Abstract

Mycobacterial inorganic pyrophosphatase (Mt-PPa) plays an essential role in Mycobacterium tuberculosis survival both in vitro and in vivo. This enzyme family hydrolyzes inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi) to release inorganic phosphate (Pi), thereby preventing pyrophosphate toxicity. The M. tuberculosis gene Rv3628 encodes a type I inorganic pyrophosphatase that exhibits metal-ion-dependent catalytic activity. In addition to its canonical pyrophosphatase function, Rv3628 also shows the ability to bind nucleotide triphosphates (GTP/ATP). The interaction between GTP and Rv3628, evaluated using isothermal titration calorimetry, revealed mild yet meaningful GTP-binding activity. Because GTP functions as a secondary messenger involved in numerous mycobacterial metabolic pathways, this interaction may represent an important component of cellular signaling cascades.

This study adopts a trilateral strategy integrating computational analysis, mutational profiling, and virtual screening to identify potential druggable features of Mt-PPa. Computational analyses indicated extensive interactions between Mt-PPa and genes associated with GTP- and ATP-dependent pathways. Epitope mapping further identified multiple amino acid regions within PPa that could act as immunologically relevant epitopes. Additionally, Mt-PPa was found to be sensitive to phosphorylation, with several Ser/Thr/Tyr residues serving as putative kinase targets.

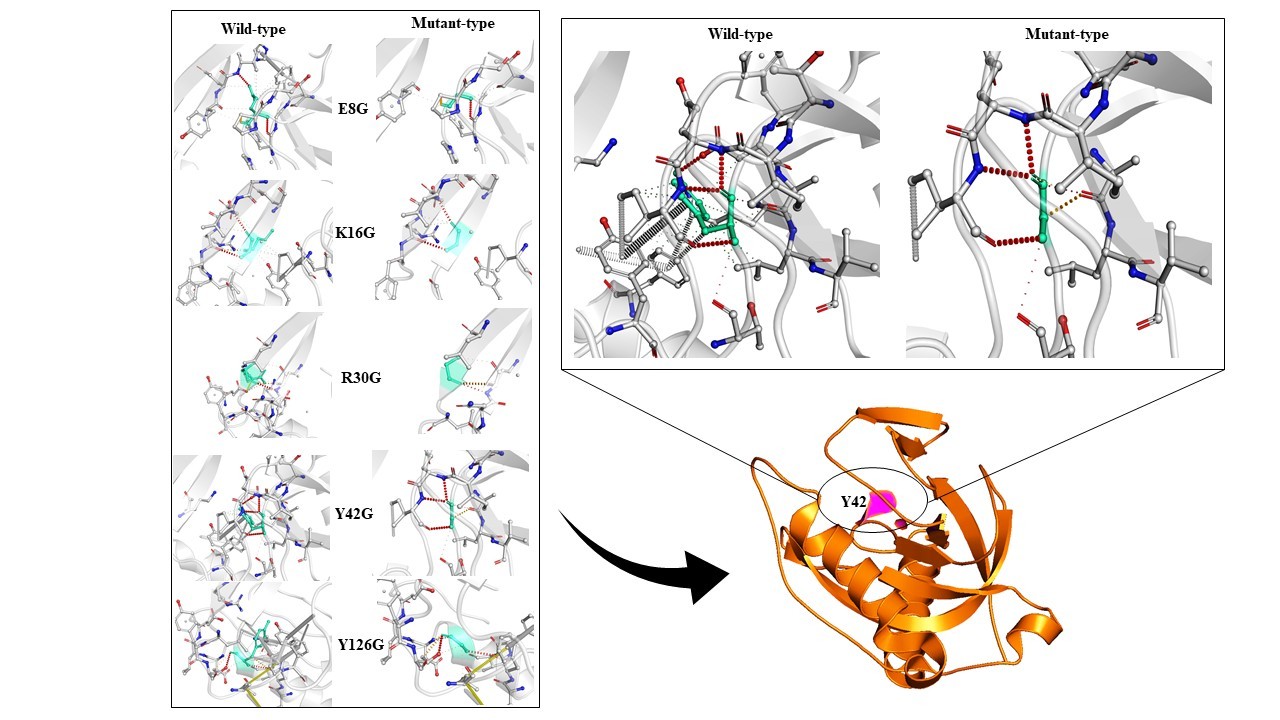

Mutational analysis identified W102G, V150G, F44G, I119G, L93F, F3G, F122G, I108G, L32G, M82G, Y17G, L59G, V5G, V26G, I7G, W140D, W140G, W140A, F80G, W140S, L49G, L56G, I9G, V60G, V19G, V92G, L28G, L61G, Y126E, and F123G as the top 30 destabilizing or functionally significant mutations. Among active-site residues, Y126G, Y42G, R30G, E8G, and K16G emerged as the most impactful mutational hits. Enzyme activity was also highly sensitive to temperature and pH, and mutations at His21 and His86 were found to shift the optimal pH range.

Virtual screening of 700 natural compounds from the Herbal Ingredient Targets (HITs) subset of the ZINC database identified ZINC000003979028, ZINC000003870413, ZINC000003870412, ZINC000150338758, ZINC0000070450948, ZINC000150338754, ZINC000095098891, ZINC000000119985, and ZINC000005085286 as top predicted binders to Mt-PPa. Additionally, the known GTPase inhibitors Mac0182344 and NAV-2729 were identified as promising molecules capable of targeting and inhibiting Mt-PPa activity.

Keywords

Mycobacterium tuberculosis, PPa, GTPase inhibitor, GTP, ITC

Abbreviations

TB: Tuberculosis; Mtb: Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv; MDR-TB: Multidrug-Resistant TB; GTPases: Guanosine triphosphatases; G-proteins: GTP-binding proteins; PDB: Protein Data Bank; RBC: Real Biotech Corporation; LB agar: Luria Bertani agar; LB broth: Luria Bertani broth; IPTG: Isopropyl β thiogalactoside; EDTA: Ethylene Diamine Tetra Acetate; PMSF: Phenylmethylsulphonyl Fluoride; SDS PAGE: Sodium Dodecyl Sulphate Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis; GEF: Guanine Nucleotide Exchange Factors; GAP: GTPases Activating Proteins; GDP: Guanosine Diphosphate; PCR: Polymerase Chain Reaction; ITC: Isothermal Calorimetry; UDP: Uridine Diphosphate; CDP: Cytidine Diphosphate; ADP: Adenosine Diphosphate; ATP: Adenosine Triphosphate; CTP: Cytidine Triphosphate; PPase: Pyrophosphatase; Mt-PPa: Mycobacterial Pyrophosphatase; NMA: Normal Mode Analysis; HITs: Herbal ingredients targets

Introduction

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) is a pathogenic bacterium that depends on the coordinated expression of several stress-responsive genes to survive hostile conditions imposed by the host during infection. This coordinated gene regulation enables the bacilli to persist in a latent phase for extended periods without exhibiting overt disease symptoms [1]. To establish a favorable survival niche within the host, Mtb employs diverse molecular strategies involving differential expression of genes associated with metal acquisition, DNA repair, pH homeostasis, detoxification, and thermo-tolerance, among others [2,3].

Inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi) is a catabolic byproduct generated during multiple essential cellular processes, including the synthesis of macromolecules (DNA, RNA, proteins) and various signaling pathways [4]. The hydrolysis of PPi into inorganic phosphate (Pi) is crucial for cell viability because the accumulation of PPi inhibits key biosynthetic pathways. This hydrolysis reaction is mediated by inorganic pyrophosphatases (PPases), which degrade PPi with a free energy change of ΔG = –5.63 ± 0.02 kcal [5,6]. Beyond hydrolysis, PPases have also been reported to catalyze the reverse reaction-forming PPi from Pi under specific conditions [7,8].

PPases are evolutionarily conserved and ubiquitously distributed across species. They are essential in Escherichia coli, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and Mtb [9]. These enzymes are classified into four families:

- Class I, II, and III PPases-predominantly cytoplasmic proteins

- Class IV PPases-integral membrane proteins involved in H+/Na+ transport [10]

Classes I and II are widely present in archaea, bacteria, and eukaryotes, whereas class III PPases have been identified in a smaller subset of bacteria and remain less explored [11,12]. Structurally, eubacterial PPases typically form homo hexamers with subunits of 19–22 kDa, while eukaryotic PPases exist as homodimers comprising 32–34 kDa subunits and possess a longer N-terminal extension [13]. Class I PPases across prokaryotes and eukaryotes share a conserved catalytic site containing 13 highly conserved residues, and Mg2+ is indispensable for their enzymatic function.

In Mtb, the class I PPase (Mt-PPa) is essential for bacterial survival and is considered a promising target for anti-tuberculosis drug development. Biochemical and structural insights into PPases from E. coli and S. cerevisiae have been extensively documented, and crystallographic data for Mt-PPa are available (PDB ID: 1WCF) [14,15]. Mycobacterial PPases differ from other bacterial PPases in that they contain two histidine residues in the active site, and their expression remains constitutive, independent of environmental conditions during in vitro growth. These histidines (His21 and His86) are associated with lowering intracellular pH and have been shown to participate in ATP and PNP hydrolysis using Mg2+ and Mn2+ as cofactors [14,16].

Multiple studies have reported that mutations within catalytic residues can significantly impair protein structural integrity and enzymatic function. Since Mt-PPase activity is strictly dependent on active-site architecture and metal coordination, mutations at these critical residues can disrupt intermolecular interactions, hinder catalysis, and ultimately compromise bacterial viability. A previous study identified 12 key active-site residues in Mt-PPa, including D84, D89, K127, K133, R30, K16, Y42, E8, D57, H86, H21, and P55, although their contributions may vary depending on the coordinating metal ion [17]. The present work examines how specific site-directed mutations influence Mt-PPa structural stability and catalytic function.

Protein stability and structural integrity are fundamental to proper cellular function, and any perturbation can have profound effects on the organism’s genotype, phenotype, and overall metabolism. The second major component of this study explores how different small-molecule compounds affect Mt-PPa structure and enzymatic activity. Molecular docking analyses were conducted with three groups of compounds: GTPase inhibitors, Herbal Ingredient Targets (HITs) [18], and nucleoside triphosphates (NTPs). Docking with GTPase inhibitors aimed to identify potential molecules capable of interfering with Mt-PPa activity. Additionally, virtual screening of HITs from the Zinc database was performed to discover compounds with strong binding affinity toward Mt-PPa and minimal predicted toxicity in humans.

In this article provides an integrated perspective combining in vitro and in silico analyses to enhance our understanding of Mt-PPa biology, its functional dynamics, and its potential as a drug target in Mtb.

Material and Methods

In vitro experiments

Protein expression and purification: The Mt-PPa gene was amplified by PCR reaction and M. tuberculosis H37Rv genomic DNA was used as template. The primers for the reaction were:

Forward Primer: 5’<GAGGATCCGCGTGCAATTCGACGTGACCATCG>3’

Reverse Primer: 5’<GCTCGAGTCAGTGTGTACCGGCCTTGAAGCGC>3’

The forward primer carrying BamHI restriction site and reverse primer carrying XhoI site. The gene was amplified by PTC-200 Peltier thermal cycler using the following program: initial denaturation at 95°C for 4 minutes followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 1 minute, 63°C for 1 minute, and 72°C for 1.30 minutes with a final extension at 72°C for 7 minutes. Both Mt-PPa PCR product and pPRO-EX-HTc vector were restriction digested with BamHI and XhoI to form compatible sticky ends. The size of both DNA and plasmid fragments was confirmed by agarose gel electrophoresis, and the bands were purified from the agarose gel by Qiagen gel extraction kit as per the manufacturer’s protocol [19]. The sticky ends generated in vector and insert were then used for ligation which was performed overnight at 16°C. The ligation mixture was heat-inactivated at 65°C and transformed into chemically competent HIT DH5α cells. The colonies were screened, the plasmid was isolated, and the expression construct was verified by restriction digestion and colony PCR which showed a band of similar size. The plasmid was then transformed into a chemically competent BL-21 (DE3) strain for protein expression. Taq DNA polymerase used for PCR and T4 DNA Ligase used for cloning were purchased from New England BioLabs (NEB).

Transformants were inoculated in 5 ml LB broth with 100 µg/ml ampicillin and incubated in an incubator shaker for overnight shaking at 200 rpm, 37°C. The protein was induced by Isopropyl-β-thiogalactoside (IPTG), which was added to the culture when OD600 reached 0.6–0.7 in around 2–2.30 hours and culture was induced for the next 5–5.30 hours. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 20 minutes at 4°C. Pellets were resuspended in 12 ml sonication buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 1 mM PMSF). Cells were lysed by sonication at 4°C for 5 minutes with an on and off cycle of 30 seconds till the lysate was clear. The sonicated cells were then centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 30 minutes for the removal of cell debris. The collected supernatant was then mixed with Ni-NTA resin (Qiagen) for 3 hours and then washed by washing buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 6.0, 300 mM NaCl, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 10 mM imidazole). The protein was eluted in elution buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 0.2 M imidazole). Eluted fractions were then analyzed on 10% SDS PAGE for purity and quantified using Bradford assay [20].

Dynamic light scattering: Dynamic light scattering was used to visualize the oligomeric state of the protein. The experiment was performed at 25°C and the reaction was set up at pH 8.0. Protein concentration of 0.8 mg/ml was used for the experiment which was made in buffer containing 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 1 mM PMSF. 1-cm path length cuvette of 1 ml volume capacity was used. A total of 20 runs were averaged with an equilibration time of the 70s. Zetasizer software (Ver. 6.20) analysis program was used for analyzing the histogram and the diameter of Mt-PPa protein was determined [21].

Isothermal titration calorimetry: The interaction of PPa with GTP was confirmed by isothermal titration calorimetry which evaluates the thermodynamic parameters of the interaction. All calorimetric reactions were performed on Malvern PEAQ ITC (Microcal, INC; Northampton, MA). All protein, ligand and buffer samples were filtered through 0.22 µm filter and degassed thoroughly before the start of the experiment. The protein was diluted in a buffer containing 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl to make a final concentration of 5 µM (in the cell) in a volume of 300 µl, and GTP was also diluted in the same buffer to a concentration of 500 µM (in the syringe) in a volume of 70 µl. GTP was titrated into the protein with total of 13 injections with the first injection being 0.4 µl and subsequent injections of 3 µl each with a data interval of 180 seconds. The reaction was performed at 25°C. Heat burst curves were obtained and the area under the curve was calculated using the Malvern inbuilt analysis program [22,23].

In silico methods

Interaction pattern: The interaction between proteins is an essential phenomenon for the establishment of any biological pathway and thus these interactions are also important for cell survival. The STRING database server provides comprehensive information on protein–protein functional associations. It employs a scoring system that ranges from 0 to 1 to evaluate the confidence of each predicted interaction. The value near 1 represents strong interaction whereas the value near 0 denotes weak interactions among proteins. On a similar pattern of analysis, STITCH server was used to determine protein-compound interaction [24].

B cell and t cell epitope prediction: The antigen part of a B-cell epitope binds to the immunoglobulin or antibody. These B-cell epitopes can be found in any exposed solvent region of the antigen and can be of various chemical types. The majority of antigens, however, are proteins, which are the targets of epitope prediction algorithms. T-cells, on the other hand, have a unique receptor on their surface known as the T-cell receptor (TCR), which allows antigens to be recognized when they are displayed on the surface of antigen-presenting cells (APCs), attached to major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules [25]. Evaluation of B-cell and T-cell epitopes is fundamental for various immunological, clinical, and biological applications, including diagnostics, disease control, vaccine development, and antibody engineering. In this study, B-cell and T-cell epitopes were predicted using the BCpred and ABCpred servers. Furthermore, to identify peptides with binding affinity to Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) class I and II molecules, the HLApred server was employed [26,27].

Prediction of subcellular localization: The protein cell confinement was anticipated by LOC tree3 and TBpred server [28]. The explanation of protein subcellular localization is critical for a thorough understanding of functionality. The prediction of protein sub-cell localization is a significant advancement toward identifying protein work. The server includes the machine learning-based LocTree2 and homology-based prediction strategy [29]. Another tool TBpred which is the SVM based technique for subcellular localization forecasting strategy for mycobacterial protein is likewise utilized for foreseeing four localization areas for example cytoplasmic, secretory, inclusion body and transmembrane protein.

Ligand binding site prediction: Ligand binding to the specific binding site of a protein is a critical determinant of its structural integrity and functional activity. Numerous bioinformatics servers were utilized to predict the coupling site like 3DLigandSite, ProBis and FINDSITE etc. [30–32]. These tools are layout-based strategies and LIGSITE and VICE were utilized as mathematical techniques. Here we utilized COACH server that evaluates the site that binds to Mt-PPa. Sequence arrangement and 3D structure of target protein were used to produce ligand binding sites by utilizing two strategies TM-SITE and S-SITE. ProBis web server recognizes the capable ligand interaction to the ppa protein structure. The ligands sought in the similar binding site are transposed to the Mt-PPa by rotation and translation of their atoms. At that point, the basic binding amino acid residues between Mt-PPa and source protein from which ligands are rendered are recognized [33].

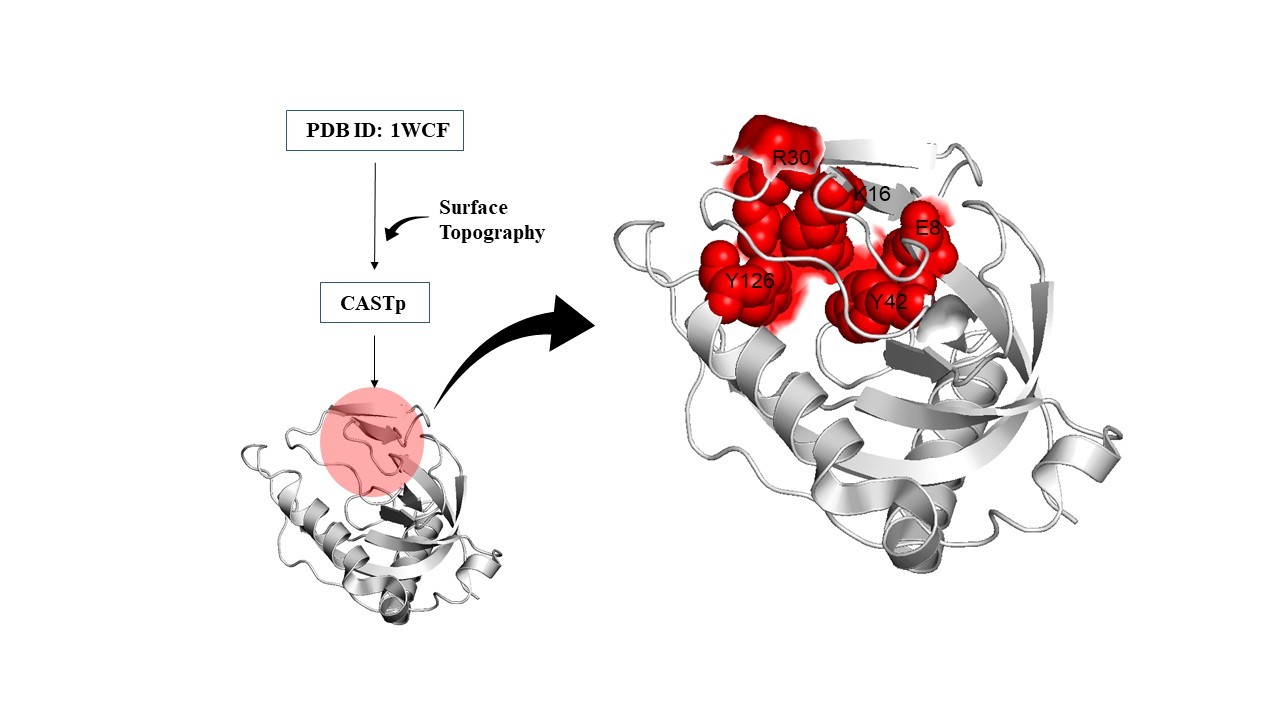

Active site analysis and residues selection: The protein sequence of Mt-PPa was analyzed by Mycobrowser server that provides the genomic and proteomic sequence of all mycobacterial species. Mycobrowser is a convenient web server and provides all necessary information related to mycobacteria. It also includes data for mycobacterial structure, function, orthologs, and all information regarding drug development. The protein sequence was used for the determination of GTPase and pyrophosphatase active site motif by Computed Atlas of Surface Topography of proteins (CASTp) server which is a web-based tool for identifying, defining, and quantifying concave surface regions on three-dimensional protein structures [34].

Structure-based mutation analysis:

Duet: DUET web server analyzes the effect of missense mutations. It uses the joint methodological pattern of mCSM and SDM in an optimized indicator machine called Support Vector Machine. mCSM subjected on graph-based system and can identify the effect of single point mutation and evaluate protein-protein and protein-nucleic acid binding [35].

Site-directed mutator: Site-directed mutator is an in-silico tool to determine substitution mutation impact on overall protein stability. This tool serves as an input system for PDB-derived structure and gives output as Gibbs free energy (ΔΔG value) of stability change. ΔΔG values of stabilizing mutation ranges in ΔΔG >2.5 kcal/mol and destabilizing mutations ranges in ΔΔG <2.5 kcal/mol [36].

DynaMut: Proteins are an important and dynamic molecule that intrinsically associates with molecular signals. DynaMut server exemplifies the effect of mutations and depends upon protein static structure. This server evaluates two distinct but modest tactics to estimate and visualize the steadiness of protein by a variety of conformations and valuation of the role of mutations on dynamicity and stability of protein resulting in a change of vibrational entropy. It can evaluate protein dynamics by single point mutations and setting the cutoff value ΔΔG≥0 for stabilizing and ΔΔG < 0 for destabilization of the protein. DynaMut evaluates NMA over two assorted advances, Bio3D and ENCoM, that provide rapid and basic admittance to influential and insightful analysis of protein motions. Normal Mode Analysis (NMA) designs consonant movement to peddle a viable dynamic framework for mutation [36].

Virtual screening of GTPase inhibitor, NTPs and ZINC natural compounds against Mt-PPa: Molecular docking-based virtual screening of all compounds with PDB structure (1SXV) of mycobacterial PPa was performed to predict their binding affinity and detailed interactions. The docking was performed using InstaDock, a single click molecular docking tool that automizes the entire process of molecular docking-based virtual screening [37]. The binding affinities between the ligand and protein were calculated using the QuickVina-W [38] (Modified AutoDock Vina [36]) program which uses a hybrid scoring function (empirical + knowledge-based) in docking calculations and a blind search space for the ligand.

The pKi, the negative decimal logarithm of inhibition constant [39] was calculated from the ΔG parameter using the following formula:

ΔG = RT(Ln Kipred)

Kipred = e(ΔG/RT)

pKi = -log (Kipred)

where ΔG is the binding affinity (kcal mol-1), R (gas constant) is 1.98 cal*(mol*K)-1, T (room temperature) is 298.15 Kelvin, and Kipred is the predicted inhibitory constant.

Ligand efficiency (LE) is a commonly applied parameter for selecting favorable ligands by comparing the values of average binding energy per atom [37]. The following formula was applied to calculate LE:

LE = -ΔG/N

where LE is the ligand efficiency (kcal mol-1 non-H atom-1), ΔG is binding affinity (kcal mol-1) and N is the number of non-hydrogen atoms in the ligand.

Results

Purification of Mt-PPa protein

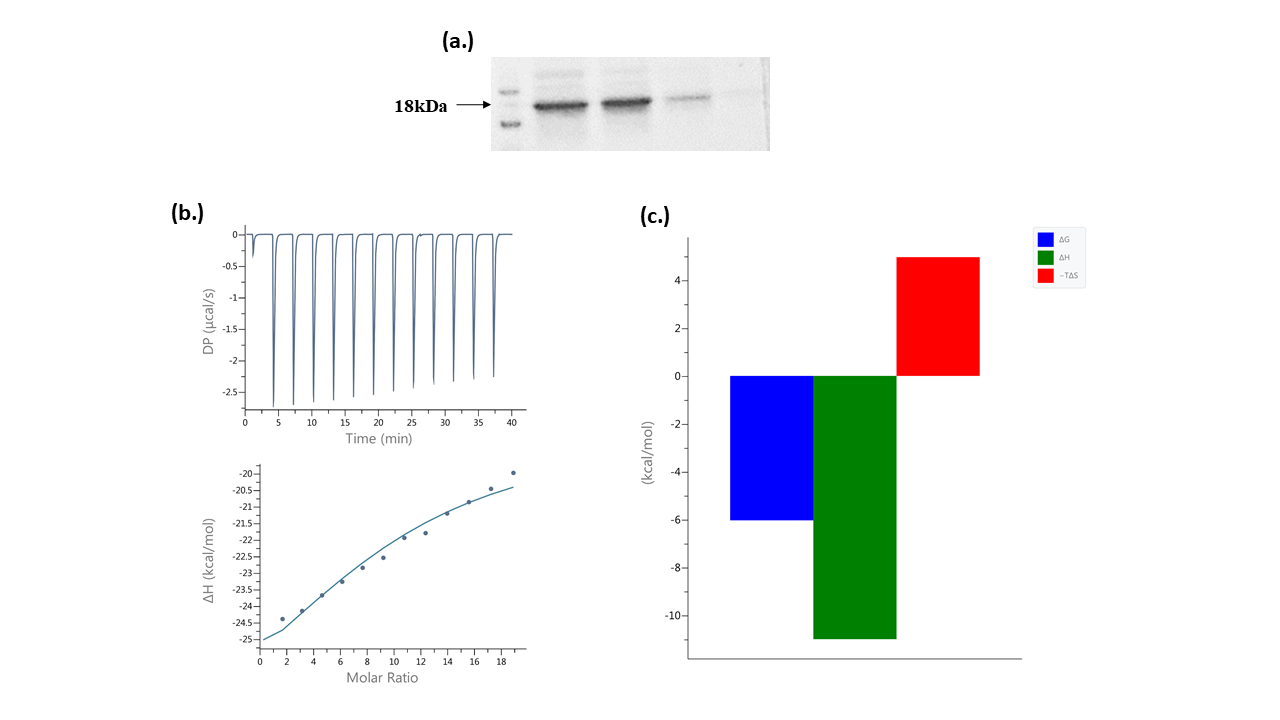

The Mt-PPa gene was cloned into pPRO-EX-HTc using BamHI and XhoI restriction site in forward and reverse primer respectively. Mt-PPa was over-expressed in the BL-21 (DE3) strain with an N terminal His-tag. The protein was induced by adding 1 mM IPTG after OD600 reached 0.7-0.8 and protein expression levels were confirmed using SDS-PAGE. The protein was purified to 80% purity, and the molecular mass of the purified protein was estimated as 18 kDa by SDS PAGE. Purified Mt-PPa+His was concentrated then quantified by Bradford assay (Figure 1a).

There was a moderate interaction between GTP and Mt-PPa

Isothermal calorimetry was used to determine the type of interaction and heat involved for optimum interaction between Mt-PPa and GTP. The data was analyzed by fitting the heat burst curve in one site binding model. The stoichiometry (N) and dissociation constant (Kd) of the interaction were 10 and 37.9±7 µM respectively (Figure 1b). The heat was released in the form of enthalpy change (ΔH) which is -11±1.2 kcal/mol. ΔG was -6.3 kcal/mol and TΔS was -4.96 kcal/mol (Figure 1c).

Figure 1. Protein purification and interaction analysis. (a.) Purified Mt-PPa protein fractions with molecular marker (b.) Isothermal calorimetry: Saturation curve of interaction between GTP and Mt-PPa (c.) Thermal graph: The thermal parameters showed spontaneous reaction with negative ΔG, ΔH, and positive TΔS.

Interaction analysis

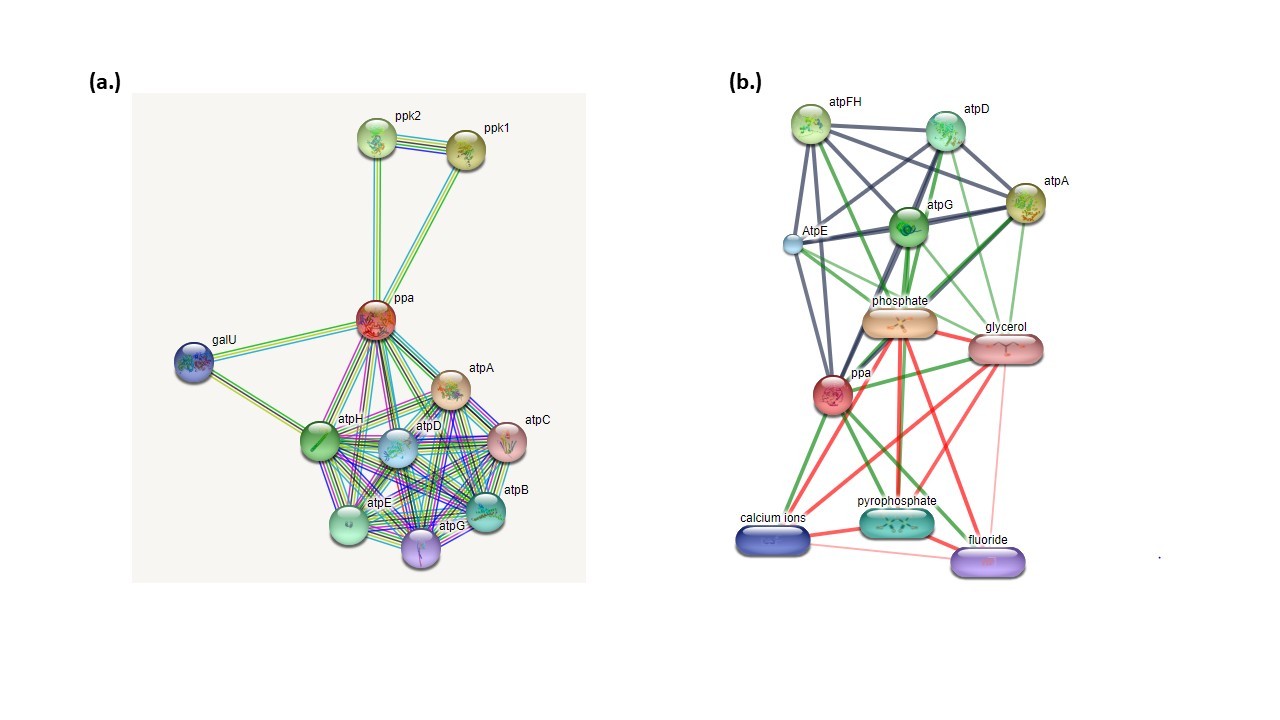

The STRING server was used to identify protein–protein interactions, while the STITCH server was employed to predict protein–chemical interactions. STRING showed the prominent interaction with ATP synthase family proteins (atpA, atpB, atpC, atpD, atpE, atpF, atpG and atpH), galU, Ppk1 and ppk2. The scores for all interactive partners were around 0.9 (Figure 2a). STITCH server showed the interaction with phosphate, pyrophosphate, fluoride, calcium ion, glycerol with scores as 0.991, 0.965, 0.954, 0.954, and 0.946 respectively. The scoring of all interactions indicated robust protein–protein as well as protein–compound associations (Figure 2b).

Figure 2. Interaction analysis: (a.) Protein-protein interaction: Protein-protein interaction was analyzed by STRING server that showed Mt-PPa interaction with ATP family protein and ppk1 and ppk2 with score greater than 0.9. (b.) Protein–compound interactions were analyzed using the STITCH database, which revealed strong binding with pyrophosphate, calcium, fluoride, and glycerol, with confidence scores ranging from 0.8 to 1.0.

Ligand-binding prediction

COACH server is a meta server-based approach that was used for the prediction of ligand binding site in the protein. COACH server works on two mechanisms known as TM-site and S- site that recognized ligand binding template from the BioLip database. The server found the top hit ligands that bind to the PPa were sulfate ion, phosphate ion, potassium ion, calcium ion and Manganese ion. The topmost confidence scores (C score) were 0.39 and 0.33 for sulfate and phosphate ion respectively. The consensus residues where sulfate ion binds are 16, 30, 84, 126, and 127 and the residues where phosphate ion binds are 16, 30, 42, 57, 84, 89, 91, 126, and 127. The TM site prediction has also cleared the binding of the protein with phosphate, sulfate and magnesium ions with a C score of 0.29, 0.28, and 0.26 respectively. The S site results also found the interaction of manganese, phosphate and sulfate ions with C score 0.33, 0.24 and 0.20 respectively. In the COFACTOR outcome, the TM score was 0.970, 0.969 and 0.968 for calcium, manganese and phosphate ions respectively.

Mutational analysis

The impact of point mutations on the activity of Mt-PPa was assessed by utilizing sequence-based changes. The mutations were done utilizing EASE-MM, PROVEAN, I-Mutant and DynaMut servers. It is now a well-established statement that point mutations are the significant aspect of certain diseases because of their extent to affect protein structure and function. Considering energy change in thermodynamics, a protein can stay stable which is in the folded state, or it is in the unfolded state that is also known as the unstable state of the protein. The distinction of energy between folded and unfolded states can be determined by Gibbs free energy ΔG=Gu−Gf, where Gu and Gf are the gibbs energy of unfolded and folded states separately. Another method used to measure a change in Gibbs free energy of mutated and wild type protein appeared by ΔΔG where ΔΔG =ΔGm–ΔGw (ΔGm= Gibbs free energy of mutated and ΔGw= Gibbs free energy of wild protein).

The EASE-MM predictive tool requires protein amino acid sequence information and predicts the effect of mutations at each residue by substitution of amino acids at a given position within the primary sequence. The server showed the top 30 mutations with the highest destability. W102G, V150G, F44G, I119G, L93F, F3G, F122G, I108G, L32G, M82G, Y17G, L59G, V5G, V26G, I7G, W140D, W140G, W140A, F80G, W140S, L49G, L56G, I9G, V60G, V19G, V92G, L28G, L61G, Y126E, and F123G were the top 30 hits by EASE-MM server by setting a cutoff ΔΔG value of -4.0 (Table 1). In addition to the above-mentioned mutational hits, mutations were also carried out on active site residues. As Mt-PPa is a pyrophosphatase and carried out its work based on active site configuration, therefore mutations on the active site residues must be checked. The active site was predicted by CASTp server and there are 5 residues that are present in the active site as Y126G, Y42G, R30G, E8G, and K16G (Table 2). These active sites are involved in the pyrophosphatase function of Mt-PPa. Mutations at all active site residues showed a destabilized effect with the highest destabilizing effect of Y126G.

All mutational hits resulted from EASE-MM server were also checked by PROVEAN server that proved a mutation as deleterious or non-deleterious. The PROVEAN resulted in the highest destabilized mutations of PPa i.e. W140D, W140A, W140S, W140G, Y17G, F122G, F123G, and Y126E (Table 1). Mutations on active site residues Y126G, Y42G, R30G, E8G, K16G were also showed a destabilized effect with the highest destability at Y126G (Table 2).

Similarly, all 30 mutational hits were also checked by I-MUTANT 3.0 server and the resulting outcome showed L28G, L32G, I7G, V26G, L93F, I119G, F122G, I108G, L59G, F80G, I9G, V19G (Table 1) as the highest destabilized mutations. Active site residue mutation showed destability at all point changes with the highest destability at K16G (Table 2).

|

S.No. |

Residue |

Ease MM |

Provean |

I Mutant 3.0 |

|

1 |

W102G |

-4.9260 |

-4.270/Deleterious |

-1.92 |

|

2 |

V150G |

-4.1111 |

-6.245/Deleterious |

-1.76 |

|

3 |

F44G |

-4.4003 |

-7.503/Deleterious |

-2.12 |

|

4 |

I119G |

-4.5212 |

-7.769/Deleterious |

-2.55 |

|

5 |

L93F |

-4.4532 |

-3.937/Deleterious |

-2.68 |

|

6 |

F3G |

-4.4500 |

-7.769/Deleterious |

-2.21 |

|

7 |

F122G |

-4.6320 |

-8.969/Deleterious |

-2.43 |

|

8 |

I108G |

-4.2590 |

-6.596/Deleterious |

-2.50 |

|

9 |

L32G |

-4.1747 |

-7.911/Deleterious |

-3.34 |

|

10 |

M82G |

-4.1845 |

-7.992/Deleterious |

-1.80 |

|

11 |

Y17G |

-4.3607 |

-9.889/Deleterious |

-2.28 |

|

12 |

L59G |

-4.5909 |

-7.579/Deleterious |

-2.54 |

|

13 |

V5G |

-4.1883 |

-6.260/Deleterious |

-2.17 |

|

14 |

V26G |

-4.0069 |

-6.759/Deleterious |

-2.80 |

|

15 |

I7G |

-4.7302 |

-7.507/Deleterious |

-2.81 |

|

16 |

W140D |

-4.0817 |

-14.786/Deleterious |

-1.43 |

|

17 |

W140G |

-4.8978 |

-12.954/Deleterious |

-1.69 |

|

18 |

W140A |

-4.0414 |

-13.953/Deleterious |

-1.20 |

|

19 |

F80G |

-4.730 |

-8.402/Deleterious |

-2.38 |

|

20 |

W140S |

-4.4166 |

-13.853/Deleterious |

-1.33 |

|

21 |

L49G |

-4.0531 |

-7.906/Deleterious |

-2.48 |

|

22 |

L56G |

-4.4514 |

-7.704/Deleterious |

-2.34 |

|

23 |

I9G |

-4.6410 |

-7.839/Deleterious |

-2.89 |

|

24 |

V60G |

-4.1519 |

-6.856/Deleterious |

-2.21 |

|

25 |

V19G |

-4.0048 |

-6.504/Deleterious |

-2.60 |

|

26 |

V92G |

-4.0486 |

-6.505/Deleterious |

-2.35 |

|

27 |

L28G |

-4.5469 |

-7.911/Deleterious |

-3.51 |

|

28 |

L61G |

-4.2705 |

-7.428/Deleterious |

-2.59 |

|

29 |

Y126E |

-4.7996 |

-8.991/Deleterious |

-0.85 |

|

30 |

F123G |

-4.4530 |

-8.969/Deleterious |

-2.48 |

|

|

EASE MM |

PROVEAN |

I mutant |

DynaMut |

|

E8G |

-2.3658 |

-6.922 |

-2.13 |

-1.004 |

|

K16G |

-1.6227 |

-6.922 |

-2.44 |

-1.700 |

|

R30G |

-3.1748 |

-6.922 |

-1.58 |

-0.877 |

|

Y42G |

-3.9978 |

-9.889 |

-1.10 |

-3.295 |

|

Y126G |

-4.7996 |

-9.990 |

-1.13 |

-2.079 |

Stress-based mutation analysis is an important aspect to analyze the stability and structural differences of protein at different conditions. It was done by changing the pH and temperature from the optimum range to see if protein would attain stability or destability in different conditions. Increasing temperature from 4°C to 60°C (Table 3) showed a decrease in destability and increasing pH from 3 to 13 (Table 4) also showed a decrease in stability till pH 7 and a slight increase in stability after pH 7 to 13.

|

Temp Mutation |

4°C |

16°C |

25°C |

37°C |

42°C |

60°C |

|

Y126G |

-2.28 |

-2.20 |

-2.13 |

-2.04 |

-1.97 |

-1.76 |

|

Y42G |

-2.60 |

-2.52 |

-2.44 |

-2.32 |

-2.26 |

-2.03 |

|

R30G |

-1.76 |

-1.66 |

-1.58 |

-1.46 |

-1.40 |

-1.19 |

|

E8G |

-1.33 |

-1.20 |

-1.10 |

-0.94 |

-0.88 |

-0.77 |

|

K16G |

-1.31 |

-1.21 |

-1.13 |

-1.02 |

-0.97 |

-0.89 |

|

pH Mutation |

3 |

5 |

7 |

10 |

13 |

|

Y126G |

-2.13 |

-2.14 |

-2.13 |

-2.06 |

-2.08 |

|

Y42G |

-2.46 |

-2.47 |

-2.44 |

-2.35 |

-2.20 |

|

R30G |

-1.51 |

-1.56 |

-1.58 |

-1.58 |

-1.53 |

|

E8G |

-1.05 |

-1.08 |

-1.10 |

-1.09 |

-1.05 |

|

K16G |

-1.11 |

-1.13 |

-1.13 |

-1.12 |

-1.07 |

Phosphorylation site prediction

Protein phosphorylation controls an enormous assortment of biological processes in every living cell. In pathogenic microorganisms, the investigation of serine, threonine, and tyrosine (Ser/Thr/Tyr) phosphorylation has revealed insight into the course of infectious diseases, from adherence over cells to microbial pathogenesis and replication etc. The NetPhos3.1 server predicts serine, threonine, or tyrosine phosphorylation positions in proteins utilizing outcomes of neural organizations. The phosphorylation point follows a task field depicting the anticipated class for every residue. If the residue is predicted NOT to be phosphorylated, either because the score is below the threshold or because the residue is not Ser/Thr/Tyr, that position is marked by a dot ('.'). Residues having a prediction score above the threshold were indicated by 'S', 'T' or 'Y', respectively (Table 5).

|

S. No. |

Residue |

Context |

Score |

Kinase |

|

1. |

Y2 |

MYCXXA |

0.400 |

INSR |

|

2. |

T8 |

ACTERIX |

0.586 |

unsp |

|

3. |

T14 |

RIXMTXXER |

0.734 |

Unsp |

|

4. |

T14 |

RIXMTXXER |

0.541 |

CKII |

|

5. |

T56 |

VDHETGRVR |

0.795 |

Unsp |

|

6. |

T56 |

VDHETGRVR |

0.705 |

PKC |

|

7. |

Y64 |

RLDRYLYTP |

0.618 |

unsp |

|

8. |

T73 |

MAYPTDYGF |

0.500 |

PKG |

|

9. |

Y75 |

YPTDYGFIE |

0.683 |

Unsp |

|

10. |

T81 |

FIEDTLGDD |

0.801 |

Unsp |

|

11. |

T81 |

FIEDTLGDD |

0.519 |

CKI |

|

12. |

Y159 |

FFVHYKDLE |

0.511 |

unsp |

|

13. |

S186 |

EVQRSVERF |

0.995 |

unsp |

|

14. |

S186 |

EVQRSVERF |

0.995 |

unsp |

|

15. |

T194 |

FKAGTH |

0.660 |

PKC |

The epitopic recognition

B cell epitope prediction was performed by the BCpred server which detects amino acid chain lengths of 7–10 amino acids that are predicted to participate in epitope-like functions. In BCpred, there were 4 epitopes found, of length 20 amino acids at different positions. The epitopes were AADWVDRAEAEAEVQRSVER at position 137 with a score of 0.996, EHGGDDKVLCVPAGDPRWDH at position 85 with a score of 0.99, DVTIEIPKGQRNKYEVDHET at position 4 with a score of 0.921, and TPMAYPTDTGFIEDTLGDDG at position 34 with a score of 0.891. Another tool known as ABCpred was also used for the same information. The predicted B cell epitopes are ranked according to their score obtained by a trained recurrent neural network.

A higher score of the peptide means a higher probability to be an epitope. The threshold value was set at 0.51 and epitope length of 16 amino acids. The top four epitopes were FRMVDEHGGDDKVLCV, GVLVAARPVGMFRMVD, DVTIEIPKGQRNKYEV and FFVHYKDLEPGKFVKA at position 80, 69, 4 and 122 and with score 0.93, 0.90, 0.88, and 0.88 respectively. HLA pred was used to determine T cell epitope in combination with MHC-II molecule. The top ten epitopic regions were DLEPGKFVK, FELDAIKHF, FRMVDEHGG, GKFVKAADW, IKHFFVHYK, LLPQPVFPG, LPQPVFPGV, LVAARPVGM, LVLLPQPVF and LVLLPQPVF. A list of top epitopes was given in (Table 6).

|

S. No. |

Sequence |

Start Position |

Score |

|

1 |

FRMVDEHGGDDKVLCV |

80 |

0.93 |

|

2 |

GVLVAARPVGMFRMVD |

69 |

0.90 |

|

3 |

DVTIEIPKGQRNKYEV |

4 |

0.88 |

|

3 |

FFVHYKDLEPGKFVKA |

122 |

0.88 |

|

4 |

LCVPAGDPRWDHVQDI |

93 |

0.86 |

|

4 |

GRVRLDRYLYTPMAYP |

24 |

0.86 |

|

4 |

NKYEVDHETGRVRLDR |

15 |

0.86 |

|

5 |

DHVQDIGDVPAFELDA |

103 |

o.84 |

|

6 |

YGFIEDTLGDDGDPLD |

42 |

0.83 |

|

7 |

YTPMAYPTDYGFIEDT |

33 |

0.80 |

|

8 |

AADWVDRAEAEAEVQR |

137 |

0.77 |

|

9 |

AFELDAIKHFFVHYKD |

113 |

0.76 |

|

10 |

LGDDGDPLDALVLLPQ |

49 |

0.72 |

|

11 |

LVLLPQPVFPGVLVAA |

59 |

0.71 |

|

12 |

EAEVQRSVERFKAGTH |

147 |

0.69 |

Screening of compounds against Mt-PPa (1wcf)

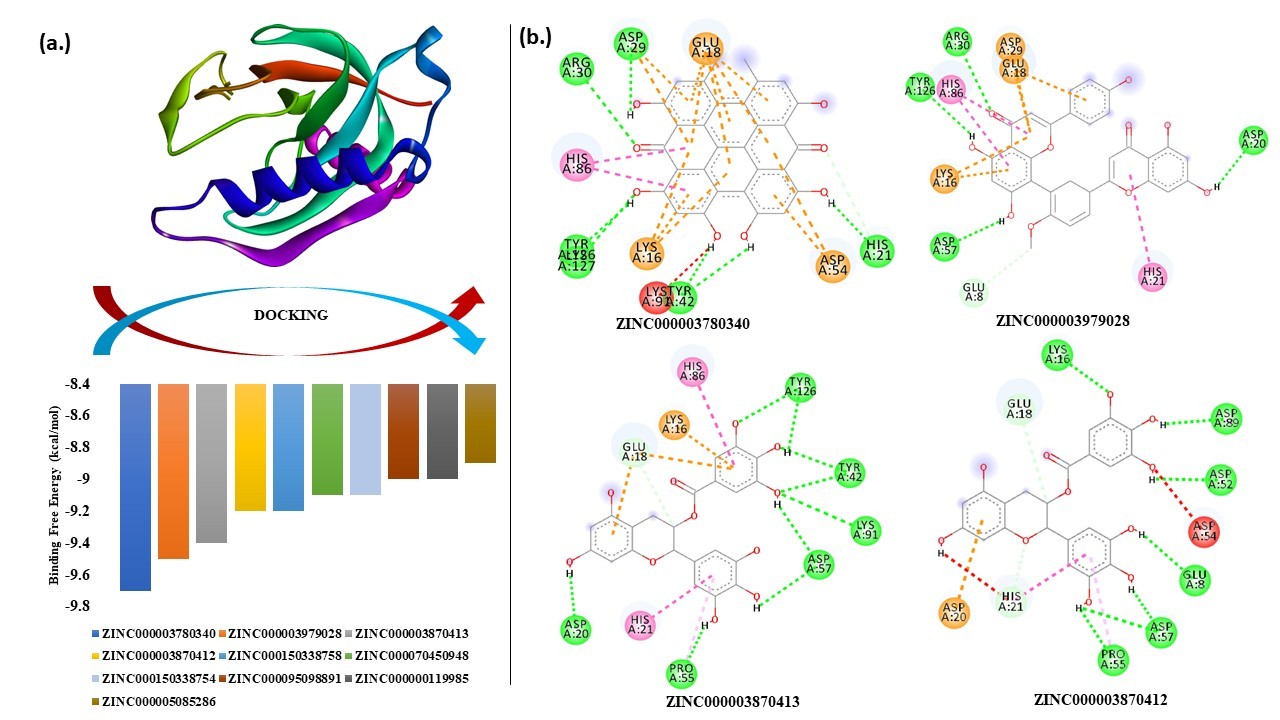

Screening of ZINC herbal compound database: Mt-PPa is an essential gene for in vitro and in vivo survival of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mt-PPa also provides advanced endurance mechanisms to the bacterium. Virtual screening was performed using docking to select the potent natural and synthetic inhibitors. We had used a subset of the Zinc database library known as herbal ingredient targets (HITs) to select the herbal ingredient compound. The screening was performed by targeting the residues of the active site and the results were generated. Among the 750 compounds from Zinc database of herbal ingredients, all compounds were successfully bound and Compound ZINC000003780340 showed the highest binding energy, which is followed by compound ZINC000003979028, ZINC000003870413, ZINC000003870412, ZINC000150338758, ZINC0000070450948, ZINC000150338754, ZINC000095098891, ZINC000000119985, ZINC000005085286 (Table 7).

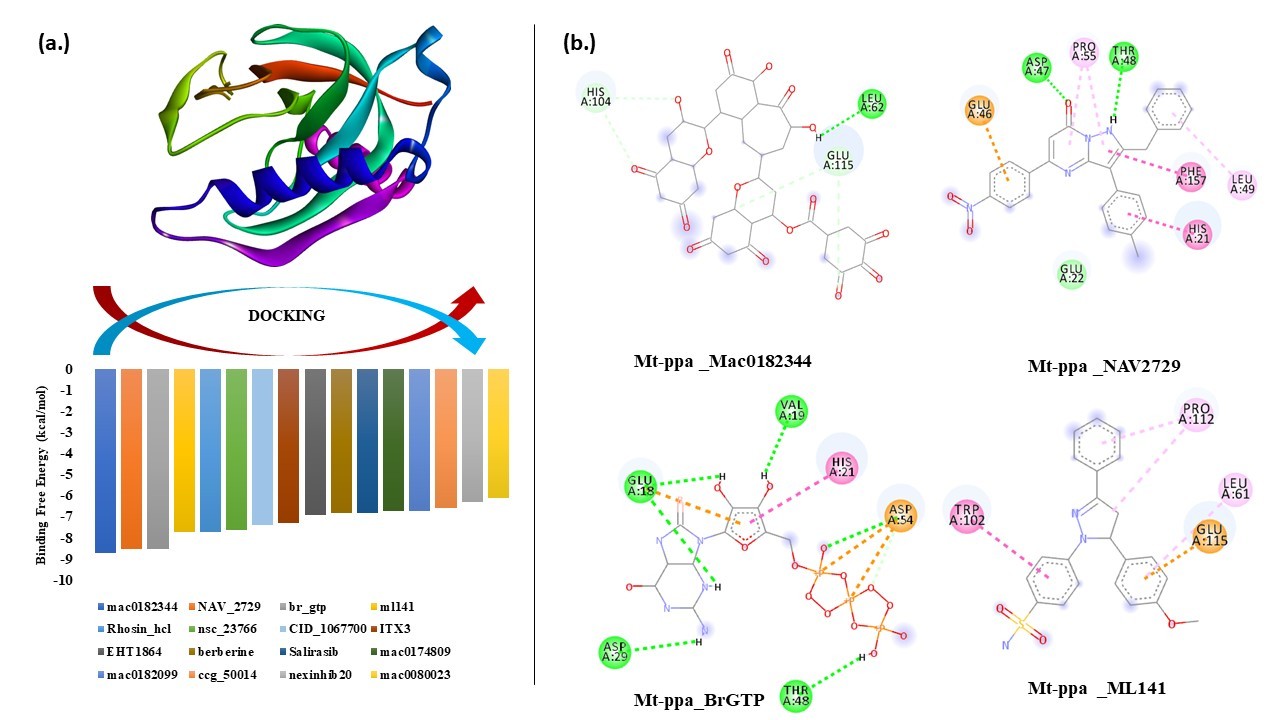

Screening of GTPase inhibitor: GTPase inhibitors inhibit the GTPase activity of a protein and thus may hinder the metabolism of the bacterium. The 16 inhibitors used in the study were Mac0182344, NAV_2729, Br_GTP, ML141, Rhosin_HCl, NSC_23766, CID_1067700, ITX3, EHT1864, Berberine, Salirasib, Mac0174809, Mac0182099, CCG_50014, Nexinhib20, Mac0080023. The highest binding affinity was seen in Mac0182344 and NAV_2729. Amongst the 16 inhibitors, 12 are characterized by chemical database set, the unknown compounds Mac0174809 and Mac0080023 are synthetic molecules and structural analogs whereas the other two compounds (Mac0182099 and Mac0182344) are natural products (Table 7).

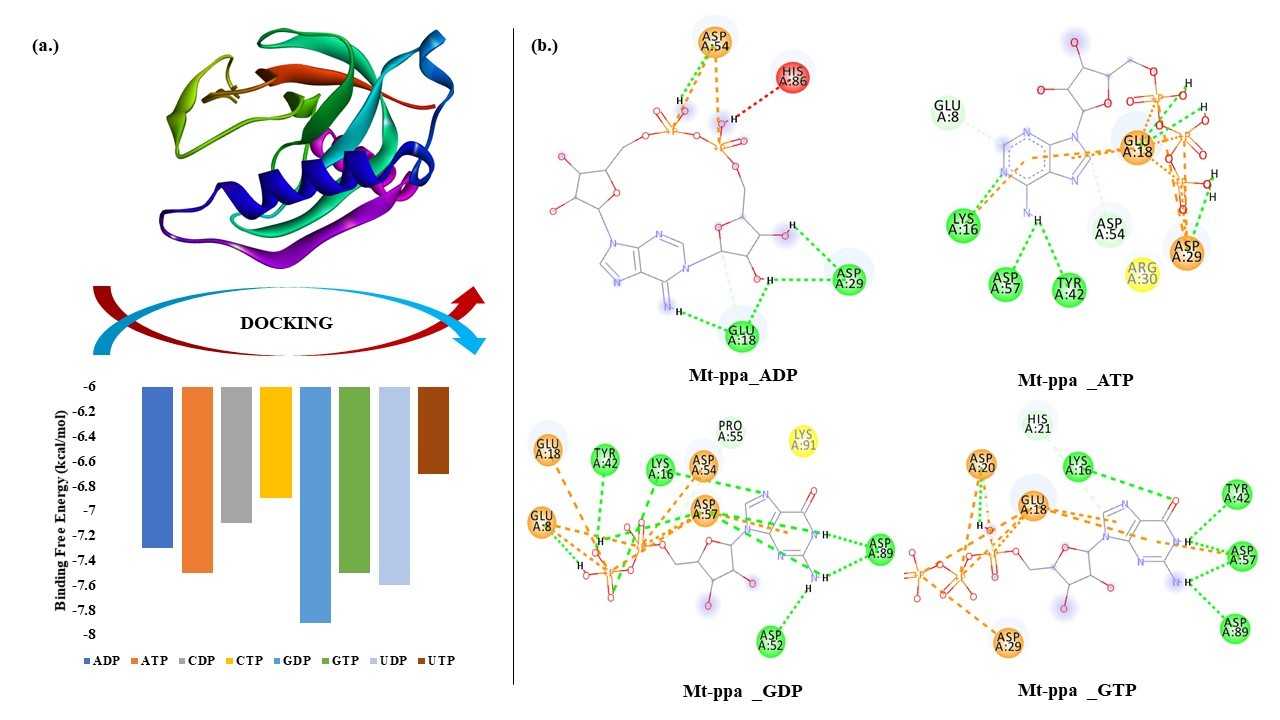

Docking of NTPs with Mt-PPa: Molecular docking was performed to check the binding of Mt-PPa with nucleotide tri and diphosphates. In the docking experiment, we found that Mt-PPa has the maximum binding affinity for Guanosine Di Phosphate (GDP) which was followed by UDP, GTP, ATP, ADP, CDP, CTP and UTP. The outcome of docking analysis showed that Mt-PPa has a higher affinity for diphosphates in comparison to triphosphates (Table 7).

|

S.No. |

Name of the ligand

|

Binding Free Energy (kcal/mol) |

pKi |

Ligand Efficiency (kcal/mol/non-H atom) |

|

NTDs |

||||

|

1 |

ATP |

-7.5 |

5.5 |

0.1562 |

|

2 |

ADP |

-7.3 |

5.35 |

0.1698 |

|

3 |

GTP |

-7.5 |

5.5 |

0.1531 |

|

4 |

GDP |

-7.9 |

5.79 |

0.1881 |

|

5 |

CDP |

-7.1 |

5.21 |

0.1775 |

|

6 |

CTP |

-6.9 |

5.06 |

0.1468 |

|

7 |

UDP |

-7.6 |

5.57 |

0.2 |

|

8 |

UTP |

-6.7 |

4.91 |

0.1489 |

|

GTPase Inhibitors |

||||

|

1 |

mac0182344 |

-8.7 |

6.38 |

0.1403 |

|

2 |

NAV_2729 |

-8.5 |

6.23 |

0.2125 |

|

3 |

br_gtp |

-8.5 |

6.23 |

0.1977 |

|

4 |

ml141 |

-7.7 |

5.65 |

0.2081 |

|

5 |

Rhosin-Hcl |

-7.7 |

5.65 |

0.2139 |

|

6 |

nsc_23766 |

-7.6 |

5.57 |

0.1727 |

|

7 |

CID_1067700 |

-7.4 |

5.43 |

0.2114 |

|

8 |

ITX3 |

-7.3 |

5.35 |

0.2355 |

|

9 |

EHT1864 |

-6.9 |

5.06 |

0.1438 |

|

10 |

berberine |

-6.8 |

4.99 |

0.2345 |

|

11 |

Salirasib |

-6.8 |

4.99 |

0.1789 |

|

12 |

mac0174809 |

-6.7 |

4.91 |

0.1136 |

|

13 |

mac0182099 |

-6.7 |

4.91 |

0.1031 |

|

14 |

ccg_50014 |

-6.6 |

4.84 |

0.2444 |

|

15 |

nexinhib20 |

-6.3 |

4.62 |

0.2172 |

|

16 |

mac0080023 |

-6.1 |

4.47 |

0.2259 |

|

Top ten Natural Inhibitors |

||||

|

1 |

ZINC000003780340 |

-9.7 |

7.11 |

0.2109 |

|

2 |

ZINC000003979028 |

-9.5 |

6.97 |

0.1827 |

|

3 |

ZINC000003870413 |

-9.4 |

6.89 |

0.2 |

|

4 |

ZINC000003870412 |

-9.2 |

6.75 |

0.1957 |

|

5 |

ZINC000150338758 |

-9.2 |

6.75 |

0.1108 |

|

6 |

ZINC000070450948 |

-9.1 |

6.67 |

0.175 |

|

7 |

ZINC000150338754 |

-9.1 |

6.67 |

0.1096 |

|

8 |

ZINC000095098891 |

-9 |

6.6 |

0.2368 |

|

9 |

ZINC000000119985 |

-9 |

6.6 |

0.3103 |

|

10 |

ZINC000005085286 |

-8.9 |

6.53 |

0.1561 |

Discussion

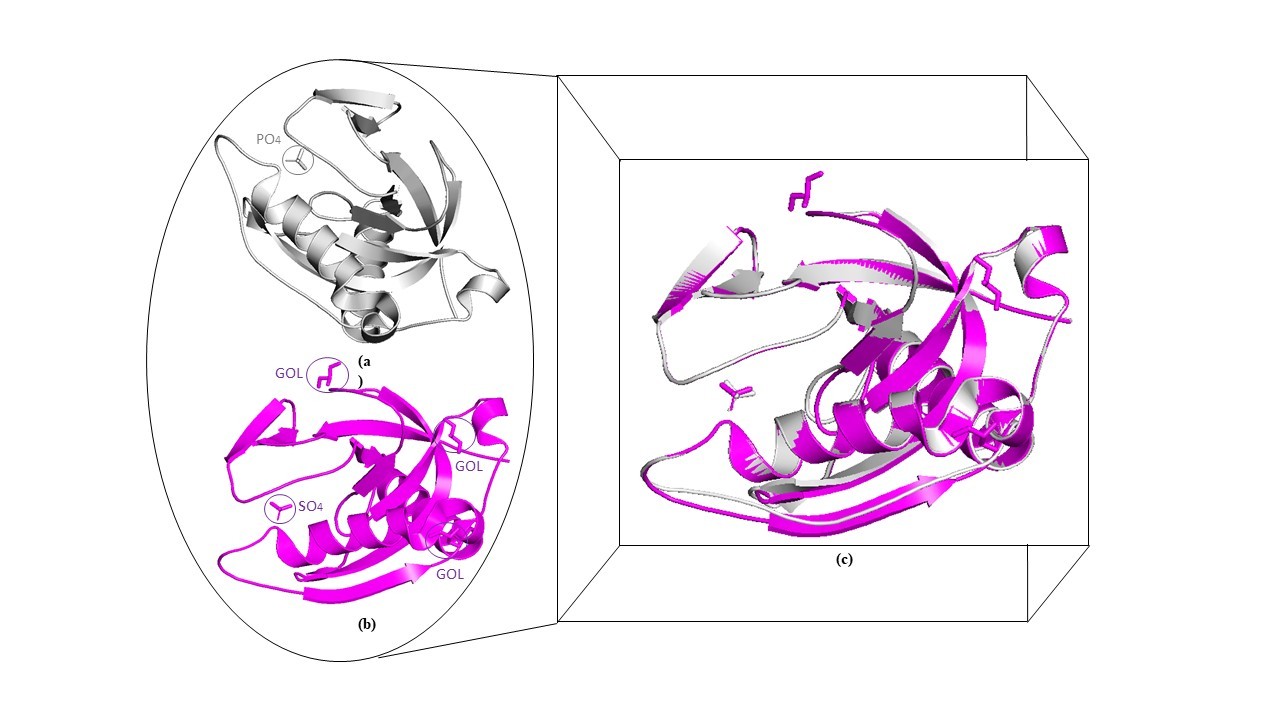

Tuberculosis is one of the major challenges among infectious diseases due to the emergence of drug-resistant variants. This disease majorly affects under developing countries, and this is due to various factors including poverty, malnutrition, lack of knowledge, lack of education and improper vaccination etc. [40]. The disease becomes more challenging with a coinfection like in the case of diabetes, HIV-AIDS, and most recent COVID-19 [41,42]. Therefore, deriving the proper medication against this malady is a primary need. This article is an attempt in the direction to deliver a more understanding view of Mtb virulence and survival strategy [42–44]. Soluble inorganic pyrophosphatases (ppa) are essential proteins in Mtb survival and depend on metal cofactor for their proper functioning in converting inorganic pyrophosphate to inorganic phosphate [45]. This conversion is a needy step in many biochemical reactions that yield pyrophosphate as a byproduct [46]. Therefore, its regulation is also an important step for proper Mtb metabolism and also this protein can utilize for targeting the metabolism of this pathogen. Mg2+ was found to be essential for the catalytic activity of PPa protein and in the absence of the Mg2+, there was loss of activity [12]. The protein was purified and the interaction of PPa with GTP was verified by ITC which showed that PPa interacted with GTP as a binder (Figure 1) and this result was further confirmed by molecular docking. The structure of Mt-PPa was retrieved from PDB whose PDB ID is 1WCF and 1SXV. The comparison between these structures was done by the overlapping of proteins (Figure 3). Active site residues were determined by CASTp server which is a mathematical algorithm-based server and counts on the structural appearance (Figure 4). Previous reports also established its role in NTPs hydrolysis [14]. This protein was found to have interacted with ATP synthase family proteins and its regulatory partner ptpA with high-affinity scores. ATP synthase family proteins were atpA, atpB, atpC, atpD, atpE, atpF, atpG and atpH. ATP family proteins are the essential molecules for Mycobacterium metabolism and its survival. The interaction of Mt-PPa with these proteins signifies their coordinating role in proper Mycobacterium functioning. The inorganic pyrophosphate released from any step of the ATP synthase reaction was converted into Pi by Mt-PPa to prevent bacteria from pyrophosphate cytotoxicity. Therefore, targeting this gene leads to automatically target the ATP gene family (Figure 2). The epitopic recognition was done by the BCpred server that determined 4 epitopes at different positions and T cell epitope prediction was done by the HLApred server. The prediction of epitope on Mt-PPa also suggests the immunological importance of Mt-PPa. The score of the epitope prediction showed that AADWVDRAEAEAEVQRSVER at position 137 with a score of 0.996 is the optimum epitopic region for B cell. Similarly, the top T cell epitopic region was DLEPGKFVK (Table 6). The protein showed strong binding with different ligand partners e.g. Mt-PPa has a strong binding affinity for ions such as SO42-, PO43-, K+, Ca2+ and Mn+. The binding of different ions resembles the protein dependability over these metal ions and Mt-PPa might utilize these metals as its cofactor for inorganic pyrophosphatase activity [16]. Further, we found that the protein phosphorylates at serine, threonine and tyrosine by different kinases. These phosphorylation’s might depict its transformed state which may be required for its activation (Table 5). Further mutational analysis revealed several mutational hits which will be required for targeting the essential points of this protein. By mutating those residues, the protein goes into a highly destabilized state. Those hits were as W102G, V150G, F44G, I119G, L93F, F3G, F122G, I108G, L32G, M82G, Y17G, L59G, V5G, V26G, I7G, W140D, W140G, W140A, F80G, W140S, L49G, L56G, I9G, V60G, V19G, V92G, L28G, L61G, Y126E, and F123G (Table 1). The CASTp server revealed that the active site of Mt-PPa comprises of 5 residues namely Y126G, Y42G, R30G, E8G, K16G (Table 2) and mutations at all 5 points and majorly at Y42 cause a large decrease in protein stability due to drastic disruption of interatomic interactions (Figure 5). Further on checking and verifying these mutations by different servers (PROVEAN and I Mutant 3.0), the same pattern of stability decrease was found. Mutual effect of mutations in Mt-PPa gene might be used for targeting this protein synthesis and functioning [47]. Improper synthesis and function thus lead to the accumulation of inorganic pyrophosphates in the Mycobacterium cytoplasm which may lead to cytotoxicity. Docking analysis showed that Mt-PPa is more preserved for diphosphate nucleotides in comparison to triphosphate nucleotides (Figure 6).

Figure 3. Comparison of 1WCF and 1SXV: The structural information of Ppa was extracted from two PDB databases was compared to analyze any difference between them.

Figure 4. Active site residue prediction: Active site was predicted by CASTp server and R30, K16, Y12, E8 and Y42 are the residues that are present in the active site.

Figure 5. Structure based mutation: Structure based mutation analysis was done on active site residues. All mutations show decreased protein dynamic stability due to disruption of interatomic interactions. The highest decreased stability was due to Y42G substitution which is shown in the separate diagram.

Figure 6. Docking of Mt-PPa with nucleotides: (a.) Binding energy graph: Mt-PPa was docked with all nucleotides in INSTADOCK server, and it was found that Mt-PPa docked with all nucleotides in the order of GDP>UDP>GTP>ATP>ADP>CDP>CTP>UTP. (b.) Interaction analysis: Interaction analysis between Mt-PPa and two major signaling molecules (ATP and GTP) and their dinucleotides was done by pymol visualization server. There was extensive hydrogen bonding that was seen in all interactions.

Virtual screening and docking analysis showed that GTPase inhibitors also reacted with PPa with the highest affinity showed by Mac0182344, NAV_2729, Br-GTP and ML-141 (Figure 7). Mac0182344 is a natural compound that also showed the inhibitory effect on M. tuberculosis EngA which is a universally conserved GTPase protein [47]. The minimum inhibitory concentration that kills 50% of total bacteria was 4.6 µM for Mac0182344. NAV_2729 is an ARF6 inhibitor with IC50 value of 1.0 µM and it binds at the GEF binding area and does not overlap with the nucleotide-binding pocket of ARF6. The complex of inhibitor and ARF6 was stabled by the formation of hydrogen bonds at Lys58 residue and inhibitor carbonyl group and ε-amino group. The major contributors to the inhibitor-binding energy are Phe47, Trp62, Trp74, and Tyr77. Virtual screening with herbal ingredients targets showed ZINC000003780340, ZINC000003979028, ZINC000003870413, ZINC000003870412, ZINC000150338758, ZINC0000070450948, ZINC000150338754, ZINC000095098891, ZINC000000119985, ZINC000005085286 as the top ten hits that target PPa protein with highest binding energy (Figure 8) [48]. The Lipinski rule of 5 was applied to these compounds to confirm their effectiveness as drugs (Table 8). The properties of these compounds were searched through Pass online (way2drug) server that was used for finding involvement of the protein in different biological activity, including pharmacological effects, mechanisms of action, toxic and adverse effects, interaction with metabolic enzymes and transporters, influence on gene expression, etc. The top results were in (Table 9) where Pa and Pi refer to probability being active and inactive respectively. Absorption and toxicity prediction was also done by SWISS-ADME and ADME-SAR which showed that absorbance of ZINC000000119985 was high and there was compound involved as blood-brain barrier and all are non-carcinogens [48] (Table 10). These compounds can be used as potential natural targets to conquer Mt-PPa protein functioning and thus halt Mtb metabolism and its survival. The docking analysis of Mt-PPa with different nucleotides showed that Mt-PPa also binds with other nucleotides and greatly with the diphosphates (GDP) [49,50]. The docking analysis showed the maximum binding of PPa with GDP with the docking score -7.9 kcal/mol however, its docking value with GTP was -7.5 kcal/mol. So, there was not much difference in the docking value of PPa with the ligands and GDP interaction with PPa might be led to product inhibition of GTP hydrolysis reaction. But this phenomenon should be analyzed by in vitro mechanisms. Nucleotide binding mechanism is thus representing a window for the novel targeting mechanisms that must be studied and explored as they are the important pathways for mycobacterial survival also [51,52].

This article provides insights into the essential features of Mt-PPa, highlighting potential molecular targets and mechanisms to fully inhibit its function. Given that bacterial PPases are vital enzymes for cellular survival, they represent promising candidates for small-molecule inhibitions. Identification of such inhibitors should be facilitated by the advancement of assays amenable to high-throughput screening technologies (HTS).

Figure 7. Docking of Mt-PPa with GTPase inhibitors: (a.) Binding energy graph: Mt-PPa was docked with known GTPase inhibitors in INSTADOCK server, and it was found that Mt-PPa was significantly docked with all inhibitors. (b.) Interaction analysis: Interaction analysis between Mt-PPa and top hits of inhibitors was checked. Mac0182344, NAV2729, Br GTP and ML141 were the top hits of inhibitors that were indulged in the interaction by hydrogen, alkyl and van der Waals interaction.

Figure 8. Docking of Mt-PPa with HITs: (a.) Binding energy graph: Mt-PPa was docked with known HITs subset of ZINC database in INSTADOCK server, and it was found that Mt-PPa was docked with all HIT compounds and top hits were further checked for interaction analysis. (b.) Interaction analysis: Interaction analysis between Mt-PPa and top hits of HIT compounds was checked. ZINC000003780340, ZINC000003979028, ZINC000003870413, ZINC000003870412 were the top hits of HIT compounds that were indulged in the interaction by hydrogen, alkyl and van der Waals interaction.

|

Name of the ligand |

Binding Free Energy (kcal/mol) |

MW g/mol |

RB |

HA |

HD |

logP |

Vio |

|

ZINC000003780340 |

-9.7 |

504.44 |

0 |

8 |

6 |

3.13 |

2 |

|

ZINC000003979028 |

-9.5 |

458.37 |

4 |

11 |

8 |

1.83 |

2 |

|

ZINC000003870413 |

-9.4 |

458.37 |

4 |

11 |

8 |

1.83 |

2 |

|

ZINC000003870412 |

-9.2 |

458.37 |

4 |

11 |

8 |

1.53 |

2 |

|

ZINC000150338758 |

-9.2 |

864.76 |

4 |

18 |

14 |

2.52 |

3 |

|

ZINC000070450948 |

-9.1 |

564.54 |

6 |

9 |

2 |

4.78 |

1 |

|

ZINC000150338754 |

-9.1 |

864.76 |

4 |

18 |

14 |

2.52 |

3 |

|

ZINC000095098891 |

-9 |

456.70 |

1 |

3 |

2 |

3.90 |

1 |

|

ZINC000000119985 |

-9 |

290.27 |

1 |

6 |

5 |

1.36 |

0 |

|

ZINC000005085286 |

-8.9 |

578.52 |

3 |

12 |

10 |

2.23 |

3 |

|

Name of the ligand |

Pa |

Pi |

Activity |

|

ZINC000003780340 |

0,912 |

0,009 |

CYP2C12 substrate |

|

ZINC000003979028 |

0,969 |

0,002 |

HMOX1 expression enhancer |

|

ZINC000003870413 |

0,969 |

0,002 |

HMOX1 expression enhancer |

|

ZINC000003870412 |

0,969 |

0,002 |

HMOX1 expression enhancer |

|

ZINC000150338758 |

0,968 |

0,002 |

Membrane integrity agonist |

|

ZINC000070450948 |

0,961 |

0,001 |

CYP1A inducer |

|

ZINC000150338754 |

0,968 |

0,002 |

Membrane integrity agonist |

|

ZINC000095098891 |

0,984 |

0,002 |

Caspase 3 stimulant |

|

ZINC000000119985 |

0,983 |

0,001 |

Membrane integrity agonist |

|

ZINC000005085286 |

0,968 |

0,002 |

Membrane integrity agonist |

|

Name of the ligand |

GI abs. |

BBB |

Log Kp (cm/s) |

AMES toxicity (A.T) |

Carcinogens |

|

ZINC000003780340 |

Low |

No |

-4.48 |

A.T |

Non-C |

|

ZINC000003979028 |

Low |

No |

-8.27 |

Non-A.T |

Non-C |

|

ZINC000003870413 |

Low |

No |

-8.27 |

Non-A.T |

Non-C |

|

ZINC000003870412 |

Low |

No |

-8.27 |

Non-A.T |

Non-C |

|

ZINC000150338758 |

Low |

No |

-9.21 |

Non-A.T |

Non-C |

|

ZINC000070450948 |

Low |

No |

-5.61 |

Non-A.T |

Non-C |

|

ZINC000150338754 |

Low |

No |

-9.21 |

Non-A.T |

Non-C |

|

ZINC000095098891 |

Low |

No |

-3.77 |

Non-A.T |

Non-C |

|

ZINC000000119985 |

High |

No |

-7.82 |

Non-A.T |

Non-C |

|

ZINC000005085286 |

Low |

No |

-9.30 |

Non-A.T |

Non-C |

Conclusion

This manuscript describes the essential roles of mycobacterial inorganic pyrophosphatases (PPa). Given the increasing incidence of tuberculosis and the growing challenge of drug resistance, the identification of novel drug targets is of critical importance. Despite decades of continuous research, the development of effective vaccines or therapeutics capable of fully curing this disease remains challenging.

In this study, we highlight the potential of PPa as a druggable target, as it is an essential mycobacterial protein required for both in vitro and in vivo survival [52]. We also identify key mutational hotspots within the gene, including those located in the active sites, which significantly reduce protein stability. All examined mutations led to a marked decrease in PPa stability.

Furthermore, we evaluated the interaction of natural compounds and GTPase inhibitors with the PPa protein. Both groups demonstrated strong binding affinities. Among the GTPase inhibitors, Mac0182344 and NAV_2729 emerged as the top candidates. From the natural compound library, the highest-affinity binders were ZINC000003780340, ZINC000003979028, ZINC000003870413, ZINC000003870412, ZINC000150338758, ZINC0000070450948, ZINC000150338754, ZINC000095098891, ZINC000000119985, and ZINC000005085286.

Collectively, these findings provide valuable insights and establish a foundation for the discovery of potential therapeutic targets involving mycobacterial inorganic pyrophosphatases.

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge financial support from the Department of Science and Technology-SERB, Council of Scientific and Industrial Research-Institute of Genomics and Integrative Biology under the research project GAP0145 (SERB-DST Grant no: EEQ/2016/000514).

Declaration

Funding

The work is supported by Department of Science and Technology-SERB, Council of Scientific and Industrial Research-Institute of Genomics and Integrative Biology under the research project GAP0145 (SERB-DST Grant no: EEQ/2016/000514).

Competing/conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest.

Author contributions

Shivangi conceptually analyzed the work, wrote the manuscript, designed and generated figures; and LSM helped in writing, correctness, and handled all the corresponding activities.

Data availability statement

Yes, the authors agreed that the availability of data ensures data transparency norms.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Consent to publish

Yes, all authors have given their consent.

References

2. Triccas JA, Gicquel B. Life on the inside: probing Mycobacterium tuberculosis gene expression during infection. Immunol Cell Biol. 2000 Aug;78(4):311–7.

3. Kornberg A. Horizons in Biochemistry. Kasha H, Pullman B, editors. New York: Academic Press; 1962. pp. 251–64.

4. Triccas JA, Gicquel B. Analysis of stress- and host cell-induced expression of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis inorganic pyrophosphatase. BMC Microbiol. 2001;1:3.

5. de Meis L. Pyrophosphate of high and low energy. Contributions of pH, Ca2+, Mg2+, and water to free energy of hydrolysis. J Biol Chem. 1984 May 25;259(10):6090–7.

6. Flodgaard H, Fleron P. Thermodynamic parameters for the hydrolysis of inorganic pyrophosphate at pH 7.4 as a function of (Mg2+), (K+), and ionic strength determined from equilibrium studies of the reaction. J Biol Chem. 1974 Jun 10;249(11):3465–74.

7. Baykov AA, Shestakov AS, Kasho VN, Vener AV, Ivanov AH. Kinetics and thermodynamics of catalysis by the inorganic pyrophosphatase of Escherichia coli in both directions. Eur J Biochem. 1990 Dec 27;194(3):879–87.

8. Kajander T, Kellosalo J, Goldman A. Inorganic pyrophosphatases: one substrate, three mechanisms. FEBS Lett. 2013 Jun 27;587(13):1863–9.

9. Chen J, Brevet A, Fromant M, Lévêque F, Schmitter JM, Blanquet S, et al. Pyrophosphatase is essential for growth of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1990 Oct;172(10):5686–9.

10. Gajadeera CS, Zhang X, Wei Y, Tsodikov OV. Structure of inorganic pyrophosphatase from Staphylococcus aureus reveals conformational flexibility of the active site. J Struct Biol. 2015 Feb;189(2):81–6.

11. Merckel MC, Fabrichniy IP, Salminen A, Kalkkinen N, Baykov AA, Lahti R, et al. Crystal structure of Streptococcus mutans pyrophosphatase: a new fold for an old mechanism. Structure. 2001 Apr 4;9(4):289–97.

12. Rantanen MK, Lehtiö L, Rajagopal L, Rubens CE, Goldman A. Structure of the Streptococcus agalactiae family II inorganic pyrophosphatase at 2.80 A resolution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2007 Jun;63(Pt 6):738–43.

13. Sivula T, Salminen A, Parfenyev AN, Pohjanjoki P, Goldman A, Cooperman BS, et al. Evolutionary aspects of inorganic pyrophosphatase. FEBS Lett. 1999 Jul 2;454(1-2):75–80.

14. Benini S, Wilson K. Structure of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis soluble inorganic pyrophosphatase Rv3628 at pH 7.0. Acta Crystallogr Sect F Struct Biol Cryst Commun. 2011 Aug 1;67(Pt 8):866–70.

15. Tammenkoski M, Benini S, Magretova NN, Baykov AA, Lahti R. An unusual, His-dependent family I pyrophosphatase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Biol Chem. 2005 Dec 23;280(51):41819–26.

16. Rodina EV, Vainonen LP, Vorobyeva NN, Kurilova SA, Sitnik TS, Nazarova TI. Metal cofactors play a dual role in Mycobacterium tuberculosis inorganic pyrophosphatase. Biochemistry (Mosc). 2008 Aug;73(8):897–905.

17. Pratt AC, Dewage SW, Pang AH, Biswas T, Barnard-Britson S, Cisneros GA, et al. Structural and computational dissection of the catalytic mechanism of the inorganic pyrophosphatase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Struct Biol. 2015 Oct;192(1):76–87.

18. Beg A, Khan FI, Lobb KA, Islam A, Ahmad F, Hassan MI. High throughput screening, docking, and molecular dynamics studies to identify potential inhibitors of human calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IV. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2019 May;37(8):2179–92.

19. Meena LS, Chopra P, Bedwal RS, Singh Y. Cloning and characterization of GTP-binding proteins of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2008 Jan;42(2):138–44.

20. Meena LS, Rajni. Cloning and characterization of engA, a GTP-binding protein from Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv. Biologicals. 2011 Mar;39(2):94–9.

21. Gast K, Damaschun G, Misselwitz R, Zirwer D. Application of dynamic light scattering to studies of protein folding kinetics. Eur Biophys J. 1992;21(5):357–62.

22. Pierce MM, Raman CS, Nall BT. Isothermal titration calorimetry of protein-protein interactions. Methods. 1999 Oct;19(2):213–21.

23. Sharma K, Gupta M, Krupa A, Srinivasan N, Singh Y. EmbR, a regulatory protein with ATPase activity, is a substrate of multiple serine/threonine kinases and phosphatase in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. FEBS J. 2006 Jun;273(12):2711–21.

24. Meena LS, Beg MA. Insights of Rv2921c (Ftsy) gene of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv to prove its significance by computational approach. Biomed J of Sci & Tech Res. 2018;12(2):9147–57.

25. Sanchez-Trincado JL, Gomez-Perosanz M, Reche PA. Fundamentals and Methods for T- and B-Cell Epitope Prediction. J Immunol Res. 2017;2017:2680160.

26. Beg MA, Shivangi, Athar F, Meena LS. Structural and Functional Annotation of Rv1514c Gene of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv As Glycosyl Transferases. J Adv Res Biotech. 2018;3(2):1–9.

27. Beg MA, Shivangi, Sonu CT, Meena LS. Systematical Analysis to Assist the Significance of Rv1907c Gene with the Pathogenic Potentials of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv. J Biotechnol Biomater. 2019;8:286.

28. Beg MA, Shivangi, Thakur SC, Meena LS. Structural Prediction and Mutational Analysis of Rv3906c Gene of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv to Determine Its Essentiality in Survival. Adv Bioinformatics. 2018 Aug 15; 2018:6152014.

29. Barberis E, Marengo E, Manfredi M. Protein Subcellular Localization Prediction. Methods Mol Biol. 2021;2361:197–212.

30. Konc J, Miller BT, Štular T, Lešnik S, Woodcock HL, Brooks BR, et al. ProBiS-CHARMMing: Web Interface for Prediction and Optimization of Ligands in Protein Binding Sites. J Chem Inf Model. 2015 Nov 23;55(11):2308–14.

31. Zhou H, Skolnick J. FINDSITE (comb): a threading/structure-based, proteomic-scale virtual ligand screening approach. J Chem Inf Model. 2013 Jan 28;53(1):230–40.

32. Buchan DWA, Jones DT. The PSIPRED Protein Analysis Workbench: 20 years on. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019 Jul 2;47(W1):W402–7.

33. Beg MA, Meena LS. Mutational effects on structural stability of SRP pathway dependent co-translational protein ftsY of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv. Gen Rep. 2019 Jun 1;15:100395.

34. Tian W, Chen C, Lei X, Zhao J, Liang J. CASTp 3.0: computed atlas of surface topography of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018 Jul 2;46(W1):W363–7.

35. Pires DE, Ascher DB, Blundell TL. DUET: a server for predicting effects of mutations on protein stability using an integrated computational approach. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014 Jul;42(Web Server issue):W314–9.

36. Gautam P, Shivangi, Meena LS. Revelation of point mutations effect in Mycobacterium tuberculosis MfpA protein that involved in mycobacterial DNA supercoiling and fluoroquinolone resistance. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 2020 Oct 23.

37. Mohammad T, Mathur Y, Hassan MI. InstaDock: A single-click graphical user interface for molecular docking-based virtual high-throughput screening. Brief Bioinform. 2021 Jul 20;22(4): bbaa279.

38. Hassan NM, Alhossary AA, Mu Y, Kwoh CK. Protein-Ligand Blind Docking Using QuickVina-W With Inter-Process Spatio-Temporal Integration. Sci Rep. 2017 Nov 13;7(1):15451.

39. O'Boyle NM, Banck M, James CA, Morley C, Vandermeersch T, Hutchison GR. Open Babel: An open chemical toolbox. J Cheminform. 2011 Oct 7;3:33.

40. Shivangi, Meena LS. Calcium ATPase signaling: A must include mechanism in the Radar of therapeutics development against Tuberculosis. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 2020 Sep 25.

41. Shivangi, Meena LS. A Novel Approach in Treatment of Tuberculosis by Targeting Drugs to Infected Macrophages Using Biodegradable Nanoparticles. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2018 Jul;185(3):815–21.

42. Yang H, Lu S. COVID-19 and Tuberculosis. J Transl Int Med. 2020 Jun 25;8(2):59–65.

43. Shivangi KN, Meena LS. Distinctive features of microvesicles as a transporter of GTP and iron to empower pathogenesis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv. Emerg Infect Dis Diag. 2020;2020:J EIDDJ–100009.

44. Shivangi & Meena LS. To target the PI3-Kinase pathway of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv phagosome by heavy metal ions. 37. Res Rev J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2019;8(3).

45. Zhou L, Ma C, Xiao T, Li M, Liu H, Zhao X, et al. A New Single Gene Differential Biomarker for Mycobacterium tuberculosis Complex and Non-tuberculosis Mycobacteria. Front Microbiol. 2019 Aug 13;10:1887.

46. Pratt AC, Dewage SW, Pang AH, Biswas T, Barnard-Britson S, Cisneros GA, et al. Structural and computational dissection of the catalytic mechanism of the inorganic pyrophosphatase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Struct Biol. 2015 Oct;192(1):76–87.

47. Pang AH, Garzan A, Larsen MJ, McQuade TJ, Garneau-Tsodikova S, Tsodikov OV. Discovery of Allosteric and Selective Inhibitors of Inorganic Pyrophosphatase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. ACS Chem Biol. 2016 Nov 18;11(11):3084–92.

48. Bharat A, Blanchard JE, Brown ED. A high-throughput screen of the GTPase activity of Escherichia coli EngA to find an inhibitor of bacterial ribosome biogenesis. J Biomol Screen. 2013 Aug;18(7):830–6.

49. Meena LS, Rajni. Survival mechanisms of pathogenic Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv. FEBS J. 2010 Jun;277(11):2416–27.

50. Rajni, Meena LS. Guanosine triphosphatases as novel therapeutic targets in tuberculosis. Int J Infect Dis. 2010 Aug;14(8): e682–7.

51. Verma H, Shivangi, Meena LS. Delivery of antituberculosis drugs to Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv infected macrophages via polylactide-co-glycolide (PLGA) nanoparticles. Int J Mol Biol Open Access. 2018;3(5):235–8.

52. Tanwar P, Shivangi, Meena LS. Cholesterol Metabolism: As a Promising Target Candidate for Tuberculosis Treatment by Nanomedicine. J. Nanomater. Mol. Nanotechnol. 2019;8(2).