Commentary

In their recent article, “Jail-Based Competency Treatment Comes of Age,” Jennings et al. [1] reviewed the historical development of the model and presented the first largescale empirical support for its effectiveness, which covered eight years of outcomes across four different program sites for nearly 2,000 Incompetent to Stand Trial (IST) defendants. As expressed in the title of the article, they asserted that the jail-based competency treatment (JBCT) model is, for better or worse, here to stay. For mental health advocates and other critics of the concept of jail-based restoration, the establishment of jail-based competency treatment may be an unwelcome development. This commentary looks at the emergence of the JBCT from a broader “30,000 foot” perspective that puts JBCT in the context of how JBCT can best be applied within the current realities of the forensic mental health crisis in America.

The “Competency Services Crisis” and its Causes

In 2017, the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors [2] reported a 25% increase in the number of IST patients receiving competency restoration services between 1999 and 2005, and a 37% percent increase between 2005 and 2014. Similarly, Warburton et al. [3] surveyed the jurisdictions of all 50 states and DC and found that 82% and 78% reported an increase in referrals for competency evaluations and competency restoration treatment respectively.

Gowensmith [4] coined the term “competency services crisis” to describe this continuing and unprecedented escalation in the demand for competency restoration and related forensic services in recent years. Similarly, Callahan and Pinals [5] concurred that the nation’s IST system “is in crisis” and called for “empirical research on the individual- and system-level factors that contribute to the waitlists and system paralysis.”

In California, in particular, the ever-rising demand for IST services has been unrelenting despite the large-scale adoption of the JBCT model and diligent efforts to reduce statewide waiting lists for competency treatment. From a starting point of one 20-bed JBCT pilot unit in 2011, the state has expanded the model to about 15 county-based JBCT units with over 425 beds of total capacity. Nevertheless, capacity continues to be outpaced by the demand for competency restoration.

Paradoxically, it may be that the benefits of using JBCT to accelerate and facilitate improved access to restoration services may be (positively) contributing to the rising demand for IST services in California. JBCT has never been intended to replace traditional inpatient hospital treatment [6], and it is clearly not a singular answer to the complexities of the national and worsening IST crisis.

Looking at the Causes

By looking at the causes of the competency services crisis from 30,000 feet, we may develop a clearer understanding and perspective on a solution. When asked to rank-order the leading causes of the competency crisis in their respective 51 jurisdictions, the state respondents opined that the foremost cause is basic inadequacies in general community-based mental health services, followed by inadequacies in crisis services, community-based inpatient beds, and assertive community treatment services [3].

In 2019, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) issued their own view of the causal origins, historical development, and current status of involuntary commitment in the United States. The SAMHSA review revisited the deinstitutionalization movement that relocated tens of thousands of long-term psychiatric patients into community settings. Driven by optimism about more effective antipsychotic medications and treatments, and belief in the anticipated positive effects of normalized living in the community, policy makers put their faith in the establishment of a strong community-based mental health system.

But the medicines alone were never quite as effective as promised… and the comprehensive community-based care system that was envisioned to meet the complex needs of persons with severe, disabling disorders such as schizophrenia never fully materialized [7].

Ultimately, the failure to invest fully in strong communitybased mental health services resulted in generations of adults with serious mental illnesses who could not afford, access, or benefit from consistent psychiatric treatment. All too often, these individuals would drop out of reliable treatment, become homeless and jobless, misuse drugs and alcohol, or otherwise succumb to a cycle of clinical deterioration and “revolving door” hospital admissions for acute short-term care.

At the same time, large numbers of these individuals would become involved with the criminal justice system because of offenses and behavior resulting from impaired judgement and other untreated psychiatric symptoms. By the early 1970s, it was evident that the emptying of the state mental hospitals was fueling dramatic increases in the number of mentally ill individuals in jails and prisons. Moreover, as the pace of deinstitutionalization accelerated in the 1980s and early 1990s, the numbers and percentage of mentally ill individuals in jails and prisons continued to escalate. In 2010, Torrey et al. [8] affirmed that three times more mentally ill persons are in jails and prisons than hospitals. Today, jail and prisons have become the de facto mental health providers for masses of people with mental illness in America [9]. With weak hopes that adequate funding and resources will be directed to the original dream of a strong community mental health system, advocates like the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) have needed to shift their efforts to improving access to mental health care within prison and jail settings [10,11].

Implementation of JBCT as a Response to the “Competency Services Crisis”

An appreciation of these broader historical trends is important for understanding the origins and expansion of the jail-based competency treatment model. First, the continuing underfunding of community mental health service systems means that the core problems will continue to drive people with severe mental illness into the criminal justice system. Second, to the degree that jail- and prison-based mental health care has become the accepted norm in the USA, the concept of jail-based restoration of competency treatment has also become more acceptable.

Third, in the absence of viable mental health diversion options, the best legal strategy for protecting the safety and welfare of a homeless or despondent defendant in acute mental health crisis may be to pursue the avenue of civil commitment via Incompetency to Stand Trial – especially if the person is charged with a felony and presents a risk to the community. Thus, a court order for restoration of competency treatment can safely get the vulnerable individual “off the street” and obtain the psychiatric medication and treatment that is so desperately needed – even if such medication or treatment is against their current (presumably judgementimpaired) will, and even if they need to “wait” in a jail setting for admission to the state hospital (or a JBCT unit or some other diversion program) in order to get that treatment.

Judges and lawyers have taken to using the “incompetence” label as a way to get people with serious mental illness and forensic involvement into treatment because of their belief – and to some extent the reality – that placing those individuals in psychiatric hospitals is the only way to get them mental health care.” [12].

The problem with this strategy, however, is that the “care” is focused mainly, if not exclusively, on the restoration of competency. The explicit goal of competency treatment is to help the individual to gain the “legal” skills and knowledge they need to understand the proceedings against them and participate in their own defense. But they are not getting the kind of treatment that will improve their long-term recovery, such as substance use or trauma treatment or interventions that can address homelessness and vocational autonomy. This is the reason that many restoration of competency treatment models take a primarily educational approach that delivers a generic, “one-size-fits-all” classroom-like curriculum of topics (e.g., roles of courtroom personnel, types of pleas, adversarial nature of trial process, evaluating evidence, court room behavior, sentencing, etc.).

In contrast to this educational approach with its narrow focus on legal concepts and courtroom protocol, the Liberty “ROC” (restoration of competency) model emphasizes treatment that applies medication and individualized use of multi-modal interventions that can first resolve the psychotic symptoms and thereby enable the patient to regain his general thinking capabilities [1,6,13]. In this model, the primary impediment to restoration of competency is usually the patient’s psychosis, not his lack of understanding of legal concepts. The problem with the educational approach is that the program applies the same classes for every patient without an appreciation for the individual’s level of functioning or need for such instruction. Many have low IQ and cognitive deficits and are completely overwhelmed by too much information.

There is also questionable value in trying to deliver didactic instruction and role-play to psychotic patients who may be dozing or delusional or hallucinating or otherwise unable to attend to the information. Therefore, in the Liberty ROC model, the primary goal in competency restoration is to resolve the psychosis, improve cognitive functioning, and foster motivation – and thereby enable the patient to regain his general thinking abilities and functioning.

Still, even the more holistic and individualized approach of the Liberty ROC model is necessarily limited by the legal mandate for restoration of competency that restricts treatment to one short-term goal: restoration of competency. Treatment of other needs and issues that could promote long-term recovery is not the purpose and is, in a sense, not allowed. For example, the treatment program can detox and help an individual “get clean” from a substance use disorder as part of psychiatric stabilization, but there is little time or resources available to help the individual gain the skills for long-term abstinence and recovery.

Definition of JBCT

Although there are variations across states and jurisdictions, we offer the following simplified description of the “jail-based competency treatment” process. The typical scenario begins when an individual with a severe mental illness is arrested for a criminal offense. The individual is then held in a local jail or detention center until the court can adjudicate the offense charge or there is a motion for a pre-trial competency hearing. The defense or prosecuting attorney or both may question the defendant’s mental competency out of concern for the person’s welfare and/or for strategic legal reasons. The defendant is then formally evaluated by a court-assigned psychiatrist (“alienist”), psychologist, or other qualified clinician (often by two such clinicians) to determine whether the individual is Incompetent to Stand Trial (“IST”), Incapacity to Proceed (“ITP”), or similar terminology. If deemed incompetent, defendants are then held in the jail or detention center until they can be transferred to the state forensic hospital for the court-ordered treatment to restore competency. Typically, those charged with felony offenses are regarded as too dangerous or vulnerable to be released or diverted to the community (but misdemeanors might also apply in some jurisdictions).

The problem with the traditional standard of inpatient state hospital treatment for IST defendants is that nearly everystate mental health system has a severe shortage of forensic psychiatric inpatient beds. Consequently, defendants are very often placed on a “waiting list” and may be detained in the local jail for an indefinite period of time until they can be admitted. The sad reality is that IST patients with severe mental illness can often languish in jail for months and months without “access to meaningful psychiatric care and not moving forward in the legal process as they await admission to grossly undersized and understaffed state hospitals... The combination of inadequate psychiatric care, the stress of incarceration, and the long waits involved have yielded nightmarish results” [14].

In short, despite the obvious fact that correctional facilities are not designed for psychiatric care and often lack mental health staff, program space, and treatment capacity, local jails are burdened with the primary responsibility for caring for defendants with severe mental illness during the indefinite and typically extended period of “waiting” for admission to the court-ordered competency treatment. Thus, the foremost humanitarian purpose of JBCT is to reduce the length of time that individuals with severe mental illness spend “waiting” in local jails by accelerating the initiation of mental health services and competency-targeted treatment. For the jailbased concept to be feasible, however, someone needed to first demonstrate that a jail unit could be transformed - through staffing, environmental modifications, and behavioral management – into a safe and reasonably therapeutic milieu for acute psychiatric stabilization and restoration of competency treatment. Implemented and operated by a private behavioral health provider in Virginia from 1997 to 2003, the “Liberty Forensic Unit” succeeded in showing the restoration of competency (“ROC”) treatment model could be effective [13]. In 2009, the same company proposed the ROC model to the California Department of State Hospitals as a solution to its waiting list crisis and opened the first 20-bed ROC unit in San Bernardino County in 2011 [6]. Key components of the model include the following:

- Establishing a designated housing and treatment unit that separates IST patients from all other inmates.

- Establishing an interdisciplinary team of psychiatrists, psychologists, nurses, and other mental health clinicians, including participation from designated custody staff with mental health training.

- Completing a comprehensive interdisciplinary assessment of psychological functioning, suicide and behavior risk, current level of trial competency, and possible malingering, often using a battery of psychological tests.

- Continuing assessment and treatment that is specifically focused upon (or limited to) addressing needs and issues currently related to restoration of competency to stand trial (as distinguished from addressing overall psychological problems).

- Keeping treatment and determination of restorability within a specified short-term period of about 60-80 days (thus conserving long-term treatment as appropriate for the state hospital).

- Providing an array of individual and group-based treatment modalities, including competency-specific education, counseling, and psychoeducational sessions.

For definitional purposes, Wik [15] distinguishes two types of JBCT: “Full scale” JBCT programs typically dedicate a unit or pod within a jail for a day-treatment-like program of individual and group-based therapeutic and competency focused activities, while serving as a housing unit for IST patients. “Time-limited” JBCT services are typically limited to competency tutoring that are provided to individuals while they are awaiting admission to the state hospital (called “stop-gap” services by Gowensmith, et al. [16]).

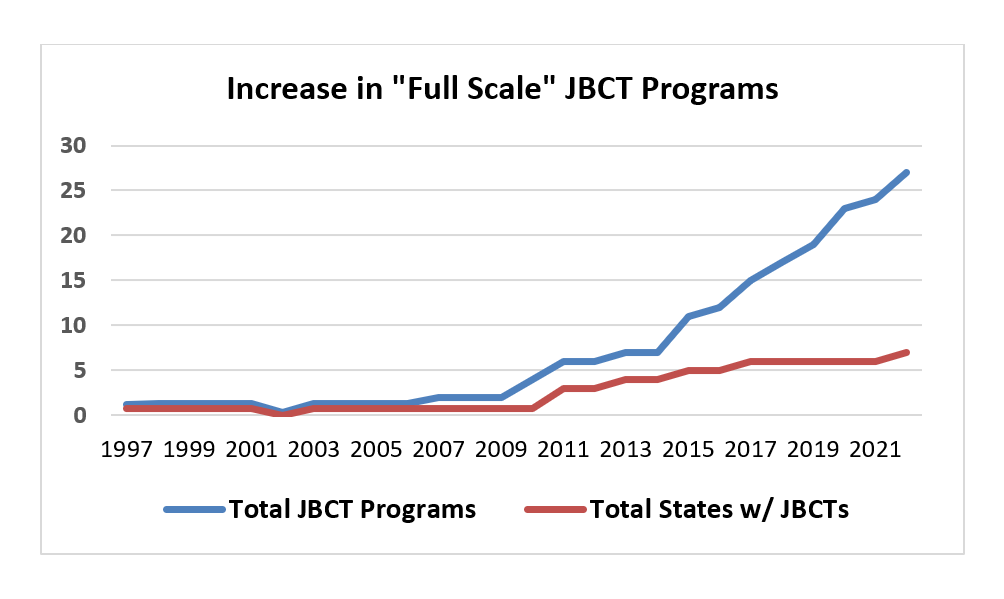

Figure 1 shows the historical growth of the JBCT model in terms of the estimated total number of full scale programs and number of states with full scale programs.

Figure 1. Historical growth of the JBCT model.

Challenges to the Fidelity of the JBCT Model

Granted that the JBCT model is now established and growing, it is important that attention is given to the fidelity of the JBCT model, which should guide its future growth. As noted above, however, there has been tremendous variability in its application. One of the tenets of implementation science is fidelity of the model [17]. Fidelity is the most often-measured implementation outcome and is defined as “the degree to which an intervention was implemented as it was prescribed in the original protocol” in terms of adherence, dose or amount of program delivered, and quality of program delivery. As observed by Jennings et al. [1], there is no clear “original protocol” for JBCT, and its historical development is an example of what not to do in terms of the following ideals of implementation science: The research evidence should be strong before implementation is justified. It was not. There should be careful planning and “deliberate and purposive actions” to implement a new treatment [17]. On the contrary, implementation of JBCT has been unsystematic and disorganized at best. The criteria for evaluating the model’s effectiveness should be agreed upon before implementation. The only prior agreement regarding JBCT has been a shared pursuit of a solution to the national “competency crisis.”

Even if the “original protocol” of the JBCT model is restricted to “full scale” jail-based units that house IST patients together, programs differ in terms of their size/capacity, eligibility criteria, staffing mix, capacity to use involuntary medication, program components, separation of competency evaluators and competency treaters, and other parameters. The recent study by Jennings et al. [1], was a strong attempt to control much of the above variation by applying the same specified JBCT methodology at four different “full scale” program sites. Yet, even with this research study of four seemingly equivalent treatment sites, the authors discovered a critical difference in outcomes arising from an unrecognized difference in administrative protocol.

Specifically, they discovered that IST patients, who were treated in an “out-of-county” JBCT, had a significantly shorter average length of restorative treatment (35.4 days) compared to those from nearby Los Angeles County (41.0 days) and those treated in an in-county JBCT in their home county (58.4 days). Upon closer examination, the critical factor was an administrative procedural difference that delayed the time that out-of-county patients are admitted to the JBCT to begin restoration. This unaccounted “pre-admission time” spent in jail before admission to the JBCT unit was a critical time period during which individuals could detoxify from substances and, depending on the resources of the originating jail, receive some psychiatric medications and treatment to begin stabilizing their conditions, or even experience some degree of “spontaneous recovery.” In short, the out-of-county IST patients from Los Angeles County and all other referring California Counties were less acutely disturbed at the time of admission than those fast-tracked into their home County JBCT.

This study reflects the tremendous complexity of factors at play in conducting treatment outcome research in real world forensic settings. Most importantly, it yields an essential lesson for future research on JBCT. In order to make fair comparisonsbetween JBCT programs and between jail- and hospital- based restoration, future research needs to carefully define and control for the influence of pretreatment “administrative” differences by tracking three crucial dates: the date of arrest, the date of court-ordered referral, and the date of actual admission. In real world terms, the variations in waiting time and the impact of mental health treatment services received prior to admission to JBCT may be the area of greatest difference among JBCT programs nationally.

These complexities and variations in methodology are, of course, not unique to JBCT. There is no less variation across hospital-based programs nationally on many of the same variables that critics express concern about in JBCT. One could argue that the whole field of competency restoration treatment lacks clear evidence-based interventions. To quote from the “attempted meta-analysis” by Pirelli and Zapf [18], “virtually no published data reflect specific intervention efforts that lead to competence restoration.” They also observed that “competency restoration procedures were overwhelmingly nonspecific across studies and not reported in more than half of them.”

Conclusion: The Need for a Continuum of Options

In closing, we have seen that the rise of the JBCT model has been fueled by the “Competency Services Crisis,” which is itself rooted in the fundamental inadequacies of the community mental health services system and the national shortage of state hospital forensic beds. JBCT should never be regarded as a replacement for inpatient forensic psychiatric treatment. Rather, JBCT should be just one choice in a continuum of competency restoration service options that enables the IST system to match the individual’s restoration needs to the type and intensity of restoration services needed.

In an ideal world, state and county systems should have a continuum that includes less intensive and/or alternative methods of competency restoration, such as outpatient restoration, restoration provided to ISTs in general population in jails, pre-trial diversion services for mental health and substance use, use of the Sequential Intercept Model [19] for diversion, and jail-based competency treatment (JBCT) units. The “JBRU” program provided in metropolitan Atlanta presents a real-world example of a successful continuum [20]. Depending on the individual’s needs, IST patients can be referred to any of six options: outpatient restoration at a local public psychiatric hospital; individual competency tutoring while housed in the general jail population; diversion out of corrections for mental health services; “specialized day-treatment” in a designated 16-bed JBCT unit; a special program for women; and inpatient hospitalization.

Two more promising interventions in the continuum of restoration options are “off-ramping” and “Early Access and Stabilization Services (EASS),” which are being piloted by the California Department of State Hospitals in 2022. The EASS (as in “ease”) model calls for forensic professionals to go into the county jails to meet with individuals who are “on the waiting list” for admission to the state hospital or an JBCT program in order to start appropriate medications as early as possible for stabilization of acute psychiatric illness. IST patients are seen weekly by a psychiatrist or nurse practitioner, while clinicians and competency teachers focus on individual restoration issues two to three times a week. The “off-ramping” model focuses more on individuals who have been waiting for longer periods of time and identifies and assesses those whose condition has improved to a point of competency and no longer require admission to intensive JBCT or inpatient hospital treatment.

Viewed from 30,000 feet, there is little reason to expect any major improvements in the development of well-funded and effective community mental health service systems, so the rising demand for IST treatment will continue. In this context, our best current hope is to build programs to divert more individuals with serious mental illness to community-based treatment and improve the continuum of forensic options, in which JBCT can play a leading role.

References

2. National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors (2017). Forensic Patients in State Psychiatric Hospitals: 1999-2016. Brief found at: https://www.nri-inc.org/media/1318/tac-paper-9- forensic-patients-in-state-hospitals-final-09-05-2017.pdf

3. Warburton K, McDermott BE, Gale A, Stahl SM. A survey of national trends in psychiatric patients found incompetent to stand trial: Reasons for the reinstitutionalization of people with serious mental illness in the United States. CNS Spectrums. 2020 Apr;25(2):245-51.

4. Gowensmith WN. Resolution or resignation: The role of forensic mental health professionals amidst the competency services crisis. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law. 2019 Feb;25(1):1.

5. Callahan L, Pinals DA. Challenges to reforming the competence to stand trial and competence restoration system. Psychiatric Services. 2020 Jul 1;71(7):691-7

6. Rice K, Jennings JL. The ROC program: Accelerated restoration of competency in a jail setting. Journal of Correctional Health Care. 2014 Jan 1;20(1):59-69

7. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Civil Commitment and the Mental Health Care Continuum: historical trends and principles for law and practice. https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/civil-commitment-continuum-of-care.pdf

8. Torrey EF, Kennard AD, Eslinger D, Lamb R, Pavle J. More mentally ill persons are in jails and prisons than hospitals: A survey of the states. Arlington, VA: Treatment Advocacy Center. 2010 May:1-8.

9. Roth A. Insane: America’s criminal treatment of mental illness. Basic Books. 2018.

10. National Alliance on Mental Illness (2020). “Divert to What? Community Services that Enhance Diversion.” NAMI publication. Downloaded from: https://www.nami.org/Support-Education/ Publications-Reports/Public-Policy-Reports/Divert-to-WhatCommunity-Services-that-Enhance-Diversion/DiverttoWhat.pdf

11. National Alliance on Mental Illness (2022). “Mental Health Treatment While Incarcerated. Where We Stand”. Downloaded from: https://www.nami.org/Advocacy/Policy-Priorities/ImprovingHealth/Mental-Health-Treatment-While-Incarcerated

12. Deangelis T. Standing tall: A new stage for incompetency cases. APA Monitor on Psychology. 2022 Jun:56-65.

13. Jennings JL, Bell JD. The “ROC” model: Psychiatric evaluation, stabilization and restoration of competency in a jail setting. Mental illnesses: Evaluation, Treatments and Implications. 2012 Jan 13:75-88. Downloaded from: https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/25947

14. Wortzel H, Binswanger IA, Martinez R, Filley CM, Anderson CA. Crisis in the treatment of incompetence to proceed to trial: Harbinger of a systemic illness. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2007;35(3):357-63.

15. Wik A. Alternatives to inpatient competency restoration programs: Jail‐based competency restoration programs. Falls Church, VA: NRI Analytics Improving Mental Health. 2018.

16. Gowensmith WN, Murrie DC, Packer IK. Forensic mental health consultant review final report. Contract #1334-91698. 2014 Jun 30.

17. Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A et al. Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2011 Mar;38(2):65-76.

18. Pirelli G, Zapf PA. An attempted meta-analysis of the competency restoration research: Important findings for future directions. Journal of Forensic Psychology Research and Practice. 2020 Mar 14;20(2):134-62.

19. Pinals DA, Callahan L. Evaluation and restoration of competence to stand trial: intercepting the forensic system using the sequential intercept model. Psychiatric Services. 2020 Jul 1;71(7):698-705.

20. Ash P, Roberts VC, Egan GJ, Coffman KL, Schwenke TJ, Bailey K. A jail-based competency restoration unit as a component of a continuum of restoration services. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. 2020 Mar 1;48(1):43.