda S. The intricate role of CXCR4 in cancer. Adv Cancer Res. 2014; 124:31–82.

33. Hu X, Mei S, Meng W, Xue S, Jiang L, Yang Y, et al. CXCR4-mediated signaling regulates autophagy and influences acute myeloid leukemia cell survival and drug resistance. Cancer Lett. 2018 Jul 1; 425:1–12.

34. GAYDOSIK, Alyxzandria M., et al. Single-Cell Lymphocyte Heterogeneity in Advanced Cutaneous T-cell Lymphoma Skin TumorsSingle Cell Heterogeneity in CTCL Skin Tumors. Clinical Cancer Research, 2019, 25.14: 4443–54.

35. Zhang S, Zhang Y, Qu J, Che X, Fan Y, Hou K, et al. Exosomes promote cetuximab resistance via the PTEN/Akt pathway in colon cancer cells. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2017 Nov 13;51(1):e6472.

36. Min QH, Wang XZ, Zhang J, Chen QG, Li SQ, Liu XQ, et al. Exosomes derived from imatinib-resistant chronic myeloid leukemia cells mediate a horizontal transfer of drug-resistant trait by delivering miR-365. Exp Cell Res. 2018 Jan 15;362(2):386–93.

37. Gerratana L, Toffoletto B, Bulfoni M, Cesselli D, Beltrami AP, Di Loreto C, et al. Metastatic breast cancer and circulating exosomes. Hints from an exploratory analysis. Ann Oncol. 2015 Oct 1;26:vi14.

38. Li N, Wang Y, Xu H, Wang H, Gao Y, Zhang Y. Exosomes Derived from RM-1 Cells Promote the Recruitment of MDSCs into Tumor Microenvironment by Upregulating CXCR4 via TLR2/NF-κB Pathway. J Oncol. 2021 Oct 8;2021:5584406.

39. Iglesias-Escudero M, Arias-González N, Martínez-Cáceres E. Regulatory cells and the effect of cancer immunotherapy. Mol Cancer. 2023 Feb 4;22(1):26.

40. Paluskievicz CM, Cao X, Abdi R, Zheng P, Liu Y, Bromberg JS. T Regulatory Cells and Priming the Suppressive Tumor Microenvironment. Front Immunol. 2019 Oct 15;10:2453.

41. Berger CL, Tigelaar R, Cohen J, Mariwalla K, Trinh J, Wang N, et al. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: malignant proliferation of T-regulatory cells. Blood. 2005 Feb 15;105(4):1640–7.

42. Wada DA, Wilcox RA, Weenig RH, Gibson LE. Paucity of intraepidermal FoxP3-positive T cells in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma in contrast with spongiotic and lichenoid dermatitis. J Cutan Pathol. 2010 May;37(5):535–41.

43. Shalabi D, Bistline A, Alpdogan O, Kartan S, Mishra A, Porcu P, et al. Immune evasion and current immunotherapy strategies in mycosis fungoides (MF) and Sézary syndrome (SS). Chin Clin Oncol. 2019 Feb;8(1):11.

44. Ma F, Vayalil J, Lee G, Wang Y, Peng G. Emerging role of tumor-derived extracellular vesicles in T cell suppression and dysfunction in the tumor microenvironment. J Immunother Cancer. 2021 Oct;9(10):e003217.

45. Valenti R, Huber V, Iero M, Filipazzi P, Parmiani G, Rivoltini L. Tumor-released microvesicles as vehicles of immunosuppression. Cancer Res. 2007 Apr 1;67(7):2912–5.

46. Szajnik M, Czystowska M, Szczepanski MJ, Mandapathil M, Whiteside TL. Tumor-derived microvesicles induce, expand and up-regulate biological activities of human regulatory T cells (Treg). PLoS One. 2010 Jul 22;5(7):e11469.

47. Filipazzi P, Bürdek M, Villa A, Rivoltini L, Huber V. Recent advances on the role of tumor exosomes in immunosuppression and disease progression. Semin Cancer Biol. 2012 Aug;22(4):342–9.

48. Qu JL, Qu XJ, Zhao MF, Teng YE, Zhang Y, Hou KZ, et al. The role of cbl family of ubiquitin ligases in gastric cancer exosome-induced apoptosis of Jurkat T cells. Acta Oncol. 2009;48(8):1173–80.

49. Stolearenco V, Namini MRJ, Hasselager SS, Gluud M, Buus TB, Willerslev-Olsen A, et al. Cellular Interactions and Inflammation in the Pathogenesis of Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020 Sep 4;8:851.

50. Krejsgaard T, Lindahl LM, Mongan NP, Wasik MA, Litvinov IV, Iversen L, et al. Malignant inflammation in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma-a hostile takeover. Semin Immunopathol. 2017 Apr;39(3):269-282.

51. Pettersen JS, Fuentes-Duculan J, Suárez-Fariñas M, Pierson KC, Pitts-Kiefer A, Fan L, et al. Tumor-associated macrophages in the cutaneous SCC microenvironment are heterogeneously activated. J Invest Dermatol. 2011 Jun;131(6):1322–30.

52. Sugaya M, Miyagaki T, Ohmatsu H, Suga H, Kai H, Kamata M, et al. Association of the numbers of CD163(+) cells in lesional skin and serum levels of soluble CD163 with disease progression of cutaneous T cell lymphoma. J Dermatol Sci. 2012 Oct;68(1):45–51.

53. Wu X, Schulte BC, Zhou Y, Haribhai D, Mackinnon AC, Plaza JA, et al. Depletion of M2-like tumor-associated macrophages delays cutaneous T-cell lymphoma development in vivo. J Invest Dermatol. 2014 Nov;134(11):2814–22.

54. Furudate S, Fujimura T, Kakizaki A, Kambayashi Y, Asano M, Watabe A, et al. The possible interaction between periostin expressed by cancer stroma and tumor-associated macrophages in developing mycosis fungoides. Exp Dermatol. 2016 Feb;25(2):107–12.

55. Assaf C, Hwang ST. Mac attack: macrophages as key drivers of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma pathogenesis. Exp Dermatol. 2016 Feb;25(2):105–6.

56. Motta JM, Rumjanek VM. Sensitivity of Dendritic Cells to Microenvironment Signals. J Immunol Res. 2016; 2016:4753607.

57. Stolearenco V, Namini MRJ, Hasselager SS, Gluud M, Buus TB, Willerslev-Olsen A, et al. Cellular Interactions and Inflammation in the Pathogenesis of Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020 Sep 4;8:851.

58. Benites BD, Alvarez MC, Saad STO. Small Particles, Big Effects: The Interplay Between Exosomes and Dendritic Cells in Antitumor Immunity and Immunotherapy. Cells. 2019 Dec 16;8(12):1648.

59. Hosseini R, Asef-Kabiri L, Yousefi H, Sarvnaz H, Salehi M, Akbari ME, et al. The roles of tumor-derived exosomes in altered differentiation, maturation and function of dendritic cells. Mol Cancer. 2021 Jun 2;20(1):83.

60. Liu J, Fan L, Yu H, Zhang J, He Y, Feng D, et al. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Causes Liver Cancer Cells to Release Exosomal miR-23a-3p and Up-regulate Programmed Death Ligand 1 Expression in Macrophages. Hepatology. 2019 Jul;70(1):241–258.

61. Haderk F, Schulz R, Iskar M, Cid LL, Worst T, Willmund KV, et al. TDE modulate PD-L1 expression in monocytes. Sci Immunol. 2017 Jul 28;2(13):eaah5509.

62. Yin Y, Liu B, Cao Y, Yao S, Liu Y, Jin G, et al. Colorectal Cancer-Derived Small Extracellular Vesicles Promote Tumor Immune Evasion by Upregulating PD-L1 Expression in Tumor-Associated Macrophages. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2022 Jan 17;9(9):2102620.

63. Cheng L, Liu J, Liu Q, Liu Y, Fan L, Wang F, et al. Exosomes from Melatonin Treated Hepatocellularcarcinoma Cells Alter the Immunosupression Status through STAT3 Pathway in Macrophages. Int J Biol Sci. 2017 May 16;13(6):723–734.

64. Gabrusiewicz K, Li X, Wei J, Hashimoto Y, Marisetty AL, Ott M, et al. Glioblastoma stem cell-derived exosomes induce M2 macrophages and PD-L1 expression on human monocytes. Oncoimmunology. 2018 Jan 16;7(4):e1412909.

65. Schwingshackl P, Obermoser G, Nguyen VA, Fritsch P, Sepp N, Romani N. Distribution and maturation of skin dendritic cell subsets in two forms of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome. Acta Derm Venereol. 2012 May;92(3):269–75.

66. Schlapbach C, Ochsenbein A, Kaelin U, Hassan AS, Hunger RE, Yawalkar N. High numbers of DC-SIGN+ dendritic cells in lesional skin of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010 Jun;62(6):995–1004.

67. Pileri A, Agostinelli C, Sessa M, Quaglino P, Santucci M, Tomasini C, et al. Langerhans, plasmacytoid dendritic and myeloid-derived suppressor cell levels in mycosis fungoides vary according to the stage of the disease. Virchows Arch. 2017 May;470(5):575–582.

68. Lüftl M, Feng A, Licha E, Schuler G. Dendritic cells and apoptosis in mycosis fungoides. Br J Dermatol. 2002 Dec;147(6):1171–9.

69. Berger CL, Tigelaar R, Cohen J, Mariwalla K, Trinh J, Wang N, et al. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: malignant proliferation of T-regulatory cells. Blood. 2005 Feb 15;105(4):1640–7.

70. Krejsgaard T, Lindahl LM, Mongan NP, Wasik MA, Litvinov IV, Iversen L, et al. Malignant inflammation in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma-a hostile takeover. Semin Immunopathol. 2017 Apr;39(3):269–82.

71. Wilcox RA, Wada DA, Ziesmer SC, Elsawa SF, Comfere NI, Dietz AB, et al. Monocytes promote tumor cell survival in T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders and are impaired in their ability to differentiate into mature dendritic cells. Blood. 2009 Oct 1;114(14):2936–44.

72. Kawana Y, Suga H, Kamijo H, Miyagaki T, Sugaya M, Sato S. Roles of OX40 and OX40 Ligand in Mycosis Fungoides and Sézary Syndrome. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Nov 22;22(22):12576.

73. Phillips D, Schürch CM, Khodadoust MS, Kim YH, Nolan GP, Jiang S. Highly Multiplexed Phenotyping of Immunoregulatory Proteins in the Tumor Microenvironment by CODEX Tissue Imaging. Front Immunol. 2021 May 19;12:687673.

74. Rindler K, Bauer WM, Jonak C, Wielscher M, Shaw LE, Rojahn TB, et al. Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Reveals Tissue Compartment-Specific Plasticity of Mycosis Fungoides Tumor Cells. Front Immunol. 2021 Apr 21;12:666935.

75. Pierce JM, Mehta A. Diagnostic, prognostic and therapeutic role of CD30 in lymphoma. Expert Rev Hematol. 2017 Jan;10(1):29-37.

76. van der Weyden CA, Pileri SA, Feldman AL, Whisstock J, Prince HM. Understanding CD30 biology and therapeutic targeting: a historical perspective providing insight into future directions. Blood Cancer J. 2017 Sep 8;7(9):e603.

77. Albrecht JD, Hein T, Şener ÖÇ, Müller-Decker K, Krammer P, Utikal JS, et al. Understanding the function of CD30 in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: implications for therapy and prognosis. Eur J Cancer. 2021 Oct 1;156:S11–2.

78. Su CC, Chiu HH, Chang CC, Chen JC, Hsu SM. CD30 is involved in inhibition of T-cell proliferation by Hodgkin's Reed-Sternberg cells. Cancer Res. 2004 Mar 15;64(6):2148–52.

79. Muta H, Boise LH, Fang L, Podack ER. CD30 signals integrate expression of cytotoxic effector molecules, lymphocyte trafficking signals, and signals for proliferation and apoptosis. J Immunol. 2000 Nov 1;165(9):5105–11.

80. Faber ML, Oldham RAA, Thakur A, Rademacher MJ, Kubicka E, Dlugi TA, et al. Novel anti-CD30/CD3 bispecific antibodies activate human T cells and mediate potent anti-tumor activity. Front Immunol. 2023 Aug 14;14:1225610.