Abstract

A retrospective analytical study about the efficacy of treatment and secondary antifungal prophylaxis of histoplasmosis in AIDS patients is presented. Seventy-seven medical records were studied of which fifty patients were male. The median age of the cases was 44 years (range from 24 to 75). In 17 cases (19.5%) the diagnosis of HIV infection and histoplasmosis were simultaneously obtained. Only 8 out of 60 cases (13.8%) with positive HIV serology were under antiretroviral treatments. The median T CD4+cell count of 77 patients was 54/µl (range 0-196). Seventy-six cases presented a subacute disseminated histoplasmosis with involvement of several organs and one was diagnosed as a symptomatic primary infection with bilateral severe pneumonia. The diagnosis of histoplasmosis was confirmed by the isolation of Histoplasma capsulatum in cultures and/or by the visualization of typical yeast-like elements in microscope biopsy studies or cytodiagnosis of lesions in 66 cases and by skin and serology tests with histoplasmin in the patient with a symptomatic primary infection. The initial treatment with amphotericin B or itraconazole was effective in 84.4% of cases. 64% of patients discharged after ending the initial treatment continued their follow-up in our Unit. But only 22 cases (28%) completed the control and achieved the necessary conditions to discontinue the antifungal prophylaxis. Itraconazole at a dose of 200 mg/day was indicated in all cases as secondary antifungal prophylaxis together with different antiretroviral drugs. This treatment was interrupted in all the cases that presented two CD4+ cell count >150/µl, had an undetectable HIV viral load and no signs or symptoms of progressive histoplasmosis. In 64% of patients the conditions for antifungal interruption were achieved in 12 months of prophylaxis. This group of patients was controlled for 12 to 24 months after antifungal discontinuation and no relapses were observed.

Initial treatment and secondary antifungal prophylaxis are highly effective in AIDS-related histoplasmosis. New antiretroviral drugs seem to get a faster restoration of immunity and a high proportion of the studied cases abandoned follow-up before ending clinical controls.

Keywords

Histoplasmosis; Histoplasma capsulatum; AIDS-related infections; Systemic endemic mycoses; Opportunistic mycoses

Introduction

Classic histoplasmosis is a systemic endemic mycosis due to the dimorphic fungus Histoplasma capsulatum var. capsulatum. This microorganism lives as mold in rich nitrogen soil in temperate and humid regions. Microconidiae and small hyphae are the infective elements. They enter through the respiratory tract and, in the pulmonary alveoli they transform into intracellular yeasts inside the macrophages. The majority of the infections is asymptomatic or presents a mild and selflimited respiratory illness. People with chronic respiratory diseases or cell-mediated immunity deficiencies may suffer progressive pulmonary or progressive disseminated histoplasmosis (PDH) with a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations [1-3].

PDH is an opportunistic infection frequently observed in HIV-positive patients with T CD4+cell count <100/μl, who live in endemic areas like Latin America [4,5]. The majority of these cases in Argentina have been registered in big cities such as Córdoba, Rosario and Buenos Aires. In the Francisco Javier Muñiz Infectious Diseases Hospital of Buenos Aires City 2.5% of cases treated for AIDS related opportunistic infections suffer subacute PDH. It is the second life-threatening mycosis associated with AIDS after meningeal cryptococcosis [4,6]. The Mycology Unit of Muñiz Hospital has been studying treatments and secondary prophylaxis of AIDS-related PDH for more than three decades. Two studies which allowed establishing the efficacy of the initial antifungal treatment of this mycosis as well as the parameters for discontinuing the secondary antifungal prophylaxis were published in 2004 and 2017 [7,8]. The results observed in these two studies were similar to those presented in investigations published by other authors [9-11]. Histoplasmosis treatment has not changed since 2015, but several antiretroviral drugs have been incorporated to AIDS therapy armamentarium.

The aim of this paper is to present the results of a new retrospective analytical study about the efficacy and safe interruption of secondary prophylaxis in cases of AIDSrelated histoplasmosis treated in the Mycology Unit from 2015 to 2017.

Materials and Methods

A retrospective analytical study of the medical records of 87 patients suffering from progressive histoplasmosis who were treated in the Mycology Unit from January 2015 to July 2017 was carried out.

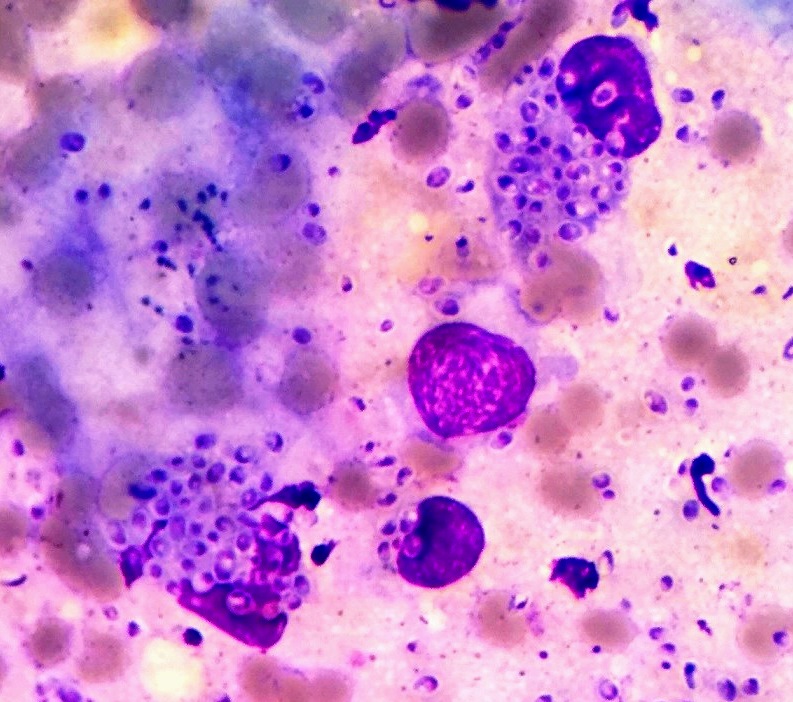

All the patients with AIDS-related histoplasmosis were included. The diagnosis of histoplasmosis was confirmed by the isolation of H. capsulatum in cultures and/or by the visualization of typical yeast-like elements in microscope biopsy studies or cytodiagnosis of lesions (Figures 1-3). The mycology studies were performed according to the techniques published by The Mycology Laboratories Network of the Buenos Aires City Government [12]. Specific serology tests were also performed using an exoantigen of H. capsulatum yeast form prepared according to the procedure published in another paper [13]. The serology tests performed were immunodiffusion and counterimmunolectrophoresis.

Figure 1: Skin papules located on the arm in a patient with PDH associated with AIDS.

Figure 3: Cytodiagnosis of a skin lesion smear stained with Giemsa, optic microscope 1,000X, showing numerous yeast like elements of H. capsulatum inside

macrophages.

Patients with disseminated histoplasmosis with nonreactive HIV serology tests were excluded from the study.

Results

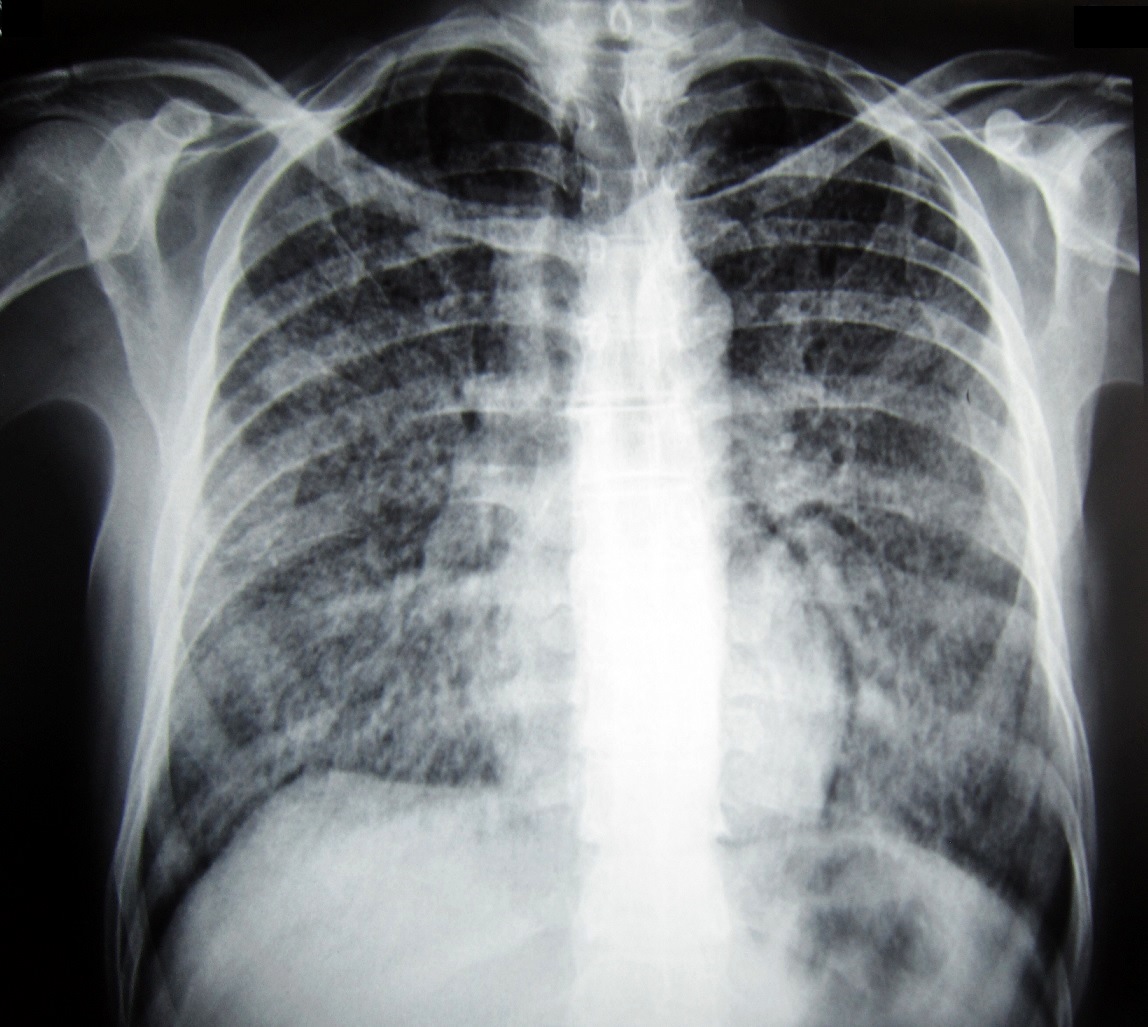

Seventy-seven cases (88.5%) were included in the study; 10 were excluded due to non- reactive HIV serology tests. Fifty patients were male and the median age was 44 years (range from 24 to 75). In 17 cases (19.5%) the diagnosis of HIV infection and histoplasmosis were simultaneously obtained. Only 8 out of 60 cases (13.8%) with positive HIV serology were under antiretroviral treatments at admission. The median TCD4 cell count of 77 patients was 54/μl (range 0-196). Seventy six cases presented a subacute PDH with involvement of several organs and one was diagnosed as a symptomatic primary infection with bilateral severe pneumonia. He acquired the infection during an excavation in an old historical building in Buenos Aires downtown. He was under antiretroviral treatment at the time of histoplasmosis diagnosis and his CD4+cell count was 196/μL. The diagnosis of the mycosis was based on the results of histoplasmin skin test and immunodiffusion with a specific antigen; both turned positive during convalescence. He showed rapid clinical improvement to amphotericin B deoxycholate. Two cases with subacute disseminated histoplasmosis presented immune restoration inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) a few days after starting antiretroviral therapy.

The clinical samples which allowed getting the diagnosis of histoplasmosis are presented in Table 1. Cytodiagnosis studies of skin or mucosal lesions and blood cultures were the most efficient clinical samples 57/77 (74%).

| Clinical Samples | N: 77 |

|---|---|

| Skin or mucous membrane cytodiagnosis | 40 |

| Blood culture | 17 |

| Bronchoalveolar lavage | 6 |

| Lymph node biopsy | 4 |

| Tonsil biopsy | 1 |

| Lip biopsy | 1 |

| Palate biopsy | 1 |

| Skin biopsy | 1 |

| Bone marrow biopsy | 1 |

| Bone marrow aspiration | 2 |

| Serology | 2 |

| Esputum | 1 |

Sixty-six patients received amphotericin B deoxycholate intravenously at variable doses from 0.3mg/Kg/day to 0.7mg/Kg/day as initial treatment. The remaining 11 cases were treated with itraconazole by oral route at a daily dose of 600mg for the first three days and then, 400mg/ day for 3 or 6 months, according to the severity of clinical manifestations and the patient’s outcome. Amphotericin B was applied for 14 or 21 days and, after amphotericin B discontinuation, itraconazole at a daily dose of 400mg was orally administered for 3 to 6 months. After ending the initial part of the treatment the secondary antifungal prophylaxis began. All patients received itraconazole at a daily dose of 200mg orally for approximately one year. Antifungal prophylaxis was interrupted when the patients presented two CD4+ cell counts above 150/μl, their HIV viral loads were undetectable (<20 RNA copies) and they did not have any signs or symptoms of active histoplasmosis.

Twelve patients (15.6%) died during the initial treatment due to the fatal evolution of the mycosis or to comorbidities. Forty-two out of sixty-five (64.6%) cases discharged from our hospital after ending the first part of treatment continued the follow-up in the Mycology Unit. Only 22 of them (28%) completed the antifungal prophylaxis and their controls in our Unit, 3 abandoned treatments and controls and the remaining cases continued their follow up in other health institutions.

The following anti-retroviral treatments (ART) were indicated: 19 cases received emtricitabine (FTC)+tenofovir (TDF)+efavirenz (EFV); 8 patients were treated with darunavir-ritonavir (DRV/r)+TDF-FTC; 5 received raltegravir (RAL)+FTC-TDF, 4 were treated with atazanavir-ritonavir (ATZ/r)+FTC-TDF; 2 received lamivudine (3TC)+abacavir (ABC)+EFV; two dolutegravir (DTG)+FTC-TDF: 1 DTG+3TC+TDF and 1 was treated with fosamprenavir-ritonavir (FPV/r)+FTC+TDF.

The antifungal secondary prophylaxis duration and the antiretroviral drugs used are summarized in Table 2.

| Antiretroviral employed | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antifungal prophylaxis time |

FTC-TDF-EFV N: 11 |

DRV/r+TDF+FTC N: 5 |

ATV/r+FTC+TDF N: 2 |

RAL+FTC+TDF N: 3 |

DTG+FTC+TDF N: 1 |

| 12 months | 5 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| 15 months | 4 | 1 | |||

| 18 months | 2 | ||||

As can be seen in Table 2 fifteen patients (68%) were able to discontinue the secondary prophylaxis with itraconazole in twelve months. The other cases needed 15 or 18 months to reach this goal and no failure was observed. The antiretroviral treatments were well tolerated.

In one case the antifungal prophylaxis with itraconazole was interrupted after 6 months. This patient was the one who presented a pulmonary symptomatic primary infection and had a high CD4+ cell count (196/μl) at the beginning of the treatment.

All the cases continued their follow-up for 12 to 24 months after discontinuation of prophylaxis in our Unit and no relapses were detected.

Discussion

The results observed in this study were similar to those presented in our former publications and agree with those observed by other authors [2,7-10].

The initial step of the treatment was effective in 65 out of 77 cases (84.4%), a better performance than the one observed in 2017 (78.2%). These results are similar to those presented in studies carried out in USA; and do not agree with the high mortality rate detected in Guatemala and French Guiana [14,15]. In this part of the treatment amphotericin B was the drug most frequently indicated: 85.5% of the cases. Amphotericin B is considered the drug of choice, but the frequent observation of side effects, especially nephrotoxicity, sometimes prevents its use [2,4]. Liposomal amphotericin B is indicated in these cases. According to the Guide for the treatment and prophylaxis of AIDS-related opportunistic infections of the AIDS Division of the Muñiz Hospital [16] itraconazole was indicated as initial treatment in those cases with moderate symptoms, without hypoalbuminemia, digestive or neurological disorders. Another situation frequently observed in our institution that prevents the use of itraconazole is comorbidity with tuberculosis. In this case the indication of rifampicin has priority and amphotericin B is indicated [4,16]. Other triazoles like voriconazole and posaconazole have been applied in the treatment of histoplasmosis but the clinical experience is scarce; they should be indicated only in special cases [17]. Fluconazole is not active against Histoplasma capsulatum even in Histoplasma meningitis, where it is less efficient than itraconazole [2].

Frequently antiretroviral treatment (ART) is indicated two weeks after beginning antifungal treatment in order to avoid a possible IRIS presentation, especially in those cases suffering from central nervous system or digestive tract involvement. The most severe complications of an early beginning of ART will be intracranial hypertension or gut perforation [6,9,10].

Some pharmacokinetic characteristics and drug interaction of antiretroviral drugs should be considered when they are indicated together with itraconazole. When protease inhibitors are applied it should be taken into account that these drugs reduce the enzymatic activities of CYP450 3A4 and this may increase serum itraconazole levels. This will require the periodic control of itraconazole serum concentration or the reduction of the daily dose administered to 300mg [18-20]. Integrase inhibitors like RAL and DTG do not have drug interactions with itraconazole, but these drug associations produce a quick restoration of immunity which may give way to severe IRIS [20]. The association of cobicistat with some protease inhibitor like darunavir or Integrase inhibitorlike elvitegravir in the same pill may decrease the enzymatic activities of CYP4503A4, which increases both itraconazole and antiviral drugs blood levels [19,20].

As in our previous studies, antifungal secondary prophylaxis and ART showed a high efficacy in the posttreatment control of AIDS-related histoplasmosis. The new antiretroviral drugs seem to produce a faster restoration of immunity than the drugs we used back in 2017 study [8]. 68% of patients were in condition to discontinue the antifungal prophylaxis in 12 months. These findings agree with those observed by other authors [2,9,10,11,21].

The detection of H. capsulatum galactomannan in urine is important in monitoring histoplasmosis treatment results. It was included in other studies as a parameter to decide the discontinuation of antifungal prophylaxis [2,4,9-11,22]. The Mycology Unit experience has been recently published [23]. This test was not systematically performed in the present study.

Primary antifungal prophylaxis was not considered necessary in our Hospital due to the relatively low incidence of this opportunistic mycosis as well as its low mortality rate (15.6%). In some endemic zones like French Guiana, Guatemala and Illinois State (USA) primary antifungal prophylaxis is recommended in HIV positive cases with CD4+ cell counts <100/μl. when the incidence of histoplasmosis in health institutions is greater than 10% of the patients admitted for HIV-related opportunistic infections [2,24].

Initial treatment failure was due to the acute course of histoplasmosis or comorbidities and the mortality rate was lower when compared with other studies [14,15].

As in our previous presentations we have observed a high frequency of abandonment of medical control, probably due to the low socio-economic and cultural level of the majority of patients.

Conflict of Interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

2. Wheat LJ, Azar MM, Bahr NC, Spec A, Relich RF, Hage C. Histoplasmosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2016 Mar;30(1):207-27.

3. Couppié P, Herceg K, Bourne-Watrin M, Thomas V, Blanchet D, Alsibai KD, et al. The Broad Clinical Spectrum of Disseminated Histoplasmosis in HIV-Infected Patients: A 30 Years’ Experience in French Guiana. Journal of Fungi. 2019 Dec;5(4):115.

4. Negroni R. Micosis asociadas al SIDA. Benetucci J. Y colaboradores. SIDA y enfermedades asociadas. Fundación de Ayuda al Inmunodeficiente (FUNDAI). Buenos Aires. 2001:301-24.

5. World Health Organization. Guidelines for Diagnosing and Managing Disseminated Histoplasmosis among People Living with HIV. 2020.

6. Corti M, Negroni R, Esquivel P, Villafañe MF. Histoplasmosis diseminada en pacientes con SIDA: análisis epidemiológico, clínico, microbiológico e inmunológico de 26 pacientes. Enf Emerg. 2004;6(1):8-15.

7. Negroni R, Helou SH, López Daneri G, Robles AM, Arechavala AI, Bianchi MH. Interrupción de la profilaxis secundaria antifúngica en la histoplasmosis asociada al sida. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2004;21:75-8.

8. Negroni R, Messina F, Arechavala A, Santiso G, Bianchi M. Eficacia del tratamiento y de la profilaxis antifúngica secundaria en la histoplasmosis asociada al sida. Experiencia del Hospital de Infecciosas Francisco J. Muñiz, de la ciudad de Buenos Aires. Revista Iberoamericana de Micología. 2017 Apr 1;34(2):94-8.

9. Myint T, Leedy N, Villacorta Cari E, Wheat LJ. HIV associated with AIDS: current perspective. HIV/AIDS Research and Palliative Care. 2020; 12: 113-25.

10. Azar M, Hage CA. The diagnosis and management of histoplasmosis. Clin Chest Med. 2014; 38: 403-415.

11. Myint T, Anderson AM, Sanchez A, Farabi A, Hage C, et.al. Histoplasmosis in patients with Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS). Mulcenter study of outcome and factors associated with relapse. Medicine 2014; 93:11-18.

12. Guelfand L, Cataldi S, Arechavala A, Perrone M. Manual práctico de micologia médica. Acta Bioquim Clin Latinoam, 2015, Suplemento 1.

13. Arechavala A, Eiguchi K, Iovannitti C, Negroni R. Utilidad del enzimoinmunoensayo para el serodiagnóstico de la histoplasmosis asociada al SIDA. Rev. argent. micol. 1997:24-8.

14. Nacher M, Adenis A, Mc Donald S, Do Socorro Mendonca Gomes M, Singh S, Lopes Lima I, et al. Disseminated histoplasmosis in HIV-infected patients in South America: a neglected killer continues on its rampage. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013 Nov 21;7(11):e2319.

15. Samayoa B, Roy M, Cleveland AA, Medina N, Lau- Bonilla D, Scheel CM, et al. High mortality and coinfection in a prospective cohort of human immunodeficiency virus/ acquired immune deficiency syndrome patients with histoplasmosis in Guatemala. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2017 Jul 12;97(1):42-8.

16. Valerga M, Viola C. Histoplasmosis diseminada. In: Corti ME, Metta HA. Guía para la prevención y el tratamiento de las infecciones oportunistas en pacientes con enfermedad HIV/SIDA. División B HIV/SIDA Hospital de Infecciosa Francisco J. Muñiz Gobierno de la Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, 2008; 91-94.

17. Restrepo A, Tobón A, Clark B, Graham DR, Corcoran G, et al. Salvage treatment of histoplasmosis with posaconazole. Journal of Infection. 2007 Apr 1;54(4):319- 27.

18. VIH drug interactions website: https://www.drugs. com/drug_interactions.html

19. Cottrell ML, Hadzic T, Kashuba AD. Clinical pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic and drug-interaction profile of the integrase inhibitor dolutegravir. Clinical pharmacokinetics. 2013 Nov 1;52(11):981-94.

20. Dodds Ashley E. Pharmacology of azole antifungal agents. In: Ghannoum M, Perfect J. Antifungal Therapy; Second Edition. 2019; Boca Raton: CRC Press.

21. López Daneri AG, Arechavala AI, Iovannitti CA, Mujica MT. Histoplasmosis diseminada en pacientes con HIV/SIDA en Buenos Aires. Medicina (Buenos Aires) 2016; 76: 332-337.

22. Cáceres DH, Samayoa BE, Medina NG, Tobón AM, Guzmán BJ, Mercado D, et al. Multicenter validation of commercial antigenuria reagents to diagnose progressive disseminated histoplasmosis in people living with HIV/ AIDS in two Latin American countries. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2018 Jun 1;56(6).

23. Arechavalia A, Bianchi M, Messina F, Romero M, Negroni R, Santiso G. Usefulness of an elisa kit for the detection of Histoplasma capsulatum antigen in patients with aids. Revista de Patologia Tropical/Journal of Tropical Pathology. 2017 Jun 14;46(2):135-45.

24. Nacher M, Adenis A, Basurko C, Vantilcke V, Blanchet D, Aznar C, et al. Primary prophylaxis of disseminated histoplasmosis in HIV patients in French Guiana: arguments for cost effectiveness. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene. 2013 Dec 4;89(6):1195-8.