Abstract

Background: People living with HIV (PLWH) are more likely to experience chronic pain, trauma, and analgesic use than their HIV-negative counterparts. This complex chronic pain profile can have subsequent physical, mental, and psychological sequela. Despite this, a tool to rapidly screen at risk patients and refer to specialized care has not been established. The purpose of this scoping review is to identify current screening tools for chronic pain, trauma, and opioid use to guide design of our comprehensive HOPE (HIV, Opioids and Pain Experience) screening tool.

Methods: A systematic search was conducted using a combination of controlled vocabulary and natural language keywords across four electronic databases to identify relevant peer-reviewed studies. Data extraction from eligible studies was then performed to summarize and organize findings according to the topic of the outcome measurement tool.

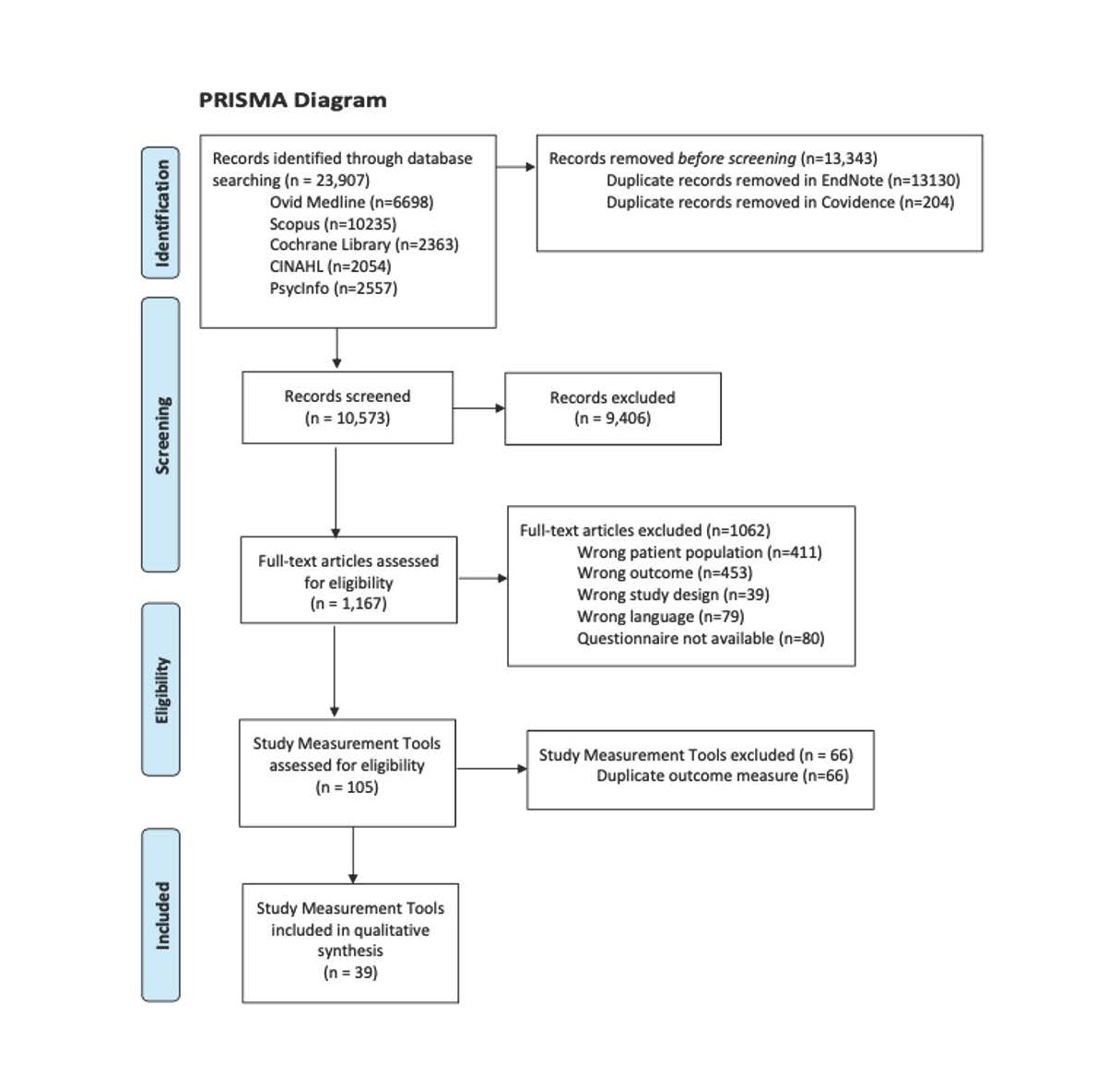

Results: A total of 10,573 abstracts were identified, 1,167 full-text articles reviewed, and 39 included for final data extraction. Among these articles, 31 screeners were identified for pain assessment, 8 for detecting opioid misuse, and 7 for trauma evaluation.

Discussion and conclusions: This study revealed tools for screening of chronic pain, trauma and opioid use described in the literature that can be used in the creation of an innovative screening tool for all the above in an HIV clinical context. All extracted tools demonstrated good validity and reliability, indicating their potential for inclusion in the development of a multidimensional screener for complex chronic pain among PLWH.

Keywords

Chronic Pain, HIV, Trauma

Introduction

Of the over 1 million adults and adolescents living with HIV in the United States, up to 85% are estimated to live with chronic pain: nearly eight times the rate of their HIV-negative peers [1,2]. Chronic pain is one of the most frequently reported symptoms in PLWH, and can have a drastic impact on HIV care retention, adherence to treatment, and patient quality of life, ultimately affecting daily functioning, overall physical and mental health, and social and family relationships [1,3,4]. Even in the presence of HIV virologic control, pain can become chronic and persistent if underlying complexities associated with substance use, trauma, and/or mental health issues are also not identified and addressed. As a result, strategies to rapidly identify and refer to specialized care for PLWH who are at high risk for developing complex chronic pain as identified by Pullen and Nuñez [5] are essential to patient wellness.

Analgesic management in PLWH can be highly complex due to a high prevalence of mood disorders, substance abuse histories, hyperalgesia and polypharmacy in this population [6,7]. Persons living with HIV, particularly those with a history of trauma and/or substance use, may be at a higher risk for potential drug-drug interactions (pDDIs) between over-the-counter and prescription analgesics and ART [8]. In addition, despite -- or perhaps because of -- the proliferation of local, state, and national efforts to curtail opioid use disorder in the last decade [9]. PLWH are more likely than members of the general population to be prescribed opioids and to be given higher doses of opioids, putting them at increased risk for opioid use disorder [10].

Several studies have shown that PLWH with opioid use disorders tend to be less adherent to antiretroviral therapy than PLWH who do not use opioids, putting them at risk for virologic activation and ART resistance [11]. Furthermore, studies have found that self-reported levels of opioid usage remain the same in PLWH who have completed a course of chronic pain focused physical therapy, even when they report decreased pain and decreased usage of non-opioid analgesics (e.g., non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen, and neuropathic pain medications) [5,9]. This highlights the importance of early detection of pain to avoid opioid initiation and misuse. Therefore, innovative HIV care delivery models that screens for pain and opioid use prior to a patient’s initial HIV clinical encounter can have a potential for positive downstream effects including reductions in opioid initiation, increases in retention in care, and maintenance of viral suppression.

It is also important to note that chronic complex pain in PLWH can also be affected by exposure to traumatic events. Trauma is defined by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) as “an event experienced by an individual physically or emotional harmful and/or life-threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on an individual's functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being” [12]. It is estimated that 51-81% of all adults in high-income countries, such as the US, have experienced a minimum of one traumatic event. Of these, a significant number report, experiencing multiple traumatic events throughout their lifetime [13]. There is an even higher prevalence of trauma among PLWH: one study estimates that 68% - 98% of women, 68% - 77% of men, and 93% of transgender people with HIV within the United States have experienced some sort of trauma, with 30% of all HIV infected individuals experiencing physical and/or sexual abuse before the age of 13 [13]. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among PLWH is as high as 74% compared to only 8% among the general US population [14].PLWH who have experienced trauma are more likely to experience a higher incidence of pain, more pain conditions, and increased severity of pain in comparison to their HIV-negative counterparts: up to 50% of PLWH with chronic pain report having PTSD in comparison to only 6-12% of their HIV negative counterparts [14,15]. While this likely has a multifaceted etiology, these discordant rates may be at least partially attributed to lower thresholds for physiologic pain found in people with both chronic pain and trauma exposure [16].

The extent to which validated screening and assessment tools have been used to better direct and coordinate care of PLWH with complex chronic pain (CCP) is unknown. The purpose of this scoping review is to identify and summarize existing validated measurement tools currently used to screen for and assess chronic pain, trauma, and analgesic use in adults over 18 years of age. A scoping review is an appropriate synthesis strategy for this research, as an approach to identify and describe existing validated assessment and screening tools used by a range of primary and interdisciplinary healthcare settings [17]. Data from this scoping review will be used to identify and synthesize items/questions that assess and screen for biopsychosocial factors of chronic pain, trauma, and analgesic use, which will further inform the development of a multidimensional screening tool for CCP among PLHIV.

Methods

Eligibility criteria

This review aimed to find and assess all validation studies of tools that measure and screen chronic pain, trauma, and analgesic use in adults. Studies included were those of current validated tools; studies that include validation of initial measurement tools and adaptations of tools for other populations; and studies that include psychometric measurement data of measurement tools. Excluded reports include tools that are proposed but not validated; studies reporting outcome measurement changes following intervention or assessment but that do not contribute to the validation of the outcome measure; studies involving diagnostic criteria; validation of existing tools to languages other than Spanish or English; studies on pain sequelae to surgical interventions, oncological interventions, acute physical trauma, and central diagnoses of central post stroke pain, spinal cord injury, traumatic brain injury, Parkinson's disease, or multiple sclerosis. Studies published in a language other than English or Spanish were excluded, as well as studies of measurement tools involving the use of artificial intelligence. The eligibility criteria are also represented in Table 1.

|

Eligibility criteria |

||

|

PCC Question |

Inclusion Criteria |

Exclusion Criteria |

|

Population |

Adults of and higher than the age of 18 |

Pediatric patients under the age of 18 |

|

Intervention/Exposure |

Current validated measurement tools used by interdisciplinary healthcare providers to assess and screen chronic pain, trauma, and analgesic use. |

Tools not validated (proposed only)

|

|

Studies that include validation of measurement tool, initial and adapted for other populations not in exclusion criteria. |

Studies reporting outcome measurement changes following intervention or assessment but do not contribute to validation of outcome measure. |

|

|

Studies that include psychometric measurement data of measurement tool. |

Studies involving diagnostic criteria contributing to definitions for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. |

|

|

Validation of existing tools to other language other than Spanish or English. |

||

|

Studies on pain sequelae to the following: surgical interventions oncological interventions acute physical trauma central diagnoses: Central post stroke (CVA) pain, Spinal Cord Injury, Traumatic Brain Injury, Parkinson’s disease, or Multiple Sclerosis. |

||

|

Outcome |

List of items/questions on the tool, or link/method to access items |

Survey unavailable (e.g. cost to obtain survey, original survey written in language other than Spanish or English) -Outcome measurement does directly involve single topic or any combination of chronic pain, behavioral health/trauma, and analgesic use |

|

Objective measurement tool used in combination with data from larger inventory that does not meet inclusion criteria. |

||

|

Others |

|

Surgery Artificial intelligence |

|

Languages |

Spanish & English |

|

Literature search

A systematic search was developed by a health sciences librarian (ER) using a combination of controlled vocabulary and natural language keywords. The search strategy encompassed the concepts of the measurement of chronic pain, psychological trauma, and analgesic use and misuse. Additional keywords to identify validation studies, as well as the "Validation Studies" study type (in applicable databases) were used. The search strategy was developed in Ovid MEDLINE and then translated to and executed across four additional databases: Scopus, CINAHL, PsycInfo, and the Cochrane Library, from their inception to November 8, 2023. The full search strategies for all databases can be found in (Appendix 1).

Study selection

Search results from all databases were compiled and deduplicated in by ER [18], then imported into Covidence [19] for additional deduplication and screening. Records were screened independently by two individual reviewers each against the eligibility criteria (CC, JF, MF, and YW). Conflicts were resolved through a tie-breaking vote from AN or SP. Full texts were then screened independently by two individual reviewers each and conflicts resolved in the same fashion as described for the title/abstract screening. Because individual screening tools could appear in several reports, an additional screening step (by AN) was added by choosing from the set of full-text inclusions one validation study for each identified measurement tool. At this point, tools were excluded if they were unavailable due to cost to obtain survey or if the survey was written in a language other than English or Spanish. Data extraction was then conducted on this final set of included reports. The screening and inclusion process is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. PRISMA Diagram.

Data collection

Data related to the screening and assessment of chronic pain, opioid use and trauma was extracted using the data-charting form developed in Covidence. Data from included studies was systematically charted using the data charting form developed in Covidence. Information on authorship, article type, population, title, and topic of outcome measurement tool(s) identified in the study and population target for measurement tool(s) were recorded on this form. Copies of measurement tool(s) for each of the included studies were obtained and information in measurement tool(s) instructions and scoring type, and item/questions were entered into the extraction form.

Data synthesis

Information on the data charting form was organized and summarized with respect to the outcome measurement tool topic(s): chronic pain, behavioral health/trauma, analgesic usage, or some combination of these three main topics.

Results

The initial search revealed 10,777 articles with 204 duplicates resulting in 10,573 distinct potential articles. The article titles and abstracts were then screened against inclusion and exclusion criteria by two reviewers, resulting in 1,167 articles for full-text review. Out of the 1,167 full-text studies, 665 studies met inclusion criteria. A secondary full-text assessment was performed to assess specific screening tools against inclusion and exclusion criteria and to exclude duplicate screening tools, resulting in 39 studies for data extraction (Figure 1). During this de-duplication process, studies were excluded for the following reasons: 1) outcome measurement does directly involve single topic or any combination of chronic pain, behavioral health/trauma and analgesic use, 2) survey unavailable (e.g. cost to obtain survey, original survey written in language other than Spanish or English), 3) wrong population (e.g. adolescents, post-surgical, pain sequelae to other known disorders or surgery, behavioral health/trauma sequelae or as part of diagnosis for behavioral disorder (e.g. diagnostic for depression, anxiety), and 4) objective measurement tool used in combination with data from larger inventory.

Out of the final 39 articles, 31 tools were identified for assessment of chronic pain, 8 for the detection of opioid/medication misuse, and 7 for the evaluation of trauma. Totals add up to more than 39, as some tools addressed two topics within one tool such as opioids and chronic pain. A summary of these tools is shown in Table 2.

|

Article |

Tool Included |

Domain Assessed |

|

Jones 2014 [20] |

Brief Risk Interview (BRI) |

Analgesic usage |

|

Jones 2014 [20] |

Opioid Risk Tool (ORT) |

Analgesic usage |

|

Jones 2014 [20] |

Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain-Revised (SOAPP-R) |

Analgesic usage |

|

Carmona 2018 [21] |

Adjective Rating Scale for Withdrawal (ARSW) |

Analgesic usage |

|

Carmona 2023[22] |

Prescription Opioid Misuse Index (POMI) |

Analgesic usage |

|

Martel 2014 [23] |

Opioid Misuse Measure |

Analgesic usage |

|

Buelow 2009 [24] |

Revised, shortened version of the Pain Medication Questionnaire (PMQ) |

Analgesic usage |

|

Castillo 2010 [25] |

Severity-of-Dependence-Scale SDS |

Analgesic usage |

|

Barke 2015 [26] |

Psychological Inflexibility in Pain Scale (PIPS) |

Chronic Pain |

|

Barke 2015 [26] |

Psychological Inflexibility in Pain Scale (PIPS) |

Chronic Pain |

|

Bianchini 2014 [27] |

Pain Disability Index (PDI) |

Chronic Pain |

|

Nicholas 2015 [28] |

Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (PSEQ) 10-item |

Chronic Pain |

|

Nicholas 2015 [28] |

PSEQ-2 |

Chronic Pain |

|

McCracken 2004 [29] |

Chronic Pain Acceptance Questionnaire (CPAQ) |

Chronic Pain |

|

Wassinger 2021 [30] |

Orebro Musculoskeletal Pain Questionnaire (OMPQ) |

Chronic Pain |

|

Bruehl 2016 [31] |

Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) |

Chronic Pain |

|

Richards 1982 [32] |

UAB Pain Behavior Scale |

Chronic Pain |

|

Burton 1999 [33] |

Basic Personality Inventory (BPI) |

Chronic Pain |

|

Burton 1999 [33] |

Multidimensional Pain Inventory (MPI) |

Chronic Pain |

|

VanWyngaarden 2019 [34] |

Targeted Treatment Back Screening Tool (SBT) |

Chronic Pain |

|

VanWyngaarden 2019 [34] |

Optimal Screening for Prediction of Referral and Outcome Yellow Flag (OSPRO-YF) |

Chronic Pain |

|

Carlsson 1984 [35] |

Pain questionnaire evaluation |

Chronic Pain |

|

AlBanyan 2021[36] |

Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ) |

Chronic Pain |

|

Waterman 2010 [37] |

Pain Quality Assessment Scale (PQAS) |

Chronic Pain |

|

Mittinty 2022 [38] |

Fear of Pain Questionnaire (FPQ-9) |

Chronic Pain |

|

Lippe 2016 [39] |

Pain Disability Questionnaire |

Chronic Pain |

|

Cuesta-Vargas 2020 [40] |

The Fear-Avoidance Components Scale (FACS) |

Chronic Pain |

|

Kleinstauber 2023 [41] |

Biopsychosocial Model of Chronic Pain (PEB) Scale |

Chronic Pain |

|

Neblett 2015 [42] |

Tampa Scale for kinesiophobia (TSK) |

Chronic Pain |

|

Gagnon 2023 [43] |

Patient-Specific Functional Scale (PSFS) |

Chronic Pain |

|

Larsen 1997 [44] |

Pain Anxiety Symptoms Scale (PASS) |

Chronic Pain |

|

McCracken 2010 [45] |

Brief Pain Response Inventory (BPRI) |

Chronic Pain |

|

VonKorff 2019 [46] |

Graded Chronic Pain Scale-Revised |

Chronic Pain |

|

Enebo 1998 [47] |

The Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale |

Chronic Pain |

|

Roelofs 2003 [48] |

pain vigilance and awareness questionnaire (PVAQ) |

Chronic Pain |

|

Freynhagen 2006 [49] |

painDETECT questionnaire (PD-Q) |

Chronic Pain |

|

Main 1983 [50] |

Modified Somatic Perceptions Questionnaire |

Chronic Pain |

|

Ruscheweyh 2012 [51] |

Pain Sensitivity Questionnaire |

Chronic Pain |

|

Torrance 2009 [52] |

36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36) |

Chronic pain |

|

Ball 2015 [53] |

Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12) scores (physical and mental components) |

Trauma |

|

Geisser 1997 [54] |

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) |

Trauma |

|

Geisser 1997 [54] |

Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D) |

Trauma |

|

Cann 2011 [55] |

Event Related Rumination Inventory (ERRI) |

Trauma |

|

Green 2006 [56] |

Stressful Life Events Screening Questionnaire (SLESQ) |

Trauma |

|

Chavez 2017 [57] |

The AC-OK Screen for Co-Occurring Disorders |

Trauma |

|

deBont 2015 [58] |

Trauma Screening Questionnaire |

Trauma |

Discussion

Chronic pain management in PLWH presents unique challenges due to the interplay of biological, psychological, and social factors. Beyond the physical manifestations of HIV, individuals may also contend with comorbidities, including substance use disorders, mental health conditions, and histories of trauma. These factors not only contribute to the experience of chronic pain but also complicate its management. For instance, PLWH may experience heightened levels of pain due to neuropathy associated with HIV [59], while also struggling with psychological distress stemming from stigma, discrimination, and past traumatic experiences.

The scoping review identified a wide range of measurement tools validated for screening chronic pain, trauma, and analgesic use in the adult population. The extensive search process and strict eligibility criteria ensured all included studies are relevant to the research question. However, our results indicated a scarcity of screeners for detection of analgesic medication misuse and psychological trauma among patients. This gap in available resources poses significant difficulty for healthcare providers striving to deliver comprehensive and individualized interventions to effectively manage chronic pain in PLWH.

It is also noted that while the existing tools cover a range of psychosocial constructs related to chronic pain, including catastrophizing, vigilance, and fear avoidance behaviors, there remains a notable need to place trauma assessment tools unto further psychometric property analysis. This rigorous evaluation would not only further ensure their validity but also their sensitivity and specificity in capturing the interplay between psychological trauma and chronic pain experiences.

Implementing validated screening tools for chronic pain, trauma, and analgesic use in clinical settings holds significant promise for improving patient outcomes. Therefore, the next phase of research should focus on developing new tools that address the unique needs of PLWH with chronic pain, utilizing applicable items included in the current screeners summarized above. It is also essential to consider practical considerations such as ease of use, accessibility, and applications across different healthcare disciplines to ensure the effective implementation of these tools in routine practice. Collaborative efforts between researchers, clinicians, and affected communities will be crucial in driving forward this agenda and ultimately improving the quality of care for PLWH living with chronic pain.

Conclusion

This scooping review provides a comprehensive overview of the validated measurement tools available for screening chronic pain, trauma, and analgesic use among adults, with a specific focus on PLWH. The findings highlight the diversity of existing tools and emphasize the importance of multidimensional assessment approaches that address the complex connections between chronic pain, trauma, and opioid use.

The development of a multidimensional screening tool tailored to the needs of PLWH is warranted. This tool would allow healthcare providers to identify and address the unique challenges faced in this population with the goal of improving patient outcomes and quality of life. Continued research and collaboration in this research are required for advancing the field of chronic pain management regarding HIV care.

Limitations

Several limitations should be noted. First, despite the rigorous search strategies used, it is possible that some relevant studies may have been missed. Of note are studies that were published in languages other than English or Spanish. Additionally, the inclusion criteria focused on only measurement tools which have been validated. This potentially excludes studies that could be valuable but are utilizing unvalidated tools. These limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings of this scoping review.

Funding

Center for AIDS Research at Emory University. Opportunity Award Grant. Painful to Discuss: The Intersection of Chronic Pain, Mental Health and Analgesic Use Among People with HIV. (P30AI050409).

Data Availability Statement

The data that supports the findings of this study are available on public domains that include the peer reviewed articles included in the review. These data were derived from the resources available in Ovid MEDLINE and then translated to and executed across four additional databases: Scopus, CINAHL, PsycInfo, and the Cochrane. These are all public domains.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

2. Silvis J, Rowe CL, Dobbins S, Haq N, Vittinghoff E, McMahan VM, et al. Engagement in HIV care and viral suppression following changes in long-term opioid therapy for treatment for chronic pain. AIDS Behav. 2022 Oct;26(10):3220-30.

3. Merlin JS, Westfall AO, Raper JL, Zinski A, Norton WE, Willig JH, et al. Pain, mood, and substance abuse in HIV: implications for clinic visit utilization, antiretroviral therapy adherence, and virologic failure. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012 Oct 1;61(2):164-70.

4. Pullen SD, Del Rio C, Brandon D, Colonna A, Denton M, Ina M, et al. Associations between chronic pain, analgesic use and physical therapy among adults living with HIV in Atlanta, Georgia: a retrospective cohort study. AIDS Care. 2020 Jan;32(1):65-71.

5. Pullen SD, Nuñez MA, Bennett S, Brown W, Cronin C, Fleischer M, et al. Painful to Discuss: The Intersection of Chronic Pain, Mental Health, and Analgesic Use among People with HIV. J AIDS HIV Treat. 2023;5(1):46-53.

6. Surratt HL, Kurtz SP, Levi-Minzi MA, Cicero TJ, Tsuyuki K, O'Grady CL. Pain treatment and antiretroviral medication adherence among vulnerable HIV-positive patients. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2015 Apr;29(4):186-92.

7. Pullen SD, Del Rio C, Brandon D, Colonna A, Denton M, Ina M, et al. An Innovative Physical Therapy Intervention for Chronic Pain Management and Opioid Reduction Among People Living with HIV. Biores Open Access. 2020 Dec 8;9(1):279-85.

8. Edelman EJ, Rentsch CT, Justice AC. Polypharmacy in HIV: recent insights and future directions. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2020 Mar;15(2):126-33.

9. Strang J, Volkow ND, Degenhardt L, Hickman M, Johnson K, Koob GF, et al. Opioid use disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020 Jan 9;6(1):3.

10. Cunningham CO. Opioids and HIV Infection: From Pain Management to Addiction Treatment. Top Antivir Med. 2018 Apr;25(4):143-6.

11. Basukala B, Rossi S, Bendiks S, Gnatienko N, Patts G, Krupitsky E, et al. Virally Suppressed People Living with HIV Who Use Opioids Have Diminished Latency Reversal. Viruses. 2023 Feb 1;15(2):415.

12. Nadal KL, Erazo T, King R. Challenging definitions of psychological trauma: Connecting racial microaggressions and traumatic stress. Journal for Social Action in Counseling & Psychology. 2019 Dec 12;11(2):2-16.

13. Sales JM, Swartzendruber A, Phillips AL. Trauma-Informed HIV Prevention and Treatment. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2016 Dec;13(6):374-82.

14. Remien RH, Stirratt MJ, Nguyen N, Robbins RN, Pala AN, Mellins CA. Mental health and HIV/AIDS: the need for an integrated response. AIDS. 2019 Jul 15;33(9):1411-20.

15. Salahuddin D, Conti T. Trauma and Behavioral Health Care for Patients with Chronic Pain. Prim Care. 2022 Sep;49(3):415-23.

16. Idalski Carcone A, Coyle K, Gurung S, Cain D, Dilones RE, Jadwin-Cakmak L, et al. Implementation Science Research Examining the Integration of Evidence-Based Practices Into HIV Prevention and Clinical Care: Protocol for a Mixed-Methods Study Using the Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, and Sustainment (EPIS) Model. JMIR Res Protoc. 2019 May 23;8(5):e11202.

17. Mak S, Thomas A. An Introduction to Scoping Reviews. J Grad Med Educ. 2022 Oct;14(5):561-64.

18. The Endnote Team. Endnote 21. Philadelphia, PA, United states: Clarivate Analytics; 2013.

19. Covidence systematic review software [Internet]. Melbourne, Australia: Veritas Health Innovation; Available from: http://www.covidence.org.

20. Jones T, Lookatch S, Grant P, McIntyre J, Moore T. Further validation of an opioid risk assessment tool: the Brief Risk Interview. J Opioid Manag. 2014 Sep-Oct;10(5):353-64.

21. Coloma-Carmona A, Carballo JL, Rodríguez-Marín J, van-der Hofstadt CJ. The Adjective Rating Scale for Withdrawal: Validation of its ability to assess severity of prescription opioid misuse. Eur J Pain. 2019 Feb;23(2):307-15.

22. Coloma-Carmona A, Carballo JL. Assessing opioid abuse in chronic pain patients: Further validation of the Prescription Opioid Misuse Index (POMI) using item response theory. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 2024 Oct;22(5):2962-76.

23. Martel MO, Dolman AJ, Edwards RR, Jamison RN, Wasan AD. The association between negative affect and prescription opioid misuse in patients with chronic pain: the mediating role of opioid craving. J Pain. 2014 Jan;15(1):90-100.

24. Buelow AK, Haggard R, Gatchel RJ. Additional validation of the pain medication questionnaire in a heterogeneous sample of chronic pain patients. Pain Pract. 2009 Nov-Dec;9(6):428-34.

25. Iraurgi Castillo I, González Saiz F, Lozano Rojas O, Landabaso Vázquez MA, Jiménez Lerma JM. Estimation of cutoff for the Severity of Dependence Scale (SDS) for opiate dependence by ROC analysis. Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2010 Sep-Oct;38(5):270-7

26. Barke A, Riecke J, Rief W, Glombiewski JA. The Psychological Inflexibility in Pain Scale (PIPS) - validation, factor structure and comparison to the Chronic Pain Acceptance Questionnaire (CPAQ) and other validated measures in German chronic back pain patients. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015 Jul 28;16(1):171.

27. Bianchini KJ, Aguerrevere LE, Guise BJ, Ord JS, Etherton JL, Meyers JE, et al. Accuracy of the Modified Somatic Perception Questionnaire and Pain Disability Index in the detection of malingered pain-related disability in chronic pain. Clin Neuropsychol. 2014;28(8):1376-94.

28. Nicholas MK, McGuire BE, Asghari A. A 2-item short form of the Pain Self-efficacy Questionnaire: development and psychometric evaluation of PSEQ-2. J Pain. 2015 Feb;16(2):153-63.

29. McCracken LM, Vowles KE, Eccleston C. Acceptance of chronic pain: component analysis and a revised assessment method. Pain. 2004 Jan;107(1-2):159-66.

30. Wassinger CA, Sole G. Agreement and screening accuracy between physical therapists ratings and the Ӧrebro Musculoskeletal Pain Questionnaire in screening for risk of chronic pain during Musculoskeletal evaluation. Physiother Theory Pract. 2022 Nov;38(13):2949-55.

31. Bruehl S, Ohrbach R, Sharma S, Widerstrom-Noga E, Dworkin RH, Fillingim RB, et al. Approaches to Demonstrating the Reliability and Validity of Core Diagnostic Criteria for Chronic Pain. J Pain. 2016 Sep;17(9 Suppl):T118-31.

32. Richards SJ, Nepomuceno C, Riles M, Suer Z. Assessing pain behavior: the UAB Pain Behavior Scale. Pain. 1982;14(4):393-8.

33. Burton HJ, Kline SA, Hargadon R, Cooper BS, Shick RD, Ong-Lam MC. Assessing patients with chronic pain using the basic personality inventory as a complement to the multidimensional pain inventory. Pain Research and Management. 1999;4(3):121-9.

34. Van Wyngaarden JJ, Noehren B, Archer KR. Assessing psychosocial profile in the physical therapy setting. Journal of Applied Biobehavioral Research. 2019 Jun;24(2):e12165.

35. Carlsson AM. Assessment of chronic pain. II. Problems in the selection of relevant questionnaire items for classification of pain and evaluation and prediction of therapeutic effects. Pain. 1984 Jun;19(2):173-84.

36. Al Banyan M, Al Shareef S, Aljayar DMA, Abothenain FF, Khaliq AMR, Alrayes H, et al. Assessment of pain in patients with primary immune deficiency. Saudi J Anaesth. 2021 Oct-Dec;15(4):377-82.

37. Waterman C, Victor TW, Jensen MP, Gould EM, Gammaitoni AR, Galer BS. The assessment of pain quality: an item response theory analysis. J Pain. 2010 Mar;11(3):273-9.

38. Mittinty MM, Santiago PHR, Jamieson L. Assessment of Pain-Related Fear in Indigenous Australian Populations Using the Fear of Pain Questionnaire-9 (FPQ-9). Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 May 20;19(10):6256.

39. Lippe B, Gatchel RJ, Noe C, Robinson R, Huber E, Jones S. Comparative ability of the pain disability questionnaire in predicting health outcomes. Journal of Applied Biobehavioral Research. 2016 Jun;21(2):63-81.

40. Cuesta-Vargas AI, Neblett R, Gatchel RJ, Roldán-Jiménez C. Cross-cultural adaptation and validity of the Spanish fear-avoidance components scale and clinical implications in primary care. BMC Fam Pract. 2020 Feb 27;21(1):44.

41. Kleinstäuber M, Garland EL, Sisco-Taylor BL, Sanyer M, Corfe-Tan J, Barke A. Endorsing a Biopsychosocial Perspective of Pain in Individuals With Chronic Pain: Development and Validation of a Scale. Clin J Pain. 2024 Jan 1;40(1):35-45.

42. Neblett R, Hartzell MM, Mayer TG, Bradford EM, Gatchel RJ. Establishing clinically meaningful severity levels for the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia (TSK-13). Eur J Pain. 2016 May;20(5):701-10.

43. Gagnon CM, Yuen M, Palmer K. An Exploration of Physical Therapy Outcomes and Psychometric Properties of the Patient-Specific Functional Scale After an Interdisciplinary Pain Management Program. Clin J Pain. 2023 Dec 1;39(12):663-71.

44. Larsen DK, Taylor S, Asmundson GJ. Exploratory factor analysis of the Pain Anxiety Symptoms Scale in patients with chronic pain complaints. Pain. 1997 Jan;69(1-2):27-34.

45. McCracken LM, Vowles KE, Zhao-O'Brien J. Further development of an instrument to assess psychological flexibility in people with chronic pain. J Behav Med. 2010 Oct;33(5):346-54.

46. Von Korff M, DeBar LL, Krebs EE, Kerns RD, Deyo RA, Keefe FJ. Graded chronic pain scale revised: mild, bothersome, and high-impact chronic pain. Pain. 2020 Mar 1;161(3):651-61.

47. Enebo BA. Outcome measures for low back pain: Pain inventories and functional disability questionnaires. Chiropractic Technique. 1998;10:27-33.

48. Roelofs J, Peters ML, McCracken L, Vlaeyen JWS. The pain vigilance and awareness questionnaire (PVAQ): further psychometric evaluation in fibromyalgia and other chronic pain syndromes. Pain. 2003 Feb;101(3):299-306.

49. Freynhagen R, Baron R, Gockel U, Tölle TR. painDETECT: a new screening questionnaire to identify neuropathic components in patients with back pain. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006 Oct;22(10):1911-20.

50. Main CJ. The Modified Somatic Perception Questionnaire (MSPQ). J Psychosom Res. 1983;27(6):503-14.

51. Ruscheweyh R, Verneuer B, Dany K, Marziniak M, Wolowski A, Çolak-Ekici R, et al. Validation of the pain sensitivity questionnaire in chronic pain patients. Pain. 2012 Jun;153(6):1210-8.

52. Torrance N, Smith BH, Lee AJ, Aucott L, Cardy A, Bennett MI. Analysing the SF-36 in population-based research. A comparison of methods of statistical approaches using chronic pain as an example. J Eval Clin Pract. 2009 Apr;15(2):328-34.

53. Ball K, MacPherson C, Hurowitz G, Settles-Reaves B, DeVeaugh-Geiss J, Weir S, et al. M3 checklist and SF-12 correlation study. Best Practices in Mental Health. 2015 Mar 1;11(1):83-9.

54. Geisser ME, Roth RS, Robinson ME. Assessing depression among persons with chronic pain using the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale and the Beck Depression Inventory: a comparative analysis. Clin J Pain. 1997 Jun;13(2):163-70.

55. Cann A, Calhoun LG, Tedeschi RG, Triplett KN, Vishnevsky T, Lindstrom CM. Assessing posttraumatic cognitive processes: the Event Related Rumination Inventory. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2011 Mar;24(2):137-56.

56. Green BL, Chung JY, Daroowalla A, Kaltman S, Debenedictis C. Evaluating the cultural validity of the stressful life events screening questionnaire. Violence Against Women. 2006 Dec;12(12):1191-213.

57. Chavez LM, Shrout PE, Wang Y, Collazos F, Carmona R, Alegría M. Evaluation of the AC-OK mental health and substance abuse screening measure in an international sample of Latino immigrants. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017 Nov 1;180:121-8.

58. de Bont PA, van den Berg DP, van der Vleugel BM, de Roos C, de Jongh A, van der Gaag M, et al. Predictive validity of the Trauma Screening Questionnaire in detecting post-traumatic stress disorder in patients with psychotic disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2015 May;206(5):408-16.

59. Schütz SG, Robinson-Papp J. HIV-related neuropathy: current perspectives. HIV AIDS (Auckl). 2013 Sep 11;5:243-51.