Abstract

Background: Adolescents with mental disorders often have difficulty engaging in ongoing treatment. Dropout from treatment is common.

Aim: This paper aims to explore the clinical characteristics of a cohort of adolescents with mental disorders who were stably and actively undergoing psychotherapy over a relatively long period of time (for at least four months).

Method: A purposive single-center cross-sectional cohort survey was conducted from June 2016 to December 2019. The sample of the study (N=50) was recruited from the Child and Adolescent Psychiatry outpatient setting of a large tertiary hospital of Thessaloniki, the second largest city in Greece. An intelligence test (Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, WISC III) and a self-report measure of depression (Beck Depression Inventory, BDI II) were used. All the participants underwent a rigorous clinical assessment of their mental health status in both initial and ongoing psychotherapy. The initial diagnosis was reconfirmed during the course of therapy. Mental disorders were defined and diagnosed using the ICD-10 (1992) (International Classification of Diseases).

Results: The largest percentage of adolescents (44.9%) were found to suffer from mood (affective) disorders, while 20.4% suffered from neurotic disorders. We also found high prevalence of pessimism (32.7%), reduction of energy (28.6%) and difficulty in concentration (32.7%). A total of 22.4% of adolescents reported sleep disorders. A limited interest in sex was noted, which was in contrast with international and Greek data, where interest and experimentation around sex seems to preoccupy a high percentage of adolescents. Furthermore, sleep disorders, either as a symptom of an underlying disease or as an independent clinical condition, seem to preoccupy adolescents, and this may be a motive for them to seek treatment.

Conclusion: For the most part, the findings of this study were consistent with the findings of prior studies; however, previous studies did not exclusively include adolescents engaging in ongoing psychotherapy. As we identified some inconsistencies with prior studies related to interest in sex and sleep disorders, further research is recommended for the investigation of possible correlations between these findings and ongoing psychotherapy engagement rates. Note, however, that the findings in this study are not representative of adolescents in Greece due to the fact that the used sample was not representative.

Keywords

Adolescent(s), Psychotherapy engagement, Mental disorders, Clinical characteristics

Introduction

Adolescence is defined as the transitional phase between ages 10 and 19 [1]. However, adolescence is a culturally defined concept without a clear-cut starting (and ending) point [2]. Approximately 20% of adolescents experience a mental health problem, the most common of which are depression and anxiety [3]. Mental health problems increased in adolescents and young adults in Europe between 1950 and 1990, and the cause is largely unknown [4]. The literature on the prevalence of mental disorders among children and adolescents in the general population has significantly increased in recent years [5,6]. Most mental disorders start during childhood, adolescence and early adulthood [7]. Rates of diagnoses have increased substantially [8]. Adolescent mental health problems are an increasingly concerning public health issue. Globally, mental (and substance use) disorders are the leading cause of disability in young people [9]. Laufer [10] states that it is difficult to define mental disorders in adolescence, and there is controversy regarding this topic.

The problem of attrition from mental health therapy (which reduces the success rate of psychotherapy) is pervasive throughout the mental health field and poses an important mental health risk for patients, therapists and the mental health care sector [11]. Several attempts have been made to explore the reasons for and the risk factors for psychotherapy attrition. Effective methods to engage clients in therapy are still under discussion. Creating an optimum collaborative working involvement between therapists and clients is crucial to achieve successful treatment engagement [12]. Treatment engagement is decisive in forming an effective therapeutic process and ‘may be particularly relevant early in treatment’ [13]. For instance, a strong therapeutic alliance and client satisfaction have a positive impact on dropout rates [14]. A meta-analysis conducted by Sharf, Primavera and Diener demonstrated “a moderately strong relationship between psychotherapy dropout and therapeutic alliance” in the context of adult individual psychotherapy [15]. Engaging clients in a discussion about the treatment option that best fits their values and preferences (“shared decision making”) may lead to greater treatment satisfaction and hence may be one of the practical tips for ensuring ongoing therapy engagement. Shared decision-making “is increasingly being suggested as an integral part of mental health provision” [16] and is particularly so in the context of child and adolescent psychiatry [17]. Shared decision making is at the core of the patient-centered care model in any area of medicine. Moreover, the use of a patient-centered care model in the mental health care context has promising outcomes for treatment engagement [18].

Importantly, it is widely accepted that a large subset of adolescents generally has the capacity to engage in decisions about their treatment and to consent to medical treatments in specific contexts [19]. However, little is known about the capacity of adolescents with psychiatric mental disorders to consent to treatment [20]. It is crucial to consider that persons with mental disorders do not necessarily lack decision-making competence [21-23]. Values, preferences, and emotions play an important role in the decision-making process [24]. However, it is impossible to define a cutoff point of consent for medical treatment based on neuroscience [25]. At any rate, adolescents should be involved in treatment decisions as much as possible [26,27]. Their involvement in medical decisions has proven beneficial to them [27,28].

Adolescents with mental disorders often have difficulty engaging in ongoing treatment. Dropout from treatment is common. It is arguably stated that “attrition in youth outpatient mental health clinics ranges from 30 to 70% and often occurs early in treatment” [13]. Engaging adolescents is especially challenging “because of their developmental immaturity, the stigma many adolescents associate with psychotherapy, and adolescents feeling forced into psychotherapy” [12]. Roos and Werbart found that in the context of adult individual psychotherapy dropout rates “varied widely with a weighted rate of 35%” [14].

In short, while a large subset of adolescents with mental disorders maintains their ability to be fully engaged in a shared clinical decision-making process, a large subset of adolescents with mental disorders cannot engage in ongoing psychotherapy. We hypothesized that certain clinical characteristics are common among adolescents with mental disorders who do not drop out of ongoing psychotherapy. In this perspective, we aimed to explore the distribution of characteristics of outpatient adolescents who engaged in ongoing psychotherapy in a Greek tertiary hospital from June 2016 to December 2019. The ultimate aim of this study was to inform the design of future studies regarding the possible relationship between these characteristics and ongoing psychotherapy engagement rates. Such a relationship (if any) might contribute to improving therapeutic effectiveness in the context of adolescent psychotherapy.

Research Question

The overarching research question that defined the focus of this study was as follows:

“What was the distribution of patient characteristics of a cohort consisting of outpatient adolescents with mental disorders who were able to keep themselves from dropping out from their ongoing psychotherapy engagement?”

Methods

Study design

A purposive single-center cross-sectional cohort survey was conducted. This study was part of a broader research project exploring the reasons for and risk factors for psychotherapy attrition among adolescents with mental health disorders.

Sampling

A purposive sampling was used to select quantitative research respondents. A face-to-face sample survey of 50 adolescents with mental disorders aged 13–18 years was conducted. A total of 50 adolescents (aged 13-18 years, mean=14.8, SDs= 1.616) with psychiatric disorders engaged in an outpatient mental health setting (Child and Adolescents Psychiatry department, tertiary hospital Hippokratio of Thessaloniki, the second largest city in Greece) participated in the study. As the tertiary hospital, Hippokratio is one of the largest hospitals in the Northern Greece, and anyone adolescent with a mental disorder living in the Northern Greece could be outpatient in the healthcare setting of the study. The study was conducted from July 2017 to December 2019.

All the participants had been undergoing mental health treatment (psychotherapy) for at least four months. The type of psychotherapy included in the sample was systemic psychotherapy. In the abovementioned child and adolescent mental health setting (where the author ET is working) psychotherapy sessions were taking place using a systemic approach. The primary therapist was the author ET. ET often had to deal with multiple alliances, including the parent-therapist alliance and adolescent-therapist alliance, which are key contributors to effective therapy. Bearing in mind adolescents’ high vulnerability to external influences, psychotherapy sessions were conducted focusing on addressing current relationship patterns and more precisely those regarding relationships between the adolescents and the characteristics of the social network positions within which they are embedded. Importantly, adolescent brains have plasticity that depends on physical and psychosocial experiences, which places them at risk for developing abnormal behaviour and mental disorders. Adolescents are vulnerable to experiences which can change the structure and function of their neural network, including altering the connection between neurons [29]. Furthermore, during the therapy the author ET and her co-workers were bearing in mind that client–therapist working alliance and therapist adherence interrelate (reinforce one another) over the course of the systemic psychotherapy, irrespective of client characteristics [30].

Sample size

Extreme (or deviant) case sampling was used. It is a type of purposive sampling. The sample members were selected based on characteristics of a population (outpatient adolescents with mental disorders) and the overall goal of the study. Appropriate adolescent patients were picked for inclusion in the sample. Data collection ceased when a number of selected useful cases (respondents) were reached, which allowed for a sound statistical analysis of the dataset. Finally, only 50 adolescents were included because of the very small number of new potential participants per month and difficulties in getting informed consent from parents and adolescents.

Measures

To ensure the diagnosis of participants’ mental health disorders, all the participants underwent a rigorous clinical assessment of their mental health status in both initial and ongoing psychotherapy engagement. In the initial phase of psychotherapy engagement, potential participants completed two psychometric scales: An intelligence test (Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, WISC III) and a self-report measure of depression (Beck Depression Inventory, BDI II).

Cut-off values

The Greek versions of both psychometric tests were considered reliable since these questionnaires have been validated in the Greek context [30,31]. The cutoff point used for the WISC III was <54, and the cutoff point used for the BDI II was >31 [31,32]. If the total score was less than these threshold values, the cognitive abilities and the depression symptoms were classified as ‘severely impaired’ or ‘severe,’ respectively.

We used the ICD-10 (International Classification of Diseases) of mental and behavioral disorders to obtain diagnosis for mental health disorders. It is to be noted that the ICD-10 requires revision due to the ongoing “scientific progress and experience.” However, the new edition of ICD-11 is expected to be released in January 2022. The ICD-10 has been in use since 1992.

Ethical considerations

The authors obtained adolescent consent and parental consent for adolescent participants. If adolescents and their parents were willing to participate, they were given adequate information about the design, purpose, nature, and confidentiality of the study. Moreover, they were informed that participation was voluntary, and that consent could be withdrawn at any time during the course of the study. Informed consent to participate was then obtained from each participant and his or her parent(s) prior to participating in this study and documented in recording at the time of the interviews. Anonymity and confidentiality were maintained throughout the study.

The participants’ anonymity was preserved. Their data were stored in a strictly confidential fashion. The study and consent procedure were approved by the ethics committee affiliated with Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Faculty of Health Sciences, Department of Medicine (No: 9302 12/7/17).

Statistical analysis method

The SPSS statistical package was used for the processing of data. Initially, the quantitative variables were examined for their normality and the existence of outliers. The normality of distribution was examined through the histogram and the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests for the variables of age, WISC and BDI. The boxplot was used to detect outliers. The Mann-Whitney test was applied with sex as an independent variable and age, WISC scores and BDI scores as dependent variables.

The binomial test was applied to check for a statistically significant deviation in the distribution regarding sex. To determine the correlations between the variables age, total WISC scores and total BDI scores, Spearman's rank correlation coefficient was used. To determine the frequency distribution of the BDI questions, the chi-square goodness-of-fit test was applied. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to assess whether the median scores per adolescence period subcategory demonstrated statistically significant differences.

Results

Both the histogram picture and the test results refer to a non-normal distribution for age (Kolmogorov-Smirnov: p<0.05. Shapiro-Wilk: p<0.01), WISC scores (Kolmogorov-Smirnov: p<0.01. Shapiro-Wilk: p<0.01) and BDI scores (Kolmogorov-Smirnov: p<0.05. Shapiro-Wilk: p<0.01). Boxplots revealed the existence of outliers for the WISC scores (case 21, score 41) and BDI scores (case 46, score 55). Although it is recommended in statistics to delete outliers, it was decided to maintain them in the present study due to their clinical value. Taking into consideration the above data about non-normal distribution and the existence of outliers, nonparametric tests were applied.

During the exploratory analysis, it was examined whether the answers of the participants differed based on sex. For this purpose, the Mann-Whitney test was applied with sex as an independent variable and age, WISC scores and BDI scores as dependent variables (Table 1).

|

|

M.S. |

S.D. |

Min.V. |

Max.V. |

n |

|

Age |

14.85 |

1.67 |

12,0 |

18,0 |

50 |

|

Boy |

14.97 |

1.67 |

13,0 |

17,5 |

22 |

|

Girl |

14.75 |

1.70 |

12,0 |

18,0 |

28 |

|

WISC |

94.93 |

14.39 |

41 |

133 |

45 |

|

Boy |

95.95 |

16.76 |

41 |

116 |

19 |

|

Girl |

94.19 |

12.69 |

77 |

133 |

26 |

|

BDI |

17.72 |

10.78 |

1 |

55 |

47 |

|

Boy |

14.95 |

8.19 |

3 |

34 |

20 |

|

Girl |

19.78 |

12.09 |

1 |

55 |

27 |

|

M.S.: Mean Scores; S.D.: Standard Deviation; Min.V.: Minimum Value; Μax.V.: Maximum Value |

|||||

The results showed that for all three variables, there were no statistically significant differences between boys and girls in their answers (age U=273.00, exact p=0.67; WISC U=183.50, exact p=0.15; BDI U=214.00, exact p=0.23).

Research of diagnosis

In total, 50 children and adolescents with a mean age of 15 years participated in the study. A total of 42.9% of participants were boys, and 57.1% were girls. The application of the binomial test demonstrated that the distributions were not significantly different (exact p=0.39). The mean WISC score of the participants was 95 points, and the mean BDI score was 17.7 (Table 1). In Table 2, we present in detail the mean scores and standard deviations of each BDI question. The highest mean scores were observed for the questions “Change of sleep” and “Difficulty in concentration,” while the lowest mean scores were observed for the questions “Loss of interest in sex” and “Suicidal ideas.”

|

Symptom |

M.S. |

S.D. |

N |

|

1. Sadness |

0.87 |

0.93 |

46 |

|

2. Pessimism |

1.13 |

1.05 |

46 |

|

3.Past failure |

0.70 |

0.96 |

46 |

|

4. Loss of pleasure |

0.91 |

0.94 |

46 |

|

5. Guilty feeilings |

0.78 |

0.89 |

46 |

|

6. Punishment feelings |

0.82 |

0.96 |

45 |

|

7. Self-dislike |

0.91 |

1.03 |

46 |

|

8. Self-criticalness |

1.02 |

0.93 |

46 |

|

9. Suicidal thoughts |

0.56 |

0.84 |

45 |

|

10. Crying |

0.78 |

1.05 |

46 |

|

11. Agitation |

0.74 |

0.80 |

46 |

|

12. Loss of interest |

0.74 |

0.91 |

46 |

|

13. Indecisiveness |

1.07 |

1.06 |

46 |

|

14. Worthlessness |

0.83 |

1.04 |

46 |

|

15. Loss of energy |

1.15 |

0.99 |

46 |

|

16. Changes in sleeping |

1.24 |

0.97 |

46 |

|

17. Irritability |

1.00 |

0.93 |

45 |

|

18. Changes in appetite |

0.91 |

0.99 |

46 |

|

19. Concentration difficulty |

1.22 |

0.99 |

46 |

|

20. Tiredness |

0.96 |

0.97 |

46 |

|

21. Loss of interest in sex |

0.42 |

0.92 |

38 |

Regarding the total BDI score, we considered a score of 17 as the differentiating point of depressive mood, taking into consideration the proposal of Giannakou et al. [32]. In the present research, 23 out of 47 BDI participants had a total score of 17 and above.

Distribution of diagnosis (diagnosis-related groups)

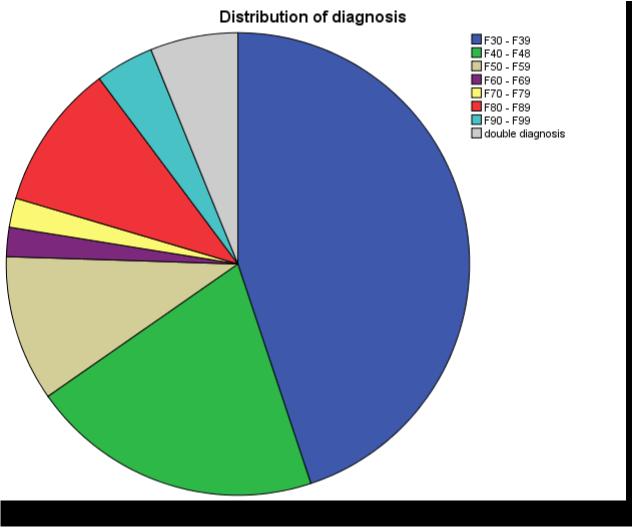

A total of 44.9% of participants were in the F30-F39 category [manic episode, bipolar affective disorder, depressive episode, recurrent depressive disorder, persistent mood disorders (cyclothymia, dysthymia), other mood disorders (ICD-10)] (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Distribution of diagnosis.

A total of 20.4% of participants were in the F40-F48 category (neurotic and somatoform disorders, such as phobic anxiety disorder, anxiety disorders, obsessive–compulsive disorder, adjustment disorders, dissociative disorders).

A total of 10.2% of participants were in the F50-F59 category (eating disorders, sleep disorders, sexual dysfunction, substance abuse. Importantly, this category includes anorexia nervosa).

A total of 2% of participants were in the F60-F69 and F70-F79 categories (personality disorders and intellectual disability, respectively).

A total of 10.2% of participants were in the F80-F89 category (developmental disorders of speech and language, disorders of scholastic skills, and pervasive developmental disorders).

A total of 4.1% of participants were in the F90-F99 category (hyperkinetic disorders, conduct disorders, emotional disorders with onset specific to childhood, tic disorders, disorders of social functioning with onset specific to childhood).

A total of 6.1% of participants were in the Dual Diagnosis category.

Sleep disorders were also commonly reported on the BDI (22.4%).

Frequency distribution of BDI questions

The chi-square goodness-of-fit test was used to investigate whether the participants chose a score with the same frequency in each BDI question or whether they differed (Table 3). As Table 2 portrays, the participants reported different answers except for the questions regarding “Reduction of energy, Change of sleep, Difficulty in concentration,” where answers were distributed with more uniformity. In general, participants tended to select the first two scores, which refer to a lack of symptoms or less severe symptoms. The selection of higher scores, referring to more severe symptoms, was observed for the question regarding “Pessimism, Reduction of energy, Difficulty in concentration.”

|

|

Score (%) |

|

|

|||

|

Symptom |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

χ2 (3) |

N |

|

Sadness |

19 (38.8) |

18 (36.7) |

5 (10.2) |

4 (8.2) |

17.13** |

46 |

|

Pessimism |

18 (36.7) |

8 (16.3) |

16 (32.7) |

4 (8.2) |

11.39** |

46 |

|

Feeling of failure |

28 (57.1) |

6 (12.2) |

10 (20.4) |

2 (4.1) |

34.35*** |

46 |

|

Decreased enjoyment |

19 (38.8) |

15 (30.6) |

9 (18.4) |

3 (6.1) |

12.78** |

46 |

|

Guilt |

21 (42.9) |

17 (34.7) |

5 (10.2) |

3 (6.1) |

20.44*** |

46 |

|

Punishment |

21 (42.9) |

15 (30.6) |

5 (10.2) |

4 (8.2) |

17.84*** |

45 |

|

Self-dislike |

20 (40.8) |

16 (32.7) |

4 (8.2) |

6 (12.2) |

15.57*** |

46 |

|

Self-criticism |

15 (30.6) |

19 (38.8) |

8 (16.3) |

4 (8.2) |

11.91** |

46 |

|

Suicidal ideas |

27 (55.1) |

14 (28.6) |

1 (2.0) |

3 (6.1) |

38.11*** |

45 |

|

Cry |

26 (53.1) |

9 (18.4) |

6 (12.2) |

5 (10.2) |

25.13*** |

46 |

|

Worry |

21 (42.9) |

17 (34.7) |

7 (14.3) |

1 (2.0) |

21.83*** |

46 |

|

Loss of interest |

24 (49.0) |

12 (24.5) |

8 (16.3) |

2 (4.1) |

22.52*** |

46 |

|

Indecision |

17 (34.7) |

16 (32.7) |

6 (12.2) |

7 (14.3) |

8.78* |

46 |

|

Unworthiness |

25 (51.0) |

8 (16.3) |

9 (18.4) |

4 (8.2) |

22.35*** |

46 |

|

Reduction of energy |

15 (30.6) |

13 (26.5) |

14 (28.6) |

4 (8.2) |

6.70 |

46 |

|

Changes of sleep |

11 (22.4) |

19 (38.8) |

10 (20.4) |

6 (12.2) |

7.74 |

46 |

|

Irritation |

15 (30.6) |

19 (38.8) |

7 (14.3) |

4 (8.2) |

12.87** |

45 |

|

Changes of appetite |

20 (40.8) |

14 (28.6) |

8 (16.3) |

4 (8.2) |

12.78** |

46 |

|

Difficulty in concentration |

14 (28.6) |

12 (24.5) |

16 (32.7) |

4 (8.2) |

7.22 |

46 |

|

Fatigue |

17 (34.7) |

19 (38.8) |

5 (10.2) |

5 (10.2) |

14.87** |

46 |

|

Loss of interest in sex |

30 (61.2) |

3 (6.1) |

2 (4.1) |

3 (6.1) |

59.05*** |

38 |

|

*p<0.05. **p<0.01. ***p<0.001 |

||||||

In the last question referring to loss of interest in sex, the percentage of participants who did not answer the question reached 22.4%, and it is the highest compared to the rest of the questions (38 people versus 45 or 46). Thirty adolescents (61.2%) selected the answer “I have not noticed any recent change in my interest in sex,” 3 adolescents (6.1%) were less interested in sex than they used to be, 2 adolescents (4.1%) had almost no interest in sex, and 3 adolescents (6.1%) had lost interest in sex completely.

The vast majority of answers sums to the first score selection referring to answer “I have not noticed any recent change in my interest in sex,” which corresponds to a score of 0. Many of the participants had no history of sexual intercourse.

Among the BDI questions, only on question 12 (loss of interest) there was a statistically significant difference (early: 18.36, middle: 22.83, late: 31,32, χ2(2) = 6.99, p<0.05).

Regarding sleep disorders in our sample, in the analytical form, the answers to BDI question 16 (Change of sleep) were distributed as follows (this could be a chart in the appendix and described briefly here in paragraph form):

|

I sleep as well as usual (0): |

11 (22.4%) |

|

I sleep a little more than usual (1a): |

9 (18.4%) |

|

I sleep a little less than usual (1b): |

10 (20.4%) |

|

I sleep much more than usual (2a): |

5 (10.2%) |

|

I sleep much less than usual (2b): |

5 (10.2%) |

|

I sleep most hours of the day (3a): |

1 (2.0%) |

|

I wake up 1-2 hours early and can’t go back to sleep (3b): |

5 (10.2%) |

Adolescence categories

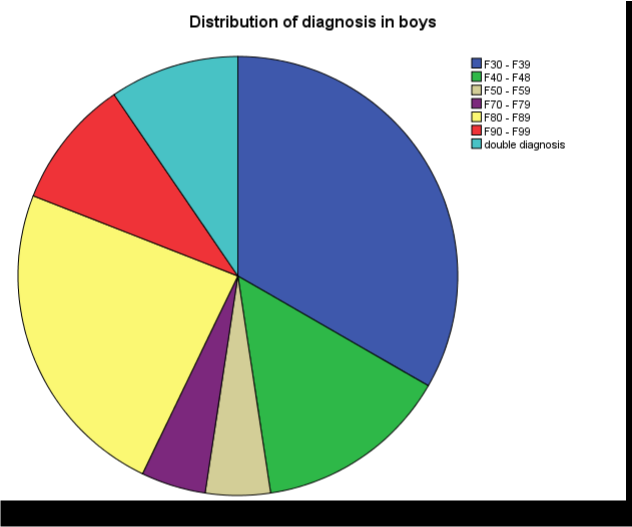

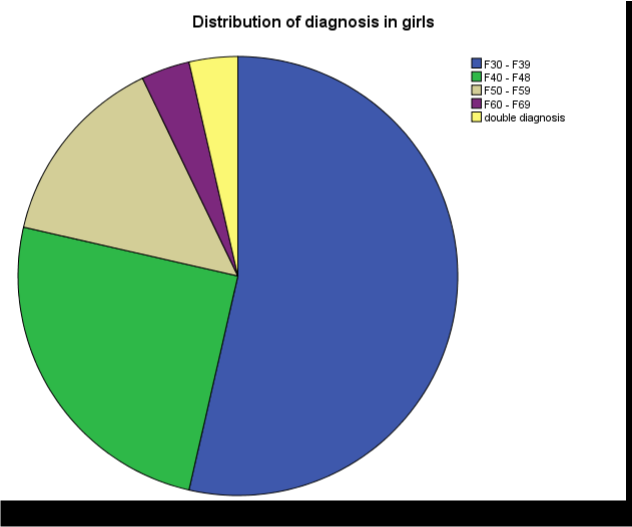

For the investigation of a potential correlation between the adolescence period and the intelligence level and the BDI score, participants were divided into three categories: early adolescence (10-13 years), middle adolescence (14-17 years) and late adolescence (17-21 years). Fourteen of the participants belonged to the first category, 24 belonged to the second category, and 12 belonged to the third category. See distribution of diagnosis in boys and girls in Figure 2 and 3, respectively.

Figure 2. Distribution of diagnosis in boys.

Afterwards, the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test was applied with adolescence stage as the independent variable and WISC and BDI scores as the dependent variables.

Figure 3. Distribution of diagnosis in girls.

WISC and BDI scores

The Kruskal-Wallis test showed that the median scores in each subcategory did not differ to a statistically significant degree in regard to the scoring of the participants in the WISC test (early: 20.68, middle: 21.89, late: 29.33, χ2(2)=2.70, p=0.26) and in the BDI (early: 23.92, middle: 23.46, late: 25.23, χ2(2)=0.13, p=0.94). Among the sub-questions of the BDI, a statistically significant difference was observed only in question 12 (loss of interest) (early: 18.36, middle: 22.83, late: 31.32, χ2(2)=6.99, p<0.05).

In conclusion, the participants did not differentiate as to their WISC and BDI scores in regard to the adolescence stage they were going through (early, middle, late). There is, however, the exception of the sub-question “Loss of interest,” where the highest scores were observed in late adolescence, while the lowest scores were observed in early adolescence.

Discussion

The sample of our study consisted of fifty adolescents with mental disorders who were undergoing psychotherapy. The most prevalent diagnosis (44.9%) was mood disorder (F30-F39). In this category, changes in mood were dominant and moved towards depression or towards euphoria. Changes in mood were usually accompanied by a change in the level of general activity. It can be hypothesized that in our sample, the changes in everyday life (sleep, concentration, pessimism) may have motivated individuals to seek assistance, as indicated by the high scores on the BDI. Recent evidence suggests an association between urbanization and mood disorders [33]. The high prevalence of mood disorders among adolescents may be partly explained by the urbanization model that has been developed in Greece over the last decades. Furthermore, over recent years, Greece has adopted extreme austerity measures that have led to changes in the social landscape and profoundly affected citizens’ mental health. For instance, literature states that “the economic crisis that hit Italy has posed threats to Italians' mental health and wellbeing” [34]. Other authors state: "Regarding financial distress, it was found to bear a statistically significant association with major depression but not with generalized anxiety disorder” [35]. The fact that mood disorders among adolescents were found in high prevalence may be partly explained by the recent Greek economic crisis, which may be an underlying driving factor. At any rate, it is crucial to bear in mind that “social and cultural factors may influence emergence of mental health problems” [36].

In the F30-F39 category, girls with mood disorders outnumbered boys with mood disorders by a significant amount. In international studies, it was found that between 1987 and 1999, adolescent girls presented an increase in psychological stress [37]. Females seem to be more likely to develop mood disorders. This has been confirmed by both our results in this study group and international studies [38,39]. A systematic review published in 2014 found that the majority of studies reported an increase in internalizing problems in adolescent girls [36].

A total of 20.4% of participants had an F40-F48 diagnosis (neurotic disorders). In this category, 14.3% of girls, compared to 6.1% of boys, develop these specific disorders in a higher percentage, specifically phobic disorders and panic disorders with a 2:1 to 3:1 ratio. For unspecified reasons, girls appear to be more vulnerable to the development of neurotic disorders. For instance, it is stated that (fixed the font)” the symptoms of neurotic disorders were more strongly expressed and more common in girls” [40].

The forms of unmanageable stress during adolescence are the same as those appearing in the other stages of life. Anxiety attacks usually start during adolescence and may be accompanied by difficulty in decision making or by somatization [41]. Overall, anxiety disorders and depressive disorders are strongly related [42-44].

A total of 10.2% (8.2% girls, 2% boys) of participants belonged to the F50-F59 category, which includes eating disorders, sleep disorders, sexual dysfunction, and substance use. Anorexia nervosa is a life-threatening disorder if not treated in time. Cultural factors (such as beauty models and “perfect” body image) can profoundly affect the anorectic psychopathology [45]. Anorexia nervosa is a relatively common eating disorder in adolescent females with the highest mortality rate of all mental disorders [46,47]. In the literature, the peak onset of the anorectic psychopathology during adolescence is associated with better prognosis [46,47]. A study during the period 2013-2014 reported that 31.6% of Australian adolescents experienced disordered eating [48]. A meta-analysis of 41 studies showed an increase in the prevalence of eating disorders (3.7% vs. 1.8%) [49]. Eating disorders are some of the most prevalent disorders in adolescence, and their prevalence continues to increase [50].

Sleep disorders were common in the study group according to the BDI (22.4%). Chronic sleep disorders are considered a common condition among adolescents. There has been awareness in recent years concerning the quality of sleep and mental health in the context of child and adolescent psychiatry. Prior research has shown that insomnia is more common in girls than in boys [41,51]. Our findings are consistent with previous studies. Sleep problems are related to sleep quantity and quality in adolescents, difficulties in falling sleep, day drowsiness, and sleep that is not restful [52]. Bad sleep quality may profoundly affect adolescents’ next day functioning, thus causing other serious problems. Perhaps that is why psychiatric assistance may often be provided not at the family’s request but at the adolescent’s request.

It has been estimated that in approximately 67% of adolescents with sleep concerns, there is co-occurrence of mental health problems in almost similar rates in preschool and school age groups [53]. Furthermore, it is argued that sleep problems may be associated with poor academic performance [54]. Interestingly, Zhang et al. found that “sleep disturbance had significant mediating effects on the relationship between intrafamily conflict and mental health problems in Chinese adolescents” [55].

Regarding sexuality, while the vast majority of the participants in our study were very interested in improving their social and communicative skills and acceptance by peers, they did not show any interest in sex and sexuality. Literature argues that “conscious sexual identities, motivations and desires” are present during early and middle adolescence [56]. Low and moderate levels of compulsive sexual behavior are considered part of the normal development of sexuality among adolescents [57]. However, adolescent sexuality is cleanly demarcated from adult sexuality [58]. While elements of sexuality and sexual interest are observable in children and adolescents, adolescent sexuality is at a period of developmental change. Sexuality in adolescence is not a perfect mirror of adult sexuality. Elements such as sexual desire, sexual arousal, sexual function, and sexual behaviors might be regarded as cleanly demarcated from adult sexuality [58]. “Adolescence is a crucial period for emerging sexual orientation and gender identity…” [59].

The sexuality-related findings of our survey should be interpreted considering those of a previous Greek study, which found that in the entire metropolitan area of Athens, around 20% of adolescents had already initiated sexual activity before the age of 16 years [60]. Note, however, that 10.2% of the participants in our study were adolescents with autism spectrum disorders where there are difficulties in approaching the opposite gender [61]. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that “due to the core symptoms of the disorder spectrum… some autism spectrum disorder individuals might develop quantitatively above-average or nonnormative sexual behaviors and interests” [62]. Moreover, the fact that 44.9% of the participants in our study were adolescents with mood disorders and a high prevalence of pessimism/negativity (36.7%), reduced activity (30.6%) and concentration deficit (28.6%) may partly provide some explanation for the lack of interest in sex and sexuality among the participants in our study.

Two percent (2% girls, 0% boys) of participants belonged to the F60-F69 category (personality disorders, gender identity disorders). These disorders and especially borderline personality disorders (F60.3) are characterized by extreme behavioral models with serious deviations from average in relating and interacting with others. In our study group, girls presented with personality disorders, specifically borderline personality disorder, where instability and fluidity in interpersonal relations are characteristic and accompanied by emotional instability, discomfort and compulsive suicide attempts. This may partly explain the low prevalence of adolescents with (borderline) personality disorder among members of a sample consisting of adolescents who were fully engaging in their ongoing psychotherapy.

The low percentage in diagnosing personality disorders (PD) in our group is consistent with previous international data as personality disorders are usually set as diagnoses in adult life because of the constantly evolving and changing personality in adolescence. Although dysfunctional behavioral models are acknowledged in adolescents, these are described as peculiar developmental patterns and not as disorders [37,63]. Feenstra and Hutsebaut state, “Clinicians seem hesitant about diagnosing personality disorders in adolescents” [64]. Moreover, we found a higher prevalence of personality disorders in girls. Relatedly, it is to be noted that regarding borderline personality disorders, there is still no clear difference between males and females. Schulte Holthausen and Habel state that in borderline PD “it is still inconclusive to what extent prevalence differences as well differences in symptoms occur between the sexes” [65].

Two percent of participants presented with mental retardation, F70-F79 (2% boys, 0% girls). Mental retardation (intellectual disability) is a condition of retarded development of intellect with incomplete development of both social skills and linguistic and motor skills. In literature mental retardation is presented as a breakdown of in four levels. It is distinguished as mild, moderate, severe and profound, depending on the gravity of difficulties [66]. This may partly explain the low prevalence of adolescents with (mild) mental retardation among members of a sample consisting of adolescents with mental disorders who were fully engaging in their psychotherapy. Relatedly, mental retardation is very often intertwined with emotional regulation disorders [67]. In our study, higher prevalence of mild mental retardation was found in boys. However, the majority of studies did not report inconsistent prevalence estimates of mental retardation – related psychiatric symptoms and disorders by age group or gender [66]. This inconsistency may be due to the small sample size of our study or the fact that we included only adolescents engaged in psychotherapy. At any rate, it is crucial to bear in mind that the reported gender difference in adolescent mental health remains poorly understood [68].

A total of 10.2% of adolescents (10.2% boys, 0% girls) belonged to the F80-F89 category. In our study group, adolescents with a developmental disorder were in a therapeutic relationship with a specialist in the outpatient clinic. They themselves feel their peculiarity and are usually open to the family’s urging towards psychotherapy to improve their social and communicative skills and acceptance by peers. The fact that in our study group all the adolescents presenting with developmental disorder were boys is in agreement with international epidemiological data, where pervasive developmental disorders are more often observed in boys, with the gender ratio for the spectrum consistently reported at around 5:1 (males: females) [69].

A total of 4.1% (0% girls, 4.1% boys) belonged to the F90-F99 category. Conduct disorder is usual in childhood and adolescence, and it is more common in boys than girls, with a ratio varying from 4:1 to 12:1; this was similar to the findings of the current study, since only boys were in therapy for conduct disorder [70,71].

Limitations and Strengths

In this study we provide a descriptive statistics analysis from a small non-representative sample. As the sample is not representative, the conclusions are not representative for Greek adolescents and cannot be considered generalizable to the Greek population. This is a major limitation of this study. Furthermore, note that prior studies have conducted large-scale surveys of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders using random and population representative samples of adolescents (i.e., school-based or non-school studies), while we focused on adolescents with mental disorders who were already engaged in ongoing treatment. For that reason, our study participant number was limited. Another limitation of our study is the fact that our cross-sectional study was carried out in only one child and adolescent mental health care setting. Note, however, that this setting is one of the few tertiary child and adolescent mental health care settings in northern Greece.

Conclusions

The largest proportion of adolescents (44.9%) were found to suffer from mood (affective) disorders, while 20.4% suffered from neurotic disorders. Pessimism (32.7%), reduction of energy (28.6%), and difficulty in concentration (32.7%) were common. A total of 22.4% of adolescents complained of sleep disorders. Surprisingly, limited interest in sex was noted, which was in contrast with international and Greek data, where interest and experimentation around sex seem to preoccupy a high percentage of adolescents (not in therapy). Furthermore, sleep disorders, either as a symptom of an underlying disease or as an independent clinical condition, seem to preoccupy adolescents in this study, and this may have been the motive for them to seek treatment. For the most part, the findings of this study were consistent with the findings of prior studies; however, previous studies did not exclusively include adolescents engaging in ongoing psychotherapy. As we identified some inconsistencies with prior studies related to interest in sex and sleep disorders, further research is recommended for the investigation of possible correlations between these findings and ongoing psychotherapy engagement rates. It might be interesting to investigate whether these findings strongly motivate adolescents with mental disorders to engage in psychotherapy.

Footnotes

- For the processing of data, there were changes made to question 16 referring to the categorization of answers, where subcategories a and b were added.

Availability of Data and Materials

The datasets used and analyzed for this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

BDI: Beck Depression Inventory; DMC: Decision Making Capacity; ICD: International Classification of Diseases; PD: Personality Disorders; SDs: Standard Deviation score; SDM: Shared Decision-Making; WISC: Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children

Declarations

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the staff of the Department of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, Hippokration General Hospital of Thessaloniki (Greece), for their valuable cooperation for the recruitment of participants. They would also like to thank the participants of the present study and their families for their generous contribution.

Funding

Not applicable. There are no sources of funding to be declared.

Authors’ contributions

ET and PV developed the study concept and design. ET and PV analyzed and interpreted the data. E.D. conducted statistical data analysis. PV drafted the manuscript, and all authors provided critical revisions for important intellectual content. The study was supervised by PV. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

We confirm that all methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. As participants were under 18, informed consent was obtained from a parent and/or legal guardian. In addition, informed consent was obtained from adolescent participants. Both parents/legal guardians and adolescents were told at the start of the study that they have the right to withdraw from research at any time and without giving any reason and without reprisal. Before participation, each participant and his or her parent(s) were given information on the study and informed that his or her participation was voluntary while placing great weigh on the importance of maintaining confidentiality. This study and consent procedure was approved and monitored by the Research Ethics Review Board of the School of Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece (Decision Number: 9.302/12-07-2017).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

2. Hartley CA, Somerville LH. The neuroscience of adolescent decision-making. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences. 2015 Oct 1;5:108-15.

3. World Health Organization. Adolescent mental health: mapping actions of nongovernmental organizations and other international development organizations. 2012.

4. Bremberg S. Mental health problems are rising more in Swedish adolescents than in other Nordic countries and the Netherlands. Acta Paediatrica. 2015 Oct;104(10):997-1004.

5. Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA, Ivanova MY. International epidemiology of child and adolescent psychopathology I: diagnoses, dimensions, and conceptual issues. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2012 Dec 1;51(12):1261-72.

6. Rescorla L, Ivanova MY, Achenbach TM, Begovac I, Chahed M, Drugli MB, et al. International epidemiology of child and adolescent psychopathology II: integration and applications of dimensional findings from 44 societies. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2012 Dec 1;51(12):1273-83.

7. Karow A, Bock T, Naber D, Löwe B, Schulte-Markwort M, Schäfer I, et al. Die psychische Gesundheit von Kindern, Jugendlichen und jungen Erwachsenen–Teil 2: Krankheitslast, Defizite des deutschen Versorgungssystems, Effektivität und Effizienz von „Early Intervention Services “. Fortschritte der Neurologie· Psychiatrie. 2013 Nov;81(11):628-38.

8. Polanczyk GV, Salum GA, Sugaya LS, Caye A, Rohde LA. Annual research review: A meta-analysis of the worldwide prevalence of mental disorders in children and adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2015 Mar;56(3):345-65.

9. Erskine HE, Baxter AJ, Patton G, Moffitt TE, Patel V, Whiteford HA, et al. The global coverage of prevalence data for mental disorders in children and adolescents. Epidemiology and psychiatric sciences. 2017 Aug;26(4):395-402.

10. Laufer M. (transl. Tsianti V.) Adolescent disturbance and breakdown, Athens: Kastaniotis. 1992, pp: 18 et seq. [in Greek].

11. Gmeinwieser S, Schneider KS, Bardo M, Brockmeyer T, Hagmayer Y. Risk for psychotherapy drop-out in survival analysis: The influence of general change mechanisms and symptom severity. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2020 Nov;67(6):712-22.

12. Bolton Oetzel K, Scherer DG. Therapeutic engagement with adolescents in psychotherapy. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 2003;40(3):215-25.

13. Warnick EM, Bearss K, Weersing VR, Scahill L, Woolston J. Shifting the treatment model: Impact on engagement in outpatient therapy. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2014 Jan;41:93-103.

14. Roos J, Werbart A. Therapist and relationship factors influencing dropout from individual psychotherapy: A literature review. Psychotherapy Research. 2013 Jul 1;23(4):394-418.

15. Sharf J, Primavera LH, Diener MJ. Dropout and therapeutic alliance: a meta-analysis of adult individual psychotherapy. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 2010 Dec;47(4):637-45.

16. Hayes D, Edbrooke-Childs J, Town R, Wolpert M, Midgley N. Barriers and facilitators to shared decision making in child and youth mental health: clinician perspectives using the Theoretical Domains Framework. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2019 May 1;28:655-66.

17. Hayes D, Fleming I, Wolpert M. Developing safe care in mental health for children and young people: drawing on UK experience for solutions to an under-recognised problem. Current Treatment Options in Pediatrics. 2015 Dec;1:309-19.

18. Dixon LB, Holoshitz Y, Nossel I. Treatment engagement of individuals experiencing mental illness: review and update. World Psychiatry. 2016 Feb;15(2):189.

19. Katz AL, Webb SA, Macauley RC, Mercurio MR, Moon MR, Okun AL, et al. Informed consent in decision-making in pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2016 Aug 1;138(2):e20161485.

20. Roberson AJ, Kjervik DK. Adolescents' perceptions of their consent to psychiatric mental health treatment. Nursing Research and Practice. 2012 Jan 1;2012: 379756.

21. Radoilska L, editor. Autonomy and mental disorder. Oxford University Press; 2012. pp. 328.

22. Widdershoven GA, Ruissen A, van Balkom AJ, Meynen G. Competence in chronic mental illness: the relevance of practical wisdom. Journal of Medical Ethics. 2017 Jun 1;43(6):374-8.

23. Friedman M. Autonomy, gender, politics. Oxford University Press; 2003.

24. Hermann H, Trachsel M, Elger BS, Biller-Andorno N. Emotion and value in the evaluation of medical decision-making capacity: a narrative review of arguments. Frontiers in Psychology. 2016 May 26;7:765.

25. Grootens-Wiegers P, Hein IM, van den Broek JM, de Vries MC. Medical decision-making in children and adolescents: developmental and neuroscientific aspects. BMC Pediatrics. 2017 Dec;17(1):120.

26. American Medical Association AMA code of medical ethics. 2016. Available at: https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/pediatric-decision-making. (last access: 2 December 2021).

27. Miller VA. Involving youth with a chronic illness in decision-making: highlighting the role of providers. Pediatrics. 2018 Nov;142(Supplement_3):S142-8.

28. Sibley A, Pollard AJ, Fitzpatrick R, Sheehan M. Developing a new justification for assent. BMC Medical Ethics. 2016 Dec;17:2.

29. Dow-Edwards D, MacMaster FP, Peterson BS, Niesink R, Andersen S, Braams BR. Experience during adolescence shapes brain development: From synapses and networks to normal and pathological behavior. Neurotoxicology and Teratology. 2019 Nov 1;76:106834.

30. Lange AM, van der Rijken RE, Delsing MJ, Busschbach JJ, van Horn JE, Scholte RH. Alliance and adherence in a systemic therapy. Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2017 Sep;22(3):148-54.

31. Georgas D, Paraskeuopoulos Ι, Mpezevegkis Η, Giannitsas ΝD. Greek WISC-III: Examiner Quide, Athens: Ellinika Grammata, 1997.

32. Giannakou M, Roussi P, Kosmides ME, Kiosseoglou G, Adamopoulou A, Garyfallos G. Adaptation of the Beck Depression Inventory-II to Greek population. Hellenic Journal of Psychology. 2013;10:120-46.

33. Hoare E, Jacka F, Berk M. The impact of urbanization on mood disorders: an update of recent evidence. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2019 May 1;32(3):198-203.

34. Odone A, Landriscina T, Amerio A, Costa G. The impact of the current economic crisis on mental health in Italy: evidence from two representative national surveys. The European Journal of Public Health. 2018 Jun 1;28(3):490-5.

35. Economou M, Peppou L, Fousketaki S, Theleritis C, Patelakis A, Alexiou T, et al. Economic crisis and mental health: Effects on the prevalence of common mental disorders. Psychiatriki. 2013 Oct-Dec;24(4):247-61.

36. Bor W, Dean AJ, Najman J, Hayatbakhsh R. Are child and adolescent mental health problems increasing in the 21st century? A systematic review. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2014 Jul;48(7):606-16.

37. West P, Sweeting H. Fifteen, female and stressed: changing patterns of psychological distress over time. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2003 Mar;44(3):399-411.

38. Kuehner C. Why is depression more common among women than among men?. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2017 Feb 1;4(2):146-58.

39. Slavich GM, Sacher J. Stress, sex hormones, inflammation, and major depressive disorder: Extending Social Signal Transduction Theory of Depression to account for sex differences in mood disorders. Psychopharmacology. 2019 Oct;236(10):3063-79.

40. Krauss H, Buraczynska-Andrzejewska B, Piatek J, Sosnowski P, Mikrut K, Glowacki M, et al. Occurrence of neurotic and anxiety disorders in rural schoolchildren and the role of physical exercise as a method to support their treatment. Annals of Agricultural and Environmental Medicine. 2012;19(3):351-6.

41. Ravens-Sieberer U, Otto C, Kriston L, Rothenberger A, Döpfner M, Herpertz-Dahlmann B, Barkmann C, et al. The longitudinal BELLA study: design, methods and first results on the course of mental health problems. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2015 Jun;24:651-63.

42. Seeley JR, Kosty DB, Farmer RF, Lewinsohn PM. The modeling of internalizing disorders on the basis of patterns of lifetime comorbidity: associations with psychosocial functioning and psychiatric disorders among first-degree relatives. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2011 May;120(2):308-21.

43. Tiller JW. Depression and anxiety. The Medical Journal of Australia. 2013 Oct 29;199(6):S28-31.

44. Choi KW, Kim YK, Jeon HJ. Comorbid anxiety and depression: clinical and conceptual consideration and transdiagnostic treatment. Anxiety Disorders: Rethinking and Understanding Recent Discoveries. 2020:219-35.

45. Kountza M, Garyfallos G, Ploumpidis D, Varsou E, Gkiouzepas I. La comorbidité psychiatrique de l’anorexie mentale: une étude comparative chez une population de patients anorexiques français et grecs. L'Encéphale. 2018 Nov 1;44(5):429-34.

46. Jagielska G, Kacperska I. Outcome, comorbidity and prognosis in anorexia nervosa. Psychiatr Pol. 2017 Apr 30;51(2):205-18.

47. Neale J, Hudson LD. Anorexia nervosa in adolescents. British Journal of Hospital Medicine. 2020 Jun 2;81(6):1-8.

48. Sparti C, Santomauro D, Cruwys T, Burgess P, Harris M. Disordered eating among Australian adolescents: Prevalence, functioning, and help received. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2019 Mar;52(3):246-54.

49. Flament MF, Buchholz A, Henderson K, Obeid N, Maras D, Schubert N, et al. Comparative distribution and validity of DSM‐IV and DSM‐5 diagnoses of eating disorders in adolescents from the community. European Eating Disorders Review. 2015 Mar;23(2):100-10.

50. Herpertz-Dahlmann B. Adolescent eating disorders: update on definitions, symptomatology, epidemiology, and comorbidity. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics. 2015 Jan 1;24(1):177-96.

51. Braconnier A., Marcelli D. [The thousand faces of adolescence]. Athens: Kastaniotis; 2002. pp: 30 et seq.

52. Kansagra S. Sleep disorders in adolescents. Pediatrics. 2020 May;145(Supplement_2):S204-9.

53. Van Dyk TR, Becker SP, Byars KC. Rates of mental health symptoms and associations with self-reported sleep quality and sleep hygiene in adolescents presenting for insomnia treatment. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 2019 Oct 15;15(10):1433-42.

54. Hysing M, Harvey AG, Linton SJ, Askeland KG, Sivertsen B. Sleep and academic performance in later adolescence: Results from a large population-based study. Journal of Sleep Research. 2016 Jun;25(3):318-24.

55. Zhang L, Yang Y, Liu ZZ, Jia CX, Liu X. Sleep disturbance mediates the association between intrafamily conflict and mental health problems in Chinese adolescents. Sleep Medicine. 2018 Jun 1;46:74-80.

56. Reynolds MA, Herbenick DL. Using computer-assisted self-interview (CASI) for recall of childhood sexual experiences. Sexual Development in Childhood. 2003 Nov 1:77-81.

57. Efrati Y, Dannon P. Normative and clinical self-perceptions of sexuality and their links to psychopathology among adolescents. Psychopathology. 2018;51(6):380-9.

58. Fortenberry JD. Puberty and adolescent sexuality. Hormones and behavior. 2013 Jul 1;64(2):280-7.

59. McClain Z, Peebles R. Body image and eating disorders among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth. Pediatric Clinics. 2016 Dec 1;63(6):1079-90.

60. Tsitsika A, Andrie E, Deligeoroglou E, Tzavara C, Sakou I, Greydanus D, et al. Experiencing sexuality in youth living in Greece: contraceptive practices, risk taking, and psychosocial status. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology. 2014 Aug 1;27(4):232-9.

61. Fernandes LC, Gillberg CI, Cederlund M, Hagberg B, Gillberg C, Billstedt E. Aspects of sexuality in adolescents and adults diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders in childhood. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2016 Sep;46:3155-65.

62. Schöttle D, Briken P, Tüscher O, Turner D. Sexuality in autism: hypersexual and paraphilic behavior in women and men with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 2017 Dec;19(4):381-393.

63. Papageorgiou BA. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Thessaloniki: University Studio Press; 2005. pp: 128, 242 et seq.

64. Feenstra DJ, Hutsebaut J. De prevalentie, ziektelast, structuur en behandeling van persoonlijkheidsstoornissen bij adolescenten [The prevalence, burden, structure and treatment of personality disorders in adolescents]. Tijdschr Psychiatr. 2014;56(5):319-25.

65. Schulte Holthausen B, Habel U. Sex differences in personality disorders. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2018 Dec;20(12):107.

66. Buckley N, Glasson EJ, Chen W, Epstein A, Leonard H, Skoss R, et al. Prevalence estimates of mental health problems in children and adolescents with intellectual disability: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2020 Oct;54(10):970-84.

67. des Portes V. Intellectual disability. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. 2020;174:113-126.

68. Campbell OL, Bann D, Patalay P. The gender gap in adolescent mental health: a cross-national investigation of 566,829 adolescents across 73 countries. SSM-population Health. 2021 Mar 1;13:100742.

69. de Giambattista C, Ventura P, Trerotoli P, Margari F, Margari L. Sex differences in autism spectrum disorder: focus on high functioning children and adolescents. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2021 Jul 9;12:539835.

70. Szentiványi D, Halász J, Horváth LO, Kocsis P, Miklósi M, Vida P, et al. Quality of life of adolescents with conduct disorder: Gender differences and comorbidity with oppositional defiant disorder. Psychiatria Hungarica: A Magyar Pszichiatriai Tarsasag tudomanyos folyoirata. 2019 Jan 1;34(3):280-6.

71. Mohan L, Yilanli M, Ray S. Conduct Disorder. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. 2021.