Abstract

Background: Postnatal care (PNC) service can be described as the attention to mental, physical, and physiological rehabilitation. At the physiological level, postpartum haemorrhage is a leading cause of death among postnatal women.

Objective: The aim of this report is to advance experiential opinion on barriers to PNC services in Nigeria.

Method: This was an autobiographical case report.

Observations being reported: Barriers to the utilization of PNC services cuts across Health Workers’ training needs as well as low perception of its importance amongst women of reproductive age.

Conclusion: The take home message we learnt from our experience is that adequate postnatal care is necessary not just for the immediate health of the mother and child but that it’s also a stepping-stone to the next pregnancy experience. This forms the basis for the continuum of care from pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period by skilled providers in a comprehensive and integrated manner.

Keywords

Maternal health, Postnatal care, Auto-biographical case report, Postpartum haemorrhage, Women of reproductive age

Introduction

Postnatal depression and postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) are known public health issues. In Nigeria, report indicates the prevalence could be over 35% for depression, and up to 68% for PPH [1]. However, some studies report very low (<10%) prevalence of PPH [2], which seems unrealistic and possibly minimizes the need for further stringent attention. It has long been established that screening service constitutes a preventive medicine practice [3]. Delta State government has demonstrated commitment to maternal and childcare service. Research reports have highlighted services provided in this focus area [4-7]. However, the specific issue of postnatal care still requires discourse.

In a study that investigated “healthcare providers’ ability to identify and support women with depression from the antenatal period through to 6 months postnatal, it was found that only 31/218 (14.22%) women were assessed for postnatal depression, out of which 28 were offered counselling [8].

Other studies have identified challenges that occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic has been highlighted [9], as well as consideration of the client autonomy factor [10]. Hence the objective of this commentary is to narrate a personal experience that spanned across three pregnancies.

Case Presentation

Demography

I am a forty-years old graduate and mother of three (3) children. My postnatal journey started after I had my first baby in 2012 and my experience was similar in all three deliveries, either per-vagina or Cesarean section.

Relevant medical history

As an average Nigerian woman, my only knowledge or ideology of postnatal care was the conventional traditional care locally known as “Omugwo”; where your mother, mother-in-law or any older woman who had given birth before comes to live with you for a certain period of time to render care and support to you and the baby. This concept has gained popularity over the years, so much so that it’s something every pregnant woman looks forward to. Herbal remedies, hot water massages, and spicy soup diets (pepper soup) were the order of the day. These were believed to aid recovery and promote milk production.

The Commentary

Clinical case under focus

Maternal: In one of my hot water baths/massages, after my second baby, I became lightheaded in the bathroom and almost passed out…

Infant: My first baby was seriously jaundiced, but I was advised not to take him to clinic, stating that they would transfuse my baby and use other medications that will have lasting side effects on the child.

Diagnosis and interventions

…but for the timely intervention of my mother who quickly poured cold water on me. She later explained that because I had lost a lot of blood during the prolonged delivery, the little blood in circulation was quickly depleted from my brain because the water was too hot for me to handle.

According to beliefs, the most potent remedy for jaundice was an herbal drink prepared from unripe pawpaw fruit fermented in water, as well as sunbathing in the morning. Although I was concerned about my baby, I had to stick with the options suggested by my family.

The adverse event and PNC service considerations

I never had skilled or professional care during the periods after delivery; infact, the best way to caption it would be “I never expected any professional care during the postnatal period because I wasn’t aware of any such structured service being available.

If I had been given orientation about the availability of professional standardized postnatal care services, I would have availed myself of it whilst undergoing the conventional traditional one. This is because there were some drawbacks or risks involved in receiving a care that is not standardized or structured; you and your baby are usually left at the mercy of your caregiver in some of the following ways:

- The person’s wealth of experience.

- The person’s cultural or spiritual beliefs

- The person’s nature/temperament

- The person’s strength/ capabilities

- The person’s educational level

Highlight

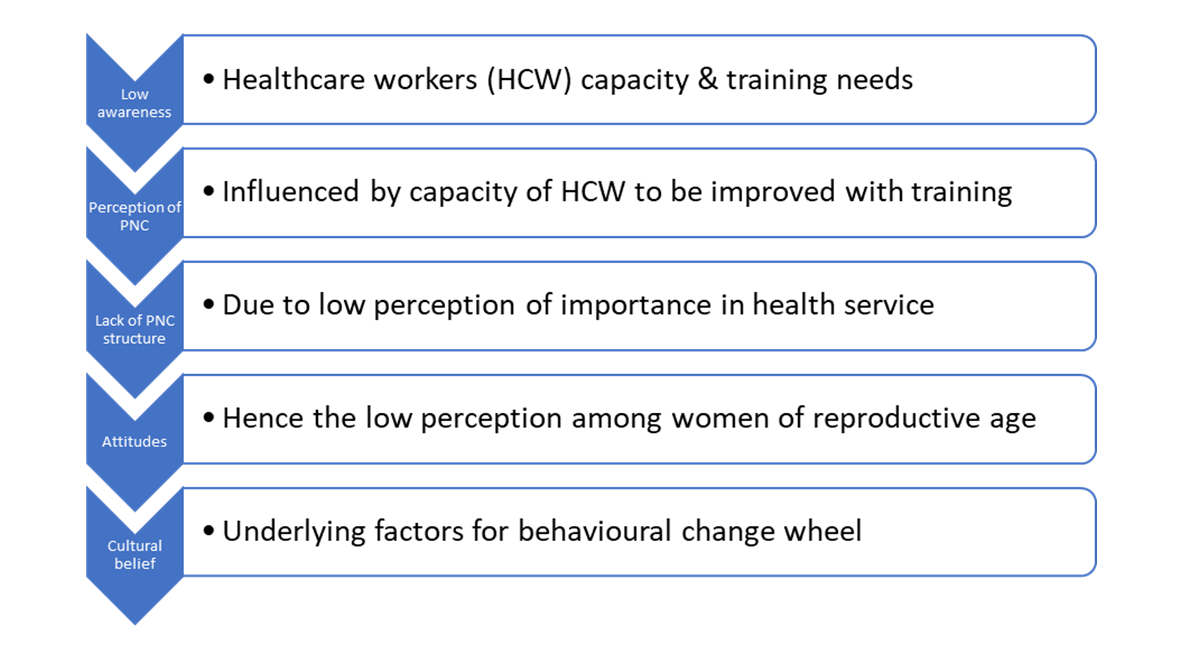

All through these ordeals, I never sought for skilled/professional care because I didn’t even know if anything of such existed. The barriers to accessing postnatal care can be itemized under five headings and summarized graphically (Figure 1):

Figure 1. Conceptual perspective of how HCW capacity can improve PNC services.

Low awareness about postnatal care (PNC) services

As opposed to the wide spread of information on the importance of antenatal care, increasing its demand both in the rural and urban settings, there seemed to be little, or no importance attached to skilled postnatal care as evident in the level of awareness and demand. Also, the family/community support structure for PNC is virtually nonexistent as against support for antenatal care.

Perceived importance of PNC services

Immediately I discovered I was pregnant; I knew the next thing to do was to register in a clinic for antenatal checkup; this was based on the fact that the average woman understands the importance of regular checkups during the period of pregnancy. This same level of importance was never given to care after delivery, particularly when there seemed to be no obvious life-threatening complications.

Lack of a structured PNC schedule

After registering at the clinic, I was given a schedule for my next visit. This continued throughout the period of pregnancy, ranging from 6 weeks apart, to four weeks, to every two weeks and then weekly as I came closer to term. It was so structured that it would be recorded in my card, and I will be singing with the date at home. However, there was never a time I was given a schedule of visit after delivery for postnatal care. Thus, you just leave the hospital with no clue as to your next line of action concerning your mental, physical or physiological recovery and the health of my baby, except for the immunization schedule visits.

The attitude of the health workers

The health service providers never showed much enthusiasm themselves regarding postnatal care. They gave little or no health education concerning postnatal care, either during the antenatal visits or during discharge. The closest I got to getting a professional postnatal care was after my last baby’s delivery which was in a private maternity home. I had taken my baby for her 6 weeks immunization shot when the midwife called me to come into her office. She asked me to lie down and then palpated my abdomen. She seemed to be satisfied with what she saw and said I could go. In other cases, the health workers may just ask you casually “How you dey?” or How baby?”, you respond “fine”, and that was it.

Cultural beliefs and practices

My ideology of postnatal care was shaped by the surrounding cultural norms and practices. Same can be said for a wide range of women, as the traditional postnatal care structure “omugwo” is held in very high esteem amongst women, irrespective of educational status or social class.

Discussion in Brief

To provide a brief substantiation of how the literature supports the thematic barriers outlined, determinants of maternal-and-child healthcare services have been identified to differ between communities [11], but does include the women’s autonomy [10], as well as preceding antenatal care, mode of delivery and marital statsus [12]. This is supported by reports from other African countries such as Ghana [13], Kenya [14], Rwanda [15,16], Tanzania [16,17], and Uganda [16,18].

Further, report has highlighted three major organizational inadequacies on the part of healthcare providers and another two for the women/clients. The organizational factors include poor capacity to offer quality care, manpower shortage and lack of manpower training. The service users’ factors are related and indicated to include lack of awareness of what quality postnatal care entails, and low service expectation [8].

Conclusion

I learnt from my experience that adequate postnatal care is necessary not just for the immediate health of the mother and child but it’s also a stepping-stone to the next pregnancy experience. I recommend that awareness of the importance and availability of PNC services be created to drive demand for it. Also, the health workforce should make it a point of duty to orient new mothers of the PNC schedule and follow up on defaulters where necessary.

References

2. Adebayo T, Adefemi A, Adewumi I, Akinajo O, Akinkunmi B, Awonuga D, et al. Burden and outcomes of postpartum haemorrhage in Nigerian referral-level hospitals. BJOG.2024 Aug;131 Suppl 3:64-77.

3. Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry.1987 Jun;150:782-6.

4. Ibobo JA, Chime H, Nwose EU. Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in Delta State of Nigeria: Evaluation of the early infant diagnosis program. Journal of Health Science Research. 2018 Jan 1;3(1):16-23.

5. Okwe UN, Chime H, Nwose EU. Factors influencing the acceptance of HPV vaccine among civil servants in Delta State Secretariat. International Journal of Reproduction, Contraception, Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2019 Jan 1;8(4):1227-32.

6. Okwe UN, Chime H, Nwose EU. Factors influencing the acceptance of cervical cancer screening among civil servants in Delta State Secretariat. International Journal of Reproduction, Contraception, Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2019 Jan 1;8(4):1380-6.

7. Orove AA, Garba A, Orru MO, Otovwe A, Igumbor EO, Nwose EU. Gestational diabetes management postpartum in primary healthcare facilities: Mini review update on Delta State Nigeria. Clinical Medical Reviews and Reports. 2020 Jan 1;2(7).

8. Ayinde OO, Oladeji BD, Abdulmalik J, Jordan K, Kola L, Gureje O. Quality of perinatal depression care in primary care setting in Nigeria. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018 Nov 22;18(1):879

9. Balogun M, Banke-Thomas A, Sekoni A, Boateng GO, Yesufu V, Wright O, et al. Challenges in access and satisfaction with reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health services in Nigeria during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional survey. PLoS One. 2021 May 7;16(5):e0251382.

10. Odusina EK, Oladele OS. Is there a link between the autonomy of women and maternal healthcare utilization in Nigeria? A cross-sectional survey. BMC Womens Health. 2023 Apr 6;23(1):167.

11. Adeyemo EO, Oluwole EO, Kanma-Okafor OJ, Izuka OM, Odeyemi KA. Prevalence and predictors of postpartum depression among postnatal women in Lagos, Nigeria. Afr Health Sci. 2020 Dec;20(4):1943-54.

12. Adewuya AO, Fatoye FO, Ola BA, Ijaodola OR, Ibigbami SM. Sociodemographic and obstetric risk factors for postpartum depressive symptoms in Nigerian women. J Psychiatr Pract. 2005 Sep;11(5):353-8.

13. Sumankuuro J, Crockett J, Wang S. Sociocultural barriers to maternity services delivery: a qualitative meta-synthesis of the literature. Public Health. 2018 Apr;157:77-85.

14. Roney E, Morgan C, Gatungu D, Mwaura P, Mwambeo H, Natecho A, et al. Men's and women's knowledge of danger signs relevant to postnatal and neonatal care-seeking: A cross sectional study from Bungoma County, Kenya. PLoS One. 2021 May 13;16(5):e0251543.

15. Williams P, Murindahabi NK, Butrick E, Nzeyimana D, Sayinzoga F, Ngabo B, et al. Postnatal care in Rwanda: facilitators and barriers to postnatal care attendance and recommendations to improve participation. J Glob Health Rep. 2019;3(1):20190601.

16. Matovelo D, Boniphace M, Singhal N, Nettel-Aguirre A, Kabakyenga J, Turyakira E, et al. Evaluation of a comprehensive maternal newborn health intervention in rural Tanzania: single-arm pre-post coverage survey results. Glob Health Action. 2022 Dec 31;15(1):2137281.

17. LeFevre A, Mpembeni R, Kilewo C, Yang A, An S, Mohan D, Mosha I, et al. Program assessment of efforts to improve the quality of postpartum counselling in health centers in Morogoro region, Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018 Jul 4;18(1):282.

18. Rutaremwa G, Wandera SO, Jhamba T, Akiror E, Kiconco A. Determinants of maternal health services utilization in Uganda. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015 Jul 17;15:271.