Abstract

The article "USP50 regulates NLRP3 inflammasome activation in duodenogastric reflux-induced gastric tumorigenesis" published in Frontiers in Immunology, has greatly piqued our curiosity. Zhao et al. describe how bile acids elevate ubiquitin-specific protease 50 (USP50) in macrophages, facilitating NLRP3 inflammasome assembly, HMGB1 release, and activation of PI3K/AKT and MAPK/ERK pathways that may promote gastric cancer progression. In their study, the authors used multiple cell lines for in vitro analyses, including the murine macrophage line RAW264.7, human monocytic U937 cells, and human embryonic kidney 293T cells. They reported detectable ASC protein in RAW264.7 cells and utilized U937 and 293T cells for key ASC-focused mechanistic assays (e.g., ASC-USP50 interaction, ASC specks formation, ASC oligomerization, and ASC ubiquitination); additionally, canonical readouts of inflammasome activation (including cleaved caspase-1 and mature IL-1β) were reported in RAW264.7 cells. However, ample evidence confirms that RAW264.7 cells lack ASC expression due to epigenetic silencing and are widely recommended as a negative control for ASC detection. Thus, the detection of ASC signals and downstream inflammasome activation in RAW264.7 cells is inconsistent with established characteristics of this cell line, and this discrepancy may stem from antibody cross-reactivity, cell contamination, or inaccurate cell line characterization. Notably, this limitation is specific to the RAW264.7-based ASC-dependent inflammasome experiments and does not affect the validity of other key findings in Zhao et al.’s study, including in vivo mouse data, clinical sample analyses, and investigations into the PI3K/AKT and ERK tumor-related pathways. Thus, verification of RAW264.7 cell line identity and ASC expression status is essential solely for consolidating the ASC-related inflammasome conclusions.

Keywords

ASC, Gastric tumorigenesis, Pyroptosis, USP50

Introduction

The recent study by Zhao et al. in Frontiers in Immunology reported that bile acids induce USP50 expression in macrophages, which then deubiquitinates ASC to promote NLRP3 inflammasome activation and HMGB1 release, ultimately driving gastric cancer progression through PI3K/AKT and MAPK/ERK pathways [1]. These findings provide valuable insights into the potential role of bile reflux-driven inflammation in the pathogenesis of gastric cancer. In general, this is an insightful piece of research. However, there are a few points in the paper that require further discussion and critical examination.

Results and Discussion

The RAW264.7 cell line, a murine macrophage model, is widely utilized in in vitro studies focusing on inflammatory mechanisms and immune regulation [2]. However, the intrinsic deficiency in ASC (apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD domain), a key molecular attribute inherent to this cell line, has not been adequately considered in some studies, which is critical for ensuring experimental rigor. The lack of attention to this characteristic impairs the rationality of experimental design [3], the authenticity of results, and the credibility of mechanistic interpretations. A notable example is the study by Zhao et al. investigating "USP50 regulates NLRP3 inflammasome activation in duodenogastric reflux-induced gastric tumorigenesis," which highlights this issue [1].

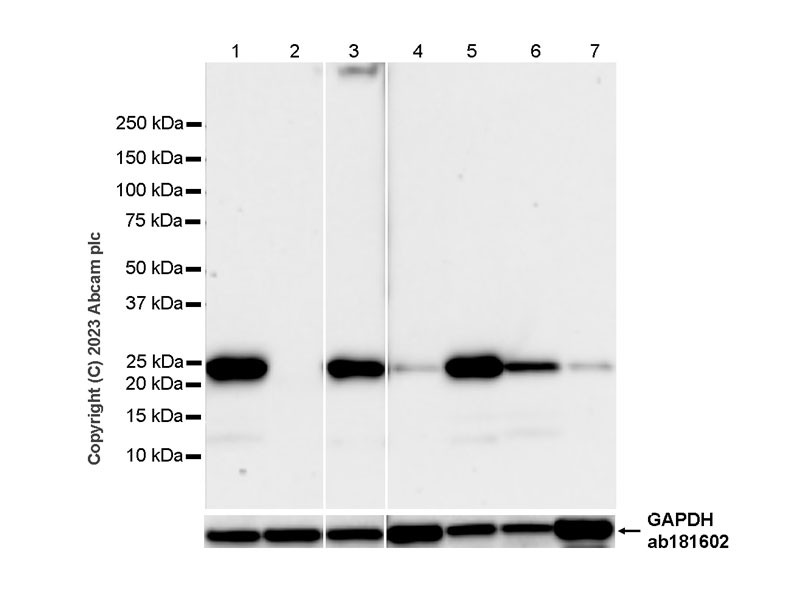

From the perspective of molecular mechanisms, ASC serves as the core hub for the assembly and functional activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. In the canonical NLRP3 inflammasome activation pathway, NLRP3 proteins first form a basic complex through self-oligomerization and then must bind to ASC. Specifically, ASC interacts with the CARD domain of NLRP3 via its own CARD domain, while simultaneously undergoing oligomerization to form "ASC specks" [4,5]. This structure further recruits and activates pro-caspase-1; the activated caspase-1 (cleaved caspase-1) then cleaves pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 to generate biologically active mature IL-1β and IL-18, ultimately initiating the inflammatory response [4]. During this process, the presence of ASC is an essential prerequisite for the NLRP3 inflammasome to complete the transition from assembly to functional execution. The absence of ASC means a critical break in this pathway. The intrinsic trait of RAW264.7 cells precisely blocks this critical step. Sufficient research has confirmed that RAW264.7 cells naturally do not express ASC protein due to epigenetic silencing mechanisms, primarily DNA methylation [6,7]. This characteristic is not an accidental result of experimental operational errors but a widely recognized molecular phenotype of this cell line. Authoritative data provided by reagent manufacturers further corroborate this: the product manual for the ASC antibody (catalog number #ab309499, the same antibody used in Zhao et al.’s study) from Abcam explicitly states that RAW264.7 cells should serve as a "negative control for ASC detection," and no ASC protein can be detected in their cell lysates. Additionally, Western blot results published on Abcam’s official website (Figure 2) show that a clear ASC band is detectable in J774A.1 cells (a fellow murine macrophage cell line, Lane 1), while no ASC signal is observed in RAW264.7 cells (Lane 2), further verifying the authenticity of ASC deficiency in RAW264.7 cells.

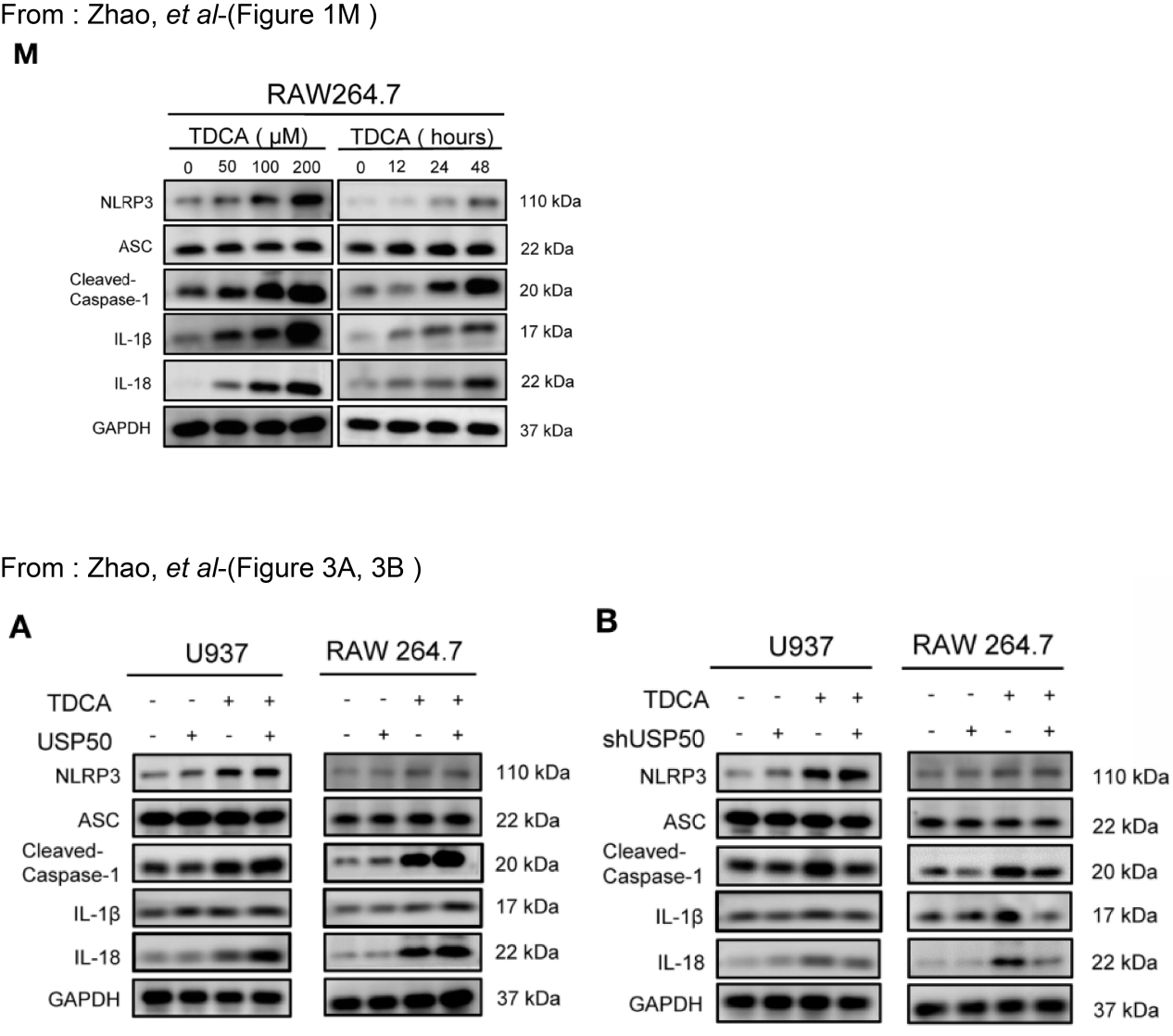

The core impact of this intrinsic deficiency on Zhao et al.’s study focuses on the mechanistic interpretation of "USP50-ASC interaction regulating the NLRP3 inflammasome" [1]. Zhao et al. proposed that "USP50 binds to ASC, removes its K63-linked ubiquitination modification, promotes ASC speck formation and oligomerization, and thereby activates the NLRP3 inflammasome." They supported this conclusion using in vitro experiments with RAW264.7 cells, such as Western blot detection of ASC expression and validation of USP50-ASC interaction (Figure 1). However, given the well-established ASC deficiency in RAW264.7 cells, the proposed mechanistic chain faces a fundamental inconsistency at its foundation: on one hand, this cell line cannot provide ASC—the substrate for USP50 action. Theoretically, it is impossible to observe the interaction between USP50 and ASC, let alone detect ASC speck formation or oligomerization; on the other hand, the absence of ASC directly leads to the failure of NLRP3 inflammasome assembly. Even if USP50 is normally expressed, it cannot activate caspase-1 or induce the release of mature IL-1β/IL-18. This is inconsistent with the results reported by Zhao et al., who stated the detection of "ASC protein and molecules related to NLRP3 inflammasome activation (such as cleaved caspase-1 and IL-1β) in RAW264.7 cells." Notably, this inconsistency is not confined to the validity of individual experimental results but also has a cascading effect on the reliability of all in vitro data in the original study.

Figure 1. USP50 regulates NLRP3 inflammasome activation in duodenogastric reflux-induced gastric tumorigenesis. Reproduced from Zhao et al. [1].

If the “ASC band” in RAW264.7 cells is confirmed as a false positive (e.g., via MS-based sequencing) a scenario strongly supported by ASC antibody cross-reactivity and RAW264.7’s established ASC deficiency—subsequent assays based on this cell line (specifically, assessments of USP50 knockdown/overexpression on NLRP3 inflammasome activation, such as cleaved caspase-1 and IL-1β release) lack a reliable experimental basis. This is because RAW264.7 cells cannot provide the endogenous ASC substrate required for canonical NLRP3 inflammasome activation, and the false-positive ASC signal undermines the interpretability of downstream inflammasome readouts. Notably, this uncertainty is specific to RAW264.7 cells; ASC ubiquitination assays in U937/293T cells (which express endogenous ASC) are not affected by this antibody cross-reactivity issue, as authentic ASC expression in these lines can be validated via orthogonal methods (e.g., MS or qPCR for ASC mRNA). This discrepancy in RAW264.7-based results does not negate the mechanistic data from U937/293T cells but highlights the need for clarification on RAW264.7 cell line status to ensure the overall consistency of the study’s conclusions. Moreover, this discrepancy could undermine confidence in the experimental design rigor of the study, as a comprehensive assessment of the RAW264.7 cell line’s molecular traits is essential before utilizing it in ASC-focused experiments. Insufficient consideration of its ASC-deficient trait may result in a mismatch between the experimental model and the research objectives, thereby reducing the interpretability of the results.

In fact, there are mature solutions to address the ASC deficiency in RAW264.7 cells and avoid such issues. Reagent companies such as InvivoGen have launched "RAW264.7 cell lines stably overexpressing ASC (RAW-ASC cells, catalog number raw-asc)." While retaining the macrophage properties of RAW264.7 cells, this cell line can provide functional ASC protein, making it a more suitable model for studying "ASC-dependent NLRP3 inflammasome activation." If Zhao et al.’s study had employed RAW-ASC cells rather than wild-type RAW264.7 cells, or included an "ASC-deficient control" within their experimental setup (e.g., simultaneous utilization of wild-type RAW264.7 and RAW-ASC cells to assess differences in NLRP3 inflammasome activation across the two cell lines), it would have effectively excluded interference arising from the "intrinsic cell line deficiency" and enhanced the credibility of their mechanistic reasoning. It is therefore advisable for the authors to employ short tandem repeat (STR) profiling, the gold standard for cell line identification, to verify the origin and purity of the cell lines. For cell lines with well-characterized molecular phenotypes (e.g., ASC deficiency in RAW264.7), targeted assays should be performed to confirm key traits, including Western blotting with validated antibodies (Figure 2) or qPCR for mRNA expression of lineage-specific markers, ensuring alignment between the cell line’s inherent properties and study objectives. Appropriate cell line trait-tailored positive/negative controls are essential; for ASC-dependent pathway studies, parallel experiments using ASC-expressing (e.g., J774A.1, RAW-ASC engineered cells) and ASC-deficient (wild-type RAW264.7) cell lines validate phenotypic specificity and exclude artifacts. In summary, cell line authentication and contamination checks are foundational to research integrity. Implementing these methods ensures experimental models accurately reflect intended molecular characteristics, safeguarding result reliability and mechanistic interpretation validity—particularly in lineage-specific signaling studies (e.g., NLRP3 inflammasome activation).

Figure 2. Western blot analysis of extracts from J774A.1 (Lane1) and RAW264.7 (Lane2) cells using ASC rabbit monoclonal antibody (ab309497) and GAPDH rabbit monoclonal antibody (ab181602). The data were downloaded from the website of Abcam company.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the intrinsic ASC deficiency in RAW264.7 cells is not merely a "detail of cell line characteristics" but a critical experimental background directly linked to the core mechanisms of NLRP3 inflammasome research. When using this cell line as a model for ASC-related inflammasome studies, it is first necessary to confirm whether the cells exhibit functional ASC expression. Alternatively, the impact of the deficiency can be avoided by using engineered cell lines (e.g., RAW-ASC) or adding negative controls.

For the published study by Zhao et al., resolving inconsistencies in RAW264.7-based ASC-related results requires a tiered approach of supplementary validation, integrating both protein-level and functional corrective experiments: (1) Protein-level validation: Use LC-MS/MS to confirm the identity of the “ASC band” and Pycard qPCR/promoter methylation analysis to verify ASC silencing—these will definitively rule out authentic ASC expression in RAW264.7 cells. (2) Functional validation: Repeat ASC-dependent inflammasome assays in ASC-positive models (J774A.1 cells or primary BMDMs) and RAW-ASC reconstituted lines, alongside USP50 rescue experiments with catalytically inactive mutants. These experiments will validate whether the USP50-ASC-NLRP3 axis is reproducible in physiologically relevant, ASC-competent models. Collectively, these corrective steps not only address the specific limitations of the original RAW264.7-based data but also provide a rigorous framework for validating ASC-related findings in future studies—ensuring that conclusions about inflammasome activation are anchored in both protein identity and functional causality. Only then can the conclusion that "USP50 regulates ASC-mediated NLRP3 inflammasome activation" be further consolidated, ensuring the scientific validity and reliability of the research findings. This case also provides a valuable reference for subsequent similar studies: the selection of in vitro experimental models should be closely aligned with research objectives and the inherent molecular characteristics of the cell line. Thorough preliminary research and rigorous experimental design are the foundations for ensuring the credibility of research results.

Author Contributions

JR-L Conceptualization, Writing–original draft, Writing-review & editing, Funding acquisition. JG: Writing–review & editing, Funding acquisition. FY-M: Writing–review & editing, Validation. AG-X: Conceptualization, Writing–review & editing, Validation. CG-L: Writing-original draft, Writing-review & editing, Validation, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition.

Funding

This work was supported by the grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.82305387; No.82404670), Shenzhen Nanshan District Health System Science and Technology Major Project Outstanding Youth Fund (No. NSZD2024035), and Shenzhen Science and Technology R&D Fund Basic Research Project (No. JCYJ20230807115813028, No. JCYJ20240813140505007). GuangDong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (No.2023A1515110466).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

2. Balasubramaniyam T, Ahn HB, Lim J, Basu A, Kubiak JZ, Rampogu S, et al. Therapeutic potential of polysaccharides in inflammation: current insights and future directions. Int Immunopharmacol. 2025 Dec 3;166:115538.

3. Watanabe N, Tamai R, Kiyoura Y. Alendronate augments lipid A‑induced IL‑1β release by ASC‑deficient RAW264 cells via AP‑1 activation. Exp Ther Med. 2023 Oct 26;26(6):577.

4. Nagar A, Bharadwaj R, Shaikh MOF, Roy A. What are NLRP3-ASC specks? an experimental progress of 22 years of inflammasome research. Front Immunol. 2023 Jul 26;14:1188864.

5. Proell M, Gerlic M, Mace PD, Reed JC, Riedl SJ. The CARD plays a critical role in ASC foci formation and inflammasome signalling. Biochem J. 2013 Feb 1;449(3):613–21.

6. Butts B, Gary RA, Dunbar SB, Butler J. Methylation of Apoptosis-Associated Speck-Like Protein With a Caspase Recruitment Domain and Outcomes in Heart Failure. J Card Fail. 2016 May;22(5):340–6.

7. Sun L, Ma W, Gao W, Xing Y, Chen L, Xia Z, et al. Propofol directly induces caspase-1-dependent macrophage pyroptosis through the NLRP3-ASC inflammasome. Cell Death Dis. 2019 Jul 17;10(8):542.