Abstract

Background: Substance Use Disorder (SUD) is common among patients admitted to the hospital, with particularly high rates among those hospitalized for trauma. It is important to further understand the clinical outcomes of trauma patients with SUD, a key metric for which is hospital length of stay (LOS). There is little existing evidence on the relationship between SUD and LOS in trauma patients. We investigated the impact of pre-existing SUD on hospital LOS in admitted trauma patients.

Methods: We performed a retrospective analysis on trauma patients admitted to our Level I Trauma Center between January 2021 and August 2023. Patients were categorized into two major groups: those with and without a history of SUD based on diagnoses in their electronic health records. Descriptive and regression analyses were performed to estimate the effect of SUD on hospital LOS.

Results: The study comprised 2,994 trauma patients aged 18 or older. 37.9% had documented SUD. Patients with SUD were younger (mean age 40.88 vs. 58.99 years, p<.001) and predominantly male (72.9% vs. 53.3%, p<.001). SUD patients had a higher mean ISS score and higher rates of alcohol use disorder, bipolar disorder, and smoking, whereas non-SUD patients had higher rates of diabetes mellitus and hypertension. There was no statistically significant difference in mean LOS (p=.51) and mean ICU days(p=.95) between the two groups. On multivariable regression analysis, age and ISS (moderate and severe) were statistically significant predictors of LOS, and SUD's impact on LOS was not statistically significant (B=0.516, p=.056).

Conclusion: Although SUD does not appear to have a clear relationship with LOS in trauma patients, it is linked to several factors that complicate management. A multidisciplinary approach to these challenges may improve outcomes.

Keywords

Substance use disorder,Trauma, Mortality, Length of stay, Injury severity score, Age, Substance use

Introduction

Substance Use Disorder (SUD) is a multifactorial disorder characterized by use of substances such as illegal/legal drugs, alcohol, or medications [1]. SUD is prevalent among patients admitted to the hospital, with high rates among patients hospitalized for trauma [2]. Injury risk and severity increase in a dose-dependent fashion with blood alcohol content as well as with other substances [3]. During the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic, it was found that trauma centers were admitting significantly more trauma patients with a history of SUD [4], further highlighting the importance of understanding the relationship between SUD and trauma. While the association between substance/alcohol use and traumatic injuries has been thoroughly explored, little is understood about how a history of SUD may impact the in-patient care of trauma patients.

Length of stay (LOS) is an important metric for assessing the in-patient experience of trauma patients. Previous studies have found that the risk of adverse health events, such as drug reactions, infections, and ulcers is higher among patients with longer LOS [5]. Beyond adverse health effects, increased LOS also presents an increased financial burden on patients and their families [6]. LOS is affected by many factors, one of which may be prior history of SUD. It has been shown that pre-existing substance-use is associated with a longer hospital LOS in some patient populations [7]. However, there is little existing evidence on the relationship between SUD and LOS.

This study investigates the impact of pre-existing SUD on hospital length of stay in trauma patients at our level-1 trauma center. LOS serves as an indicator for assessing the efficacy of treatment interventions and potential complications. Understanding the relationship between previous or current substance use and post-admission variables such as LOS is essential in providing high-quality patient care and facilitating a multidisciplinary treatment plan to improve patient outcomes.

Methods and Materials

This was a retrospective study with secondary analysis of existing medical records at our university affiliated Level 1 trauma center. All data was acquired from the trauma surgery and emergency department registries.The trauma registry was used to identify adult trauma patients at our center. Trauma patients admitted to our center from January 2021 to August 2023 were reviewed. There were 2,994 patients total, with 1,136 in the SUD group and 1,858 in the non-SUD group. Patients were included if they were aged 18 or above. Patients who were intubated and/or had a GCS score <8 were excluded from the study. In addition, trauma patients who were not admitted to the hospital were excluded.

Several demographic variables were collected including: gender, age, and comorbidities. We additionally collected information on pre- and post-admission variables, including Injury Severity Score (ISS), injury type, ETOH level, toxicology screen, Glasgow Coma Scale score, operative intervention status, hospital length of stay (LOS), days spent in the ICU, and discharge disposition. Patients were categorized into two major groups for analysis: those with history of SUD versus patients without history of SUD based on the diagnoses documented in their electronic health record.

Variables were analyzed in each group, along with history of SUD, to estimate their effect on the primary endpoint in our study: length of stay. Descriptive analysis of the patient demographic, pre and post admission variables, and length of stay was performed. Multivariable regression analysis was conducted to evaluate the relationship between independent variables and the primary endpoint, length of stay (LOS). Only variables that showed statistically significant differences between groups in the descriptive analysis were included in the multivariable analysis. The unstandardized coefficient (B) represents the actual change in the dependent variable (LOS) for each unit change in the independent variable, without standardizing for different units of measurement. In contrast, the standardized coefficient (Beta) reflects the strength and direction of the relationship between the independent variable and the dependent variable on a comparable scale (i.e., standardized units), allowing for direct comparison across different variables.

Results

Descriptive analysis

Descriptive analyses of demographic data and pre- and post-admission were performed (Table 1). The mean age for patients with SUD was substantially and statistically significantly lower (M=40.88, SD=14.81) compared to those without SUD (M=58.99, SD=21.53) (p<.001). Gender distribution also differed significantly between the groups, with a higher proportion of males in the SUD group (72.9%) compared to the non-SUD group (53.3%) (p<.001).

|

Variable |

SUD Group N=1,136 (37.9%) |

Non-SUD Group N=1,858 (62.1%) |

p-value |

|

Age Mean, SD |

M=40.88, SD=14.81 |

M=58.99, SD=21.53 |

<.001 |

|

Gender (n, %) Male Female |

Male=829 (72.9%) Female=307 (27.1%) |

Male=992 (53.3%) Female=866 (46.7%) |

<.001 |

|

Comorbidities (n) Alcohol Use Disorder Bipolar I/II Current Smoker Diabetes Mellitus Hypertension Major Depressive Disorder Other Mental/Personality Disorders |

234 (20.6%) 39 (3.4%) 666 (58.62%) 74 (6.5%) 195 (17.2%) 65 (5.7%) 439 (38.6%) |

160 (8.6%) 13 (0.7%) 429 (23.1%) 336 (18.1%) 820 (44.1%) 73 (3.9%) 493 (26.5%) |

<.001 <.001 <.001 <.001 <.001 .02 .01 |

|

ISS (n, %) ≤9(mild) 10–24 (moderate) ≥25 (severe) |

Mild=699 (61.5%) Moderate=388 (34.2%) Severe=49 (4.3%) |

Mild=1301 (70.0%) Moderate=504 (27.1%) Severe=53 (2.9%) |

<.001 <.001 .04 |

|

GCS (mean ± SD) |

M=14.84, SD=0.6 |

M=14.85, SD=0.58 |

.30 |

|

Injury Type (n, %) Blunt Burn Penetrating |

835 (73.5%) 70 (6.2%) 229 (20.2%) |

1,575 (84.7%) 139 (7.5%) 144 (7.7%) |

<.001 .17 <.001 |

|

Tox Screen (n) Benzodiazepines Cannabis Barbiturates Opiates Amphetamine Cocaine Methamphetamine |

44 (3.9%) 595 (52.4%) 3 (0.3%) 32 (2.8%) 100 (8.8%) 200 (17.6%) 1 (0.1%) |

15 (0.8%) 79 (4.3%) 2 (0.1%) 13 (0.7%) 10 (0.5%) 10 (0.5%) 0 (0.0%) |

<.001 <.001 .31 <.001 <.001 <.001 .20 |

|

Operation (n, %) Yes No |

724 (63.7%) 412 (36.3%) |

1,051 (56.5%) 807 (43.4%) |

<.001

|

|

Hospital LOS (mean ± SD) |

M=5.74, SD=7.05 |

M=5.90, SD=5.79 |

.51 |

|

ICU days (n, mean ± SD) |

N =141, M=5.66, S =5.81 |

N=208, M=5.62, SD=4.91 |

.95 |

|

Complications (n) Alcohol Withdrawal Syndrome Surgical Site Infection Venous Thromboembolic Event Pressure Ulcer Unplanned return to OR Unplanned admission to ICU Unplanned intubation Myocardial Infarction Pneumonia Acute Kidney Injury/Insufficiency Severe Sepsis Catheter Associated UTI Stroke/CVA Cardiac Arrest with CPR |

30 (2.6%) 8 (0.7%) 6 (0.5%) 1 (0.1%) 7 (0.6%) 14 (1.2%) 3 (0.3%) 1 (0.1%) 4 (0.4%) 6 (0.5%) 2 (0.2%) 0 (0.0%) 2 (0.2%) 0 (0.0%) |

28 (1.5%) 5 (0.3%) 17 (0.9%) 12 (0.6%) 10 (0.5%) 20 (1.1%) 3 (0.2%) 6 0.3%) 3 (0.2%) 2 (0.1%) 1 (0.1%) 2 (0.1%) 4 (0.2%) 2 (0.1%) |

.03 .08 .30 .02 .63 .70 .54 .20 .62 .03 .30 .27 .82 .27 |

|

DC Disposition (n, %) Home (with self-care or services) Death Acute Care Facility Inpatient Rehab Skilled Nursing Facility/Home Long Term Care Hospice Left AMA Mental Health/Psychiatric Hospital Correctional Facility/Court |

937 (82.3%) 3 (0.3%) 8 (0.7%) 96 (8.5%) 2 (0.2%) 1 (0.1%) 2 (0.2%) 42 (3.8%) 30 (2.6%) 15 (1.3%) |

1221 (65.7%) 22 (1.2%) 5 (0.3%) 489 (26.3%) 42 (2.3%) 3 (0.2%) 24 (1.3%) 28 (1.5%) 12 (0.6%) 12 (0.6%) |

<.001 .007 .08 <.001 <.001 .59 .001 <.001 <.001 .06 |

The prevalence of several comorbidities was statistically significantly different between the two groups. Patients with SUD had higher rates of alcohol use disorder (20.6% vs. 8.6%, p<.001), bipolar disorder (3.4% vs. 0.7%, p<.001), and smoking (58.62% vs. 23.1%, p<.001). Conversely, conditions such as diabetes mellitus (6.5% vs. 18.1%, p<.001) and hypertension (17.2% vs. 44.1%, p<.001) were more common in the non-SUD group. Other mental/personality disorders were also more prevalent in the SUD group (38.6% vs. 26.5%, p=.01), while dementia was more common in the non-SUD group (0.35% vs. 6.5%, p<.001).

Injury Severity Score (ISS) differed significantly, with the SUD group having a higher proportion of severe injuries (ISS≥25: 4.3% vs. 2.9%, p=.04). The types of injuries also varied; blunt injuries were more common in the non-SUD group (84.7% vs. 73.5%, p<.001), while penetrating injuries were more frequent in the SUD group (20.2% vs. 7.7%, p<.001).

Positive toxicology screens for substances such as benzodiazepines, cannabis, opiates, amphetamines, and cocaine were statistically significantly higher in the SUD group (all ps<.001). The mean ETOH level did not significantly differ between the groups (p=.56). The SUD group had a statistically significantly higher proportion of operations (63.7% vs. 56.5%, p<.001). Notably, length of hospital stay (LOS) and ICU days did not statistically significantly differ between the groups.

Alcohol withdrawal syndrome was statistically significantly more common in the SUD group (2.6% vs. 1.5%, p=.03), while surgical site infections and venous thromboembolic events showed no statistically significant differences. Discharge dispositions revealed statistically significant differences; a higher percentage of SUD patients were discharged home (82.3% vs. 65.7%, p<.001), whereas the non-SUD group had statistically significantly higher rates of discharge to inpatient rehab (26.3% vs. 8.5%, p<.001), and to skilled nursing facilities (2.3% vs. 0.2%, p<.001).

Multivariable regression analysis

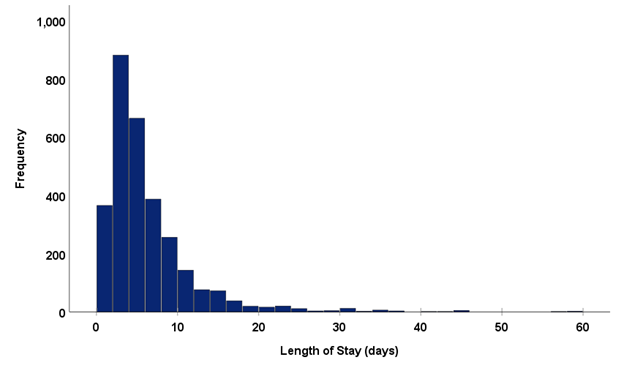

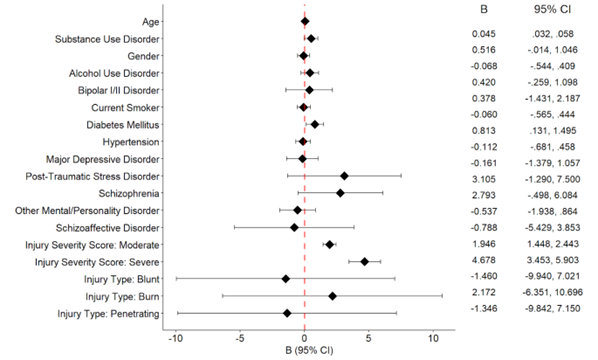

Multivariable regression analysis revealed a statistically significant positive association between age and LOS (B=0.045, p<.001). Both moderate (B=1.95, p<.001) and severe (B=4.68, p<.001) injury severity scores were statistically significantly associated with an increased LOS. Diabetes mellitus as a comorbidity was also statistically significantly associated with an increased LOS (B=0.81, p=.020). The presence of substance use disorder as a comorbidity was not statistically significant in relation to LOS, (B=0.52 (p=.056). Additionally, no statistically significant associations were found between LOS and gender, alcohol use disorder, bipolar disorder, smoking status, hypertension, major depressive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, schizophrenia, mental/personality disorders, schizoaffective disorder, or injury type. Figure 1 displays a histogram of frequency distribution of the LOS variable during the study. Figure 2 presents unstandardized regression coefficients and 95% confidence intervals from a multivariable analysis of correlates of length of stay.

|

Independent Variable |

B |

Std. Error |

Beta |

p-value |

|

Age |

.045 |

.007 |

.151 |

<.001 |

|

Substance Use Disorder |

.516 |

.270 |

.040 |

.056 |

|

Gender |

-.068 |

.243 |

-.005 |

.781 |

|

Alcohol Use Disorder |

.420 |

.346 |

.023 |

.225 |

|

Bipolar I/II Disorder |

.378 |

.922 |

.008 |

.682 |

|

Current Smoker |

-.060 |

.257 |

-.005 |

.815 |

|

Diabetes Mellitus |

.813 |

.348 |

.044 |

.020 |

|

Hypertension |

-.112 |

.291 |

-.008 |

.701 |

|

Major Depressive Disorder |

-.161 |

.621 |

-.005 |

.796 |

|

Post Traumatic Stress Disorder |

3.105 |

2.241 |

.025 |

.166 |

|

Schizophrenia |

2.793 |

1.678 |

.030 |

.096 |

|

Other Mental/Personality Disorder |

-.537 |

.715 |

-.015 |

.452 |

|

Schizoaffective Disorder |

-.788 |

2.367 |

-.006 |

.739 |

|

Injury Severity Score: Moderate |

1.946 |

.254 |

.141 |

<.001 |

|

Injury Severity Score: Severe |

4.678 |

.625 |

.135 |

<.001 |

|

Injury Type: Blunt |

-1.460 |

4.325 |

-.092 |

.736 |

|

Injury Type: Burn |

2.172 |

4.347 |

.088 |

.617 |

|

Injury Type: Penetrating |

-1.346 |

4.333 |

-.071 |

.756 |

Figure 1. Histogram showing frequency distribution of the LOS variable.

Figure 2. Forest Plot of Unstandardized Regression Coefficients and 95% Confidence Intervals from Multivariable Regression Analysis of Correlates of Length of Stay.

Note. B: Unstandardized regression coefficient; CI: Confidence Interval.

Discussion

Substance Use Disorder (SUD) is highly prevalent among trauma patients and poses major challenges to both individuals and healthcare systems globally. Among hospitalized trauma patients, the prevalence of SUD is notably high [2]. Our study provides valuable insights into the relationship between SUD and hospital length of stay (LOS) in trauma patients. Although SUD has been associated with a variety of adverse clinical outcomes, our study did not find a statistically significant relationship between SUD and LOS in trauma patients after adjusting for other covariates. Despite the lack of significance in the multivariable analysis (B=0.516, p=0.056), the results highlight a complex interaction between SUD and other factors that influence patient outcomes, underlining the importance of a multidisciplinary approach to trauma care.

A key finding was the statistically significant association between age and LOS, which suggests that older patients, regardless of SUD status, tend to have longer hospital stays. This is consistent with prior research showing that older age and frailty is associated with slower recovery and increased medical complexity following trauma [8]. Similarly, injury severity, as measured by the Injury Severity Score (ISS), or trauma related ISS (TRISS) was a significant predictor of LOS. Patients with moderate or severe injuries experienced substantially longer hospital stays, as expected, given the greater complexity and resource requirements of treating more severe injuries [9].

In multivariable regression analysis SUD was associated with half a day increase in LOS, but it did not reach statistical significance. While it was not independently associated with increased LOS, trauma patients with SUD exhibited different demographic and clinical characteristics compared to their non-SUD counterparts. SUD patients were significantly younger and more likely to be male, which underscores the distinct patient profiles typically associated with substance use and trauma [10]. SUD patients also had higher rates of alcohol use disorder, smoking, and psychiatric comorbidities such as bipolar disorder and other mental health conditions. Conditions like diabetes mellitus and hypertension were more prevalent in the non-SUD group. These findings emphasize the multifaceted nature of trauma care in SUD patients, where psychiatric and substance use comorbidities may complicate the clinical course [11–13], even if not directly prolonging hospitalization.

The SUD group had higher rates of positive toxicology screens and more frequent surgical interventions compared to the non-SUD group. This may indicate that trauma patients with SUD are more likely to present with acute intoxication or substance-related complications, requiring immediate and invasive management. However, this does not necessarily translate into longer hospital stays, potentially due to effective acute management strategies or more frequent discharges to home care, as observed in our discharge disposition analysis.

Another significant finding was the increased LOS associated with diabetes mellitus, which suggests that pre-existing metabolic conditions may delay recovery and prolong hospitalization. This is consistent with existing literature on the impact of diabetes on wound healing and recovery from trauma [14,15]. Our findings suggest that comorbid conditions like diabetes, rather than SUD, may play a greater role in determining LOS for trauma patients.

The lack of a statistically significant association between SUD and LOS in our study contrasts with some prior studies that have found longer hospital stays for patients with substance use disorders in other medical settings [8,9]. This discrepancy may reflect differences in study populations, sample size, trauma severity, or management practices. It is also possible that the multidisciplinary trauma care protocols in our Level I trauma center, which integrate mental health and addiction services, help mitigate the potential negative impact of SUD on LOS.

The findings from our study have several important implications for clinical practice. Our study highlights the importance of comprehensive trauma care. Care should address not only physical injuries but also the psychosocial and behavioral health needs of patients with SUD. While SUD itself may not independently extend LOS, the presence of targeted interventions for younger, male patients at higher risk for SUD may provide significant benefits. A multidisciplinary approach, including addiction specialists, mental health professionals, and trauma surgeons, is essential for optimizing outcomes in this vulnerable population. Our findings suggest that interventions focused on modifiable comorbidities, such as diabetes, may have a more direct impact on reducing LOS.

The retrospective nature of the analysis limits the ability to infer causality between SUD and LOS. Second, categorizing SUD based on electronic health record diagnoses may underreport the true prevalence of substance use disorders, as not all patients may have formal diagnoses documented and undocumented SUD might be misclassified in the non-SUD group. For instance, young adults may test positive for recreational drugs but deny use during history taking, which contributes to underreporting in the records. Additionally, our study focused on a single Level I trauma center, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other settings with different patient populations and management practices.

Future research should use standardized screening tools to diagnose SUD and examine factors influencing the length of stay in trauma patients with SUD. This includes exploring pain perception, pain management, psychosocial elements, 30-day mortality, hospital complications, and long-term outcomes to refine predictive models and improve patient management. Prospective studies with detailed data on substance use patterns, treatment adherence, and psychosocial factors are needed to better understand the relationship between SUD and clinical outcomes in trauma populations.

Conclusion

In our study, substance use disorder (SUD) was not an independent predictor of increased hospital length of stay for trauma patients. However, the presence of SUD complicates clinical management. A multidisciplinary approach that addresses both the physical and psychosocial needs of trauma patients with SUD is critical to optimizing outcomes. Future research should further investigate the interplay between substance use, comorbidities, and trauma care to develop better and more targeted interventions for this population.

Disclosure

The authors have no disclosures to make.

CRediT Authorship Contribution Statement

Neha Aftab: Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Revising, Project Administration, Data Curation, Validation, Supervision. Chase Smitterberg: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Antonia Vraana: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Supervision, Software, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Dia R. Halalmeh: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Supervision, Software, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Ryan J Reece: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. James A. Cranford: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. Gul R. Sachwani-Daswani: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Conceptualization.

References

2. Bråthen CC, Jørgenrud BM, Bogstrand ST, Gjerde H, Rosseland LA, Kristiansen T. Prevalence of use and impairment from drugs and alcohol among trauma patients: a national prospective observational study. Injury. 2023 Dec 1;54(12):111160.

3. DiMaggio CJ, Avraham JB, Frangos SG, Keyes K. The role of alcohol and other drugs on emergency department traumatic injury mortality in the United States. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2021 Aug 1;225:108763.

4. McGraw C, Salottolo K, Carrick M, Lieser M, Madayag R, Berg G, et al. Patterns of alcohol and drug utilization in trauma patients during the COVID-19 pandemic at six trauma centers. Injury epidemiology. 2021 Mar 22;8(1):24.

5. Hasan B, Bechenati D, Bethel HM, Cho S, Rajjoub NS, Murad ST, et al. A Systematic Review of Length of Stay Linked to Hospital-Acquired Falls, Pressure Ulcers, Central Line–Associated Bloodstream Infections, and Surgical Site Infections. Mayo Clinic Proceedings: Innovations, Quality & Outcomes. 2025 Apr 8;9(3):100607.

6. Mabry CD, Kalkwarf KJ, Betzold RD, Spencer HJ, Robertson RD, Sutherland MJ, et al. Determining the hospital trauma financial impact in a statewide trauma system. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2015 Apr 1;220(4):446–58.

7. Shymon SJ, Arthur DA, Keeling P, Rashidi S, Kwong LM, Andrawis JP. Current illicit drug use profile of orthopaedic trauma patients and its effect on hospital length of stay. Injury. 2020 Apr 1;51(4):887–91.

8. Abdelrahman H, El-Menyar A, Consunji R, Khan NA, Asim M, Mustafa F, et al. Predictors of prolonged hospitalization among geriatric trauma patients using the modified 5-Item Frailty index in a Middle Eastern trauma center: an 11-year retrospective study. European Journal of Trauma and Emergency Surgery. 2025 Dec;51(1):82.

9. Stewart N, MacConchie JG, Castillo R, Thomas PG, Cipolla J, Stawicki SP. Beyond mortality: does trauma-related injury severity score predict complications or lengths of stay using a large administrative dataset. Journal of emergencies, trauma, and shock. 2021 Jul 1;14(3):143–7.

10. Martins SS, Copersino ML, Soderstrom CA, Smith GS, Dischinger PC, McDuff DR, et al. Sociodemographic characteristics associated with substance use status in a trauma inpatient population. Journal of addictive diseases. 2007 May 24;26(2):53–62.

11. Falsgraf E, Inaba K, de Roulet A, Johnson M, Benjamin E, Lam L, et al. Outcomes after traumatic injury in patients with preexisting psychiatric illness. Journal of trauma and acute care surgery. 2017 Nov 1;83(5):882–7.

12. Parish WJ, Mark TL, Weber EM, Steinberg DG. Substance use disorders among Medicare beneficiaries: prevalence, mental and physical comorbidities, and treatment barriers. American journal of preventive medicine. 2022 Aug 1;63(2):225–32.

13. Jones CM, McCance-Katz EF. Co-occurring substance use and mental disorders among adults with opioid use disorder. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2019 Apr 1;197:78–82.

14. Regan DK, Manoli III A, Hutzler L, Konda SR, Egol KA. Impact of diabetes mellitus on surgical quality measures after ankle fracture surgery: implications for “value-based” compensation and “pay for performance”. Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma. 2015 Dec 1;29(12):e483–6.

15. Worley N, Buza J, Jalai CM, Poorman GW, Day LM, Vira S, et al. Diabetes as an independent predictor for extended length of hospital stay and increased adverse post-operative events in patients treated surgically for cervical spondylotic myelopathy. International Journal of Spine Surgery. 2017 Jan 1;11(2):10.

16. DePolo N, Bathan K, Tran Z, Peng J, Singh P, Lum SS, et al. Prospective assessment of social determinants of health and length of stay among emergency general surgery and trauma patients. The American Surgeon™. 2023 Oct;89(10):4186–90.