Abstract

Introduction: Postural and psychological dysfunction frequently coexist, especially among sedentary adults. The Lagree Method, a full-body, low-impact exercise system, may simultaneously target musculoskeletal alignment and mental health. This exploratory case series examined whether a six-week Lagree intervention could improve forward head posture (FHP), rounded shoulder posture (RSP), and psychological well-being.

Method: Eight recreationally active adults participated in a supervised six-week Lagree training protocol. Postural alignment was assessed using craniovertebral angle (CVA) and forward shoulder angle (FSA) from standardized photographs. Psychological well-being was measured using the PROMIS-29 Profile. Pre- and post-intervention scores were compared using paired t-tests or Wilcoxon signed-rank tests (α = 0.05).

Results: There was no significant change in CVA (p = 0.910); however, FSA significantly improved from 66.14° ± 8.5 to 62.70° ± 8.9 (p = 0.012). PROMIS-29 results showed significant reductions in Anxiety (p = 0.006, d = 1.36) and Fatigue (p = 0.018, r = 0.84). Pain Intensity (p = 0.059) and Depression (p = 0.068) trended toward improvement.

Conclusion: This preliminary study suggests the Lagree Method may effectively reduce RSP and enhance psychological well-being in healthy adults. While FHP did not significantly change, improvements in anxiety and fatigue highlight the potential of integrated, full-body exercise approaches for addressing both physical and mental health outcomes. Future studies with larger samples and longer duration are recommended to confirm these findings and explore clinical applicability.

Keywords

Exercise training, Forward head posture, Lagree methodology, Psychological outcomes

Introduction

Sedentary behavior is a negative lifestyle adaptation that has been associated with poor posture and psychological health. With computer and cell phone use now ubiquitous, prolonged screen time has led to postural deviations commonly referred to as “text neck” [1,2]. This condition encompasses two frequently observed maladaptations: forward head posture (FHP) and rounded shoulder posture (RSP), both of which result from musculoskeletal imbalances.

FHP is defined as an anterior translation of the head relative to the spinal column, affecting up to 67% of individuals [3] while causing increased neck pain, muscle tension, and balance deficits [4–6]. While RSP is characterized by an inward rotation of the shoulders and increased thoracic spine curvature [7], negatively impacting shoulder function and kinematics [8–10], and being correlated with increased neck and shoulder pain [11–13].

While FHP and RSP are primarily studied for their musculoskeletal consequences, growing evidence suggests these postural deviations may also influence psychological well-being. This idea is supported by the theory of embodied cognition which points to the notion that the body is a physical representation of an individual’s psychological state [14–16]. Previous research has linked these postures to characteristics such as sadness [17], submissiveness [18,19], and lowered self-esteem [20]. Consequently, given the success seen in tailored exercise prescription for addressing the physical presentation of FHP and RSP [21–23], further research is warranted to determine whether these physical improvements correspond with changes in psychological state.

While research supports the efficacy of exercise in treating FHP and RSP, these conditions are often addressed in isolation [24], with interventions often overlooking the links between postural dysfunction and psychological health. Integrated rehabilitation, which is a standard approach for complex lower extremity dysfunction, has been underutilized when treating negative upper body postural presentations [25]. A holistic, full-body exercise modality that can simultaneously address both postural alignment and its associated neuromuscular deficits is therefore needed.

The Lagree Method is a multimodal exercise modality that aligns with the principles of integrated rehabilitation. Its emphasis on slow, controlled, full-body movements using progressive resistance promotes the neuromuscular re-education through integration of whole-body motor control [26]. By integrating core stability, strength, and proprioceptive training, Lagree offers a promising method for simultaneously addressing the dual postural faults of FHP and RSP. However, no studies have investigated its feasibility or effectiveness for this application.

Therefore, the purpose of this exploratory case series is to evaluate the impact of a 6-week Lagree Method program on posture and psychological health. We will measure postural changes using the craniovertebral angle (CVA) and forward shoulder angle (FSA), and assess physical, mental, and social health outcomes using the PROMIS-29 questionnaire. We hypothesize that the Lagree intervention will improve postural alignment and psychological outcomes, demonstrating its efficacy as an integrated approach for addressing both physical and psychological dysfunction in recreationally active populations.

Methods

Participants

The current study was an exploratory case series employing a novel 6-week exercise intervention with measurements taken at pre- and post-intervention. Eleven adults were recruited from a Texas-based university campus from January to May 2024. The pre- and post-intervention assessments, which included the completion of all paper-based questionnaires and the collection of physical measurements, as well as the exercise intervention took place in a research laboratory at university facilities to ensure consistency and control.

Inclusion criteria required participants to be between 18 and 65 years old, free from acute injuries or surgeries within the past six months, without known balance or equilibrium deficits, and participating in ≥150 min/week of moderate activity per week. Participant attrition reduced the sample size to eight individuals who completed both pre- and post-intervention assessments. Reasons for attrition included injury, illness, or personal scheduling conflicts unrelated to the study. The demographic characteristics of the participants who completed the study are summarized in Table 1. The study was approved by the Sam Houston State University Institutional Review Board (IRB-2024-35), and all participants provided written informed consent prior to data collection.

|

|

Mean ± SD |

Range |

|

N (sex) |

7(F), 1(M) |

|

|

Age (years) |

26.13 ± 9.9 |

19–48 |

|

Height (cm) |

162.89 ± 12.4 |

149.86–188.0 |

|

Mass (kg) |

71.63 ± 22.1 |

44.00–100.0 |

|

Sedentary Time (mins/day) |

426.23 ± 175.3 |

171–780 |

|

Descriptive statistics of participant demographics, including sex, age, height, mass, and sedentary time. Sedentary time was assessed using Q26 and Q27 of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ). Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables. |

||

Study design and data collection

Pre- and post-testing protocols: Psychological measures were assessed by the various domains of the Patient Reported Outcome Measurement Information System-29 (PROMIS-29).

The PROMIS-29 is a widely used tool for assessing physical, mental, and social health outcomes, particularly in studies of physical activity interventions [27–30]. With a high degree of validity and reliability [31,32], the standardized T-score measure allows for meaningful comparisons across populations, conditions, and treatments, enabling an integrated approach for evaluating pain, function, and quality of life [32]. Domains included Physical Function, Anxiety, Depression, Fatigue, Sleep Disturbance, Ability to Participate in Social Roles and Activities, and Pain Interference. A minimal clinically important difference (MCID) of 5.0 points has been proposed as a reasonable estimate for PROMIS-29 scales, a value supported by a synthesis of existing findings [33]. Additionally, a standalone PROMIS-29 Pain Intensity rating scores pain on a numeric scale from 0-10. Participants completed the surveys at two time points: a baseline pre-test and a post-test. The average time between these visits was 6 weeks, consistent with the duration of the exercise intervention. While the 6-week intervention period was standardized, the scheduling of individual sessions was flexible to accommodate each participant's availability. The surveys took approximately 10 minutes to complete at each time point.

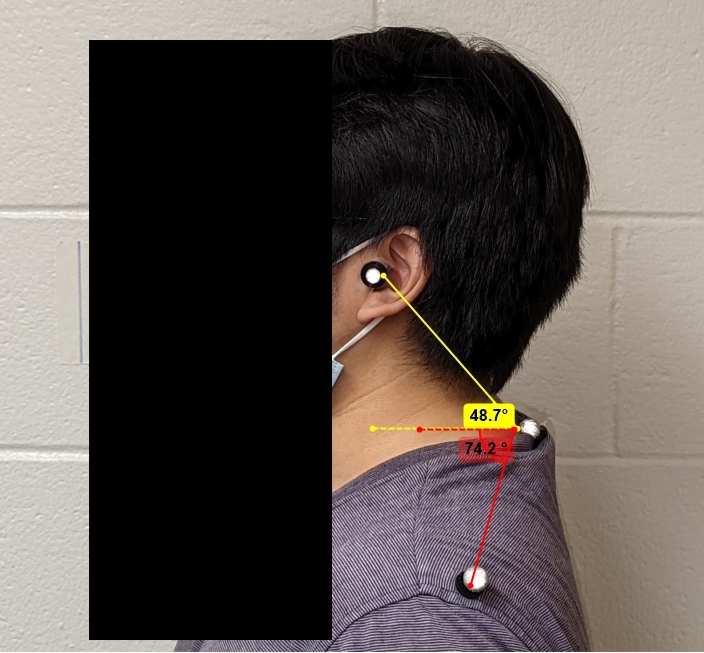

Postural analysis: Forward Shoulder Angle (FSA) and Craniovertebral Angle (CVA) were employed to assess RSP and FHP, respectively, as both have been validated as reliable and accurate measurement techniques [34–37]. To ensure consistency during analysis, reflective markers were placed on key anatomical landmarks: the seventh cervical vertebra (C7), the tragus of the right ear, and the posterolateral aspect of the right acromion (PLA). These markers were used as visual indicators for static images, and camera flash ensured visibility for analysis. Participants were first instructed to adopt a neutral posture by standing in a relaxed manner with their feet shoulder-width apart and arms at their sides. To prevent a startle reflex from the flash, participants were asked to look forward and briefly close their eyes for approximately one second. This specific duration was chosen to be long enough to avoid the flash, yet short enough to minimize any potential balance compensation.

FSA was defined as the absolute angle formed between the C7 and the PLA, relative to the horizontal plane (Figure 1). While CVA, was defined as the absolute angle between the C7 and the tragus of the ear, relative to the horizontal plane. Photographs were captured from the participant's right side in the sagittal plane. To ensure a standardized procedure, an iPhone 13 Pro (Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA, USA) was mounted on a tripod and oriented horizontally (landscape mode). The main camera lens was positioned at the participant's shoulder height and placed approximately 1 meter away to ensure the relevant landmarks were framed within the shot (Figure 1). The phone's main 12 MP wide-angle camera was used with its default settings, which features a 26 mm equivalent focal length and an ƒ/1.5 aperture. Images were captured at the camera's standard high resolution. Images were analyzed, and angular measurements were extracted using Kinovea software (Version 0.9.5), which has been shown to be validated tool for accurate kinematic analysis [38–40]. A single, experienced researcher performed all analyses to ensure high intra-rater reliability. For angular measurements, the reference point was consistently identified as the base of the reflective marker at the skin's surface, not its geometric center. This protocol was used to designate the true anatomical landmark and avoid measurement error from the marker's physical depth.

Figure 1. Postural measurement. Reflective motion capture markers are placed on the C7 vertebrae, tragus of the ear, and the posterior-lateral acromion. Craniovertebral Angle (yellow) and Forward Shoulder Angle (red) are depicted. C7: Seventh Cervical Vertebrae.

Lagree intervention: Participants engaged in a 6-week Lagree Method intervention, with sessions conducted two times per week, utilizing a Lagree Mini Pro (Lagree Fitness, Los Angeles, CA, USA) under the guidance of trained researchers. Depending on scheduling availability, participants completed the sessions either individually or in pairs. The program, designed by an external, expert Lagree instructor, followed a strict order of exercises as dictated by an instructional video to ensure a uniform stimulus. The intervention involved progressive resistance training incorporating a controlled tempo to enhance strength, balance, and endurance, with intensity and duration systematically increasing over the intervention period. It is important to note that the Lagree protocol implemented in this study was a general fitness regimen and was not specifically designed with consideration of the postural or psychological outcome measures evaluated.

Exercise progressions began with foundational stability movements like planks and lunges, before progressing to more complex, multi-planar exercises that challenged dynamic control. The final phase integrated advanced techniques, such as pulsing movements and integrated core exercises, to maximize muscular endurance and motor control. To ensure consistency, safety, and adherence to the instructional video, an in-person certified Level 1 Lagree instructor supervised all sessions, ensuring participant safety and adherence to protocol.

Statistical analysis

The intervention's effects on the postural and psychological outcomes were analyzed by comparing pre- and post-test data for posture and PROMIS-29 measures. Normality of the data was assessed using Shapiro-Wilk Test. Paired t-tests were used for normally distributed variables, and the Wilcoxon signed-ranks test was employed for non-normally distributed variables. Changes in each variable were reported as mean ± SD, and test statistics (t or Z) and corresponding p-values were included. Alpha level was set a priori to 0.05. Effect sizes were reported for each domain, using Cohen’s d for paired t-tests and r for Wilcoxon tests, to provide a measure of meaningfulness, practical significance and compliment statistical significance results.

Results

Posture

Craniovertebral angle (CVA) and forward shoulder angle (FSA) were assessed pre- and post-intervention to evaluate changes in postural alignment (Table 2). No significant difference was observed in CVA scores between pre- (51.45 ± 5.1°) and post-intervention (51.33 ± 4.9°), t(7) = -0.447, p = 0.910. In contrast, FSA scores demonstrated a significant reduction from pre- (66.14 ± 8.5°) to post-intervention (62.70 ± 8.9°), t(7) = 3.36, p = 0.012, indicating an improvement in shoulder alignment.

|

Measure |

Pre-Intervention (Mean ± SD) |

Post-Intervention (Mean ± SD) |

t |

p-value |

Effect Size (95% CI) |

|

CVA (°) |

51.45 ± 5.1 |

51.33 ± 4.9 |

t(7) = -0.447 |

0.910 |

d = 0.41 |

|

FSA (°) |

66.14 ± 8.5 |

62.70 ± 8.9 |

t(7) = 3.36 |

0.012* |

d = 1.19 |

|

CVA: Craniovertebral Angle; FSA: Forward Shoulder Angle. *Significant at p<0.05. Effect sizes are reported using Cohen's d. |

|||||

PROMIS-29

Table 3 presents the comparison of pre- and post-intervention scores across PROMIS-29 domains. Significant improvements were observed in Anxiety (t(7) = 3.849, p = 0.006, d = 1.36) and Fatigue (Z = -2.366, p = 0.018, r = 0.84), reflecting reduced levels in both domains following the intervention.

Other domains, including Pain Intensity (p = 0.059), Depression (p = 0.068), Physical Function (p = 0.655), Sleep Disturbance (p = 0.551), Social Roles (p = 0.069), and Pain Interference (p = 1.000), demonstrated no significant differences between pre- and post-intervention scores.

|

Domain |

Pre-Intervention (Mean ± SD) |

Post-Intervention (Mean ± SD) |

Statistical Test |

p-value |

Effect Size (95% CI) |

|

Physical Function |

54.34 ± 4.8 |

54.34 ± 5.1 |

Wilcoxon, |

0.655 |

r = 0.16 |

|

Anxiety |

58.50 ± 9.9 |

51.79 ± 9.1 |

t(7) = 3.849 |

0.006* |

d = 1.36 |

|

Depression |

51.93 ± 10.0 |

46.87 ± 8.5 |

Wilcoxon, |

0.068 |

r = 0.65 |

|

Fatigue |

52.19 ± 5.1 |

45.40 ± 6.7 |

Wilcoxon, |

0.018* |

r = 0.84 |

|

Sleep Disturbance |

48.70 ± 9.0 |

46.83 ± 8.8 |

Wilcoxon, |

0.551 |

d = 0.22 |

|

Social Roles |

54.22 ± 6.9 |

58.29 ± 6.7 |

t(7) = -2.149 |

0.069 |

d = -0.76 |

|

Pain Interference |

46.85 ± 7.2 |

46.65 ± 5.7 |

Wilcoxon, |

1.000 |

r = 0.00 |

|

Pain Intensity |

1.38 ± 1.4 |

0.75 ± 0.9 |

Wilcoxon, |

0.059 |

r = 0.67 |

|

Comparison of pre- and post-intervention scores across PROMIS-29 domains. Paired t-tests were used for normally distributed data; Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were used for non-parametric comparisons. "Ability to Participate in Social Roles and Activities" has been shortened to "Social Roles" for brevity. Significant p-values (p<0.05) are marked with an asterisk (*), and effect sizes are reported using Cohen's d for t-tests and r for Wilcoxon tests. |

|||||

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the effects of the Lagree Method on neck and shoulder posture measures and psychological outcomes. The 6-week Lagree Method intervention demonstrated significant improvements in RSP, Anxiety, and Fatigue. These preliminary findings suggest that the Lagree Method may be a promising intervention for addressing both postural alignment and psychological health, warranting further investigation in a larger, controlled trial. Despite no significant changes observed in CVA, or other PROMIS-29 domains, trends for improvement were seen for Pain Intensity and Depression.

A key finding of this study was the significant improvement in both Anxiety and Fatigue, which supports the theoretical framework of embodied cognition that highlights the notion that posture and psychological state are bidirectionally linked. Our results align with this framework, suggesting that an intervention capable of improving postural alignment (RSP in this case) can also produce psychological benefits. This is consistent with findings from other mind-body research demonstrating the link between RSP and negative psychological outcomes [19,20,41–44].

This positive psychological effect is further supported by the positive trends observed in other PROMIS domains. While this study did not find statistically significant changes in Pain Intensity, Depression, and Ability to Participate in Social Roles, the p-values for these outcomes (p = 0.059 to 0.069) were noteworthy. Given the study's limited statistical power, the lack of significance may be a result of a Type II error rather than the absence of a true effect, suggesting that meaningful benefits may be detectable in a larger, more adequately powered trial.

In contrast to the RSP improvements, the intervention did not significantly change CVA. This finding is likely explained by the participants' baseline characteristics, as their CVA measurements already exceeded the clinical threshold for FHP (>50°) [45]. With a healthy postural baseline in this specific metric, there was limited potential for improvement. While the Lagree Method is a holistic, whole-body approach, future research might explore if adding exercises that specifically target the deep cervical flexors [46,47] could yield additional psychological benefits, given the established link between FHP and psychological state [17,41,47].

Alkan et al. [48] reported the minimal detectable changes (MDC) for various domains of the PROMIS-29, providing estimates for both 90% (MDC90) and 95% (MDC95) certainty levels. Comparing their data with our findings for Anxiety and Fatigue, the mean changes of 6.79 and 6.71, respectively, exceed the MDC90 thresholds reported by Alkan et al. [48] (6.67 for Anxiety and 5.13 for Fatigue). However, when considering the more stringent MDC95 thresholds (7.95 for Anxiety and 6.12 for Fatigue), only the mean change in Fatigue surpasses this level. This indicates that improvements in Fatigue are not only statistically significant (p = 0.018, r = 0.84) but also likely to represent a meaningful change perceptible to participants in daily life. In contrast, the observed Anxiety improvement, while statistically significant (p = 0.006, d = 1.36), approaches but does not fully exceed the 95% confidence threshold, suggesting a smaller, potentially borderline perceptible benefit. Additionally, as this study was conducted on a college campus, academic stressors such as examinations may have influenced psychological outcomes, as suggested by previous research [49–51]. Despite these considerations, our findings in a healthy population with no prior mental or physical diagnoses suggest that the Lagree Method may serve as a promising tool for enhancing psychological well-being, even in non-clinical populations.

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, the sample size was relatively small, which limits the generalizability of the results. Furthermore, the study's design as an exploratory case series did not include a control group. Consequently, it is not possible to definitively attribute the observed changes solely to the intervention without having a comparison group to establish causal inferences. The study's statistical power was further limited by participant attrition, reducing the final sample from 11 to 8. The dropouts were unrelated to the intervention and were attributed to external factors, including personal injury, illness, and scheduling conflicts common in a university setting. This underscores the importance of developing improved participant retention strategies for future research. Despite these limitations, the promising preliminary findings justify a more rigorous, controlled trial to confirm these results and establish causality.

Second, the intervention duration of 6 weeks may not have been sufficient to detect significant changes in all outcome measures, particularly in PROMIS-29 domains such as Pain Intensity and Depression, which showed trends for improvement. The absence of statistical significance in these areas should be interpreted with caution, as it may represent a Type II error (a false negative) resulting from an insufficient intervention period rather than a true lack of a therapeutic effect. Therefore, future research would benefit from incorporating a longer intervention period and a follow-up assessment to determine if the observed benefits are sustained over time.

Third, the lack of a universally accepted gold standard for measuring RSP complicates the interpretation of results. Although FSA served as a proxy for RSP, the absence of clinical gold standard for its assessment introduces potential variability. Similarly, the participants’ baseline CVA values exceeded the clinical threshold for FHP (<50°), which may have limited the potential for significant improvement in FHP within this healthy population. Future studies should consider recruiting participants with more pronounced postural dysfunction to explore the intervention’s efficacy in a broader range of populations.

Finally, while this study's findings suggest potential benefits, it is important to consider the intervention itself. The Lagree Method is a commercial fitness program that, while enhancing the study's real-world applicability, relies on proprietary equipment and specialized instructor training. This may limit the ability of other researchers to replicate the protocol and could affect the generalizability of these findings.

Despite these limitations, this study provides preliminary evidence supporting the Lagree Method’s potential to enhance psychological and physical health. Future research with larger, more diverse samples, extended intervention durations, and inclusion of a control group will be essential to validate and expand upon these findings.

Conclusion

This study explores the effects of the Lagree Method on posture and psychological outcomes. Significant improvements in RSP, and PROMIS-29 domains of Anxiety and Fatigue suggest its potential efficacy for enhancing both physical and mental health. While no significant changes were found in forward head posture or other PROMIS-29 domains, trends toward improvement in pain intensity and depression highlight the need for further research with larger samples and longer interventions. These findings support the Lagree Method as a promising holistic exercise modality for addressing poor posture, and psychological distress. Future studies should further explore its long-term benefits, particularly with a larger, controlled trial.

Clinical Relevance

- The Lagree Method may be an effective intervention for improving rounded shoulder posture in recreationally active adults.

- Psychological improvements, particularly in anxiety and fatigue, suggest Lagree’s potential utility in mental health support through movement.

- The integrated, full-body nature of Lagree offers a practical approach for addressing postural and psychological concerns simultaneously.

Declarations of Interest

None.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Sebastien Lagree for his donation of Lagree Fitness equipment and for providing the foundational design of the exercise protocol used in this study. The protocol was a general fitness regimen and was not specifically designed to target or correct posture. Sebastien was not involved in the execution, data collection, analysis, or interpretation of the study, and his contributions did not influence the reporting of results.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest related to this contribution.

References

2. Neupane S, Ali U, Mathew A. Text neck syndrome-systematic review. Imperial Journal of Interdisciplinary Research. 2017;3(7):141–8.

3. Ramalingam V, Subramaniam A. Prevalence and associated risk factors of forward head posture among university students. Indian J. Public Health Res. Dev. 2019 Jul;10:775.

4. Lin G, Zhao X, Wang W, Wilkinson T. The relationship between forward head posture, postural control and gait: A systematic review. Gait & posture. 2022 Oct 1;98:316–29.

5. Pratama DA, Sulistiyono RD, Rachman RA, Prayudho S. Causes, effects and treatment of forward head posture. Systematic literatur review. Fizjoterapia Polska. 2024 Jun 1(3).

6. Szczygieł E, Fudacz N, Golec J, Golec E. The impact of the position of the head on the functioning of the human body: A systematic review. International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health. 2020 Jul 23;33(5):559–68.

7. Kim EK, Kim JS. Correlation between rounded shoulder posture, neck disability indices, and degree of forward head posture. Journal of Physical Therapy Science. 2016;28(10):2929–32.

8. Lee JH, Cynn HS, Yoon TL, Ko CH, Choi WJ, Choi SA, et al. The effect of scapular posterior tilt exercise, pectoralis minor stretching, and shoulder brace on scapular alignment and muscles activity in subjects with round-shoulder posture. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology. 2015 Feb 1;25(1):107–14.

9. Ludewig PM, Cook TM. Alterations in shoulder kinematics and associated muscle activity in people with symptoms of shoulder impingement. Physical Therapy. 2000 Mar 1;80(3):276–91.

10. Ludewig PM, Reynolds JF. The association of scapular kinematics and glenohumeral joint pathologies. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2009 Feb;39(2):90–104.

11. Azevedo DC, de Lima Pires T, de Souza Andrade F, McDonnell MK. Influence of scapular position on the pressure pain threshold of the upper trapezius muscle region. European Journal of Pain. 2008 Feb 1;12(2):226–32.

12. Battecha KH, Alayat MS, Mousa GS, HM M, Thabet AA, Ebid AA, et al. Correlation of head and shoulder posture with non-specific neck pain: A cross-sectional study. SPORT TK-Revista EuroAmericana de Ciencias del Deporte. 2024 Nov 22;13:59.

13. Hwang UJ, Kwon OY, Yi CH, Jeon HS, Weon JH, Ha SM. Predictors of upper trapezius pain with myofascial trigger points in food service workers: The STROBE study. Medicine. 2017 Jun 1;96(26):e7252.

14. Anderson ML. Embodied cognition: A field guide. Artificial intelligence. 2003 Sep 1;149(1):91–130.

15. Leitan N, Chaffey L. Embodied cognition and its applications: A brief review. Sensoria: A Journal of Mind, Brain & Culture. 2014;10:3–10.

16. Shapiro L. Embodied Cognition. Routledge; 2010.

17. Coulson M. Attributing emotion to static body postures: Recognition accuracy, confusions, and viewpoint dependence. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior. 2004 Jun;28(2):117–39.

18. Manusov V, Patterson ML, Burgoon JK, Dunbar NE. Nonverbal expressions of dominance and power in human relationships. In: Patterson ML, Manusov V, Editors. The Sage handbook of nonverbal communication.. SAGE Publications, Inc; 2006. pp. 279–98.

19. Mehrabian A. Nonverbal communication. Routledge; 2017.

20. Ramezanzade H, Arabnarmi B. Relationship of self esteem with forward head posture and round shoulder. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2011 Jan 1;15:3698–702.

21. Sepehri S, Sheikhhoseini R, Piri H, Sayyadi P. The effect of various therapeutic exercises on forward head posture, rounded shoulder, and hyperkyphosis among people with upper crossed syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2024 Feb 1;25(1):105.

22. Sheikhhoseini R, Shahrbanian S, Sayyadi P, O’Sullivan K. Effectiveness of therapeutic exercise on forward head posture: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics. 2018 Jul 1;41(6):530–9.

23. Yang S, Boudier-Revéret M, Yi YG, Hong KY, Chang MC. Treatment of chronic neck pain in patients with forward head posture: a systematic narrative review. Healthcare. 2023 Sep 22;11(19):2604.

24. Page P, Frank C, Lardner R. Assessment and treatment of muscle imbalance: The Janda approach. Journal of Orthopedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2011;41:799–800.

25. Lauman ST, Anderson DI. A neuromuscular integration approach to the rehabilitation of forward head and rounded shoulder posture: Systematic review of literature. Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2021 Oct 25;3(2):61–72.

26. Greenberg M, Brzenski A. Using the Lagree Megaformer TM for Rehabilitation in Patient with Severe Neuromuscular Dysfunction and Deconditioning: A Case Report. The Internet Journal of Neurology. 2016;19(1).

27. Ahmad E, Joubert P, Oppenheim G, Bindler R, Zimmerman D, Lyle-Edrosolo G, et al. Resistance training:(Re) thinking workplace health promotion: a pilot study. Nurse Leader. 2024 Aug 1;22(4):399–407.

28. Arrant KR, Stewart MW. The effects of a yoga intervention. Journal of Interprofessional Practice and Collaboration. 2020;2(2):7.

29. Callahan LF, Cleveland RJ, Altpeter M, Hackney B. Evaluation of tai chi program effectiveness for people with arthritis in the community: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity. 2016 Jan 1;24(1):101–10.

30. Norton EL, Wu KH, Rubenfire M, Fink S, Sitzmann J, Hobbs RD, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness after open repair for acute type A aortic dissection–a prospective study. Seminars in Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2022 Sep 1;34(3):827–39.

31. Hays RD, Spritzer KL, Schalet BD, Cella D. PROMIS®-29 v2. 0 profile physical and mental health summary scores. Quality of life Research. 2018 Jul;27(7):1885–91.

32. Houwen T, de Munter L, Lansink KW, de Jongh MA. There are more things in physical function and pain: a systematic review on physical, mental and social health within the orthopedic fracture population using PROMIS. Journal of Patient-Reported Outcomes. 2022 Apr 6;6(1):34.

33. Khutok K, Janwantanakul P, Jensen MP, Kanlayanaphotporn R. Responsiveness of the PROMIS-29 scales in individuals with chronic low back pain. Spine. 2021 Jan 15;46(2):107–13.

34. Brunton JBE, Ni Mhuiri A. Reliability of measuring natural head posture using the craniovertebral angle. Irish Ergonomics Review. 2003;37–41.

35. Dimitriadis Z, Podogyros G, Polyviou D, Tasopoulos I, Passa K. The reliability of lateral photography for the assessment of the forward head posture through four different angle‐based analysis methods in healthy individuals. Musculoskeletal Care. 2015 Sep;13(3):179–86.

36. Mostafaee N, HasanNia F, Negahban H, Pirayeh N. Evaluating differences between participants with various forward head posture with and without postural neck pain using craniovertebral angle and forward shoulder angle. Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics. 2022 Mar 1;45(3):179–87.

37. Singla D, Veqar Z, Hussain ME. Photogrammetric assessment of upper body posture using postural angles: a literature review. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine. 2017 Jun 1;16(2):131–8.

38. Elrahim RM, Embaby EA, Ali MF, Kamel RM. Inter-rater and intra-rater reliability of Kinovea software for measurement of shoulder range of motion. Bulletin of Faculty of Physical Therapy. 2016 Dec;21(2):80–7.

39. Puig-Diví A, Escalona-Marfil C, Padullés-Riu JM, Busquets A, Padullés-Chando X, Marcos-Ruiz D. Validity and reliability of the Kinovea program in obtaining angles and distances using coordinates in 4 perspectives. PloS one. 2019 Jun 5;14(6):e0216448.

40. Sharifnezhad A, Raissi GR, Forogh B, Soleymanzadeh H, Mohammadpour S, Daliran M, et al. The Validity and Reliability of Kinovea Software in Measuring Thoracic Kyphosis and Lumbar Lordosis. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal. 2021 Jun 10;19(2):129–36.

41. Dehcheshmeh TF, Majelan AS, Maleki B. Correlation between depression and posture (A systematic review). Current Psychology. 2024 Sep;43(33):27251–61.

42. Rosario JL, Diógenes MS, Mattei R, Leite JR. Differences and similarities in postural alterations caused by sadness and depression. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies. 2014 Oct 1;18(4):540–4.

43. Do Rosário JL, Diógenes MS, Mattei R, Leite JR. Can sadness alter posture?. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies. 2013 Jul 1;17(3):328–31.

44. Wilkes C, Kydd R, Sagar M, Broadbent E. Upright posture improves affect and fatigue in people with depressive symptoms. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2017 Mar 1;54:143–9.

45. Ruivo RM, Carita AI, Pezarat-Correia P. The effects of training and detraining after an 8 month resistance and stretching training program on forward head and protracted shoulder postures in adolescents: Randomised controlled study. Manual therapy. 2016 Feb 1;21:76–82.

46. Hussein HY, Fayez ES, El Fiki AA, Elzanaty MY, El Fakharany MS. Effect of deep neck flexor strengthening on forward head posture: A systemic review and meta-analyses. Ann Clin Anal Med. 2021 Jan 1;12:114–9.

47. Popli S, Yogeshwar D, Kumar R, Singh J, Verma S, Lamba VK 2024 Correlation of Forward Head Posture with Perceived Stress and its Impact on Activity of Daily Living Among Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study. J Adv Sport Phys Edu 7, 206–12.

48. Alkan A, Carrier ME, Henry RS, Kwakkenbos L, Bartlett SJ, Gietzen A, et al. Minimal Detectable Changes of the Health Assessment Questionnaire–Disability Index, Patient‐Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System‐29 Profile Version 2.0 Domains, and Patient Health Questionnaire‐8 in People With Systemic Sclerosis: A Scleroderma Patient‐Centered Intervention Network Cohort Cross‐Sectional Study. Arthritis Care & Research. 2024 Nov;76(11):1549–57.

49. Fejes I, Ábrahám G, Legrady P. The effect of an exam period as a stress situation on baroreflex sensitivity among healthy university students. Blood Pressure. 2020 May 3;29(3):175–81.

50. Folkman S, Lazarus RS. If it changes it must be a process: study of emotion and coping during three stages of a college examination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1985 Jan;48(1):150.

51. Stojanovic G, Vasiljevic-Blagojevic M, Stankovic B, Terzic N, Terzic-Markovic D, Stojanovic D. Test anxiety in pre-exam period and success of nursing students. Experimental and Applied Biomedical Research (EABR). 2018;19:167–74.