Abstract

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy has revolutionized the management of refractory hematologic malignancies such as leukemia, lymphoma and multiple myeloma, offering unprecedented remission rates. Yet, complications arising from infections remain a major challenge, particularly in the early post-infusion period and during prolonged immune suppression. This editorial synthesizes recent evidence (2021–2025) on infection epidemiology, risk factors, and stewardship strategies in CAR T-cell recipients. Early infections, especially from bacteria are influenced by neutropenia, prior therapy, and disease biology, while long-term immune suppression of CD4+ T cells help sustain vulnerability. Antibiotic stewardship presents a critical opportunity to reduce unnecessary exposure through biomarker-guided diagnostics and de-escalation protocols. Rising cases of antimicrobial resistance and dysbiosis pose significant challenges, while emerging diagnostic technologies and microbiome-focused interventions offer promise. Future strategies should be focused on integrating clinical vigilance, harmonized prophylaxis, and microbiome-awareness stewardship to optimize both safety and efficacy in CAR T-cell therapy.

Introduction

Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-cell (CAR T-cell) therapy, an innovative form of immunotherapy is becoming the cornerstone of treatment for patients with relapsed and refractory hematologic malignancies such as leukemia, lymphoma, and multiple myeloma [1]. Despite the promises recorded, factors such as early infusion fevers, overlapping inflammatory toxicities and prolonged immune deficits threaten their continued use for treatment [2]. At the end, the physician is faced with a decision; to treat the malignancy (protect the patient) or deal with the consequences of the treatment: confront the case of antimicrobial resistance and microbiome disruption created by the treatment.

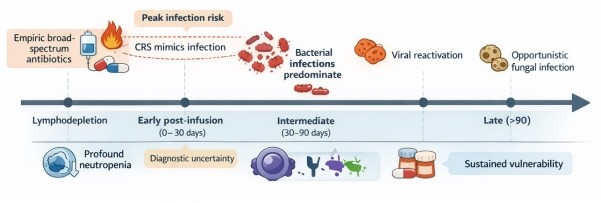

Early Infectious Complications

The first month after CAR T-cells infusion is the period most frequently associated with infections (Figure 1). In their work, Wittmann Dayagi et al. [3] documented 36 infections out of 88 patients treated with CD28-based CD19 CAR T-cells. Reduced neutrophil count (Neutropenia) and lack of response were cited as major risk factors associated with CAR T-cell treatment. Similarly, Mikkilineni et al. [4] reported that, 32.7% of patients across five trial studies developed infections within 30 days, with bacteremia and bacterial site infections predominating as potential risk factors. The study of Beyar-Katz et al. [5] also observed infections in 45% of the patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, while Garcia-Pouton et al. [6] documented 77 infections among 91 adults. Chimeric Release Syndrome resulting from rapid and massive activation of immune cells has been reported to complicate diagnosis, yet studies by Ng et al . [7] reports that despite the low bacteremia (2.7%) and CRS recorded among patients, they were still given empiric antibiotics. Based on these observations, it has been suggested that biomarkers including C-Reactive Protein (CRP), D-dimer, and ferritin could offer moderate level of discrimination beyond 14 days for monitoring infection and inflammation.

Long-Term Immune Deficiency

Immune suppression has been reported to persist beyond the acute phase. In their study, Cheng et al. [8] demonstrated that patients with multiple myeloma that received CAR T-cell infusion experienced prolonged CD4+ T-cell deficiency and late infections, particularly in bacteremia. In another study, Portuguese et al. [9] showed that, extramedullary disease (EMD) was linked to higher toxicity, prolonged neutropenia, increased bacteremia, and worse survival while Masih et al. [10] reported on the convergence of serious bacterial infections with HLH-like CRS in pediatric patients, underscoring the complexity of overlapping toxicities.

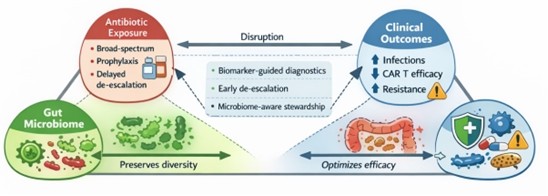

Antibiotic Stewardship (Figure 2)

Patients on CAR T-cell therapy are vulnerable to immune suppression and infection, often necessitating antibiotic use. In their review of continuous versus intermittent beta-lactam infusion, Alawyia et al. [11], reported the benefits of extended infusion in sepsis and Febrile Neutropenia (FN) with Mizuno et al. [12] emphasizing adherence to febrile neutropenia (FN) guidelines for better outcome. On the contrary, Lucena et al., [13] reported that cutting back on the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics reduces unnecessary exposure without compromising clinical outcomes. Additionally, studies by Malard and Mohty [14] argued that the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics may impair the efficacy of CAR T-cell therapy, due to the ability of the drugs to disrupt the gut microbiome. Therefore, for effective outcome, only clinically stable patients should be recommended for CAR T-cell therapy while patients already receiving treatment should be managed to mitigate risk of infection [15,16].

Antimicrobial Resistance

The rise in number of antibiotic resistances especially, Extended Spectrum Beta-Lactamase (ESBL) producing and carbapenem resistant gram-negative bacteria, poses a serious global threat to wellbeing of individuals [17]. Fluoroquinolone prophylaxis has been proven to reduce bloodstream infections in immunocompromised patients such as those on CAR T-cell therapy. However, their continuous use increases the risk of resistance, with experts suggesting the selective use of the treatment based on individual assessment. Consequently, Kampouri et al. [18] calls for a harmonized practice involving variation in the use of antibiotics and monitoring across centers.

Microbiome and Diagnostics

Microbiome dysregulation is implicated as a risk factor in CAR T-cell therapy. The presence of gut dominant bacteria such as Lactobacillus rhamnosus in the bloodstream indicates their potential role in infection risk [19]. CAR T-cell manufacturing process has also been implicated as a source of infection risk, with a study by Ayala et al. [20] reporting rapid detection of microbial contaminants during CAR T-cell manufacturing. Therefore, experts advise that infection prevention is key to optimizing CAR T cell therapy outcomes. Emerging microbiome focused trials suggest that antibiotic disruption of the microbiome impairs immune recovery and efficacy of CAR T cell therapy.

Future Directions

Novel CAR T cell therapies targeting antigens beyond CD19, B-cell malignancies and natural killer (NK)-based-therapies, offer new treatment options for the management of refractory malignant cancers due to their ability to affect the immune system differently and potentially introduce new risks of infection [21,22]. To that end, the European Society of Blood and Marrow Transplant (EBMT) recommends the harmonization of supportive care, with precision medicine approach promising a refined stewardship and infection prevention [23].

Conclusion

Infections are a frequent ongoing concern after CAR T cell therapy that are influenced by patients’ health status, immune recovery and how antibiotic are used by the patient. Antibiotics use should be highly regulated to avoid risk of resistance development by the organism and protect the gut microbiome. Future strategies including integration of biomarker-guided diagnostics to detect infections more precisely, harmonized prophylaxis (standardized preventive treatments), and microbiome-awareness to protect and preserve beneficial bacteria, thereby optimizing both safety and efficacy.

References

2. Wu D, Xu-Monette ZY, Zhou J, Yang K, Wang X, Fan Y, et al. CAR T-cell therapy in autoimmune diseases: a promising frontier on the horizon. Front Immunol. 2025 Aug 12;16:1613878.

3. Wittmann Dayagi T, Sherman G, Bielorai B, Adam E, Besser MJ, Shimoni A, et al. Characteristics and risk factors of infections following CD28-based CD19 CAR-T cells. Leuk Lymphoma. 2021 Jul;62(7):1692–701.

4. Mikkilineni L, Yates B, Steinberg SM, Shahani SA, Molina JC, Palmore T, et al. Infectious complications of CAR T-cell therapy across novel antigen targets in the first 30 days. Blood Adv. 2021 Dec 14;5(23):5312–22.

5. Beyar-Katz O, Kikozashvili N, Bar On Y, Amit O, Perry C, Avivi I, et al. Characteristics and recognition of early infections in patients treated with commercial anti-CD19 CAR-T cells. Eur J Haematol. 2022 Jan;108(1):52–60.

6. Garcia-Pouton N, Ortiz-Maldonado V, Peyrony O, Chumbita M, Aiello TF, Monzo-Gallo P, et al. Infection epidemiology in relation to different therapy phases in patients with haematological malignancies receiving CAR T-cell therapy. Eur J Haematol. 2024 Mar;112(3):371–8.

7. Ng SK, Flaherty PW, Ancheta M, Tindbaek KA, Sekhon MK, Huang JJ, et al. Opportunities to Improve Antibiotic Stewardship, and Identification of Blood Biomarkers Associated with Bacteremia Following CAR-T Cell Therapy. Transplant Cell Ther. 2025 Oct;31(10):838.e1–16.

8. Cheng H, Ji S, Wang J, Hua T, Chen Z, Liu J, et al. Long-term analysis of cellular immunity in patients with RRMM treated with CAR-T cell therapy. Clin Exp Med. 2023 Dec;23(8):5241–54.

9. Portuguese AJ, Liang EC, Huang JJ, Jeon Y, Dima D, Banerjee R, et al. Extramedullary disease is associated with severe toxicities following B-cell maturation antigen CAR T-cell therapy in multiple myeloma. Haematologica. 2025 Dec 1;110(12):3065–77.

10. Masih KE, Ligon JA, Yates B, Shalabi H, Little L, Islam Z, et al. Consequences of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis-like cytokine release syndrome toxicities and concurrent bacteremia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2021 Oct;68(10):e29247.

11. Alawyia B, Fathima S, Spernovasilis N, Alon-Ellenbogen D. Continuous versus intermittent infusion of beta-lactam antibiotics: where do we stand today? A narrative review. Germs. 2024 Jun 30;14(2):162–78.

12. Mizuno K, Inose R, Goto R, Muraki Y. Adherence to guidelines for antibiotics used in the initial treatment of febrile neutropenia in patients with cancer: a study using health insurance claims database in Japan. J Pharm Health Care Sci. 2025 Jun 6;11(1):47.

13. Lucena M, Gaffney KJ, Urban T, Forbes C, Srinivas P, Majhail NS, et al. Early de-escalation of antibiotic therapy in hospitalized cellular therapy adult patients with febrile neutropenia. Clin Hematol Int. 2024 Feb 22;6(1):59–66.

14. Malard F, Mohty M. Antibiotics: bad bugs for CAR-T cells? Blood. 2025 Feb 20;145(8):787–8.

15. Tabbara N, Dioverti-Prono MV, Jain T. Mitigating and managing infection risk in adults treated with CAR T-cell therapy. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2024 Dec 6;2024(1):116–25.

16. Baden LR, Swaminathan S, Almyroudis NG, Angarone M, Baluch A, Barros N, et al. Prevention and Treatment of Cancer-Related Infections, Version 3.2024, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2024 Nov;22(9):617–44.

17. Baccelli F, Aguilar-Guisado M, Vidal CG, Mikulska M, Vanbiervliet Y, Blijlevens N, et al. Epidemiology of resistant bacterial infections in patients with hematological malignancies or undergoing hematopoietic cell transplantation in Europe: A systematic review by the European Conference on Infections in Leukemia (ECIL). J Infect. 2025 Sep;91(3):106571.

18. Kampouri E, Little JS, Rejeski K, Manuel O, Hammond SP, Hill JA. Infections after chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T-cell therapy for hematologic malignancies. Transpl Infect Dis. 2023 Nov;25 Suppl 1:e14157.

19. Mannavola CM, De Maio F, Marra J, Fiori B, Santarelli G, Posteraro B, et al. Bloodstream infection by Lactobacillus rhamnosus in a haematology patient: why metagenomics can make the difference. Gut Pathog. 2025 Jun 21;17(1):47.

20. Ayala Ceja M, Khericha M, Harris CM, Puig-Saus C, Chen YY. CAR-T cell manufacturing: Major process parameters and next-generation strategies. J Exp Med. 2024 Feb 5;221(2):e20230903.

21. Cao LY, Zhao Y, Chen Y, Ma P, Xie JC, Pan XM, et al. CAR-T cell therapy clinical trials: global progress, challenges, and future directions from ClinicalTrials.gov insights. Front Immunol. 2025 May 20;16:1583116.

22. Lin C, Horwitz ME, Rein LAM. Leveraging Natural Killer Cell Innate Immunity against Hematologic Malignancies: From Stem Cell Transplant to Adoptive Transfer and Beyond. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Dec 22;24(1):204.

23. Greco R, Ruggeri A, McLornan DP, Snowden JA, Alexander T, Angelucci E, et al. Indications for haematopoietic cell transplantation and CAR-T for haematological diseases, solid tumours and immune disorders: 2025 EBMT practice recommendations. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2025 Nov;60(11):1499–525.