Abstract

Background & Aim: Patients presenting with an array of benign oral mucosal diseases to oral & maxillofacial (OMF) units practicing risk habits such as betel chewing could be at high risk of poor oral health and progressing into Oral Potentially Malignant Disorders (OPMD) or oral cancer. Against this backdrop, we investigated the possible role of selected habits, periodontal disease an oral hygiene in occurrence and prognosis of oral mucosal lesions, among a cohort of patients in Sri Lanka.

Material & Methods: The study included newly diagnosed patients aged >18-years presented with benign oral mucosal diseases. The sample comprised of 134 patients. The data were collected by a pre-tested validated interviewer-administered questionnaire which comprised of socio-demographic information, information on risk habits and data on clinical oral examination for oral hygiene and periodontal disease status.

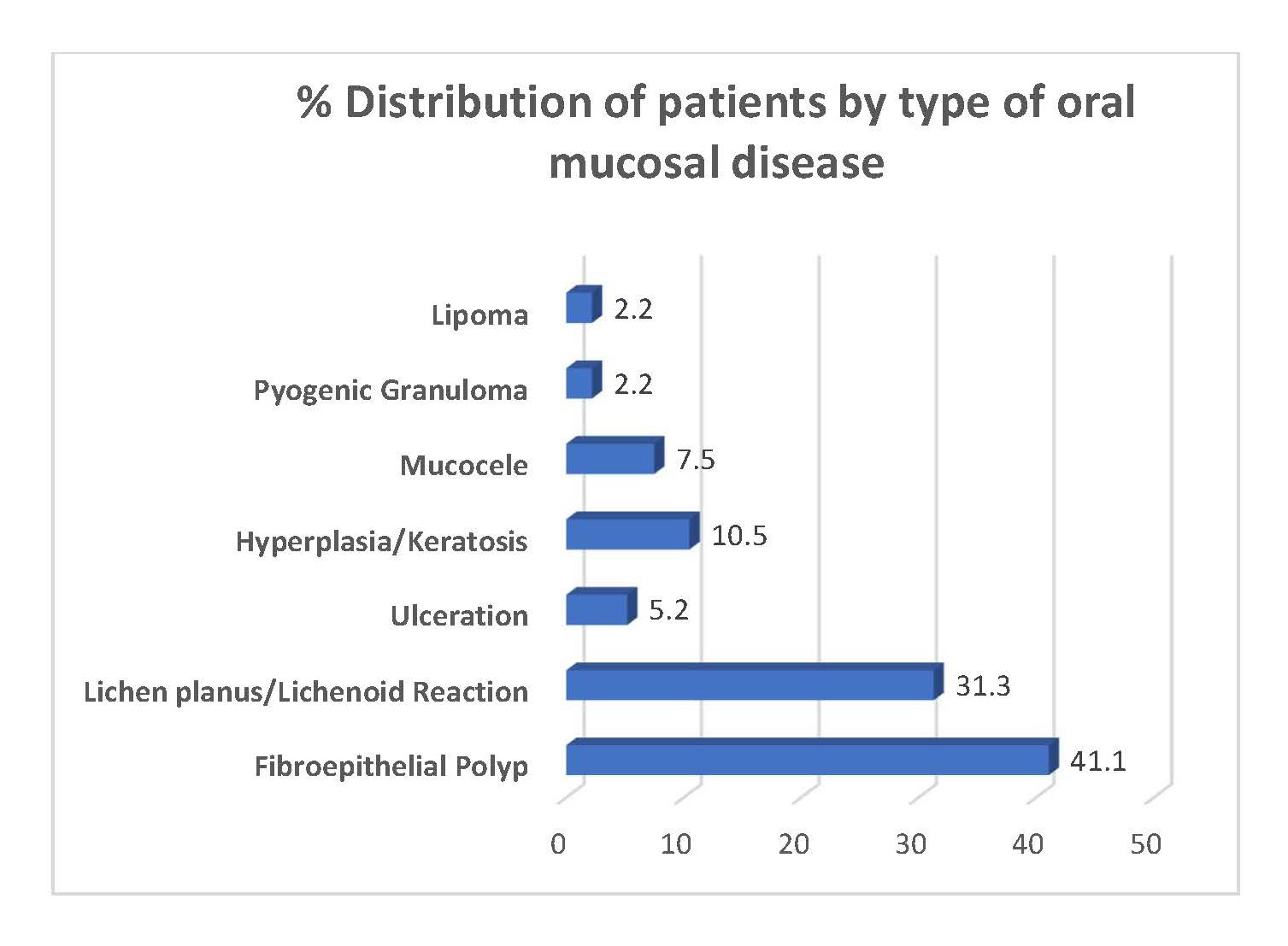

Results: Descriptive statistics and Chi-Square test of statistical significance were used. The leading mucosal condition was fibro epithelial polyp (41.1%) followed by lichenoid reaction (31.3%). Majority attained General Certificate of Education- Advanced level and ordinary levels education (33.6% and 30.6%) respectively. By occupational status, there was a variation ranging from skilled and unskilled laborer’s (35.1%) to 23.1% of professionals. Moreover, 26.9% of patients were chewing betel on a daily basis while another 14.2% at certain times. Frequency of betel chewing was significantly associated with male gender, moderate to poor oral hygiene, moderate to severe periodontal disease status (p=0.001). Whilst levels of education and occupational status were significantly associated with above conditions (p<0.05).

Conclusions: Present findings provided new insights into the unharnessed potential of patients presented to OMF units with benign oral mucosal diseases for primordial and primary prevention and control of OPMD and oral cancer.

Keywords

Benign oral mucosal disease, Betel chewing, Risk habits, Oral hygiene, Periodontal disease, Sri Lanka

Introduction

Patients with an array of benign oral mucosal diseases comprising fibro-epithelial polyps, lipomas and lichen planus commonly present to Oral & Maxillofacial units. While managing their specific conditions, it is important to assess for their risk habits such as betel chewing which is associated with a high burden of periodontal disease as evident from research findings [1-3]. Moreover, recent research has found the association of periodontal disease with increased risk for an array of cancers [4-6]. In addition, several systematic reviews and some research articles as well have suggested periodontal disease as an independent emerging risk marker for oral cancer [7-9], however could be attenuated when adjusted for major confounding factors such as smoked and smokeless tobacco and alcohol use [7].

Betel chewing with or without tobacco is related to oropharyngeal cancers and its preceding condition, oral potentially malignant disorders (OPMD) as a dominant etiological and risk factor [10,11]. This relationship has garnered interest among many researchers across the globe from public health perspectives through to molecular perspectives [10]. Betel chewing is a lifestyle- related risk factor deeply ingrained into the sociocultural fabric of many Asia-Pacific countries since antiquity [11,12] thereby gaining recognition of betel quid as a socially endorsed masticatory product [8]. Recent research evidence demonstrates several mechanisms of carcinogenesis associated with betel quid and its ingredients such as tobacco, areca nut and slaked lime. For example, tobacco and areca nut specific carcinogens such as nitrosamine, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, metals and metalloids, aldehydes and a consortium of co-carcinogens have been reported [13-15]. Furthermore, the prominent contribution of carcinogenic ingredients of betel quid on down regulation of antioxidant proteins and induction of reactive oxygen species influenced by oncogenes, epigenetics and immune modulation has been well appraised [16-18]. The dose-response relationship between betel chewing and increased risk for OPMD and oral cancer augmented by the duration of practice has also been established [19-21]. Moreover, this habit has been linked to an array of oral mucosal diseases ranging from chewer’s mucosa to OPMD, high burden of periodontal disease and poor oral hygiene [22-24]. In addition, there is research evidence to suggest that the betel chewing was related to metabolic syndrome, the precursor condition for many non-communicable diseases [25,26].

The oral cavity harbors the second most diverse microbial community in the body with over 700 bacterial species [23]. Poor oral hygiene status is an established risk factor for periodontal disease, one of the most common oral diseases which demonstrate polymicrobial synergism [27]. Therefore, recent research evidence suggests the possibility of dysbiosis of oral microbiome induced by risk habits such as betel chewing and its possible association with initiation and progression of oral carcinogenesis [23]. Interestingly, recent molecular microbiological studies revealed that betel chewing contributed to significant alterations in the oral flora with increased proportions of periodontal pathogens such as Actinomyces, Tannerella, and Prevotella compared to non-chewers [25]. On the contrary, there is wealth of evidence for beneficial protective effects of daily fruit and vegetable consumption for an array of cancers including oral cancer [28-30]. However, there is research evidence to support low levels of daily fruit and vegetable consumption among high-risk groups for OPMD and oral cancer in developing countries [31,32].

Sri Lanka is a lower-middle-income-developing country with 21.67 million population and US$ 3,991 per capital income [33]. The most recently published Sri Lankan cancer incidence data reported 2,199 incidence oral cancer cases for the year 2014 [34]. Lip, tongue and mouth cancer was the leading cancer type among men, accounting for 15.7% of all cancers and ranked 8th among women representing 4% of all cancer sites for women [34]. Therefore, any attempt to reduce the burden of oral cancer and OPMD should harness the potential of primordial and primary preventive strategies and opportunities.

Patients seeking health care with benign oral mucosal diseases could be at high risk of progressing into OPMD or oral cancer especially if they practice harmful risk habits such as betel chewing. Against this backdrop, present study aims to investigate the pattern of oral mucosal disease, selected habits and related factors among a cohort of patients in Sri Lanka. Additionally, we explore the possible role of selected habits, periodontal disease an oral hygiene in occurrence and prognosis of oral mucosal lesions, among a cohort of patients in Sri Lanka.

Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional descriptive study was conducted among patients aged >18-years presented with benign oral mucosal diseases. The newly diagnosed patients were included while those who were already on treatment were excluded from the study. The study setting was Oral & Maxillo-Facial Unit D, Dental Institute, Colombo currently upgraded to National Dental Hospital (Teaching) Sri Lanka, the premier, multispecialty public dental hospital in Sri Lanka.

Non-random consecutive sampling technique was used to select participants and present investigation was based on 134 patients. Sample size calculation was done using formula stipulated by Lwanga & Lemeshow, 1991 [35] with absolute precision of 5% and 90% prevalence of moderate to poor oral hygiene among patients with oral mucosal lesions based on a pilot study conducted elsewhere. The calculated sample size was 138, however, due to incomplete data 4 were excluded. The inclusion criteria were age ≥ 18-years diagnosed with oral mucosal lesions whilst those who had oral cancers and oral potentially malignant disorders were excluded. As recruitment of participants were done on outpatient clinic days there could have been possible selection bias and as the data on habits were collected based on self-reports of respondents there could be possible recall bias. However, measures were taken to control for biases and confounders by adherence to study protocol. The conditions were diagnosed clinically and histopathologically as needed. The data were collected by a pre-tested validated interviewer-administered questionnaire used for a previous study [36] which comprised of socio-demographic data, information on risk habits and data on clinical oral examination. Oral hygiene status was assessed by Simplified Oral Hygiene Index (OHI-S) of Green & Vermillion, 1964 [37]. Periodontal disease status was assessed by the Centre for Disease Control (CDC) Periodontal Disease Surveillance Workgroup [38] which involved assessment of bleeding on probing (BOP), periodontal pocket depth (PPD), and clinical attachment loss (CAL) at four sites per anterior tooth and six sites per posterior tooth. Oral hygiene status was categorized as good, moderate and poor while periodontal disease status was categorized as no/mild, moderate and severe.

Data were entered and analyzed using SPSS-21 statistical software package. Descriptive statistics and chi-square test of statistical significance for group comparisons were employed for data analysis. Informed consent was obtained from participating patients. The ethics approval for the study was obtained from Sri Lanka Medical Association (ERC-15008).

Results

As shown in Figure 1, the leading type was fibro-epithelial polyps followed by lichen planus/lichenoid reactions.

Figure 1. Distribution of patients by type of oral mucosal disease.

As shown in Table 1, the majority 50.7% patients were aged 40-59 years while there were 61.2% of males. Majority of patients had attained an educational attainment of G.C.E. Advanced level and Ordinary levels (33.6% and 30.6% respectively). By occupational status, the majority were skilled and unskilled laborers (35.1%) and there was 23.1% of professionals. However, the sample comprised of 34.3% housewives who were females not in formal employment.

| Attribute | Number | % |

| Age group | ||

| 19-39 years | 40 | 29.9 |

| 40-59 years | 68 | 50.7 |

| 60-85 years | 26 | 19.4 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 82 | 61.2 |

| Female | 52 | 38.8 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Sinhalese | 119 | 88.8 |

| Tamil | 7 | 5.2 |

| Muslim | 8 | 6.0 |

| Level of Education | ||

| Primary Education | 13 | 9.7 |

| Secondary Education | 12 | 9.0 |

| G.C.E. (Ordinary Level) | 41 | 30.6 |

| G.C.E. (Advanced Level) | 45 | 33.6 |

| Degree/Diploma | 4 | 3.0 |

| Employment status | ||

| Farmers | 10 | 7.5 |

| Skilled & unskilled laborer’s | 47 | 35.1 |

| House wives | 46 | 34.3 |

| Professionals | 31 | 23.1 |

| Total | 134 | 100.0 |

As shown in Table 2, majority of patients reported betel chewing and daily consumption of vegetables.

| Habit | Number | % |

| Betel chewing | ||

| Never | 74 | 55.2 |

| One year back | 5 | 3.7 |

| Sometimes | 19 | 14.2 |

| Daily | 36 | 26.9 |

| Daily consumption of vegetables | ||

| No | 21 | 15.7 |

| Yes | 113 | 84.3 |

| Daily consumption of fruits | ||

| No | 69 | 51.5 |

| Yes | 65 | 45.5 |

| Total | 134 | 100.0 |

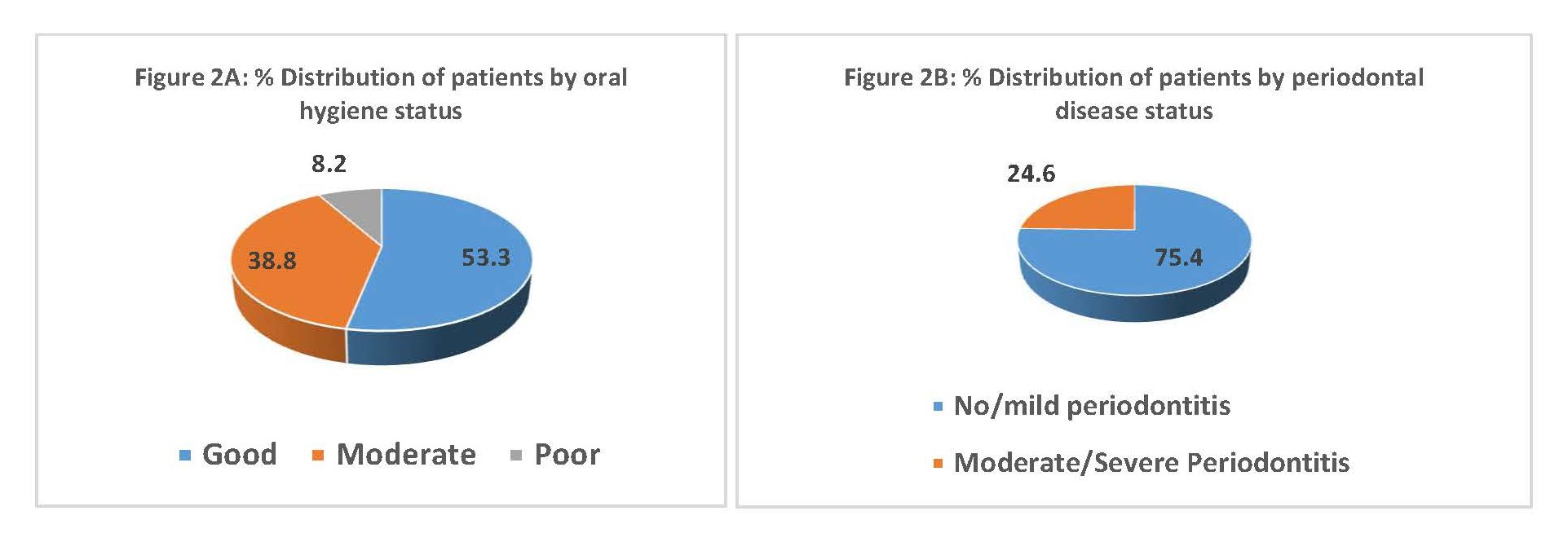

As illustrated in Figure 2A & B, the majority of patients had moderate to poor oral hygiene status and moderate to servere periodontitis.

Figure 2. % Distributions of patients by oral hygiene status (A) and periodontal disease status (B).

Table 3 demonstrates the association of sociodemographic characteristics, plaque levels and periodontal disease status by the frequency of betel chewing habits among patients. Accordingly, higher proportions of one year back and daily betel chewers had moderate to poor oral hygiene status (80.0% and 66.7% respectively) compared to never betel chewers (27.0%). Furthermore, same pattern was evident with periodontal disease burden with more daily betel chewers (45.5%) having moderate to severe periodontal disease compared to never betel chewers (13.2%) and those differences were statistical highly significant (p=0.0001).

| Attribute | Frequency of betel chewing habit | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never | One year back | Sometimes | Daily | p-value* | |

| N % | N % | N % | N % | ||

| Age group | |||||

| 18-39 years | 25 (62.5) | 0(0.0) | 6 (15.0) | 9 (22.5) | |

| 40-59 years | 37 (54.4) | 4 (5.9) | 9 (13.2) | 18 (26.5) | |

| 60-85 years | 12 (46.2) | 1 (3.8) | 4 (15.4) | 9 (34.6) | 0.680 |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 34 (41.5) | 5 (6.1) | 12 (14.6) | 31(37.8) | |

| Female | 40 (76.9) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (13.5) | 5 (9.6) | 0.001 |

| Educational Attainment | |||||

| Up to G.C.E O/L | 50 (50.5) | 3 (3.0) | 16 (16.2) | 30 (30.3) | |

| Above G.C.E. A/L | 24 (68.6) | 2 (5.7) | 3 (8.6) | 6 (17.1) | 0.172 |

| Oral Hygiene Status | |||||

| Mild | 51 (73.0) | 1 (20.0) | 7 (36.8) | 12 (33.3) | |

| Moderate to poor | 23 (27.0) | 4 (80.0) | 12 (64.2) | 24 (66.7) | 0.001 |

| Periodontal Disease Status | |||||

| Mild | 65 (87.8) | 3 (60.0) | 13 (68.4) | 20 (55.5) | |

| Moderate to severe | 9 (13.2) | 2 (40.0) | 6 (32.6) | 16 (45.5) | 0.001 |

| *Fisher’s exact test | |||||

As shown Table 4, a higher proportion of patients with lower level of education significantly presented with moderate to poor oral hygiene and periodontal disease status compared to their better educated counterpart. Similarly, those with better occupational status demonstrated significantly better oral hygiene and periodontal status than their counterpart with lower occupational status.

| Socio-demographic attribute | Oral Hygiene Status | p-value | Periodontal Disease Status | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acceptable | Moderate & poor | Mild | Moderate & severe | |||

| N % | N % | N % | N % | |||

| Level of Education | ||||||

| Up to GCE (Ordinary Level) | 47 (47.5) | 52 (53.5) | 69 (69.7) | 30 (30.3) | ||

| Above GCE (Advanced Level) | 24 (68.6) | 11 (32.4) | 0.03 | 32 (91.4) | 3 (8.6) | 0.01 |

| Occupation | ||||||

| Farmer | 1 (10.0) | 9 (90.0) | 3 (30.0) | 7 (70.0) | ||

| Skilled/unskilled/ house wife | 49 (52.7) | 44 (47.3) | 69 (74.2) | 24 (23.8) | ||

| Professional | 21 (67.7) | 10 (32.3) | 0.006 | 29(93.5) | 2 (6.5) | 0.001 |

Discussion

Patients presented with benign oral mucosal diseases to health care facilities provide a window of opportunity for improving their oral health status. Patients with oral mucosal lesions could be at elevated risk of getting OPMD and oral cancer especially if they practiced frequent betel chewing habit. This notion was further supported by the highly significant association of male gender with frequency of betel chewing. Moreover, as there was presentation of younger adults the findings indicated an opportunity to harness the potential to introduce primordial and primary preventive strategies in getting into the habit of betel chewing with or without tobacco.

The oral hygiene status and periodontal disease status of patients presented with benign oral mucosal diseases needs exploration for possible intervention. The literature on prevalence of oral mucosal diseases among different population groups with varying age and gender distribution as well as heterogenous mucosal conditions [39,40]. In the current sample the most prevalent oral mucosal condition was fibro epithelial polyp (41.1%), however, among Lebanese population it was hairy tongue (17.4%) [39] whereas Fordyce granules (3.8%) [40] among Saudi patients with wider age variation ranging from 15- 73 years thus comparable to current study findings. The differences in life-style related risk habits, dietary habits and socio-cultural differences in population groups could influence varying oral mucosal lesions that occur in them. Furthermore, in the current sample 41.1% were betel chewers and 31.3% of patients presented with lichenoid lesions as studies have reported an association between betel chewing and lichenoid lesions which is a betelquid associated oral mucosal disease [22]. However, its prevalence was 10.4% among a cohort of Indian betel chewers which was much lower compared to present study [41]. Moreover, authors of a review that described the clinical and pathological aspects of oral lichenoid contact lesions caused by areca nut and betel quid, stated that this condition garnered limited attention in the published literature [42]. Therefore, it is timely to conduct more research on betel quid associated lichenoid reaction among different populations.

As frequent betel chewing contributes to poor oral health status and periodontal disease status, intervening on such risk habits contribute to beneficial effects. Improving oral hygiene of patients presenting to Oral & Maxillofacial (OMF) units had not garnered recognition as a priority despite voluminous evidence on its association with increased risk of oral cancer [27]. A previous study reported the poor oral hygiene status and high periodontal disease burden of male oral cancer patients in Sri Lanka and the significant association of frequent betel chewing with the above [36]. Hence, current findings on a cohort of Sri Lankan patients with benign oral mucosal diseases corroborated the findings of that study.

It has been recommended to include interventions to improve oral hygiene and periodontal disease of oral cancer patients as well as reducing their risk habits taken their levels of education into consideration in standard management protocols [36]. In contrast to findings among male oral cancer patients [36], age and educational attainment were not significantly associated with betel chewing habit among benign oral mucosal disease patients. This could be plausibly attributed to sociodemographic differences among two groups as oral cancer patients were dominated by older ages and low levels of educational attainment compared to oral mucosal disease patients. The latter group was dominated by younger age groups who had a higher level of educational attainment [36]. Therefore, such a demographic profile provided an opportunity to harness for interventions on risk habit reduction and enhancing healthy habits. In addition, improving the diets of those patients with a variety of fruits in addition to vegetables they consumed could have beneficial effects on them [43]. Despite the younger age groups, higher levels of education and occupational status, the fair proportion of oral mucosal disease patients demonstrated moderate to poor oral hygiene in the present study. Moreover, as little over quarter of patients had moderate to severe periodontitis the findings indicated the need for improving the periodontal health status of those patients. Not surprisingly lower level of education and occupational status were significantly associated with moderate to poor oral hygiene status and periodontal disease status among the current sample. Low levels of education and occupational status negatively impact on hygiene practices due to poor knowledge, attitudes and economic constraints [44]. Recent research evidence suggested the importance of oral hygiene for betel chewers to control bacterial pathogen related oral diseases such as periodontitis [45].

Findings of the present study should be interpreted cautiously due to small sample size and less vigorous statistical models used. Therefore, further research warranted with larger sample sizes and rigorous multivariate analyses.

In conclusion, present findings suggest the need for standard management protocols for patients with oral mucosal lesions embracing interventions to improve their oral hygiene and periodontal disease with risk habit intervention.

References

2. Hsiao CN, Ting CC, Shieh TY, Ko EC. Relationship between betel quid chewing and radiographic alveolar bone loss among Taiwanese aboriginals: a retrospective study. BMC Oral Health. 2014 Dec;14(1):1-7.

3. Wellapuli N, Ekanayake L. Risk factors for chronic periodontitis in Sri Lankan adults: a population based case– control study. BMC Research Notes. 2017 Dec;10(1):1-7.

4. Shafique K, Zafar M, Ahmed Z, Khan NA, Mughal MA, Imtiaz F. Areca nut chewing and metabolic syndrome: evidence of a harmful relationship. Nutrition Journal. 2013 Dec;12(1):1-6.

5. Sharan RN, Mehrotra R, Choudhury Y, Asotra K. Association of betel nut with carcinogenesis: revisit with a clinical perspective. PLOS One. 2012 Aug 13;7(8):e42759.

6. Amarasinghe HK, Usgodaarachchi US, Johnson NW, Lalloo R, Warnakulasuriya S. Betel-quid chewing with or without tobacco is a major risk factor for oral potentially malignant disorders in Sri Lanka: a case-control study. Oral Oncology. 2010 Apr 1;46(4):297-301.

7. Javed F, Warnakulasuriya S. Is there a relationship between periodontal disease and oral cancer? A systematic review of currently available evidence. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 2016 Jan 1;97:197-205.

8. Corbella S, Veronesi P, Galimberti V, Weinstein R, Del Fabbro M, Francetti L. Is periodontitis a risk indicator for cancer? A meta-analysis. PLOS One. 2018 Apr 17;13(4):e0195683.

9. Javed F, Warnakulasuriya S. Is there a relationship between periodontal disease and oral cancer? A systematic review of currently available evidence. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 2016 Jan 1;97:197-205.

10. Xiao L, Zhang Q, Peng Y, Wang D, Liu Y. The effect of periodontal bacteria infection on incidence and prognosis of cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. 2020 Apr;99(15).

11. Wen BW, Tsai CS, Lin CL, Chang YJ, Lee CF, Hsu CH, et al. Cancer risk among gingivitis and periodontitis patients: a nationwide cohort study. QJM: An International Journal of Medicine. 2014 Apr 1;107(4):283-90.

12. Sharan RN, Mehrotra R, Choudhury Y, Asotra K.Association of betel nut with carcinogenesis: revisit with a clinical perspective. PloS one. 2012 Aug 13;7(8):e42759.

13. Corbella S, Veronesi P, Galimberti V, Weinstein R, Del Fabbro M, Francetti L. Is periodontitis a risk indicator for cancer? A meta-analysis. PLOS One. 2018 Apr 17;13(4):e0195683.

14. Gupta B, Johnson NW. Systematic review and meta-analysis of association of smokeless tobacco and of betel quid without tobacco with incidence of oral cancer in South Asia and the Pacific. PLOS One. 2014 Nov 20;9(11):e113385.

15. Faouzi M, Neupane RP, Yang J, Williams P, Penner R. Areca nut extracts mobilize calcium and release proinflammatory cytokines from various immune cells. Scientific Reports. 2018 Jan 18;8(1):1-3.

16. Islam S, Muthumala M, Matsuoka H, Uehara O, Kuramitsu Y, Chiba I, et al. How each component of betel quid is involved in oral carcinogenesis: mutual interactions and synergistic effects with other carcinogens—a review article. Current Oncology Reports. 2019 Jun;21(6):1-3.

17. Yang CM, Hou YY, Chiu YT, Chen HC, Chu ST, Chi CC, et al. Interaction between tumour necrosis factor-a gene polymorphisms and substance use on risk of betel quidrelated oral and pharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma in Taiwan. Archives of Oral Biology. 2011 Oct 1;56(10):1162- 9.

18. Tsai YS, Lee KW, Huang JL, Liu YS, Juo SH, Kuo WR, et al. Arecoline, a major alkaloid of areca nut, inhibits p53, represses DNA repair, and triggers DNA damage response in human epithelial cells. Toxicology. 2008 Jul 30;249(2- 3):230-7.

19. Yen AM, Chen SC, Chang SH, Chen TH. The effect of betel quid and cigarette on multistate progression of oral pre-malignancy. Journal of Oral Pathology & Medicine. 2008 Aug;37(7):417-22.

20. Madathil SA, Rousseau MC, Wynant W, Schlecht NF, Netuveli G, Franco EL, et al. Nonlinear association between betel quid chewing and oral cancer: Implications for prevention. Oral Oncology. 2016 Sep 1;60:25-31.

21. Amarasinghe AA, Usgodaarachchi US, Johnson NW, Warnakulasuriya S. High prevalence of lifestyle factors attributable for oral cancer, and of oral potentially malignant disorders in rural Sri Lanka. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention: APJCP. 2018;19(9):2485.

22. Tejasvi MA, Anulekha CK, Afroze MM, Shenai KP, Chatra L, Bhayya H. A correlation between oral mucosal lesions and various quid-chewing habit patterns: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Cancer Research and Therapeutics. 2019 Jul 1;15(3):620-24.

23. Perera M, Al-Hebshi NN, Speicher DJ, Perera I, Johnson NW. Emerging role of bacteria in oral carcinogenesis: a review with special reference to periopathogenic bacteria. Journal of Oral Microbiology. 2016 Jan 1;8(1):32762.

24. Uehara O, Hiraki D, Kuramitsu Y, Matsuoka H, Takai R, Fujita M, et al. Alteration of oral flora in betel quid chewers in Sri Lanka. Journal of Microbiology, Immunology and Infection. 2020 Jun 27.

25. Lertpimonchai A, Rattanasiri S, Vallibhakara SA, Attia J, Thakkinstian A. The association between oral hygiene and periodontitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International Dental Journal. 2017 Dec 1;67(6):332-43.

26. Börnigen D, Ren B, Pickard R, Li J, Ozer E, Hartmann EM, et al. Alterations in oral bacterial communities are associated with risk factors for oral and oropharyngeal cancer. Scientific Reports. 2017 Dec 15;7(1):1-3.

27. Gupta B, Kumar N, Johnson NW. Periodontitis, oral hygiene habits, and risk of upper aerodigestive tract cancers: a case-control study in Maharashtra, India. Oral Surgery, oral Medicine, Oral Pathology and Oral Radiology. 2020 Apr 1;129(4):339-46.

28. Dreher ML. Whole fruits and fruit fiber emerging health effects. Nutrients. 2018 Dec;10(12):1833.

29. Schwingshackl L, Schwedhelm C, Galbete C, Hoffmann G. Adherence to Mediterranean diet and risk of cancer: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients. 2017 Oct;9(10):1063.

30. Pavia M, Pileggi C, Nobile CG, Angelillo IF. Association between fruit and vegetable consumption and oral cancer: a meta-analysis of observational studies. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2006 May 1;83(5):1126-34.

31. Amarasinghe HK, Usgodaarachchi U, Kumaraarachchi M, Johnson NW, Warnakulasuriya S. Diet and risk of oral potentially malignant disorders in rural Sri Lanka. Journal of oral pathology & medicine. 2013 Oct;42(9):656-62.

32. Bravi F, Bosetti C, Filomeno M, Levi F, Garavello W, Galimberti S, et al. Foods, nutrients and the risk of oral and pharyngeal cancer. British Journal of Cancer. 2013 Nov;109(11):2904-10.

33. Economic and Social of Sri Lanka 2019. Central Bank of Sri Lanka. Central Bank of Sri Lanka. Volume XLI. Colombo. Sri Lanka http://cbsl.gov.lk.

34. Cancer incidence data Sri Lanka 2014, National Cancer Control Programme, Colombo, Sri Lanka. http://www.nccp.health.gov.lk/images/PDF_PUBLICATIONS/ Cancer_Incidence_in_Sri_Lanka_2014.pdf

35. Lwanga SK, Lemeshow S, World Health Organization. Sample size determination in health studies: a practical manual. World Health Organization; 1991.

36. Perera IR, Attygalla M, Jayasuriya N, Dias DK, Perera ML. Oral hygiene and periodontal disease in male patients with oral cancer. British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2018 Nov 1;56(9):901-3.

37. Greene JG, Vermillion JR. The simplified oral hygiene index. The Journal of the American Dental Association. 1964 Jan 1;68(1):7-13.

38. Page RC, Eke PI. Case definitions for use in population-based surveillance of periodontitis. Journal of Periodontology. 2007 Jul;78:1387-99.

39. El Toum S, Cassia A, Bouchi N, Kassab I. Prevalence and distribution of oral mucosal lesions by sex and age categories: A retrospective study of patients attending lebanese school of dentistry. International Journal of Dentistry. 2018 May 17;2018.

40. Al-Mobeeriek A, AlDosari AM. Prevalence of oral lesions among Saudi dental patients. Annals of Saudi Medicine. 2009 Sep;29(5):365-8.

41. Solanki J, Gupta S. Prevalence of quid-induced lichenoid reactions among western Indian population. Journal of Experimental Therapeutics & Oncology. 2015 Jan 1;11(1)63-66.

42. Reichart PA, Warnakulasuriya S. Oral lichenoid contact lesions induced by areca nut and betel quid chewing: a mini review. Journal of Investigative and Clinical Dentistry. 2012 Aug;3(3):163-6.

43. Nanri H, Yamada Y, Itoi A, Yamagata E, Watanabe Y, Yoshida T, et al. Frequency of fruit and vegetable consumption and the oral health-related quality of life among Japanese elderly: A cross-sectional study from the Kyoto-Kameoka study. Nutrients. 2017 Dec;9(12):1362.

44. Soofi M, Pasdar Y, Matin BK, Hamzeh B, Rezaei S, Karyani AK, et al. Socioeconomic-related inequalities in oral hygiene behaviors: a cross-sectional analysis of the PERSIAN cohort study. BMC Oral Health. 2020 Dec;20(1):1-1.

45. Hsiao CN, Ko EC, Shieh TY, Chen HS. Relationship between areca nut chewing and periodontal status of people in a typical aboriginal community in Southern Taiwan. Journal of Dental Sciences. 2015 Sep 1;10(3):300- 8.