Introduction

Chronic cancer-related pain, according to the latest International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11), is defined as “chronic pain caused by the primary cancer itself or metastases (chronic cancer pain) or its treatment (chronic post-cancer treatment pain)” [1].

It is a world-wide problem with a prevalence ranging from 40% after curative treatment to 66% in advanced, metastatic, or terminal disease. In 38% of cases, it was described as moderate to severe [2].

Fatigue, insomnia, anxiety, and depression are all concomitant and pain-related symptoms in patients with cancer, so they are called symptom clusters [3] which dramatically impact on the patient’s overall quality of life and significantly affect perceived sense of well-being as well as physical and social functions [4]. These symptom clusters can also be more debilitating for the patients than the single symptom, potentiating each other and making their clinical management complex and challenging. Almost 50% of cancer patients nowadays report their pain as inadequately controlled [5,6]. In addition, several barriers still exist in pain management, related to the lack of an adequate knowledge and education by all the figures involved (i.e., physician, patients, nurses, and pharmacists), and the adequate drugs prescription, the fear of aberrant drugseeking behaviors, the presence of regulatory constraints, the socio-economic and cultural disparities: all these factors can further contribute to suboptimal pain identification and treatment [7].

To overcome this problem, several expert panels have recently published guidelines and recommendations to improve diagnosis and treatment in cancer pain patients, based on the best scientific available evidence [8-10]. All these documents underline the importance of an adequate and comprehensive pain assessment that should never forget that pain is a complex multidimensional experience, involving sensory-discriminative, cognitive, emotional, and behavioral dimensions. Therefore, not only intensity of pain must be assessed, but also its duration (i.e., continuous, intermittent, or transient pain) and location (diffuse, localized, overall pain), its etiology and pathogenesis (neuropathic, nociceptive, mixed pain). Cancer related pain can arise from the mechanical or chemical activation and sensitization of nociceptors (i.e., nociceptive pain), caused by tissue compression or cancer cells mediators release which can also be amplified by immune cells recruitment (i.e., inflammatory pain).

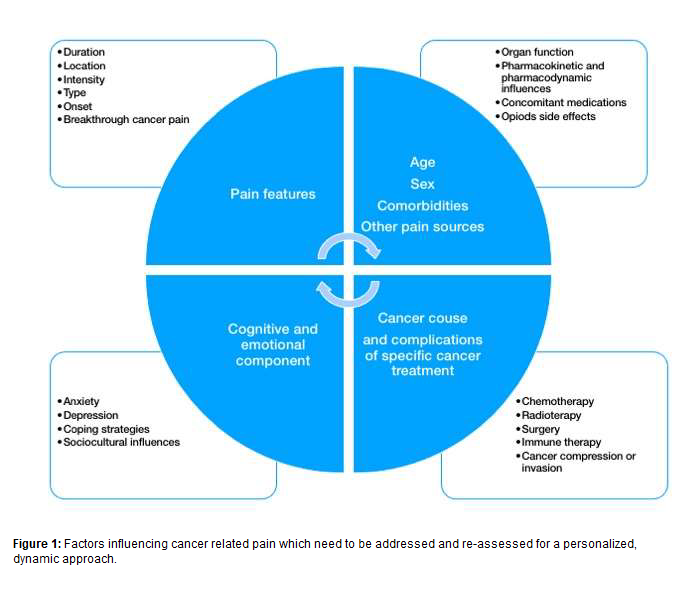

It can also be caused by a damage or a disease affecting the nervous system (i.e., neuropathic pain), such as root compression or chemotherapy-induced neuropathy, but can also recognize, as chronic non cancer pain, a mixed phenotype, in which different pathogenetic mechanisms can overlap each other (such as bone metastasis) [11,12]. However, differently from chronic non cancer pain, cancer pain is more frequently associated with affective, motivational and cognitive component [11)]. Other aspects such as sex, age, co-morbidities, anxiety and depression, the impact on quality of life, sociocultural influence and coping strategies, should be addressed to better understand the effect of “total pain” to the whole person (Figure 1) [13].

Inside the New Approach for Cancer-Related Pain

Cancer-related pain can have a multimorphic behavior, since its etiology, pathophysiology, temporality, and location may vary during its natural course. Comorbidities, mood, and adaptive strategies but also cancer treatments and their related adverse effects can amplify this dynamic behavior [14]. Pain assessment and treatment should dynamically match the multimorphic cancer related pain and should be multimodal to offer a targeted patient-centered approach. In this personalized strategy, several tools can be used simultaneously to better describe pain. Global self-rating scales such as the numerical or verbal rating scale and multidimensional questionnaires, like the McGill Pain (MPQ) and Brief Pain Inventory (BPI), can be adopted according to patient cognitive status [15]. Moreover, neuropathic component must be documented, as well as the impact on quality of life. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS), that provides comprehensive and rapid assessment symptom clusters, can be useful for a comprehensive assessment of cancer patients [16].

In addition, physicians should investigate for basal and breakthrough cancer pain (BTcP) [17] in order to plan an adequate basal pain control as well as rescue doses for transient exacerbations of pain. An accurate characterization of BTcP is crucial, therefore the Breakthrough Pain Assessment Tool has been proposed to improve its diagnosis and treatment. The right formulation (i.e., rapid onset opioids), the right route (buccal vs nasal), the preemptive use in case of predictable episodes, and the correct titration strategy [18] are pivotal for a tailored treatment of BTcP episodes.

Every therapeutic strategy, starting from the definition of a personalized pain goal, should be shared with the patients and their caregiver [19] and should be reassessed in terms of analgesia, side effects, function and quality of life.

The WHO Ladder and Its Limits

The main accepted algorithm for cancer pain management still remains the WHO three-step analgesic ladder, which suggests non-opioids, weak opioids, and strong opioids according to pain intensity, associated or not with adjuvants [20]. This strategy, however, raised some criticisms by several pain therapists [21] since its “static” nature does not combine with the real-world experience and the multifaceted and evolving nature of cancer pain. Therefore, a multimodal approach that considers pharmacological and non-pharmacological strategies (such as psychological support and physiotherapy) [22] but also combined interventional techniques (such as infiltrative therapy and neuromodulation) has been proposed [23]. In addition, several different approaches to opioid prescribing, not in accordance with the historical WHO ladder, have been proposed: strong opioids at low doses can be used as first-line treatment, assuring an adequate pain control with similar incidence of adverse events in comparison to weak opioids [24]. The implementation of the “opioid science” is still needed, as a recent Delphi survey underlined [25]. A deep knowledge of opioids’ pharmacology is crucial. The oral route with long-acting opioids remains the first choice, while the transdermal one should be considered in those patients who cannot swallow or have an impaired gastrointestinal function or ileostomy. Short acting opioids can be useful for a rapid daily dose titration, while after titration, the combination of a long and a short acting formulation of opioid is essential to obtain a more flexible and effective treatment plan [7,10].

Also, opioid rotation or route rotation, in case of poor pain control despite appropriate dose escalations or unsafe drugdrug interactions, are suggested [26] and well accepted in real world pain practice [21]. In patients not responding to the best combined available therapy or who develop untreatable side effects from conventional medical management, an intrathecal drug infusion should be considered, since this approach can allow a safe and rapid control of refractory cancer pain, with high levels of patient satisfaction [26-30]. Very recent guidelines confirmed this figure, with a level of recommendation IA, but also recommend the adoption of other techniques such as celiac plexus neurolysis in pancreatic cancer, radiation therapy in painful metastatic bone disease or vertebral augmentation in symptomatic vertebral compression from spinal metastases [30].

Two other points should be remembered when prescribing an opioid: the risk of abuse and the management of adverse events. Although the risk of abuse and misuse is low in oncological patients, screening tools are recommended, not to limit opioid prescription, but to identify patients at highest risk for misuse (i.e., younger patients with a prior history of abuse or with aberrant behaviors) and to tailor the pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic options in this special population [31].

Also, the monitoring of adverse events is of paramount importance in order to improve treatment adherence. One of the most common side effects of opioid therapy is opioid-induced bowel disfunction (OIBD) with a prevalence that reaches 90% in cancer patients [32]. The presence of OIBD negatively impacts patients’ quality of life, increasing patient’s distress, anxiety, and depression [33] and therefore requires clinical awareness and strict clinical monitoring. The correct management of OIBD starts from a careful clinical evaluation, since in cancer patients many causes can promote constipation, and a correct diagnosis, using simple, assessment tools like the Bowel Function Index (BFI) [34] is pivotal. Moreover, an individualized therapy that combines education of the patient, correction of all worsening factors such as fluid intake and electrolyte abnormalities, combination of different type of laxatives and the use of newer agents like peripherally acting mu-opioid receptor agonists (PAMORAs) are recommended [35].

Adjuvants and Complementary Pain Therapy

A dynamic treatment of cancer related pain in a multimodal way cannot ignore other approaches, both pharmacological and non-pharmacological.

As previously stated, the neuropathic component, related both to cancer invasion or secondary to chemotherapy, radiotherapy or surgery, should always be considered and treated accordingly. The prevalence of neuropathic pain is around 40% among cancer patients [36], and, in the case of chemotherapy-induced neuropathy, it involves almost 70% of patients receiving anticancer drugs [37]. The mechanisms proposed are alteration of axonal transport, changes in ion channel and receptor activities, neuronal injury and inflammation, oxidative stress, and each chemotherapeutic shows its specific target. However, no specific drug is recommended for chemotherapy-induced neuropathy prevention, therefore the mainstay of treatment still remain anticonvulsants (gabapentinoids) or antidepressant (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressant) local anesthetics or corticosteroids [10,15]. A personalized pain control strategy passes through a combined therapy, considering synergistic effects of these drugs on pain but also possible, preventable adverse events, such as sedation, dizziness, or drug to drug interaction (i.e., cytochrome inhibition).

In recent years, other integrative therapies, such as cognitive therapy [38] and acupuncture [39] are emerging as an add-on useful option in cancer patients, while data on cannabis are still conflicting. Preclinical data showed promising evidence, but human studies did not confirm that the addition of cannabis or cannabinoids is effective to treat cancer pain [40]. Even if direct cannabinoids effect on cancer pain is not clear, their usefulness in treating some symptom cluster like anorexia or depression can make them an adjuvant option that needs to be further investigated [41].

Suggestions and Conclusions

The multimorphic presentation of cancer pain and its strict link with other symptom clusters such as anxiety, depression and insomnia dramatically impact on patients’ quality of life. Therefore, a holistic biopsychosocial approach is essential to pain assessment and management. This requires an interdisciplinary team management, composed by physicians, nurses, medical social workers, physiotherapists, pharmacists, and psychologists, who all together work out the best pain treatment plan for every patient. The challenge for the future will be the real-life application of this integrated care model to proactively improve the management of chronic cancerrelated pain.

References

2. Evenepoel M, Haenen V, De Baerdemaecker T, Meeus M, Devoogdt N, Dams L, et al. Pain prevalence during cancer treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2022 Mar; 63(3):e317-e335.

3. Dong ST, Costa DS, Butow PN, Lovell MR, Agar M, Velikova G, et al. Symptom clusters in advanced cancer patients: an empirical comparison of statistical methods and the impact on quality of life. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2016 Jan 1; 51(1):88-98.

4. Charalambous A, Giannakopoulou M, Bozas E, Paikousis L. Parallel and serial mediation analysis between pain, anxiety, depression, fatigue and nausea, vomiting and retching within a randomised controlled trial in patients with breast and prostate cancer. BMJ Open. 2019 Jan 1; 9(1):e026809.

5. Neufeld NJ, Elnahal SM, Alvarez RH. Cancer pain: a review of epidemiology, clinical quality and value impact. Future Oncology. 2017 Apr; 13(9):833-41.

6. Marinangeli F, Saetta A, Lugini A. Current management of cancer pain in Italy: Expert opinion paper. Open Medicine. 2022 Jan 1; 17(1):34-45.

7. Scarborough BM, Smith CB. Optimal pain management for patients with cancer in the modern era. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2018 May; 68(3):182-96.

8. Lara-Solares A, Ahumada Olea M, Basantes Pinos AD, Bistre Cohén S, Bonilla Sierra P, Duarte Juárez ER, et al. Latin-American guidelines for cancer pain management. Pain Management. 2017 Jul; 7(4):287-98.

9. Swarm RA, Paice JA, Anghelescu DL, Are M, Bruce JY, Buga S, et al. Adult cancer pain, version 3.2019, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2019 Aug 1; 17(8):977-1007.

10. Fallon M, Giusti R, Aielli F, Hoskin P, Rolke R, Sharma M, et al. Management of cancer pain in adult patients: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. Annals of Oncology. 2018 Oct 1;29:iv166-91.

11. Cohen SP, Vase L, Hooten WM. Chronic pain: an update on burden, best practices, and new advances. The Lancet. 2021 May 29; 397(10289):2082-97.

12. Zajączkowska R, Kocot-Kępska M, Leppert W, Wordliczek J. Bone pain in cancer patients: mechanisms and current treatment. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2019 Jan; 20(23):6047.

13. Mehta A, Chan LS. Understanding of the concept of” total pain”: a prerequisite for pain control. Journal of Hospice & Palliative Nursing. 2008 Jan 1; 10(1):26-32.

14. Minello C, George B, Allano G, Maindet C, Burnod A, Lemaire A. Assessing cancer pain—the first step toward improving patients’ quality of life. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2019 Aug; 27(8):3095-104.

15. Magee D, Bachtold S, Brown M, Farquhar-Smith P. Cancer pain: where are we now?. Pain Management. 2019 Jan; 9(1):63-79.

16. Hui D, Bruera E. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System 25 years later: past, present, and future developments. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2017 Mar 1; 53(3):630-43.

17. Davies AN, Dickman A, Reid C, Stevens AM, Zeppetella G. The management of cancer-related breakthrough pain: recommendations of a task group of the Science Committee of the Association for Palliative Medicine of Great Britain and Ireland. European Journal of Pain. 2009 Apr 1; 13(4):331-338.

18. Vellucci R, Fanelli G, Pannuti R, Peruselli C, Adamo S, Alongi G, et al. What to do, and what not to do, when diagnosing and treating breakthrough cancer pain (BTcP): expert opinion. Drugs. 2016 Mar; 76(3):315-30.

19. Hui D, Bruera E. A personalized approach to assessing and managing pain in patients with cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2014 Jun 1; 32(16):1640.

20. Stjernswärd J. WHO cancer pain relief programme. Cancer Surveys. 1988 Jan 1; 7(1):195-208.

21. Varrassi G, De Conno F, Orsi L, Puntillo F, Sotgiu G, Zeppetella J, et al. Cancer pain management: an Italian Delphi survey from the Rational Use of Analgesics (RUA) Group. Journal of Pain Research. 2020 May 8; 13:979-986.

22. Feng B, Hu X, Lu WW, Wang Y, Ip WY. Are mindfulness treatments effective for pain in cancer patients? A systematic review and metaanalysis. European Journal of Pain. 2022 Jan; 26(1):61-76.

23. Cuomo A, Bimonte S, Forte CA, Botti G, Cascella M. Multimodal approaches and tailored therapies for pain management: the trolley analgesic model. Journal of Pain Research. 2019 Feb 19; 12:711-714.

24. Caraceni A, Hanks G, Kaasa S, Bennett MI, Brunelli C, Cherny N, et al. Use of opioid analgesics in the treatment of cancer pain: evidencebased recommendations from the EAPC. The Lancet Oncology. 2012 Feb 1; 13(2):e58-68.

25. Varrassi G, Coluzzi F, Guardamagna VA, Puntillo F, Sotgiu G, Vellucci R. Personalizing cancer pain therapy: insights from the rational use of analgesics (RUA) group. Pain and Therapy. 2021 Jun; 10(1):605-17.

26. Webster LR, Fine PG. Review and critique of opioid rotation practices and associated risks of toxicity. Pain Medicine. 2012 Apr 1; 13(4):562-70.

27. Alicino I, Giglio M, Manca F, Bruno F, Puntillo F. Intrathecal combination of ziconotide and morphine for refractory cancer pain: a rapidly acting and effective choice. Pain. 2012 Jan 1; 153(1):245-9.

28. Puntillo F, Giglio M, Preziosa A, Dalfino L, Bruno F, Brienza N, et al. Triple intrathecal combination therapy for end-stage cancer-related refractory pain: a prospective observational study with two-month follow-up. Pain and Therapy. 2020 Dec; 9(2):783-92.

29. Perruchoud C, Dupoiron D, Papi B, Calabrese A, Brogan SE. Management of Cancer-Related Pain With Intrathecal Drug Delivery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Clinical Studies. Neuromodulation. 2022 Jan 21; S1094-7159(21)06969-5.

30. Aman MM, Mahmoud A, Deer T, Sayed D, Hagedorn JM, Brogan SE, Singh V, Gulati A, Strand N, Weisbein J, Goree JH. The American Society of Pain and Neuroscience (ASPN) best practices and guidelines for the interventional management of cancer-associated pain. J Pain Res. 2021 Jul 16; 14:2139-2164.

31. Anghelescu DL, Ehrentraut JH, Faughnan LG. Opioid misuse and abuse: risk assessment and management in patients with cancer pain. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2013 Aug 1; 11(8):1023-1031.

32. ALMouaalamy N. Opioid-Induced Constipation in Advanced Cancer Patients. Cureus. 2021 Apr 9; 13(4):e14386.

33. Argoff CE. Opioid-induced constipation: a review of healthrelated quality of life, patient burden, practical clinical considerations, and the impact of peripherally acting μ-opioid receptor antagonists. The Clinical Journal of Pain. 2020 Sep; 36(9):716-722.

34. Sarrió RG, Calsina-Berna A, García AG, Esparza-Miñana JM, Ferrer EF, Porta-Sales J. Delphi consensus on strategies in the management of opioid-induced constipation in cancer patients. BMC palliative care. 2021 Dec; 20(1):1-8.

35. Crockett SD, Greer KB, Heidelbaugh JJ, Falck-Ytter Y, Hanson BJ, Sultan S. American Gastroenterological Association Institute guideline on the medical management of opioid-induced constipation. Gastroenterology. 2019 Jan 1; 156(1):218-26.

36. Yoon SY, Oh J. Neuropathic cancer pain: prevalence, pathophysiology, and management. The Korean journal of internal medicine. 2018 Nov; 33(6):1058-1069.

37. Sałat K. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: part 1—current state of knowledge and perspectives for pharmacotherapy. Pharmacological Reports. 2020 Jun; 72(3):486-507.

38. Park S, Sato Y, Takita Y, Tamura N, Ninomiya A, Kosugi T, et al. Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for Psychological Distress, Fear of Cancer Recurrence, Fatigue, Spiritual Well-Being, and Quality of Life in Patients With Breast Cancer—A Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2020 Aug 1; 60(2):381-9.

39. Yang J, Wahner-Roedler DL, Zhou X, Johnson LA, Do A, Pachman DR, et al. Acupuncture for palliative cancer pain management: systematic review. BMJ supportive & palliative care. 2021 Sep 1; 11(3):264-70.

40. Chung M, Kim HK, Abdi S. Update on cannabis and cannabinoids for cancer pain. Current Opinion in Anesthesiology. 2020 Dec 1; 33(6):825-31.

41. Turgeman I, Bar-Sela G. Cannabis for cancer–illusion or the tip of an iceberg: A review of the evidence for the use of Cannabis and synthetic cannabinoids in oncology. Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs. 2019 Mar 4; 28(3):285-96.