Abstract

Background: Primary angiitis of the central nervous system (PACNS) is a rare form of single-organ vasculitis, as classified by the 2012 Chapel Hill Consensus Conference. It affects small- and medium-sized vessels within the brain and spinal cord, arises independently of systemic disease, manifests with heterogeneous clinical features, and remains without definitive diagnostic biomarkers.

Objectives: This review aims to provide an updated overview of the literature on this complex condition, highlighting the diagnostic challenges it presents. Given its insidious onset and nonspecific clinical presentation, early recognition is crucial to prevent diagnostic delays and minimize the risk of irreversible neurological damage.

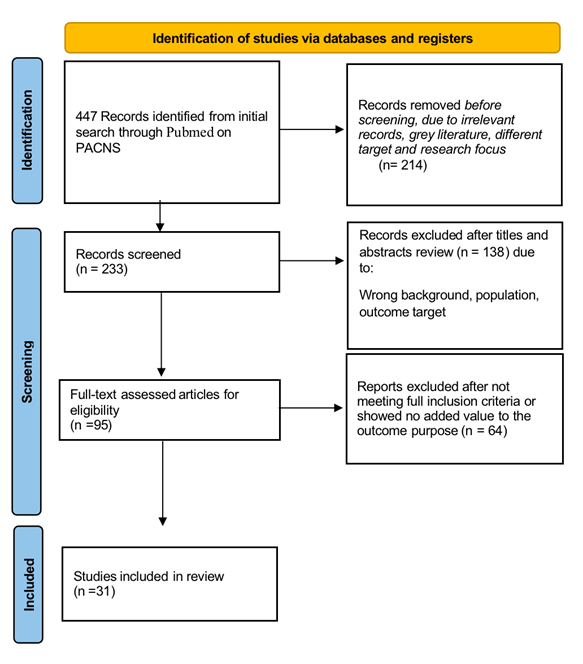

Methods: An online single-database search was done targeting literature published between 2000 and 2024. Only English-language articles focusing on clinical presentations and mimics in adult patients were included. Four manual screening stages were performed independently by two authors. Of 447 identified articles, 233 were selected after initial screening, and 95 underwent further review and were read in full. Ultimately, 31 articles were included in the final analysis. Data extraction included demographics, clinical presentation, misdiagnoses, cerebrospinal fluid and blood biomarkers, imaging findings, histopathological results, and reported epidemiologic or environmental risk factors.

Results: Across all populations, the most frequent clinical manifestations were stroke, headache, and seizures, in that order. Neurological deficits occurred in more than half of patients, often accompanied or preceded by headache. One study reported a higher prevalence of seizures in cases with small-vessel involvement. Cognitive impairment was observed but appeared less common compared with other vasculitis syndromes. Rare complications included unruptured intracranial aneurysms, pseudoaneurysms, and subcortical hemorrhage. No sex predilection was observed. PACNS was often misdiagnosed. Mimickers included systemic vasculitides, infectious vasculitides, vascular disorders, neoplastic conditions, and demyelinating diseases.

Conclusions: PACNS manifests with a broad clinical spectrum, most commonly stroke, headache, or seizures. Given its overlap with numerous mimicking conditions and its association with significant morbidity and mortality, a high index of suspicion and timely diagnosis are essential.

Keywords

Brain vasculitis, Primary CNS angiitis, Adult CNS vasculitis, Primary central nervous system vasculitis, Mimics, Clinical manifestations

Introduction

Vasculitides are a wide range of disorders characterized by inflammation and necrosis of blood vessels, which can lead to ischemia or vessel rupture and present as new neurological deficits or hemorrhages [1]. Therefore, vasculitis affecting the central nervous system results in significant morbidity and mortality [1]. Primary angiitis of the central nervous system refers to inflammation of the brain and spinal cord vessels, mainly impacting small- to medium-sized arteries but sometimes involving veins as well [1,2]. The cause of this disease is not well understood and is considered idiopathic, with an estimated incidence of about 2.4 cases per million person-years [2].

The terminology “PACNS” is preferred when describing vasculitis confined to the brain, spinal cord, and leptomeninges. According to the 2012 Chapel Hill Consensus Conference nomenclature, it is classified as a single-organ vasculitis [3]. The Calabrese and Mallek criteria remain the most widely applied diagnostic framework [4]; however, its nonspecific clinical manifestations and frequent misdiagnosis make isolated CNS angiitis particularly difficult to recognize [4,5].

This clinically heterogeneous condition frequently manifests with a progressive headache and a variable neurologic disability, often accompanied by cognitive impairment [2]. Diagnosis is typically delayed due to a gradual onset, the absence of specific biomarkers, and a considerable overlap with other conditions that mimic PACNS [2–5]. These include systemic vasculitides with CNS involvement, infections, and leukodystrophy. Mass lesions are frequently reported; hence a neoplastic disease must be ruled out [5]. Therefore, a careful and comprehensive exclusion of these other disorders is a crucial part of the diagnostic process.

Cerebral angiography and brain biopsy are essential for diagnosis, with biopsy being the gold standard after ruling out secondary causes [6]. Besides identifying CNS infections, CSF analysis reveals abnormalities in 80–95% of patients and helps exclude other diagnoses [6]. Improving diagnostic accuracy is crucial to prevent unnecessary and potentially harmful immunosuppressive treatment in patients with non-inflammatory conditions [7].

Because cases are rare, most available evidence comes from case series, case reports, and expert opinion rather than randomized controlled trials [1]. Limitations in applying diagnostic criteria and delays in treatment contribute to poor long-term outcomes of the disease [2].

Methods

Information sources and search strategy

A web-based literature search was performed manually using PubMed, for articles from 2000 to 2024. Keywords included “Brain vasculitis,” “primary CNS angiitis,” “adult CNS vasculitis,” “primary central nervous system vasculitis,” “mimics,” and “clinical manifestations.” The initial search yielded 447 articles, after removing irrelevant records, 233 articles were selected and underwent initial screening by reading the abstract. Ninety-five articles were read thoroughly, and 31 met the inclusion criteria for analysis. Two authors independently conducted all screening stages to ensure accurate results. The selection process followed PRISMA 2020 and is shown in Figure 1.

Data extraction

Relevant data were compiled into an Excel data extraction sheet. Data variables include the study citation and design, sample size, patient characteristics and gender, mimics misdiagnosed and reported, the onset of diagnosis, and presenting symptoms.

Eligibility criteria

We included only studies on PACNS in adults, regardless of diagnostic method (angiography or biopsy-proven) or patients’ medical history. Eligible designs included cohort studies, case-control studies, case series, case reports, and literature reviews.

Exclusion criteria

We excluded studies involving pregnancy, children, secondary CNS vasculitides, and those not focused on clinical manifestations, mimics, or differential diagnoses, as well as gray literature, abstracts, and studies lacking full-text access.

Outcomes of interest

The primary outcomes of interest were the clinical features and diagnostic challenges related to PACNS. We specifically focused on conditions that mimic PACNS, as these often result in misdiagnosis or delays.

Results

Results were grouped into 13 cohort studies and 18 case reports, with gender analysis limited to case reports. Outcomes were classified into three categories: (1) clinical presentations and onset of PACNS by time of diagnosis, (2) common mimickers leading to misdiagnosis and inappropriate treatment (Tables 1 and 2), and (3) other clinically relevant findings in cohort studies.

|

Secondary or systematic vasculitis |

|

Infections (eg. varicella zoster) |

|

Drug-induced vasculitis |

|

Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome |

|

Intracranial atherosclerotic disease |

|

Ischemic, Atherothrombotic or Cardioembolic stroke |

|

Susac’s Syndrome |

|

Autoimmune disease (eg. Anti-phospholipid antibody syndrome, systemic lupus erythematous, Neuro-sarcoidosis and neuro-Behcet’s disease) |

|

Multiple Sclerosis and MS-Spectrum Diseases |

|

Amyloid Beta-Related Angiitis |

|

Moyamoya Disease |

|

CNS lymphoma and Other Malignancy |

|

Sneddon’s Syndrome |

|

Cerebral Autosomal Dominant Arteriopathy and Leukoencephalopathy |

|

Category |

Strongest Biomarkers |

Notes |

|

CSF |

IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, NfL, pleocytosis, ↑protein |

Most reliable biological source |

|

Blood |

Endothelial markers (VEGF, sICAM-1), cytokines |

Low sensitivity |

|

Biopsy |

CD4? T-cell vasculitis, granulomas, amyloid-β |

Diagnostic gold standard |

|

Imaging |

Vessel wall MRI |

Non-invasive activity marker |

|

Emerging |

microRNA, cell-free DNA, TREM-2 |

Research level only |

Cohort Study Results

Clinical presentation and onset

In Salvarani et al. [8] and de Boysson et al. [9], headache was the most common initial symptom, followed by neurological deficits. In de Boysson et al. [9], headache was nearly universal at onset, often preceding neurological symptoms by days to weeks. Five patients with prior migraines described these headaches as “new” or atypical. Sheikh et al. [10] studied 5 patients and observed progressive holocephalic headaches and nonspecific cognitive changes in all of them.

Salvarani et al. [2] reported persistent neurological deficits and headache as the most common initial symptoms, occurring in 68% of patients. They noted that all patients had multiple manifestations at presentation, most frequently headache, altered cognition, focal neurological manifestations, persistent neurological deficits or stroke, and visual symptoms. Intracranial hemorrhage was infrequent. Stroke was also seen in 51% of patients in Paramasivan et al. [11]. Ruiz-Nieto et al. [12] identified focal neurological signs (visual, behavioral, or cognitive changes) at onset in four patients.

Agarwal et al. [13] found that seizures are the primary manifestation at diagnosis of PACNS, followed by headache; most patients experience worsening neurologic deficits. A study by Marrodan et al. [14] found seizures to be more common in PACNS, in comparison to Susac syndrome. Furthermore, Guo et al. [15] and de Boysson et al. [16] demonstrated that seizures are the most common presenting symptom. One of them (de Boysson et al., [16]) focused on small-vessel vasculitis and found that seizures are the leading manifestation, along with cognitive decline, impaired consciousness, and dyskinesias. In Salvarani et al. [17], which focused on unilateral relapsing primary PACNS, seizures were also identified as the most common presenting feature at diagnosis and during flares of PACNS.

Diagnosis was delayed in all studies, with timing varying by group; however, all reported a median time to diagnosis of 0.1 years. Agarwal et al. [13] showed an average of 23 months from onset to diagnosis. Ruiz-Nieto et al. [12] reported a median symptom duration of 36 weeks before diagnosis, with one case lasting over 3 years.

Mimickers

Misdiagnosis was common across cohorts. In all groups, the most frequent mimics were systemic vasculitides and infections, listed first among the differential diagnoses. Additionally, in Paramasivan et al. [11], the differential list included diseases that mimic similar angiographic appearances, such as reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome (RCVS) and intracranial atherosclerotic disease. In Becker et al. [18], out of 69 patients, only a subset were confirmed with PACNS, while 44 patients were ultimately diagnosed with 15 alternative conditions, with the most common being: secondary CNS vasculitis, Multiple sclerosis, Moyamoya disease, embolic stroke of unknown origin, atherothrombotic stroke, RCVS, and Susac syndrome.

Other relevant findings

Agarwal et al. [13] reported spinal cord involvement in 38.3% of patients, compared to 5% in Salvarani et al. [19]. Salvarani et al. [20] identified unruptured intracranial aneurysms in 12 patients (5.5%)—11 at diagnosis, one during follow-up. In Marrodan et al. [14], which aimed to distinguish Susac syndrome from PACNS, both conditions showed brain infarcts on MRI, which made diagnosis challenging without the complete Susac triad or specific angiographic features for PACNS.

Risk factors identified in literature

Across included cohort studies, no single definitive risk factor was consistently associated with the development of PACNS. However, several recurrent patterns emerged:

Age and sex trends: Most cases occurred in adults between their 30s and 60s, with a mild male predominance reported in some cohorts (Salvarani et al., [2]; de Boysson et al., [9]). These trends were not strong enough to establish clear epidemiologic risks but were consistent across studies.

Preceding or triggering events: A small number of reports described PACNS onset following viral infections, nonspecific inflammatory illnesses, or periods of heightened immune activation. These triggers were inconsistently reported and not universal, but they appeared across several cohorts.

Comorbid vascular risk factors: Conditions such as hypertension, smoking, and hyperlipidemia were described in some patients.

Overall, available evidence suggests limited identifiable risk factors, supporting the characterization of PACNS as a rare, sporadic, and largely idiopathic inflammatory vasculopathy.

Biomarkers associated with vascular inflammation in PACNS

Studies included in this review highlighted several biomarkers—laboratory, CSF, and imaging-based—that reflect vascular inflammation and assist in distinguishing PACNS from its mimics:

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) abnormalities: Most cohort studies (e.g., Salvarani et al., [2], de Boysson et al., [16]) reported mild lymphocytic pleocytosis and elevated protein as the most consistent CSF findings. These indicated intrathecal inflammation and blood–brain barrier disruption. CSF glucose was typically normal.

Inflammatory markers: Serum ESR and CRP were often normal or only mildly elevated and were not reliable indicators of CNS-restricted vasculitis. Their absence did not exclude PACNS, which helped distinguish PACNS from systemic vasculitides.

Immunologic and endothelial markers: Although not systematically reported across all cohorts, some studies referenced elevations in nonspecific markers of endothelial injury—such as von Willebrand factor (vWF) or cell-adhesion molecules—in PACNS patients. These findings were described as supportive rather than diagnostic.

Neuroimaging biomarkers: Multifocal infarcts of varying ages on MRI were consistently noted as characteristic but nonspecific. More recent studies referenced the diagnostic value of vessel-wall MRI, showing concentric vessel wall thickening and enhancement, which strengthened the suspicion for inflammatory vasculitis and helped differentiate PACNS from RCVS.

Overall, the studies included support the use of CSF analysis and vessel-wall imaging as key inflammatory biomarkers, although no specific laboratory biomarker currently establishes a definitive diagnosis.

To summarize the biomarkers reported across studies, Table 3 categorizes their source, reliability, and clinical relevance.

|

Recurrent brainstem encephalitis syndrome |

|

Ischemic stroke |

|

CNS malignancy (CNS lymphoma, glioma, astrocytoma, brain metastasis, and bilateral orbital tumors) |

|

Susac syndrome |

|

Diffuse leukoencephalopathy |

|

Non-Convulsive Status Epilepticus (NCSE) |

|

Autoimmune encephalitis |

|

Systemic vasculitis |

|

Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (EGPA) |

|

Non-compressive dorsal myelopathy |

|

Unusual brain abscess or tumefactive vasculitis. |

|

Multiple sclerosis |

Case Report Findings

A total of 18 case reports were included, encompassing 10 male and eight female patients.

Patient characteristics

Reported ages ranged from patients in their 20s to those in their 30s, 40s, 60s, and 80s. The gender distribution was balanced (10 males, eight females), with most presenting with subacute to chronic neurological manifestations that often resembled stroke. No specific risk factors or comorbidities were identified or linked to PACNS; although hypertension and smoking were common findings, most patients had no significant past medical history.

Presenting symptoms

In all case reports, headache, seizures, and neurological symptoms were the most common presentations. Stroke-like symptoms were prevalent in both genders. Deficits were recurring, transient, and non-specific, including aphasia, hemiparesis, paraparesis, blurred vision, and sometimes autonomic issues like bladder dysfunction. Dizziness, ataxia, and gait disturbances were also common findings. One case described two months of headache along with behavioral changes, ataxia, recent memory loss, recurrent convulsions, abducens palsy, and hemiparesis. Another case report, initially misdiagnosed as multiple sclerosis, documented a four-year history of dizziness, bladder dysfunction, and gradually worsening gait.

Mimickers

Alternative diagnoses were frequently considered before confirming PACNS, as shown in Table 3. Three studies reported misdiagnosis as ischemic stroke, including one with left MCA involvement and intracranial pseudoaneurysms on CT angiography. Six studies misdiagnosed CNS malignancy, with three as gliomas and the rest as brain metastasis, bilateral orbital tumors, and an astrocytoma. Pseudo-aneurysms and hemorrhagic cases were rare and observed in females. Additional reports included cases mimicking multiple sclerosis, inherited leukodystrophy, autoimmune encephalitis, Churg-Strauss syndrome, brain abscess, and non-compressive dorsal myelopathy.

Discussion

PACNS is rarely seen in clinical practice, making early identification and suspicion difficult. Although research and treatment options are advancing, progress in understanding its etiology and disease process remains slow. Brain biopsy is the definitive diagnostic method; however, angiography is often preferred by both patients and clinicians due to concerns about the invasiveness of biopsy and the risk of missing affected tissue [8,21].

The diagnostic criteria for PACNS were initially proposed by Calabrese and Mallek (1988) and included the following: (1) the presence of unexplained neurological deficits after thorough clinical and laboratory evaluation; (2) documentation by angiographic findings and/or pathology showing arteritis in the CNS; and (3) the absence of systemic vasculitis or other secondary conditions [22].

Our literature review revealed that clinical presentation is a critical factor in determining prognosis and outcomes. Because PACNS often mimics stroke or TIA, it is frequently treated conservatively, leading to recurrent symptoms until ischemic changes can no longer explain manifestations. Seizures are equally common but more challenging to investigate and are linked to specific PACNS subtypes. For instance, patients with small vessel or unilateral relapsing PACNS typically present with seizures, and they are less likely to have focal neurological deficits, unlike those with large- or medium-vessel PACNS [11,15,23].

Headache was reported in all cohorts and case reports, consistently affecting every patient and typically preceding other symptoms. It was always described as new and holocephalic, distinct from other headache types, including migraines, especially when accompanied by neurological symptoms or preceding seizures [9].

This research also aimed to identify conditions that resemble PACNS in the literature and to highlight similarities in disease features and presentations that may cause delayed recognition and treatment. Initial assessments usually focused on ruling out infections, drug-related causes, and systemic autoimmune diseases, as detailed in case reports. Comprehensive imaging, autoimmune testing, EEG, and lumbar puncture were routinely performed. Ultimately, only angiography and biopsy provided a definitive diagnosis. In some cases, diagnosis was made by exclusion when biopsy results were inconclusive or refused, and angiography was the only available option [9,11,15,21–24].

Systemic features such as weight loss, night sweats, and fever are uncommon in PACNS and should prompt evaluation for secondary CNS vasculitis. Remarkably, in one case from our research, a patient with low-grade fever, blurred vision, and headache was initially suspected of having a brain abscess, but biopsy confirmed a necrotic pattern of tumefactive PACNS [25].

Connective tissue diseases must be ruled out and investigated thoroughly, as CNS involvement is not uncommon with them, especially systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) is highly considered in the differential diagnosis of CNS vasculitis, as antibody-mediated damage targets seizures and cognitive dysfunction [26].

The differential diagnosis for suspected small-vessel vasculitis is specific and depends on the particular pattern of organ and tissue involvement. CNS involvement occurs in about 2–8% of patients with granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) and Churg-Strauss syndrome, and in 10–49% of those with Behcet’s disease, either due to primary CNS inflammation or venous-predominant vasculitis [27–29].

A study by Marrodan et al. sought to differentiate Susac syndrome from PACNS, emphasizing that cognitive impairment, cerebellar ataxia, and auditory disturbances are more frequent in Susac patients, while seizures were more common in PACNS. Susac’s syndrome is a microangiopathy of unclear pathophysiology, commonly seen in young adult females. Diagnosis requires the presence of at least two of the three components of its clinical triad, plus the presence of snowball lesions on brain MRI [14].

In contrast to PACNS, reversible cerebral vasoconstriction usually presents with a sudden, intense thunderclap headache. Its clinical severity can vary, often including hypertension and focal neurological deficits [30]. RCVS must be carefully considered, particularly because treatment involves calcium channel blockers rather than immunotherapy.

PACNS diagnostic criteria often overlap with the 2010 McDonald criteria for multiple sclerosis (MS), as PACNS can mimic clinical and radiological features of several neurological diseases, including MS and related disorders [31]. Microhemorrhages and persistent contrast-enhancing lesions despite treatment should prompt consideration of vasculitis in the differential diagnosis of multiple sclerosis.

Conclusion

Primary angiitis of the central nervous system (PACNS) can manifest in many different ways, making it a diagnostic challenge. Patients may present with stroke-like episodes, transient neurological deficits, seizures, persistent headaches, or progressive cognitive changes. In some forms of the disease, more specific features can appear. For instance, small-vessel involvement or the presence of pseudoaneurysms may predispose patients to seizures or even small microhemorrhages. The range of possible mimics is broad, but infections and autoimmune conditions are among the most common considerations. Because outcomes are closely tied to how quickly the disease is recognized and treated, maintaining a strong level of clinical suspicion is essential whenever PACNS is on the differential. Prompt recognition of PACNS can transform a potentially devastating disease into one with far more favorable outcomes.

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-assisted Technologies in the Manuscript Preparation Process

During the preparation of this work the author(s) used [Grammarly] in order to proofread the manuscript English language and grammar. After using this tool/service, the author(s) reviewed and edited the content as needed and take(s) full responsibility for the content of the published article.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

2. Salvarani C, Brown RD Jr, Calamia KT, Christianson TJ, Weigand SD, Miller DV, et al. Primary central nervous system vasculitis: analysis of 101 patients. Ann Neurol. 2007 Nov;62(5):442–51.

3. Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, Basu N, Cid MC, Ferrario F, et al. 2012 revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference Nomenclature of Vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum. 2013 Jan;65(1):1–11.

4. Boulouis G, de Boysson H, Zuber M, Guillevin L, Meary E, Costalat V, et al. Primary Angiitis of the Central Nervous System: Magnetic Resonance Imaging Spectrum of Parenchymal, Meningeal, and Vascular Lesions at Baseline. Stroke. 2017 May;48(5):1248–55.

5. Gianno F, Antonelli M, d'Amati A, Broggi G, Guerriero A, Erbetta A, et al. Primary angiitis of the central nervous system. Pathologica. 2024 Apr;116(2):134–9.

6. Byram K, Hajj-Ali RA, Calabrese L. CNS Vasculitis: an Approach to Differential Diagnosis and Management. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2018 May 30;20(7):37.

7. Kraemer M, Berlit P. Primary central nervous system vasculitis - An update on diagnosis, differential diagnosis and treatment. J Neurol Sci. 2021 May 15;424:117422.

8. Salvarani C, Brown RD Jr, Christianson TJ, Huston J 3rd, Giannini C, Miller DV, Hunder GG. Adult primary central nervous system vasculitis treatment and course: analysis of one hundred sixty-three patients. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015 Jun;67(6):1637-45.

9. de Boysson H, Zuber M, Naggara O, Neau JP, Gray F, Bousser MG, et al. Primary angiitis of the central nervous system: description of the first fifty-two adults enrolled in the French cohort of patients with primary vasculitis of the central nervous system. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014 May;66(5):1315–26.

10. Sheikh TS, Rozenberg A, Merhav G, Shifrin A, Stein P, Shelly S. Primary CNS vasculitis: insights into clinical, neuropathological, and neuroradiological characteristics. Front Neurol. 2024 Apr 8;15:1363985.

11. Paramasivan NK, Sharma DP, Mohan SMK, Sundaram S, Sreedharan SE, Sarma PS, et al. Primary Angiitis of the CNS: Differences in the Profile Between Subtypes and Outcomes From an Indian Cohort. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2024 Jul;11(4):e200262.

12. Ruiz-Nieto N, Aparicio-Collado H, Segura-Cerdá A, Barea-Moya L, Zahonero-Ferriz A, Campillo-Alpera MS, et al. Primary central nervous system vasculitis: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. A series of 7 patients. Neurología (English Edition). 2024 Jul 1;39(6):486-95.

13. Agarwal A, Sharma J, Srivastava MVP, Sharma MC, Bhatia R, Dash D, et al. Primary CNS vasculitis (PCNSV): a cohort study. Sci Rep. 2022 Aug 5;12(1):13494.

14. Marrodan M, Acosta JN, Alessandro L, Fernandez VC, Carnero Contentti E, Arakaki N, et al. Clinical and imaging features distinguishing Susac syndrome from primary angiitis of the central nervous system. J Neurol Sci. 2018 Dec 15;395:29–34.

15. Guo A, Zhang Z, Dong GH, Su L, Gao C, Zhang M, et al. Cortical Microhemorrhage Presentation of Small Vessel Primary Angiitis of the Central Nervous System. Ann Neurol. 2024 Jul;96(1):194–203.

16. de Boysson H, Boulouis G, Aouba A, Bienvenu B, Guillevin L, Zuber M, et al. Adult primary angiitis of the central nervous system: isolated small-vessel vasculitis represents distinct disease pattern. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2017 Mar 1;56(3):439–44.

17. Salvarani C, Hunder GG, Giannini C, Huston J 3rd, Brown RD. Unilateral Relapsing Primary CNS Vasculitis: Description of 3 Cases From a Single-Institutional Cohort of 216 Cases. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2023 Aug 2;10(5):e200142.

18. Becker J, Horn PA, Keyvani K, Metz I, Wegner C, Brück W, et al. Primary central nervous system vasculitis and its mimicking diseases - clinical features, outcome, comorbidities and diagnostic results - A case control study. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2017 May;156:48-54.

19. Salvarani C, Brown RD, Jr, Calamia KT, Christianson TJ, Huston J, 3rd, Meschia JF, et al. Primary CNS vasculitis with spinal cord involvement. Neurology. 2008;70:2394–400.

20. Salvarani C, Brown RD Jr, Christianson TJH, Huston J 3rd, Giannini C, Hunder GG. Primary central nervous system vasculitis with intracranial aneurysm. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2024 Oct;68:152506.

21. Campos AC, Sarmento S, Narciso M, Fonseca T. Primary Central Nervous System Vasculitis: A Rare Cause of Stroke. Cureus. 2023 May 26;15(5):e39541.

22. Calabrese LH, Mallek JA. Primary angiitis of the central nervous system. Report of 8 new cases, review of the literature, and proposal for diagnostic criteria. Medicine (Baltimore). 1988 Jan;67(1):20–39.

23. AbdelRazek MA, Hillis JM, Guo Y, Martinez-Lage M, Gholipour T, Sloane J, et al. Unilateral Relapsing Primary Angiitis of the CNS: An Entity Suggesting Differences in the Immune Response Between the Cerebral Hemispheres. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2021 Jan 5;8(2):e936.

24. Ireifej B, Kanevsky J, Song D, Almas T, Alsubai AK, Hadeed S, et al. Close, but no cigar: an unfortunate case of primary angiitis of the central nervous system. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2023 Feb 17;85(2):184–6.

25. Hajj-Ali RA, Calabrese LH. Central nervous system vasculitis: advances in diagnosis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2020 Jan;32(1):41–6.

26. Hajj-Ali RA, Calabrese LH. Central nervous system vasculitis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2009 Jan;21(1):10–8.

27. Nishino H, Rubino FA, DeRemee RA, Swanson JW, Parisi JE. Neurological involvement in Wegener's granulomatosis: an analysis of 324 consecutive patients at the Mayo Clinic. Ann Neurol. 1993 Jan;33(1):4–9.

28. Akman-Demir G, Serdaroglu P, Tasçi B. Clinical patterns of neurological involvement in Behçet's disease: evaluation of 200 patients. The Neuro-Behçet Study Group. Brain. 1999 Nov;122 ( Pt 11):2171–82.

29. Al-Araji A, Sharquie K, Al-Rawi Z. Prevalence and patterns of neurological involvement in Behcet's disease: a prospective study from Iraq. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003 May;74(5):608-13.

30. Cappelen-Smith C, Calic Z, Cordato D. Reversible Cerebral Vasoconstriction Syndrome: Recognition and Treatment. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2017 Jun;19(6):21.

31. de Souza Tieppo EM, da Silva TFF, de Araujo RS, Silva GD, Paes VR, de Medeiros Rimkus C, et al. Primary angiitis of the central nervous system as a mimic of multiple sclerosis: A case report. J Neuroimmunol. 2022 Dec 15;373:577991.