Abstract

Numerous autoimmune diseases, which currently affect a sizable portion of the global population, are driven by aberrant autoantigen-specific T cell responses that result in tissue destruction and loss of function. Current therapeutics for autoimmunity are non-curative and rely on global immunosuppression, leaving patients vulnerable to opportunistic infections and malignancies. An ideal approach would suppress autoantigen-specific T cell responses while leaving the remainder of the immune system intact. Recently, Tremain et al. have developed a therapeutic strategy that suppresses autoantigen-specific T cell responses by targeting autoantigens to the liver’s innate tolerogenic environment. In their approach, antigens are modified with synthetic polymeric glycosylations that target internalizing C-type lectins on the surface of liver antigen presenting cells. Autoantigens targeted to liver antigen presenting cells are presented to autoantigen-specific T cells in the presence of immunosuppressive signals that drive T cells to undergo apoptosis, adopt a state of anergy, or differentiate into T regulatory cells—a subset of T cells that can provide durable suppression of autoantigen-specific T cell responses. This mini-review describes the mechanisms by which glycopolymer-mediated targeting of autoantigens to the liver establishes autoantigen-specific immunological tolerance, summarizes the various findings of the recent publications that utilize this platform, and discusses potential therapeutic applications for treating autoimmune diseases and allergies.

Keywords

Antigen-specific tolerance, Glycopolymers, Glycosylation, Hepatic delivery, Liver, Targeted delivery, Tolerogenic microenvironment

Main Text

Overview of immunological tolerance

The mechanisms of immunological tolerance restrict the immune system's ability to mount a response against self-antigens and innocuous foreign ones. These mechanisms can be divided into two broad categories: central tolerance and peripheral tolerance. Central tolerance, mediated by the thymus, involves the clonal deletion of CD4/CD8 double-positive T cells with a high affinity for self-antigen peptides presented via the major histocompatibility complex (MHC). Inversely, T cells that are unable to recognize MHC-presented self-antigen do not receive further maturation signals, leading to their death by neglect [1,2]. Only T cells with low or intermediate affinity for self-antigen presented via MHC undergo positive selection and mature into CD4 or CD8 single-positive T cell populations. Specifically, T cells with intermediate affinity for self-antigen peptides presented in the context of MHCII begin to upregulate expression of the forkhead box P3 (FOXP3) transcription factor as well as CD25, ultimately maturing into antigen-specific thymus-derived regulatory T cells (tTregs) [1,2]. These tTregs can tamp down aberrant immune activation in a variety of ways, including through the secretion of immunosuppressive cytokines like interleukin 10 (IL-10) and transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β), direct lysis of effector target cells through the release of cytotoxic granules comprised of granzymes and perforin, metabolic disruption of effector T cell activity via CD25-mediated preferential consumption of IL-2, and inhibition of antigen-presenting cell (APC) function through cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) and programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) signaling [1-3]. Holistically, these tTregs play a vital role in maintaining durable immunological homeostasis and preventing the development of an autoimmune response, particularly through the suppression of autoreactive T cells that were able to avoid negative selection and subsequent clonal deletion in the thymus.

Immunological homeostasis is also modulated by the various mechanisms of peripheral tolerance. Primarily, when non-Treg CD4+ T cells encounter antigen presented on MHCII in the context of IL-10, TGF-β, or retinoic acid in secondary lymphoid organs (SLOs) or in specific tissues such as the liver or gut, they can differentiate into peripheral regulatory T cells (pTregs) [4]. Like tTregs, pTregs are identified via the expression of CD25 and FOXP3 and can perform the same immunosuppressive functions. In fact, due to their ability to be induced on-site rather than in the thymus, pTregs are typically more abundant than tTregs in the gut and liver. Peripheral tolerance also relies heavily on the induction of anergy amongst effector T cell populations. Antigen recognition by previously activated T cells without sufficient costimulatory signals results in impaired T cell IL-2 production, transforming the cell into an inactive, anergic state where it no longer responds to antigenic stimulation [5].

Therapeutics for autoimmune disease

Despite the presence of these assorted tolerogenic mechanisms to maintain homeostasis, dysregulation in these processes can occur in a variety of ways, thereby resulting in autoimmune diseases [6,7]. Many biologic therapeutics have been developed to tamp down autoimmunity and restore a homeostatic state; however, most of these therapies focus on global immunosuppression, thereby putting the patient at risk of contracting an illness or developing an opportunistic infection [8]. Targeted biologic strategies for treating autoimmune diseases—like infliximab, an anti-TNF antibody—can modulate aberrant immune responses more specifically, but their effects are transient, and the drugs are often immunogenic [9-11]. To address these shortcomings, a new generation of therapeutics has been created that elicit long-lasting, antigen-specific tolerance by suppressing the T cells that drive autoimmunity, thereby circumventing the need for global immunosuppression. Antigen-specific tolerance can be induced in a variety of ways, including utilizing antigen-loaded tolerogenic dendritic cells (tolDCs), ex vivo expansion and reinfusion of autologous antigen-specific Treg cells, and infusion of antigen-specific chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) Treg cells [12-14]. However, each of these approaches requires retrieval, manipulation, and reinfusion of patient cells, rendering this process cumbersome, highly technical, and expensive, reducing patient accessibility [15,16]. To combat this, other strategies, including nanoparticle encapsulation of autoantigens [17], in vivo conjugation of antigens to erythrocytes [18], and ex vivo conjugation of autoantigens to glycopolymers [19-21] have been developed. Techniques such as these merely require a simple intravenous infusion, which dramatically reduces cost and system complexity. Moreover, these in situ targeting approaches deliver autoantigens to specific organs such as the liver or spleen to induce autoantigen-specific tolerogenic responses, further increasing therapeutic potential.

Liver-targeted antigen delivery

Amongst these methods, liver-targeted antigen delivery is particularly promising because it capitalizes upon the liver’s inherent pro-tolerogenic environment. Since the liver receives constant exposure to food antigens and commensal bacterial antigens from the gut via the portal vein, it has evolved to maintain a tolerogenic microenvironment that prevents the development of immune responses to these harmless antigens [22,23]. The APCs in the liver, including Kupffer cells (KCs), liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSECs), and hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) express much lower levels of T cell-activating costimulatory molecules (e.g., CD80 and CD86) than APCs found in the secondary lymphoid organs [24]. In addition, KCs, LSECs, and HSCs continually express TGF-β and IL-10, which promote tTreg induction, reduce CD28 signaling, and directly inhibit the expression of effector T cell lineage-defining transcription factors such as GATA-3 and T-bet, thereby inducing tolerogenic T cell education [25-27]. Thus, antigen recognition by autoantigen-specific T cells in the liver results in the induction of autoantigen-specific tTregs while other autoantigen-specific effector T cell subtypes are rendered anergic. This organ-wide quiescence drives the development of oral tolerance to ingested food antigens, thereby acting as a preventative measure against allergies [28]. In addition to maintaining tolerance to gut-derived antigens, the liver’s ability to clear autoantigen-loaded apoptotic cells and cellular debris is central to maintaining immune homeostasis. The clearance of apoptotic cells by hepatic APCs is mediated by C-type lectin receptors that recognize N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) and N-acetylglucosamine (GluNAc) residues, which are exposed during the apoptotic breakdown of cells [29,30]. Upon internalization, autoantigens from apoptotic cells and debris are processed and presented by hepatic APCs to autoantigen-specific T cells, resulting in tolerogenic T cell responses [24]. Since this C-type lectin-mediated internalization and tolerogenic processing is based solely on the presence of GalNAc or GluNAc residues, it is possible to generate these same tolerogenic T cell responses via synthetic decoration of foreign antigens with these same glycosylation patterns.

Glycopolymer-mediated prophylactic tolerance induction

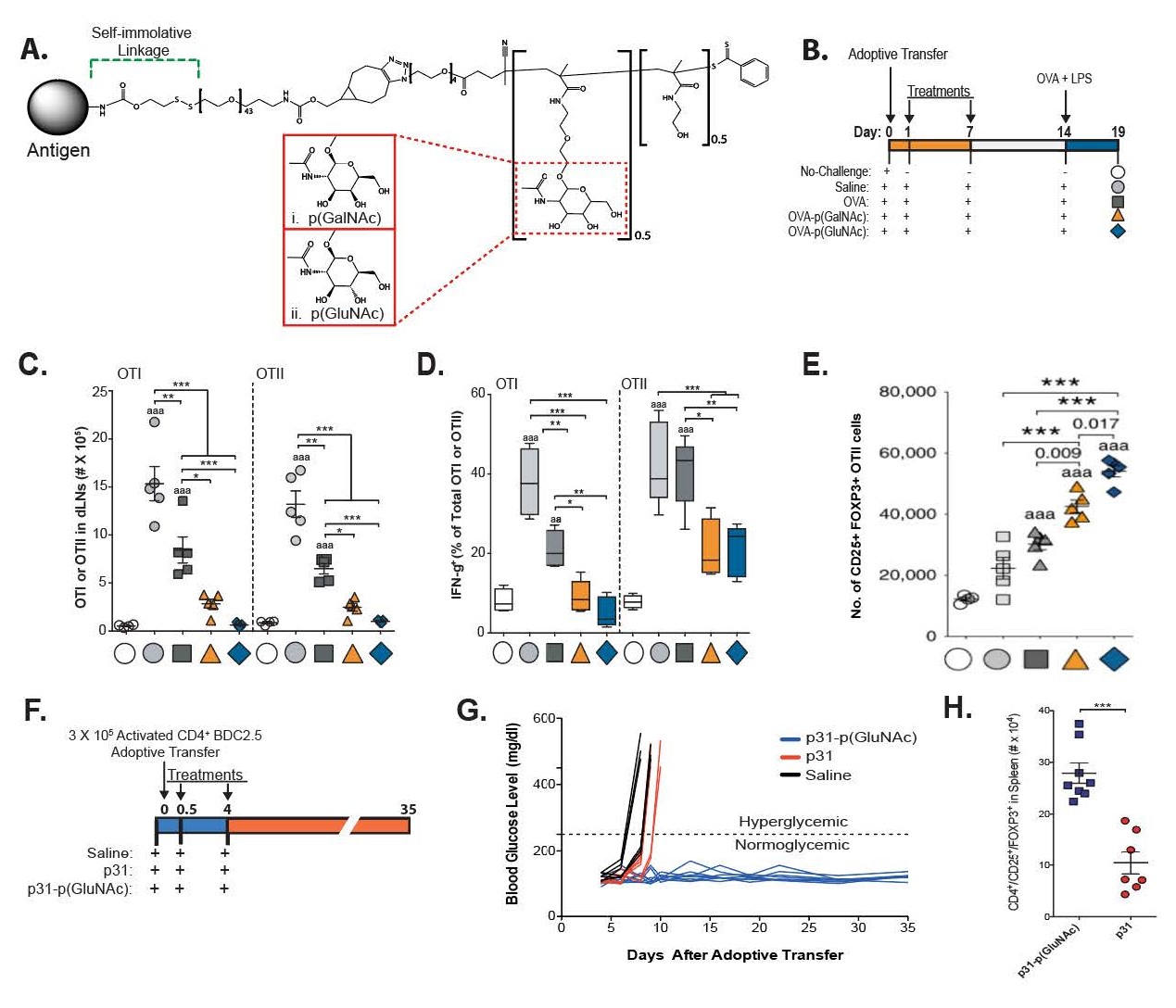

In 2019, after observing this tendency of hepatic APCs to recognize and internalize GalNAc and GluNAc, Wilson et al. developed strategies to synthetically glycosylate antigens with these residues to increase uptake, presentation and, ultimately, tolerance to the autoantigens they selected [21]. By initially modifying the model antigen ovalbumin (OVA) with a self-immolating linker attached to a random copolymer composed of monomers decorated with either β-linked GalNAc (p(GalNAc)) or β-linked GluNAc (p(GluNAc)) and a biologically inert comonomer, through terminal amine conjugation, the authors were able to engineer a reduction-sensitive system to release the protein in its native form after cellular uptake (Figure 1A)—thereby replicating the natural release of autoantigens after apoptotic clearance of cells in the liver. After tail vein injection of these OVA-conjugated polymers, targeted delivery to the liver was confirmed via whole-organ fluorescence imaging. Antigen presentation by hepatic APCs was confirmed by flow cytometry staining for the MHC-peptide complex of the OVA-derived peptide SIINFEKL presented on the MHCI molecule H2-Kb, as well as increased proliferation of liver OTI and OTII cells. After glycopolymer administration, these OTI and OTII cells also displayed higher levels of annexin-V binding, a marker of apoptosis, and higher surface expression of both PD-1 and CTLA-4, thereby implying tolerogenic T cell education. To test the effects of these OVA-conjugated glycopolymers at preventing the development of an antigen-specific immune response, C57BL/6 mice were adoptively transferred with OTI and OTII cells, after which they were treated with OVA-p(GalNAc) or OVA-p(GluNAc), followed by an intradermal challenge of OVA and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Figure 1B). Glycopolymer-treated mice were demonstrated to have fewer OTI and OTII effector cells in the draining lymph nodes and spleen than mice treated with only OVA, as well as decreased IFNγ production (Figures 1C and 1D).

Figure 1: Chemical structure and prophylactic effects of glycopolymer-conjugated antigen delivery system. A. Chemical structure of glycopolymer conjugates. Antigens are tethered to a glycopolymer containing either p(GalNAc) or p(GluNAc) residues via a self-immolative linker that is capable of releasing the antigen in its native form upon intracellular reduction. B. Dosing regimen for OVA-p(GalNAc) or OVA-p(GluNAc) treatment after OTI/OTII adoptive transfer to examine OVA-specific immune responses. On days 1 and 7 after adoptive transfer, mice were treated with either 10 μg of unmodified OVA, OVA-p(GalNAc), or OVA-p(GluNAc). After coadministration of OVA with LPS on day 14, mice were sacrificed on day 19 to analyze OVA-specific cell responses. C. Total numbers of OTI and OTII cells in draining lymph nodes after glycopolymer-conjugated antigen administration. D. Percentage of IFNγ-producing OTI and OTII cells, as determined via flow cytometry. E. Treg numbers in draining lymph nodes on day 19 after glycopolymer-conjugated antigen administration, as measured by flow cytometry. F. Dosing regimen for p31-p(GluNAc) after adoptive transfer of activated diabetogenic BDC2.5 splenocytes into NOD/SCID mice. G. Blood glucose levels of p31-p(GluNAc)-treated mice, as compared to saline and p31, for several days after adoptive transfer. H. Overall number of Treg cells in spleen between treatment groups. Statistical significance in C-E was determined via one-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni correction. Statistical significance in H was determined via a two-tailed student’s t-test. Bolded numbers and the letter “a” indicate comparisons with the unchallenged group (aaa: P ≤ 0.001), while numbers/stars above horizontal error bars are indicative of comparisons between the indicated groups (***: P ≤ 0.001). Data is displayed as means ± S.E.M.

A dramatically increased proportion of OTII Treg cells compared to untreated controls was also observed (Figure 1E). To verify the tolerogenic effects of the cytokines produced by these OTII Tregs, the authors depleted both IL-10 and TGF-β wherein the generation of these OTII Tregs was lost, thereby demonstrating that both IL-10 and TGF-β were necessary to achieve this tolerogenic phenotype (data not shown). This increase in Treg cells was maintained over time, even 4 weeks after the final administration of the OVA-glycopolymer conjugates. The authors also demonstrated equivalent prophylactic tolerance induction in a BDC2.5 T cell adoptive transfer mouse model of type 1 diabetes. After an adoptive transfer of activated BDC2.5 splenocytes into nonobese diabetic-severe combined immunodeficiency (NOD/ SCID) mice, treatments of either saline, peptide mimotope p31 (p31), or p31-p(GluNAc) were administered twice on day 0 with an additional dose on day 4 (Figure 1F). Whereas all mice treated only with the peptide mimotope p31, which induces the development of diabetes in the model via activation of autoreactive T cells against islet β cells, develop diabetes within 10 days of peptide administration, all mice treated with p31-p(GluNAc) maintained normal blood sugar levels for 5 weeks, the duration of the experiment (Figure 1G). As in the OVA experiments, these results were also determined to be due, at least in part, to antigen-specific Treg induction, based on the elimination of the therapeutic effect upon coadministration of a CD25 antibody (Figure 1H).

Glycopolymer-mediated therapeutic tolerance induction

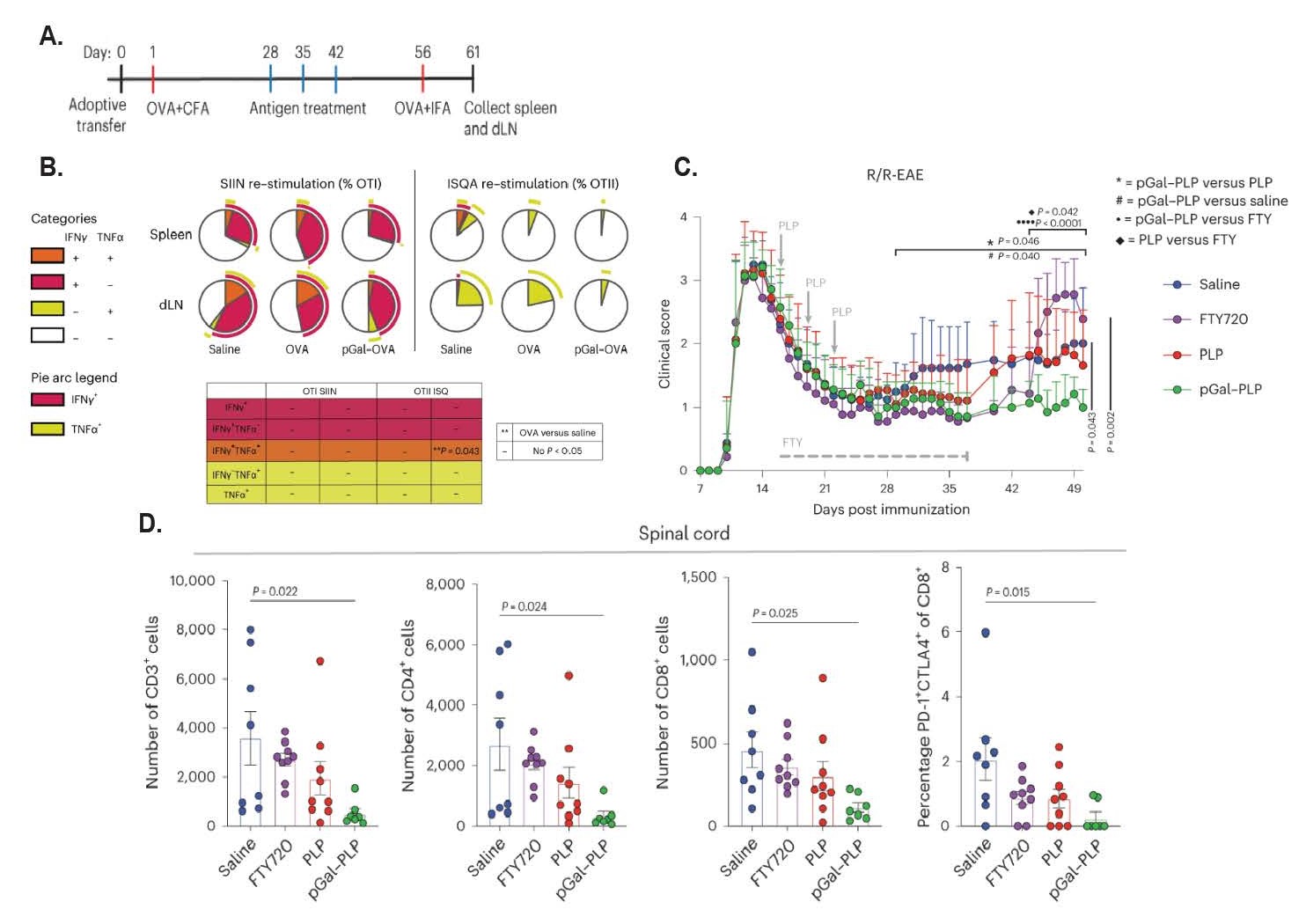

With the demonstration of these prophylactic effects of OVA-p(GalNAc) and OVA-p(GluNAc), the authors next wanted to prove the therapeutic effects of this glycopolymer-mediated antigen delivery in pre-sensitized animal models, which were examined in a 2023 publication by Tremain et al. [19]. After adoptively transferring OTI and OTII cells into C57BL/6 mice, a primary immunization of OVA emulsified in Complete Freund’s Adjuvant (CFA) was used to induce OVA sensitization. Starting four weeks later, mice were either vaccinated with three doses of saline, unmodified OVA, or OVA-p(GalNAc), before being rechallenged with an immunization of OVA emulsified in Incomplete Freund’s Adjuvant (IFA) (Figure 2A). In these rechallenged animals, OVA-p(GalNAc) treatment significantly reduced the recovery of OTI and OTII cell populations compared to saline and unmodified OVA. Moreover, these OTI and OTII populations were confirmed to be less pro-inflammatory than their non-glycopolymer-treated counterparts, as determined by their reduced capacity to produce interferon gamma (IFNγ) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) (Figure 2B). Similarly, these cell populations showed increased expression of immunosuppressive signals, including PD-1 in the OTI group, as well as anergic folate receptor 4 (FR4) and Treg upregulation in the OTII group. With this therapeutic effect proven, the authors next wanted to examine the impact of this glycopolymer treatment in a more clinically relevant setting: the experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) mouse model of multiple sclerosis (MS).

Figure 2: Therapeutic effects of glycopolymer-conjugated antigen delivery system in mouse models of OVA memory response and relapsing/remitting EAE. A. Dosing regimen for OVA-p(GalNAc) after establishment of OVA memory response via the use of CFA and IFA. One day after adoptively transferring ~75,000 OTI and OTII cells into wild type hosts, mice were sensitized to OVA via a subcutaneous administration of OVA/CFA. One month later, mice were treated with either OVA-p(GalNAc), OVA, or saline once a week for three weeks. An OVA/IFA secondary challenge was administered two weeks after the final dose. Spleens and lymph nodes were collected 5 days after secondary challenge. B. Ratio of OTI and OTII cells from spleen and lymph nodes based on secreted cytokines after restimulation with their target peptides, as quantified via intracellular flow cytometry. OVA-pGalNAc administration visibly lowered IFNγ production in splenic OTI cells, as well as reduced OTII TNFα production in both locations, though non-significantly. C. Dosing regimen for establishment of R/R-EAE model, overlaid with clinical scores over time after administration of saline, FTY720, PLP, or PLP-p(GalNAc). After induction of R/R-EAE on day 0 through an intraperitoneal injection of PTX, mice were administered saline, FTY720, PLP, or PLP-p(GalNAc) starting on day 16. While FTY720 was given orally on a daily basis for three weeks, saline and antigen-treated groups were given a total of three doses, which were each three days apart. PLP-p(GalNAc) successfully prevented rises in clinical score for the duration of the study. Statistical comparisons indicate differences in area-under-the-curve measurements as follows: *: PLP-p(GalNAc) vs PLP, #: PLP-p(GalNAc) vs saline, •: PLP-p(GalNAc) vs FTY720, ♦: PLP versus FTY720 D. Enumeration of spinal cord-infiltrating T-cells at experimental endpoint, as determined by flow cytometry. PLP-p(GalNAc) had fewer spinal infiltrates than other treatment groups. Statistical significance in B-D was calculated utilizing a Tukey’s multiple comparisons test after one-way ANOVA. Data is displayed as means ± S.E.M.

In a chronic EAE model, wherein mice develop an autoimmune response against myelin after receiving an adoptive transfer of splenocytes from a mouse that has been sensitized to myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG), the administration of MOG-p(GalNAc) 0, 3, and 6 days after the adoptive transfer was able to completely prevent the development of EAE. Similar effects of MOG-p(GalNAc) were observed when the glycopolymer was administered after disease onset; MOG-p(GalNAc)-treated mice demonstrated a significant reduction in disease scores and a near-baseline endpoint score compared to vehicle controls, as well as produced less inflammatory cytokines upon restimulation with MOG peptide. The authors next tested the potential of this glycopolymer strategy to prevent EAE relapse in a relapsing-remitting (R/R) model of MS that utilizes pertussis toxin-induced autoimmune responses against myelin proteolipid protein (PLP). Three doses of PLP-p(GalNAc) treatment were able to minimize disease clinical score and prevent EAE relapse in a comparable manner to fingolimod, a clinically relevant therapeutic used to prevent relapse in MS patients [31]. Notably, however, fingolimod could only prevent relapse for the duration it was provided, whereas PLP-p(GalNAc) suppressed disease for the entirety of the study (Figure 2C). PLP-p(GalNAc) treatment resulted in the lowest level of lymphocyte infiltration into the spinal cord compared to saline, fingolimod, or unmodified PLP (Figure 2D). However, overall lymphocyte numbers elsewhere in the body were unchanged, indicating autoantigen-specificity compared to the broad immunomodulation seen after fingolimod administration.

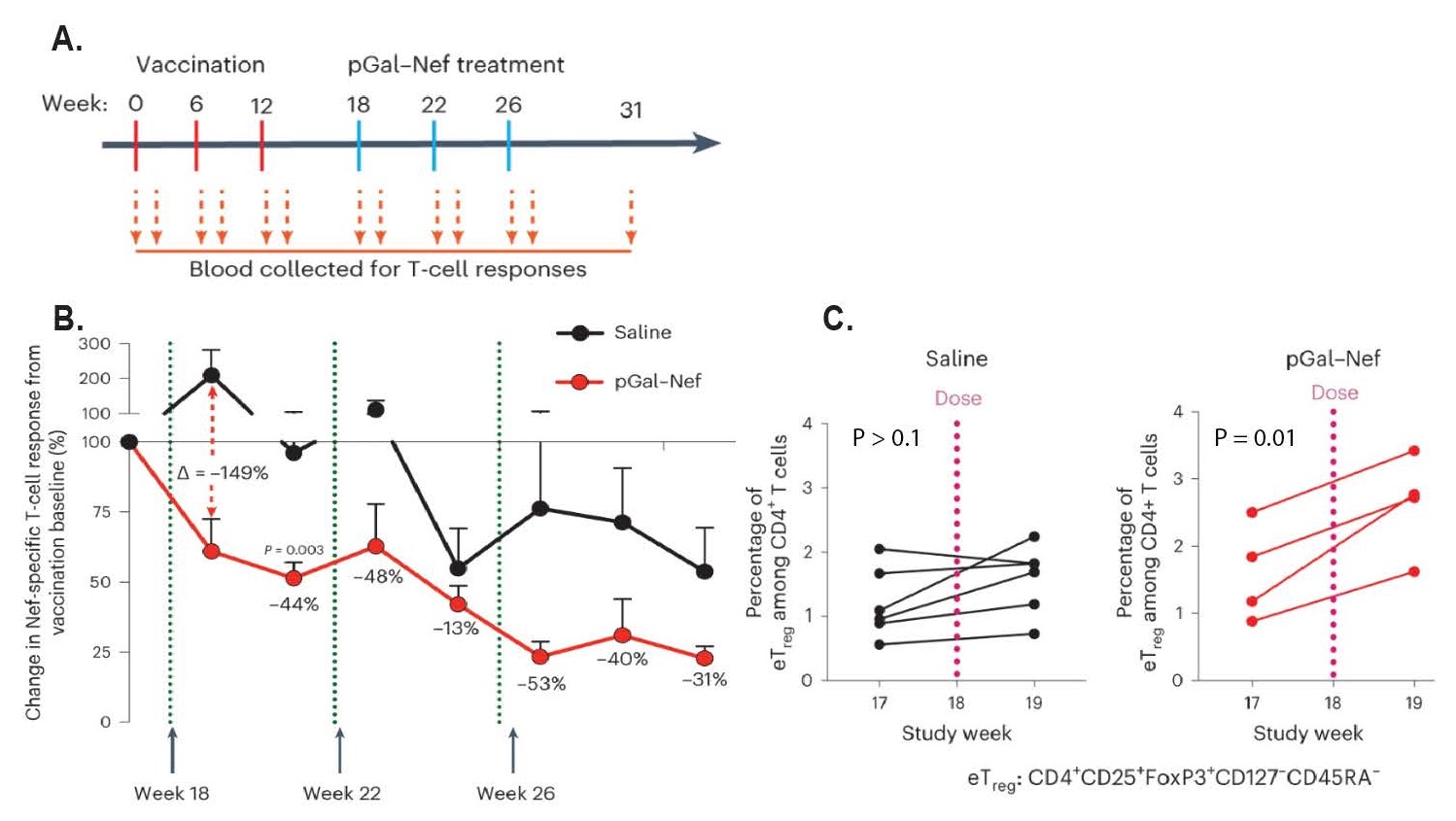

Lastly, the authors examined the translational capacity of p(GalNAc)-modified antigen by testing its ability to induce antigen-specific tolerance in nonhuman primates (NHPs). By injecting NHPs with a DNA-based simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) vaccine to various SIV proteins, including Nef, Gag, Env, and Pol, these NHPs develop a potent T cell response to SIV infection. After inducing this T cell response, the NHPs were administered IV infusions of saline or Nef-p(GalNAc) to induce antigen-specific tolerance against the Nef protein (Figure 3A). Indeed, Nef-p(GalNAc)-treated animals demonstrated both a significant loss of Nef-specific cellular immunity and an increase in Treg cell populations (Figures 3B and 3C). These results, along with no observed changes in other T cell populations nor decreased response to other, non-targeted antigens, demonstrate the ability of glycopolymer-mediated antigen delivery to induce tolerance in a highly selective, antigen-specific fashion.

Figure 3: Antigen-specific immunosuppression in nonhuman primate model of SIV after glycopolymer-conjugated antigen treatment. A. Dosing regimen for SIV vaccination and subsequent Nef-p(GalNAc) treatment. NHPs received a vaccination against SIV at week 0, 6, and 12, thereby inducing potent anti-SIV T-cell responses. At weeks 18, 22, and 26, animals were treated with either phosphate-buffered saline or Nef-p(GalNAc) to induce antigen-specific tolerance against Nef, a major SIV protein. B. Changes in Nef-specific T-cell responses after treatment administration in comparison to post-vaccination baseline, as indicated by IFNγ ELISPOT assays conducted on harvested PBMCs. A major reduction in IFNγ is observed between Nef-p(GalNAc) and saline-treated PBMCs. Data is displayed as means ± S.E.M. C. Frequency of Treg cells in each treatment group before and after antigen administration, in terms of the percentage of CD4+ T-cells. Nef-p(GalNAc) increases Treg frequency in comparison to saline. Statistical significance in B was determined via a Mann-Whitney test, while a two-tailed paired t-test was utilized to determine significance in C.

Future Directions

Glycopolymer-mediated antigen delivery to the liver serves as a novel, safe, and flexible platform for inducing antigen-specific tolerance with considerable therapeutic potential—via both the p(GalNAc) and p(GluNAc) constructs that served as the focus of this review, as well as derivatives of this technology that use mannose [20]. For example, prophylactic studies conducted by Wallace et al. and Cao et al. have demonstrated the potential to reduce anti-drug antibody responses and prevent the development of food allergies, respectively [20,32]. Based on these findings, diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus, celiac disease, and rheumatoid arthritis remain especially promising targets for this platform due to the liver’s inherent capacity to induce the aforementioned antigen-specific tolerogenic microenvironment.

Despite this positive outlook, some challenges remain. While Tremain et al. have demonstrated significant increases in effector Treg populations for up to six months after Nef-p(GalNAc) administration in nonhuman primates, the long-term durability of this antigen-specific tolerance remains undefined. Thus, future studies to examine the longevity of the tolerance induced by this technology are merited. Additionally, translation of future derivatives of this platform from animal models to humans may prove challenging due to species-specific differences in glycosylation receptors—like CD23, for instance, which is not conserved between mice and humans and recognizes different ligands between species [33]. This discrepancy accentuates the importance of identifying specific glycosylation patterns and receptors that can be universally targeted across species. Another limitation of this strategy is due to the patient-specific nature of many autoantigens. Since it is frequently impossible to know the antigen specificity of the autoreactive T cells which are causing the disease state in a particular patient with autoimmunity, it is often difficult to identify a universally applicable autoantigen for inclusion in the platform that will benefit every patient equally. That said, there are many techniques under development to identify patient-specific epitopes to address this limitation, including synthetic cellular circuits [34], labeled recombinant peptide-MHC multimers [35], and micropipette-based adhesion assays with two-dimensional tetramers [35].

Despite current limitations, liver-targeting glycopolymer-based strategies have demonstrated both safety and the capacity for translation to humans in their current forms, as exhibited by the successful completion of a Phase 1 clinical trial [36]. In terms of future directions, additional apoptotic and tolerogenic pathways in liver-resident cells offer further opportunities for manipulating antigen-specific tolerance. In addition to the C-type lectin receptors targeted by Wilson et al. and Tremain et al., Kupffer cells in the liver have the prominent ability to uptake and clear apoptotic cellular debris through a variety of other tolerogenic pathways, such as scavenger receptors, CD14, or macrosialin [37]. The existence and density of these receptors in the livers of individual patients could be determined by glycobiological spatial transcriptomics [38] or a graph-based domain adaptation model such as SpaRx [39], opening the door to patient-tailored targeting of autoantigens for more efficacious translation. All in all, while challenges such as verifying long-term tolerance and cross-species applicability remain, the plug-and-play nature of the chemistry used to tether specific antigens to the glycopolymer permits the conjugation of antigens with an available amine group. This broad utility, paired with the liver’s innate ability to tolerize both naïve and activated T cells, and the capability of induced pTreg cells to maintain durable antigen-specific tolerance, illustrates the increasing importance of this glycopolymeric technology.

Author Contributions Statement

I.M. performed literature search and wrote manuscript. S.L. and D.S.W. verified content and contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

D.S.W. is the holder of multiple patents associated with both the p(GluNAc) and p(GalNAc) glycopolymer delivery platforms and is a stockholder in Anokion SA—a company that utilizes glycopolymer-based strategies to induce immunological tolerance. I.C.M. and S.L. declare no competing interests.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (Award numbers: R21DA054740, DP2AI164306, R21EB031347) and the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (Grant No. XXXX). S.L. was also supported by the National Institutes of Health (Grants R01AI27644 and R01AI170709) and the Johns Hopkins Catalyst Award.

References

2. Martinez RJ, Andargachew R, Martinez HA, Evavold BD. Low-affinity CD4+ T cells are major responders in the primary immune response. Nat Commun. 2016 Dec 15;7:13848.

3. Corthay A. How do regulatory T cells work? Scand J Immunol. 2009 Oct;70(4):326-36.

4. Yadav M, Stephan S, Bluestone JA. Peripherally induced tregs - role in immune homeostasis and autoimmunity. Front Immunol. 2013 Aug 7;4:232.

5. Bachmann MF, Oxenius A. Interleukin 2: from immunostimulation to immunoregulation and back again. EMBO Rep. 2007 Dec;8(12):1142-8.

6. Borna S, Meffre E, Bacchetta R. FOXP3 deficiency, from the mechanisms of the disease to curative strategies. Immunol Rev. 2024 Mar;322(1):244-58.

7. Lim SP, Costantini B, Mian SA, Perez Abellan P, Gandhi S, Martinez Llordella M, et al. Treg sensitivity to FasL and relative IL-2 deprivation drive idiopathic aplastic anemia immune dysfunction. Blood. 2020 Aug 13;136(7):885-97.

8. Labrosse R, Haddad E. Immunodeficiency secondary to biologics. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2023 Mar;151(3):686-90.

9. Faustini F, Sippl N, Stalesen R, Chemin K, Dunn N, Fogdell-Hahn A, et al. Rituximab in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Transient Effects on Autoimmunity Associated Lymphocyte Phenotypes and Implications for Immunogenicity. Front Immunol. 2022 Apr 8;13:826152.

10. Guo Y, Lu N, Bai A. Clinical use and mechanisms of infliximab treatment on inflammatory bowel disease: a recent update. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:581631.

11. Wu S, Wang Y, Zhang J, Han B, Wang B, Gao W, et al. Efficacy and safety of rituximab for systemic lupus erythematosus treatment: a meta-analysis. Afr Health Sci. 2020 Jun;20(2):871-84.

12. Abraham AR, Maghsoudlou P, Copland DA, Nicholson LB, Dick AD. CAR-Treg cell therapies and their future potential in treating ocular autoimmune conditions. Front Ophthalmol (Lausanne). 2023 Apr 18;3:1184937.

13. Jansen MAA, Spiering R, Ludwig IS, van Eden W, Hilkens CMU, Broere F. Matured Tolerogenic Dendritic Cells Effectively Inhibit Autoantigen Specific CD4+ T Cells in a Murine Arthritis Model. Front Immunol. 2019 Aug 28;10:2068.

14. Sarkar D, Biswas M, Liao G, Seay HR, Perrin GQ, Markusic DM, et al. Ex Vivo Expanded Autologous Polyclonal Regulatory T Cells Suppress Inhibitor Formation in Hemophilia. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2014 Jul 30;1:14030.

15. Cliff ERS, Kelkar AH, Russler-Germain DA, Tessema FA, Raymakers AJN, Feldman WB, et al. High Cost of Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cells: Challenges and Solutions. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2023 Jun;43:e397912.

16. Sterner RC, Sterner RM. CAR-T cell therapy: current limitations and potential strategies. Blood Cancer J. 2021 Apr 6;11(4):69.

17. Saunders MN, Rad LM, Williams LA, Landers JJ, Urie RR, Hocevar SE, et al. Allergen-Encapsulating Nanoparticles Reprogram Pathogenic Allergen-Specific Th2 Cells to Suppress Food Allergy. Adv Healthc Mater. 2024 May 1:e2400237.

18. Kontos S, Kourtis IC, Dane KY, Hubbell JA. Engineering antigens for in situ erythrocyte binding induces T-cell deletion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013 Jan 2;110(1):E60-8.

19. Tremain AC, Wallace RP, Lorentz KM, Thornley TB, Antane JT, Raczy MR, et al. Synthetically glycosylated antigens for the antigen-specific suppression of established immune responses. Nat Biomed Eng. 2023 Sep;7(9):1142-55.

20. Wallace RP, Refvik KC, Antane JT, Brunggel K, Tremain AC, Raczy MR, et al. Synthetically mannosylated antigens induce antigen-specific humoral tolerance and reduce anti-drug antibody responses to immunogenic biologics. Cell Rep Med. 2024 Jan 16;5(1):101345.

21. Wilson DS, Damo M, Hirosue S, Raczy MM, Brunggel K, Diaceri G, et al. Synthetically glycosylated antigens induce antigen-specific tolerance and prevent the onset of diabetes. Nat Biomed Eng. 2019 Oct;3(10):817-29.

22. Rui L. Energy metabolism in the liver. Compr Physiol. 2014 Jan;4(1):177-97.

23. Zheng M, Tian Z. Liver-Mediated Adaptive Immune Tolerance. Front Immunol. 2019 Nov 5;10:2525.

24. Grakoui A, Crispe IN. Presentation of hepatocellular antigens. Cell Mol Immunol. 2016 May;13(3):293-300.

25. Akdis CA, Blaser K. Mechanisms of interleukin-10-mediated immune suppression. Immunology. 2001 Jun;103(2):131-6.

26. Shi Y, Massague J. Mechanisms of TGF-beta signaling from cell membrane to the nucleus. Cell. 2003 Jun 13;113(6):685-700.

27. Park IK, Shultz LD, Letterio JJ, Gorham JD. TGF-beta1 inhibits T-bet induction by IFN-gamma in murine CD4+ T cells through the protein tyrosine phosphatase Src homology region 2 domain-containing phosphatase-1. J Immunol. 2005 Nov 1;175(9):5666-74.

28. Tordesillas L, Berin MC. Mechanisms of Oral Tolerance. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2018 Oct;55(2):107-17.

29. Drouin M, Saenz J, Chiffoleau E. C-Type Lectin-Like Receptors: Head or Tail in Cell Death Immunity. Front Immunol. 2020 Feb 18;11:251.

30. Kolatkar AR, Leung AK, Isecke R, Brossmer R, Drickamer K, Weis WI. Mechanism of N-acetylgalactosamine binding to a C-type animal lectin carbohydrate-recognition domain. J Biol Chem. 1998 Jul 31;273(31):19502-8.

31. Chun J, Hartung HP. Mechanism of action of oral fingolimod (FTY720) in multiple sclerosis. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2010 Mar-Apr;33(2):91-101.

32. Cao S, Maulloo CD, Raczy MM, Sabados M, Slezak AJ, Nguyen M, et al. Glycosylation-modified antigens as a tolerance-inducing vaccine platform prevent anaphylaxis in a pre-clinical model of food allergy. Cell Rep Med. 2024 Jan 16;5(1):101346.

33. Jegouzo SAF, Feinberg H, Morrison AG, Holder A, May A, Huang Z, et al. CD23 is a glycan-binding receptor in some mammalian species. J Biol Chem. 2019 Oct 11;294(41):14845-59.

34. Kohlgruber AC, Dezfulian MH, Sie BM, Wang CI, Kula T, Laserson U, et al. High-throughput discovery of MHC class I- and II-restricted T cell epitopes using synthetic cellular circuits. Nat Biotechnol. 2024 Jul 2.

35. Rojas M, Acosta-Ampudia Y, Heuer LS, Zang W, M Monsalve D, Ramirez-Santana C, et al. Antigen-specific T cells and autoimmunity. J Autoimmun. 2024 Sep; 148:103303.

36. Murray JA, Wassaf D, Dunn K, Arora S, Winkle P, Stacey H, et al. Safety and tolerability of KAN-101, a liver-targeted immune tolerance therapy, in patients with coeliac disease (ACeD): a phase 1 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Aug;8(8):735-47.

37. Blondet NM, Messner DJ, Kowdley KV, Murray KF. Mechanisms of hepatocyte detoxification. In: Said HM, Editor. Physiology of the Gastrointestinal Tract. 6th Edition. Academic Press; 2018 Jan 1. pp. 981-1001.

38. Dworkin LA, Clausen H, Joshi HJ. Applying transcriptomics to studyglycosylation at the cell type level. iScience. 2022 May 18;25(6):104419.

39. Tang Z, Liu X, Li Z, Zhang T, Yang B, Su J, et al. SpaRx: elucidate single-cell spatial heterogeneity of drug responses for personalized treatment. Brief Bioinform. 2023 Sep 22;24(6):bbad338.