Abstract

Purpose: To investigate the effects of prosthetic load on crestal bone loss within the maxillary and mandibular arches of a single individual.

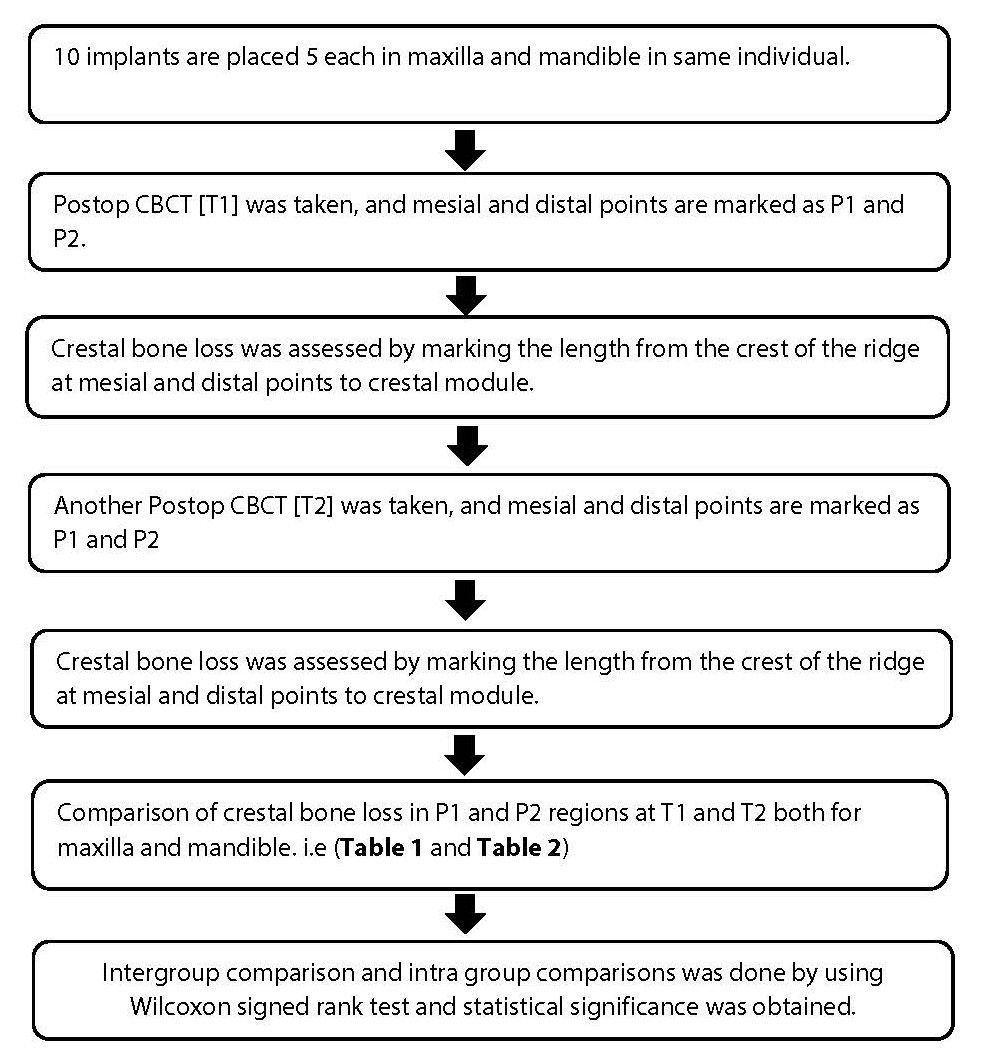

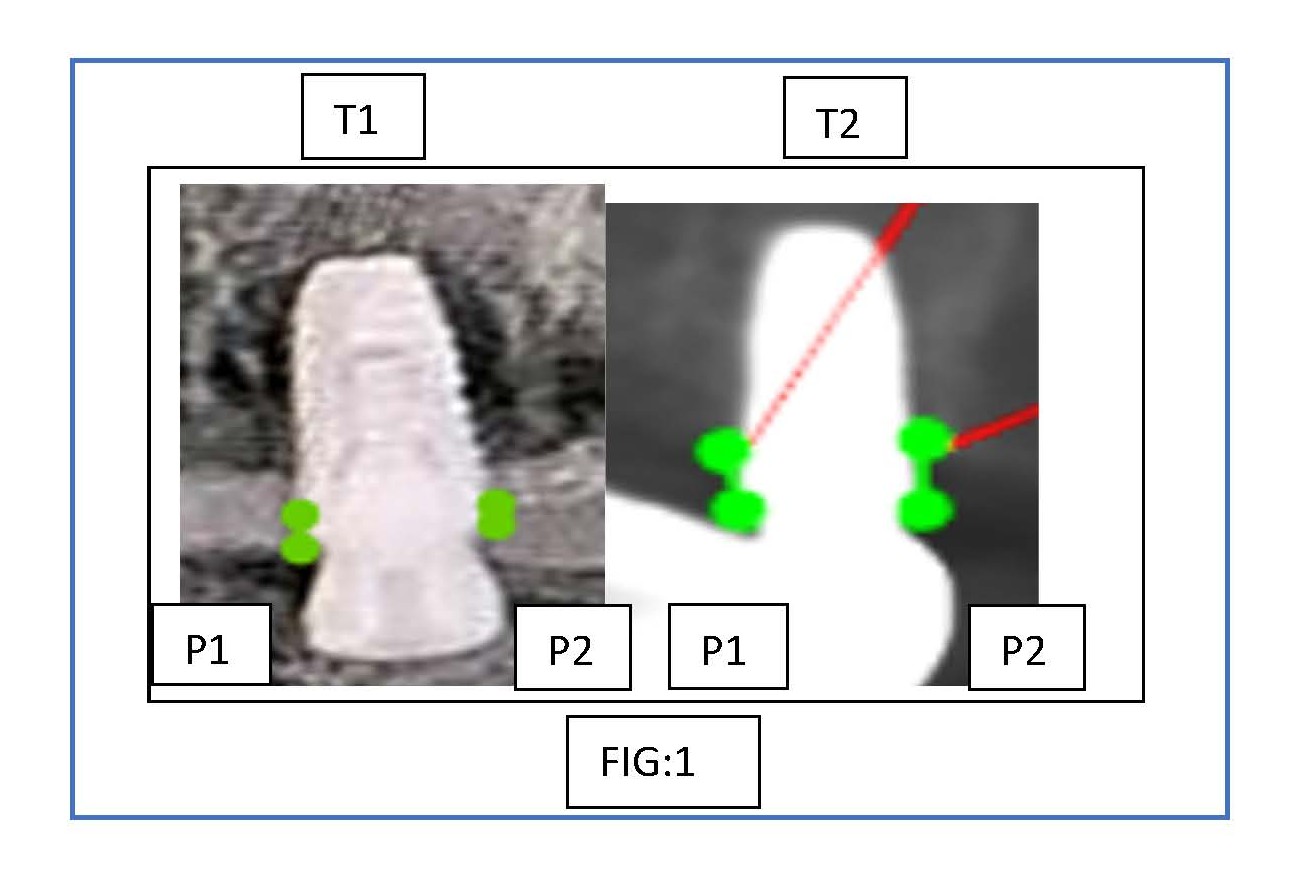

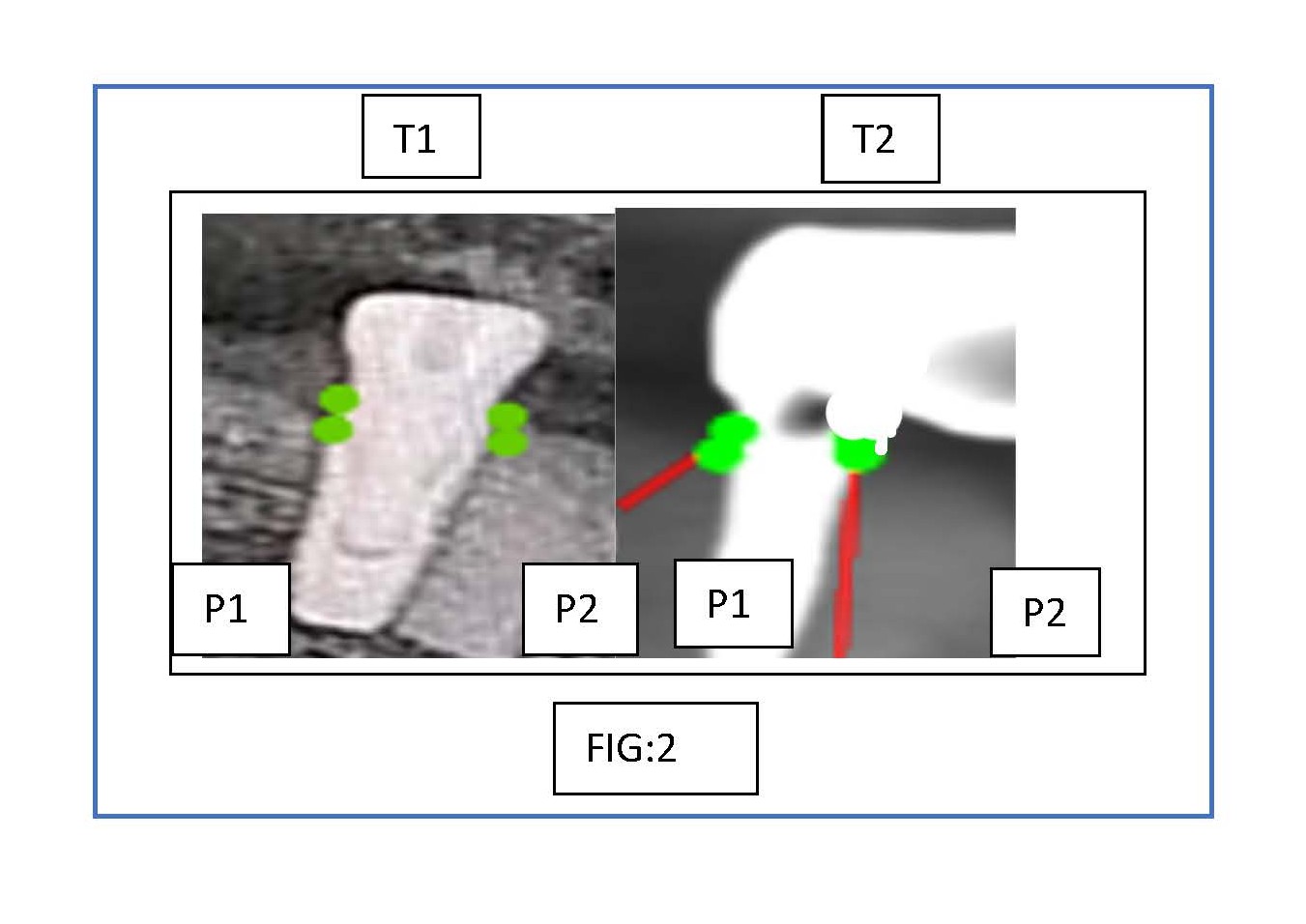

Materials and Methods: This study evaluated 10 implants from a single patient, 5 each from the maxillary and mandibular arches, with a follow-up of 12 months. Implants were assessed hinged to the load that is applied by the prosthesis mesial and distal points P1 and P2. Crestal bone loss was quantified by measuring bone level changes using cone beam computerized tomography (CBCT). Time T1 was defined as 3 months after implant placement, and T2 as the term after 12 months of implant positioning, follow-up visit. Group comparisons will be made using the Wilcoxon signed rank test, with significance set at p<0.05.

Result: A statistical significant difference was present and the mean crestal bone loss after prosthetic load is higher than preload; higher in maxillary arch when compared to that of mandibular arch in same individual.

Conclusion: In this study, crestal bone loss was higher in maxillary arch after prosthetic load rather than mandibular arch and preload.

Keywords

Crestal bone loss, Preload, Postload, Maxillary arch, Mandibular arch

Introduction

The amount and quality of peri-implant bone have a significant impact on osseointegration and the shape/contour of the soft tissue. Maintaining the peri-implant marginal bone is one of the most crucial and delicate requirements for treatment success [1]. Since almost all implants used today are of the osseointegrated kind, which was identified in 1960, the amount and quality of peri-implant bone have an impact on implant osseointegration [2]. The evaluation of peri-implant marginal bone is a crucial component in assessing the effectiveness of dental implants since bone stability is the key to implant success [3]. It is well known that the cortical bone has the lowest resistance to shear stress, which is greatly exacerbated by bending strain. Preoperative planning for dental implant placement is typically predicated on the availability of adequate bone height, which is impossible to confirm due to transverse limitations. Because it cannot produce cross-sectional images of the alveolar ridge, the commonly employed traditional panoramic radiography is the primary obstacle to measuring the dimensions of the alveolar bone both before and after implantation [4]. Traditional panoramic radiography is the most popular approach among the various methods found in the literature for peri-implant marginal bone evaluation [5]. The alveolar bone height surrounding the implant can be assessed by panoramic radiography. Its primary drawback is that it cannot produce cross-sectional pictures of the alveolar ridge. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to use cone beam computerized tomography (CBCT) analysis to evaluate and assess the crestal bone level at mesial and distal areas after 3 months [T1] of implant placement and after 12 months [T2] of implant placement.

Methodology

The methodology described below was employed in this study.

Figure 1. Comparison of crestal bone loss before and after prosthetic load in maxilla.

Figure 2. Comparison of crestal bone loss before and after prosthetic load in mandible.

|

|

|

T1 |

T2 |

||

|

MAXILLA |

|

P1 |

P2 |

P1 |

P2 |

|

1 |

1.0 mm |

1.3 mm |

1.5 mm |

1.7 mm |

|

|

2 |

0.9 mm |

1.2 mm |

1.0 mm |

1.3 mm |

|

|

3 |

0.8 mm |

0.9 mm |

1.8 mm |

1.9 mm |

|

|

4 |

0.9 mm |

1.1 mm |

1.0 mm |

1.2 mm |

|

|

5 (Figure 1) |

1.2 mm |

1.4 mm |

1.8 mm |

2.0 mm |

|

|

|

|

T1 |

T2 |

||

|

MANDIBLE |

|

P1 |

P2 |

P1 |

P2 |

|

1 |

0.6 mm |

0.8 mm |

1.0 mm |

1.5 mm |

|

|

2 |

0.5 mm |

0.4 mm |

0.9 mm |

1.1 mm |

|

|

3 |

1.0 mm |

1.2 mm |

1.0 mm |

1.2 mm |

|

|

4 |

1.5 mm |

1.6 mm |

1.0 mm |

1.4 mm |

|

|

5 (Figure 2) |

0.2 mm |

0.5 mm |

0.6 mm |

1.0 mm |

|

Results

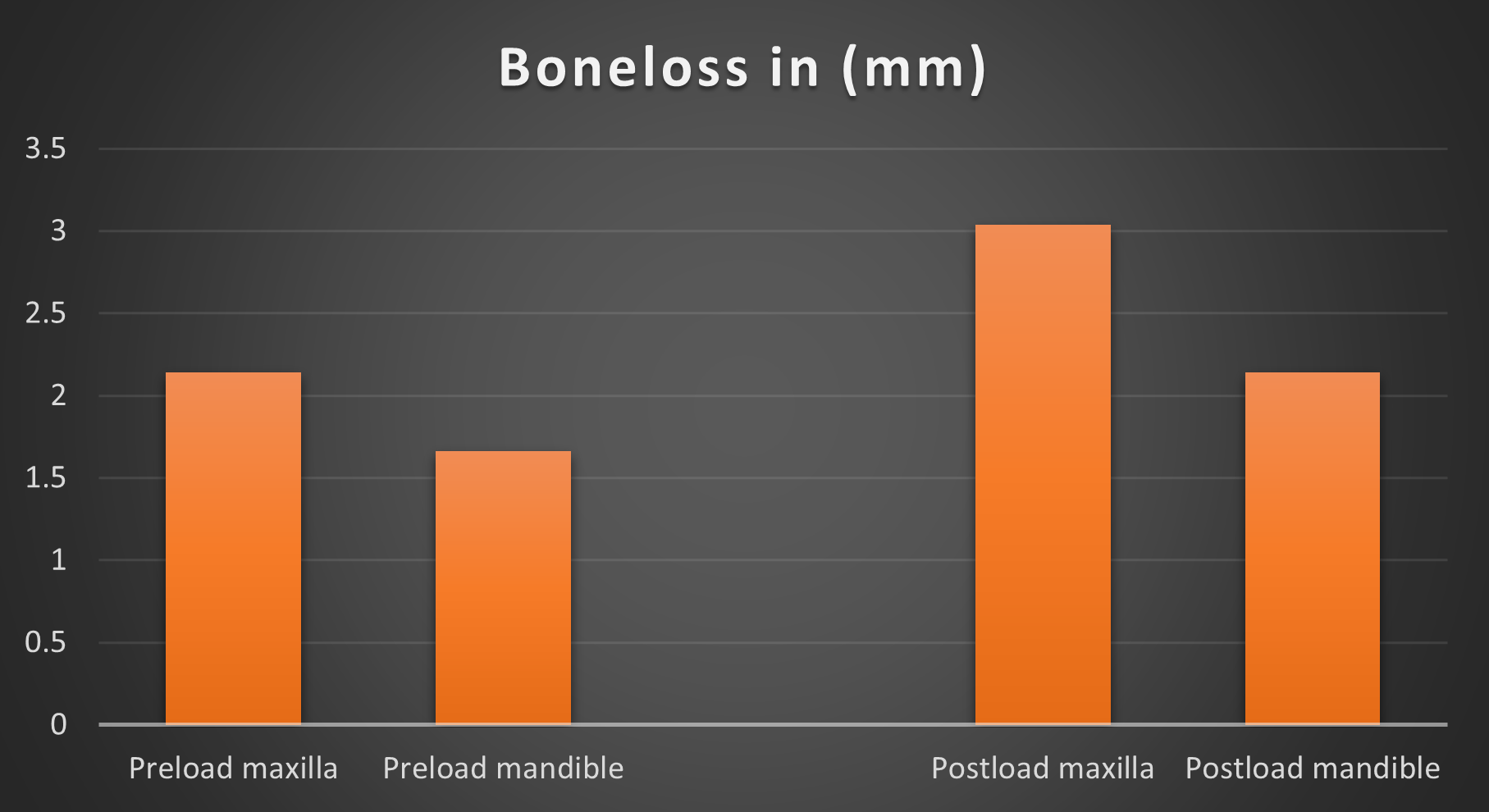

This study included 10 endo-osseous implants from single patient, out of which 5 are of maxilla and 5 are of mandible which were evaluated for bone loss in the mesial and distal regions prior to and following prosthesis loading (Table 3 and Figure 3).

The total bone loss in maxilla and mandible was also compared which were statistically significant with a mean bone loss of around 5.18 in maxilla and 3.80 in mandible (Table 4).

|

|

Descriptive Statistics |

Test Statistics |

||||

|

Sno |

Parameters |

Range |

Mean |

Std. Deviation |

Z-Value |

Asymp. Sig. (2-tailed) |

|

1 |

Preload Mesial |

1.50–.20 |

.8600 |

.11566 |

-2.630 |

.009* |

|

2 |

Preload Distal |

1.60–.40 |

1.0400 |

.12220 |

||

|

3 |

Postload Mesial |

1.80–.60 |

1.1600 |

.12667 |

-2.842 |

.004* |

|

4 |

Postload Distal |

2.0–1.00 |

1.4300 |

.10755 |

||

|

5 |

Preload total |

3.10–0.70 |

1.9000 |

.23476 |

-2.312 |

.021 |

|

6 |

Postload total |

3.80–1.60 |

2.5900 |

.23164

|

||

|

|

Descriptive Statistics |

Test Statistics |

|||

|

Parameters |

Mean |

Standard deviation |

Standard error of mean |

Z- value |

Asymp. Sig. (2-tailed) |

|

Maxilla |

5.18 |

.895 |

.40050 |

-1.576 |

.151 |

|

Mandible |

3.80 |

1.25 |

.56214 |

||

Figure 3. Bone loss in maxilla and mandible at preload and postload.

Discussion

In addition to indicating diminished oral function and alveolar bone loss, complete or partial edentulism that is not properly compensated by dentures or tooth-supported permanent prostheses which are frequently associated with a decline in self-esteem. A strong, close-knit, and long-lasting bond between the implant and the essential host bone which shapes in response to the masticatory load can be established by carefully positioning implants [4].

Both preserving marginal bone height and continuing osseointegration are necessary for the anchoring function. A mean of 1.2 mm of bone was lost, mostly during the healing and remodeling phase, which spanned from fixture installation to the end of the year following implant loading. Alberktsson et al. reported that a maximum bone loss of 0.2 mm per year, including the first year was permitted, this was also taken into consideration as a success criterion [6].

In general, CBCT is used for better study of accessible bone height, width, and density without considering superimposition, little distortion, high resolution, and small amounts of radiation than regular radiography. The bone loss is often all around so it is important to determine the degree of bone loss on mesial and distal sides which offers useful details about the quantity of loss of bone around dental implants [2].

Smith et al. suggested that one of the criteria for implant success was that less than 0.2 mm of alveolar bone loss occurred per year after the first year [7]. Adell et al. indicated that alveolar bone loss during the first year after abutment connection averaging 1.2 mm, and annual bone loss thereafter remained at approx. 0.1 mm for both the maxilla and the mandible [1]. According to Bryant et al., peri-implant bone loss is similar in elderly individuals and young adults. This shows that most authors agreed that patient age does not seem to be an important factor in peri-implant bone loss [8].

Within the first year following implant placement, there was an average bone loss of 1-1.5 mm which was almost similar to that of our study [9].

According to Johansson and Ekfeldt, the average bone loss during the first year was 0.4 mm. After the first year, Jang et al. discovered a 0.7 mm decrease in bone. The ranges for distal crestal resorption and mesial crestal resorption were 0.3 mm to 1.3 mm and 0.4 mm to 1.2 mm, respectively [10]. Within a year, Hürzeler et al. discovered a 0.40 mm (± 0.12 mm) decrease in bone [11].

Stress can be transferred to the bone implant interface by occlusal load provided through the implant prosthesis and its components. The amount of stress exerted via the implant prosthesis is directly correlated with the degree of bone strain at the bone implant contact. When occlusal forces above the physiological limitations of bone, the bone may experience enough strain to induce bone resorption [8].

Since Karolyi asserted a link between occlusal damage and bone loss surrounding natural teeth in 1901, the relationship has been contested. At stage 2 implant surgery, the bone is weaker and less thick than it is a year after prosthetic loading [9]. According to Ghahroudi et al. [12] there were no appreciable variations between the upper and lower implants in terms of the largest amount of bone loss that occurred in the distal and mesial sides of the mandibular and maxillary implants which was contrary to our study where we have found greater amount of bone loss is in maxilla rather than mandible which is similar to the findings of Peñarrocha et al. [13].

Lamichhane et al. [14] in his study concluded that there is more bone loss in distal aspect at preload rather than on the postload which was contrary to our study in which we have seen greater loss of crestal bone in distal aspects at postload.

Implant success varies with various factors like sex, age, systemic conditions, habits etc., thus we have done a study on same individual in order to reduce the bias, and evaluated for the crestal bone loss at mesial and distal points on implants in maxillary and mandibular regions at preload and postload and found out that there is a greater bone loss in distal point of maxilla at postload.

Conclusion

Long-term implant success depends critically on the integrity of the soft and hard tissues around the implant. The surgical skills of an oral implantologist and the patients' maintenance of oral hygiene are essential to the success of an implant. According to the study's limitations, the maxilla showed a greater loss of crestal bone at postload than the mandible did during preload.

References

2. Yi JM, Lee JK, Um HS, Chang BS, Lee MK. Marginal bony changes in relation to different vertical positions of dental implants. J Periodontal Implant Sci. 2010 Oct;40(5):244–8.

3. Trivedi A, Trivedi S, Narang H, Sarkar P, Sehdev B, Pendyala G, et al. Evaluation of Pre- and Post-loading Peri-implant Crestal Bone Levels Using Cone-beam Computed Tomography: An In Vivo Study. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2022 Jan 1;23(1):79–82.

4. DelBalso AM, Greiner FG, Licata M. Role of diagnostic imaging in evaluation of the dental implant patient. Radiographics. 1994 Jul;14(4):699–719.

5. Mayordomo BR, Martínez GR, Alfaro HF. Volumetric CBCT analysis of the palatine process of the anterior maxilla: a potential source for bone grafts. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2013;42(3):406–10.

6. Albrektsson T, Zarb G, Worthington P, Eriksson AR. The long-term efficacy of currently used dental implants: a review and proposed criteria of success. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 1986 Summer;1(1):11–25.

7. Smith DE, Zarb GA. Criteria for success of osseointegrated endosseous implants. J Prosthet Dent. 1989;62:567–72.

8. Bryant SR, Zarb GA. Crestal bone loss proximal to oral implants in older and younger adults. J Prosthet Dent. 2003 Jun;89(6):589–97.

9. Misch CE, Suzuki JB, Misch-Dietsh FM, Bidez MW. A positive correlation between occlusal trauma and peri-implant bone loss: literature support. Implant Dent. 2005 Jun;14(2):108-16.

10. Johansson LA, Ekfeldt A. Implant-supported fixed partial prostheses: A retrospective study. Int J Prosthodont. 2003;16:172–6.

11. Hürzeler M, Fickl S, Zuhr O, Wachtel HC. Peri‐implant bone level around implants with platform‐switched abutments: Preliminary data from a prospective study. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery: Official Journal of the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. 2007;65(7, Suppl 1):33–9.

12. Rasouli Ghahroudi A, Talaeepour A, Mesgarzadeh A, Rokn A, Khorsand A, Mesgarzadeh N, et al. Radiographic Vertical Bone Loss Evaluation around Dental Implants Following One Year of Functional Loading. J Dent (Tehran). 2010 Spring;7(2):89-97.

13. Peñarrocha M, Palomar M, Sanchis JM, Guarinos J, Balaguer J. Radiologic study of marginal bone loss around 108 dental implants and its relationship to smoking, implant location, and morphology. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2004 Nov-Dec;19(6):861–7.

14. Lamichhane S, Humagain M, Bhusal S, Rijal AH, Rupakhety P. Radiographic Evaluation of Crestal Bone Loss in Pre-loading and Post-loading States of Endosteal Implants in Maxilla and Mandible- A prospective study. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ). 2023 Oct.-Dec.;21(84):394–98.