Abstract

Background: In South Africa, new amended regulations required a review of complementary and alternative medicine (CAMs) call-up for registration from November 2013. This impacted traditional healers (THs)’ compliance with the regulatory authorities’ on the good manufacturing practice which in return affected the public’s access to CAMs. This investigation embraces methods, THs use to diagnose and treat diabetes (DM) in Mamelodi. Furthermore, it assesses what their purported medications comprise of. It is fundamental to understand the functioning of the South African Health Products Regulatory Agency (SAHPRA). Regulations surrounding registration and post-marketing control of CAMs are crucial, needing a solution.

Method: The study comprised of dedicated questionnaires, distributed amongst THs to gain knowledge on their diagnosis and identify the CAMs used. It also included non-structured surveys on pharmacies to identify and assess compliance of those CAMs with the SAHPRA (previously Medicines Control Council (MCC)) regulations.

Result: TH’s do not use any medical tests or materials for diagnosis. They use skeletal bones and prayers. Most CAMs found in the pharmacies have a disclaimer on the label when not evaluated by MCC/SAHPRA. Only two medicines were registered: ‘Manna blood sugar support and super moringa’. Self-provided TH treatment list for DM displays 20 different active ingredients in various CAM therapies. The most common treatment used is a plant and herbal-based (Muti) such as 1-ounce (Oz) mixture.

Conclusion: Diagnosis of diabetes by THs is mostly done by divination. TH’s have an understanding with regards to drug safety, are aware of regulations but do not comply with SAHPRA. Their purported medication seems to be successful, according to themselves but further investigation and proper collaboration between the THs and bodies is in demand. Future study is needed by a competent researcher with traditional medicine qualifications.

Keywords

Diagnostic imaging, Magnetic resonance imaging, Elbow tendinopathy, Tennis elbow, Early diagnosis

Case Report

A 59-year-old left hand dominant female was evaluated by a physical therapist. The patient had an 8-year history of chronic intermittent left elbow pain with a recent exacerbation occurring after moving furniture. Aggravating factors included holding a coffee cup, picking up trash bags, and lifting heavy dishes. Symptoms were eased by ice and Meloxicam as prescribed by her primary care provider.

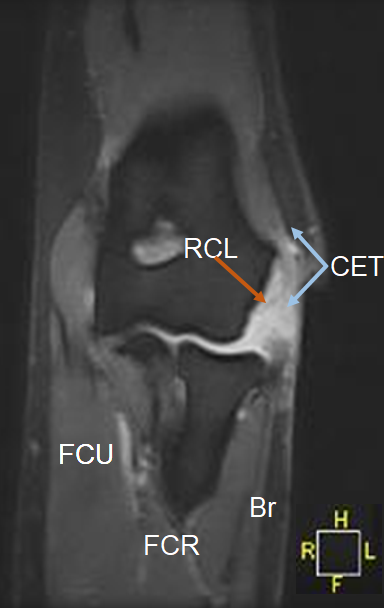

The left lateral elbow inferior to the lateral epicondyle had moderate edema and mild ecchymosis. Resisted wrist extension was weak and painful. Large grip and stretching of the wrist extensors reproduced mild pain. The common extensor tendon (CET) and the lateral epicondyle were tender to palpation. Passive accessory motion was positive for hypermobility of the proximal radioulnar joint. Due to concern for an atraumatic CET tear, the physical therapist performed a same-day magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examination on a 0.25 Tesla Esaote G-Scan Brio.

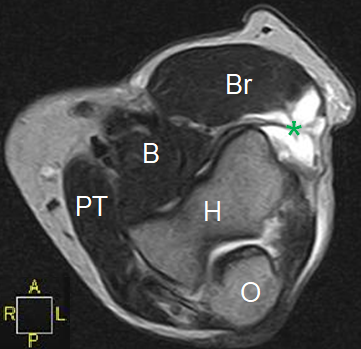

The MRI scan demonstrated a CET rupture and radial collateral ligament tear, which was subsequently confirmed via radiology consult (Figures 1 and 2). The patient was referred to an orthopedic surgeon where she was offered surgical intervention. In this case, a physical therapist was able to expedite the diagnostic process by operating a low-field MRI unit in the clinic. Total time elapsed between physical therapy evaluation, completion of the MRI, and orthopedic consultation was seven days. Clinical reasoning by a physical therapist and access to a musculoskeletal MRI expedited a robust referral to an orthopedic surgeon. Traditional pathways can comparably delay care by one year [1].

Figure 1. Coronal short tau inversion recovery magnetic resonance image of the left elbow demonstrating a rupture of the common extensor tendon (CET) with 1.35cm retraction and a full thickness tear of the radial collateral ligament (RCL). Flexor Carpi Ulnaris (FCU); Flexor Carpi Radialis (FCR); Brachioradialis (Br).

Figure 2. Axial T2 weighted magnetic resonance image of the left elbow demonstrating high signal intensity (*) and absence of muscular and tendinous signal consistent with a ruptured and retracted common extensor tendon. Brachialis (B); Brachioradialis (Br); Pronator Teres (PT); Humerus (H); Olecranon (O).

Many physical therapists within the United States of America are restricted from referring patients directly to a radiologist by their respective state practice acts or state physical therapy board rules [2]. However, when physical therapists are authorized to refer for imaging, they do so appropriately [3,4], accurately [5], and without harm to patients [6]. While physical therapists are often prohibited from performing imaging techniques that expose the patient to radiation, few restrictions in performing imaging techniques without ionizing radiation exist [7]. Therefore, clinical utilization of low-field MRI by physical therapists may be a viable future for this imaging modality and could facilitate diagnosis and timely therapeutic interventions.

Low-field MRI has gained recent popularity due to its relative low cost, its ability to perform both weight-bearing and non-weight-bearing images, its comparable safety profile, and its ability to perform open imaging while maintaining excellent correlation with higher field magnets [8]. While still a relatively new and somewhat unexplored modality, low-field MRI has shown the potential for promising innovations including intraoperative capabilities and the promise of portable MRI units [9]. Low-field MRI does have limitations, however, as greater imaging times and higher signal to noise ratios can lead to greater artifact.

Low-field MRI has shown promise in diagnosing conditions such as degenerative disc disease [8]. Its efficacy in identifying bone marrow edema has been demonstrated in rheumatologic and connective tissue disorders [10]. However, its diagnostic capability has not been well established for all orthopedic conditions. Studies comparing the diagnostic accuracy of low-field MRI to MRI with more powerful magnets in the diagnosis of orthopaedic conditions are needed.

Conflict of Interest

We affirm that we have no financial affiliation (including research funding) or involvement with any commercial organization that has a direct financial interest in any matter included in this manuscript. No other conflict of interest (i.e., personal associations or involvement as a director, officer, or expert witness) exists.

Funding

No grant support was attained or utilized in regard to this manuscript.

References

2. Mabry LM, Boyles RE, Brismée JM, Agustsson H, Smoliga JM. Physical therapy musculoskeletal imaging authority: A survey of the World Confederation for Physical Therapy Nations. Physiotherapy Research International. 2020 Apr;25(2):e1822.

3. Crowell MS, Dedekam EA, Johnson MR, Dembowski SC, Westrick RB, Goss DL. Diagnostic imaging in a directaccess sports physical therapy clinic: a 2-year retrospective practice analysis. International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy. 2016 Oct;11(5):708.

4. Keil A, Brown SR. US hospital-based direct access with radiology referral: an administrative case report. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice. 2015 Nov 17;31(8):594- 600.

5. Moore JH, Goss DL, Baxter RE, DeBerardino TM, Mansfield LT, Fellows DW, et al. Clinical diagnostic accuracy and magnetic resonance imaging of patients referred by physical therapists, orthopaedic surgeons, and nonorthopaedic providers. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2005 Feb;35(2):67-71.

6. Mabry LM, Notestine JP, Moore JH, Bleakley CM, Taylor JB. Safety events and privilege utilization rates in advanced practice physical therapy compared to traditional primary care: an observational study. Military Medicine. 2020 Jan;185(1-2):e290-7.

7. Boyles RE, Gorman I, Pinto D, Ross MD. Physical therapist practice and the role of diagnostic imaging. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2011 Nov;41(11):829-37.

8. Lee RK, Griffith JF, Lau YY, Leung JH, Ng AW, Hung EH, Law SW. Diagnostic capability of low-versus highfield magnetic resonance imaging for lumbar degenerative disease. Spine. 2015 Mar 15;40(6):382-91.

9. Lother S, Schiff SJ, Neuberger T, Jakob PM, Fidler F. Design of a mobile, homogeneous, and efficient electromagnet with a large field of view for neonatal lowfield MRI. Magnetic Resonance Materials in Physics, Biology and Medicine. 2016 Aug;29(4):691-8.

10. Chiara T, Niccolò P, Davide C, Stefano B, Marta M. MRI pattern of arthritis in systemic lupus erythematosus: a comparative study with rheumatoid arthritis and healthy subjects. Skeletal Radiology. 2015 Feb;44(2):261-6.