Abstract

For decades, psychopharmacology has focused on chemical modulation rather than biological repair. Emerging evidence across cellular, molecular, and systems neuroscience suggests that the adult brain retains dormant capacities for renewal that can be pharmacologically reactivated. Regenerative pharmacology reframes treatment as a process of biological reactivation, reawakening latent plasticity to rebuild damaged circuits rather than merely stabilizing neurotransmission. This commentary outlines the conceptual foundations, mechanistic architecture, and translational roadmap of this paradigm, spanning immature neuronal activation, glial reprogramming, cortical reopening of critical periods, and epigenetic or metabolic rejuvenation that resets cellular potential. Together, these processes define a multiscale model of brain repair that extends from chromatin to cognition. Integrating these advances within ethical, experience-guided clinical frameworks could transform therapy from neurotransmitter stabilization to genuine neural regeneration, marking a shift from pharmacology that controls the brain to pharmacology that teaches it to heal.

Keywords

Regenerative Pharmacology, Neuroplasticity reawakening, Neuropsychiatric disorders, Astrocytic reprogramming, Immature neurons, Epigenetic and metabolic rejuvenation, Critical period modulation, Experience-dependent brain repair

Reawakening the Regenerative Brain

The concept of regenerative pharmacology arises from a growing recognition that pharmacological agents can do more than modulate neurotransmission; they can rekindle the brain’s innate programs of renewal. For most of modern psychopharmacology, progress has been defined by control rather than repair. Antipsychotics dampened dopaminergic hyperactivity, antidepressants prolonged serotonergic tone, and anxiolytics suppressed excitation. These agents stabilized malfunctioning circuits, yet few restored the cellular vitality and adaptive flexibility that constitute true mental health [1,2]. Emerging evidence now reframes this limitation as an opportunity beneath the adult brain’s apparent rigidity lies a dormant capacity for rejuvenation and structural renewal [3,4].

Advances in stem-cell biology, cortical network mapping, and epigenetic modulation have converged on a provocative idea that pharmacology can do more than modulate neurotransmitters, it can reawaken intrinsic programs of plasticity. Drugs may one day reopen developmental-like windows, reactivate immature neurons, reprogram glia, and metabolically rejuvenate exhausted circuits. This shift marks the rise of regenerative pharmacology, a discipline aiming not merely to alleviate symptoms but to teach the brain how to heal itself. In the context of neuropsychiatric disorders, conditions rooted in maladaptive connectivity and impaired plasticity, this perspective offers a unifying goal to transform pharmacological intervention from chemical compensation to biological reactivation.

Latent Developmental Programs: Immature Neurons and Glial Reprogramming

The discovery that the adult mammalian brain retains limited neurogenic capacity in the subventricular zone (SVZ) and hippocampal dentate gyrus inspired decades of hope for cell-based regeneration [5,6]. In rodents, these germinal niches remain functionally active throughout life, supporting repair and behavioral adaptability. In contrast, in humans, this regenerative substrate appears markedly restricted, as SVZ neurogenesis declines sharply within the first few years of life. Nevertheless, some studies have reported evidence that hippocampal neurogenesis may persist in adults, albeit likely at very low levels—sparse, context-dependent, or perhaps even vestigial in nature [7,8]. This evolutionary divergence suggests that human brain plasticity must rely on alternative, more subtle cellular reserves.

Recent work points to a population of immature, prenatally generated neurons that persist in adulthood, particularly within associative cortices, the amygdala, and the claustrum [9,10]. These “neotenic” cells maintain a molecular phenotype of youth—expressing doublecortin, PSA-NCAM, and other developmental markers—yet remain functionally quiescent. They may serve as a latent reservoir of adaptability, capable of integrating into existing circuits under appropriate physiological or pharmacological cues. Reawakening these cells could represent a more feasible regenerative route than inducing de novo neuron formation.

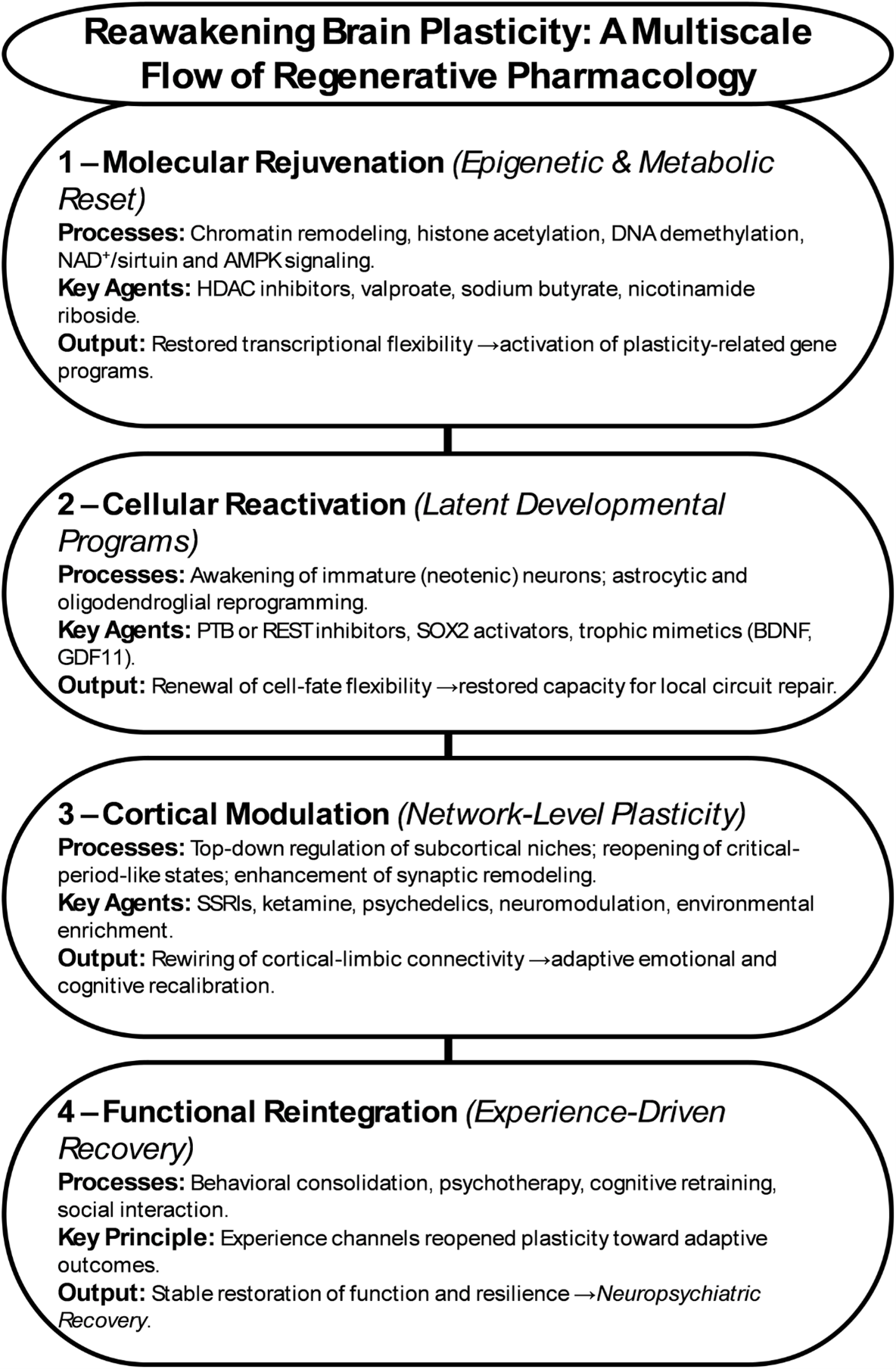

Parallel advances in glial reprogramming further expand this landscape. Astrocytes, once considered passive support cells, can be converted into neurons through genetic, epigenetic, or small-molecule interventions [11–13]. Modulating transcriptional regulators such as PTB, SOX2, or REST, or influencing metabolic and inflammatory states, has been shown to shift astrocytic identity toward neuronal lineages (Figure 1). Recent in vivo studies demonstrate that these interventions not only induce astrocyte-to-neuron conversion but also enable the resulting cells to integrate into existing circuits and restore local function [11,13]. This evidence establishes glial reprogramming as a biologically feasible and therapeutically promising pathway for neural repair, capable of reconstituting connectivity without exogenous cell transplantation.

Together, these findings redefine the architecture of regeneration in the human brain. Instead of generating new cells, regenerative pharmacology aims to awaken dormant developmental programs; reactivating immature neurons, redirecting glial trajectories, and restoring the cellular flexibility that underlies true neuropsychiatric recovery.

In disorders such as major depression, schizophrenia, and post-traumatic stress disorder, disrupted neuroplasticity manifests as synaptic loss, impaired learning flexibility, and maladaptive connectivity between cortical and limbic systems. Reinstating regenerative capacity could therefore restore the dynamic equilibrium between excitation, inhibition, and trophic support, providing a mechanistic route to durable recovery rather than symptomatic control.

Figure 1. Reawakening brain plasticity: a multiscale flow of regenerative pharmacology.

Cortical Modulation and Experience-Driven Plasticity

If dormant developmental programs provide the cellular foundation for regeneration, then cortical networks constitute its command architecture. The cortex is not merely the target of pharmacological intervention but the regulator of plasticity throughout the brain. Activity-dependent modulation of subcortical niches—especially the ventral SVZ and hippocampus—demonstrates that cortical excitability, oscillatory states, and neuromodulatory tone can directly influence stem-cell proliferation, glial differentiation, and neurotrophic signaling [14–18]. In this view, the cortex acts as a top-down driver of regeneration, capable of orchestrating cellular and molecular renewal when the appropriate physiological or pharmacological conditions are met [19].

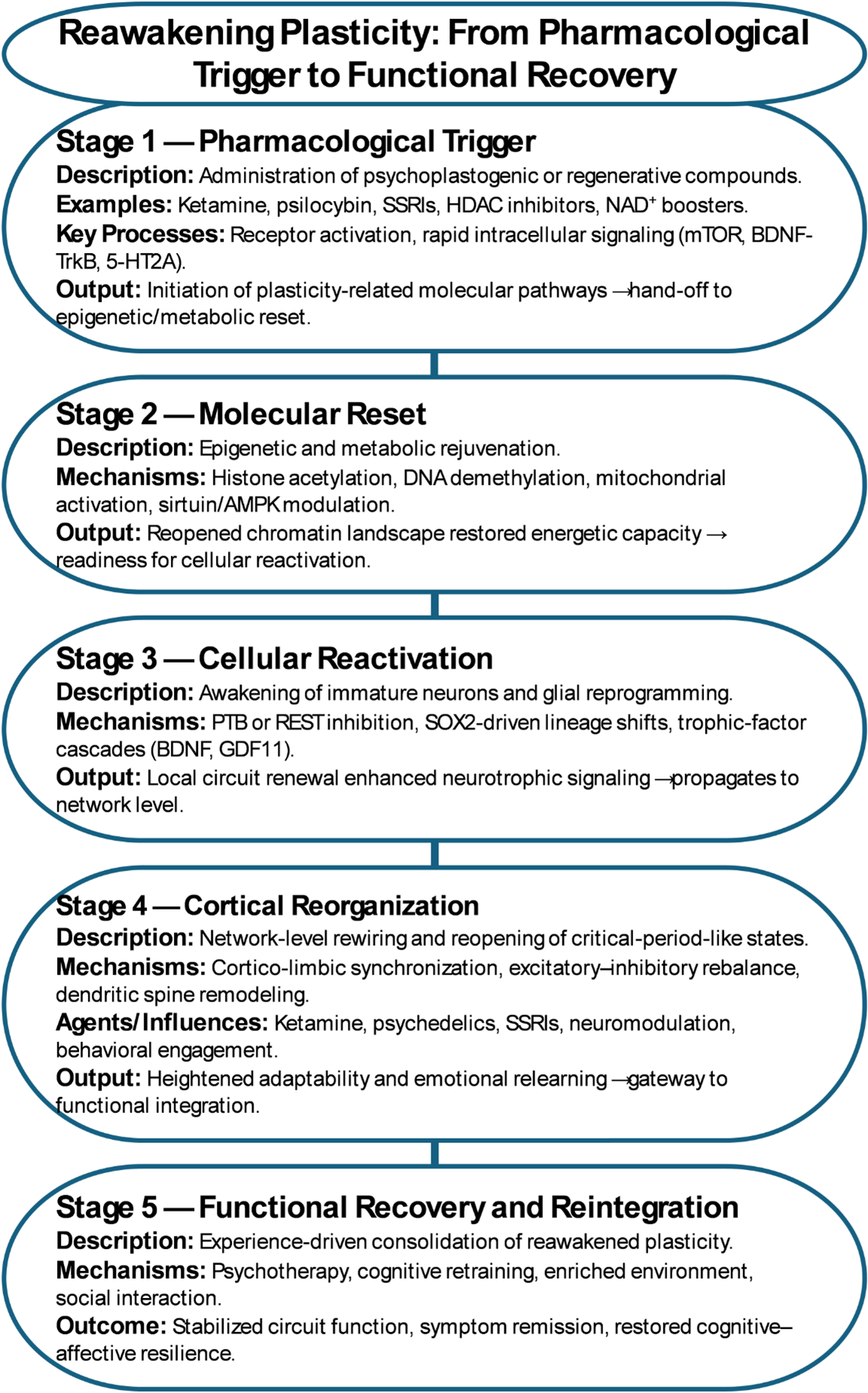

Psychiatric pharmacology provides clear evidence for this principle. The delayed onset of antidepressant efficacy—despite rapid synaptic effects on monoaminergic transmission—has long hinted that symptom recovery involves slower, structural reorganization. Chronic SSRI treatment enhances neurogenesis in animal models and alters dendritic morphology in cortical and limbic circuits, suggesting that sustained cortical remodeling underlies therapeutic response [20,21]. For example, chronic fluoxetine administration increases progenitor proliferation and neuronal differentiation in the hippocampal dentate gyrus, normalizes stress-induced dendritic atrophy, and enhances behavioral flexibility in rodent models of depression [22]. Rapid-acting antidepressants such as ketamine amplify this process by engaging glutamatergic burst activity, BDNF-TrkB signaling, and mTOR-dependent synaptogenesis within hours (Figure 1) [23]. Similarly, experimental models have shown that transient pharmacological activation of 5-HT2A-dependent intracellular signaling reopens developmental-like windows of plasticity (Figure 2) [24]. This results in rapid structural remodeling of cortical neurons, increased dendritic complexity, and sustained improvements in stress- and mood-related behaviors, providing direct evidence for reversible cortical rejuvenation through targeted receptor modulation. Collectively, these ‘psychoplastogenic’ agents demonstrate that cortical networks can be pharmacologically returned to a youthful, plastic state in which maladaptive connections may be rewritten, provided they are administered under controlled clinical or experimental conditions and paired with structured experience.

However, cortical reactivation alone is insufficient. Experience and environment determine whether reopened plasticity leads to repair or dysregulation. Behavioral engagement, psychotherapy, and enriched experience provide instructive signals that stabilize beneficial circuit changes, a concept paralleling rehabilitation in motor recovery [25,26]. Hence, pharmacological and experiential interventions must be coupled, allowing drugs to unlock plasticity and experience to direct it.

This convergence of cortical modulation, pharmacological reactivation, and guided experience represents the translational frontier of regenerative pharmacology. By reopening critical-period-like states in targeted circuits, drugs may enable the adult brain not merely to adapt, but to relearn and restore—transforming therapy from neurotransmitter tuning into network re-education.

Figure 2. Reawakening plasticity: from pharmacological trigger to functional recovery.

Epigenetic and Metabolic Rejuvenation — Resetting the Cellular Clock

If cortical modulation provides the system-level switch for plasticity, epigenetic and metabolic reprogramming defines the intracellular machinery that makes it possible. Every act of regeneration—whether the activation of an immature neuron or the conversion of an astrocyte—requires a permissive chromatin landscape and an energetic state capable of sustaining biosynthetic renewal. The adult brain’s relative resistance to change reflects not only circuit rigidity but also a progressive closure of its molecular potential. Gene expression patterns become canalized, mitochondrial dynamics slow, and chromatin marks of development are replaced by those of stability [27–29].

Pharmacological interventions can, in principle, reverse these molecular signatures of aging and constraint. Epigenetic modulators such as histone-deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors, DNA-methyltransferase antagonists, and histone-acetylation enhancers reopen transcriptional access to developmental and plasticity-related genes (Figure 2) [30,31]. Agents like valproate or sodium butyrate have been shown to enhance learning, promote neurotrophins expression, and facilitate reprogramming when combined with environmental enrichment. Similarly, small molecules influencing NAD+ metabolism, sirtuin activity, and AMPK signaling restore mitochondrial flexibility and redox balance—features essential for the anabolic demands of neurite outgrowth and synaptogenesis (Figure 1) [32–35].

This bioenergetic rejuvenation is not merely supportive but instructive. Metabolic flux determines epigenetic state through cofactors such as acetyl-CoA, α-ketoglutarate, and NAD+ that directly regulate chromatin-modifying enzymes [36]. Each of these metabolites functions as both an energy substrate and a chromatin cofactor. Acetyl-CoA fuels histone acetyltransferases, α-ketoglutarate supports demethylases such as TET and Jumonji-domain enzymes, and NAD+ activates sirtuin deacetylases, thereby linking metabolism directly to gene-expression control [37]. Thus, pharmacological restoration of mitochondrial health can reactivate gene networks associated with youthful plasticity. The emerging field of mitochondrial pharmacology is beginning to intersect with psychiatry, linking metabolic normalization to cognitive resilience and antidepressant response [38].

Furthermore, converging evidence indicates that coordinated modulation of chromatin remodeling and redox–sirtuin signaling can reinstate transcriptional flexibility in neural cells [30,35]. By restoring histone acetylation dynamics and mitochondrial redox balance, these interventions re-engage developmental gene programs and neurotrophin expression, suggesting that targeted rejuvenation of epigenetic and metabolic pathways may unlock dormant regenerative potential within the adult brain.

Taken together, these findings define a molecular infrastructure of regeneration. Epigenetic flexibility reopens the genome’s capacity for change, while metabolic rejuvenation supplies the energy to execute it. When integrated with cortical and cellular reactivation, these processes form a coherent hierarchy from chromatin to circuit through which regenerative pharmacology can transform therapeutic design. Drugs that reset the cellular clock may one day serve as catalysts for enduring recovery, allowing the adult brain to regain a measure of its developmental vitality without losing the stability that defines maturity. Candidate compounds currently under investigation include NAD+ precursors such as nicotinamide riboside, sirtuin-activating molecules including resveratrol and SRT1720, and HDAC inhibitors such as sodium butyrate and valproate, which together demonstrate the feasibility of pharmacologically re-engaging epigenetic youth programs [39–41].

Towards Regenerative Pharmacology—From Modulation to Reprogramming

The emerging convergence of cellular, cortical, and molecular insights heralds the emergence of a new therapeutic paradigm in regenerative pharmacology. This framework diverges from the traditional psychopharmacological model of chemical compensation and instead aims to reprogram the brain’s intrinsic mechanisms of repair and renewal (Table 1). Its central premise is that recovery from neuropsychiatric illness depends not merely on modulating neurotransmission but on reactivating dormant plasticity programs that operate across multiple biological scales, encompassing gene regulatory networks, cellular phenotypes, circuit connectivity, and systems integration (Figure 2) [42–44].

|

Domain |

Mechanistic Focus |

Representative Modulators/ Interventions |

Regenerative Outcome |

|

Epigenetic/ Metabolic Rejuvenation |

Chromatin remodeling, histone acetylation, DNA demethylation, mitochondrial and NAD+/sirtuin signaling. |

HDAC inhibitors (valproate, sodium butyrate), DNMT antagonists, nicotinamide riboside, AMPK activators. |

Reopened transcriptional programs; restored energy metabolism; enhanced genomic flexibility enabling plasticity-related gene expression. |

|

Cellular Reactivation |

Awakening of immature (neotenic) neurons; astrocytic and oligodendroglial reprogramming; trophic factor signaling. |

PTB or REST inhibition, SOX2 activation, GDF11/BDNF mimetics, small-molecule neurogenic enhancers. |

Renewal of cell-fate flexibility; restoration of local microcircuits; replenishment of support cell functionality. |

|

Cortical/ Network Modulation |

Reopening of critical-period-like states; excitatory–inhibitory rebalance; synaptic remodeling and dendritic spine formation. |

SSRIs, ketamine, psychedelics (psilocybin, LSD), neuromodulation, behavioral enrichment. |

Reorganization of cortico-limbic circuits; increased adaptability and emotional relearning; network-level homeostasis. |

|

Experiential/ Behavioral Integration |

Guided use of reopened plasticity via cognitive, social, and environmental inputs. |

Psychotherapy, cognitive retraining, rehabilitation, enriched environments. |

Stabilization of new circuits; functional recovery and long-term resilience; conversion of molecular reactivation into behavioral restoration. |

At the cellular level, immature neurons and glia constitute the biological reserve through which structural renewal may be achieved. At the network level, cortical modulation provides the control interface capable of reopening critical periods and guiding adaptive rewiring. At the molecular level, epigenetic and metabolic rejuvenation supply the enabling conditions that determine whether reprogramming can occur. Together, these domains form a multi-scale hierarchy of intervention, extending from chromatin to cognition, through which pharmacology can restore not only neurotransmitter balance but also the underlying biological capacity for adaptation and repair [45–47].

This hierarchical interaction reflects how molecular rejuvenation enables cellular reactivation, which in turn permits circuit-level reorganization and behavioral restoration. For instance, mitochondrial and chromatin remodeling can re-enable transcriptional programs required for neuronal differentiation, while cortical network modulation channels these reactivated neurons into adaptive learning loops [45–47]. Such cross-scale coupling supports the emerging view that lasting recovery in neuropsychiatric disease depends on coordinated regeneration across molecular, cellular, and systems levels rather than isolated receptor modulation [48,49].

To operationalize this framework, regenerative outcomes should be delineated through quantifiable biomarkers that transcend symptom-based metrics. These can be structured across four complementary tiers: (1) epigenetic and metabolic rejuvenation, indexed by NAD+/sirtuin ratios, histone-acetylation profiles, and mitochondrial redox indices; (2) cellular reactivation, captured through markers of immature neurons such as doublecortin and PSA-NCAM expression, or GFAP-to-NeuN conversion rates; (3) network modulation, measured via fMRI-derived network flexibility, EEG-theta coherence, and indices of excitatory–inhibitory balance; and (4) behavioral integration, assessed through learning-rate dynamics, cognitive-adaptability metrics, and indicators of functional resilience. Collectively, these quantitative strata delineate a methodological scaffold for regenerative pharmacology, linking molecular rejuvenation to circuit reorganization and behavioral recovery through objective, data-driven endpoints.

In clinical and translational terms, each behavioral domain corresponds to characteristic deficits across major neuropsychiatric disorders. In major depressive disorder, reduced cognitive flexibility and slowed learning rates reflect diminished hippocampal and prefrontal plasticity. In schizophrenia, disturbances in working-memory updating and social cognition are associated with disrupted excitation–inhibition balance and network desynchronization. In post-traumatic stress disorder, maladaptive fear generalization and failure of extinction learning exemplify aberrant reconsolidation of memory circuits. These phenotypes represent the behavioral manifestations of underlying molecular and cellular rigidity.

Accordingly, improvements in learning-rate dynamics, cognitive adaptability, or resilience during treatment can serve as functional biomarkers of successful plasticity re-engagement. By linking measurable behavioral change to its neurobiological substrate, regenerative pharmacology provides a framework for assessing recovery not only as symptom remission but as restoration of adaptive capacity within the brain’s multiscale architecture [50–52].

Translating this framework into practice will require new methodologies for measuring regeneration in vivo.

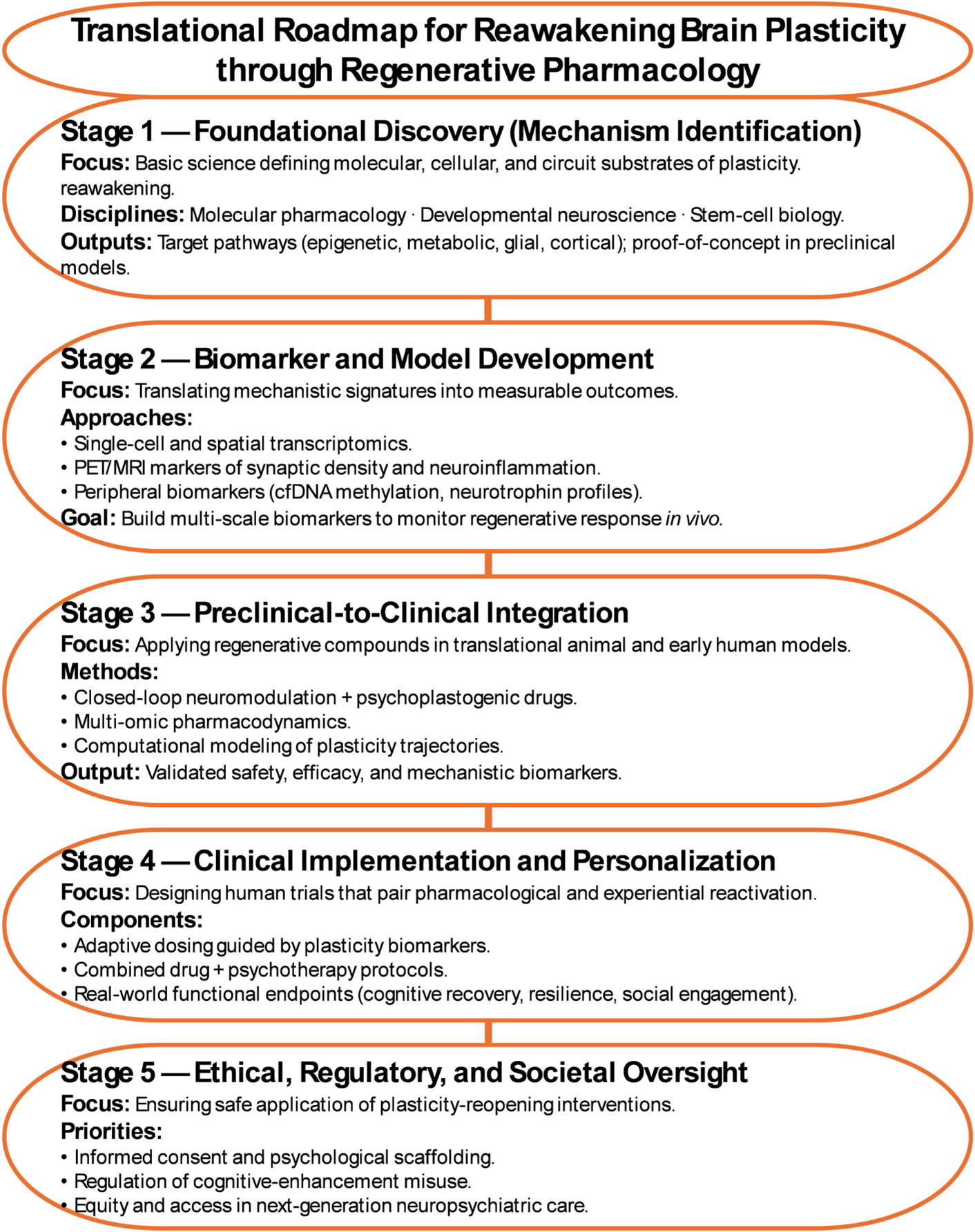

Translational roadmap and clinical integration

Advancing regenerative pharmacology from conceptual models to therapeutic application requires structured translational frameworks. A practical roadmap envisions a stepwise clinical architecture that integrates pharmacological reactivation with biopsychosocial co-therapies. Early-phase studies could combine agents known to reopen transient plasticity windows such as ketamine, valproate, or psilocybin with structured cognitive retraining, psychotherapy, or enriched-environment programs that channel neural flexibility toward adaptive network rewiring.

Adaptive phase I/II trial designs should embed multimodal endpoints coupling biological and behavioral markers: synaptic-density PET, resting-state and task-based fMRI for network reorganization, electrophysiological metrics of cortical excitability, and standardized measures of cognitive and affective recovery. Integration of these datasets under Good Machine Learning Practice principles will ensure reproducibility and bias control when linking molecular, imaging, and behavioral signatures of regeneration.

Together, these strategies create a translational bridge from mechanism to therapy, defining how pharmacological reopening of plasticity can be safely and effectively transformed into measurable functional recovery.

Ethical and clinical reorientation

Multi-modal imaging of synaptic density, transcriptomic profiling of peripheral biomarkers, and circuit-level electrophysiology could serve as proxies for cellular renewal and network reorganization [53–55]. The design of next-generation compounds will need to integrate systems pharmacology, stem-cell biology, and computational modeling, enabling drugs to act not as single-target ligands but as orchestrators of adaptive cascades.

Crucially, regenerative pharmacology will also demand ethical and clinical reorientation. Drugs that reopen developmental programs must be paired with structured behavioral and environmental scaffolds to ensure that reactivated plasticity leads to recovery rather than maladaptation. Psychotherapy, cognitive training, and social engagement may thus become essential co-therapies, transforming pharmacological treatment into a biopsychosocial process of guided regeneration.

The next revolution in neuroscience will not hinge on faster receptor kinetics or novel ligands, but on our ability to pharmacologically unlock the brain’s latent potential for self-repair. In doing so, regenerative pharmacology offers a unifying vision of medicine that restores, rebalances, and ultimately reawakens the human mind.

Future Perspectives

Realizing the promise of regenerative pharmacology will require a new scientific and clinical ecosystem one that bridges molecular, cellular, and behavioral scales. Pharmacologists can identify the compounds that reopen plasticity; neuroscientists can map the circuits they transform; psychiatrists and psychologists must define how reactivated plasticity translates into meaningful recovery. This integrative vision demands cross-disciplinary consortia, combining single-cell transcriptomics, advanced neuroimaging, and computational modeling to capture the multiscale signatures of regeneration in the living brain (Figure 3) [49,56].

Figure 3. Translational roadmap for reawakening brain plasticity through regenerative pharmacology.

Safety and controlled plasticity

Manipulating developmental programs requires rigorous safeguards to prevent maladaptive outcomes. A balanced framework should distinguish between adaptive and maladaptive reactivation by incorporating both spatial and temporal precision in the reopening of critical periods. Pharmacological tools must favor graded dosing, reversible modulators, and circuit-specific targeting to minimize excessive cortical excitation or uncontrolled synaptogenesis. Beyond pharmacology, safety also depends on coupling reactivated plasticity with behavioral and environmental scaffolds including psychotherapy, cognitive rehabilitation, and enriched learning contexts to channel neural flexibility toward stable and functional recovery.

To enable objective monitoring, a Controlled Plasticity Index (CPI) can be envisioned as a conceptual biomarker that integrates electrophysiological balance (e.g., excitatory–inhibitory ratios), molecular markers of plasticity-related gene expression, and behavioral adaptability metrics. We propose the CPI as a hypothetical, integrative framework rather than a validated clinical instrument, intended to guide early-stage monitoring and trial design in regenerative pharmacology. Such a multidimensional framework would allow dynamic assessment of how pharmacological and experiential interventions modulate neural flexibility. Incorporating CPI-based measures into early-phase trials could help define safe operational windows for regenerative pharmacology, guiding dose titration, detecting maladaptive network states, and quantifying the threshold between restorative and destabilizing plasticity.

Ethical design and clinical translation

Equally critical is the ethical design of interventions that manipulate developmental programs. Reawakening plasticity without proper guidance may cause instability, so it is essential to pair pharmacological reprogramming with structured experiential frameworks such as rehabilitation, psychotherapy, and enriched environments. The outcome depends on this alignment between molecular and experiential modulation, which determines whether renewal results in genuine recovery. Regulatory frameworks and clinical trials must therefore evolve to evaluate not only symptom reduction but also restorative function, adaptability, and resilience as central therapeutic goals.

As neuroscience advances beyond receptor modulation toward circuit and cellular rejuvenation, a new therapeutic philosophy is emerging. The next generation of drugs will not aim to suppress dysfunction within the brain but to enable it to rebuild its own networks. In this process of reawakening, psychiatry and pharmacology may finally converge on a shared goal that centers on restoring the brain’s intrinsic capacity for change, adaptation, and healing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Availability of Data and Materials

Not applicable.

Funding

There are no funds to declare for this work.

Authors' Contributions

M.N. designed and wrote the main manuscript text.

References

2. Baldessarini RJ. The impact of psychopharmacology on contemporary psychiatry. Can J Psychiatry. 2014 Aug;59(8):401–5.

3. Bouchard J, Villeda SA. Aging and brain rejuvenation as systemic events. J Neurochem. 2015 Jan;132(1):5–19.

4. Naffaa MM. Disruptions in Adult Neurogenesis: Mechanisms, Pathways, and Therapeutic Strategies for Cognitive Decline and Neurodegenerative Diseases in Aging. Nat Cell Sci. 2025;3(1):27–53.

5. Alvarez-Buylla A, Garcia-Verdugo JM. Neurogenesis in adult subventricular zone. J Neurosci. 2002 Feb 1;22(3):629–34.

6. Bond AM, Ming GL, Song H. Adult Mammalian Neural Stem Cells and Neurogenesis: Five Decades Later. Cell Stem Cell. 2015 Oct 1;17(4):385–95.

7. Ming GL, Song H. Adult neurogenesis in the mammalian brain: significant answers and significant questions. Neuron. 2011 May 26;70(4):687–702.

8. Kumar A, Pareek V, Faiq MA, Ghosh SK, Kumari C. ADULT NEUROGENESIS IN HUMANS: A Review of Basic Concepts, History, Current Research, and Clinical Implications. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2019 May 1;16(5-6):30–7.

9. Bonfanti L, La Rosa C, Ghibaudi M, Sherwood CC. Adult neurogenesis and "immature" neurons in mammals: an evolutionary trade-off in plasticity? Brain Struct Funct. 2024 Nov;229(8):1775–93.

10. Sorrells SF, Paredes MF, Velmeshev D, Herranz-Pérez V, Sandoval K, Mayer S, et al. Immature excitatory neurons develop during adolescence in the human amygdala. Nat Commun. 2019 Jun 21;10(1):2748.

11. Tan Z, Qin S, Liu H, Huang X, Pu Y, He C, et al. Small molecules reprogram reactive astrocytes into neuronal cells in the injured adult spinal cord. J Adv Res. 2024 May;59:111–27.

12. Wang F, Cheng L, Zhang X. Reprogramming Glial Cells into Functional Neurons for Neuro-regeneration: Challenges and Promise. Neurosci Bull. 2021 Nov;37(11):1625–36.

13. Wu Z, Parry M, Hou XY, Liu MH, Wang H, Cain R, et al. Gene therapy conversion of striatal astrocytes into GABAergic neurons in mouse models of Huntington's disease. Nat Commun. 2020 Feb 27;11(1):1105.

14. Ruggiero RN, Rossignoli MT, Marques DB, de Sousa BM, Romcy-Pereira RN, Lopes-Aguiar C, et al. Neuromodulation of Hippocampal-Prefrontal Cortical Synaptic Plasticity and Functional Connectivity: Implications for Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Front Cell Neurosci. 2021 Oct 11;15:732360.

15. Naffaa MM. Significance of the anterior cingulate cortex in neurogenesis plasticity: Connections, functions, and disorders across postnatal and adult stages. Bioessays. 2024 Mar;46(3):e2300160.

16. Naffaa MM, Khan RR, Kuo CT, Yin HH. Cortical regulation of neurogenesis and cell proliferation in the ventral subventricular zone. Cell Rep. 2023 Jul 25;42(7):112783.

17. Naffaa MM, Yin HH. A cholinergic signaling pathway underlying cortical circuit activation of quiescent neural stem cells in the lateral ventricle. Sci Signal. 2024 Sep 24;17(855):eadk8810.

18. Toda T, Parylak SL, Linker SB, Gage FH. The role of adult hippocampal neurogenesis in brain health and disease. Mol Psychiatry. 2019 Jan;24(1):67–87.

19. Naffaa MM. Neural circuit regulation of postnatal and adult subventricular zone neurogenesis: Mechanistic insights, functional models, and circuit-based neurological disorders. Arch Stem Cell Ther. 2024 Aug 22;5(1):14–21.

20. Segi-Nishida E. The Effect of Serotonin-Targeting Antidepressants on Neurogenesis and Neuronal Maturation of the Hippocampus Mediated via 5-HT1A and 5-HT4 Receptors. Front Cell Neurosci. 2017 May 16;11:142.

21. Rosas-Sánchez GU, Germán-Ponciano LJ, Guillen-Ruiz G, Cueto-Escobedo J, Limón-Vázquez AK, Rodríguez-Landa JF, et al. Neuroplasticity and Mechanisms of Action of Acute and Chronic Treatment with Antidepressants in Preclinical Studies. Biomedicines. 2024 Nov 29;12(12):2744.

22. Malberg JE, Eisch AJ, Nestler EJ, Duman RS. Chronic antidepressant treatment increases neurogenesis in adult rat hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2000 Dec 15;20(24):9104–10.

23. Kang MJY, Hawken E, Vazquez GH. The Mechanisms Behind Rapid Antidepressant Effects of Ketamine: A Systematic Review With a Focus on Molecular Neuroplasticity. Front Psychiatry. 2022 Apr 25;13:860882

24. Vargas MV, Dunlap LE, Dong C, Carter SJ, Tombari RJ, Jami SA, et al. Psychedelics promote neuroplasticity through the activation of intracellular 5-HT2A receptors. Science. 2023 Feb 17;379(6633):700–6.

25. Jeffers MS, Corbett D. Synergistic Effects of Enriched Environment and Task-Specific Reach Training on Poststroke Recovery of Motor Function. Stroke. 2018 Jun;49(6):1496–503.

26. Walker-Batson D, Smith P, Curtis S, Unwin DH. Neuromodulation paired with learning dependent practice to enhance post stroke recovery? Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2004;22(3-5):387–92.

27. Liu H, Song N. Molecular Mechanism of Adult Neurogenesis and its Association with Human Brain Diseases. J Cent Nerv Syst Dis. 2016 Jun 20;8:5–11.

28. Navarro Negredo P, Yeo RW, Brunet A. Aging and Rejuvenation of Neural Stem Cells and Their Niches. Cell Stem Cell. 2020 Aug 6;27(2):202–23.

29. Seng C, Luo W, Földy C. Circuit formation in the adult brain. Eur J Neurosci. 2022 Aug;56(3):4187–213.

30. Bae W, Ra EA, Lee MH. Epigenetic regulation of reprogramming and pluripotency: insights from histone modifications and their implications for cancer stem cell therapies. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2025 Mar 3;13:1559183.

31. Benatti BM, Adiletta A, Sgadò P, Malgaroli A, Ferro M, Lamanna J. Epigenetic Modifications and Neuroplasticity in the Pathogenesis of Depression: A Focus on Early Life Stress. Behav Sci (Basel). 2024 Oct 1;14(10):882.

32. Intlekofer KA, Berchtold NC, Malvaez M, Carlos AJ, McQuown SC, Cunningham MJ, et al. Exercise and sodium butyrate transform a subthreshold learning event into long-term memory via a brain-derived neurotrophic factor-dependent mechanism. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013 Sep;38(10):2027–34.

33. Perisic T, Zimmermann N, Kirmeier T, Asmus M, Tuorto F, Uhr M, et al. Valproate and amitriptyline exert common and divergent influences on global and gene promoter-specific chromatin modifications in rat primary astrocytes. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010 Feb;35(3):792–805.

34. Hyun DH, Lee J. A New Insight into an Alternative Therapeutic Approach to Restore Redox Homeostasis and Functional Mitochondria in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Antioxidants (Basel). 2021 Dec 21;11(1):7.

35. Mormone E, Iorio EL, Abate L, Rodolfo C. Sirtuins and redox signaling interplay in neurogenesis, neurodegenerative diseases, and neural cell reprogramming. Front Neurosci. 2023 Feb 1;17:1073689.

36. Yu X, Ma R, Wu Y, Zhai Y, Li S. Reciprocal Regulation of Metabolic Reprogramming and Epigenetic Modifications in Cancer. Front Genet. 2018 Sep 19;9:394.

37. Kaelin WG Jr, McKnight SL. Influence of metabolism on epigenetics and disease. Cell. 2013 Mar 28;153(1):56–69.

38. Kim Y, Vadodaria KC, Lenkei Z, Kato T, Gage FH, Marchetto MC, et al. Mitochondria, Metabolism, and Redox Mechanisms in Psychiatric Disorders. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2019 Aug 1;31(4):275–317.

39. Berven H, Kverneng S, Sheard E, Søgnen M, Af Geijerstam SA, Haugarvoll K, et al. NR-SAFE: a randomized, double-blind safety trial of high dose nicotinamide riboside in Parkinson's disease. Nat Commun. 2023 Nov 28;14(1):7793.

40. Gueguen C, Palmier B, Plotkine M, Marchand-Leroux C, Besson VC. Neurological and histological consequences induced by in vivo cerebral oxidative stress: evidence for beneficial effects of SRT1720, a sirtuin 1 activator, and sirtuin 1-mediated neuroprotective effects of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibition. PLoS One. 2014 Feb 21;9(2):e87367.

41. Govindarajan N, Agis-Balboa RC, Walter J, Sananbenesi F, Fischer A. Sodium butyrate improves memory function in an Alzheimer's disease mouse model when administered at an advanced stage of disease progression. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;26(1):187–97.

42. Marei HE. Neural Circuit Mapping and Neurotherapy-Based Strategies. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2025 Jul 26;45(1):75.

43. Diniz CRAF, Crestani AP. The times they are a-changin': a proposal on how brain flexibility goes beyond the obvious to include the concepts of "upward" and "downward" to neuroplasticity. Mol Psychiatry. 2023 Mar;28(3):977–92.

44. Gazerani P. The neuroplastic brain: current breakthroughs and emerging frontiers. Brain Res. 2025 Jul 1;1858:149643.

45. Patton MH, Blundon JA, Zakharenko SS. Rejuvenation of plasticity in the brain: opening the critical period. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2019 Feb;54:83–9.

46. Shen Y, Luchetti A, Fernandes G, Do Heo W, Silva AJ. The emergence of molecular systems neuroscience. Mol Brain. 2022 Jan 4;15(1):7.

47. Bonfanti L, Charvet CJ. Brain Plasticity in Humans and Model Systems: Advances, Challenges, and Future Directions. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Aug 28;22(17):9358.

48. Castrén E, Hen R. Neuronal plasticity and antidepressant actions. Trends Neurosci. 2013 May;36(5):259–67.

49. Krejcar O, Namazi H. Multiscale brain modeling: bridging microscopic and macroscopic brain dynamics for clinical and technological applications. Front Cell Neurosci. 2025 Feb 19;19:1537462.

50. Price RB, Duman R. Neuroplasticity in cognitive and psychological mechanisms of depression: an integrative model. Mol Psychiatry. 2020 Mar;25(3):530–43.

51. Maren S, Holmes A. Stress and Fear Extinction. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016 Jan;41(1):58–79.

52. Caroni P, Donato F, Muller D. Structural plasticity upon learning: regulation and functions. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012 Jun 20;13(7):478–90.

53. Cadwell CR, Scala F, Li S, Livrizzi G, Shen S, Sandberg R, et al. Multimodal profiling of single-cell morphology, electrophysiology, and gene expression using Patch-seq. Nat Protoc. 2017 Dec;12(12):2531–53.

54. Khan AF, Iturria-Medina Y. Beyond the usual suspects: multi-factorial computational models in the search for neurodegenerative disease mechanisms. Transl Psychiatry. 2024 Sep 23;14(1):386.

55. Ramezani M, Ren Y, Cubukcu E, Kuzum D. Innovating beyond electrophysiology through multimodal neural interfaces. Nat Rev Electr Eng. 2025 Jan;2(1):42–57.

56. Camunas-Soler J. Integrating single-cell transcriptomics with cellular phenotypes: cell morphology, Ca2+ imaging and electrophysiology. Biophys Rev. 2023 Dec 18;16(1):89–107.