Abstract

Background: Assessing patient reported outcomes (PRO) in conjunction with laboratory results inform better on the wellbeing of patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. We assessed PRO in relation to sociodemographic characteristics and viral load (VL) in HIV infected patients on antiretroviral therapy in a tertiary level hospital in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

Methods: This cross-sectional study enrolled adults who were on ART treatment for >six months. PRO was assessed using validated questionnaires. HRQoL was assessed using the EuroQol 5 Dimension 3 level (EQ-5D-3L) questionnaire whereby patients who reported any problem had poor HRQoL, while patients who reported no problem had good HRQoL. Adherence was assessed using a 7-day recall. Care satisfaction was assessed using patient satisfaction questionnaire short-form (PSQ-18). We recorded patients’ demographics and their current viral load.

Results: Of the 800 enrolled patients, 592 (74%) were female and in age group 30-59 [680/800, (85%)]. Overall 606/800 (75.75%) had good HRQoL as they reported no problem in all dimensions of EQ-5D-3L i.e. mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain and discomfort and anxiety or depression. Detectable VL was associated with problems across all the 5 dimensions. Most patients (83%) were generally satisfied with care, the mean score for general satisfaction was 3.84 ± 0.77, Cronbach’s alpha =0.72. Patients were dissatisfied with financial aspects of care (mean score 3.10 ± 0.65 Cronbach’s alpha=0.69). Most patients 693/800 (86.6%) reported high ART adherence of = 95%. Significantly majority of participants with high adherence 522/590 (88.47%) had undetectable VL, P value <0.001.

Conclusions: Participants in this setting reported good quality of life and high adherence to ART. High adherence was significantly associated with undetectable VL. Participants were dissatisfied with the cost of health care even though ART is provided free of charge in Tanzania.

Keywords

Patient reported outcomes, Health related quality of life, Care satisfaction, Adherence, HIV, AIDS disease, Viral load, CD4 count.

Materials and Methods

Design and setting of the study

This was a cross sectional study done at Care and Treatment Clinic (CTC) at Muhimbili National Hospital (MNH), Dar es Salaam Tanzania. The HIV clinic at MNH has over 10,000 patients with male to female ratio of 1:1.7. The clinic receives patients referred from district and regional hospital HIV clinics and those referred from the inpatient and outpatient departments of MNH. Patients attend the clinic once in a month, two or three months for clinical evaluation and refill of ART. MNH CTC is a specialized HIV/AIDS Clinic which runs for 5 working days in a week with an average of 90-100 patients being attended daily.

Characteristics of participants

Eligible patients were adults aged 18 years or older attending the clinic for more than six months who were already on ART for at least 6 months. We had no exclusion criteria.

Data collection procedure

MNH CTC was conveniently selected as a study site. Study participants were selected systematically from a list of patients booked to attend the clinic on the days of data collection. From a total of 10,848 patients in the clinic, we wanted 800 patients. We were required to choose every 13th patient, however all the 10,848 patients were not readily available in a single day. As we intended to extend data collection for 3 months to cover all the patients in the clinic, we aimed at interviewing 15 patients a day, making a total of 75 patients a week, 300 patients a month and 900 patients in 3 months. Normally there were on average 60 follow-up patients booked to attend the clinic per day and average of 30 patients who attended as emergency or first-time visitors. So, from these 60 follow up patients, we took every 4th participant aiming at obtaining around 15 patients a day. About fifteen patients were therefore recruited per day on the days of data collection until adequate sample size was reached.

Socio-demographic data were collected using Swahili structured questionnaires.

HRQoL was assessed using a validated face-to-face version of Swahili translated EQ-5D-3L questionnaire [18,19]. EQ-5D-3L measures health on five domains; mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression each with three levels, no problems, some problems and severe problems. Health states were dichotomized into no problems if the score was 1 in all the five dimensions or have problems if the patient reported a problem in any of the five dimensions. Patients who reported presenting with problems or some problems in any of the 5 dimensions were considered having poor HRQoL while those with no problems considered to have good HRQoL [20]. Patients also scored their quality of health on a visual analogue scale (VAS) which ranged from 0% (the worst quality) to 100% (the best quality). Patients with VAS score of 80% or more were considered having good quality of life while those with a score <80% were considered having poor quality of health.

Adherence was assessed retrospectively based on a 7-day recall as used in Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group (AACTG) follow up questionnaire [21]. To assess adherence, respondents were asked to indicate the type of their ART and how many pills they missed in the previous 7 days. Those who could not remember their ART names were shown several ART drugs to identify which ones they used.

Satisfaction was assessed using patient Satisfaction Questionnaire Short-Form (PSQ-18). This is a validated tool that measures satisfaction in the following 7 categories: general satisfaction, technical quality, interpersonal manner, communication, financial aspects of care, time spent with doctors and accessibility of care. A combination of questions in the PSQ-18 were used to specifically assess each of these 7 subscales [22]. PSQ-18 measures satisfaction based on five response on each item; strongly satisfied, satisfied, uncertain, dissatisfied and strongly dissatisfied. PSQ- 18 questionaire was forward translated into Swahili by two of us. To ensure that it maintained its meaning, two independent persons backward-translated it into English and we compared it to the original English questionnaire and discrepancies were discussed and resolved.

Patients’ recent viral loads (VL) were recorded from patients’ records. To be considered recent, VL needed to have been obtained in the past 6 months to the time of data collection. For patients with no recent VL results, we collected 5 ml of blood drawn from the median cubital vein, and kept in K3 EDTA test tubes. Viral load tests were done using nucleic acid amplification polymerase chain reaction by COBAS®AmpliPrep/ COBAS®TaqMan 48 analyzer (Roche Diagnostics) which has a detection limit of 50-10,000,000 copies/ ml. In this study, viral load of <50 copies/ml was defined as undetectable viral load and ≥ 50 copies/ml was defined as detectable viral load.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical clearance was obtained from the MUHAS institution review board. Muhimbili National Hospital gave permission for the study to be conducted in its premises. All participants provided informed consent for participation. Non adherent patients were counselled on medication adherence.

Statistical analysis

Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Science [23]. REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) is a secure, webbased application designed to support data capture for research studies, providing 1) an intuitive interface for validated data entry; 2) audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures; 3) automated export procedures for seamless data downloads to common statistical packages; and 4) procedures for importing data from external sources.

Analysis was done using STATA version 13. HRQoL was analysed as percentage and compared using Chi-square test, whereby patients who reported any problem in the EQ 5D-3L questionnaire had poor HRQoL while those who reported no problem in all the five dimensions of the questionnaire had good HRQoL [20]. Logistic regression was used to assess predictors of poor HRQoL. All variables were first entered singly in the univariate model, then variables with a p-value of 0.25 or less were entered in the multivariable model to control for confounders. Although sex had a p-value greater than 0.25 it was entered into the multivariate model due to its clinical significance [24]. Odds Ratios (OR), 95% Confidence interval and p-values were used to present the logistic regression model results.

Respondent’s adherence level was calculated as the total number of pills the patient swallowed in the previous 7 days divided by the total number of pills needed to be swallowed in 7 days multiplied by 100. Due to high level of reported adherence in the study population, we used 95% as a cut-off point. Participants with adherence level of 95% or more were considered having high adherence while those with adherence level below 95% had low adherence.

Care satisfaction was analysed as percentages of patients who were satisfied with care in the 7 subscales of PSQ-18. Student t-test was used to assess the association of variables with patients’ satisfaction. To assess for internal consistency of the data collected using the Swahili translated PSQ-18, responses were analysed as means (± standard deviations) and Cronbach’s alpha. For all the analyses, P-values <0.05 were considered significant.

Introduction

The use of antiretroviral therapy (ART) has resulted into HIV-infected patients living longer than it was the case in the pre-ART era [1]. Surviving patients are concerned not only with the treatment ability to extend their lives but also that their quality of life is improved on the course [1].

In 2015, there were about 1.4 million people living with HIV in Tanzania [2], 21-30% of them had registered to HIV care and treatment centers (CTC) while 69% of eligible adults were receiving ART [3]. In Tanzania, the cumulative probability of mortality in the first year of ART initiation is high at 10%. However, the mortality is around 3% per year in subsequent years, reflecting on how HIV has been changed into a chronic illness by ART [4].

During HIV chronicity, the core elements of HIV prevention, treatment and support need to be patient centered. The focus should be put on treatment adherence, good communication, ensuring good nutrition, early identification and management of comorbidities, prophylaxis for opportunistic infections, effective referrals to antenatal clinics for Prevention of Mother-To-Child Transmission (PMTCT), family planning services, TB and STI services and other specialized clinics. These patients also need referral to community services such as social welfare and legal support [1,4,5].

Health related quality of life (HRQoL) is a broad concept reflecting a patient’s general subjective perception of the effect of an illness or intervention on physical, psychological and social aspects of their daily lives [6]. Quality of life (QoL) before ART initiation has been reported to be a strong predictor of subsequent QoL after ART initiation [1,6]. Studies have found that predictors for low quality of life in the ART era among HIV infected men were older age, lower socioeconomic status, being widowed and more advanced HIV disease stage 6, while others reported dissatisfaction with the patient-physician relationship [7], depressive symptoms, non-adherence to ART and HIV related stigma [8].

Studies on patient reported outcomes have used validated questionnaires to obtain the intended outcomes. A study in Zimbabwe assessed HRQoL in patients with HIV receiving ART using HIV/AIDStargeted quality of life (HAT-QoL) and EuroQoL Fivedimensions- Three-level (EQ-5D-3L) questionnaires. The patients’ self-reported HRQoL was generally satisfactory in all the HAT-QoL dimensions as well as in two components on the EQ-5D-3L instrument [9].

A study in Sri Lanka using EQ-5D-3L identified that 60% of patients reported being in full health while the percentage of people responding to any problems in the five EQ-5D-3L dimensions increased with age [10]. High levels of depressive symptoms and poor mental health quality of life were found to significantly reduce the probability of ART utilization in another study [11] and poorer QoL [12], thus emphasizing on addressing the psychosocial issues in the management of HIV/ AIDS.

Patients reported outcomes can be coupled with clinical parameters to better inform on patients’ wellbeing. In one study in South Africa, obesity and ART-naivety were identified as predictors for increased mobility problems. Receiving ART was identified as predictor for a higher EQ-5D visual analogue scale (VAS) score [13]. As for self-perceived quality of life, virally suppressed HIV-infected patients have reported low levels of symptoms such as fatigue and energy loss, insomnia, sadness and depression, sexual dysfunction and changes in body appearance [14]. However, when compared to the general population, health-related quality of life scores was significantly lower among HIVinfected patients even when the analysis was restricted to virally suppressed patients who were three quarters of all HIV-infected patients [15].

High levels of adherence to ARVs are necessary for HIV viral suppression, prevention of resistance, and disease progression [16]. On the other hand, non-adherence is associated with lower HRQoL, progression to AIDS and mortality. Self-reported adherence with a mean recall period of seven days is most frequently used although some studies reported thirty days recall period [17]. A Study in Sweden on self-reported adherence, treatment outcome and satisfaction with care using a Nine Item Health Questionnaire in InfCare HIV, showed that patients with adherence of 94% significantly presented with a viral load of less than 50 copies/ml [17].

In Tanzania, very few studies have been done to determine the effect of HIV chronicity on patients’ HRQoL. Therefore, this study investigated HRQoL, ART adherence and care satisfaction as they were reported by HIV-infected patients who were receiving care and treatment in a tertiary National Hospital. This study was conducted from June to December 2017.

Results

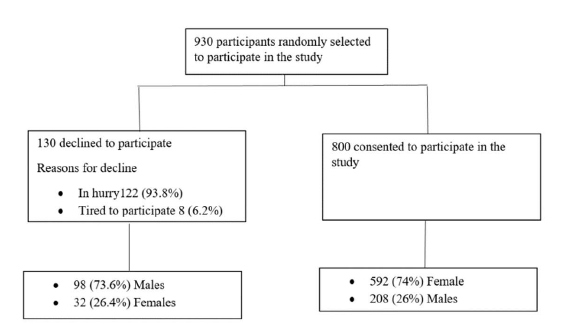

A total of 930 patients were selected, 130 patients declined to participate because they were in a hurry or tired of participating in researches. 800 patients were interviewed as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Patients recruitment flow.

The mean age was 45.7 (± 10.3) years. Majority of the participants were female 592/800 (74%), had attained primary level education 436/800 (54.5%), were married 395/800 (49.4%), and were jobless 222/800 (27.75%). Ninety-five percent (761/800) of the participants were on 1st line ART. HIV viral load was detectable in 210/800 (26.3%), Table 1.

| Characteristics | Frequency (n) | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 208 | 26 |

| Female | 592 | 74 |

| Age (years) | ||

| < 45 | 346 | 43.2 |

| ≥ 45 | 454 | 56.8 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Single | 141 | 17.6 |

| Married | 395 | 49.4 |

| Cohabiting | 40 | 5 |

| Divorced | 76 | 9.5 |

| Widowed | 148 | 18.5 |

| Education Level | ||

| No Formal Education | 47 | 5.9 |

| Primary School | 436 | 54.5 |

| Secondary School | 224 | 28 |

| Vocational | 18 | 2.25 |

| College/ university | 75 | 9.4 |

| Occupation | ||

| Peasants | 76 | 9.5 |

| Civil servants | 180 | 22.5 |

| Private/self employed | 139 | 17.5 |

| Jobless | 222 | 27.7 |

Overall, 606 of the 800 participants (75.75%) reported no problem in all 5 dimensions of EQ-5D-3L. Those who had no problems in mobility were 742 (92.7%), self-care 736 (92%), usual activities 715 (89.4%), pain/discomfort 667 (83.4%) and anxiety/depression 684 (85.5%). Median visual analogue scale (VAS) was 80. Table 2 shows viral load suppression by frequency of reported problems in the EQ-5D-3L. Generally, patients with problems, thence poor quality of life significantly constituted the higher percentage of undetectable viral loads than were patients without problems.

| EQ-5D DIMENSION | Viral load | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Undetectable Number (%) | Detectable Number (%) | Total Number (%) | P-value | ||

| Mobility | No problem | 551(74.3) | 191 (25.7) | 742 (100) | 0.024 |

| Problem | 39 (67.2) | 19 (32.8) | 58 (100) | ||

| Self-care | No problem | 547 (74.3) | 189 (25.6) | 736 (100) | 0.041 |

| Problem | 43 (67.2) | 21 (32.8) | 64 (100) | ||

| Usual activities | No problem | 535 (74.8) | 180 (25.2) | 715 (100) | 0.045 |

| Problem | 55 (64.7) | 30 (35.3) | 85 (100) | ||

| Pain/discomfort | No problem | 502 (75.2) | 165 (24.7) | 667 (100) | 0.029 |

| Problem | 88 (66.2) | 45 (33.8) | 133 (100) | ||

| Anxiety/depression | No problem | 507 (74.1) | 177 (25.9) | 684 (100) | 0.046 |

| Problem | 83 (71.6) | 33 (28.4) | 116 (100) | ||

Most patients (83%) were generally satisfied with care. Mean score for general satisfaction was 3.84 ± 0.77, Cronbach’s alpha =0.72. Satisfaction level was highest in communication (4.28 ± 0.76 Cronbach’s alpha =0.73) and lowest for financial aspects (3.10 ± 0.65 Cronbach’s alpha =0.69). Patients were satisfied with interpersonal manner (mean score 3.92 ± 0 .85 Cronbach’s alpha = 0.75), communication (4.28 ± 0.76 Cronbach’s alpha =0.73) and time spent with the doctor during a visit (mean score 3.46 ± 0.86, Cronbach’s alpha =0.74), Table 3.

| Characteristics | Mean ± SD | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|

| General Satisfaction | 3.84 ± 0.77 | 0.72 |

| Technical quality | 3.88 ± 0 .67 | 0.65 |

| Interpersonal Manner | 3.92 ± 0 .85 | 0.75 |

| Communication | 4.28 ± 0 .76 | 0.73 |

| Time spent with doctor | 3.46 ± 0.86 | 0.74 |

| Accessibility and convenience | 3.64 ± 0.92 | 0.66 |

| Financial aspects | 3.10 ± 0.65 | 0.69 |

| Test scale | 3.73 ± 0.78 | 0.72 |

Predictors of poor HRQoL were dissatisfaction with care, poor adherence to anti-retroviral drugs and detectable viral load. After controlling for other factors, the odds of poor HRQoL were 61% higher in dissatisfied patients compared to those who were satisfied with care, OR (95% CI)=1.61 (1.06-2.43), p=0.025. The odds of poor HRQoL was 58% higher among patients with detectable viral loads compared to those with undetectable viral loads, OR (95% CI)=1.58 (1.10-2.26), p=0.014. Compared to patients with poor adherence to antiretroviral drugs, the odds of poor HRQoL was 55% lower among patients with good adherence to antiretroviral drugs as shown in Table 4.

| Variables | Poor HRQoL Number (%) | Univariate Analysis Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

P-value | Multivariate analysis Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age groups (years) | <45 | 70 (20.8) | 1 | 0.051 | 1 | 0.064 |

| ≥ 45 | 124 (26.8) | 1.40 (0.99-1.95) | 1.37 (0.98-1.96) | |||

| Sex | Female | 138 (23.3) | 1 | 0.296 | 1 | 0.387 |

| Male | 56 (26.9) | 1.21 (0.85-1.74) | 1.18 (0.81-1.72) | |||

| Education | Informal | 18 (38.3) | 1 | 0.023 | 1 | 0.066 |

| Formal | 176 (23.4) | 0.49 (0.27-0.91) | 0.55 (0.29-1.04) | |||

| Marital status | Single | 33 (23.4) | 1 | 0.796 | - | - |

| Ever married | 161 (24.4) | 1.06 (0.69 -1.62) | - | |||

| ART regimen |

1st line | 180 (23.7) | 1 | 0.086 | 1 | 0.104 |

| 2nd line | 14 (35.9) | 1.80 (0.92-3.55) | 1.78 (0.89-3.55) | |||

| Viral load | Undetectable | 128 (21.7) | 1 | 0.004 | 1 | 0.014 |

| Detectable | 66 (31.43) | 1.65 (1.16-2.35) | 1.58 (1.10-2.26) | |||

| General Satisfaction | Satisfied | 149 (22.4) | 1 | 0.009 | 1 | 0.025 |

| Dissatisfied | 45 (33.1) | 1.7 (1.15-2.55) | 1.61 (1.06-2.43) | |||

| Adherence | Good | 151 (21.8) | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Poor | 43 (39.8) | 0.42 (0.28-0.65) | 0.45 (0.29-0.70) | |||

Discussion

Majority of study participants were female comprising 74%, depicting the fact that in Tanzania, the prevalence of HIV is higher among females than males [3]. But again, women have high health seeking behaviour than men [3] so are likely to enrol to clinics in large numbers than men. In the present study, female to male ratio was 3:1 which seems to differ from National AIDS Control Programme (NACP) data which reports 2:1 for females and males respectively [5]. This difference in sex ratio could be explained by the fact that males constituted 3/4 of those who declined to participate in the present study.

Majority of the study participants were in the age group of 30 to 59 years, reflecting the National data on HIV which indicated that majority of HIV individuals were in the age group 15 to 49 [3]. Majority of the participants were jobless, a proxy indicator for poor socioeconomic status which is a known risk factor for HIV acquisition [25,26].

HIV viral loads were detectable in more than a quarter of the patients even though majority (86.6%) reported good adherence to ART. Adherence was assessed based on self-reporting, which is subject to memory recall bias, particularly so in people with low literacy. Kalichman et al, in their review on adherence to combination antiretroviral therapies in HIV patients of low health literacy found that; self-reported adherence is subject to memory errors, perhaps even more so in people with poor literacy [27]. This finding probably informs on considering, using reported adherence in combination with other means of adherence determination [28].

Majority of study participants had good HRQoL after reporting no problems across all five dimensions of EQ- 5D-3L. Problems in all domains were found to be higher in participants above 60 years. This concurred with a study by Liu et al. which showed advanced age to be a predictor of lower quality of life [6]. Likewise, using the VAS for measuring quality of life, generally patients at MNH reported good quality of life with a median VAS score of 80. This finding is similar to the finding of a study done in Zimbabwe by Mafirakureva et al. which reported median VAS of 79 [9]. Level of education and detectable viral load predicted poor HRQoL. This confirms the reported hypothesis that detectable viral load is associated with lower quality of life [6,8,16].

In this study, most patients were generally satisfied with care. Particularly patients were satisfied with interpersonal manner, time spent with the doctor and communication. Patients had low satisfaction scores in the financial domain which can be explained by the fact that patients had to pay for investigations including full blood picture, renal and liver function tests although they received ART free of charge. Patients in our study had higher scores in all subscales of satisfaction when compared to a study in India by Chander et al. who used PSQ-18 [29] but lower scores than those in a study by Vahab et al. [30]. This implies moderate satisfaction in our study with respect to the two studies above. Patient satisfaction has direct effects on retention in HIV care and adherence to ART [31].

Nearly 90% of participants in this study reported high adherence to ART of more than 95%. This finding is in concordance to a meta-analysis of studies on ART adherence by Mills et al. who found that 77% of patients in Africa achieved adequate adherence of 95% compared to just 55% of patients in North America [32]. Other studies also showed good rates of adherence to ARV in this setting [33]. However, more than a quarter of participants in the present study had detectable viral loads. This raise a question on whether the detectable viral loads are attributable to the fact that 7 days adherence recall might not represent long term adherence status of patients or attributable to other factors like malabsorption. This is an area for investigation.

Predictors of poor HRQoL in the present study were dissatisfaction with care, poor adherence to antiretroviral drugs and detectable viral load. Good HRQoL has been reported to depend on good adherence [8] and care satisfaction [34], both of which have impact on viral load suppression.

Conclusions

Health related quality of life, care satisfaction and adherence to antiretroviral therapy are patient reported outcomes which informed the general wellbeing of the participants at MNH CTC. Generally, patients had presented with good quality of life and adherence to medication. However, the participants were generally not satisfied with care owing to financial aspects of care. More than a quarter of participants had detectable viral loads, calling for further investigation on why detectable viral loads amid high adherence in most of the patients.

Competing Interests

Authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding

We acknowledge the Muhimbili National Hospital Research, Teaching and Consultancy unit and HIV Implementation Science (HIS) project of the Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences under Fogarty International, of the U.S.A National Institutes of Health (NIH) in collaboration with T. Chan Harvard School of Public Health for funding this study.

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge Prof. Ferdinand Mugusi for guidance on the methods, Dr. Bruno Mbando and Ms Oliva Safari for their contribution and guidance in data analysis, all the staff members of the MNH clinic for their support during data collection, Dr. Athumani Ramadhan and Dr. Martha Nkya for the actual data collection, and lastly but not least, we would like to thank all the patients who participated in this study.

Author’s Contribution

EO and GAS designed the study. EO did data collection. JR, GAS supervised and guided the process of data collection and analysis. RS and GAS did analyze the data. GAS drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript for publication.

References

2. UNAIDS. Global AIDS Update. UNAIDS. 2016;17 Suppl 4:S3-11. Available from https://www.unaids. org/en/resources/documents/2016/Global-AIDSupdate-2016

3. Tanzania Commision for AIDS (TACAIDS). HIV/AIDS and Malaria Indicator Survey 2011–12. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania 2013;103–10. Available from https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/AIS11/AIS11.pdf

4. Tanzania Ministry of Health and Social Welfare. HIV / AIDS / STI Surveillance Report Report Number 22 [Internet]. 2011. Available from: www.nacp.go.tz/site/download/report22.pdf

5. Tanzania National Control Program. National guidelines for the management of HIV. 2015. Available from https:/aidsfree.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/04_11_2016. tanzania_national_guideline_for_management_hiv_and_aids_may_2015._tagged.pdf

6. Liu C, Weber K, Robison E, Hu Z, Jacobson LP, Gange SJ. Assessing the effect of HAART on change in quality of life among HIV-infected women. AIDS research and therapy. 2006 Dec;3(1):6.

7. Detmar SB, Muller MJ, Schornagel JH, Wever LD V, Aaronson NK. Health-related quality-of-life assessments and patient-physician communication: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2002;288(23):3027–34.

8. Ammassari A, Murri R, Pezzotti P, Trotta MP, Ravasio L, De PL, Lo SC, Narciso P, Pauluzzi S, Carosi G, Nappa S. Self-reported symptoms and medication side effects influence adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy in persons with HIV infection. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2001 Dec;28(5):445-9.

9. Mafirakureva N, Dzingirai B, Postma MJ, van Hulst M, Khoza S. Health-related quality of life in HIV/AIDS patients on antiretroviral therapy at a tertiary care facility in Zimbabwe. AIDS Care. 2016;28(7):904–12.

10. Kularatna S, Whitty JA, Johnson NW, Jayasinghe R, Scuffham PA. EQ-5D-3L derived population norms for health related quality of life in Sri Lanka. PLoS One.2014;9(11):1–12.

11. Cook JA, Cohen MH, Burke J, Grey D, Anastos K,Kirstein L, Palacio H, Richardson J, Wilson T, Young M. Effects of depressive symptoms and mental health quality of life on use of highly active antiretroviral therapy among HIV-seropositive women. JAIDSHAGERSTOWN MD-. 2002 Aug 1;30(4):401-9.

12. Talukdar A, Ghosal MK, Sanyal D, Talukdar PS, Guha P, Guha SK, Basu S. Determinants of quality of life in HIV-infected patients receiving highly active antiretroviral treatment at a medical college ART center in Kolkata, India. Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care (JIAPAC). 2013 Jul;12(4):284-90.

13. Nglazi MD, West SJ, Dave JA, Levitt NS, Lambert EV. Quality of life in individuals living with HIV / AIDS attending a public sector antiretroviral service in. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:676.

14. Erdbeer G, Sabranski M, Sonntag I, Stoehr A, Horst HA, Plettenberg A, Schewe K, Unger S, Stellbrink HJ, Fenske S, Hoffmann C. Everything fine so far? Physical and mental health in HIV-infected patients with virological success and long-term exposure to antiretroviral therapy. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2014 Nov;17:19673.

15. Miners A, Phillips A, Kreif N, Rodger A, Speakman A, Fisher M, Anderson J, Collins S, Hart G, Sherr L, Lampe FC. Health-related quality-of-life of people with HIV in the era of combination antiretroviral treatment: a crosssectional comparison with the general population. The lancet HIV. 2014 Oct 1;1(1):e32-40.

16. Achappa B, Madi D, Bhaskaran U, Ramapuram JT, Rao S, Mahalingam S. Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy Among People Living with HIV. North American Journal of Medical Sciences. 2013 Mar;5(3):220–3.

17. Marrone G, Mellgren A, Eriksson LE, Svedhem V.High concordance between self-reported adherence, treatment outcome and satisfaction with care using a nine-item health questionnaire in infcareHIV. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0156916.

18. The EuroQol Group. EuroQol: A new facility for the measurement of health related quality of life. Health Policy (New York). 1990;16(16):199–208.

19. Rabin R, Gudex C, Selai C, Herdman M. From translation to version management: A history and review of methods for the cultural adaptation of the euroqol five-dimensional questionnaire. Value Health. 2014;17(1):70–6.

20. EuroQol Research Foundation. EQ-5D-3L User Guide 2018. Available from: www.euroqol.org/ publications/user-guides

21. Chesney MA, Ickovics JR, Chambers DB, Gifford AL, Neidig J, Zwickl B, Wu AW, Patient Care Committee & Adherence Working Group of the Outcomes Committee of the Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group (AACTG). Selfreported adherence to antiretroviral medications among participants in HIV clinical trials: the AACTG adherence instruments. AIDS care. 2000 Jun 1;12(3):255-66.

22. Marshall GN, Hays RD. The Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire Short Form (PSQ-18). Rand. 1994. Available from https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/papers/2006/P7865.pdf

23. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) - A meta data driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatict support. J Biomedical Information. 2009;42(2):377–81.

24. Bursac Z, Gauss CH, Williams DK, Hosmer DW.Purposeful selection of variables in logistic regression. Source Code for Biology Medicine. 2008;3:1–8.

25. Adeyemi M. Relationship between socioeconomic status and HIV infection in a rural tertiary health center. HIV/AIDS Research and Palliative Care. 2014;6(23 April):61–7.

26. Bunyasi EW, Coetzee DJ. Relationship between socioeconomic status and HIV infection: Findings from a survey in the Free State and Western Cape Provinces of South Africa. British Medical Journal. 2017;7:e016232.

27. Kalichman SC, Ramachandran B, Catz S. Adherence to combination antiretroviral therapies in HIV patients of low health literacy. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1999;14(5):267–73.

28. Sangeda RZ, Mosha F, Prosperi M, Aboud S, Vercauteren J, Camacho RJ, et al. Pharmacy refill adherence outperforms self-reported methods in predicting HIV therapy outcome in resource-limited settings. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):1–11.

29. Chander V, Bhardwaj AK, Raina SK, Bansal P, Agnihotri RK. Scoring the medical outcomes among HIV / AIDS patients attending antiretroviral therapy center at Zonal Hospital, Hamirpur, using Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire (PSQ-18). Indian Journal of Sexually Transmitted Diseases and AIDS. 2011;32(1):19–22.

30. Vahab SA, Madi D, Ramapuram J, Bhaskaran U, Achappa B. Level of Satisfaction Among People Living with HIV (PLHIV) Attending the HIV Clinic of Tertiary Care Center in Southern India. Journal of Clinical Diagnosis Research. 2016 Apr;10(4):OC08-OC10.

31. Sherbourne CD, Hays RD, Ordway L, DiMatteo MR, Kravitz RL. Antecedents of adherence to medical recommendations: Results from the medical outcomes study. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1992;15(5):447–68.

32. Mills EJ, Nachega JB, Buchan I, Orbinski J, Attaran A, Singh S, Rachlis B, Wu P, Cooper C, Thabane L, Wilson K. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa and North America: a meta-analysis. Jama. 2006 Aug 9;296(6):679-90.

33. Sangeda RZ, Mosha F, Aboud S, Kamuhabwa A, Chalamilla G, Vercauteren J, Van Wijngaerden E, Lyamuya EF, Vandamme AM. Predictors of non adherence to antiretroviral therapy at an urban HiV care and treatment center in Tanzania. Drug, healthcare and patient safety. 2018;10:79.

34. de Boer J, van Dam F, Sprangers M. Health-related quality-of-life evaluation in HIV-infected patients . A review of the literature . Pharmacoeconomics. 1995;8(4):291–304.